ABSTRACT

The main aim of the study presented in this paper was to apply a new method to the creation of map typography. We focused on the original pronunciations of geographical names (endonyms), which is viewed as one of the important attributes of geographical objects.

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which was devised by the International Phonetic Association as a standardized way of representing the sounds of spoken language, was used to capture pronunciation.

The advantages and disadvantages of using pronunciation in maps were analyzed and compared with other approaches to writing names. The maps created as part of the study demonstrated the practical limitations of using the IPA in cartography. For the using of the IPA for map typography, the Middle East region was chosen because of the large number of different languages (using different scripts) spoken in it.

A map was created whose features are described by means of transcriptions of the pronunciation of geographical names in the original language. The main map also incorporates a second map, which describes the same geographical features in English, written using the IPA.

It proved to be possible to use pronunciation written in IPA characters for map descriptions, though certain limitations apply. This method may be used in cartography as a supplement to other ways of writing names.

1. Introduction

Alongside planimetry and altimetry, typography (map lettering) is one of the fundamental components of a map. Although maps without typography do exist, typography is a standard part of ordinary maps, and ‘most maps contain considerable text material’ (CitationTyner (2010)). Map typography encompasses a number of different aspects, but here the focus will be solely on geographical names (toponyms), specifically on the way in which these names are displayed in maps. CitationTyner (2010) very concisely notes that the representation of toponyms in maps may pose ‘a challenge’.

The practice of representing toponyms in maps is not globally standardized, and several different methods are used for map typography; these are listed and discussed below. The aim of the study presented in this paper was to use a new method for map typography by using the pronunciation of endonyms and the writing of the pronunciation using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). A practical example was devised in order to verify the possibilities and limitations of this method. Almost all aspects of the map creation were subordinated to this aim.

In addition to the main map (which shows the original pronunciations of endonyms), a supplementary map was also created, using the IPA to represent the English pronunciations of the English exonyms (English-speakers traditionally use the form ‘conventional name’ – CitationKadmon, 2006). The resulting cartographic work thus demonstrates two ways of using the IPA in map typography.

2. Methods of displaying geographical names in maps

Despite attempts by the United Nations to standardize geographical names and their graphic forms in the Roman script, the situation still remains complicated due to the large variety of language and writing systems used in the world. In cartography (as well as in other disciplines), the following methods are used.

2.1. Endonyms written using the locally used script

Geographical names are written in the language and script of the local population. This approach is used in the map Endonyms of the World (http://endonymmap.com/), and it is also used e.g. in the standard version of OpenStreetMap (OSM) (https://www.openstreetmap.org/); a detailed account of how OSM works with versions of names in different languages is given in CitationTutić et al. (2017).

In such cases, it is not difficult to determine the relevant forms of the names; official maps or text documents serve as the main source of information. It is, however, more challenging to determine the relevant forms of the names in the case of maps covering larger areas, depicting territories where more than one language is spoken (e.g. maps of the world), as in such cases it is necessary to use different scripts (in the case of large areas, there may be dozens of different types of scripts or variants of them).

The advantage of this method is that the map corresponds with the local language; the original names are not ‘distorted’ in any way by transcription. The resulting map can also be used when traveling in the countries depicted, as the names in the map correspond with the names used locally (e.g. on road signs).

A further advantage of this method is that it mostly preserves the link with pronunciation; the written form of the original name encodes information on its pronunciation (in accordance with the specific orthographic features of the particular language).

The disadvantage is that many scripts are unfamiliar to the average map reader, making it difficult or impossible to use the map. Another disadvantage is that a large geographical feature (such as a mountain range, a lake or sea, or a river) may have several different names if it extends over more than one country (if the name and/or the script differs between the different countries).

2.2. Endonyms written in the Roman script

The names are converted from the local script into the Roman alphabet (a process known as romanization). This approach is promoted by the UN via its United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) in conjunction with the National Names Authorities. This collaboration is one of the most extensive forms of international coordination of geographical names. Romanization is used even more extensively by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (CitationBerlin, 2005).

The advantage of this method is the single unified form (the Roman script) used for all geographical names. An entire map features just one alphabet (currently a total of 469 different characters are used for romanization – CitationUNGEGN, 2007). A further advantage is that this system enjoys widespread international support.

The disadvantage of romanization is the discrepancy between the names on the map and the local forms of the names. Although ‘the new romanization systems for international use should be considered only on condition that the sponsoring nations implemented such systems on their cartographic products (CitationUNGEGN, 2007)’, these systems are not always in general use, so the forms of the names given on a map in such cases do not correspond with the official forms of the names.

In the case of transliteration and maps with just one language, it would be possible to add a conversion table to the map. However, for maps with multiple languages, this would lead to over-complication and a decrease in clarity.

A further disadvantage of this system may be its preferential treatment of the Roman script, which in some regions is associated with colonization or foreign domination; for example, CitationUluocha (2015) notes that the colonization of Africa brought ‘a wave of Romanization and linguistic mutilation’. The issue of this preference for the Roman script is discussed further in section 4.

The use of the Roman script for map typography is naturally a major disadvantage for users who are not familiar with or proficient in this script. Although the Roman script is the most widespread script in the world, there are regions (such as China or Arab countries) where a large proportion of the population cannot use the Roman script.

2.3. Exonyms

The map typography uses exonyms, i.e. names that are in common use in the language of the authors or users of the map; this leads to the creation of maps primarily targeted at ‘domestic’ users. Examples include school atlases, where exonyms represent the most accessible form of naming for the users of the maps, being better known and more easily comprehensible than the forms used in methods 1 and 2 above. Exonyms are used e.g. in Bing Maps (https://www.bing.com/maps).

The advantage of exonyms is that they only require a single alphabet, which is familiar to the users of the map. A further important advantage is the ability to use a single nomenclature when depicting geographical features spanning areas where different languages are spoken (e.g. mountain ranges, major rivers etc.).

The disadvantage of this system is that it makes a map difficult to understand for users outside the linguistic community for which the map was designed; additionally, exonyms do not exist for all geographical features.

2.4. A combination of the above-listed methods

A combination of the above-listed methods makes it possible to eliminate some of the disadvantages of individual methods, or to exploit the advantages of these methods used. When applying romanization and exonyms, a combination with other methods is unavoidable, as neither of these methods is able to cover all the world’s geographical names.

The most common combination comprises standardized Roman transliteration alongside the use of exonyms for explanatory purposes. A combination of exonyms and endonyms is used e.g. by Google Maps. It would also be possible to use less frequent combinations and to add the romanized names of their endonyms.

2.5. Transcription based on pronunciation

A further method is the transcription of geographical names on the basis of their pronunciation. This method is not yet widely used, yet it offers a number of advantages when used in map typography.

One advantage is that information on the pronunciation is always available. Leaving aside scripts that were used to write historical or extinct languages (for which we only have access to the graphic form, and not to the authentic pronunciation), the pronunciation of modern (living) languages is always known.

Another advantage is that by transcribing pronunciation, one of the two forms of the name, graphic representation / pronunciation, is preserved. We are not creating anything new, unlike the conventional tables that are used to convert other scripts into Roman script, which generate new forms of the name – forms which previously did not exist, were not known or not used.

There is also the advantage that pronunciation exists for languages without a script – unlike the principles of transcription into Roman script, the existence of a local script is not necessary. Native languages are increasingly being studied and protected, and their pronunciation makes it possible to produce a map of the area in which the language is spoken. As part of its description of the principles for the national standardization of geographical names, UNGEGN explicitly includes the treatment of names used in unwritten languages (CitationOrth, 2006).

The advantage is that the transcription according to the local pronunciation is independent of the script type; it is a universal method which is equally valid for phonemic, syllabic or logographic scripts (as well as for unwritten languages). This method thus obviates the need to constantly create new forms of conversion.

Another advantage is that the method can be used to record the pronunciation of exonyms, as well as any other forms of a name. Even though an exonym has been formed in the recipient language, its pronunciation may nevertheless not be obvious to speakers of that language, and it may require explanation – most frequently in a dictionary, but in some cases also on a map. The pronunciation of English exonyms is recorded on the second of the maps created for this study.

Maps on which endonyms are supplemented by their pronunciations could be useful as a language teaching aid. In this case, the written form of a name, its pronunciation and the geographical reality are presented together. Students can thus expand both their geographical knowledge and their language knowledge at the same time. Teaching with such maps may also represent a more attractive and interesting way of learning than simply studying texts.

Likewise, a map may be a more interesting tool for familiarization with the characters and principles of the IPA compared with a simple text or list of words. In this case, the speaker compares a familiar pronunciation with its transcription on a map.

Pronunciation does not only concern terrestrial names. Problems with pronunciation also occur in the names of astronomical objects (e.g. CitationRumrill, 1936 and CitationConsolmagno & Reiche, 1982), which originate in numerous different languages, making it practically impossible to represent their pronunciation. The use of transcribed pronunciation as a form of supplementary information (e.g. on a map of the Moon) thus offers a potential solution.

A system of transcription already exists (i.e. the IPA), so there is no need to devise a new method. The system was created by linguists, and it continues to be refined by experts in phonetics. We thus know precisely how to transcribe a particular pronunciation. The IPA is a system that is already in use in other fields besides geography, so it represents a tried-and-tested method (see section 3).

In connection with pronunciation, it should be mentioned that besides the IPA, another method also exists whose use is made possible by current technological affordances – the use of audio recordings of geographical names. For example, when users move the cursor onto the symbol of a city on a digital map (or when they click on the symbol), an audio recording of the city’s name can be played (CitationCauvin et al., 2010; CitationFrancis, 2007). Writing about multimedia cartographic products, CitationOrmeling (2007) states that pronunciation is one of the attributes of map elements. A map is presented as the interface of a geographic multimedia database with demographic, economic and toponymic data. It enables users to access a range of attributes for the individual elements, including the pronunciation of toponyms.

The disadvantages of using a pronunciation-based typography are mainly connected with the system – the IPA. These issues are discussed in the following section.

3. The International Phonetic Alphabet

The IPA is a system that was developed by the International Phonetic Association at the end of the nineteenth century to enable the precise representation of pronunciation regardless of the user’s language. The development of the IPA from its origins to the mid-twentieth century is summarized in Albrigh (Citation1958). Current information on the IPA can be found on the website of the International Phonetic Association https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/

The IPA is an alphabet-type system based on the Roman script, which also incorporates:

upside-down or reversed Roman characters (e.g. ɯ, ɘ, ɐ),

Greek characters (e.g. ɸ, β, ε)

newly created characters (e.g. ŋ, ʕ, ʄ),

diacritic marks (e.g. p̚, t̪, ŋ̊) (CitationAshby & Maidment, 2005).

The most recent version uses 163 characters: 107 letters representing consonants and vowels, 52 diacritics and four prosodic marks – see (https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/IPAcharts/IPA_chart_orig/IPA_charts_E.html). Each character is described and explained in detail e.g. in CitationWentlent (2014).

Table 1. The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 2020).

IPA is the most widely used transcription system in the world. The IPA is used by lexicographers, students and teachers of foreign languages, linguists, speech-language pathologists, singers, actors, and translators. It is used to describe pronunciation in dictionaries and other works of lexicography. Despite current technologies enabling the use of audio reproductions of sounds (or language), written representations of pronunciation are still widely used by linguists (CitationBall et al., 2009; CitationHoward & Heselwood, 2002), and written representations may also be used in combination with video recordings of sounds (CitationNakai et al., 2016).

4. The possibilities offered by the IPA in cartography

Computers make it possible to represent all the characters in the IPA. In Unicode, the characters U+0250 to U+02AF are allocated to the IPA. The Unicode is a character coding system designed to support the display and processing of the texts of the diverse languages and technical disciplines of the modern world. It supports current and historical texts of many written languages. Unicode contains over 140 000 characters (http://www.unicode.org/standard/standard.html).

When selecting a font with IPA characters, the International Phonetic Association recommends the following: ‘With any font you consider using, it is worth checking that the symbol for the centralized close front vowel (ɪ, U+026A) appears correctly with serifs top and bottom … ’ (https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/ipa-fonts)

The advantages of using pronunciation as a basis for map typography are listed above. However, the use of the IPA for this purpose brings several disadvantages.

Although the IPA is widespread among experts, it is not well-known among the general public. Many dictionaries in various languages use the IPA to represent pronunciation, but it is not the only format used for this purpose. IPA characters are very frequently used in combination with characters that are used to write the language in question, whose pronunciation is thus evident to users. Sometimes pronunciation is represented in other formats. However, it can be assumed that familiarity with the IPA will continue to increase among the general public, partly due to the consistent use of the IPA by Wikipedia and similar projects: ‘Throughout Wikipedia, the pronunciation of words is indicated by means of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help:IPA/English.

While the universality of the IPA is its key advantage, a disadvantage is the large number of disparate characters, which can be difficult to remember. The issue concerns not only users’ inability to read IPA characters (i.e. to pronounce a word based on its IPA transcription), but also the difficulty of distinguishing between different IPA characters. The practical aspects of this problem are discussed in section 6.The disadvantage is that even among experts, the IPA is not the only phonetic alphabet in use. Others include the following:

Americanist Phonetic Notation, also known as the North Americanist Phonetic Alphabet, used mainly (though not exclusively) by American linguists to transcribe the pronunciation of native American and European languages,

the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet, for the transcription of Uralic languages,

Pinyin – the official system for transcribing Standard Mandarin Chinese into the Roman script; it is the only UN romanization system based on pronunciation. UNGEGN states that Pinyin is ‘the scheme for the Chinese phonetic alphabet’ – CitationUNGEGN (2007),

the Arabic International Phonetic Alphabet (AIPA) – see below.

A further disadvantage of the IPA is its European origin. The basic characters are derived from the Roman script, to which additional characters of various origins have been added. Nevertheless, the core of the IPA remains based on the Roman script, which may hinder the acceptance of the IPA in territories that use different scripts as well as creating an impression of the hegemonization of the Roman script. The European origins of the IPA are also reflected in its left-to-right direction, which may cause a problem when transcribing the pronunciation of languages written right-to-left (e.g. Arabic and Hebrew); this was the reason for the creation of the AIPA (CitationAlghamdi, 2006; CitationMion, 2014), which is based on the Arabic script. The AIPA includes some symbols from the IPA (as well as incorporating other symbols), but its right-to-left direction makes it more suitable for transcribing Arabic texts.

Similarly, to the use of endonyms or romanization, the use of pronunciation-based typography does not solve the problem of multiple names for geographical features spanning the territory of more than one language; the practical aspects of this issue are described in section 6. A further problem is the use of multiple languages within the same territory (e.g. when a country has more than one official language), which means that one geographical feature may have more than one name. These problems can only be removed by the use of exonyms when only one variant of the names exists.

5. The creation of the map

5.1. The choice of map area

When choosing a map area for the map, the aim was to find an area encompassing a relatively large number of different languages and scripts. It was also decided to use a relatively well-known area so that users could compare the map with their own knowledge. Further, it was necessary for the pronunciation of the names to be readily accessible. Several potential regions were identified, and the resulting map was inspired by Ortelius’s map of the ancient world (CitationOrtelius, 1590), which depicts the regions of ancient cultures, i.e. essentially the regions where the world’s most commonly used scripts originated. Only the central part of Ortelius’s map was chosen, comprising the region known today as the Middle East (CitationThe Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2020).

This map area covers approximately 7 million km2 from the western border of Libya and central Italy to the western border of Afghanistan and central Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The scripts and languages used in this map area are shown in .

Table 2. The main scripts and languages in the map area.

5.2. The content of the map

The choice of map projection was determined by the main subject of the study, i.e. the map typography. In order to minimize distortion, a conical projection would have been most appropriate, but this projection would have required the names of geographical features to be written along the lines of the parallels, i.e. in a curved configuration. When using IPA characters, which are still relatively unfamiliar to users, for ease of reading it is more appropriate to use straight configurations without any distortion of the script; for this reason, the map uses cylindrical projection in the normal position with a rectangular grid, as the degree of cartographic distortion is not important for the purposes of this particular map.

The source for the map consisted of basic data from Esri provided for ArcGIS software. Used vector data depict the basic geographical features: cities, rivers, national borders, lakes and seas. The cities depicted in the map were the capitals of the countries shown, plus all cities with a population of more than 500 000.

The maps are accompanied by a brief text characterizing the IPA. There is also a link to the website of the International Phonetic Association via a QR code, enabling the link to be quickly and easily displayed on a mobile device (telephone or tablet).

The aim was to create a wall map, so the A0 format was chosen.

5.3. Pronunciation

Besides the standard cartographic procedures used to create the map, the main task was to determine the pronunciations of selected geographical features in the original languages and to transcribe these pronunciations using the IPA.

Although the features depicted and labeled in the map are of substantial importance (mainly countries, capital cities and other large cities), and despite the huge number of dictionaries and other linguistic materials available online, it was not possible to determine the pronunciation from credible sources for all the features depicted. It is thus possible to confirm the observation of CitationZaccheddu and Jörn Sievers (2006) that ‘Additional toponymic attributes to geographical names, e.g. exonyms, the pronunciation, … are currently very rarely available’. For this reason, when transcribing a number of names (especially Arabic and Persian names) it was necessary to consult relevant experts and native speakers at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ostrava. We are particularly grateful to Parisa Changizi for her invaluable help.

When transcribing pronunciation with the IPA, the transcription is enclosed either in square brackets (for precise notation) or slashes (for simplified notation) (CitationIPA, 1999). However, when writing more lengthy texts, it is not necessary to use such enclosing symbols as long as it is clear that the text is a transcription of pronunciation (CitationAshby & Maidment, 2005; CitationIPA, 1999). Because the main map shows only pronunciation (and this fact is clear from the title of the map), no enclosing symbols were used. Square brackets were used in the supplementary map showing English pronunciation; here it was necessary to distinguish between the written form of the name (in Roman script) and the transcription of the pronunciation (IPA).

5.4. The ‘Green map’

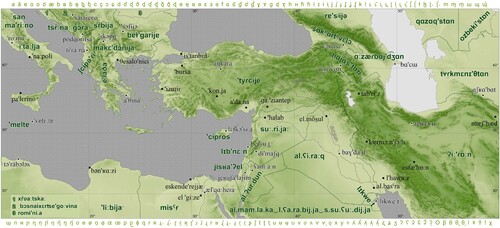

During the consultations on the pronunciation of geographical names, staff from the Faculty of Arts, University of Ostrava asked whether it would be possible to create a ‘linguistically neutral’ map as a wall decoration for the Faculty’s newly reconstructed translation and interpreting laboratory. The result was a map measuring 2.4 m (width) by 1.1 m (height). The content of the map is almost identical to that of the main map created for this study, but it uses different symbols and the color scheme is grey-green . Similarly, to the map Landscape diversity of the Czech Republic (CitationDušek & Popelková, 2017), the frame of the map consists of alphanumerical symbols – in this case the symbols of the IPA. It is merely a map field lacking a title and other compositional elements; this made it possible to avoid using any specific language for the map, and thus to meet the requirement of ‘linguistic neutrality’.

Figure 1. Wall map at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ostrava, with features described using the International Phonetic Alphabet.

6. Specifics of creating maps using the IPA

When creating the cartographic work, the aim was not only to produce a map with lettering to represent pronunciation, but also to verify the possibilities and limitations of using the IPA in cartography. The specifics of this process can be divided into two aspects: pronunciation and IPA characters.

The aim was to represent the original pronunciations of the names of individual geographical features. Leaving aside the problems of determining pronunciation described in section 5.3, this process is technically simple for features that are located within the boundaries of a single country (or within a territory where only one language is used). However, if features (such as mountain ranges, rivers or lakes) are located in more than one linguistic territory, the name of the particular feature should be displayed more than once, in the appropriate languages. This is easy to do for rivers, and it was used to label the Euphrates. It is more complicated in the case of lakes or seas: for example, the Mediterranean and the Caspian Sea are surrounded by a number of countries, and have different names and different pronunciations in those countries’ languages (for example, for the Caspian Sea it would have been necessary to give the name in Russian, Kazakh, Turkmen, Persian and Azeri.). There was no reason to favor one particular version of the name, and it would have been confusing to give all the names. Moreover, when using more than one name, it should be made clear to which country (or language) each name belongs; this would have been possible if territorial waters were marked, but such markings would have overburdened the map with information. The situation is similar in the case of mountain ranges. Here the advantage of using exonyms becomes apparent; the use of exonyms in maps is particularly beneficial when labeling large-scale features such as these. For this reason, the resulting maps left such features unlabeled; the different names could be displayed on more detailed maps which would provide enough space to do so.

The second problematic aspect was the use of IPA characters in maps. As has been mentioned when discussing the choice of projection, the main goal was to ensure that the lettering was as legible as possible. Therefore, despite the cartographic principles generally applied to descriptions of large features (CitationKrieger & Wood, 2005; CitationRobinson et al., 1995; CitationSlocum et al., 2005), the main priority when creating the map was to avoid distorting the lettering. All of the names are displayed horizontally. When using the IPA, it is also inappropriate to use gapped lettering when labeling larger areas; this is due to the IPA’s use of diacritic marks (ʰ) to denote aspirated consonants (tʰ, dʰ), its use of combinations of two symbols to denote affricates (ʦ, ʣ etc.), and its use of the undertie symbol (‿) to denote linking, i.e. the pronunciation of two words without a pause, as in the case of liaison [alʕarabijja‿s.suʕuːdijja]. There are thus certain groups of characters that cannot be separated; this means that it is not possible to used gapped lettering in a mechanical manner, as the lettering would always have to correspond with the principles of phonetic transcription. The result would be indivisible groups of characters combined with individual characters, and this would decrease the legibility of the map.

A further disadvantage of IPA characters is the absence of some lettering parameters that are used in maps to distinguish between different categories (e.g. capital letters, small letters, italics). The option of using colors remains; this is used in the map to distinguish between the names of countries, cities and water bodies.

On the other hand, one possible advantage of using the IPA is its relative unfamiliarity. As CitationTyner (2010) notes: ‘The use of an unusual typeface will sometimes make the reader stop and take notice of an otherwise uninteresting map.’

7. Conclusion

Alongside standard cartographic procedures, this study also used unusual methods for the map typography. The resulting cartographic work – in the form of a wall map (format A0) – demonstrates the possibilities for labeling geographical features on the basis of their pronunciation in the original language. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which was used for the lettering, proved to be an appropriate tool for transcribing the pronunciation of geographical names.

The study also evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of using the IPA in cartography. The original pronunciations of the names of geographical features can be found without significant problems. Transcription using the IPA is not easy for non-experts, but this method means that one of the two forms of the name (its graphic form/its pronunciation) is retained. A further advantage is that the transcription of pronunciation does not depend on the type of script normally used to write the language.

Despite these advantages, it seems unlikely that a pronunciation-based method of labeling geographical features in maps will become common. Nevertheless, the method can be used to represent the pronunciation of exonyms, and in some special cases it is also suitable for representing the original forms of geographical names.

Software

The data were displayed and processed using ArcGIS 10 software.

TJOM_1996477_Supplementary File

Download PDF (2.1 MB)Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Esri (www.esri.com) and they are provided as a basic data for ArcGIS software from Esri. Vector data and raster data were used. The raster data represent the terrain. The vector data depict the basic geographical features: cities, rivers, national borders, lakes and seas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Albright, R. W. (1958). The International phonetic alphabet: Its backgrounds and development (78 p). Indiana University Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics, Publication 7. Indiana University Press.

- Alghamdi, M. M. (2006). Design of computer codes to represent the International Phonetic Alphabet in Arabic [in Arabic]. Journal of the University King Abdulaziz: Engineering Sciences, 16(2). doi:10.4197/Eng.16-2.9

- Ashby, M., & Maidment, J. (2005). Introducing Phonetic Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-13-964370-3.

- Ball, M., Müller, N., Klopfenstein, M., & Rutter, B. (2009). The importance of narrow phonetic transcription for highly unintelligible speech: Some examples. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 34(2), 84–90. doi:10.1080/14015430902913535

- Berlin, J. (2005). Who Decides What Names Go on a Map? National Geography 09/2005.

- Cauvin, C., Escobar, F., & Serradj, A. (2010). New approaches in thematic cartography. John Willey & Sons.

- Consolmagno, G., & Reiche, H. (1982). Pronouncing the names of the moons of Saturn, or pulling teeth from Tethys. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 63(6), 6. doi:10.1029/EO063i006p00146

- Dušek, R., & Popelková, R. (2017). Landscape diversity of the Czech Republic. Journal of Maps, 13(2), 486–490. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2017.1329672

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020). Middle East. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. https://www.britannica.com/place/Middle-East

- Francis, K. (2007). Wula Na Lnuwe’kati: A Digital Multimedia Atlas. In W. Cartwright, M. P. Peterson, & G. Gartner (Eds.), Multimedia Cartography. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-36651-5_10.

- Howard, S. J., & Heselwood, B. C. (2002). Learning and teaching phonetic transcription for clinical purposes. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 16(5), 371–401. doi:10.1080/02699200210135893

- IPA. (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. International Phonetic Association, Cambridge University Press.

- Kadmon, N. (2006). Exonyms, also called conventional names. In Manual for the national standardization of geographical names (pp. 129–131). United Nations.

- Krieger, J., & Wood, D. (2005). Making Maps: A Visual Guide to Map Design for GIS. The Guilfod Press.

- Mion, G. (2014). Arabiser la phonétique. L'arabisation de l’Alphabet Phonétique International. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 67/3.

- Nakai, S., Beavan, D., Lawson, E., Leplâtre, G., Scobbie, J. M., & Stuart-Smith, J. (2016). Viewing speech in action: speech articulation videos in the public domain that demonstrate the sounds of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, doi: 10.1080/17501229.2016.1165230

- Ormeling, F. (2007). Map Concepts in Multimedia Products. In W. Cartwright, M. P. Peterson, & G. Gartner (Eds.), Multimedia Cartography. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-36651-5_8.

- Ortelius, A. (1590). Aevi Veteris, Typus Geographicus. Antwerp. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~275811~90048742

- Orth, D. J. (2006). Standardization procedures. In Manual for the national standardization of geographical names (pp. 33–39). United Nations.

- Robinson, A. H., Morrison, J. L., Muehrcke, P. C., Kimerling, A. J., & Guptill, S. C. (1995). Elements of Cartography. John Wiley & Sons.

- Rumrill, H. B. (1936). Star name pronunciation. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 48(283), 139–154. doi:10.1086/124681

- Slocum, T. A., McMaster, R. B., Kessler, F. C., & Howard, H. H. (2005). Thematic Cartography and Geographic Visualization. Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-130-35123-7.

- Tutić, D., Jogun, T., Kuveždić Divjak, A., & Triplat Horvat, M. (2017). World political map from OpenStreetMap data. Journal of Maps, 13(1), 67–73. doi:10.1080/17445647.2017.1323683

- Tyner, J. A. (2010). Principles of Map Design. The Guilford Press.

- Uluocha, N. O. (2015). Decolonizing place-names: Strategic imperative for preserving indigenous cartography in post-colonial Africa. African Journal of History and Culture, 7(9), 180–192. doi:10.5897/AJHC2015.0279

- UNGEGN. (2007). Technical reference manual for the standardization of geographical names. UN.

- Wentlent, A. (2014). Alfred's IPA Made Easy: A Guidebook for the International Phonetic. Alfred Music. ISBN 978-1-4706-1561-1.

- Zaccheddu, P.-G., & Jörn Sievers, J. (2006). EuroGeoNames (EGN) – developing a European Geographical Names Infrastructure and Services. UNGEGN.