Background of Jain and Sikh studies project at Loyola Marymount University

This special interreligious issue on ‘The Music and Poetics of Devotion in the Jain and Sikh Traditions’ is the product of papers adapted from those presented at the first Sikh-Jain conference held at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, 25–27 February 2016. It was made possible by a three-year endowment from generous individuals in the Jain and Sikh communities as well as the Uberoi Foundation who created a Clinical Professorship in Sikh and Jain Studies at LMU (2015–2018) focused on teaching, organizing conferences, and community outreach to bring the Sikh and Jain communities as well as University faculty and students into conversation.Footnote1

The Jain and Sikh Studies project developed in the Department of Theological Studies at LMU due to a recognition of the need for more interreligious cooperation and support to enhance scholarship on these ‘minority’ traditions. This interreligious project arose from a friendship between two stalwarts from the Jain and Sikh Communities, Dr. Sulekh Jain a mechanical engineer, professor, author, and Ahimsa advocate and Dr. Harvinder Singh Sahota, the father of the perfusion balloon in angioplasty, generous supporter of Sikh Studies and Sikh awareness advocate. It was their vision to bring to light the historical cooperation, care and confluence of arguably the most ancient and most recent Indian religious traditions, Jainism dedicated to letting others live (ahimsa), and Sikhism dedicated to helping others to live (seva).

Theme and rationale for the conference

The theme for our first conference ‘The Music and Poetics of Devotion’ arose from my own background, scholarship and interest in the topic. In 2000 I began practicing the Sikh drumming tradition, the Amritsārī-Kapurthala bāj on the jorī-pakhāwaj, becoming its first female exponent. This led to my dissertation research at the University of Michigan on ‘The Renaissance of Sikh Devotional Music: Memory, Identity, Orthopraxy’ (Citation2014). Through my research I gained an appreciation for the centrality of sonic expression and experience within religious practice. Emotive language and musical modes are effective tools to teach and transmit tradition over time, while promoting communal cohesion, meditative entrainment, and mystical engagement. This is the case for both Jain Stavan and Sikh kīrtan, whose music is sung for devotion, worship, ritual, liturgy, and life-cycle events, though with distinctive styles, purposes and aims. Jain Stavan, also referred to as Bhajan, is predominantly sung by women to praise a Jina (liberated one) and convey important theological concepts.Footnote2 Sikh kīrtan on the other hand, is a genre historically dominated by male professionals who sing hymns primarily from the Guru Granth Sahib.

We find broad points of connection between these musico-poetic traditions including historic and geographic links to the 15th-17th c. Bhaktī milieu, where the primary compositions of both traditions serve central functions in daily practice. These compositions are commonly sung either solo or in community in the folk music genres. While ‘classical’ rāga melodies can be found listed on some Jain texts, it is a more prominent feature of Sikh kīrtan, though within both traditions, modern Bollywood inspired tunes are now commonly sung, creating debates in regards to the music’s authenticity and efficacy (Khalsa Citation2012). Sikh and Jain musico-poetic texts share a similar poetic structure written in the pada form, in local dialects, utilizing alliteration and rhyme along with the emotive rasa aesthetic to convey the mood of the poetry. This multi-layered confluence in such musico-poetic engagements has a psycho-somatic impact, enabling expansive experiences of these emotive modes of expression that go beyond our normal, everyday languaging. Scientific studies are now demonstrating how group ritual engagement syncs heart rates and provides for heightened and cohesive communal experiences. In other words, religious music and poetry offer practitioners communal and ritual engagement as well as meditative experience, leading the mind toward more enlightened states of consciousness.

In line with the interdisciplinary nature of the conference, the papers addressed a diverse and wide range of topics including ethnomusicology, musicology, performance, gender, history, hermeneutics, literary analysis, modernization, pedagogy, professionalization, mysticism, and lived practice. While most papers focused on the scholar’s area of specialization – either the Jain or Sikh musico-poetic tradition – this conference sparked productive interfaith dialogue and scholarly engagement, asking questions through different interpretive lenses which are used to read music and poetry along with history, scripture, literature, lived practice, and oral tradition. We hope the breadth of questions being asked and engagement with various issues, insights and intersections within this interfaith project continues to expand our horizons within the field.

Conversations and connections

The conference brought together top international scholars in the field of Jain or Sikh music and poetry. Sikh scholars included Francesca Cassio (Sardarni Harbans Kaur Chair in Sikh Musicology, Hofstra University), Bhai Baldeep Singh (Dean of Humanities and Religious Studies, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar and Founder Anad Conservatory), Nikky-Guninder K. Singh (Crawford Family Professor of Religion and Chair, Department of Religious Studies, Colby College), Charles Townsend (Associate Professor, Humanities and Philosophy, Oakton Community College), and myself (Clinical Professor Jain and Sikh Studies, Instructor Theological Studies, Loyola Marymount University). Independent scholar and historian of South Asian music, Bob van der Linden, offered a comparative perspective on both the Jain and Sikh musical traditions. Jain scholars included Whitney Kelting (Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Northeastern University), Ellen Gough (Assistant Professor of Religion, Emory College), Aleksandra Restifo (Junior Research Fellow, Oxford), Sander Hens (Graduate Student, Jaina Studies, Ghent University), and Adrian Plau (Graduate Student, SOAS University of London) who did not attend the conference but graciously contributed his paper to this volume. Serving as respondents were senior scholars Christopher Key Chapple (Doshi Professor of Indic and Comparative Theology, Director, Master of Arts in Yoga Studies, LMU) and Pashaura Singh (Professor and Jasbir Singh Saini Endowed Chair of Sikh and Punjabi Studies, University of California Riverside).

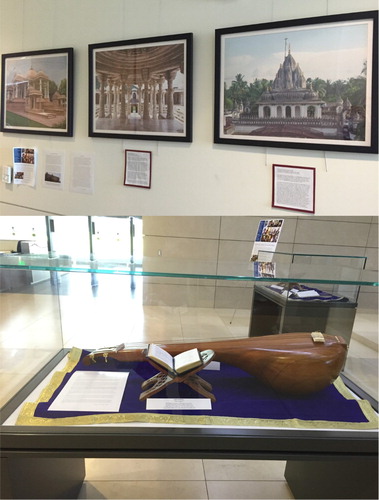

As a complement to the engaging and productive scholarly dialogue, I also curated two evening concerts as well as a month-long library exhibit at the William H. Hannon Library so attendees as well as LMU faculty, staff and students could learn more about these traditions through holistic engagement. The library exhibit displayed Jain and Sikh musical and religious instruments, photographs, artifacts, and scriptures. The videos from the concerts and conference papers can be watched on the LMU Yoga Studies Youtube Channel, so the reader may further experience the breadth and depth of the music and ideas discussed in this volume.

A section of the ‘Music and Poetics of Devotion’ exhibit at William H. Hannon Library, LMU. Tanpurni handcrafted by Bhai Baldeep Singh. Photo taken by author.

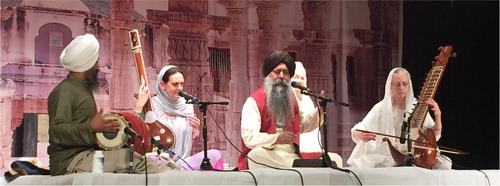

Sonic Pilgrimage Concert with Francesca Cassio (center), Nirvair Khalsa on taus, Parminder Bhamra on pakhāwaj, Nirinjan Khalsa-Baker on jorī. Photo courtesy Gurumeet S. Khalsa.

The two conference evenings were filled by Sikh kīrtan and Jain Stavan/Bhajan concerts which drew audiences from the broader Sikh, Jain, and South Asian musical, academic, and religious communities. The first night began with a Sikh kīrtan concert by Francesca Cassio who created a meditative atmosphere in LMU’s Ahmanson Auditorium, taking the audience on the musical journey of a Sikh sonic pilgrimage as discussed in her paper. Parminder Singh Bhamra traveled from Italy to offer his skillful accompaniment on the pakhāwaj, Nirvair Kaur Khalsa artfully accompanied on the taus, with myself joining on the jorī-pakhāwaj.

To close the evening, members of the Bhaktī Bhavana group and Mahila Mandal from the Jain Center of Southern California delighted the audience with popular Jain Bhajans sung by vocalists Nikhil Dhami, Bharatkumar Shah, and Dipikaben Shah accompanied by Amrish Bhojak on tabla and Rajeshbhai Parikh on keyboard.

The second night of concerts was graciously hosted at the Jain Center of Southern California, enabling conference speakers, participants and attendees to engage directly with the Jain Temple community. The night began with Jain musician Vina Jhaveri who traveled from Cincinnati, Ohio especially for this concert. The audience appreciated her solo renditions of well-known Stavans in popular melodies. She was also accompanied by Amrish Bhojak on tabla and Rajeshbhai Parikh on harmonium.

Gurbānī Sangīt concert given by Bhai Baldeep Singh at Jain Center of Southern California. Photo taken by author.

A highlight was the illuminating concert given by Bhai Baldeep Singh, thirteenth generation exponent of the Gurbānī Sangīt paramparā, who traveled from India for this event. He was accompanied on stage by his students who had performed Sikh kīrtan the previous night, Francesca Cassio, Nirvair Kaur Khalsa, Parminder Singh Bhamra as well as Sat kīrtan Kaur Khalsa. To open his performance, he played a shān on the pakhāwaj as is part of the Sikh kīrtan tradition and to honor the interfaith engagement, sang a maṅgalācaraṇa invocation using the first pada of the Jain ekhibhava stotra. He then demonstrated how the Sikh kīrtan pedagogy teaches rāga movement through sargam exercises and shared ancient and rare shabd-reet compositions to illustrate how musical knowledge can be transmitted over time through the practices of reiteration and repetition. Bhai Baldeep Singh has spent the last thirty years dedicated to learning, sustaining, documenting and reviving the pre-colonial scholarship, pedagogy, and practice of Sikh kīrtan. It is the fruits of his labor that he openly shared through musical, historical and narrative elaborations during his concert at the Jain Center and in his conference paper which developed into the grand opus published in this volume. Bhai Baldeep Singh’s work provides an important bridge between academic and traditional Sikh scholarship and offers a holistic framework for further engagement.

In his auto-ethnographical account on the ‘Memory and Pedagogy of Gurbānī Sangīt’ Bhai Baldeep Singh asks for integrity and exactitude when reviving a pre-colonial Sikh music. As a scholar–musician within a primarily oral tradition, some historians at the conference such as Bob van der Linden have questioned whether Gurbānī Sangīt is distinct from Hindustāni Saṅgīt. Linden and Pashaura Singh also question Bhai Baldeep Singh’s claims to reviving an ‘uncolonized’ Gurbānī Sangīt tradition, that are not merely remnants of his own family’s lineage, but instead are examples of the conjoining streams of pre-colonial musical knowledge (vidyā) that have been transmitted with precision and integrity since the time of the Sikh Gurus. As historians, they ask for material documentation to support Bhai Baldeep Singh’s claims. The lively conversation that ensued at the conference replicated conversations within the emerging academic study of Sikh kīrtan that have occurred between historians, scholars and musicians who debate different claims to authority.Footnote3 As a memory bearer trained in the oral tradition through a pre-colonial pedagogy, it can be argued that Bhai Baldeep Singh is an authoritative primary source.Footnote4 His article included in this volume illustrates the depth of GurSikh knowledge and insight contained in both the material (notations, recordings, instrument designs) and non-material (pedagogy, musicology, oral histories) cultural legacy of the Gurbānī Sangīt paramparā.

In this historic article, Bhai Baldeep Singh shares for the first-time rare findings which he has salvaged and meticulously documented since the 1990s when he traveled far and wide to capture and map any and all remnants of the pre-colonial Sikh kīrtan legacy. Bhai Baldeep Singh argues that Gurbānī Sangīt scholarship is not just about singing a rāga, playing a tāla or copying a composition from another source, but must include the study and analysis of the vidyā that has been transmitted over time. In doing so, his article demonstrates how we can better understand, appreciate and interpret the streams of knowledge that remain from the Guru-Era and the parameters that govern them, including the richness of their expression and grammar. Through my own research, I have come to ascertain that by shifting the current discourse from a competitive comparison of musicians, lineages, and singing styles, toward acknowledging the different spaces that each occupy, it becomes clear that the vidyā of the GurSikh scholarship and pedagogy offers unparalleled insights into a pre-colonial Sikhī that can inform future practice and scholarship.

Nevertheless, there is a resistance within the Sikh community to wholeheartedly accept traditional claims to authority. At the conference, Sikh Studies scholar Charles Townsend in his paper on ‘Ritual Experts’Footnote5 addressed part of the resistance to what he terms ‘expertise’ knowledge because of the Sikh emphasis on egalitarianism. Due to this notion, he questions the appropriateness of terms ‘professional’ and ‘lay’ when referring to Sikh musicians because Sikhs do not distinguish a special ‘class’ or ‘caste’ of people. He cites this as being a potential reason why those career rāgīs and granthīs hired by Gurdwaras in the US make a low level of pay, only $600–700/month (plus room and board) even though many of them have master’s degrees from Indian Universities. Problematically, the diasporic Gurdwaras want ‘professional’ experts, but the pay is commensurate with ‘laity’. In my own paper published in this volume, ‘Engendering the Female Voice in Sikh Devotional Music’ I contend that the reason the rāgī ‘profession’ has become devalued is due in large part to the historic changes in Sikh leadership and identity politics that no longer support nor uphold the integrity of specialized knowledge.

Economic liberalization brought modern notions of egalitarianism that has had the effect of rejecting ‘expertise’ knowledge by catering to individual taste, preference and mass audience appeal. Nevertheless, modernization has created opportunities for equal access to ritual participation and leadership, which can be seen within the gendered access to Jain Stavan and Sikh kīrtan. In her work on Jain stavan singers, Whitney Kelting raises the point that Stavan offers opportunities for females to be free from the duties of their joint families, to have fun, and build prestige. She also notes however, that the ‘women only’ tone is now being lost due to greater male participation, which raises questions about what impact this will have on women-only spaces. Conversely, my paper addresses the male-dominated rāgī ‘profession’ in Sikh kīrtan and how females have been excluded from vidyālā schools that train them, as well as have been barred access and marginalized in religious leadership roles. Bob van der Linden, attributes this to the patriarchal morality that keeps women relegated to the private sphere of home and family.Footnote6

Sikhs in the diaspora, and now in India, have been questioning the androcentric cultural mores which they perceive as conflicting with the egalitarian message of the Sikh Gurus. My paper demonstrates that these diasporic spaces have created opportunities for equal female participation in the public sphere. Agreeing with the shifting landscape of the diaspora, Townsend notes that while ritual experts such as rāgīs and granthī have been designated with the pronoun ‘he’ by the SGPC, there is a pamphlet that has been recently published for Sikhs in the US titled ‘Functions, Duties, and Qualifications of a Granthi’ by Dr. K.S. Dhillon that refers to these ‘experts’ with the pronouns ‘he/she’ designating a diasporic opening for female participation. Still, Townsend notes the lack of ‘professional’ or ‘expert’ Sikh female jathas (singing groups) in the US, though women do dominate the non-expert realm as kīrtan teachers and sevadārs at Gurdwaras. Additionally, Pashaura and Townsend make an important point that within the historic manjī system of Sikh administrative leadership, both the husband and wife were appointed, allowing us to re-asses the historic role of women in Sikh leadership, and question reasons for its change over time. In response to these cases, my own paper affirms that raising the value of Sikh musical knowledge, pedagogy, and practice, and egalitarian access within it, would honor the GurSikh ideals of sovereignty, equality, dignity and respect.

Blurring boundaries

Nikky Guninder Kaur Singh, eminent scholar of Sikh feminisms, spoke on the second day of the conference, highlighting thoughtful correspondences between the ideas previously presented that question the religio-cultural boundaries. Following Sander Hens’ discussion on the influence of sung Bardic vernacular poetry on blurring boundaries in the Jain Sanskrit literary tradition (1206–1526),Footnote7 Nikky Singh acknowledged Guru Nanak’s self-appellation as a bard who blurred boundaries between the dualistic notions of low-high and body–mind. In her paper on the ‘Sensuous Metaphyiscs of the Japji’, she questions the dualistic division between the male-female and masculine-feminine where the Gurus, in their poetic hymns, blur gendered boundaries by taking on the female subjective voice as the bridegroom. In response to my paper’s discussion on gendered boundaries related to the purity-pollution paradigm which excludes females from ritual spheres, Nikky Singh further asks ‘if the female is polluted, why would the Gurus take on the female voice?’ Her paper emphasizes how Guru Nanak’s Japji places value on the senses as a shared language of humanity that is not hierarchical, but brings us beyond the male-centric patriarchal language into a transformation of consciousness that connects us with the whole cosmos. In line with the notion that sensuous aesthetics lead us on an inner journey to the One, Francesca Cassio in her concert performance and paper ‘The Sonic Pilgrimage: Gurbānī Kīrtan as Vehicle of the Spiritual Journey’ demonstrates how the rhythmic, melodic and organizational structure and complex ornamentations of ancient shabd-reet compositions provide a logical and methodical progression to mirror and enhance the meaning of the shabd, guiding the practitioner and listener on a sonic pilgrimage.

The Jain connection to the mystical inner realms through sound was also discussed in Ellen Gough’s paperFootnote8 which addressed how the Jain Bhaktāmara mantra is now being recited as a faith healing practice for karmic benefit. She explains that for the Jains, the efficacy of the Prakrit and Sanskrit mantras is not related to the Hindu belief in the sonic power of Sanskrit as the essence of the cosmos, but instead is linked to Jain karma theory which interprets sonic power emanating from the karmic virtue of the reciter and the affective meaning of the recitation. In Jainism, mantras are used to destroy karma, and in a similar sense, within Sikhi, sonic elements are used to destroy ego-centeredness, the root of karma. In both traditions we see a reciprocal relationship between the practitioner and the musico-poetic practices, that can heal karma and blur dualistic boundaries on an spiritual journey toward wholeness.

Historical confluences

Through the Sikh-Jain project, fascinating historical and literary connections continue to be uncovered, leaving a vast arena for further research. Bob van der Linden offered the only comparative analysis paper, in which he describes a painting found on the Qila Mubarak in Patiala, Punjab that depicts the ‘Arhantha Deva’ the 23rd Jain Thirthankara Parsvanath as well as Maharaja of Karam Singh, along with Vaisnava avatars. Additionally, he notes that Parsvanath and the first Jain Tirthankara Adinath are mentioned in the Dasam Granth, in the composition Ath Rudra Avtar Kathan which discusses the battle between ignorance and wisdom. It honors Parsvanath as a manifestation of divine wisdom, the ‘Rudra Avatar’, which has been linked to the Sikh concept of Hukam, or Divine Will. The Dasam Granth composition Chaubis Avatar also mentions Arihanthas, the Jain term for those souls who have conquered ‘arhat’ ignorance and karma to become pure souls, or Jinas ‘victors’. Respondents Pashaura Singh and Chris Chapple refer to these cases as syncretic devices to incorporate legendary figures into one’s own tradition as well as the predominant Hindu Avatar narrative, to establish their own tradition’s authority and legitimacy within a greater Indic context. Such appropriation is further addressed by Aleksandra Restifo, in her paper that analyzes a thirteenth century Jain play to highlight the complex identity of a Jain minister dedicated to non-violence, who also blurs religio-cultural norms as a warrior who is lauded in battle as avatars of Visnu and deified through a non-jain model of kingship. These examples demonstrate the conversations and connections offered by the Jain-Sikh engagement, and point towards further avenues of investigation.

To close the conference, Chris Chapple remarked on the historical, analytical, cosmological, and musicological symmetry and asymmetry found between the Sikh and Jain traditions. Rather than trying to force symmetry, this Sikh-Jain project offers a unique collaboration to spark new questions and perspectives as we grow the field. Although the tenure of the Jain-Sikh position completed its three-year endowment at LMU in 2018, the research, collaboration, and conversations continue.

Notes of appreciation

I offer my sincere gratitude to those who contributed their voices and support to highlighting these underrepresented traditions and this blossoming field of Jain-Sikh study. This project would not have been possible without the vision and support of Dr. Sulekh and Ravi Jain, Dr. Harvinder and Asha Sahota, and Dr. Nitin and Dr. Kinna Shah. I am especially grateful to my mentor and co-organizer Christopher Chapple who brought this Sikh-Jain position to LMU and graciously guided me through this position with care and respect. I am thankful to my colleagues in the Department of Theological Studies and the faculty and staff at LMU including senior Administrator Faith Sovilla whose logistical guidance ensured the conference was a success, and to former LMU Provost Joseph Hellige, BCLA Dean Robbin Crabtree and Associate Dean Jonathan Rothchild who graciously welcomed this collaboration to LMU. I am thankful to John Jackson and Desirae Zingarelli for supporting the exhibit at William H Hannon Library. I am grateful to the Masters of Yoga Studies program including administrator Sarah Herrington for her gracious support and managing the Yoga Studies graduate assistants, to Sam Calvano for designing our conference material, to Alejandro Godinez and Kija Manhare for investing long hours documenting the conference and concerts on film. I am particularly grateful to Theological Studies graduate assistant Irene Park who helped me to organize and copy edit this publication. Additional thanks go to the students of my Sikhism: Warrior Saints and Hinduism, Jainism, Yoga classes for their participation and engagement at the conference.

I sincerely appreciate the conference speakers and musicians who dedicated countless hours of their energy and time to participate in the conference, concerts, and this publication. Particularly, I appreciate Whitney Kelting for beginning the conference by delivering the Virchand Gandhi Lecture to highlight contemporary Jain scholarship on ‘Jain Temple Building Projects in Maharastra’ and what it means for community, ritual, pilgrimage and cosmology, as well as giving her ethnographic paper ‘Tracking Changes Jain Devotional Singing’ presented in this volume. I am thankful to the contributions of Ellen Gough, Charles Townsend, and Sander Hens who offered invaluable contributions at the conference though they were unable to publish in this volume due to prior commitments. Special thanks go to Adrian Plau for filling this lacuna with his paper that highlights how the musical elements layered onto the Jain Ramayana enhance the meaning and reception of the narrative.

I offer my deepest gratitude to Bhai Baldeep Singh who traveled from India specifically for this conference, who spent countless hours working on his opus published in this volume to preserve the stories, histories, and musicological insights, all the while having to deal with a crisis at his Anād Conservatory in Sultanpur Lodhi due to the careless destruction of heritage artifacts including hundred-years old instruments broken and lost by officers who were attempting to reclaim space at the Qila this past summer 2018. We are honored to publish his paper here in this volume to raise the awareness of the need to preserve any and all historical remnants that remain of the Sikh musical tradition including its intangible assets – memory and pedagogy.

Finally, I am grateful to our respondents Christopher Chapple and Pashaura Singh who offered their thoughtful reflections on the ideas being presented at the conference which led to productive interdisciplinary discussions and provided helpful feedback to strengthen the final versions of the papers presented here in this special issue. Lastly, I owe a debt of gratitude to my advisor Arvind-pal Singh Mandair, who has been a continual source of guidance and support, who believed in the vision of this project and graciously welcomed this Jain-Sikh contribution to Sikh Formations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The Uberoi Foundation for Religious Studies serves to raise awareness of Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism, in an effort to promote understanding, communication, tolerance, and peace. LMU's Mission embraces inter-faith dialogue that moves beyond tolerance to mutual respect and understanding, deepens appreciation of one’s own faith, and creates opportunities for engaging others who share a longing for meaningful lives.

2. To learn more about Jain music see works by Whitney Kelting.

3. In my dissertation, The Renaissance of Sikh Devotional Music: Memory, Identity, Orthopraxy (Citation2014), I argue that the various claims to authenticity are predicated on their relationship to claims to authority, whether they are traditionally, legally, or institutionally sanctioned. Gerald Bruns in his book ‘Hermeneutics Ancient and Modern’ (Citation1992) asserts that ‘Any reflection on tradition entails a corresponding need to work through the nature of authority.’ Working through Gadamer and Levinas he attempts to affirm a freedom from coercive authority that uses its power to rule. In contradistinction to an authority of rule, he offers the notion of an authority of claim which ‘is not imperialist. It cannot be institutionalized, that is, it is not a claim whose power lies in its self-justification … this claim demands not obedience but openness, acknowledgement, and acceptance of what is singular and otherwise.’ (Bruns 211–12) Here we glean a sense of the paramparā’s authority of claim as a connection to an authoritative voice that is part of an ever-flowing stream of knowledge transmission that resists the authority of rule which coerces through power and force through institutional bodies that create standardized notions. (211) It is due to these differing claims to authority, that we see contemporary debates occurring between historians, musicians, scholars and memory bearers regarding authenticity. In my article ‘Engendering the Female Voice in Sikh Devotional Music’ published in this volume, I use this understanding to argue that the SGPC is an institutional body whose authority of rule has barred females from participating in certain sevas in the inner sanctum of the Harimandir Sahib, such as kīrtan and ishnān, due to their own stagnant interpretation of the maryādā that does not allow it to evolve over time. Bhai Baldeep Singh argues that the GurSikh knowledge is a flowing stream that emanates from the SatGuru, through the Sikh Gurus, Bhagats, and Sikhs without claiming exclusivity to any one caste, creed, gender, language, or nationality.

4. Bhai Baldeep Singh is a reservoir of knowledge that has been passed down through his family since the sixteenth century, as well as through his teachers including master musician Bhai Arjan Singh Taraṅgaṛ, born at the turn of the twentieth century, who carried the Sikh streams of musical knowledge into the post-colonial era. Bhai Baldeep Singh is the 13th generation descendent of a Gurbānī kīrtan lineage that is traced back to Bhai Sādhāraṇ Sembhī, a Sikh of Guru Nanak and classmate of the second guru, Guru Arjan Dev, and who built the Baoli at Goindwal. Bhai Baldeep Singh’s great grandfather Bhai Narain Singh was Bhai Jwala Singh’s eldest brother (and eldest uncle to Bhai Avtar Singh and Bhai Gurcharan Singh). As the eldest brother of the family, he maintained the ancestral knowledge and histories which he passed on to his family. In 1987, when Bhai Baldeep Singh began studying with Bhai Avtar and Bhai Gurcharan Singh, they said they could answer musical questions, but referred him to his grandmother, Bibi Sant Kaur (also sister in law of Bhai Gurcharan Singh to whom her youngest sister was married) for family histories. As the eldest of all the siblings and spouses, she recalled that Baba Jwala Singh referred to his father as the 9th and himself along with his eldest brother Narain Singh, as the 10th generation exponents. Baba Jwala Singh was part of the Gurdwara freedom movement and demonstrated great resistance to British colonial control. He was jailed for months and the entire family household ransacked monthly by British officers who confiscated important historical artifacts, documents, diaries and even musical instruments. In the late 1980s Bhai Baldeep Singh undertook painstaking research to excavate these memories, genealogies and oral histories from elders within and beyond the family as he became aware of the repertoire and narratives his granduncles did not possess. His paper published in this volume demonstrates the complex nature of retrieving marginalized histories and harnessing living memory to revive near extinct musical knowledge. Because Bhai Baldeep Singh was trained in the oral tradition as a historian and memory bearer of the Gurbānī Sangīt paramparā, he argues it offers an ‘uncolonized pedagogy’ when studied, transmitted, and practiced with integrity and exactitude.

It is rare to find someone who is unrelenting in their quest for historic and semantic precision in the preservation of the Sikh Guru’s musical tradition. He unfailingly and unflinchingly critiques those whom he sees as distorting and damaging the integrity of the knowledge from the Guru-Era (GurSikh vidyā), as well as those who misrepresent or have erred in their transmission of it, regardless of familial ties. It is also rare to find a musician-scholar well versed in the language of the tradition who can communicate that scholarship by translating the concepts into English, for both lay and academic audiences. This makes Bhai Baldeep Singh’s article extraordinary, as it offers critical analysis of extant musicality, retrieves important musicological insights, and enhances the field with grammatical interventions.

5. Abstract of the paper presented by Charles Townsend at the conference, not published in this volume: ‘Experts’ in the Sikh Tradition from the Gurus to the United States: Sacred Musicians, Keepers and Performers of the Scripture, Preachers, and Knowledge-bearers.

This presentation will profile what I am referring to as the ‘ritual experts’ of the Sikh tradition: people who perform music, major religious rituals, practices, duties, and functions in Sikh communities and lead others in these practices, and who have specialized knowledge and training to do so. Currently, in Sikh communities around the world, the two main roles of religious leadership and ‘ritual expertise’ are both musical in nature: that of the granthī (one who recites from, tends to, and cares for the primary Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib), and the rāgī (a person who musically performs the hymns of Guru Granth Sahib). I will discuss roles of leadership, authority, and ‘ritual expertise’ throughout the history of the Sikh tradition and then present a portrait of how such roles are currently understood and performed in Sikh communities in the diaspora drawing from my personal interviews with granthīs and rāgīs in the United States, and, finally, I will discuss issues surrounding the current and future contours of leadership within American Sikh communities, drawing comparisons with other immigrant groups in American history.

6. Van der Linden in his article included in this volume ‘Songs to the Jinas and of the Gurus: Historical Comparisons between Jain and Sikh Devotional Music’offers insight into the negotiation of male- female, professional-lay roles in Jain Stavan and Sikh kīrtan: ‘Dissimilar from the Sikh case, Jain bhaktī does not have a tradition of professional performers. Although some male Jain professional musicians do exist, Jain devotional music is largely performed by amateur women in relatively institutionalized hymn singing groups, and partly for this reason also it remains based on regional folk music genres.’ He cites Whitney Kelting’s work on women’s roles in Jain Stavan to state that ‘it remains interesting to mention that Jain recordings are dominantly sung by men and in an art music style, which includes the use of a drone and tabla for example, because they almost never sing solo in temples due to the existing idea that female voices are more auspicious.’ His paper also addresses the private-public divide between male and female singers, ‘In addition, it remains typical that female Jain hymn singing groups generally perform during liturgical ceremonies, while male groups more do so during festive and public ones. According to Whitney Kelting, the use of microphones in the making of Jain music is also very male-oriented, as they are often turned off when women perform.’ The male domination of the public sphere is also raised in my paper, where I offer examples of Sikh women who have experienced their microphones being turned off when singing in the Gurdwara.

7. Abstract of the paper presented by Sander Hens at the conference, not published in this volume: Criticism, ambivalence, and irony in Jaina Sanskrit narratives of the Chauhan kings and the influence of bardic literature.

This paper largely deals with revealing Nayacandra Sūri’s ironic attitude in his Hammīramahākāvya (15th c., ‘epic on Hammīra’), in which the author – contrary to scholarly belief – does not really intend to praise the Chauhan kings. Supplementing the analysis of this text with a thorough contextualization, this paper touches on questions about interactions between bardic, vernacular poetry and Jaina Sanskrit narratives of the Chauhan kings.

8. Abstract of the paper presented by Ellen Gough at the conference, not published in this volume: Karmic Consequences and the Healing Power of the Bhaktāmara Stotra.

This paper examines the philosophical foundations of a present-day interpretation of a single Prakrit praise: ṇamo akkhīṇamahāṇasāṇaṃ, ‘praise to those who have an inexhaustible kitchen.’ Today, many Digambara Jains believe that this praise, when recited along with a mantra and the 45th verse of the Sanskrit praise poem the Bhaktāmara Stotra, has the power to cure incurable diseases such as cancer. But what is the philosophy behind such claims? This paper answers this question by looking at the history of this praise and examining the only commentary on it, Vīrasena’s the Dhavalā. The Dhavalā provides the karma philosophy behind the healing power of sound, arguing that for Jains, unlike in many Hindu traditions, the power of sound does not come from the language of the recitation – Sanskrit’s role as the essence of the cosmos – but instead comes from the virtue of the reciter and the meaning of the recitation.

References

- Bruns, Gerald. 1992. Hermeneutics Ancient and Modern. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Khalsa, Nirinjan Kaur. 2012. “Gurbani Kirtan Renaissance: Reviving Musical Memory, Reforming Sikh Identity.” Sikh Formations: Religion, Culture, Theory 8 (2): 199–229. doi.org/10.1080/17448727.2012.720751.

- Khalsa, Nirinjan Kaur. 2014. “Renaissance of Sikh Devotional Music: Memory, Identity, Orthopraxy.” Ph.D Diss. University of Michigan. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/107325.