ABSTRACT

Geotourism is a form of nature-oriented tourism devoted to the knowledge and understanding of landscape forms and geological processes; flora and fauna and cultural, historical and human heritage. The great geological and morphological variability of Avellino Province, also called Irpinia, in southern Italy makes this province of particular interest for geotourists. Irpinia has a unique set of geosites, sites of cultural interest, archaeological sites and natural parks. Additionally, since ancient times, it has been a transit route between the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic Seas and, as in all countries of the Mediterranean area, it was dominated by different races, peoples and cultures that contributed to developing its cultural identity and heritage, including its food and wine. Indeed, some Irpinian products were already known and commercialised in Roman times, including wine and olive oil. On this basis, we propose a map showing the characteristics of Avellino Province, including sites of geological, historical-archaeological and cultural value. The map will contribute to a better understanding of this province from a geotourism perspective and might guide tourists through knowledge of Irpinia.

1. Introduction

In the last 20 years the practice of geotourism, which is an emerging form of nature-oriented tourism (CitationHose, Citation2008), has been developing all over the world (CitationÓlafsdóttir & Tverijonaite, Citation2018). According to CitationDowling (Citation2013) and CitationVanneste and Vandeputte (Citation2016), geotourism has a number of similarities with eco- or cultural tourism. CitationDowling and Newsome (Citation2006, Citation2008) argued that the practice of geotourism consists of a journey through geological sites and landscapes that is devoted to the knowledge and understanding of their typical forms and processes, of flora and fauna and of human cultural and historical heritage. In this definition, CitationDowling and Newsome (Citation2006, Citation2008) and CitationNewsome et al. (Citation2012) consider natural and anthropological assets as interacting elements, which variously combine in a geographic itinerary. CitationStueve et al. (Citation2002) and CitationHose (Citation2008) suggested that geotourism sustains or enhances the geographical character of a place, including its environment, culture, aesthetics and heritage, to sustain its residents. Museums, libraries, archival collections and artistic outputs, including social history and industrial archaeology, are also considered of interest for geotourism.

Geotourism has spread over the past two decades in many regions of the world (CitationRuban, Citation2015) like Europe (Poland and Italy), East Asia (China), the Middle East (Jordan) and South America (Brazil). In Italy, geotourism is commonly associated with multiple forms of sustainable tourism, such as trekking and religious hiking, cycle-tourism and horse touring. These new forms of tourism are mainly practiced by young people (∼40% middle and high school students), commonly involved in environmental education programmes and green vacations. Only a small fraction of adults (∼25%) practice trekking and hiking (CitationCamerlenghi, Citation2006) in the context of cultural and anthropological guided excursions or participate in traditional events and enological and gastronomic festivals oriented to the knowledge of specific regional products. Recent data from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (i.e. ISTAT) confirm that these new tourism trends have progressively increased in recent years. Indeed, at the end of 2019, tourist counts in Italy included 131.4 million arrivals and 436.7 million attendees, for total growth of 2.6% and 1.8%, respectively, in comparison with the previous year (http://www.istat.it, CitationISTAT Citation2020).

In the last decade, the diffusion of geotourism practices has consistently increased as a consequence of valuing the landscape and the architectural and monumental heritage of Italy, through national and international recognition practices 9 e.g. Borghi più belli d’Italia—Most Beautiful Villages in Italy; Bandiere Arancioni del Touring Club Italiano – Orange Flags of the Italian Touring Club; Borghi Autentici d’Italia – Authentic Villages of Italy; Fondo Ambiente Italiano (FAI) – The National Trust for Italy; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation sites]. In addition, a growing number of protected areas have been established across Italy with positive consequences for the local and national economy. Regional, provincial and local authorities have been working to promote the value of such activities through dedicated financial support.

In this context, Avellino Province in southern Italy, also called Irpinia, is an example of valuing cultural and territorial assets with geotourism (CitationRusso & Sisto, 2012) to its outstanding archaeological, monumental and archival resources. The presence of a considerable number of protected natural areas, associated with limited urbanisation, make Avellino Province a typical rural landscape that fully represents the assets of the Apennine Mountains of southern Italy and their bio- and geodiversity (sensu CitationGray, Citation2004; geosites, sensu CitationReynard et al., Citation2014; geomorphosites, sensu CitationPanizza, Citation2001).

In this context, the landscape is intended as a real and valuable resource to promote through nature-oriented tourism (CitationGordon, Citation2018; CitationSisto et al., Citation2020). This requires further engagement by local authorities that should adopt specific measures to preserve their assets (concept of geoconservation sensu CitationGordon et al., Citation2018) and specific educational models (geoeducation sensu CitationPanizza & Piacente, Citation2003; CitationAllan, Citation2015; CitationBollati et al., Citation2015; CitationSantangelo et al., Citation2015). Geodiversity promotes regional development, especially in cases of demographic and economic underdevelopment (CitationBujdosó et al., Citation2015). These conditions are common in southern Italy and in Avellino Province (i.e. Irpinia; CitationCresta & Greco, Citation2010; CitationDi Lisio et al., Citation2016a). It is clear that knowledge of the value of this geological diversity and adoption of new forms of sustainable slow-tourism through the development of specific itineraries is of basic importance in this perspective.

On this basis, and to contribute to better understanding of this province from a geotourism point of view and guide tourists through its knowledge, a geotourism map of Avellino Province, known for its differentiated cultural and natural asset and for a multitude of high-quality products and colourful traditions, is here presented.

1.1. Study area

Avellino Province extends for 2805 km2 across the southwestern sector of the Apennine mountains in southern Italy. The provinceincludes part of the Picentini Mountains in the south, with elevations up to 1900m above sea level (a.s.l.; e.g. Polveracchio Mt., Terminio Mt.). In this sector, the longest rivers in the province, the Calore and the Sabato, develop. The western sector of the province is characterised by the Avella–Partenio Mountains, with elevations up to 1600 m a.s.l that form the boundaries with Napoli and Caserta provinces to the west and north, respectively. The northern sector of the province, the so-called Alta Irpinia, has a mainly hilly morphology with isolated elevations of approximately 1000 m a.s.l. In this sector, the Ofanto is the main river. Mountainous areas (higher than 600 m a.s.l.) span 23% of the total province area, and hilly and flat lands extend for approximately 65% and 12%, respectively.

Avellino Province is equidistant between the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic coasts. Hosting the Apennine watershed line, the province is characterised by a variety of natural and geological environments. In general, the climate is a temperate Mediterranean type. It is strongly influenced by humid air masses of Tyrrhenian origin that produce orographic effects on the main reliefs. Winters are cool and rainy (max 160 mm precipitation) with temperatures that rarely drop below 0°C, except for the altimetric effect of mountains where the temperature drops to several degrees below zero and snowfalls are frequent (for details about local conditions see the inset climatic diagrams on sheet 1 of the Main Map. The summer is generally hot and dry with average temperatures around 25°C.

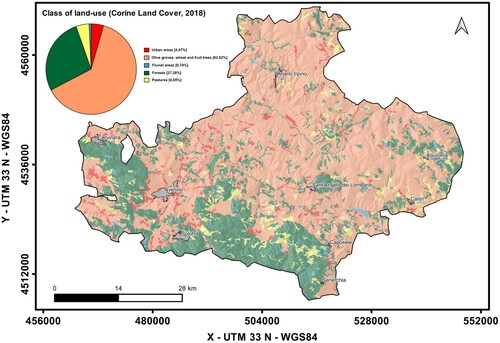

Land use is quite variable over the province, with 63% of its surface characterised by agricultural use and 4.5% used as pasture. Forests cover 27% of the surface of Avellino Province while only 4.5% is urbanised (Corine Land Cover, 2018; ).

Figure 1. Land use map of the Avellino Province. Inset graph indicates statistical distribution of land use classes. (Corine Land Cover (CLC) 2018, Version 2020_20u1- https://land.copernicus.eu/pan-european/corine-land-cover/clc2018)

The town of Avellino with its 54,716 inhabitants is the most relevant urban centre of the province. Overall, Avellino Province has 418,306 inhabitants distributed in 118 municipalities, 17 of which have more than 5,000 inhabitants. The average population density is 149 people/km2. The scarce urbanisation and widespread hills make Avellino Province particularly suited to agricultural practice, with high-value production of typical products like wine and olive oil. The poorly developed rail network is somewhat compensated for by the A16 motorway (Napoli–Canosa; European Road E842) that passes through the province. The road network is well developed, with a number of segments connecting the town of Avellino with prominent towns in the surrounding provinces.

1.2. Data and methods

The 1:100,000 geotourism map of Avellino Province was made using data derived from a literature review (i.e. regional and national tourism and geology guides; CitationCalcaterra et al., Citation2016; CitationCorvino, Citation2004; CitationRegione Campania, EPT Avellino Citation2015; CitationGAL Irpinia, Citation2013; CitationItalian Touring Club, Citation1999; Citation2015; CitationMarano & Mazzei, Citation2015; CitationPiedimonte, Citation2016; CitationRescio, Citation2017; CitationRumiz, Citation2016; CitationSlow Food Italia, Citation2013) and available databases of regional and national relevance (). Other elements like the geological framework (), sites of geological importance (i.e. mines, landslides, springs, caves, lakes, peaks, panoramic points, etc.; Supplementary materials 1 and 2), places of cultural relevance (i.e. castles, museums, etc.; Supplementary materials 3), archaeological sites and ancient roads (Supplementary materials 4), natural parks (Supplementary materials 5), shrines and place of worship (Supplementary materials 6) and the Most Beautiful Villages of Italy and Ghost Towns (Supplementary materials 7), have been collected, organised in a dedicated database and used as relevant information for map production (sheets 1 and 2).

Table 1. Main data sources.

Table 2. Main features and places of outcrops of geologic complexes.

The two 1:140,000 maps of supplemental features (Sheet 2), were produced using the same shaded relief base of the 1:100,000 Main Map (Sheet 1). The supplemental features maps report characteristic data derived from specific tourist guidebooks (http://www.incampania.com/; CitationGal Irpinia, Citation2013; CitationMarano & Mazzei, Citation2015; CitationSlow Food Italia, Citation2013) and from the Campania Regional database consisting of: a) food and wine production information, and b) festival and popular tradition information obtained from the guidebook Avellino e la sua provincia (Avellino and its province), produced by Regione Campania and several interviews with elderly people.

The 1:400,000 supplemental maps also show the extent of the most important wine-growing terroirs in Avellino Province, as listed in the national database (https://www.politicheagricole.it) of the Ministry for Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies.

2. The geotourism map of Avellino Province

The Main Map (Sheet 1) reports all relevant features and elements of geotouristic value surveyed in Avellino Province. They include the geological framework of the territory, sites of geological and geomorphological relevance, natural and protected areas, historic and cultural sites, places of worships and archaeological sites, etc. Other elements of interest for tourism like roads, motorways, etc. are also reported. All these features are depicted on a shaded-relief base map.

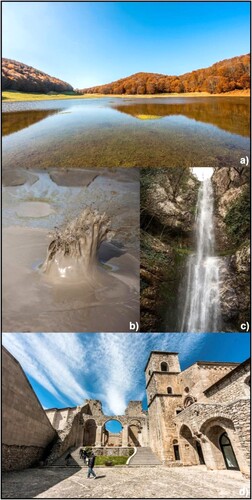

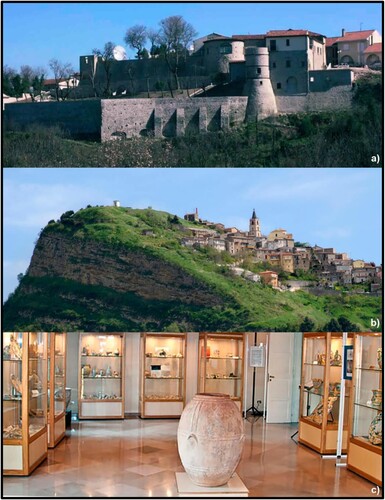

Four geological complexes have been identified: 1) the post-orogenic complex G1, 2) the late synorogenic complex G2, 3) the siliceous orogenic complex G3, and 4) the carbonate orogenic complex G4. Descriptions of the main features of the geologic complexes, as well as their principal outcrops, are reported in . Sites of geologic, palaeontologic and geomorphologic interest such as the Campo Maggiore endorheic basin located within the Avella–Partenio Mountains, the Bolle della Malvizza hydrothermal field in the Miscano river basin and the Acquaserta waterfall in Quadrelle are depicted in the Main Map ( a, b and c). Major landslides like that of Montaguto (e. g. CitationGuerriero et al., Citation2013; CitationGuerriero et al., Citation2014; CitationPinto et al., Citation2016), are also reported in the Main Map and descriptions of additional relevant sites are reported in the Supplementary materials 1 and 2. Similarly, sites of cultural interest like castles, museums and monuments are depicted; a specific list is provided within the Main Map and a brief description of the most relevant sites is provided in Supplementary materials 3. Prominent examples include the D’Aquino castle of Grottaminarda, the old town of Cairano and the People Without History museum in Altavilla Irpina (). Archaeological sites such as the old town of Aequum Tuticum, Carbonara and shelters like that at the top of Mt. Raiamagra, are depicted. Additional relevant archaeological sites are described in Supplementary materials 4. In addition, natural parks and protected areas are reported in the Main Map and described in Supplementary materials 5.

Figure 2. (a) Campo Maggiore endorheic basin, Avella–Partenio Moutains. (b) Bolle della Malvizza hydrothermal area. (c) Acquaserta waterfall. (d) Goleto Abbey. (Photo courtesy of Bocchino G.).

Figure 3. (a) D’Aquino castle of Grottaminarda. (b) old town of Cairano. (c) People without History Museum in Altavilla Irpina.

Major shrines and places of worship are shown on the map and detailed in Supplementary materials 6.

The province of Avellino, like the surrounding ones, has been hit over the centuries by numerous destructive earthquakes (1456, 1688, 1702, 1930, 1962 and 1980) that caused serious loss of life in local communities and significant material damage to buildings, infrastructure and monuments. The earthquakes on 23 July 1930 and 23 November 1980 (Magnitude 6.6 and 6.9, respectively; X degree on the Mercalli Scale) had their epicentres in central-western Irpinia (see Main Map sheet 1) and were the most disastrous in the recent history of this province. The signatures of such catastrophic events, related to earthquake effects, are evidenced by reconstructions, relocations and sudden or progressive abandonments of ancient historical centres. It is still possible to find so-called ghost towns or sleeping beauties (CitationMocciola, Citation2014 and CitationArminio, Citation2003, Supplementary materials 7). The most characteristic of these ancient and abandoned villages are reported on the Main Map (Sheet 1).

Beautiful villages of national relevance such as Monteverde and Summonte, as well as major shrines and relevant places of worship like Goleto Abbey (d) are reported in the map and described in Supplementary materials 7.

Inset map 1 (Sheet 2) reports both certified and not-certified typical products of Avellino Province, providing information about locations and zones of production. Montella chestnuts, the coppery onions of Montoro and San Marzano tomatoes are example of typical certified products from Avellino Province. Additional examples are shown in . Inset map 2 (Sheet 2) reports the extent of terroir for grapes used in the most famous wine production of the province such as Greco di Tufo, Taurasi and Fiano.

Figure 4. (a) Paternopoli garlic, (b) Caciocavallo Irpino, (c) Carmasciano, (d) Melella cherry. (e) Montoro onion. (f) Juncata Irpina, (g) Matasse Calitrane pasta, (h) Avellane hazelnuts, (i) Ravece olive oil, (j) Montecalvo bread, (k) Jummaro bread. (l) Pecorino Bagnolese cheese, (m) Peperoni Quagliettani, (n) San Marzano tomatoes, (o) Montella chestnuts, (p) Taurasi wine.

To enrich the cultural content and provide further information of interest to tourists, that can also represent an element of geotourism, inset map 3 (Sheet 2) reports major events like patron saint festivals, culinary festivals, sacred representations, etc. The carnival of Montemarano, the Zeza of Mercogliano, the Cavalcata di St. Anna of San Mango sul Calore and Il Giglio of Flumeri are examples of such festivals and traditions ().

3. Conclusions

The Main Map provides an overview of the distribution of touristic features over a simplified geologic base-map, shown as three maps in two separated sheets. Sites of geological and geomorphological relevance, sites of cultural interest, beautiful villages, shrines, places of worship, archaeological sites and natural parks are presented in a simplified manner to make the map readily suitable for geotourists. Inset maps provide an overview of high-value typical food products that can be tasted in specific places in the province, terroir of high-quality wines and seasonal festivals and traditions.

In conclusion, with this approach we think we have created a geotourism map that is an important tool for conservation and enhancement of the heritage and other numerous tourist resources of Avellino Province.

Software

The map was prepared using Quantum GIS, Open Source Geographic Information System, licensed under the GNU General Public License. Quantum GIS is an official project of the Open Source Geospatial Foundation (OSGeo, public domain software).

TJOM_2004941_Supplementary_material

Download PDF (28.1 MB)Acknowledgements

We thank Rannveig Ólafsdóttir, Juliane Cron, Paola Petrosino and Paola Coratza for their constructive reviews of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Angelo Cusano ([email protected]), upon reasonable request.

References

- Allan, M. (2015). Geotourism: an opportunity to enhance geoethics and boost geoheritage appreciation. In: Geological Society, London. Special Publications, 419(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP419.20

- Arminio, F. (2003). Viaggio nel cratere. Sironi Editore, 184.

- Basso, C., Di Nocera, S., Matano, F., & Torre, M. (1996). Evoluzione Geomorfologica ed ambientale tra il Pleistocene Superiore e L’Olocene dell’area tra Castelbaronia e Vallata nell’alta valle del F. Ufita. Il Quaternario – Italian Journal of Quaternary Sciences, 9, 513–520.

- Bollati, I., Coratza, P., Giardino, M., Laureti, L., Leonelli, G., Panizza, M., Panizza, V., Pelfini, M., Piacente, S., Pica, A., Russo, F., & Zerboni, A. (2015). Directions in geoheritage studies: Suggestions from the Italian geomorphological community. In Engineering geology for society and territory – Preservation of cultural heritage, V. 8, (pp. 213–217). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09408-3_34.

- Bujdosó, Z., Dávid, L., Wéber, Z., & Tenk, A. (2015). Utilization of geoheritage in tourism development. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.400 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.400

- Calcaterra, D., D’Argenio, B., Ferranti, L., Pappone, G., & Petrosino, P.. (2016). Guide Geologiche Regionali – Campania e Molise. In Italian Geological Society (pp. 276).

- Camerlenghi, F. (2006). Ruolo e mansioni del personale operativo nel settore del turismo naturalistico e scientifico. Atti del Convegno Nazionale “Il Patrimonio Geologico: una risorsa da proteggere e valorizzare”.

- Ca.Re.Geo. (2008). Catasto Regionale dei Geositi. Regione Campania. L.R. 13 del 13 ottobre 2008. http://www.difesa.suolo.regione.campania.it/.

- Corvino, C. (2004). Storie Irpine. Franco Muzio Editor (296 pp).

- Cresta, A., & Greco, I. (2010). Luoghi e forme del turismo rurale. Evidenze empiriche in Irpinia. Franco Angeli Editor (217 pp).

- Di Lisio, A., Iscaro, C., Russo, F., & Sisto, M. (2016a). Geotourism and Economy in Irpinia (Campania, Italy). Rend. Online Soc. Geol. It, 39, 72–75. https://doi.org/10.3301/ROL.2016.50

- Dowling, R. K. (2013). Global geotourism. An Emerging Form of Sustainable Tourism. Czech Journal of Tourism, 2, 59–79. https://doi.org/10.2478/cjot-2013-0004

- Dowling, R. K., & Newsome, D. (Eds.). (2006). Geotourism (pp. 260). Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann.

- Dowling, R. K. & Newsome, D. (Eds.). (2008). Geotourism. Proceedings of the Inaugural Global Geotourism Conference, ‘Discover the Earth Beneath our Feet’, Fremantle, Western Australia, 17-20 August. Promaco Conventions Pty, Ltd, pp. 478.

- GAL Irpinia. (2013). Quattro Stagioni in Irpinia. GAL Irpinia (70 pp).

- Gordon, J. E. (2018). Geoheritage, Geotourism and the Cultural Landscape: Enhancing the Visitor Experience and Promoting Geoconservation. Geosciences, 8, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8040136

- Gordon, J. E., Crofts, R., & Díaz-Martínez, E. (2018). Geoheritage conservation and Environmental Policies: Retrospect and Prospect. In: Emmanuel Reynard and José Brilha, editors, Geoheritage. Assessment, Protection, and Management. Chapter, 12, 213–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809531-7.00012-5

- Gray, M. (2004). Geodiversity valuing and conserving abiotic nature (p. 434). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Guerriero, L., Coe, J. A., Revellino, P., Grelle, G., Pinto, F., & Guadagno, F. M. (2014). Influence of slip-surface geometry on earth flow deformation. Montaguto Earth Flow, Southern Italy. Geomorphology, 219, 285–305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.04.039

- Guerriero, L., Revellino, P., Grelle, G., Fiorillo, F., & Guadagno, F. M. (2013). Landslides and Infrastructures: The case of the Montaguto earth flow in Southern Italy. Ital J Eng Geol Environ Book Ser, 6, 447–454.

- Hose, T. A. (2008). Towards a history of geotourism: Definitions, antecedents and the future. Geological Society London Special Publications, 300(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP300.5 https://doi.org/10.1144/SP300.5

- ISTAT. (2020). Il movimento turistico in Italia. Report, statistiche Istat, 2020, 1–14. http://www.istat.it.

- Italian Touring Club. (1999). Guida Touring – Parchi e aree protette d'Italia. Touring Editor (475 pp.).

- Italian Touring Club. (2015). Guide Verdi d'Italia – Campania. Touring Editor (284 pp.).

- Marano, M., & Mazzei, R. (2015). Guida ai prodotti tipici del territorio. Gal Irpinia (77 pp.).

- Mocciola, A. (2014). Le belle addormentate. Nei silenzi apparenti delle città fantasma. Alla riscoperta di un’Italia dimenticata. Betelgeuse Editore Srl, Verona (189 pp.).

- Newsome, D., Dowling, R. K., & Leung, Y. F. (2012). The nature and management of geotourism: A case study of two established iconic geotourism destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 2–3, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2011.12.009

- Ólafsdóttir, R., & Tverijonaite, E. (2018). Geotourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Geoscience, 8(7), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8070234.

- Panizza, M. (2001). Geomorphosites: concepts, methods and examples of geomorphological survey. Chin. Sci. Bull, 46, 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03187227

- Panizza, M. & Piacente, S. (2003). Geomorfologia culturale. Pitagora Editor Bologna (408 pp.).

- Piedimonte, A. (2016). Nella terra delle Janare – Viaggio nell’Irpinia segreta, tra legende, magia e mostri. Intra Moenia Editor (223 pp.).

- Pinto, F., Guerriero, L., Revellino, P., Grelle, G., Senatore, M. R., & Guadagno, F. M. (2016). Structural and lithostratigraphic controls of earth-flow evolution, Montaguto earth flow, Southern Italy. J Geol Soc, 173(4), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2015-081

- Regione Campania, EPT Avellino. (2015). Avellino e la sua provincia (143 pp). Regione Campania.

- Rescio, P. (2017). Via Appia Strada di Imperatori Soldati e Pellegrini – Guida al percorso e agli itinerari. Schena Editor (p. 269).

- Reynard, E., Perret, A., Buchmann, M., Bussard, J., Grangier, L., & Martin, S. (2014). A method for assessing the intrinsic value and management potentials of geomorphosites. Geophys Res Abstr, 16, EGU2014-9201-1.

- Ruban, D. A. (2015). Geotourism. A geographical review of the literature. Tourism Management Perspectives, 15, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.03.005.

- Rumiz, P. (2016). Appia. Feltrinelli Editor 360 pp).

- Russo, F., & Sisto, M. (2012). Valorisation culturelle et économique à travers le Géotourisme d’un territoire marginal: l’Irpinie (Campanie, Italie). In Volumes des Actes du Colloque international de Géomorphologie «Géomorphosites 2009: imagerie, inventaire, mise en valeur et vulgarisation du patrimoine géomorphologique (pp. 287–293). Université Sorbonne Paris.

- Santangelo, N., Romano, P., & Santo, A. (2015). Geo-itineraries in the Cilento Vallo di Diano Geopark: A Tool for Tourism development in Southern Italy. Geoheritage, 7(4), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-014-0133

- Sisto, M., Di Lisio, A., & Russo, F. (2020). The mefite in the Ansanto Valley (Southern Italy): A geoarchaeosite to promote the geotourism and geoconservation of the Irpinian cultural landscape. GeoHeritage, 12, 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00450-x.

- Slow Food Italia. (2013). Irpinia – Tra boschi, borghi e castelli medievali, sulle strade del Taurasi, del Greco di Tufo e del Fiano d’Avellino. Slow Food and Touring Editors, 173.

- Stueve, A. M., Cook, S. D., & Drew, D. (2002). The Geotourism Study: Phase 1 Executive Summary ((p. 22)). WTA.

- Tarquini, S., Isola, I., Favalli, M., Mazzarini, F., Bisson, M., Pareschi, M. T., & Boschi, E. (2009). TINITALY/01: A new triangular irregular network of Italy. Annals of Geophysics, 50, 407–425. https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-4424

- Vanneste, D., & Vandeputte, C. (2016). Geotourism and the underestimated potential of ‘ordinary’ landscapes. The Belgian case. Proceedings of TCL2016 Conference, INFOTA (pp. 587–598).

- Vitale, S., & Ciarcia, S. (2018). Tectono-stratigraphic setting of the Campania region (southern Italy). J. Maps, 14, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2018.1424655