ABSTRACT

This cross-sectional study is the first to describe the prevalence of violence and poly-victimisation among 310 female sex workers (FSWs) who were cisgender in Haiphong, Viet Nam. An adapted version of the WHO-Multi-Country Study on Violence against Women Survey Instrument was administered to assess physical, sexual, economic and emotional forms of violence perpetrated by an intimate partner, paying partner/client, and/or others (e.g. relatives, police, strangers and other FSWs) during adulthood. The ACE-Q scale was administered to assess adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) before age 18 years. Our findings showed that FSWs are exposed to high rates of multiple forms of violence by multiple perpetrators. For any male client-perpetrated violence (CPV), lifetime prevalence was 70.0%, with 12-month prevalence 61.3%. Lifetime prevalence of male intimate partner violence (IPV) was 62.1%, and the 12-month prevalence was 58.2%. Lifetime and prior 12-month prevalence of physical and/or sexual violence by other perpetrators (OPV) was 18.1% and 14.2%, respectively. Sixty-five percent of FSWs reported at least one type of ACE. Overall, 21.6 percent of FSWs reported having experienced all three forms of violence (IPV, CPV and OPV) in their lifetime. Policy and programme recommendations for screening and prevention of violence are needed in this setting.

Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) is any harmful threat or act directed at an individual or group based on actual or perceived biological sex, gender identity and/or expression, sexual orientation, and/or lack of adherence to varying socially constructed gender norms (UNAIDS, Citation2022). GBV is rooted in structural gender inequalities and characterised by the use or threat of physical, psychological, sexual, economic, legal, political, social and other forms of control or abuse (Krug et al., Citation2002). GBV affects individuals across the life course and has direct and indirect costs to families, communities, economies, global public health and development (Devries et al., Citation2013; García-Moreno et al., Citation2013; Vos et al., Citation2015). Moreover, GBV is a violation of human rights that can be life-threatening and requires close attention, especially in vulnerable populations.

In Viet Nam, GBV is prevalent among women. According to the 2019 National Study on Violence Against Women (n = 5553), 62.9% of Vietnamese women experienced some form of violence during their lifetime, with 31.6% reporting having experienced violence during last 12 months by a husband or intimate partner, though these findings are likely underestimates (MOLISA, GSO and UNFPA, Citation2020). Because of this large burden, Viet Nam has been proactive in addressing the problem of GBV and policy frameworks are in place (Eileen et al., Citation2017).

Female sex workers (FSWs) are at increased risk of exposure to multiple forms of GBV, including emotional, economic, sexual and physical violence (Barnard et al., Citationn.d.; Decker et al., Citation2021; Footer et al., Citation2019; Garcia-Moreno et al., Citation2006; Hail-Jares et al., Citation2015; Leis et al., Citation2021; Panchanadeswaran et al., Citation2008; Peitzmeier et al., Citation2021; Penfold et al., Citation2005; Semple et al., Citation2015; Ulibarri et al., Citation2019). Besides two main perpetrator types – clients and intimate partners (Hail-Jares et al., Citation2015; Jewkes et al., Citation2021; Panchanadeswaran et al., Citation2008; Ulibarri et al., Citation2019), other perpetrators have also been reported in some studies such as family members, friends, peers and neighbours, strangers, other sex workers, health care workers, police, religious leaders and teachers (Decker et al., Citation2021; Peitzmeier et al., Citation2021; Semple et al., Citation2015). Despite the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) calling for the decriminalisation of sex work, and recognising the longstanding promotion by public health advocates and sex workers for safer conditions and protection from violence, in many low and middle income countries (LMICs), sex work remains criminalised and this population continues to experience high levels of violence (Decker et al., Citation2016; Jewkes et al., Citation2021; Maclin et al., Citation2023; Roberts et al., Citation2018). FSWs also often face multiple forms of stigma, including self-stigma (e.g. shame) and social stigma (e.g. negativetreatment by others) (Huber et al., Citation2019; Kerrigan et al., Citation2021). In part due to stigma, and criminalisation associated with sex work, FSWs rarely disclose experiences of GBV to members of their social networks, nor are they likely to seek help (Katsulis et al., Citation2010; McBride et al., Citation2020). Unaddressed GBV can lead to major social problems (e.g. poverty), and health problems (e.g. alcohol and drug use, unsafe sexual behaviours, sexually transmitted infections, HIV infected and mental health) (Beattie et al., Citation2010; Leis et al., Citation2021; Panchanadeswaran et al., Citation2008; Roberts et al., Citation2018; Shahmanesh et al., Citation2009). Thus, an urgent need exists to screen, prevent, and respond to GBV among FSWs.

There are approximately 86,000 FSW in Viet Nam (2020) (PERFAR, Citation2020). However, the prevalence of GBV among sex workers in Viet Nam has not been explicitly measured. As sex work is illegal in Viet Nam, FSWs often are forced to live a hidden existence, cut off from their families and the community, and forced to hide their sex work (Huber et al., Citation2019; Rushing et al., Citation2005). Their rights are not protected, forcing them to sell sex in unsafe situations, such as working alone, working in darker, less public or unfamiliar areas, and spending less time negotiating for safe sex and checking clients for danger signs, such as drunkenness or aggressive behaviour (Huber et al., Citation2019; Ngo et al., Citation2007; Rosenthal & Oanha, Citation2006; Rushing et al., Citation2005). Moreover, FSWs may self-stigmatize, accepting the blame of society and high risk of HIV exposure, contributing further to their isolation and vulnerability to violence (Huber et al., Citation2019; Jafari et al., Citation2019). Given the vulnerability of this population and the compounding stigma, few studies have reported on violence prevalence against FSWs, although some evidence is available on other health outcomes in Viet Nam.

In Haiphong city, located in North Viet Nam with a population of two million, a cross-sectional study conducted in 2012 among 300 FSWs age 18 or older found that 77.4% of the women reported not using condom during their most recent sexual encounter with a client. In terms of drug use, 75.0% of those reported injecting drugs did not receive or use new needles in the last 6 months, 29.0% were never tested for HIV, and the HIV seroprevalence was 1.6% (Nguyen et al., Citation2016). Thus, the high social vulnerability and health risk behaviours of FSW in Haiphong need to be addressed to reduce HIV transmission and to promote public health alongside GBV preventions efforts.

Poly-victimisation, defined as experiencing multiple different types of violence, crime, abuse, or victimisation, is a concept that originated in child abuse research but has also been studied in other vulnerable populations, including FSWs (Coetzee et al., Citation2017; Finkelhor et al., Citation2009; Peitzmeier et al., Citation2021). These studies showed that children often experience multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), which are in turn often risk factors for experiencing other types of violence, leading to a clustering of violence in individuals and an increasing cumulative burden on health in adulthood. Among FSWs, there is evidence of high levels of poly-victimisation, where multiple forms of violence co-occur and interact with each other. For example, client violence may drive exposure to other types of violence and enable poly-victimisation in a way that different types of violence do not in this setting (Peitzmeier et al., Citation2021). Additionally, the prevalence of violence experienced after the first sexual encounter of FSWs may be associated with sexual violence during their first sexual experience (Becker et al., Citation2018). To the best of our knowledge, no study assesses poly-victimisation among FSWs in Viet Nam, despite the fact that FSWs frequently face multiple types of violence [23]. In this study, a poly-victimisation framework was applied to FSW to develop a comprehensive understanding of their experiences of violence victimisation, including ACEs in childhood and GBV in adulthood. Four types of GBV in adulthood were assessed, including sexual violence (SV), physical violence (PV), emotional violence (EV) and economic violence (EcV), as was the perpetrator’s relationship to FSW.

Material and methods

Study design

We employed a cross-sectional, quantitative design to investigate the study objectives. The sample size consisted of 310 active FSWs, all of whom work in urban areas within Haiphong city. Recruitment was done in partnership with community-based organisations (CBOs) throughout the city and at locations such as bars, brothels, hotels and motels, alleys, and street corners.

Setting

The study was conducted in seven urban districts in Haiphong, where CBOs engage in various activities to support FSWs. Haiphong, located in North Viet Nam, is the third most populous city in the country, with a metropolitan area population of 2,103,500 as of 2015. The city covers an area of 1507.57 km2. Approximately 46.1% of residents reside in the seven urban districts comprising the metropolitan area. Because sex work is illegal in Viet Nam, many FSWs choose to live in densely populated urban areas such as Haiphong.

Study population recruitment and procedures

The target population included FSWs in Haiphong city, who were cisgender women, at least 18 years of age, self-identified as FSW, and reported having traded sex for money, drugs, shelter, or other material benefit within the past month. Time-location sampling was used to recruit approximately 50 participants from each district, resulting in a total of 310 FSWs. This sampling approach has been successfully used in prior studies in Viet Nam (Johnston et al., Citation2006; Le et al., Citation2016; Nguyen et al., Citation2009). Trained CBO members compiled a map of venues including bars, brothels, hotels and motels, alleys, and street corners, which served as the sampling frame for identifying potential FSWs in each district. Interested and eligible FSWs were referred by CBO members to the study site, where the study procedures were conducted. Visits were organised at one of two CBO offices (community sites) in Haiphong city from October to November 2022.

After being referred to the study site and undergoing a review of eligibility criteria, potential participants participated in an informed consent process performed by a public health doctor from Haiphong University of Medicine and Pharmacy (HPUMP). Once enrolled in the study, trained interviewers administered sociodemographic and GBV questionnaires. Each in-person interview lasted approximately 90 min, and participants received $6 (150,000 VND) as compensation for their time.

Measurements

The World Health Organization (WHO) – Multi-Country Study on Violence Against Women survey instrument was adapted based on focus group discussion with the FSWs and CBOs in Haiphong to specifically measure GBV against FSWs. This tool has previously been utilised in two national surveys conducted in 2010 and 2019 to assess GBV against the general adult female population in Viet Nam (MOLISA, GSO and UNFPA, Citation2020). Four types of violence were assessed including sexual violence (SV), physical violence (PV), emotional violence (EV) and economic violence (EcV). In addition, data were gathered on the relationship between FSWs and the perpetrators: male clients, male intimate partners, and others (police, family members, pimps, others sex workers).

For male client and male intimate partner perpetrators, four types of GBV were assessed. The PV measurement included six items: (a) slapping her or throwing something at her that could hurt her; (b) pushing, shoving or pulling her hair; (c) hitting her with a fist or an object that could hurt her; (d) kicking, dragging or beating her up; (e) choking or purposefully burning her; (f) threatening or using a gun, knife or other weapon against her. The SV measurement had three items: (a) being forced to have sexual intercourse when she did not want to; (b) had sexual intercourse when she did not want to because she was afraid of what her partner might do; (c) being forced to do something sexual that she found degrading or humiliating. The EV measurement had four items: (a) insulting her or making her feel bad about herself; (b) belittled or humiliated her in front of other people; (c) intentionally scaring or intimidating her; (d) threatening to hurt her or someone she cared about. The EcV measurement had five items: (a) prohibiting her from getting a job, going to work, trading, earning money or participating in income generation projects; (b) taking her earnings from her against her will; (c) refusing to give her money needed for household expenses even when he had money for other things; (d) expecting her to be financially responsible for his family and himself; (e) requiring her to ask his permission before buying anything for herself; (f) refusing to pay after having sexual intercourse (new items). All four forms of GBV were assessed for clients and intimate partners. For the other perpetrators, only two types of GBV – physical and sexual violence – were assessed. Based on findings from the focus group discussion with the FSWs and CBOs, economic and emotional violence by individuals other than intimate partners and clients might be not consistent depending on whether they were aware of the participant’s engagement in sex work. For other perpetrators, the PV measurement had four items: (a) slapping, hitting, beating, kicking or anything else to hurt her; (b) throwing something at her, pushing her or pulling her hair; (c) choking or purposefully burning her; (d) threatening or using a gun, knife or other weapon against her. The SV measurement had six items: (a) forcing her to have sexual intercourse when she did not want to; (b) engaging in sexual intercourse when she was too drunk or drugged to refuse; (c) coercing or persuading to have sex against her will with multiple men at the same time; (d) attempting to force her into sexual intercourse when she did not want to; (e) touching her sexually against her will; (f) making her touch their private parts against her will. For each reported act of violence, respondents were asked whether it had happened ever in her lifetime (lifetime violence), and, if so, whether it happened in the past 12 months.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) were measured using the ACEs Questionnaire (ACE-Q) (Felitti et al., Citation1998). The questionnaire has 10 items that measure 10 different types of childhood trauma before the age of 18. Five items were personal experiences: physical abuse, verbal abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect. The remaining five items relate to experiences involving other family members: an alcoholic parent, a mother who was a victim of domestic violence, a family member in jail, a family member diagnosed with a mental illness, and the disappearance of a parent through divorce or abandonment. The response options for each item were ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Statistical analyses

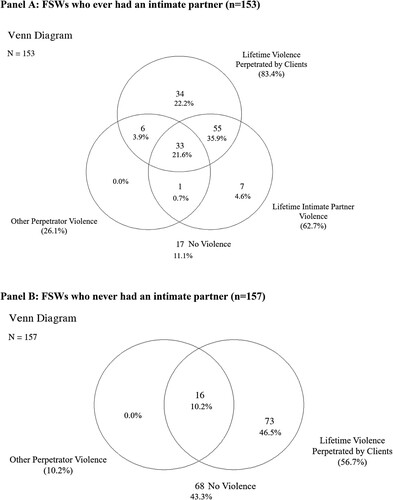

Data were analysed using STATA software (version 15.1, Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). Univariate descriptive statistics and violence prevalences were calculated. Spearman’s correlation was utilised to establish a covariance matrix of continuous measures for IPV, client-perpetrated violence (CPV), other violence, and ACEs. Patterns of poly-victimisation were visualised using a Venn diagram. A probability level of 0.05 or lower was considered statistically significant.

All forms of violence were assessed by the perpetrator category. Items were dichotomised as yes versus no, for each variable showing lifetime or past-year violence by each perpetrator category (client, intimate partner, other perpetrator). Three variables indicating yes or no violence were generated for intimate partners, clients and other perpetrators. Additionally, lifetime violence items were summed for each perpetrator category aimed to show lifetime exposure to different types of violence irrespective of who the perpetrator was.

The ACE-Q was calculated into a score for the total ACEs and for each component including personal trauma and trauma related family member. Within each component group, an FSW was categorised as have been exposed to ACEs if there was at least one ‘yes’ answer. An FSW was classified as having ACEs if there was one component group positive at minimum.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Haiphong University of Medicine and Pharmacy (decision number: 08/IRB-HPMU). The participants underwent a written consent process before interviewing. The participants who reported experiences of violence were informed about violence victim support services and were referred to medical services such as testing for HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and opioid substitution treatment, if needed.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The median age of FSWs in the sample was 33.1 years (IQR 22–44, range 18–76), and 44.8% of them originated from provinces other than Haiphong. The majority of the sample had incomplete schooling with 64.6% having less than a high-school level education, and 10.6% were ethnic minorities. Regarding marital status, most were either single (40.3%) or divorced/separated (40.7%), and nearly half had a current male intimate partner (49.3%). Two hundred fifty-two FSWs self-reported that they had ever been tested for HIV, and only four self-reported that they were HIV seropositive (1.6%). The median duration of sex work employment was five years (IQR 2–10). In terms of the type of sex work, 13.5% self-identified as barmaid/dance hostesses, 45.5% as brothel workers, 9.0% as street-based sex workers, 19.4% as managed/guardian call girls and 20.7% as independent/solo call girls. The median monthly income was $521.70 (IQR 347.8–869.5), which is equivalent to approximately 12.000.000 Vietnamese dongs. Only 9 (2.9%) of FSWs reported being arrested by the police in the past 12 months ().

Table 1. Description of demographic characteristics of female sex workers in Haiphong (n = 310).

Adverse childhood experience, lifetime and prior-year violence, by type of violence and type of perpetrator

In terms of violence perpetrated by clients, the lifetime prevalence was 70.0%, reported across 47.4% for PV, 51.9% for SV, 55.4% for EV and 35.9% for EcV; the overall 12-month prevalence was 61.3%, including 34.8% for PV, 42.6% for SV, 47.1% for EV and 27.4% for EcV. Regarding violence perpetrated by an intimate partner, the lifetime prevalence was 62.1%, with 34.6% for PV, 35.3% for SV, 46.4% for EV and 36.0% for EcV; the 12-month prevalence was 58.2%, reported among 26.1% for PV, 32.7% for SV, 37.2% for EV and 33.3% for EcV. Any physical or sexual violence by other perpetrators in lifetime and in the past year was reported as 18.1% and 14.2%, respectively. Other common perpetrators of physical violence were pimps or managers (63.8%), other FSWs (27.7%), strangers (19.2%) and acquaintances (12.8%). Other common perpetrators of sexual violence were pimps or managers (60.0%), strangers (38.2%) and acquaintances (14.3%). Because the prevalence of any form of violence perpetrated by others was only 18.1%, we regrouped this prevalence estimate while presenting the overlaps of poly-victimisation in the Venn diagram.

Sixty-five percent of FSWs reported experiencing at least one ACE, with 51.2% having experienced personal trauma and 50.0% having experienced trauma related to family members. The mean ACE-Q score was 2.3 (IQR 0–4) ().

Table 2. Pattern of victimisation among female sex worker in Hai Phong.

Poly-victimisation among FSWs

The percentage of FSWs who experienced violence by at least one perpetrator category was 72.6% in their lifetime and 65.8% in the prior 12 months. Thirty-three individuals (10.6%) reported experiencing violence by three perpetrator categories in their lifetime and 28 individuals (9.0%) reported violence by three perpetrator categories in the prior 12 months ().

Table 3. Polyvictimisation by perpetrator category among the FSWs in Haiphong, Vietnam.

Poly-victimisation among FSWs with a current intimate partner in Haiphong is shown in Panel A, . Only 17 (11.1%) currently partnered FSWs reported experiencing no violence, while 33 (21.6%) reported experiencing all three forms of GBV throughout their lifetime. The greatest overlap was observed between IPV and CPV, with 55 FSWs (35.9%) experiencing both.

Figure 1. Poly-victimisation among FSWs in Haiphong: Perpetrator-specific type of violence in adulthood (intimate partner, client, other perpetrator).

Poly-victimisation of FSWs who never had an intimate partner in Haiphong is shown in Panel B, . Sixty-eight (43.3%) never-partnered FSWs experienced no violence, while 16 (10.2%) experienced two forms of GBV in their lifetime, and 73 FSWs (46.5%) who experienced violence only by a client. There were significant correlations between CPV, IPV, violence by other perpetrators, and ACEs, with pairwise Spearman’s rho values ranging from 0.31 to 0.39 (p < 0.001) ().

Table 4. Spearman rank correlations (rho) between lifetime violence experiences by a client, intimate partner, other perpetrator, and Adverse Childhood Experiences, FSWs in Haiphong, Vietnam.

FSWs who engaged in illicit drug use in the past 6 months, had a history of drug/alcohol use before having sex with a client, and reported infrequent condom use before having sex with a client experienced notably higher levels of violence compared to other FSWs (p < 0.05) (Supplementary data). Furthermore, nearly 80% of FSWs (163 individuals) did not seek help from anyone after experiencing violence (Supplementary data).

Discussion

Our findings underscore the disproportionate vulnerability of FSWs in Haiphong, Viet Nam, to violence by multiple categories of perpetrators across their lifetime and within the past year. Most studies in Viet Nam on violence against FSWs have been qualitative, with small sample sizes (Huber et al., Citation2019; Rushing et al., Citation2005). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first quantitative examination of all types of violence against FSWs in Haiphong. Findings showed that violence by a clients was the most common form reported by women in the sample (70.0% during life and 61.3% in the prior year), regardless of whether or not the FSW had an intimate partner. Among the FSWs with a current intimate partner, the prevalence of IPV was 61.3% during lifetime and 58.2% in the past year. Compared with the general population in the National Study on Violence Against Women (n = 5553), the lifetime prevalence of any violence was similar (61.3% versus 62.9%), but the prevalence of violence in the past 12 months was notably higher among FSWs (58.2% versus 31.6%). Emotional violence accounted for the highest percentage of all types of violence perpetrated by an intimate partner throughout life (46.4% in FSWs and 47.0% in the general population) (MOLISA, GSO and UNFPA, Citation2020). In addition, our findings revealed experiences of violence perpetrated by others, such as pimps/managers, acquaintances, strangers and even other FSWs, due to the competitive nature of their work. Traumatic childhood experiences were also a notable feature of our study, with over half of the participants reporting at least one such experience. This result is unsurprising considering a recent survey in Viet Nam using the ACE-Q highlighted that 74% of high school students reported having at least one lifetime ACE (Le et al., Citation2022). However, it is worth noting that FSWs in our study did not report police-perpetrated violence, which has been shown to be quite common in several studies (Footer et al., Citation2019; McBride et al., Citation2020; Peitzmeier et al., Citation2021). We hypothesise that the absence of reporting this type of violence may be influenced by the composition of our sample (primary establishment-based sex workers) and the low arrest rate in the past 12 months.

Poly-victimisation occurred in the majority of our sample. Among FSWs who currently had intimate partners, we found that 88.9% experienced at least one form of victimisation during their lifetime, and nearly a quarter experienced all four types of victimisation from male intimate partners, male clients and other perpetrators. Among the non-intimate partner FSWs, 56.7% experienced one of two types of violence from clients and other perpetrators. The most common overlaps in violence occurred between clients and intimate partners. A previous study also indicated that child sexual assaults were higher in SW (Vaddiparti et al., Citation2006). These findings highlight that engaging in sex work elevates women’s vulnerability to violence in adulthood and exposes the inequalities that FSWs face in the contexts when sex work is illegal and socially stigmatised (Huber et al., Citation2019; Nguyen et al., Citation2016; Rushing et al., Citation2005).

The overlaps of violence observed in our study are notably higher compared to the reported levels of violence in other studies of violence among FSWs (Coetzee et al., Citation2017). However, this finding is predictable given the high coverage of various types of violence experienced by perpetrators in our questionnaire, ranging from relatives, strangers to pimps/manager. These perpetrator types are often underreported in other studies on violence among FSWs. A pairwise correlation analysis revealed significantly positive associations between different forms of violence. In addition, our findings highlighted the notable experiences of violence among the FSWs who did not use condoms regularly, who used drugs/alcohol before having sex with the clients, and who used illicit drugs in the past six months (supplementary data). Although our research cannot elaborate on causal sequencing of all types of violence, other studies have demonstrated that violence continues unabated into adulthood in two-thirds of FSWs who experienced rape during childhood and for over three-quarters of FSWs who had lifetime exposure to other forms of violence (Wechsberg et al., Citation2005). These findings demonstrate the importance of understanding poly-victimisation among FSWs in Haiphong, where we have shown a higher overall prevalence of violence than previously documented.

Based on the findings of two national violence studies, Viet Nam has implemented several strategies to prevent violence against women and children. These strategies include expanding HIV prevention services for sex workers, setting up centres to protect women's and children's health, building shelters for victims of violence, and providing hotlines in emergencies (Diane et al., Citation2010). While these guidelines strongly encourage for comprehensive services to address GBV, it appears that the available services are not effectively reaching FSWs. Specifically, our study showed that 163/204 FSWs (79.9%) who experienced violence within the prior 12 months did not seek help from anyone (Supplementary data). Therefore, GBV interventions for FSWs are needed in this setting and should span different levels, from individual (violence screening and response services), community (violence-related safety promotion and risk reduction counselling within HIV risk reduction programming) and multisectoral (empowerment, advocacy, and crisis response with reductions in violence) interventions (Decker et al., Citation2022; Gilbert et al., Citation2015).

Our study had several limitations. Violence perpetrated by individuals other than clients and intimate partners may have been underreported due to the order in the questionnaire (which asked after the client and intimate partner experiences), especially by pimps or brothel managers, who tended to control the timing and movements of FSWs during our survey. This format could have resulted in participants feeling emotionally overwhelmed and unable to fully disclose further violence exposure, as the managed/guardian call girl had notably higher exposure to violence than the other types of sex works (supplementary data). Additionally, our measure of IPV only concerned current intimate partners and did not capture experiences of IPV from former partners. We also did not assess emotional and economic violence perpetrated by individuals other than client and intimate partners. Furthermore, ACEs before 18 years, as highlighted above, might have been underreported due to recall bias. FSWs who self-identified as queer were not considered comprehensively in this study, so violence from female clients or female intimate partners was not assessed. Therefore, our findings may reflect a lower estimate of violence prevalence in this population. Further research on violence among FSWs who hold other marginalised identities, such as gender and sexual minorities, is an important avenue for future research in Viet Nam. Future research should aim to understand perpetrator-specific patterns of violence and the associated factors to ensure that FSW programme implementers can address areas of concern. Finally, self-reported HIV status in our study might not be entirely accurate and survey-administered HIV testing could be considered in future research to gain insights into the impact of violence on the well-being and normalisation of FSW’s life.

Conclusions and recommendations

In Haiphong, FSWs are exposed to high rates of multiple types of violence across their lifetime and within the prior 12 months. Adverse childhood experiences, current substance use, and lack of condom use before having sex with the client might be contributing factors to the poly-victimisation experienced by the FSWs. Therefore, an urgent need exists for a research programme aimed at examining strategies to reduce and to prevent violence against FSWs from different perpetrators. This programme should also focus on clearly defining and implementing appropriate and inclusive violence risk reduction interventions for sex workers, such as healing intervention, mental health interventions and multi-level integrated interventions which target salient mechanisms of the substance abuse, violence and AIDS syndemic. This work requires collective attention by policy makers, programme implementers, authorities, researchers and community members.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Author contributions

Study conception: HTG, PMK. Protocol preparation: HTG, PMK, CES, DPE, SSM, KY. Data collection: HTG, PMK. Data analysis: HTG. Accessed and verified the underlying data: PMK. Drafting of the manuscript: HTG; Editing the manuscript: PMK, CES, DPE, SSM, KY. All authors significantly contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.4 KB)Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a D43 training grant from the Fogarty International Center to Emory University (5D43TW012188 PI Yount MPI Giang). The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The full data set is available upon request to the authors at Hai Phong University of Medicine and Pharmacy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnard, M., Hart, G., & Church, S. (n.d.). Client violence against prostitute women working from street and off-street locations: A three city comparison. ESRC- Economic & Social Reserch Council.

- Beattie, T. S. H., Bhattacharjee, P., Ramesh, B. M., Gurnani, V., Anthony, J., Isac, S., Mohan, H. L., Ramakrishnan, A., Wheeler, T., Bradley, J., Blanchard, J. F., & Moses, S. (2010). Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: Impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 476. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-476

- Becker, M. L., Bhattacharjee, P., Blanchard, J. F., Cheuk, E., Isac, S., Musyoki, H. K., Gichangi, P., Aral, S., Pickles, M., Sandstrom, P., Ma, H., Mishra, S. & Team on behalf of the T. S. (2018). Vulnerabilities at first Sex and their association with lifetime gender-based violence and HIV prevalence among adolescent girls and young women engaged in sex work, transactional sex, and casual sex in Kenya. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79(3), 296. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001826

- Coetzee, J., Gray, G. E., & Jewkes, R. (2017). Prevalence and patterns of victimization and polyvictimization among female sex workers in Soweto, a South African township: A cross-sectional, respondent-driven sampling study. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1403815. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1403815

- Decker, M., Rouhani, S., Park, J. N., Galai, N., Footer, K., White, R., Allen, S., & Sherman, S. (2021). Incidence and predictors of violence from clients, intimate partners and police in a prospective US-based cohort of women in sex work. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 78(3), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-106487

- Decker, M. R., Lyons, C., Billong, S. C., Njindam, I. M., Grosso, A., Nunez, G. T., Tumasang, F., LeBreton, M., Tamoufe, U., & Baral, S. (2016). Gender-based violence against female sex workers in Cameroon: Prevalence and associations with sexual HIV risk and access to health services and justice. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 92(8), 599–604. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052463

- Decker, M. R., Lyons, C., Guan, K., Mosenge, V., Fouda, G., Levitt, D., Abelson, A., Nunez, G. T., Njindam, I. M., Kurani, S., & Baral, S. (2022). A systematic review of gender-based violence prevention and response interventions for HIV key populations: Female sex workers, men who have sex with men, and people who inject drugs. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(2), 676–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211029405

- Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y. T., García-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., Lim, S., Bacchus, L. J., Engell, R. E., Rosenfeld, L., Pallitto, C., Vos, T., Abrahams, N., & Watts, C. H. (2013). Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science (New York, N.Y.), 340(6140), 1527–1528. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240937

- Diane, G., Vu, S. H., Kathy, T., & Khamsavath, C. (2010). Gender-Based Violence in Viet Nam: Issue paper. UN Women – Asia-Pacific. https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/05/gender-based-violence-issue-paper

- Eileen, S., Le, T. T., Tran, V. D., Le, T. V. A., Nguyen, V. T., & Nguyen, X. H. (2017). Access to criminal justice by women subject to violence in Viet Nam—Women’s justice perception study. https://vietnam.un.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Research%20Report%200905.pdf

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S., & Kracke, K. (2009). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey. In: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

- Footer, K. H. A., Park, J. N., Allen, S. T., Decker, M. R., Silberzahn, B. E., Huettner, S., Galai, N., & Sherman, S. G. (2019). Police-related correlates of client-perpetrated violence among female sex workers in Baltimore City, Maryland. American Journal of Public Health, 109(2), 289–295. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304809

- García-Moreno, C., Pallitto, C., Devries, K., Stöckl, H., Watts, C., & Abrahams, N. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization.

- Garcia-Moreno, C., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., Watts, C. H., & WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. (2006). Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet (London, England), 368(9543), 1260–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8

- Gilbert, L., Raj, A., Hien, D., Stockman, J., Terlikbayeva, A., & Wyatt, G. (2015). Targeting the SAVA (substance abuse, violence and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: A global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 69(02), S118–S127. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000626

- Hail-Jares, K., Chang, R. C. F., Choi, S., Zheng, H., He, N., & Huang, Z. J. (2015). Intimate-partner and client-initiated violence among female street-based sex workers in China: Does a support network help? PLoS One, 10(9), e0139161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139161

- Huber, J., Ferris France, N., Nguyen, V. A., Nguyen, H. H., Thi Hai Oanh, K., & Byrne, E. (2019). Exploring beliefs and experiences underlying self-stigma among sex workers in Hanoi, Vietnam. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(12), 1425–1438. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1566572

- Jafari, M. J., Saghi, F., Alizadeh, E., & Zayeri, F. (2019). Relationship between risk perception and occupational accidents: A study among foundry workers. The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 94(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42506-019-0025-6

- Jewkes, R., Milovanovic, M., Otwombe, K., Chirwa, E., Hlongwane, K., Hill, N., Mbowane, V., Matuludi, M., Hopkins, K., Gray, G., & Coetzee, J. (2021). Intersections of sex work, mental Ill-health, IPV and other violence experienced by female sex workers: Findings from a cross-sectional community-centric national study in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), Article 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211971

- Johnston, L. G., Sabin, K., Hien, M. T., & Huong, P. T. (2006). Assessment of respondent driven sampling for recruiting female sex workers in two Vietnamese cities: Reaching the unseen sex worker. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 83(Suppl 1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9099-5

- Katsulis, Y., Lopez, V., Durfee, A., & Robillard, A. (2010). Female sex workers and the social context of workplace violence in Tijuana, Mexico. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 24(3), 344–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01108.x

- Kerrigan, D., Karver, T. S., Barrington, C., Davis, W., Donastorg, Y., Perez, M., Gomez, H., Mbwambo, J., Likindikoki, S., Shembilu, C., Mantsios, A., Beckham, S. W., Galai, N., & Chan, K. S. (2021). Development of the experiences of sex work stigma scale using item response theory: Implications for research on the social determinants of HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 25(2), 175–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03211-1

- Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0

- Le, T., Dang, H.-M., & Weiss, B. (2022). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences among Vietnamese high school students. Child Abuse & Neglect, 128, 105628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105628

- Le, T. T., Nguyen, Q. C., Tran, H. T., Schwandt, M., & Lim, H. J. (2016). Correlates of HIV infection among street-based and venue-based sex workers in Vietnam. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 27(12), 1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462415608556

- Leis, M., McDermott, M., Koziarz, A., Szadkowski, L., Kariri, A., Beattie, T. S., Kaul, R., & Kimani, J. (2021). Intimate partner and client-perpetrated violence are associated with reduced HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake, depression and generalized anxiety in a cross-sectional study of female sex workers from Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(Suppl 2), e25711. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25711

- Maclin, B. J., Wang, Y., Rodriguez-Diaz, C., Donastorg, Y., Perez, M., Gomez, H., Barrington, C., & Kerrigan, D. (2023). Comparing typologies of violence exposure and associations with syndemic health outcomes among cisgender and transgender female sex workers living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. PLoS One, 18(9), e0291314. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291314

- McBride, B., Shannon, K., Bingham, B., Braschel, M., Strathdee, S., & Goldenberg, S. M. (2020). Underreporting of violence to police among women sex workers in Canada. Health and Human Rights, 22(2), 257–270.

- MOLISA, GSO and UNFPA. (2020, July 14). National study on violence against women in Viet Nam (2019). UNFPA Asiapacific. https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/national-study-violence-against-women-viet-nam-2019-0

- Ngo, A. D., McCurdy, S. A., Ross, M. W., Markham, C., Ratliff, E. A., & Pham, H. T. B. (2007). The lives of female sex workers in Vietnam: Findings from a qualitative study. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9(6), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050701380018

- Nguyen, T. T. H., Duong, T. C., Doan, T. T., & Nguyen, T. T. (2016). HIV prevalence and coverage of HIV prevention services among female sex workers in Hai Phong in 2012. Vietnamese Journal of Preventive Medicine, 16(9), 31–39.

- Nguyen, T. V., Khuu, N. V., Truong, P. H., Nguyen, A. P., Truong, L. X. T., & Detels, R. (2009). Correlation between HIV and sexual behavior, drug use, trichomoniasis and candidiasis among female sex workers in a Mekong Delta Province of Vietnam. AIDS and Behavior, 13(5), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9499-5

- Panchanadeswaran, S., Johnson, S. C., Sivaram, S., Srikrishnan, A. K., Latkin, C., Bentley, M. E., Solomon, S., Go, V. F., & Celentano, D. (2008). Intimate partner violence is as important as client violence in increasing street-based female sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV in India. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 19(2), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.013

- Peitzmeier, S. M., Wirtz, A. L., Beyrer, C., Peryshkina, A., Sherman, S. G., Colantuoni, E., & Decker, M. R. (2021). Polyvictimization among Russian sex workers: Intimate partner, police, and pimp violence cluster with client violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15-16), NP8056–NP8081. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519839431

- Penfold, C., Hunter, G., Campbell, R., & Barham, L. (2005). Tackling client violence in female street prostitution: Inter-agency working between outreach agencies and the police. Policing & Society, 14(4), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1043946042000286074

- PERFAR. (2020). Vietnam country operational plan (COP/ROP) 2020 strategic direction summary. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COP-2020-Vietnam-SDS-Final-.pdf

- Roberts, S. T., Flaherty, B. P., Deya, R., Masese, L., Ngina, J., McClelland, R. S., Simoni, J., & Graham, S. M. (2018). Patterns of gender-based violence and associations with mental health and HIV risk behavior among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya: A latent class analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 22(10), 3273–3286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2107-4

- Rosenthal, D., & Oanha, T. T. K. (2006). Listening to female sex workers in Vietnam: Influences on safe-sex practices with clients and partners. Sexual Health, 3(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH05040

- Rushing, R., Watts, C., & Rushing, S. (2005). Living the reality of forced sex work: Perspectives from young migrant women sex workers in northern Vietnam. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 50(4), e41–e44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.03.008

- Semple, S. J., Stockman, J. K., Pitpitan, E. V., Strathdee, S. A., Chavarin, C. V., Mendoza, D. V., Aarons, G. A., & Patterson, T. L. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of client-perpetrated violence against female sex workers in 13 Mexican Cities. PLoS One, 10(11), e0143317. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143317

- Shahmanesh, M., Wayal, S., Cowan, F., Mabey, D., Copas, A., & Patel, V. (2009). Suicidal behavior among female sex workers in Goa, India: The silent epidemic. American Journal of Public Health, 99(7), 1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149930

- Ulibarri, M. D., Salazar, M., Syvertsen, J. L., Bazzi, A. R., Rangel, M. G., Orozco, H. S., & Strathdee, S. A. (2019). Intimate partner violence among female sex workers and their noncommercial male partners in Mexico: A mixed-methods study. Violence Against Women, 25(5), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218794302

- UNAIDS. (2022). United States Strategy to prevent and respond to gender-based violence globally. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/GBV-Global-Strategy-Report_v6-Accessible-1292022.pdf

- Vaddiparti, K., Bogetto, J., Callahan, C., Abdallah, A. B., Spitznagel, E. L., & Cottler, L. B. (2006). The effects of childhood trauma on sex trading in substance using women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(4), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9044-4

- Vos, T., Barber, R. M., Bell, B., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Biryukov, S., Bolliger, I., Charlson, F., Davis, A., Degenhardt, L., Dicker, D., Duan, L., Erskine, H., Feigin, V. L., Ferrari, A. J., Fitzmaurice, C., Fleming, T., Graetz, N., Guinovart, C., Haagsma, J., … Murray, C. J. (2015). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. The Lancet, 386(9995), 743–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

- Wechsberg, W. M., Luseno, W. K., & Lam, W. K. (2005). Violence against substance-abusing South African sex workers: Intersection with culture and HIV risk. AIDS Care, 17(Suppl 1), S55–S64. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120500120419