ABSTRACT

Nearly 31% of the Ghanaian population are adolescents, and these populations persistently face high rates of teenage pregnancies and unsafe abortions. This is despite sexual and reproductive health (SRH) being taught in the school curriculum. In this qualitative study, we explore the factors affecting adolescents’ access to, and experiences of, SRH services in Accra, Ghana. We conducted 12 focus group discussions (FGDs) with adolescents and 13 key informant interviews (KIs) in Ghana. The FGDs were conducted with school-going and out-of-school adolescents. KIIs were conducted with various stakeholders working with adolescents or in SRH services. All interviews were conducted in English, audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. We applied the Dahlgren-Whitehead Rainbow model of health determinants and used a thematic analysis. Eight themes were identified, across micro, meso and macro levels, that influence adolescents’ SRH access and experience in Accra. These included: family, social networks, the role of schools, health providers and services, the policy landscape, gender norms, cultural norms, and poverty. The findings highlight several factors that influence adolescents’ access to appropriate SRH services in this context and demonstrate the need for a multisectoral effort to address structural factors such as harmful gender norms and persistent poverty.

Introduction

Adolescence (10–19 years) is a period with significant physical and psychological changes, while ‘late adolescence’ includes individuals up to age 24 years (WHO, Citation2015). Globally there are 1.8 billion people aged 10-24 years, approximately 90% of whom live in LMICs (Ng’andu et al., Citation2022). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) has been identified as an important public health issue globally (Usonwu et al., Citation2021) but continues to add to the global burden of disease (Muttalib et al., Citation2020). The situation is worrying in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where pregnancy-related complications and HIV are the leading causes of death among adolescents (Fan et al., Citation2016). Approximately six out of seven new HIV infections in SSA occur among adolescents (15-19 years), with older adolescent girls and young women (15-24 years) twice as likely to be living with HIV than older adolescent boys and young men (Murewanhema et al., Citation2022).

Social determinants play a crucial role in ASRH and their impact on adolescents’ SRH outcomes can be nuanced and layered (Challa et al., Citation2018). At the individual level, this may include a lack of information about SRH services and contraception, and negative attitudes towards contraceptive use (Ajayi et al., Citation2018). At the family level, communication about ASRH can send strong messages. Parents delineate the boundaries of acceptable discussion, tending to focus on issues such as puberty and hygiene, upholding religious and sociocultural norms that act as powerful moderators to control and repress adolescent sexuality (Agbeve et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Community-level factors such as a lack of SRH education in schools, lack of adolescent-friendly SRH services, stigma around sex and pressures to adhere to sociocultural norms and behaviours have been described (Maina et al., Citation2020; Denno et al., Citation2015; Melesse et al., Citation2020). At the societal and policy level, important factors include gender inequality, poverty and lack of strategic policy support for improving ASRH services and education in schools (Melesse et al., Citation2020; Moreau et al., Citation2019).

This study took place in Ghana, a country where nearly 31% of the population is aged 10-24 years (UNFPA, Citation2022). Policies for adolescent health, including ASRH, exist in Ghana but face significant implementation challenges. Financial resources are inadequate and overly reliant on external funding, and there is poor coordination of ASRH with other parts of the health system (Agblevor et al., Citation2023). ASRH is being covered in schools as part of Ghana’s Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) syllabus, under the supervision of the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and Ghana Education Services (GES), but faces challenges with inadequate teacher training, resulting in poor implementation and inconsistent messaging (Keogh et al., Citation2021a). Contraceptive knowledge among unmarried adolescents is reported to be high, but Oppong et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated a significant gap between knowledge and use among sexually active unmarried 15–24 year-old females. Misinformation and myths about side effects are implicated in non-use (Amoah et al., Citation2023; Beson et al., Citation2018), as well as cultural and religious beliefs (Ziblim et al., Citation2022). The region also has limited access to contraceptives, with family planning coverage for single adolescent girls at a low rate of 38%, and an estimated 25% of unsafe abortions are among 15 to 19-year-old girls. Furthermore, approximately 16 million girls aged 15-19 years gave birth as of 2019, with 2.5 million of them under the age of 16 (Engelbert et al., Citation2019). Many adolescents have limited knowledge about safe abortion services (Keogh et al., Citation2021b). A study by Engelbert Bain et al. (Citation2020a) found that 13 of the 15 abortions recorded were unsafe among 30 previously pregnant 13-19 year-olds in a slum located in Accra. Adolescents often resort to unsafe practices to abort, such as using misoprostol (sometimes in combination with other medications), inserting herbs into the vagina, or ingesting concoctions (Keogh et al., Citation2021b).

Even though Ghana has implemented a CSE curriculum and a range of ASRH policies, high rates of pregnancy and abortion persist. Our study set out to explore some of the underlying factors that affect adolescents’ knowledge of and access to SRH services in Accra, Ghana.

Conceptual framework

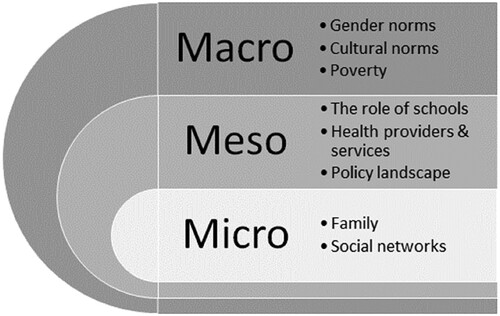

We applied the Dahlgren and Whitehead (Citation1991) rainbow model of health determinants to examine the underlying factors that affect adolescents’ access to, and experience of, SRH services in Ghana. The rainbow model describes distinct levels which can impact broader health outcomes and articulate the strong linkages across and between levels. Socioeconomic and cultural conditions at the macro level (e.g. gender and religious norms and values, policy or funding) determine how people uphold good health outcomes, including SRH, in a population. These macro dynamics filter down, affecting people’s living and working conditions, such as education and access to SRH services, and factors at the social and community (meso) level, where family and community networks intersect with, and drive, individual (micro) factors including lifestyle choices and risk-taking. This socio-economic model provides an understanding of the diverse interventions needed to effect change and can galvanise multisector efforts to action change in areas such as SRH (Dahlgren & Whitehead, Citation2021).

Methods

This exploratory study was conducted in July 2019 with limited resources, so data collection was restricted to Ghana’s Greater Accra Region, specifically to the Adentan Municipal. We used the WHO definition of ‘late adolescence’ to recruit participants aged between 15-24 years. The sample included two groups: adolescents currently in secondary school and out-of-school adolescents. We purposively sampled public and private senior high schools. In-school adolescents were a convenience sample, recruited by the head of the schools. Out-of-school adolescents were recruited by NGOs working with young people working in the markets or along some of the major roads in the area. Many of the adolescents we engaged with would be classified as urban poor; those attending private schools would likely be more affluent, but selection was not based on socioeconomic status. We conducted 12 focus group discussions (FGDs). Four were conducted with only boys, four with only girls, and four were mixed i.e. had both boys and girls. Adolescents participated in only one FGD; FGD numbers ranged from 6-10 participants per group; and a total of 96 adolescents were included (). The FGDs took place in safe premises that guaranteed adolescents’ privacy (e.g. schools or NGO offices). Topic areas explored adolescents’ pathways to SRH information and services, their decision-making processes, and their access to, and experiences of, SRH services, using probes to elicit more detailed responses. The discussion guide had been piloted in advance in an FGD with six adolescents in a secondary school in Accra. The pilot went very well, and no changes were made to the discussion guide.

Table 1. Description of participants of the Focus Group Discussions (n = 96).

Thirteen key informant interviews (KIIs) were also conducted with senior and mid-level professionals involved in the planning and delivery of ASRH services and CSE curricula in schools (). Key informants, from government, education and NGOs, were purposively selected to provide their views on the broader organisational and institutional context and challenges in providing adolescent SRH services in Ghana. KIIs were scheduled in advance and took place in the participant’s place of work.

Table 2. Description of key informants (n = 13).

All interviews and FGDs were conducted in English (Ghana’s official language). FGDs were lively and engaging, with a lot of laughter, as adolescents talked and shared their thoughts and ideas. FGDs were audio-recorded with permission, transcribed verbatim by an accredited transcription service in Ghana, checked for accuracy and imported into NVivo for analysis. The data were analysed thematically using Braun and Clark’s six-phase framework (Braun and Clark, Citation2006). Initial coding was conducted by the first authors with regular discussions with the last author. Final themes and sub-themes were identified after discussions with all authors and were mapped on the conceptual framework.

Ethical approval and considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee for the Humanities (ECH151/18-19), University of Ghana and the Institutional Review Board, City, University of London (ETH1819-0314). Given the sensitive nature of the topic, it was important to safeguard participants’ rights to informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, and their right to refuse to answer some questions or to withdraw from the study at any time. These issues were explained in Participant Information Sheets (PIS). While it was feasible to guarantee full privacy and confidentiality from the research team, it was unrealistic to offer such reassurances on behalf of other participants in the FGDs and participants were made aware of this before giving informed consent. Groups were asked to agree to respect each other’s privacy before discussions began and then reminded again at the end of the FGDs. Further, participants were asked to choose a pseudonym for the duration of the FGDs; these improved anonymity as they were used as the identifiers for data storage and were used in the FGD transcripts and quotes. For adolescents under 18 years, consent forms were signed by both the adolescent and their guardian. Protocols for confidentiality and professionalism were observed throughout.

Results

All adolescents quoted in the results were identified using the pseudonym they chose for the FGD, followed by: their gender (F or M), age, in-school or out-of-school (IS or OOS), employed or unemployed status (E or unE) at the time of data collection, and the type of FGD (only boys = OB, only girls = OG, or mixed = MX);. For example, ‘Tim, M/19/IS/unE-OB’ is Tim, who is male, 19 years old, was in school but not employed at the time of data collection and participated in a boy-only FGD.

To protect participant confidentiality, KIIs were grouped according to the sector (government, education, NGO), but each retains their individual identifier to allow readers to judge the spread of data across participants ().

This study found several themes influencing adolescents’ access to SRH services that operate at micro, meso and macro levels (). These themes may act as barriers or facilitators to knowledge of, and access to, SRH services.

Micro-level factors affecting ASRH

The most prominent factors operating at the micro-level that participants discussed were relationships within family units and social networks.

Family

Most adolescents reported not being comfortable asking their parents and siblings about SRH for fear of being judged. However, some felt able to turn to family, particularly mothers, when they needed help.

And my mum is always available, always in the house and doing things, like things with me or always interacting with me so she is the best person I always talk to. (Bruce, M/20/IS/unE/OB).

Social networks

Social networks, such as friends and religious institutions, were key sources of information for many adolescents. Most adolescents said they felt comfortable discussing SRH information and services with their peers. However, some mentioned they had misgivings as they were aware that friends did not necessarily have sufficient expertise.

They [friends] can influence you wrongly. So I don’t trust them too much. (Risky, F/16/IS/UnE-MX)

Sometimes they [church community] teach us the side effects of sex; the infections you can get from it. They advise us, and even tell us to wait till after 20 years before we have sex because we are too young for that. (Joel, M/18/OOS/UnE-OB).

Meso-level factors affecting ASRH

At the meso-level, the role of schools, health services and policy implementation played a significant role in adolescents’ knowledge of, and access to, SRH.

The role of schools

The FGDs demonstrated that the majority of SRH information came via formal channels. Although adolescents in schools indicated they had come across SRH in the CSE syllabus, they expressed reservations about its quality. They thought many teachers lacked the relevant expertise to teach it and would often ‘beat around the bush’ (Blaze, M/17/IS/UnE-OB) with SRH topics.

Key informants agreed and wanted to ensure a better spread of SRH information.

And even, some of the teachers are also not comfortable talking about sex and sex-related issues so that’s another area that eventually if we’re institutionalizing this and rolling it out, we must be thinking about those who are going to administer this intervention at the school level. (KI08, NGO).

The government sends some educationalists to educate us on sexual reproductive health and on how to stay away from STDS. (Ohemaa, F/17/IS/UnE-OG).

We want to use the human-centred design approach linking services to the aspiration of young people and making sure that young people do not just see the SRH service as a need but also a tool to help them achieve their aspirations. So going beyond just talking about the health benefits of let’s say just preventing pregnancy, or treating infections, or how you are even going to practice abstinence. (KI01, Government).

Health providers and services

Some adolescents reported that when they do seek SRH services and support, they are often turned away by health providers or deterred from accessing services due to the attitudes these health providers display. Adolescents described health providers’ attitudes as disrespectful, judgemental and discriminatory. Others outlined situations where healthcare providers were not welcoming and called adolescents ‘bad’ or ‘shameful’ if they were pregnant or trying to obtain contraception. This negative association may also affect wider culture and how SRH services are perceived:

The cultural perception concerning access to SRH services. I would want to see that one changed. Because most of our barriers have the roots in our perceptions as a people. (KI01, Government).

They [SRH service providers] don’t go into details. So, you have to take your phone or someone’s phone and do your research to know more. (Rod, M/17/IS/UnE-MX).

There are six Young and Wise centres in terms of facilities, we have about eight facilities, we have family health clinic which is here, it offers general, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights services, abortion and all of that. (KI01, Government).

Policy landscape

Although Ghana has an ASRH policy, key informants raised concerns about its implementation. Some regions, particularly the Eastern region, lacked sufficient SRH services and programmes. However, the ASRH services engage ‘influential’ people to support the delivery of youth-friendly services:

And we do that [deliver youth-friendly services] by engaging influential people at the community level, regional level and at the national level so with members of parliament and all that. (KI08, NGO).

When we go into that partnership, we build their capacity through training around the core component of the work we do so that that becomes part of what they do at the community level when they do the community level and engagement. (KI08, NGO).

Macro-level factors affecting ASRH

Important factors at the macro level were the impact of gender norms, cultural norms, and religion.

Gender norms

Adolescents described how gender roles impacted the way they navigated SRH issues. These issues were discussed in the single-gender FGDs (and were not brought up in the mixed FGDs). Many girls felt that talking about or seeking SRH services made them look ‘unladylike’ or that conversations about sexual health were not always inclusive of their experiences. Gender differences were also commented upon by a key informant who felt that SRH rights were not the same for men and women in Ghana.

Our traditions do not talk about equal rights, the male factors all the time are right more than the females and the children. (KI02, Education)

There is not much in the curriculum about gender roles, we might touch on the fringes but it’s not something we delve into, but that would depend on the discretion of the teacher. (KI03, Education).

Cultural norms

Adolescents of both genders reported reluctance in accessing SRH services because of stigma; however, the girls tended to experience a higher degree of stigma. Participants commented that girls who wanted to obtain contraceptives were tagged as scandalous individuals as there was the assumption that they were ‘sleeping around’. Some girls articulated their fears that if they did seek services, health providers or members of the community would inform their parents which could get them in trouble. In some cases, services such as safe abortions were not provided to adolescent girls due to stigma.

She [adolescent girl] may be agitated as to whether to come or not and because of the society, the stigma, they are always scared of what people will say so they hold back most at times. (KI06, NGO).

Poverty

Both adolescents and key informants described financial difficulties acting as a barrier to adolescents seeking SRH services. This was a bigger issue for out-of-school adolescents as they were from relatively poorer households. The KIIs commented on ASRH services being underfunded and therefore unable to provide free services to adolescents.

If it comes to condoms, we can give them free of charge, but if we have to insert an implant or an IUD you have to pay and sometimes you don’t have the means to do that. And so, there is that financial barrier. (KI01, Government)

So, if for instance if am above 18, I need my own money, instead of going to my parents – it [affording SRH services] will be very difficult. (Character, M/17/IS/UnE-OB)

Discussion

Despite having a range of ASRH policies, including CSE at schools, Ghana has high rates of teenage pregnancies and abortions. Using FGDs with adolescents in Accra and interviews with key informants, we explored some of the underlying factors affecting adolescents’ knowledge of, and access to SRH services. We identified factors operating at micro, meso and macro levels that inhibit the implementation and impact of ASRH policies.

One of the more significant barriers is that in Ghanaian society, talking about sex is often frowned upon making it extremely difficult for adolescents to openly discuss SRH issues with parents or other members of the community. As a result, adolescents feel hesitant to seek advice or procure contraception, which can increase the risk of unprotected sex, STIs, unintended pregnancies and abortions. A study in Bolgatanga, Ghana by Krugu et al. (Citation2017) found that adolescent girls and young women never discussed issues related to sexual health and relationships with their elders, which also highlights the influence of gender norms on SRH.

School settings may offer a safe environment to have open discussions about relationships, sex and SRH. However, adolescents in Ghana judged the sex education provision in school as inadequate and, as Krugu et al. (Citation2017) found, it often focused on only abstinence. Evidence from other studies found that adolescents who have access to CSE lessen their risk of unplanned pregnancies compared to adolescents who receive abstinence-only or no sex education at all (Kohler et al., Citation2008; Engelbert Bain et al., Citation2020b). CSE is also associated with decreased rates of sexual assault, especially among adolescent girls (Engelbert Bain et al., Citation2020b). Action is needed to build the capacities of teachers to deliver CSE in a non-judgemental manner and to encourage open discussion around relationships, sex and SRH. One study showed that a three-month project started by the Association for Reproductive and Family Health found significant changes in SRH knowledge, contraceptive usage and awareness as a result of SRH interventions held in Ghana that included sex education (Aninanya et al., Citation2015). CSE can also provide information about SRH services and how adolescents can access them, which will equip adolescents with accurate information and allow them to be more confident in their decision-making skills surrounding SRH. Melesse et al. (Citation2020) found that awareness about the availability of SRH services improves adolescents’ use of these services. A UNESCO review indicated that more than 30% of sex education programmes increased condom and contraceptive use (Owusa et al., Citation2011). However, studies have shown that other organisations, especially those working with out-of-school adolescents also need to be involved in providing SRH information, as these adolescents are more likely to face higher rates of unplanned pregnancies (Oppong et al., Citation2021).

Adolescent-friendly services that are non-judgemental and affordable are essential for improving the SRH of adolescents. Awusabo-Asare and Annim (Citation2008) found that two in three adolescent girls and four in five adolescent boys with STI symptoms did not seek health care, and approximately half of single sexually active female adolescents and over a third of single sexually active male adolescents did not use contraceptives. Kumi-Kyereme et al. (Citation2014) found that healthcare providers who were judgemental towards adolescents led to barriers to accessing SRH care and resources for young people. Therefore, it is not only important to provide SRH services but equally important to train health staff. This aligns with Ghana’s Adolescent Reproductive Health Policy (2000) and the National HIV/AIDS and STIs Policy (2001) (Kalembo et al., Citation2013) and with the WHO recommendation for Youth Friendly Health Services (YFHS) that promote ASRH that are equitable, appropriate, effective and accessible (Ahinkora et al., Citation2020).

Further, we found factors at all levels – community, school, health systems, and policy impact adolescents’ awareness of, and access to, ASRH information and services. This requires a multisectoral collaboration that not only operates at the school, health systems and policy levels but also needs to address the underlying systemic issues related to stigma about sex, gender inequality and poverty (Ambresin et al., Citation2013). Denno et al. (Citation2015) suggest that some of these can be addressed by engaging community leaders and parents in adolescent health programmes.

This study found that in order to effectively address the SRH well-being of adolescents in Accra, a multisectoral initiative with strong leadership in schools and health services and buy-in from the community is needed. The Ministry of Education and Ghana Education Service should integrate reproductive health information into the secondary school curriculum and regularly assess it in order to provide adolescents with accurate and sufficient knowledge and empower them when confronted with stigmatised beliefs surrounding sexual health. Similarly, Ghana Health Services needs to ensure SRH services are adolescent-friendly – non-judgemental and easily accessible.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This was a small exploratory study conducted in Greater Accra, a large urban city. Although people from different backgrounds and regions reside in Accra, and we included school-going and out-of-school adolescents to ensure we captured the voices of adolescents from different socio-economic circumstances, our findings apply to Accra and may not be representative of other regions or rural areas of Ghana. Further, to understand how individual factors interact and intersect with community and wider systems factors, it is important to interview parents, community members and leaders. Future research should consider involving a wider set of respondents and including adolescents from other regions, rural areas and from different socio-economic backgrounds.

Conclusion

This study revealed several factors restricting adolescents’ access to SRH information and services that operate at micro, meso and macro levels. We found that although Ghana has CSE in schools and SRH services are available, implementation is poor. To address the SRH needs of adolescents, a multisectoral effort is needed that addresses wider society’s views on sex and sexually active adolescents, as well as gender and cultural norms that affect the experience and quality of CSE teaching and attitudes of health staff providing SRH services. Further, poorly implemented and underfunded policies can also affect the quality of training and resources available to implement these policies. Many adolescents seek information online, therefore providing correct information and services online could be another way to ensure adolescents have easy access to information.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to adolescents and other respondents who provided their valuable time to speak to us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2024.2378495)

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agbeve, A. S., Fiaveh, D. Y., & Anto-Ocrah, M. (2022a). Parent-adolescent sexuality communication in the african context: A scoping review of the literature. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 10(4), 554–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2022.04.001

- Agbeve, A. S., Fiaveh, D. Y., & Anto-Ocrah, M. (2022b). A Qualitative assessment of adolescent-parent sex talk in Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 26(12), 146–160.

- Agblevor, E. A., Darko, N., Prempeh, P., Addom, S., Mirzoev, T., & Agyepong, I. A. (2023). “We have nice policies but … ”: Implementation gaps in the Ghana adolescent health service policy and strategy (2016–2020). Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1198150. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1198150

- Ahinkorah, B. O., Hagan, J. E. Jr, Seidu, A. A., Sambah, F., Adoboi, F., Schack, T., & Budu, E. (2020). Female adolescents’ reproductive health decision-making capacity and contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: What does the future hold? PLoS One, 10(7), 15.

- Ajayi, A. I., Nwokocha, E. E., & Akpan, W. (2018). “It’s sweet without condom”: Understanding risky sexual behaviour among nigerian female university students. Online Journal of Health and Allied Sciences, 16(4), 9. https://www.ojhas.org/issue64/2017-4-9.html.

- Ambresin, A.-E., Bennett, K., Patton, G. C., Sanci, L. A., & Sawyer, S. M. (2013). Assessment of youth-friendly health care: A systematic review of indicators drawn from young people’s perspectives. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(6), 670–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.014

- Amoah, E. J., Hinneh, T., & Aklie, R. (2023). Determinants and prevalence of modern contraceptive use among sexually active female youth in the Berekum East Municipality, Ghana. PLoS One, 18(6), e0286585. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286585

- Aninanya, G. A., Debpuur, C. Y., Awine, T., Williams, J. E., Hodgson, A., & Howard, N. (2015). Effects of an adolescent sexual and reproductive health intervention on health service usage by young people in northern Ghana: A community-randomised trial. PLoS One, 10(4), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125267

- Awusabo-Asare, K., & Annim, S. K. (2008). Wealth status and risky sexual behaviour in Ghana and Kenya. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 6(1), 27–39. Epub 2008/09/09. 613 [pii]. https://doi.org/10.2165/00148365-200806010-00003

- Beson, P., Appiah, R., & Adomah-Afari, A. (2018). Modern contraceptive use among reproductive-aged women in Ghana: prevalence, predictors, and policy implications. BMC Women's Health, 18, 1–8.

- Braun, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Challa, S., Manu, A., Morhe, E., Dalton, V. K., Loll, D., Dozier, J., Zochowski, M. K., Boakye, A., Adanu, R., & Hall, K. S. (2018). Multiple levels of social influence on adolescent sexual and reproductive health decision-making and behaviors in Ghana. Women & Health, 58(4), 434–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1306607

- Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Institute for Futures Studies.

- Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (2021). The Dahlgren-Whitehead model of health determinants: 30 years on and still chasing rainbows. Public Health, 199, 20–24.

- Denno, D. M., Hoopes, A. J., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2015). Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012

- Engelbert Bain, L., Amoakoh-Coleman, M., Tiendrebeogo, K. S. T., Zweekhorst, M. B., De Cock Buning, T., & Becquet, R. (2020a). Attitudes towards abortion and decision-making capacity of pregnant adolescents: perspectives of medicine, midwifery and law students in Accra, Ghana. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 25, 151–158.

- Engelbert Bain, L., Muftugil-Yalcin, S., Amoakoh-Coleman, M., Zweekhorst, M. B. M., Becquet, R., & de Cock Buning, T. (2020b). Decision-making preferences and risk factors regarding early adolescent pregnancy in Ghana: Stakeholders’ and adolescents’ perspectives from a vignette-based qualitative study. Reproductive Health, 17(141), 1–12.

- Engelbert Bain, L., Zweekhorst, L., Amoakoh-Coleman, M., Muftugil-Yalcin, M., Omolade, S., Becquet, A. I., de Cock, R., & Buning, T. (2019). To keep or not to keep? Decision making in adolescent pregnancies in Jamestown, Ghana. PLoS One, 14(9), e0221789.

- Fan, A. Z., Kress, H., Gupta, S., Wadonda-Kabondo, N., Shawa, M., & Mercy, J. (2016). Do self-reported data reflect the real burden of lifetime exposure to sexual violence among females aged 13-24 years in Malawi? Child Abuse & Neglect, 58, 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.05.003

- Hall, K. S., Morhe, E., Manu, A., Harris, L. H., Ela, E., Loll, D., Kolenic, G., Dozier, J. L., Challa, S., Zochowski, M. K., Boakye, A., Adanu, R., & Dalton, V. K. (2018). Factors associated with sexual and reproductive health stigma among adolescent girls in Ghana. PLoS One, 2(4), 13. e0195163.

- Kalembo, F. W., Zgambo, M., & Yukai, D. (2013). Effective Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Education Programs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 11(2), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.32398/cjhp.v11i2.1529

- Keogh, S. C., Leong, E., Motta, A., Sidze, E., Monzón, A. S., & Amo-Adjei, J. (2021a). Classroom implementation of national sexuality education curricula in four low- and middle-income countries. Sex Education, 21(4), 432–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1821180

- Keogh, S. C., Otupiri, E., Castillo, P. W., Li, N. W., Apenkwa, J., & Polis, C. B. (2021b). Contraceptive and abortion practices of young Ghanaian women aged 15–24: evidence from a nationally representative survey. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01189-6

- Kohler, P. K., Manhart, L. E., & Lafferty, W. E. (2008). Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(4), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026

- Krugu, J. K., Mevissen, F., Münkel, M., & Ruiter, R. (2017). Beyond love: A qualitative analysis of factors associated with teenage pregnancy among young women with pregnancy experience in Bolgatanga, Ghana. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 19(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1216167

- Kumi-Kyereme, A., Awusabo-Asare, K., & Darteh, E. K. (2014). Attitudes of gatekeepers towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 18(3), 142–153. PMID: 25438519.

- Maina, B. W., Orindi, B. O., Sikweyiya, Y., & Kabiru, C. W. (2020). Gender norms about romantic relationships and sexual experiences among very young male adolescents in Korogocho slum in Kenya. International Journal of Public Health, 65(4), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01364-9

- Melesse, D. Y., Mutua, M. K., Choudhury, A., Wado, Y. D., Faye, C. M., Neal, S., & Boerma, T. (2020). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa: Who is left behind? BMJ Global Health, 5(1), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002231

- Moreau, C., Li, M., De Meyer, S., Manh, L. V., Guiella, G., Acharya, R., Bello, B., Maina, B., Mmari, K., et al. (2019). Measuring gender norms about relationships in early adolescence: Results from the global early adolescent study. SSM Popul Health, 7, p.100314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.10.014

- Murewanhema, G., Musuka, G., Moyo, P., Moyo, E., & Dzinamarira, T. (2022). HIV and adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for expedited action to reduce new infections. IJID Regions, 5, 30–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.08.009

- Muttalib, F., Sohail, A. H., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Health of infants, children and adolescents: Life course perspectives on global health. Handbook of Global Health, 1–43.

- Ng’andu, M., Mesic, A., Pry, J., Mwamba, C., Roff, F., Chipungu, J., Azgad, Y., Sharma, A. (2022). Sexual and reproductive health services during outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics in sub-Saharan Africa: A literature scoping review. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), p. 161.

- Oppong, F. B., Logo, D. D., Agbedra, S. Y., Adomah, A. A., Amenyaglo, S., Arhin-Wiredu, K., … Ayuurebobi, K. (2021). Determinants of contraceptive use among sexually active unmarried adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years in Ghana: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(2), e043890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043890

- Owusu, S. A., Blankson, E. J., & Abane, A. M. (2011). Sexual and reproductive health education among dressmakers and hairdressers in the Assin South District of Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 15, 109–119.

- Owusu, S. A., Blankson, E. J., & Abane, A. M. (2011). Sexual and reproductive health education among dressmakers and hairdressers in the Assin South District of Ghana. African Journal Reproductive Health, 15, 109–119.

- UNFPA. (2022). World Population Dashboard – Ghana. https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/GH (Accessed 26 January 2024).

- Usonwu, I., Ahmad, R., & Curtis-Tyler, K. (2021). Parent-adolescent communication on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative review and thematic synthesis. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01246-0

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2015). A standards-driven approach to improve the quality of health-care services for adolescents.

- Ziblim, S.-D., Suara, S. B., & Adam, M. (2022). Sexual behaviour and contraceptive uptake among female adolescents (15-19 years): A cross-sectional study in Sagnarigu Municipality, Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography, 14(1).