ABSTRACT

There is growing attention to the ways in which climate change may affect sexual health, yet key knowledge gaps remain across global contexts and climate issues. In response, we conducted a scoping review to examine the literature on associations between climate change and sexual health. We searched five databases (May 2021, September 2022). We reviewed 3,183 non-duplicate records for inclusion; n = 83 articles met inclusion criteria. Of these articles, n = 30 focused on HIV and other STIs, n = 52 focused on sexual and gender-based violence (GBV), and n = 1 focused on comprehensive sexuality education. Thematic analysis revealed that hurricanes, drought, temperature variation, flooding, and storms may influence HIV outcomes among people with HIV by constraining access to antiretroviral treatment and worsening mental health. Climate change was associated with HIV/STI testing barriers and worsened economic conditions that elevated HIV exposure (e.g. transactional sex). Findings varied regarding associations between GBV with storms and drought, yet most studies examining flooding, extreme temperatures, and bushfires reported positive associations with GBV. Future climate change research can examine understudied sexual health domains and a range of climate-related issues (e.g. heat waves, deforestation) for their relevance to sexual health. Climate-resilient sexual health approaches can integrate extreme weather events into programming.

Background

Climate change has far-reaching environmental effects including alterations in climate patterns and increased extreme weather events such as storms, heatwaves, drought, fire, and heavy precipitation (Romanello et al., Citation2021). These extreme weather events harm human health and livelihoods through straining global food and water supplies (Phalkey et al., Citation2015; Stanke et al., Citation2013; Watts et al., Citation2019), in turn increasing food insecurity (Austin et al., Citation2021; Lobell et al., Citation2008; Zhao & Running, Citation2010) and migration (Dzomba et al., Citation2018; McMichael et al., Citation2012; Watts et al., Citation2019; Weine & Kashuba, Citation2012). In fact, climate change and related extreme weather events contribute to an array of direct and indirect health effects (Romanello et al., Citation2021; Watts et al., Citation2015), including malnutrition, infectious diseases, and mental health challenges (Lieber et al., Citation2021; Romanello et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2018; Whitmee et al., Citation2015; Women Deliver, Citation2021). Extreme weather events can also disrupt provision of, and access to, health services (Stanke et al., Citation2013). There is growing attention to how climate change and related extreme weather events may affect sexual health (Orievulu et al., Citation2022; Thurston et al., Citation2021; van Daalen et al., Citation2021).

Sexual health is a multifaceted concept, comprising comprehensive sexuality education and information; gender-based violence (GBV) prevention, support, and care; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted infections (STI) prevention and control; and sexual function and psychosexual counselling (Stephenson et al., Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2017). Yet most climate change-related literature to date has focused on one or two of these sexual health dimensions – GBV and HIV/STI (Orievulu et al., Citation2022; Thurston et al., Citation2021; van Daalen et al., Citation2021). For instance, a systematic review found that GBV perpetrated by strangers and close relationships increased during and following extreme weather events, and this increase was attributed to a range of factors including exacerbated economic insecurity, food insecurity, mental health stressors, disruptions to health and legal infrastructure, and increased gender inequity (Van Daalen et al., Citation2022). The authors underscore that ‘extreme events do not cause GBV; rather, extreme events exacerbate drivers of violence or create enabling environments for this behaviour. The primary causes are systematic social and patriarchal structures enabling and normalising GBV’ (p. e519) (Van Daalen et al., Citation2022). In another systematic review, authors highlight complex linkages between drought and HIV treatment adherence in Africa, whereby economic and livelihoods related challenges were among the strongest determinants of antiretroviral therapy (ART) non-adherence (Orievulu et al., Citation2022). For instance, food and water insecurity may increase concerns about ART side effects, and drought can also result in human migration to seek employment or forage and water for livestock. In turn this migration can disrupt both connections to health systems and social support networks (Orievulu et al., Citation2022). These important reviews signal the need to better understand climate change, and a range of extreme weather events, and how they may affect multiple dimensions of sexual health.

There are three frameworks that are particularly relevant for conceptualising potential associations between climate change and sexual health. First, Women Deliver developed a framework examining linkages between climate change and GBV (Women Deliver, Citation2021). This framework posits that climate-related disasters and extreme weather events may increase mobility and migration that in turn elevate risks of trafficking and violence, and extreme weather events may also increase financial and other household stressors that can exacerbate existing violence and increase risks of child, early and forced marriage as a financial coping mechanism (Women Deliver, Citation2021). Second, Lieber et al.’s model of the linkages between climate change and HIV conceptualises that global changes in the environment, including temperature levels, natural disasters, floods and heat waves, may result in increased HIV acquisition risks and HIV morbidity and mortality through four pathways: migration, infectious disease, infrastructure erosion, and food insecurity (Lieber et al., Citation2021). For instance, changes in climate may alter the prevalence of vector-borne diseases such as malaria and leishmaniasis, and HIV co-infection with either malaria or leishmaniasis may worsen HIV outcomes (Lieber et al., Citation2021). Third, the ecosyndemics framework describes the interaction and synergistic associations between social (e.g. violence), health (e.g. mental health), and environmental (e.g. unstable environmental conditions) challenges (Tallman et al., Citation2022). For instance, migration, sex work, substance use, stress and violence are some of the mechanistic pathways connecting environmental disruption (e.g. construction of dams/highways in tropical forests) with increased STI acquisition risks (Tallman et al., Citation2022). Taken together, these conceptual frameworks offer a range of potential pathways to examine regarding the connections between climate change-related factors and sexual health outcomes that span social-ecological levels, including structural (e.g. livelihoods disruption), community (e.g. violence), interpersonal (e.g. transactional sex), and intrapersonal (e.g. stress).

Three key knowledge gaps remain regarding pathways from climate change-related factors, such as extreme weather events, and sexual health. First, most climate change and GBV reviews focus on displacement and disaster, and potential associations between other aspects of climate change (e.g. extreme heat, bushfires) and GBV are not well characterised. Specifically, identifying GBV risks that span multiple types of climate change-related issues and extreme weather events globally for all genders could inform climate-tailored GBV reduction approaches (IPCC, Citation2022). Second, there are knowledge gaps regarding a range of climate change-related effects and extreme weather events on HIV/STI prevention and care outcomes across global regions. A systematic review on drought and ART adherence among people living with HIV in Africa provided valuable regional insights (Orievulu et al., Citation2022), and could be complemented with a global review examining extreme weather events at large and both HIV prevention (Moorhouse et al., Citation2019) and care (Mugglin et al., Citation2021) cascades. Third, there is a dearth of literature exploring climate change and the other two pillars of sexual health, namely comprehensive sexuality education and sexual function and psychosexual counselling (Stephenson et al., Citation2017).

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a scoping review guided by the following research question: what is known in the literature about the associations and relationships between climate change and sexual health?

Methods

This scoping review explores the linkages between climate change and sexual health, with a focus on four dimensions of sexual health: comprehensive sexuality education; GBV; preventing and controlling HIV and STIs; and psychosexual counselling. Full methods for this review are outlined in the published study protocol (Logie et al., Citation2021) and summarised below.

Search strategy

Five databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science) were searched for relevant articles in May 2021 and updated in September 2022 using a search strategy informed by the WHO’s definition of sexual health (Stephenson et al., Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2017), and previous work on climate change-related extreme weather events (Bell et al., Citation2018). Search terms included those related to sexual health, GBV, and climate change/EWE/natural disasters. Searches were not limited by language, date, or geographic location and all records were managed in EndNote, Covidence, and Excel. Reference lists from included studies and review articles looking at related topics were also hand searched for additional articles the database searches might have missed.

Study selection and analysis

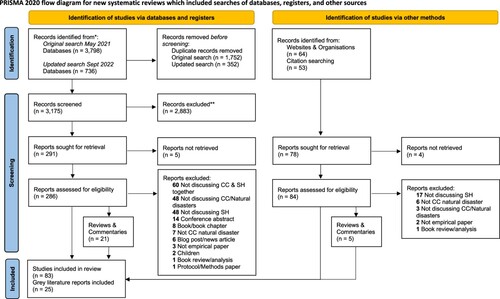

After duplicates were removed, titles and abstracts of all identified reviewed for eligibility by two reviewers. Articles had to discuss at least one of the four dimensions noted above of sexual health (i.e. sex education, sexual health counselling, STIs/HIV, GBV) in the context of climate change or EWE. Articles focusing on infants or children or exploring sexual health separately from climate change or extreme weather events were excluded. We considered quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies in this review. Differences were resolved through discussion; if consensus could not be reached, the article was moved to the full-text screen for further review. Full texts of articles passing the title/abstract screen were then reviewed by two reviewers based on the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, conference abstracts, protocols, books, and studies conducted in animals were excluded. All differences in screening at the full-text stage were reviewed by a third reviewer and/or discussed with all reviewers. Data was extracted from all articles included in the review by one reviewer and peer reviewed by a second.

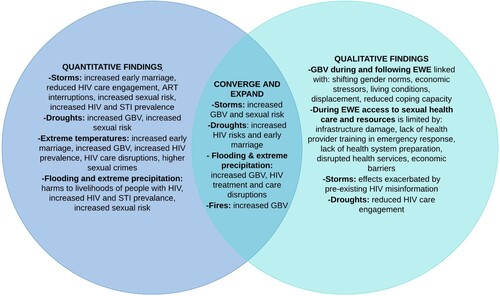

We used thematic analysis to narratively synthesise the articles and determine common themes. We grouped findings by type of climate change/EWE discussed and then stratified them into the four sexual health domains (comprehensive sexuality education; GBV; HIV and STI; psychosexual counselling). We aggregated and organised findings tabularly to explore overall common linkages between a climate-related factor and sexual health related outcomes, noting geographic regions and socio-demographic characteristics when provided (e.g. age, gender, sexual orientation, HIV serostatus etc.). We share these findings in narrative and tabular formats below. We then developed a summative joint display to illustrate the converge and divergence of areas of investigation and findings by qualitative and quantitative methods (McCrudden et al., Citation2021) to increase knowledge of the state of the research field on climate change and sexual health and inform recommendations for future research.

Results

Study characteristics

The combined searches (May 2021 and September 2022) returned 4,534 citations across the five databases. After removal of duplicates, 3,183 records were assessed for inclusion, with reference lists of all included articles and relevant commentaries or reviews hand searched for additional articles. A total of 83 articles met inclusion criteria and were included in this review, 52 focusing on GBV, 30 on HIV/STIs, and one on comprehensive sexuality education (; ). reports general characteristics of included studies.

Table 1. Summary of included article (n = 83) characteristics in scoping review on climate change-related factors and sexual health.

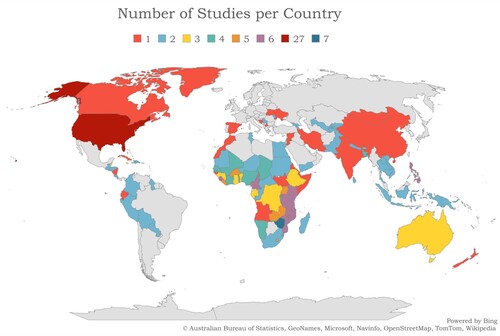

Included studies were published between 1997 and 2022 (50% published in 2018 or later), presenting data from 108 countries across all continents except Antarctica (). The countries are reflected in , and a full list of the number of studies included from each country is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 2. Map of countries of included studies in this scoping review. Included countries are represented with colours reflecting the number of studies from each country reported in the figure legend.

Sexual health issues

Among the 30 studies focusing on HIV/STIs, 25 focused only on HIV, four studies examined both HIV and STIs, and one focused on gonorrhea. Most studies assessed HIV prevention (n = 6) and care (n = 9) cascades. Articles also explored psychological (n = 3) (distress, depression, optimism) and socioeconomic (food, income insecurity) (n = 2) aspects of HIV. One article addressed HIV/STI transmission and prevention knowledge. Lastly, three articles examined prevalence (n = 2), and outreach, education, and support (n = 1) for STIs other than HIV. HIV/STI articles were predominantly quantitative (n = 20), with a minority using qualitative (n = 5) or mixed/multi (n = 5) methods. We provide an overview of sub-regional study characteristics of included articles in .

Table 2. Sub-regional study characteristics of articles (n = 83) included in scoping review on climate change-related factors and sexual health.

Most of the 52 articles examining GBV focused on violence between partners (n = 19) (including domestic violence, intimate partner violence (IPV), and dating violence), sexual violence (n = 19), or explored broad constructs of GBV or violence against women (VAW; n = 17), with several discussing multiple themes. Half of included articles (n = 26) were quantitative, 33% (n = 17) were qualitative, and 17% (n = 9) used mixed or multiple methods.

Articles are discussed below, categorised by type of extreme weather event. Several articles dealt with multiple disasters (e.g. flooding and drought) (Díaz & Saldarriaga, Citation2023; Masson et al., Citation2019), extreme temperatures and precipitation (Li et al., Citation2010; Samano et al., Citation2021), flooding and hurricanes (Enarson, Citation1999), and droughts and cyclones (Rai et al., Citation2021), and are represented in multiple sections. provides an overview of study site, methodology, and outcomes.

Table 3. Overview of articles (n = 83) included in scoping review on climate change-related factors and sexual health.

Hurricanes, cyclones, typhoons, and tropical storms

Almost half of included studies (n = 40) focused on storms including hurricanes (n = 31), typhoons (n = 3), cyclones (n = 5), and tropical storms (n = 1). Over half of the storm-focused studies were quantitative (n = 22), just over a quarter were qualitative (n = 10) and the remainder were mixed/multi method (n = 8). Studies focusing on hurricanes predominantly originated from the United States of America (USA, n = 26) and investigated HIV/STIs (n = 17) and GBV (n = 14). Hurricane Katrina (n = 15) was the most frequently investigated individual storm. Among studies discussing other types of storms, four explored typhoons and tropical storms in the Philippines and the remainder explored cyclones in Bangladesh, Fiji and Tonga (Beek et al., Citation2021), and India (Rai et al., Citation2021). All studies exploring non-hurricane storms (i.e. cyclones, typhoons) focused on GBV.

HIV and hurricanes

Of the 40 studies focussed on storms, nearly half (n = 18) investigated HIV/STIs and hurricanes. Most studies were quantitative (n = 10), and the remainder were qualitative (n = 4) and mixed/multi method (n = 4). Among the literature found, no other storm types were investigated alongside HIV/STIs. Studies identified disruptions in HIV prevention and care outcomes and mental health following hurricanes. These disruptions may be attributed to staffing difficulties affecting HIV treatment provision, displacement to shelters far from HIV clinics, and challenges accessing treatment and testing due to power outages and structural damage. For instance, authors reported decreases in HIV clinic attendance following hurricanes, with one quantitative study noting poorer HIV clinical outcomes in the 18 months following Hurricane Katrina (Robinson et al., Citation2011). Additionally, African Americans, men, and older individuals were most likely to have lower CD4 counts after the hurricane, suggesting that impacts of treatment disruptions were not experienced equally across race, gender, and age. The duration of care disruption varied, ranging from two to 17 weeks across two studies (Ekperi et al., Citation2018; Padilla et al., Citation2022). Some studies suggested testing rates for HIV (Geyer et al., Citation2018) and STIs (Nsuami et al., Citation2009) increased following hurricanes.

Three quantitative studies examined the intersections of hurricanes, HIV, and mental health (Cruess et al., Citation2000; Kilbourn, Citation1997; Reilly et al., Citation2009). One reported that people living with HIV with post-traumatic stress disorder were more likely than those without to have detectable viral loads, lower CD4 counts, and HIV treatment interruptions after Hurricane Katrina (Reilly et al., Citation2009). Another study, using self-reported data, found that gay men reported higher stress levels associated with living with HIV than from Hurricane Andrew and noted the importance of adaptive coping mechanisms for adapting to major stressors (Kilbourn, Citation1997). For instance, higher optimism levels among gay men living with HIV following Hurricane Andrew were significantly associated with lower hurricane-related distress and depression (Cruess et al., Citation2000).

Other hurricane-related studies documented practices that elevate HIV exposure and HIV prevalence. Among people who inject drugs, a mixed-methods study found that participants shared needles (28%) and preparation equipment (36%) with people they normally would not have during Hurricane Sandy, which was attributed to the hurricane-related closure of the needle exchange facility (Pouget et al., Citation2015). A spatial correlation study in the USA examined HIV infection rates in relation to hurricane events between 1851 and 2017, finding higher HIV infection rates in states with ≥5 (421 per 100,000) and ≥20 (453 per 100,000) hurricanes compared to the national average (365 per 100,000) (Sharpe, Citation2019). No explanation was offered for this observed geographical overlap between hurricanes and HIV infection.

One qualitative study addressed HIV/STI knowledge among forcibly displaced youth in Belize following Hurricane Mitch, reflecting a dimension of comprehensive sexuality education. Among the youth, HIV transmission and prevention misconceptions were reported, with just 45.5% believing needle-sharing was a means of HIV transmission and only 50% believing condoms could be used for HIV prevention (Westhoff et al., Citation2008). The authors stressed the importance of prioritising HIV/STI education, particularly after the immediate emergency phase, as refugee and IDP (internally displaced persons) settings often carry an increased risk of violence and potential exposure to HIV (Westhoff et al., Citation2008)

GBV and storms

The largest proportion of the 52 studies reporting on GBV focused on the impact of storms (n = 22). Most explored impacts on GBV broadly (n = 12), on IPV/DV (n = 8), and/or on sexual violence (n = 9), with overlap between the three groups. Notably, the one included study that investigated transactional sex and GBV focused on the impact of storms (Luetke et al., Citation2020). Most of the studies were quantitative (n = 12), with the remaining being qualitative (n = 6) and mixed/multi method (n = 4). The most common storm type examined was hurricanes (n = 14), predominantly Hurricane Katrina (n = 7).

Two quantitative studies conducted with student populations in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina found no statistically significant increase in sexual violence following the disaster (Fagen et al., Citation2011; Madkour et al., Citation2011). Authors suggest social cohesion, the physical buffer between the university campus and downtown New Orleans (Fagen et al., Citation2011), and increased mental health services in secondary schools post-Katrina (Madkour et al., Citation2011), might account for this non-significant change in sexual violence. Four additional quantitative studies, examining the general population rather than student populations, revealed statistically significant increases in the prevalence and/or risk of IPV following Hurricane Katrina (Anastario et al., Citation2009; Harville et al., Citation2011; Picardo et al., Citation2010; Schumacher et al., Citation2010). Finally, a quantitative study of high school students after Hurricane Ike found boys who did not evacuate during the storm had significantly higher odds of both perpetrating and experiencing sexual violence (Temple et al., Citation2011).

Several studies noted that storms increased community and/or household stress or exacerbated existing tensions, and this contributed to increased violence both generally (Bermudez et al., Citation2019; Nguyen, Citation2019), and specifically related to stressors of food insecurity (Bermudez et al., Citation2019; Luetke et al., Citation2020), poverty or financial insecurity (Bermudez et al., Citation2019; Luetke et al., Citation2020; Tanyag, Citation2018; True, Citation2013), and disruption of law and social order (Nguyen, Citation2019). GBV and poverty are interlinked, heightening women’s vulnerability to GBV before, during, and after disasters (Rezwana & Pain, Citation2021). Increased violence among displaced persons was attributed to lack of privacy and security in displacement camps (Ahmed et al., Citation2019; Alburo-Cañete, Citation2014; Tanyag, Citation2018). Finally, storms, GBV, physical health, and mental health concerns were interconnected. In one quantitative study, IPV and storm exposure significantly increased the risk of depression and PTSD (Schumacher et al., Citation2010), while another reported that sleeping problems, appetite dysregulation, low self-esteem, suicidal ideation, and depressive symptoms were associated with significantly increased odds of experiencing GBV after the storm (Anastario et al., Citation2008).

Drought

Drought was the focus of 15 included studies, most focused on low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC): multiple Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries together (n = 4), World Bank’s less developed countries (LDC), Zimbabwe (n = 2), and India (n = 2). Most studies were quantitative (n = 9), four were qualitative, and 2 were mixed/multi method. Seven drought-focused studies examined HIV and eight assessed GBV.

HIV and drought

Of the 15 studies in which drought was examined, four quantitative studies assessed associations between drought and HIV prevalence (Austin et al., Citation2021; Berndt & Austin, Citation2021; Burke et al., Citation2015; Low et al., Citation2019), finding a positive association between the two. Three of those studies (Austin et al., Citation2021; Berndt & Austin, Citation2021; Low et al., Citation2019) also reported a gendered relationship between drought and HIV, with drought positively associated with HIV prevalence in women and not men. Three studies, two in rural Zimbabwe (Gwatirisa & Manderson, Citation2012; Mazzeo, Citation2008) and one in South Africa (Orievulu & Iwuji, Citation2021), explored experiences of drought among people living with HIV. The authors indicated drought-related food and income insecurity might be exacerbated among people living with HIV, for example when agricultural labourers living with HIV are not healthy enough to work or if households prioritise paying for HIV-related healthcare over buying food (Gwatirisa & Manderson, Citation2012; Mazzeo, Citation2008). In these situations, food and/or income insecurity could extend beyond people living with HIV to their households.

One quantitative study reported an association between drought and higher HIV prevalence among adolescent girls aged 15–19 living in rural Lesotho (Low et al., Citation2019). The same study also found that living in a rural drought area was associated with lower educational attainment and an increase in high-risk sexual practices among adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 (Low et al., Citation2019). Authors suggest that drought elevated HIV acquisition risks via reduced educational access and changes in sexual practices, and drought-related migration was also linked with HIV risk among men and women (Low et al., Citation2019). The effect was modified by sex and age for HIV testing, whereby the negative association was highest for men and adolescents.

GBV and drought

Eight studies, including five quantitative, two qualitative, and one mixed/multi method, explored the relationship between drought and GBV, including IPV (n = 4), violence against women (VAW) (n = 2), and child marriage (n = 3), predominantly in SSA (n = 5).

Four quantitative studies investigated associations between IPV and drought and had differing findings: two reported significantly higher IPV among women experiencing drought (Peru (Díaz & Saldarriaga, Citation2023) and SSA (Epstein et al., Citation2020)) whereas the other two reported no significant associations (India (Rai et al., Citation2021) and SSA (Cools et al., Citation2020)). However, Rai and colleagues found a non-significant positive association between drought and physical IPV that was not further elaborated on (Rai et al., Citation2021). Findings on child marriage were similarly conflicting, most notably in comparison of early marriage in SSA and India (Corno et al., Citation2020). The authors of this quantitative study reported opposite associations in the two regions, with drought significantly associated with increased risk of early marriage in SSA and significantly associated with reduced risk of early marriage in India, despite drought having similar negative effects on crop yields. The other two studies investigating early marriage were qualitative and discussed how the economic harms brought about by drought increased risks of child and early marriage as a financial stress coping strategy (Esho et al., Citation2021; Hossen et al., Citation2021).

One quantitative study discussed potential mechanisms linking drought and IPV, suggesting the loss of crops or food supply may cause or exacerbate existing poverty and food insecurity which are both recognised IPV risk factors (Epstein et al., Citation2020). Lastly, the sole mixed/multi method study reported that violence may constrain women’s resilience following a natural disaster, potentially exacerbating power inequalities and preventing women from proactively managing emergent challenges (Masson et al., Citation2019).

Flooding

Almost 20% of studies (n = 15) focused on the impacts of flooding on sexual health, predominantly in LMIC, most commonly Bangladesh (n = 3) and India (n = 2); three additional studies originated in the USA and/or Canada. Six of the flooding-focused studies were qualitative, five were mixed/multi method, and four were quantitative. Most studies explored the impact on GBV (n = 13), largely focusing on IPV and/or sexual harassment. Two studies examined the impacts of flooding on people living with HIV, one in Thailand (Khawcharoenporn et al., Citation2013) and one in Namibia (Anthonj et al., Citation2015).

HIV and floods

Only two studies focused on flooding examined HIV as an outcome. In a quantitative study in Thailand, 3% (n = 7) of 217 people living with HIV self-reported missing their ART appointments due to flood-related HIV clinic closures (Khawcharoenporn et al., Citation2013). A qualitative study in a rural, flood-prone region of Namibia found that flooding led to a loss of work and income, poor household hygiene and sanitation, and an inability to access HIV services due to infrastructural damage to health facilities (Anthonj et al., Citation2015). These two studies highlight the interlinked effects of floods on healthcare and household infrastructure alongside livelihoods disruption that hold the potential to constrain HIV care access.

GBV and floods

Most studies examining floods focused on GBV (n = 13), n = 5 were qualitative, n = 5 mixed/multi method (n = 5), and n = 3 three quantitative. Eight studies across six countries reported increases in violence post-disaster. Displacement (Bradley et al. Citation2023; Madhuri, Citation2016), the influx of ‘strange men’ in their communities in Dhaka and Mumbai (Rashid & Michaud, Citation2000; Singh et al., Citation2018), and mental health challenges were noted as potential factors contributing to increased GBV following floods. Articles largely did not delineate mechanisms connecting GBV and floods, though one specifically noted disaster-related mental health problems could contribute to increased violence (Sohrabizadeh, Citation2016). A quantitative study reported that post-hurricane flooding was not significantly associated with IPV rates; noting that experiences of IPV pre-flooding were significantly associated with post-flooding IPV (Frasier et al., Citation2004). In another qualitative example from the United States, an IPV survivor reported that surviving the flood without her abusive partner allowed her to recognise she was ‘strong and competent enough to survive without him’ (Fothergill, Citation1999).

Extreme precipitation

Three quantitative studies included in this review examined the associations between extreme precipitation and HIV/STI prevalence, acquisition risks, and care outcomes (Li et al., Citation2010; Nagata et al., Citation2022; Samano et al., Citation2021). A study in Xiamen, China found higher prevalence of HIV and syphilis during periods of high precipitation, though no causal pathway was suggested (Li et al., Citation2010). Similarly, a cross-sectional population-based study from 21 countries in SSA found that heavy rainfall (≥1.5 deviation from the average precipitation index) was associated with 14% greater odds of HIV infection, 11% greater odds of STIs, and 12% greater odds of reporting a higher number of sexual partners (Nagata et al., Citation2022). Lastly, an ecological study in Miami, USA reported that HIV clinic attendance was 13% lower on days of extreme precipitation, hypothesising that periods of high rainfall may disrupt access to healthcare services (Samano et al., Citation2021). These three studies suggest that extreme precipitation may be linked with increased risk and prevalence of HIV/STI infections, along with hindered access to care.

Extreme temperature

Ten studies in our review discussed extreme temperature, most (n = 7) focusing on GBV. These studies were split between higher income countries (predominantly the USA) and LMIC. All studies focused on extreme temperature were quantitative.

HIV/STI and extreme temperature

Three of the ten extreme-temperature focused studies assessed links between temperature and HIV and STIs, with mixed results. One study modelled data from 400,000 individuals in 25 countries across SSA, predicting that rising temperatures resulting from climate change will account for up to a 2% increase in HIV prevalence (16 million additional HIV infections) by the year 2050 (Baker, Citation2020). The author posits that the pathways from rising temperatures to HIV acquisition risks include increased men’s migration and increased demand among men for transactional sex – both factors are more prevalent in warmer temperatures. An ecological study in Miami, USA showed that on days of extreme heat, HIV clinic attendance dropped by 14% (Samano et al., Citation2021). However, causality between extreme heat and HIV clinic attendance could not be determined as findings used population-level versus individual-level data. In contrast, an ecological study spanning a 50-year period in China found no correlations between temperature changes and HIV or syphilis incidence (Li et al., Citation2010).

GBV and temperature

Seven studies explored the impact of temperature on rates of GBV, six of which found a positive correlation between the two, with higher rates of GBV reported at higher temperatures. Almost all articles investigated sexual assault or violence (n = 5), with two investigating IPV or intimate partner femicides. The increases in violence were generally seen in the days following the temperature spike. A study in Dallas, USA found a statistically significant U-shaped relationship, with violence increasing with temperatures up to 90 degrees Fahrenheit and dropping off at higher temperatures, a pattern they suggest is due to people finding shelter in cooler spaces, thus reducing the amount of street crime (Gamble & Hess, Citation2012). Conversely, a study on climate data across the USA found a strictly linear relationship between rape and temperature ranging from 0 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit, despite noting a U-shaped relationship in other types of violent crime (Ranson, Citation2014). Studies conducted in Tshwane, South Africa (Schutte & Breetzke, Citation2018), Madrid, Spain (Sanz-Barbero et al., Citation2018), and across seven large US cities (Xu et al., Citation2021) all showed linear relationships between GBV and temperature. Generally, with regard to linear relationships, researchers posit that elevated temperature may increase socialisation, frustration, discomfort, and in turn raise the likelihood of aggression. With U-shaped relationships, researchers posit that above certain temperatures, individuals may be more likely to seek refuge in cooler spaces, reducing social interactions and related crimes.

Fires

In our review, all three studies investigating fires examined GBV outcomes following the Black Saturday bushfires in Australia. Each study revealed perceptions of a surge in violence against women post-disaster, with two qualitative studies noting perceived increases in domestic violence (Parkinson, Citation2019; Parkinson & Zara, Citation2013). One of these qualitative studies noted half of women participants reported IPV – most of whom had not experienced IPV prior to the fires. Those who had experienced IPV prior to the fires reported experiencing escalated post-disaster violence (Parkinson, Citation2019). The one quantitative study found reduced income was most strongly associated with woman reporting violence in areas highly impacted by the fires (Molyneaux et al., Citation2020).

GBV and warning systems

Among the studies focused on GBV, four investigated the relationship between advanced warning systems or strategies and the prevalence of GBV. These warning systems predominantly aimed at addressing three critical areas: (1) enhancing emergency preparedness, which encompassed measures like structural protection, emergency food stockpiles, and evacuation plans; (2) improving knowledge, often through government or local non-profit campaigns or interventions on gender-based violence prevention; and (3) alleviating individual stress associated with the disaster. Advanced warning of a disaster appeared to be protective against GBV in some circumstances, allowing sufficient time for individuals and support organisations to prepare. For example, a mixed-methods study found an association between sandbagging and evacuation in preparation for flooding and no reported increases in domestic violence service demand in Winnipeg, Canada (Enarson, Citation1999). Conversely, one qualitative and one quantitative study found linkages between an advanced warning and increased violence (Rezwana & Pain, Citation2021; Spencer & Strobl, Citation2019). For example, a study using constabulary force databases investigating the relationship between hurricanes and rape reports over a 13 year period in Jamaica found that reports of rape significantly decreased during hurricanes, while storm warning issuance for hurricanes was associated with significantly increased rape reports (Spencer & Strobl, Citation2019). In another example, qualitative respondents in Barguna, Bangladesh widely believed GBV increased before, during, and after cyclones, starting from the time a severe weather warning was issued (Rezwana & Pain, Citation2021). Strategies aimed at preventing and combatting GBV implemented before a typhoon hit in Vietnam were believed by researchers to have had a pre-emptive effect on violence (Nguyen & Rydstrom, Citation2018).

Discussion

Findings from this scoping review of 83 studies exploring the associations between climate change-related factors and sexual health reveal potential multi-level pathways from EWE to poorer HIV/STI outcomes and increased GBV risks. These pathways span structural (e.g. health infrastructure damage), community (e.g. forced relocation), interpersonal (e.g. transactional sex), and intrapersonal (e.g. psychological distress) levels. Several global regions (South America, South Asia, Asia Pacific, Australasia, Europe), sexual health dimensions (comprehensive sexuality education, psychosexual counselling), and EWE (e.g. dust storms, wildfires) were underrepresented in this review, as illustrated in and . Findings can inform future climate-informed sexual health research, intervention, and policy.

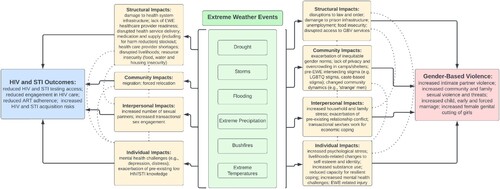

Our findings underscore the utility of applying an ecosocial approach (Krieger, Citation1994, Citation2001) to conceptualise pathways from EWE to sexual health. Ecosocial approaches explore the interacting and diverse pathways that shape adverse exposure to exogenous hazards (such as extreme weather), social and economic challenges, and health care barriers that ultimately shape the patterning of health and disease (Krieger, Citation1994, Citation2001). We applied an ecosocial approach to develop a conceptual framework illustrating mechanistic pathways we identified between EWE and HIV/STI and GBV (). As illustrated in , this conceptual framework details the interconnected pathways connecting EWE to HIV/STI and GBV spanning ecosocial levels. For instance, EWE may influence HIV clinical outcomes among people living with HIV by constraining access to ART via structural (e.g. medication stockout) and intrapersonal (e.g. increased depression) pathways. HIV/STI testing access may be reduced during EWE via structural (e.g. infrastructure damage) factors. EWE may contribute to increased HIV/STI exposure through structural (e.g. increased poverty), community (e.g. migration), and interpersonal (e.g. transactional sex) pathways. While findings varied regarding associations between storms and drought with GBV, most studies that examined flooding, extreme temperatures, and bushfires reported associations with increased GBV. These pathways from EWE to GBV similarly span social-ecological levels including institutional (e.g. disrupted law/social order), community (e.g. exacerbation of inequitable gender norms), interpersonal (e.g. increased household stress), and individual (e.g. increased psychological stress). Importantly, we include intersecting stigma (Berger, Citation2004; Logie et al., Citation2021) as a factor to consider when exploring GBV: our review noted that LGBTQ persons, persons of a lower caste, women (vs. men), and younger persons may experience exacerbated stigma linked with GBV risks after EWE. Our framework aligns with past research on social ecological drivers of GBV (Michau et al., Citation2015) and HIV (Baral et al., Citation2013) to highlight how the mechanistic pathways connecting EWE to sexual health are also multi-level and interacting and thus can inform multi-pronged interventions.

Figure 3. Conceptual framework of pathways between extreme weather events and HIV/STI outcomes and gender-based violence.

Our findings expand the evidence-base regarding climate change and HIV and STI outcomes (Lieber et al., Citation2021). The HIV treatment (Kay et al., Citation2016) and prevention (Moorhouse et al., Citation2019) cascades may be useful frameworks for future EWE research. For instance, the HIV treatment cascade includes: HIV testing as key to diagnosis, yet EWE can damage health infrastructure and subsequently pose testing barriers; engagement and retention in care, which can be disrupted with medication stockouts during EWE; and adherence and viral suppression, whereby EWE such as floods can disrupt access to HIV clinics. Others discussed drought-related food insecurity and livelihoods challenges worsened general health outcomes among PLHIV (Gwatirisa & Manderson, Citation2012; Mazzeo, Citation2008; Orievulu & Iwuji, Citation2021). Less studies have examined pathways connecting EWE to HIV prevention, particularly pathways from EWE to multiple dimensions of HIV prevention cascade (Moorhouse et al., Citation2019), including motivation (e.g. risk perception), access (e.g. availability, affordability), and effective use (e.g. sex efficacy). Our findings that higher HIV prevalence was documented in contexts of drought aligns with prior research that documents drought-related changes in sexual practices and migration contribute to HIV acquisition risk (Low et al., Citation2019). Our findings also corroborate systematic review findings on drought and poorer ART adherence among people living with HIV in SSA (Orievulu et al., Citation2022) and signals the benefit of also examining drought and pathways to HIV prevention. For instance, a recent study of 10 high prevalence SSA countries reported drought was associated with reduced HIV testing and increased condomless sex (Epstein et al., Citation2023). Future studies could thus examine a wider range of EWE and HIV/STI prevention modalities (e.g. pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake).

Our findings build on past reviews of linkages between EWE and higher GBV (Rezaeian, Citation2013; Thurston et al., Citation2021; Van Daalen et al., Citation2022). Our review notes variability in pathways to GBV by EWE, for instance drought may elevate drivers of food insecurity (structural level) while storm-related forced relocation can increase exposure to sexual harassment (community level) (see ). Our findings corroborate disaster-related GBV drivers identified in other reviews (e.g. stress, economic insecurity, gender inequity) (Rezaeian, Citation2013; Thurston et al., Citation2021; van Daalen et al., Citation2021) and expand this evidence base by illustrating how these drivers can vary by EWE across ecosocial levels. Notably, climate change-related factors do not cause GBV, rather they exacerbate existing social inequities (e.g. gender inequity, LGBTQ marginalisation) that in turn create enabling environments for GBV to occur.

Revisiting the conceptual frameworks guiding this review, our findings align with Lieber’s hypothesised impacts of EWE – particularly droughts and hurricanes – on migration, infrastructure erosion, and food insecurity in ways that can increase HIV/STI acquisition and worsen HIV/STI outcomes. This conceptual model (Lieber et al., Citation2021) also posited that climate change would result in higher infectious disease prevalence that could worsen health outcomes among PLHIV – this was an understudied area in studies included in our review. STIs are also largely understudied, with only syphilis and gonorrhea examined. While ecosydemic interactions (Tallman et al., Citation2022) were not discussed in included studies, our findings suggest the promise of empirically testing bio-social (e.g. GBV and HIV/STI acquisition) and bio-bio (e.g. schistosomiasis and viral suppression) interactions. Our review also corroborates Women Deliver’s (Citation2021) framework where climate-change related household stress can worsen GBV, including child, early and forced marriage; their hypothesised pathway from mobility and migration to trafficking remains understudied and warrants further empirical investigation.

This review identified several persisting research gaps. Firstly, there was a lack of attention to key populations who experience sexual health disparities, including sex workers, LGBTQ persons, people who use drugs, and individuals living with a disability – particularly in LMIC. There was a dearth of studies reporting on participants’ ethno-racial identity and a lack of investigation into the intersection of EWE with racial discrimination. As climate change most impacts socially marginalised communities (IPCC, Citation2022; Romanello et al., Citation2021), and can exacerbate existing social and health disparities (Lieber et al., Citation2021; Romanello et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2018; Whitmee et al., Citation2015; Women Deliver, Citation2021), including key populations affected by sexual health disparities in climate change sexual health research is essential to advance health equity. Without adequate research representation, the unique needs of these groups may remain invisible, reproducing policy exclusion that can re/produce existing inequities. Additionally, a recent climate migration and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) review noted a lack of primary data collection and called for research with all genders on diverse SRH health outcomes among climate migrants (van Daalen et al., Citation2021). Some topics, such as extreme temperature and linkages with GBV and HIV/STI, and extreme precipitation and linkages with HIV/STI, were only examined in quantitative studies () and in some regions (), reflecting the need for qualitative and mixed-methods studies on additional EWE across geographies to gain in-depth insight into vulnerabilities and protective factors. There is also a need for more longitudinal mixed-methods studies to examine EWE to better identify mechanistic pathways and understand trajectories of sexual health risks and resiliency for a diversity of populations and contexts. This can in turn inform intervention research – there is a dearth of climate-informed sexual health interventions. Together, findings signal that climate change and sexual health research may be strengthened by examining multi-faceted sexual health dimensions globally using mixed-method approaches across a range of climate change issues.

Figure 4. Joint display of qualitative and quantitative scoping review findings on associations between climate change and sexual health.

Strengths and limitations

Our review of climate change and sexual health builds on previous reviews focused on one dimension of sexual health (e.g. ART adherence, GBV) and/or singular climate event (e.g. drought) or response (e.g. climate migration) by comprehensively examining sexual health. We identify knowledge gaps, particularly regarding EWE with comprehensive sexuality education and sexual function and psychosexual counselling. This review also has limitations. As the focus was on climate change-related events, other natural and human-made disasters that might impact sexual health, such as earthquakes and oil spills, were not captured. Though we did not limit studies by language, our search terms were in English, which may have limited our identification of articles published in other languages and might contribute to the overrepresentation of articles from North America. In keeping with standard scoping review approaches, study quality was not assessed, which might also be considered a limitation.

Conclusions

Our scoping review findings can support theoretically informed research exploring a range of climate-related issues potentially relevant to sexual health including greenhouse gases, temperature, sea levels, natural disasters, dust storms, floods, heat waves, deforestation, land degradation, and a loss of biodiversity. Future studies can examine a range of climate change-related sexual health outcomes. Examining climate resilience – the ability of individuals and their communities to anticipate, cope with, and adapt to climatic events and environmental changes (Masson et al., Citation2019) – is urgently needed in the context of sexual health. Creative climate-informed sexual health strategies can be co-developed with affected communities building on existing early warning systems (Lowe et al., Citation2011). For instance, contextually, gender and age tailored GBV prevention strategies can be integrated within early warning systems. Self-care SRH strategies (Narasimhan et al., Citation2019) could be also integrated into early warning systems; for instance, if droughts are linked with increased migration, mobile health could be used to inform community members of upcoming drought, related sexual health issues, and action planning (e.g. securing sufficient ART prior to migration). Similar to humanitarian settings, when storms, flooding or other health infrastructure disruptions are expected, self-care SRH strategies such as HIV self-testing could be distributed in advance to increase access (Logie et al., Citation2019). Identifying social ecological protective resources can inform multi-level strategies that leverage community strengths, resilience, and cohesion to ensure contextual relevance and long-term sustainability. Global health research can consider the effects of climate change and EWE to ensure that the changing, multi-level drivers of sexual health and wellbeing are centred and addressed.

Author’s contributions

CHL conceptualised the study and led the writing. DT led the scoping review search and extraction process and substantially contributed to writing the manuscript. HD, NL, KM conducted the search and extraction. KM also substantially contributed to writing the manuscript. FM, AH, and MN contributed substantially to the revision process and to editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the University of Toronto librarians.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abah, R. C., & Petja, B. M. (2016). Assessment of potential impacts of climate change on agricultural development in the Lower Benue River Basin. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 188(12), 683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-016-5700-x

- Ahmed, K. J., Haq, S. M. A., & Bartiaux, F. (2019). The nexus between extreme weather events, sexual violence, and early marriage: A study of vulnerable populations in Bangladesh. Population and Environment, 40(3), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-019-0312-3

- Alam, K., & Rahman, H. (2014). Women in natural disasters: A case study from southern coastal region of Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 8, 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.01.003

- Alburo-Cañete, K. Z. K. (2014). Bodies at risk: “Managing” sexuality and reproduction in the aftermath of disaster in the Philippines Kaira. Gender, Technology and Development, 18(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852413515356

- Allen, E. M., Munala, L., & Henderson, J. R. (2021). Kenyan Women Bearing the Cost of Climate Change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 12697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312697

- Anastario, M., Shehab, N., & Lawry, L. (2009). Increased gender-based violence among women internally displaced in Mississippi 2 years post-Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 3(1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181979c32

- Anastario, M. P., Larrance, R., & Lawry, L. (2008). Using mental health indicators to identify postdisaster gender-based violence among women displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Women's Health, 17(9), 1437–1444. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0694

- Anthonj, C., Nkongolo, O. T., Schmitz, P., Hango, J. N., & Kistemann, T. (2015). The impact of flooding on people living with HIV: A case study from the Ohangwena Region, Namibia. Global Health Action, 8(1), 26441. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.26441

- Asadullah, M. N., Islam, K. M. M., & Wahhaj, Z. (2021). Child marriage, climate vulnerability and natural disasters in coastal Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science, 53(6), 948–967. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932020000644

- Austin, K. F., Noble, M. D., & Berndt, V. K. (2021). Drying climates and gendered suffering: Links between drought, food insecurity, and women's HIV in less-developed countries. Social Indicators Research, 154(1), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02562-x

- Azad, A. K., Hossain, K. M., & Nasreen, M. (2013). Flood-induced vulnerabilities and problems encountered by women in northern Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 4, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-013-0020-z

- Baker, R. E. (2020). Climate change drives increase in modeled HIV prevalence. Climatic Change, 163(1), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02753-y

- Baral, S., Logie, C. H., & Grosso, A. (2013). Modified social ecological model: A tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health, 13, 482. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-482

- Beek, K., Drysdale, R., Kusen, M., & Dawson, A. (2021). Preparing for and responding to sexual and reproductive health in disaster settings: Evidence from Fiji and Tonga. Reproductive Health, 18(185), (no pagination). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01236-2

- Bell, J. E., Brown, C. L., Conlon, K., Herring, S., Kunkel, K. E., Lawrimore, J., Luber, G., Schreck, C., Smith, A., & Uejio, C. (2018). Changes in extreme events and the potential impacts on human health. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 68, 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2017.1401017

- Berger, M. T. (2004). Workable Sisterhood: The Political Journey of Stigmatized Women With HIV/AIDS. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592705230499 Google Scholar.

- Bermudez, L. G., Stark, L., Bennouna, C., Jensen, C., Potts, A., Kaloga, I. F., Tilus, R., Buteau, J. E., Marsh, M., Hoover, A., & Williams, M. L. (2019). Converging drivers of interpersonal violence: Findings from a qualitative study in post-hurricane Haiti. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.003

- Berndt, V. K., & Austin, K. F. (2021). Drought and disproportionate disease: an investigation of gendered vulnerabilities to HIV/AIDS in less-developed nations. Population and Environment, 42(3), 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-020-00367-1

- Bradley, T., Martin, Z., Upreti, B. R., Subedu, B., & Shrestha, S. (2023). Gender and disaster: The impact of natural disasters on violence against women in Nepal. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 58(3), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211062474

- Burke, M., Gong, E., & Jones, K. (2015). Income shocks and HIV in Africa. The Economic Journal, 125(585), 1157–1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12149

- Carrico, A. R., Donato, K. M., Best, K. B., & Gilligan, J. (2020). Extreme weather and marriage among girls and women in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change, 65, 102160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102160

- Clark, R. A. (2006). Eight months later: Hurricane Katrina aftermath challenges facing the Infectious Diseases Section of the Louisiana State University Health Science Center. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 43. https://doi.org/10.1086/505980

- Clark, R. A., Besch, L., & Murphy, M., et al. (2006). Six months later: The effect of Hurricane Katrina on health care for persons living with HIV/AIDS in New Orleans. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120600838688

- Clark, R. A., Broyles, S., & Besch, L. (2007). Differences in the pre- and post-Katrina New Orleans HIV outpatient clinic population: Who has returned? Southern Medical Journal, 100. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3180619367

- Clark, R. A., Mirabelli, R., Shafe, J., Broyles, S., Besch, L., & Kissinger, P. (2007). The New Orleans HIV outpatient program patient experience with Hurricane Katrina. Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society, 159(5), 276–281. PMID: 18220096.

- Cools, S., Flato, M., & Kotsadam, A. (2020). Rainfall shocks and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 57(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319880252

- Corno, L., Hildebrandt, N., & Voena, A. (2020). Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments. Econometrica, 88(3), 879–915. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA15505

- Cruess, S., Antoni, M., Kilbourn, K., Ironson, G., Klimas, N., Fletcher, M. A., Baum, A., & Schneiderman, N. (2000). Optimism, distress, and immunologic status in HIV-infected gay men following Hurricane Andrew. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 7(2), 160–182. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327558IJBM0702_5

- Díaz, J. J., & Saldarriaga, V. (2023). A drop of love? Rainfall shocks and spousal abuse: Evidence from rural Peru. Health Economics, 89, 102739 (no pagination). ISSN 0167-6296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2023.102739

- Dwyer, E., & Woolf, L. (2018). Down By The River: Addressing the Rights, Needs and Strengths of Fijian Sexual and Gender Minorities in Disaster Risk Reduction and Humanitarian Response. Victoria: Oxfam Australia. Downloaded from: https://www.edgeeffect.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Down-By-The-River_Web.pdf.

- Dzomba, A., Govender, K., Mashamba-Thompson, T. P., & Tanser, F. (2018). Mobility and increased risk of HIV acquisition in South Africa: A mixed-method systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 7, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0703-z

- Ekperi, L. I., Thomas, E., LeBlanc, T. T., Adams, E. E., Wilt, G. E., Molinari, N. A., & Carbone, E. G. (2018). The Impact of Hurricane Sandy on HIV Testing Rates: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, January 1, 2011‒December 31, 2013. PLoS Curr, 10, ecurrents.dis.ea09f9573dc292951b7eb0cf9f395003. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.ea09f9573dc292951b7eb0cf9f395003. PMID: 30338170; PMCID: PMC6160290.

- Enarson, E. (1999). Violence against women in disasters: A study of domestic violence programs in the United States and Canada. Violence Against Women, 5(7), 742–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778019922181464

- Epstein, A., Bendavid, E., Nash, D., Charlebois, E. D., & Weiser, S. D. (2020). Drought and intimate partner violence towards women in 19 countries in sub-Saharan Africa during 2011–2018: A population-based study. PLoS Medicine, 17(3), e1003064. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003064

- Epstein, A., Nagata, J. M., Ganson, K. T., Nash, D., Saberi, P., Tsai, A. C., Charlebois, E. D., & Weiser, S. D. (2023). Drought, HIV testing, and HIV transmission risk behaviors: A population-based study in 10 high HIV prevalence countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 27(3), 855–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03820-4

- Esho, T., Komba, E., Richard, F., & Shell-Duncan, B. (2021). Intersections between climate change and female genital mutilation among the Maasai of Kajiado County, Kenya. Journal of Global Health, 11, 04033. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.04033

- Fagen, J. L., Sorensen, W., & Anderson, P. B. (2011). Why not the University of New Orleans? Social disorganization and sexual violence among internally displaced women of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Community Health, 36(5), 721–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9365-7

- Fothergill, A. (1999). An exploratory study of woman battering in the Grand Forks flood disaster: Implications for community responses and policies. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 17(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072709901700105

- Frasier, P. Y., Belton, L., Hooten, E., Campbell, M. K., DeVellis, B., Benedict, S., Carrillo, C., Gonzalez, P., Kelsey, K., & Meier, A. (2004). Disaster down east: Using participatory action research to explore intimate partner violence in eastern North Carolina. Health Education & Behavior, 31(4), 69S–84S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104266035

- Gamble, J. L., & Hess, J. J. (2012). Temperature and violent crime in Dallas, Texas: Relationships and implications of climate change. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(3), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2012.3.11746

- Geyer, N. R., Margaritis, V., & Rea, N. K. (2018). Characteristics of HIV screening among New Jersey adults aged 18 years or older post-Hurricane Sandy, 2014. Public Health, 155, 59–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.11.017

- Gwatirisa, P., & Manderson, L. (2012). “Living from Day to Day”: Food insecurity, complexity, and coping in Mutare, Zimbabwe. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 51(2), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2012.661328

- Hammett, J. F., Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2022). Effects of hurricane harvey on trajectories of hostile conflict among newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(7), 1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0001000

- Harville, E. W., Taylor, C. A., Tesfai, H., Xiong, X., & Buekens, P. (2011). Experience of Hurricane Katrina and reported intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(4), 833–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510365861

- Hossen, M. A., Benson, D., Hossain, S. Z., & Sultana, Z. (2021). Gendered perspectives on climate change adaptation: A quest for social sustainability in Badlagaree village. Bangladesh, 13, 1922.

- Infectious Diseases Section, Louisiana State University Health Science Center. (2006). Eight months later: Hurricane Katrina aftermath challenges facing the Infectious Diseases Section of the Louisiana State University Health Science Center. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 43(4), 485–489. https://doi.org/10.1086/505980

- IPCC. (2022). Summary for policymakers. In D. C. R. H.-O. Pörtner, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, M. C. A. Alegría, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, & A. Okem (Eds.), Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (pp. 3–33). Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Kay, E. S., Batey, D. S., & Mugavero, M. J. (2016). The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: Updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Research and Therapy, 13, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-016-0120-0

- Khawcharoenporn, T., Apisarnthanarak, A., Chunloy, K., & Mundy, L. M. (2013). Access to antiretroviral therapy during excess black-water flooding in central Thailand. AIDS Care, 25(11), 1446–1451. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.772284

- Kilbourn, K. M. (1997). The effects of hurricane Andrew on coping, distress, immune and endocrine factors in a group of HIV+ gay men. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 57(12-B), 7733.

- Krieger, N. (1994). Epidemiology and the web of causation: Has anyone seen the spider? Social Science & Medicine, 39(7), 887–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-X

- Krieger, N. (2001). Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: An ecosocial perspective. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.4.668

- Li, X. H., Gao, L. L., Dai, L., Zhang, G. Q., Zhuang, X. S., Wang, W., & Zhao, Q. J. (2010). Understanding the relationship among urbanisation, climate change and human health: A case study in Xiamen. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 17(4), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2010.493711

- Lieber, M., Chin-Hong, P., Whittle, H. J., Hogg, R., & Weiser, S. D. (2021). The synergistic relationship between climate change and the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A conceptual framework. AIDS and Behavior, 25, 2266–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03155-y

- Lobell, D. B., Burke, M. B., Tebaldi, C., Mastrandrea, M. D., Falcon, W. P., & Naylor, R. L. (2008). Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science, 319, 607–610. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152339

- Logie, C. H., Khoshnood, K., Okumu, M., Rashid, S. F., Senova, F., Meghari, H, et al. (2019). Self care interventions could advance sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian settings. BMJ, 365, l1083. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1083

- Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Kibuuka Musoke, D., Hakiza, R., Mwima, S., Kyambadd, P., Abela, H., Gittings, L., Musinguzi, J., Mbuagbaw, L., & Baral, S. (2021). Intersecting stigma and HIV testing practices among urban refugee adolescents and youth in Kampala, Uganda: Qualitative findings. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(3), e25674. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25674

- Logie, C. H., Toccalino, D., Reed, A. C., Malama, K., Newman, P. A., Weiser, S., Harris, O., Berry, I., & Adedimeji, A. (2021, Oct 18). Exploring linkages between climate change and sexual health: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 11(10), e054720. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054720. PMID: 34663670; PMCID: PMC8524293.

- Low, A. J., Frederix, K., McCracken, S., Manyau, S., Gummerson, E., Radin, E., Davia, S., Longwe, H., Ahmed, N., Parekh, B., Findley, S., & Schwitters, A. (2019). Association between severe drought and HIV prevention and care behaviors in Lesotho: A population-based survey 2016–2017. PLoS Medicine, 16(1), e1002727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002727

- Lowe, D., Ebi, K. L., & Forsberg, B. (2011). Heatwave early warning systems and adaptation advice to reduce human health consequences of heatwaves. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8, 4623–4648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8124623

- Luetke, M., Judge, A., Kianersi, S., Jules, R., & Rosenberg, M. (2020). Hurricane impact associated with transactional sex and moderated, but not mediated, by economic factors in Okay, Haiti. Social Science & Medicine, 261, 113189, Article 113189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113189

- Madhuri. (2016). The impact of flooding in Bihar, India on women: A qualitative study. Asian Women, 32(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2016.03.32.1.31

- Madkour, A. S., Johnson, C. C., Clum, G. A., & Brown, L. (2011). Disaster and youth violence: The experience of school-attending youth in New Orleans. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(2), 213–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.06.005

- Masson, V. L., Benoudji, C., Reyes, S. S., & Bernard, G. (2019). How violence against women and girls undermines resilience to climate risks in Chad. Disasters, 43(Supplement 3), S245–S270. http://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12343

- Mazzeo, J. (2008). The impact of HIV=IDS on the Shona livelihood system of Southeast Zimbabwe. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 68(10-A), 4362.

- McCrudden, M. T., Marchand, G., & Schutz, P. A. (2021). Joint displays for mixed methods research in psychology. Methods in Psychology, 5, 100067.

- McMichael, C., Barnett, J., & McMichael, A. J. (2012). An Ill wind? Climate change, migration, and health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(5), 646–654. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104375

- Michau, L., Horn, J., Bank, A., Dutt, M., & Zimmerman, C. (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. The Lancet, 385(9978), 1672–1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61797-9

- Molyneaux, R., Gibbs, L., Bryant, R. A., Humphreys, C., Hegarty, K., Kellett, C., Gallagher, H. C., Block, K., Harms, L., Richardson, J. F., Alkemade, N., & Forbes, D. (2020). Interpersonal violence and mental health outcomes following disaster. Bjpsych Open, 6(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.82

- Moorhouse, L., Schaefer, R., Thomas, R., Nyamukapa, C., Skovdal, M., Hallett, T. B., & Gregson, S. (2019). Application of the HIV prevention cascade to identify, develop and evaluate interventions to improve use of prevention methods: Examples from a study in east Zimbabwe. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(S4), e25309. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25309

- Mugglin, C., Kläger, D., Gueler, A., Vanobberghen, F., Rice, B., & Egger, M. (2021). The HIV care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of published criteria and definitions. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24, e25761. https://doi.org/10.1002/JIA2.25761

- Nagata, J. M., Hampshire, K., Epstein, A., Lin, F., Zakaras, J., Murnane, P., Charlebois, E. D., Tsai, A. C., Nash, D., & Weiser, S. D. (2022). Analysis of heavy rainfall in Sub-Saharan Africa and HIV transmission risk, HIV prevalence, and sexually transmitted infections, 2005–2017. JAMA Network Open, 5(9), e2230282. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.30282

- Narasimhan, M., Allotey, P., & Hardon, A. (2019). Self care interventions to advance health and wellbeing: A conceptual framework to inform normative guidance. BMJ, 365, l688. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l688

- Nguyen, H. T. (2019). Gendered vulnerabilities in times of natural disasters: Male-to-female violence in the Philippines in the aftermath of super typhoon Haiyan. Violence Against Women, 25(4), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218790701

- Nguyen, H. T., & Rydstrom, H. (2018). Climate disaster, gender, and violence: Men's infliction of harm upon women in the Philippines and Vietnam. Women's Studies International Forum, 71, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.09.001

- Nsuami, M. J., Taylor, S. N., Smith, B. S., & Martin, D. H. (2009). Increases in gonorrhea among high school students following hurricane Katrina. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(3), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2008.031781

- Orievulu, K. S., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Ngema, S., Baisley, K., Tanser, F., Ngwenya, N., Seeley, J., Hanekom, W., Herbst, K., Kniveton, D., & Iwuji, C. C. (2022). Exploring linkages between drought and HIV treatment adherence in Africa: a systematic review. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(4), e359–e370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00016-X

- Orievulu, K. S., & Iwuji, C. C. (2021). Institutional responses to drought in a high HIV prevalence setting in rural South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health [Electronic Resource], 19(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010434

- Padilla, M., Rodriguez-Madera, S. L., Varas-Diaz, N., Grove, K., Rivera, S., Rivera, K., Contreras, V., Ramos, J., & Vargas-Molina, R. (2022). Red tape, slow emergency, and chronic disease management in post-María Puerto Rico. Critical Public Health, 32(4), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2021.1998376

- Parkinson, D. (2019). Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: An Australian case study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(11), 2333–2362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517696876

- Parkinson, D., & Zara, C. (2013). The hidden disaster: Domestic violence in the aftermath of natural disaster. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 28(2), 28–35.

- Phalkey, R. K., Aranda-Jan, C., Marx, S., Hölfe, B., & Sauerborn, R. (2015). Systematic review of current efforts to quantify the impacts of climate change on undernutrition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(33), E4522–E4529. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1409769112

- Picardo, C. W., Burton, S., Naponick, J., & Katrina Reproductive Assessment Team. (2010, Sep.-Oct.). Physically and sexually violent experiences of reproductive-aged women displaced by Hurricane Katrina. The Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society: Official Organ of the Louisiana State Medical Society, 162(5), 282. 284–288, 290. PMID: 21141260.

- Potgieter, A., Fabris-Rotelli, I. N., Breetzke, G., & Wright, C. Y. (2022). The association between weather and crime in a township setting in South Africa. International Journal of Biometeorology, 66(5), 865–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-022-02242-0

- Pouget, E. R., Sandoval, M., Nikolopoulos, G. K., & Friedman, S. R. (2015). Immediate impact of Hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(7), 878–884. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.978675

- Rai, A., Sharma, A. J., & Subramanyam, M. A. (2021). Droughts, cyclones, and intimate partner violence: A disastrous mix for Indian women. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 53, 102023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.102023

- Ranson, M. (2014). Crime, weather, and climate change. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 67(3), 274–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2013.11.008

- Rashid, S. F., & Michaud, S. (2000). Female adolescents and their sexuality: Notions of honour, shame, purity and pollution during the floods. Disasters, 24(1), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00131

- Reilly, K. H., Clark, R. A., Schmidt, N., Benight, C. C., & Kissinger, P. (2009). The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on HIV disease progression following Hurricane Katrina. AIDS Care, 21(10), 1298–1305. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120902732027

- Rezaeian, M. (2013). The association between natural disasters and violence: A systematic review of the literature and a call for more epidemiological studies. Journal of Research Medical Sciences, 18(12), 1103–1107.

- Rezwana, N., & Pain, R. (2021). Gender-based violence before, during, and after cyclones: Slow violence and layered disasters. Disasters, 45(4), 741–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12441

- Robinson, W. T., Wendell, D., & Gruber, D. (2011). Changes in CD4 count among persons living with HIV/AIDS following Hurricane Katrina. AIDS Care, 23(7), 803–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.534437

- Romanello, M., McGushin, A., Di Napoli, C., Drummond, P., Hughes, N., Jamart, L., Kennard, H., Lampard, P., Solano Rodriguez, B., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Belesova, K., Cai, W., Campbell-Lendrum, D., Capstick, S., Chambers, J., Chu, L., Ciampi, L., Dalin, C., … Hamilton, I. (2021). The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. The Lancet, 398(10311), 1619–1662. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6

- Samano, D., Saha, S., Kot, T. C., Potter, J. E., & Duthely, L. M. (2021). Impact of extreme weather on healthcare utilization by people with HIV in metropolitan Miami. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2441–2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052442

- Sanz-Barbero, B., Linares, C., Vives-Cases, C., Gonzalez, J. L., Lopez-Ossorio, J. J., & Diaz, J. (2018). Heat wave and the risk of intimate partner violence. Science of the Total Environment, 644, 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.368

- Schumacher, J. A., Coffey, S. F., Norris, F. H., Tracy, M., Clements, K., & Galea, S. (2010). Intimate partner violence and Hurricane Katrina: Predictors and associated mental health outcomes. Violence and Victims, 25(5), 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.588

- Schutte, F. H., & Breetzke, G. D. (2018). The influence of extreme weather conditions on the magnitude and spatial distribution of crime in Tshwane (2001–2006). South African Geographical Journal, 100(3), 364–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2018.1498384

- Sharpe, J. D. (2019). A comparison of the geographic patterns of HIV prevalence and hurricane events in the United States. Public Health, 171, 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.04.001

- Singh, D. (2020). Gender relations, urban flooding, and the lived experiences of women in informal urban spaces. Asian Journal of Women's Studies, 26(3), 326–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2020.1817263

- Singh, N. S., Aryasinghe, S., Smith, J., Khosla, R., Say, L., & Blanchet, K. (2018). A long way to go: A systematic review to assess the utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian crises. BMJ Global Health 3, e000682. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000682

- Sohrabizadeh, S. (2016). A qualitative study of violence against women after the recent disasters of Iran. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 31(4), 407–412. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X16000431

- Spencer, N., & Strobl, E. (2019). Crime watch: Hurricanes and illegal activities. Southern Economic Journal, 86(1), 318–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12376

- Stanke, C., Kerac, M., Prudhomme, C., Medlock, J., & Murray, V. (2013, Jun 5). Health effects of drought: A systematic review of the evidence. PLoS Currents, 5(5), ecurrents.dis.7a2cee9e980f91ad7697b570bcc4b004. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.7a2cee9e980f91ad7697b570bcc4b004.

- Stephenson, R., Gonsalves, L., Askew, I., & Say, L. (2017). Detangling and detailing sexual health in the SDG era. The Lancet, 390(10099), 1014–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32294-8

- Tallman, P. S., Riley-Powell, A. R., Schwarz, L., Salmón-Mulanovich, G., Southgate, T., Pace, C., Valdés-Velásquez, A., Hartinger, S. M., Paz-Soldán, V. A., & Lee, G. O. (2022). Ecosyndemics: The potential synergistic health impacts of highways and dams in the Amazon. Social Science & Medicine, 295, 113037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113037

- Tanyag, M. (2018). Resilience, female altruism, and bodily autonomy: Disaster-induced displacement in post-Haiyan Philippines. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 43(3), 563–585. https://doi.org/10.1086/695318

- Temple, J. R., van den Berg, P., Fred” Thomas, J. F., Northcutt, O. M. J., Thomas, C., & Freeman, D. H., Jr. (2011). Teen dating violence and substance use following a natural disaster: Does evacuation status matter? American Journal of Disaster Medicine, 6, 201–206. https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2011.0059

- Thurston, A. M., Stöckl, H., & Ranganathan, M. (2021). Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: A global mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 6(4), e004377. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004377

- True, J. (2013). Gendered violence in natural disasters: Learning from New Orleans, Haiti and Christchurch. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 25(2), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol25iss2id83