ABSTRACT

This article discusses the application of Social Network Analysis (SNA) to corporate networks in a long-term and historical perspective. Starting with the basic concepts of corporate networks and the main research themes it has addressed in business history, the article then introduces how historical quantitative archival data can be played with and turned into excel data suitable for the study of social networks by using software such as UCINET. The article then provides two examples of how this methodology has been used at both the macro and the micro levels: national corporate networks in Argentina and Chile from 1900 to 2010 and the social club memberships, partnership ties, and interlocking directorates of J.P. Morgan & Co. in the early twentieth century. Finally, the article discusses new perspectives for the application of SNA in business history.

1. Introduction

In this essay, we discuss the application of Social Network Analysis (SNA) to corporate networks from a long-term and historical perspective. Starting with the basic concepts of corporate networks and the main research themes it has addressed in business history, we then introduce how historical quantitative archival data can be played with and turned into excel data suitable for the study of social networks using software such as UCINET. Finally, we provide two examples of how this methodology has been used at both the macro and the micro levels: national corporate networks in Argentina and Chile from 1900 to 2010 and the social club memberships, partnership ties, and interlocking directorates of J.P. Morgan & Co. in the early twentieth century. These case studies elucidate how SNA can unveil new connections and spark creative thinking to play with new research perspectives from the use of traditional sources such as lists of firms and their directors. We will also demonstrate how SNA allows researchers to ask and answer questions in a more systematic way than it had previously been possible but in surprising ways to reveal the absence of ties.

2. Basic concepts and main research questions

The biggest contribution of SNA to business history has been to shed new light – from a long-term perspective – on corporate network structures, their evolution and determinants as well as on the organizational outcomes of the firms involved (David and Westerhuis Citation2014; Cordova-Espinoza Citation2018).

Corporate networks represent a ‘non-visible’ structural institution in a society that enables and inhibits the decisions of shareholders and directors. These ‘informal mechanisms’ are a relevant element in the study of corporate governance. The two most studied networks are shareholders networks (Kogut Citation2012) and directors networks (David and Westerhuis Citation2014). We focus on the latter, which are commonly referred to as Interlocking Directorates (IDs). An interlock is the link formed between two firms when a person is a director of both. IDs constitute the structure (or at least part of it), in which economic life is embedded (Granovetter Citation2005). In other words, IDs are a ‘transcendent network’ where each actor assimilates and transmits the influence of innumerable other actors, both proximate and remote (Useem Citation1984).

A distinction can be made between those who claim that IDs are irrelevant and those who think they are important for corporate control analysis. Among the former, there are the theorists of managerial control of the firm: they argue that control is exercised by management inside the firm and the board of directors works only as an organ of representation and as an image for the market (Koenig, Gogel, and Sonquist Citation1979; Silva et al. Citation2021).

Among the latter, two main approaches can be identified. On the one hand, there are those who see IDs as a control mechanism. This view dates back to Hilferding’s (Citation1968 [1910]) theory of ‘finance capital’ and was pushed a step further by Kotz’s (Citation1978) ‘bank control model’. According to this approach, control of credit flows and, more rarely, part of firm’s equity enables banks to determine firms’ strategy. IDs are a major instrument to enforce this control through the presence of bank fiduciaries on company boards. Mintz and Schwarz (Citation1985) argued that IDs are instruments for banks to influence industrial firms with discretion, a perspective, which was recently re-asserted by Colvin (Citation2014). On the other hand, there are those who see IDs as a coordination and communication mechanism driven by convergence of interests. In particular, resource dependence models argue that restrictions on resources, information or markets stimulate firms to create business groups, whose presence can be detected through the analysis of IDs. The hypothesis is that firms use IDs as means to co-opt or absorb, partially or completely, other organizations with which they are interdependent (Hillman, Withers, and Collins Citation2009). In the case of the bank–industry relationship, IDs are not an instrument for banks to exert control over industry but are driven by a convergence of interests between banks and industrial firms (Haunschild and Beckman Citation1998), a point emphasized, in the business history, literature by Fohlin (2007, 2012). Another strand of literature analyzes IDs from the perspective of links between individuals. Here, the network of IDs is considered an indication of the cohesion of the corporate elite (Mizruchi Citation1996; Carroll Citation2010). A dense network is an expression of the cohesion of the elite and its capability to act in a coordinated way. Dense networks erect barriers against free riding, as network members have the capability to monitor and sanction each other. Networks can also impose a certain code of ethics amongst the members of the elite. As a result, in largely held joint stock companies, IDs can replace ownership as a mechanism of control (Windolf Citation2014). Most connected interlockers constitute an ‘inner circle’ with higher degree of social cohesion and political influence (Useem Citation1984).

These different perspectives are mutually exclusive as each of them attributes the existence of IDs to only one reason, justified by the theory. Opposed to these views, a pluralistic interpretation of IDs was advanced, which emphasizes not the reason but the plurality of modalities in which the phenomenon of IDs manifests itself. The underlying idea is that ID analysis cannot verify any theory ex ante but can be very useful in the understanding of a wide range of themes in business history and in the analysis of the structure of corporate systems (Granovetter Citation1993).

An ID can simultaneously influence the flow of knowledge of opportunities and the capability to act by access to different resources, lower information and transaction costs, give privileged access to markets, and impact on firm status, reputation, and power. A much-debated question is the relationship between IDs and firm performance. Evidence in this respect is inconclusive and it is not sure that more interlocked firms are also more profitable. This can be a reflection of uncertainty over the causal order of the interlock-profitability association. On the one hand, the desire of more reputable directors to join the boards of best performing firms and access to resources through IDs can be said to improve firm performance; on the other hand, banks often send their fiduciaries to monitor bad performing firms (Mizruchi Citation1996).

The use of SNA in business history has allowed researchers to open new perspectives in the analysis of systems of actors wherein economic action is embedded. The focus on IDs and corporate networks has revealed to be particularly useful in noticing new – and sometimes surprising – connections among firms, financial institutions, economic elites and the state. In turn, these have triggered new interpretations of the structures of coordination, control and power in capitalist societies (Hall & Soskice Citation2001; David and Westerhuis Citation2014; Sapinski and Carroll Citation2018).

The pioneering project ‘They rule.net’, an interactive visualization of the interlocking directories of the largest U.S. companies, for example, aims to make visible some of the power relationships of the U.S. ruling class. The goal is to play with, browse and generate networks of influence of the boards of some of the most powerful individuals and companies in America. ‘They Rule’ can visualize something abstract like the connections between individuals and offers a materiality to that power (by means of icons with name and surname). Additionally, it is a tool that stimulates more questions about the conflicting interests of powerful business leaders.

3. Sources, databases, methodologies and disciplines: Interlocking directorates in Argentina and Chile from 1900 to 2010

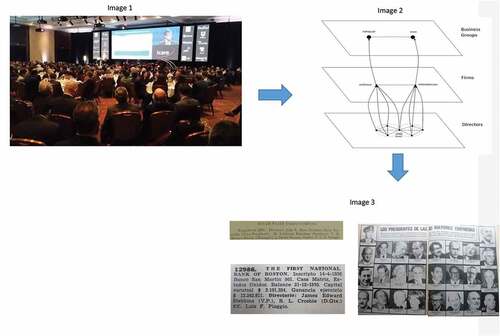

The project on Argentina and Chile’s Corporate Networks began with the observation of business elite in Chile at the annual meeting of a well-known business association (see image 1 in Appendix). Participation in this meeting was serendipitous and led to the following questions: How did connections created through associations, which seemed to assist in the creation of cohesion between businesspeople, affect the connections among their firms? Is there overlap between the cohesive business elite and a connected structure of firms and business groups? Image 2 (AppendixAppendix) reveals the various levels of analysis that we addressed in studying these research questions, not previously explored, about the structure and evolution of inter-firm relationships in Argentina and Chile.

As scholars trained in social networks methodology, we began to play with the idea of collecting network data and applying social network analysis to explain this social phenomenon. We decided to focus on the years 1900–2010, a long-time span which covers the entire twentieth century and the first decade of the new millennium (Salvaj and Lluch Citation2012; Lluch and Salvaj Citation2014; Salvaj Citation2013). We relied on historical data sources that had never been used before in SNA and ID research (see image 3 in AppendixAppendix), such as the Yearbooks of Argentina 1923, 1937; Limited Companies Guide of 1944, 1954, 1970; Official Gazette of Argentina 1990, 2000 or the annual reports of the companies. Additionally, we relied on historical data from numerous libraries and physical repositories such as Library of the Buenos Aires Stock Exchange, General Inspection of Justice, Central Bank of Argentina and Chile, Bank of Buenos Aires, Library of the Ministry of Economy of Argentina and Chile and the Official Gazette of Santa Fe (see Lluch and Salvaj Citation2014 for more information).

As data collection and analysis evolved, we discovered new connections shaping the ID networks of the two countries. Foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) and Business Groups (BGs) emerged as highly relevant and central players, whereas banks, which had played a pivotal role in shaping these networks in Europe and North America, were much less relevant in Argentina and Chile. These findings led us to ask new questions: What led MNEs and BGs to occupy such a central position in the two countries? How do BGs relate to each other over time? What kind of relationships do we observe among private BGs, MNEs and the state? (Lluch and Salvaj Citation2014; Lluch, Salvaj, and Barbero Citation2014; Salvaj and Couyoumdjian Citation2016; Bucheli and Salvaj Citation2014, Citation2018). For the purpose of our research, we defined BGs as legally independent firms, operating in multiple (often unrelated) industries, linked by persistent formal (e.g. equity) and informal (e.g. family, common directors) ties.

The process of data collection and database construction deserves special attention. To acquire the historical data, we relied on several older, meaning traditional, historical sources (see image 3). The identification and subsequent conversion into digital files created significant value because it concentrated information that was scattered in many physical repositories and libraries spread throughout Argentina and Chile. Our project received financial support from the Chilean government, which made it possible to hire assistants to collect and transform the data from physical repositories into digital files. Thus, when junior researchers consider embarking on a project of these dimensions, it is important to keep in mind the need to access grants to support this type of research.

Before collecting the data on board members, we had to develop rankings of the largest firms up to the 1970s. For recent years (from the 1980s onwards), we used rankings prepared by Revista Mercado, an Argentinean business magazine, and America Economia.Footnote1 Historical rankings were another unique contribution of the project. We created, for the first time, rankings to identify the largest companies in each country from 1900 to 1980 (for every 10 years). We used company capital and/or sales as proxy of company size, depending on data availability for each year. Based on the rankings, we collected information on board members of the 25 largest banks and the 100 largest non-financial companies of each country. Our dataset is neither a time series nor a panel. It is based on benchmarks taken about 10 years apart from each other and that cover a time span longer than a century, from 1900 to 2010.

One of the challenges of collecting data for such a long interval of time is periodization. Our decision to collect data every 10 years was influenced by the guidelines of David and Westerhuis’s (Citation2014) international corporate networks project and served to compare Argentina and Chile more accurately with the other countries analyzed in the project. This periodization could mean a limitation and at the same time an opportunity to work on future corporate network projects collecting data with shorter periods of time, e.g. 5 years. This would partly solve problems such as the death of especially connected directors who might take their network connections with them and that our 10-year periodization does not allow us to identify. Based on these data we calculated network statistics that answered our research questions. We calculated the most commonly used measures in SNA (David and Westerhuis Citation2014). In terms of tools, we used UCINET to analyze the data and calculate all the network measures and Gephi to build graphs.

The process was rewarding. We created a unique dataset that approached business networks in Argentina and Chile from different angles and resulted in several academic publications. We implemented interdisciplinary work with business historians, sociologists, management scholars, political and computer scientists. This interdisciplinary approach provided plausible interpretations of the phenomenon of interest. The whole process led us to qualitative historical analysis and study how structural breaks or external shocks impact these networks, affecting the dynamics operating within the corporate elites of Argentina and Chile. Our main finding reveals that, in the long run, the Argentinean corporate network disentangled into a highly fragmented one, but that this was not the case of Chile. In Chile, we had a very stable and cohesive network (Salvaj and Lluch Citation2012; Salvaj Citation2013). In Argentina, we observe in the first half of the century a connected network, but from the 1950s onwards it began to fragment, and the decline continued until 2000, when most companies became isolated. We argue that the historical path followed by corporate networks was mainly driven by changes in the economic structure of the local capitalism, the institutional ruptures and political instability of the country and by the dynamics operating at the internal cycle of corporate leaders in Argentina (Salvaj and Lluch Citation2012; Lluch and Salvaj Citation2014; Salvaj Citation2013).

4. Sources, databases and methodology: the networks of J.P. Morgan & Co. from 1895 to 1940

In the literature on SNA, IDs are considered affiliation ties or ties that represent shared characteristics between different nodes in a network. The term ‘affiliations’ usually refers to membership or participation data, such as when we have data on which actors have participated in which events. These ties are significant because often the co-membership in groups or events is an indicator of an underlying social tie. An affiliation tie can also represent an available path between nodes without having to show that path was actually taken (Borgatti and Halgin Citation2011).

One of the best known studies of affiliation ties is Davis, Gardner, and Gardner (Citation1941) that analyzed the overlapping participation of Southern society women and the way in which racism was embedded in the social and economic organizations of the American South in the 1930s. Another landmark study is Padgett & Ansell (Citation1993) on the centralization of political parties and elite networks that underlay the birth of the Renaissance state of Florence in the fifteenth century. Building on these and other studies (Dye Citation1976; Domhoff Citation2006), we engaged in an in-depth case analysis of the banking firm of J.P. Morgan & Co., focusing on the formation of their affiliation ties within the American financial community between 1895 and 1940.

The study of the Morgans’ economic ties has been extensively investigated in both economics and sociology (Roy Citation1983; Simon Citation1988; De Long Citation1991, Citation1992; Hannah Citation2007). While the formal organization of their social ties has been less rigorously documented, the social nature of their business is well known. Private investment bankers were generally organized as unlimited liability partnerships, which meant that their financial data was not public. In lieu of this information, clients and investors relied upon monitoring the individual and social behavior of the partners as signals of their creditability and solvency. For this reason, the personal reputations of private bankers were extremely important as a signal to outsiders with regards the economic stability of their firm (Pak Citation2013b).

Though qualitative data persuasively argue that social networks and social ties were important, our case study sets out to understand which social ties were the most relevant to study the internal organization of the Morgan firm and also their relationships to other firms. We combined the study of the firm’s economic ties, specifically the partners’ percentage capital in the firm, their IDs, and their syndicate partnerships, with the partners’ memberships in social clubs to test whether social clubs were an appropriate measure to study their economic network. Our findings demonstrated that they were. What makes the findings surprising is that they can also be useful to understand how social ties are important when they are absent.

We first ran a correlation between the Morgan partners’ social club membership with the percentage capital that a Morgan partner had in the firm. A partner’s percentage capital in the firm was an indicator of how central a partner was to the firm. The more percentage capital or liable the partner was for the profits and losses of the firm, the more central he was to the operation of the firm. This was distinct from the amount of capital that a partner had invested in the firm, even though the two measures were often aligned, meaning the partner with the greatest investment was also the most central to the firm. Using a longitudinal fixed effect time series analysis, we found that Morgan partners active in core social club circles with other partners were more likely to increase their capital ownership in the firm in the following five-year period. It is also highly likely that more ambitious partners, who wanted to increase their capital ownership and their status in the bank, were more active in social clubs though it is difficult to identify what came first in correlated data. Combined with the qualitative study of the records of the partners, we were able to conclude, however, that social clubs were an appropriate measure for studying the Morgan partners’ social relationships as economic actors

After we determined that social clubs were a useful measure for determining a partner’s position within the firm, we turned to the question of whether it was a useful measure for analyzing the firm’s external relationships – to clients and to syndicate partners, who could be other banks or individuals. To mention just our study of the correlation between social club membership and the participation that firms were given in the Morgan syndicates, we identified a relevant group of firms within the banking community by looking at the directors and partners of the top 18 national banking institutions as identified by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912 during their investigation on the concentration of money power or the Money Trust investigation (also called the Pujo hearings, 1912–1913. Hereafter called the ‘Pujo dataset’). Combining the Pujo dataset on IDs with the amount of syndicate participation of each bank in the Morgan Banks from 1894 to 1912, we then correlated these data with the social club memberships of the Pujo bankers. We found that the Morgan's tended to work more with participants with whom they had closer social ties, meaning that those bankers with more board overlaps and social club overlaps had greater syndicate participation in the Morgan's deals than those who did not. Thus, we concluded that social club memberships were also an appropriate measure to study the social relations between the Morgans and persons external to the firm.

The findings that social ties were important to private bankers may seem par for the course, but the value of SNA is that these findings also allowed us to identify more unconventional questions, such as how private bankers established trust in the absence of social ties. In other words, the perhaps unexpected contribution of SNA to historical research is the way in which it can allow one to discover questions and issues that might otherwise be invisible and therefore taken for granted as the norm. For instance, the Morgans’ private banking networks have been studied by many scholars, including Vincent Carosso, a historian who knew the Morgans’ business so well that his own papers are now housed at the Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum. We know that Carosso considered the Morgans’ social clubs to be important because he took notes about them in his own handwriting on yellow pads of paper, which have been preserved for posterity. He surely would have known that the Morgan partners had social clubs in common with WASP bankers like First National Bank’s George Baker and not German-Jewish-American bankers like Jacob and Mortimer Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. Carosso’s analysis, however, largely ends there. He concluded that the lack of social ties between the Morgans and the Schiffs were not important to their financial relationship because evidence of their financial relationship seemed so strong. Without the assistance of SNA (or even excel) to perform a systematic analysis of syndicate AND social club ties, one could not see, as Pak was able to confirm, that the Morgans and the Schiffs did in fact work together but to such an extent that made their social distance seem even more significant than previously understood. Thus, rather than assuming that the distance was not important, the findings of the absence of ties and the distance between nodes indicate that one should then be able to explain how the Morgans and the Schiffs were able to work together in a business as personal as banking despite the absence of social ties. Even if SNA does not provide the answer to the question, what it can do is to help researchers verify the existence of an issue that previous literature had not considered important enough to study. That issue is the formation of the social norm itself, which can be made visible (if not explained) through the systematic study of historical data with SNA. In other words, SNA research can also stimulate theoretical analysis of norms, a finding that could be useful for many other studies, particularly those that look at marginalized groups or subjects that fall outside those norms (Pak Citation2013a).

5. New directions for future research

What are the new directions and applications of SNA in business history in a context where more and more digitalized archives will become available? As shown, business historians can use SNA in a creative and playful way to engage with more recent debates and provide new original and plausible interpretations. Recently, one of the most outstanding results of research in this field has been to demonstrate the weakening of national corporate networks nearly everywhere in the world since the 1980s and the advent of globalization (David and Westerhuis Citation2014). But what are the reasons for this? Are they the result of corporate governance reforms explicitly aimed at limiting the size of boards of directors, and the number of directorships each director can hold? Can they be because a change in banks’ strategy that chose to disengage from industrial firms as banks moved away from traditional lending toward fee-based forms of business, i.e. investment banking? What are the other factors contingent on the institutional setting of individual countries? And, more significantly, is this decline in cohesion leading to the end of national corporate networks and to a loss of a corporate elite (Mizruchi Citation2013) or to their recomposition into ‘small worlds’ (Kogut Citation2012)?

Other possible areas of investigation include the emergence of transnational networks (Heemskerk, Fennema, and Carroll Citation2016; Murray Citation2016), and the role of regional networks. For example, Vasta et al. (Citation2017) and Rinaldi and Spadavecchia (Citation2021) found that networks centered on local banks that link these to local industrial firms are a long-term structural trait of Italian capitalism. The disentangling of IDs directorates should also lead to awareness of the study of other networks than those of directors, i.e. shareholders’ networks, networks that are created by joint membership of think-tanks, policy-planning group, university board, employers’ associations, philanthropic associations, or, in the EU, the European Table of Industrialists (Sapinski and Carroll Citation2018).

As the technology for the study of quantitative analysis advances, other future avenues can emerge if and when SNA is combined with other methodologies, for example, QCA analysis. Margaretic, Salvaj, and Diaz (Citation2023) have recently explored the impact of (de)globalization and macroeconomic configuration on IDs measures from different countries in the long term. The simulation, ‘They Rule’, mentioned previously, has one weakness in that it is not a real-time representation of IDs. But future projects based on other countries could rely on information in real time, as the formation of company directories is constantly changing, and expanded to include simulations of the power networks of politicians, entrepreneurs or knowledge networks.

Ultimately, as we have shown, SNA can be used to engage with the historical data and also test, rather than assume, that our questions or our units of analysis are relevant for the historical actors, times and places that we study. This is an insight that is worth remembering with or without the assistance of any quantitative tool or technology, but which SNA makes possible to see when we, as researchers, are open and willing to experiment to unlock the information that historical records already contain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alberto Rinaldi

Alberto Rinaldi is Associate Professor of Economic History at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy. He got a Ph.D. in Economic and Social History from Bocconi University, Milan. He was a visiting scholar at the Centre for International Business History, University of Reading, UK. He received grants from the Italian Ministry of University. He has researched extensively on interlocking directorates, corporate governance, industrial districts and female entreprenurship in Italy. His publications have appeared in leading international journals.

Erica Salvaj

Erica Salvaj is Professor of General Management and Strategy and Research Director at the School of Business and Economics at Universidad del Desarrollo (UDD), Chile and Visiting Scholar at Universidad de San Andres, Argentina. Her primary fields of research are strategy, leadership, social networks, corporate governance, international business, gender and business history. She completed her Ph.D. in Business Administration at IESE Business School, Barcelona, was GCEE Fellow at Babson College and has received fellowships and research grants from the Argentinean and Chilean National Commissions for Scientific and Technological Research. She has been awarded with the fellowship “Alfred Chandler” from Harvard Business School and the Australia-APEC Women in Research Fellowship. Her publications have appeared in leading international journals.

Susie J. Pak

Susie J. Pak is an Associate Professor in the Department of History at St. John's University, New York. A graduate of Dartmouth College and Cornell University, she is the author of Gentlemen Bankers: The World of J.P. Morgan (Harvard University Press, 2013). Pak has served as a Trustee of the Business History Conference, and she serves as co-chair of the Columbia University Economic History Seminar and as co-editor of the Global Enterprise series of Cambridge University Press. She is a member of the Editorial Advisory Boards of Business History Review, Financial History, and Connections, the journal of the International Network of Social Network Analysis. Her works have appeared in leading international journals.

Daniel S. Halgin

Daniel S. halgin is Associate Professor of Management at the University of Kentucky and a member of the LINKS Center for Social Network Analysis. He is also co-Editor in Chief of Connections and director of the Intra-Organizational Networks Conference. He received his Ph.D. from the Management and Organizations Department at Boston College. His research interests include social networks and social cognition in organizations and markets. His works have appeared in leading international journals.

Notes

1. Revista Mercado publishes the traditional ranking of the companies with the highest turnover in Argentina; it has been published for 25 years, AméricaEconomía is a business magazine that covers Latin America in Spanish and Portuguese. In December 1989, the 300 Largest Companies in Latin America was published, which a year later would become the special edition of the 500, an analysis of the Latin American economy based on its 500 largest companies, which would be a regular ranking of publication ever since.

References

- Borgatti, S., and D. Halgin. 2011. “Analyzing Affiliation Networks.” In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, edited by J. Scott and P. J. Carrington, 417–433. New York: Sage.

- Bucheli, M., and E. Salvaj. 2014. “Adaptation Strategies of Multinational Corporations, State-Owned Enterprises, and Domestic Business Groups to Economic and Political Transitions: A Network Analysis of the Chilean Telecommunications Sector, 1958–2005.” Enterprise & Society 15 (3): 534–576. doi:10.1093/es/khu025.

- Bucheli, M., and E. Salvaj. 2018. “Political Connections, the Liability of Foreignness, and Legitimacy: A Business Historical Analysis of multinationals’ Strategies in Chile.” Global Strategy Journal 8 (3): 399–420. doi:10.1002/gsj.1195.

- Carroll, W. K. 2010. The Making of a Transnational Capitalist Class: Corporate Power in the 21st. Century. New York: Zed Books.

- Colvin, C. L. 2014. “Interlocking directorates and conflicts of interests: the Rotterdamsche Bankvereeniging, Muller & Co. and tnhe Dutch financial crisis of the 1920s.“ Business History 56 (2): 135–160. doi:10.1080/00076791.2013.771342.

- Cordova-Espinoza, M. I. 2018. “The Evolution of Interlocking Directorates Studies – a Global Trend Perspective.” AD-Minister 33: 85–112.

- David, T., and G. Westerhuis, edited by. 2014. The Power of Corporate Networks. A Comparative and Historical Perspective. New York-London: Routledge.

- Davis, A., B. B. Gardner, and M. R. Gardner. 1941. Deep South: A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- De Long, J. B. 1991. “Did J.P. Morgan’s Men Add Value? An Economist’s Perspective on Financial Capitalism.” In Inside the Business Enterprise: Historical Perspectives on the Use of Information, edited by P. Temin, 205–249. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- De Long, J. B. 1992. “J.P. Morgan and His Money Trust.” The Wilson Quarterly 16 (4): 16–30.

- Domhoff, G. W. 2006. Who Rules America? Power, Politics & Social Change. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Dye, T. R. 1976. Who’s Running America? Institutional Leadership in the United States. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Granovetter, M. 1993. “The Nature of Economic Relationship.” In Explorations in Economic Sociology, edited by R. Swedberg, 28–66. New York: Sage.

- Granovetter, M. 2005. “The Impact of Social Structure on Economic Outcomes.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19 (1): 33–50. doi:10.1257/0895330053147958.

- Hall, P. A., and D. Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism. The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hannah, L. 2007 What Did Morgan’s Men Really Do?. University of Tokyo, Dept. of Economics, Working Paper, http://www.cirje.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/research/dp/2007/2007cf465.pdf

- Haunschild, P. R., and C. M. Beckman. 1998. “When Do Interlocks Matter? Alternate Sources of Information and Interlock Influence.” Administrative Science Quarterly 43 (4): 815–844. doi:10.2307/2393617.

- Heemskerk, E. M., M. Fennema, and W. K. Carroll. 2016. “The Global Corporate Elite After the Financial Crisis: Evidence from the Transnational Network of Interlocking Directorates.” Global Networks 16 (1): 68–88. doi:10.1111/glob.12098.

- Hilferding, R. [1910] 1968. Das Finanzkapital. Eine Studie über die jüngste Entwicklung des Kapitalismus. Frankfurt am Main: Europäische Verlagsanstalt.

- Hillman, A. J., M. C. Withers, and B. J. Collins. 2009. “Resource Dependence Theory: A Review.” Journal of Management 35 (6): 1404–1427. doi:10.1177/0149206309343469.

- Koenig, T., R. Gogel, and J. Sonquist. 1979. “Models of the Significance of Interlocking Corporate Directorates.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 38 (2): 173–186. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1979.tb02877.x.

- Kogut, B., edited by. 2012. The Small World of Corporate Governance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kotz, D. 1978. Bank Control of Large Corporations in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lluch, A., and E. Salvaj. 2014. “Longitudinal Study of Interlocking Directorates in Argentina and Foreign Firms’ Integration into Local Capitalism (1923–2000).” In The Power of Corporate Networks. A Comparative and Historical Perspective, edited by T. David and G. Westerhuis, 257–275. New York-London: Routledge.

- Lluch, A., E. Salvaj, and M. I. Barbero. 2014. “Corporate Networks and Business Groups in Argentina in the Early 1970s.” Australian Economic History Review 54 (2): 183–208. doi:10.1111/aehr.12044.

- Margaretic, P., E. Salvaj, and J. Diaz 2023. Corporate Networks, (de)globalization, and Macroeconomic Configurations: A Historical Approach. ( Work in progress)

- Mintz, B., and M. Schwarz. 1985. The Power Structure of American Business. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mizruchi, M. S. 1996. “What Do Interlocks Do? An Analysis, Critique, and Assessment of Research on Interlocking Directorates.” American Review of Sociology 22 (1): 271–298. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.271.

- Mizruchi, M. S. 2013. The Fracturing of the American Corporate Elite. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Murray, J. 2016. Occupied by Wall Street: Finance Capital at the Center of the Policy Network, Paper Presented at “Who Rules America? Who Rules the World? Three Generations of Power Structure Research”, Society for the Study of Social Problems Annual Conference, Seattle, WA, August 2016.

- Padgett, J. F., and C. K. Ansell. 1993. “Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400-1434.” The American Journal of Sociology 98 (6): 1259–1319. doi:10.1086/230190.

- Pak, S. J. 2013a. Gentlemen Bankers: The World of J.P. Morgan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pak, S. J. 2013b. “Reputation and Social Ties: J.P. Morgan & Co. and Private Investment Banking.” Business History Review 87 (4): 702–728. doi:10.1017/S0007680513001104.

- Rinaldi, A., and A. Spadavecchia. 2021. “The Banking-Industry Relationship in Italy: Large National Banks and Small Local Banks Compared (1913-1936).” Business History 63 (6): 988–1006. doi:10.1080/00076791.2019.1598975.

- Roy, W. G. 1983. “The Unfolding of the Interlocking Directorate Structure of the United States.” American Sociological Review 48 (2): 248–257. doi:10.2307/2095109.

- Salvaj, E. 2013. “Cohesión y Homogeneidad. Evolución de la red de directorios de las grandes empresas en Chile, 1969-2005.” In Adaptación. La empresa en Chile después de Friedman, edited by J. Ossandón and E. Tironi, 55–84. Santiago: Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales.

- Salvaj, E., and J. P. Couyoumdjian. 2016. “Interlocked’ Business Groups and the State in Chile (1970–2010).” Business History 58 (1): 129–148. doi:10.1080/00076791.2015.1044517.

- Salvaj, E., and A. Lluch. 2012. “Estudio comparativo del capitalismo argentino y chileno: un análisis desde las redes de directorio a fines del modelo sustitutivo de importaciones.” Redes Revista hispana para el análisis de redes sociales 23 (2): 43–79. doi:10.5565/rev/redes.439.

- Sapinski, J. P., and W. K. Carroll. 2018. “Interlocking Directorates and Corporate Networks.” In Handbook of the International Political Economy of the Corporation, edited by A. Nölke and C. May, 45–60. Cheltenham-Northanmpto, MA: E. Elgar.

- Silva, R., N. Kozitska, C. Oliveira, M. Oliverira, and C. Machado-Santos. 2021. “An Overview of Management Control Theory.” Academy of Strategic Management Journal 20 (2): 1–13.

- Simon, M. C. 1988. “The Rise and Fall of Bank Control in the United States 1890-1939.” The American Economic Review 88 (5): 1077–1093.

- Useem, M. 1984. The Inner Circle: Large Corporations and the Rise of Business Political Activity in the U.S. and the UK. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vasta, M., C. Drago, R. Ricciuti, and A. Rinaldi. 2017. “Reassessing the Bank-Industry Relationship in Italy, 1913-1936: A Counterfactual Analysis.” Cliometrica 11 (2): 183–216. doi:10.1007/s11698-016-0142-9.

- Windolf, P. 2014. “The Corporate Network in Germany, 1896-2010.” In The Power of Corporate Networks. A Comparative and Historical Perspective, edited by T. David and G. Westerhuis, 66–85. New York-London: Routledge.

Appendix