Abstract

This paper analyses embodied experiences of leisure shoppers combining walking and cycling practices in historical city centres. From the perspective of youth, embodied practices and experiences along the Oude Gracht street, an important shopping route in the city centre of Utrecht, are investigated. Based on walk-along interviews with pedestrians and seated interviews with cyclists, the paper reveals leisure shopping as a multimodal exercise with interrelated practices and experiences of walking and cycling. It also unravels shopping routes as arrangements of various sensescapes. They are described by youth ‘in motion’ and en route along the Oude Gracht as (1) calm and beginning, (2) chaos and vehicles, (3) crowding and many choices, (4) crossing and street sellers, (5) chaos and tourists, and (6) cafes and ending. The fluid divisions and connections of these scapes are accompanied by physical and social objects – such as motorized vehicles, a cinema or shop, a large crowd, and street vendors – often generating a switch in the type of walking and cycling. By looking at youth’s practices and experiences, sensescapes appear to be relational in space and time, exposing the complexity of fluid divisions and connections when performing leisure mobilities along shopping routes in city centres.

Introduction

Reflecting entrepreneurial urbanism and neoliberal ideologies (Harvey Citation1989; Peck, Theodore, and Brenner Citation2013), many redevelopment plans for historical city centres across the globe have been implemented with the aim to attract mobile leisure shoppers towards city centres and, in doing so, compete for consumption capital. In addition, another major aim was to promote the mobility of shoppers within the historical urban cores and their distribution throughout the entire network of commercial streets (Carmona Citation2010) – ‘extending the period of “just looking”, the imaginative prelude to buying’ (Crawford Citation1992, 13). To facilitate more extensive routes for leisure shopping and create paths with ‘directional qualities’ (Lynch Citation1960), both the physical features and functional facilities of city centres have been redeveloped, upgraded, differentiated and marketed (Spierings Citation2013; Rabbiosi Citation2015). This further commercialisation of public space was intended to guide consumers to the variety of consumer ‘experiences’ and spending opportunities on offer and, in doing so, boost urban economies (Kärrholm Citation2016; Van den Berg et al. Citation2021).

By walking in streets and on squares, leisure shoppers make several choices to join retail, catering and cultural services as destinations into routes (Kemperman, Borgers, and Timmermans Citation2009), set in an often historical(ised) built environment ‘of play and pleasure, of spectacle and commodification’ (Harvey Citation1991, 60). To get access to the functional facilities and physical features of the city centre for the performance of leisure mobilities, many shoppers will travel by car, bus or train but many others will use the bike (Blondiau, van Zeebroeck, and Haubold Citation2016) – making shopping a multimodal exercise. Cycling also allows shoppers to travel deeper into the city centre, to park closer to preferred destinations (Van der Spek and Scheltema Citation2015), and even to hop on the bike for movement in-between destinations within city centres.

However, as the ‘new mobilities paradigm’ argues, mobility is more than the movement from one destination to another because it is essentially interrelated with representations and embodied practices and experiences (Cresswell Citation2010). This fundamental argument has generated an increasing number and diversity of mobility studies which started looking beyond modal and routes choices, enriching the field of mobility studies. Considering ‘paths as offering not only means of traversing space, but also of ways of feeling, being and knowing’ (Macfarlane Citation2012, 24), mobility studies are now paying serious attention to walking and cycling as embodied practices (e.g. Spinney Citation2006; Degen, DeSilvey, and Rose Citation2008; Middleton Citation2010; Jones Citation2012; Van Duppen and Spierings Citation2013; Simpson Citation2017; Stevenson and Farrell Citation2018; Waitt, Stratford, and Harada Citation2019; Dunlap et al. Citation2021; Ebbensgaard and Edensor Citation2021; Belkouri, Langg, and Laing Citation2022).

Whereas these studies have provided rich insights into embodied practices and experiences of walking and cycling, often taking sensescapes into account, they still lack insights into how various sensescapes are arranged and related along the routes taken by leisure shoppers in city centres. The focus is put on routes here because it is essentially by means of ‘the experience of passing through different territories of the city’ (Sennett Citation2018, 100) that shoppers understand and assemble the city (centre) as an entity. This paper aims to develop a better understanding of how shoppers practice and experience city centre streets by exploring the multiple divisions and connections between sensescapes along routes – also answering to the call to pay attention to how ‘objects of passage’ may generate a switch in the type of walking (Kärrholm et al. Citation2017; Stratford, Waitt, and Harada Citation2021), while adding cycling mobilities. In doing so, the paper looks at how walking and cycling are combined along leisure shopping routes, whereas studies on walking and cycling as embodied practice usually focus on one mobility type or the other.

To analyse how city centres are sensed and scaped by shoppers when performing leisure mobilities on foot and bike – including attention for ‘interactions and potential conflicts between cyclists and pedestrians’ (Middleton Citation2018, 307) –, the Oude Gracht (‘Old Canal’) street in the city centre of Utrecht was selected as case study. With about 350,000 inhabitants, the city of Utrecht is the fourth largest city in The Netherlands. As part of the city centre of Utrecht, the Oude Gracht can be described as an important and popular artery for shopping, due to the amount and variety of consumer services it offers in a historical setting. The street runs on both sides of a canal that was man-made in the 12th century, together with bridges and wharfs. From North to South, it runs through the entire historical urban core and the street is being used by both pedestrians and cyclists.

The paper will analyse the Oude Gracht as shopping route from the perspective of youth living in Utrecht. With about 20 percent of Utrecht inhabitants aged in their twenties (Central Bureau for Statistics Citation2021), young people are an important social group in the city. Moreover, youth are known for often combining walking and cycling when performing leisure mobilities in the city centre (Koelega Citation2014) – making it a highly suitable group for the aim of this paper.

The following section will develop the conceptual framework for analysis, after which the paper continues with explaining the research methods used, together with the strategies applied for participant recruitment. The Oude Gracht street as case study will also be introduced and its local context discussed. The results section unravels embodied practices and experiences of young leisure shoppers and related sensescapes along the Oude Gracht street in Utrecht. The paper concludes with a discussion on divisions and connections between sensescapes as practiced and experienced along shopping routes in city centres.

Leisure shopping and dynamic sensescapes

Traditionally, historical city centres have been a magnetic force for visitors searching for practices and experiences on the nexus between leisure, entertainment and consumption (Gospodini Citation2006). However, it took until the end of the 20th century for this force to be fully embraced and exploited by creating a ‘visitor economy’ (Spierings and van Houtum Citation2008; Hall and Barrett Citation2018) – with consumption spaces considered as ‘trump cards’ in the competition between cities (Crawford Citation1992). This has resulted in increasing urban competition, with many consumption spaces thriving but many others having difficulties to keep their appeal or even struggling to survive (Hughes and Jackson Citation2015).

In an attempt to successfully compete for consumption capital, city centres have been given a make-over and are managed and marketed as the ultimate locations for leisure shopping. This type of shopping ‘mobility as pleasure’ (Jensen Citation2009) can be defined as combining a diversity of retail, catering and cultural services with an often lively social setting and historical urban environment (Jansen-Verbeke Citation1990; Mehta Citation2019). In terms of retail, many studies draw a link between leisure shopping and local speciality stores, open-air markets and exclusive brand stores because the latter types are supposed to stress the distinctiveness and authenticity leisure shoppers are supposed to be looking for (e.g. Zukin et al. Citation2009; Gonzalez and Waley Citation2013; Mermet Citation2017). Not surprisingly, many redevelopment plans for city centre redevelopment aim to capitalize on this link – often feeding into processes of ‘retail gentrification’ (Hubbard Citation2016). According to Borgers and Vosters (Citation2011), however, youth seem to have a higher appreciation for consumption spaces with many of the ubiquitous chain stores and with relatively few retail of the more exclusive kind.

Leisure shopping is undertaken with recreational intentions and, quite similar to tourism, may involve travelling large distances – or even adopting a ‘mobile lifestyle’ as Zukin (Citation1998) would put it – to visit and experience unfamiliar, yet comfortable, places on an occasional basis (Edensor Citation2007). However, it may also involve repeat visits to nearby places and be undertaken there on a frequent basis. On the one hand, such repetition could cultivate routines and ‘situational awareness’ (Te Brömmelstroet Citation2014) – in the sense of shoppers developing an understanding of how other visitors use particular city centre spaces as well as acquiring skills on how to manoeuvre crowds and apply ‘mobile negotiation techniques’ (Jensen Citation2010). On the other hand, it could make leisure shoppers less attentive to the physical and social environment (Degen and Rose Citation2012) – something that is often brought to light when routines get disrupted by sudden physical interventions, such as street maintenance taking place, and implemented social measures, such as during the Covid19-pandemic (see Lucchini et al. Citation2021).

Despite the fact that leisure shopping is usually defined as being performed with recreational motives and, therefore, without the specific purpose of buying goods, such binary thinking does not do justice to the actual complexity of shopping practices and experiences (see also Bäckström Citation2011). When looking at youth, for instance, they seem to combine recreational and purposive motives when shopping (Sane and Chopra Citation2014).

Following Wunderlich (Citation2008), pedestrian shopping could be considered as a mixture of what she defines as ‘purposive’, ‘discursive’ and ‘conceptual’ mobilities. Purposive mobilities involve moving towards a clear destination in the city centre with limited awareness of the physical and social surroundings en route. Discursive (or leisure) mobilities involve having an improvised approach with full awareness of the surroundings. Conceptual mobilities involve having an explorative approach to find new destinations and routes, and expand the ‘mental map’ of the city centre (Lynch Citation1960) – with investigative awareness of the surroundings. Along a shopping route, particular ‘objects of passage’ – such as cars, roads, crowds, individuals, services and landmarks – could via their appraisal ‘trigger’ pedestrian shoppers to switch from one type of pedestrian shopping to another (Kärrholm et al. Citation2017; Stratford, et al. Citation2021).

When shoppers perform leisure mobilities, while potentially combining walking and cycling (Blondiau, van Zeebroeck, and Haubold Citation2016), the experiences they may have in motion are mediated through senses. The visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory and tactile senses of well-equipped bodies facilitate them to see, hear, smell, taste and feel the physical and social environment of city centres (Middleton Citation2010; Jones Citation2012).

Shopping experiences are also mediated through memories, collected through senses in the past, of visits to the exact same but also other city centres (Degen and Rose Citation2012). These experiences of previous visits may have important implications for present embodied practices and experiences in consumption space. This pinpoints what Massey (Citation2005, 14) describes as a ‘throwntogetherness, the unavoidable challenge of negotiating a here-and-now (itself drawing on a history and a geography of thens and theres)’ – implying a relationality of city centres in both space and time, i.e. intertwining the ‘here’ and ‘there’, and the ‘now’ and ‘then’, respectively.

Senses do not stand alone but work and blend together, accounting for embodied experiences as essentially an interplay of the senses (Degen, DeSilvey, and Rose Citation2008). In doing so, ‘they contribute to … an awareness of spatial relationships and an appreciation of the specific qualities of different places’ (Rodaway Citation1994, 37). Together, the multi senses spatialize into so-called urban ‘sensescapes’ – defined as ‘the interactive relationship between sensory body and urban environment’ (Van Duppen and Spierings Citation2013, 235) with different ‘intensities’.

Such a scape should not be understood as a noun suggesting fixed features but as a verb implying continuous dynamics instead (Macfarlane Citation2012). Following this understanding, the above-mentioned interactive relationship ‘develops and changes when we move through the city, resulting in different and dynamic sensescapes along the way’, according to Van Duppen and Spierings (Citation2013, 235). With an emphasis on dynamics, these scapes can be seen as ‘distinctively constituted by a multitude of rhythmic constellations and combinations’ (Edensor and Holloway Citation2008, 484–485).

It is through the body that the ‘polyrhythmia’ is sensed, including ‘psychological rhythms’ of memories (Lefebvre Citation2004). For city centres, the rhythms include, but are not limited to, the rhythms of pedestrians and cyclists, public transport and private cars, leisure and labour, delivery trucks and waste collection, day and night, natural seasons and fashion trends, redevelopment plans and projects, open-air markets and festivals, and bars, restaurants and retail. The latter also tries to ‘organize and synchronise commercial rhythms with important urban rhythms and the mobilities of everyday life’ (Kärrholm Citation2016, 67). This is done with the aim to both attract more leisure shoppers towards the city centre and promote their distribution within its commercial street network as well as to foster the exploration of consumer experiences and spending opportunities en route.

Research methods and case study

To analyse embodied practices and experiences of leisure shopping as well as the multiple divisions and connections between sensescapes along routes in city centres, 50 young participants were interviewed in-depth. The participants were recruited by means of a combination of ‘snowball sampling’ via the social networks of Utrecht University students and via several Utrecht-related group pages on social media platforms. In doing so, a diversity of participants was achieved. They were all aged in-between 18 and 27, with an almost equal gender split and living in a variety of neighbourhoods in the city of Utrecht. Moreover, most participants were still studying – i.e. in a wide range of academic disciplines at a variety of academic research universities, applied sciences universities and colleges for secondary vocational education and training in the Netherlands – whereas some participants were at the beginning of their job career.

As a combination of walking and seated interviews, the research was executed together with the young participants in the years before as well as during the Covid19-pandemic. The project started with doing walk-along interviews with 14 participants in the city centre of Utrecht. During the last decade, the go-along method – as a hybrid of in-depth interviewing and participant observations – has gained in popularity among academics doing research on walking, leisure and public space (Degen and Rose Citation2012; Holton and Riley Citation2014; Moran et al. Citation2020). With ‘the data generated through walking interviews … profoundly informed by the landscapes in which they take place’ (Evans and Jones Citation2011, 849), the method ‘enables deeper investigation into participants’ everyday lives “in place”’ (Finlay and Bowman Citation2017, 266).

In line with the ‘new mobilities paradigm’ (Cresswell Citation2010), walking together with participants also makes that mobility as an embodied practice and experience becomes a core element of the research (Van Melik and Spierings Citation2020). During the walk-along interviews, the participants not only spoke in depth and detail about walking practices and experiences in the city centre landscape but often also about cycling in the city centre of Utrecht when going there with leisure shopping intentions. Therefore, as a second stage in the research project, an additional 16 participants were interviewed on cycling practices and experiences – who, in turn and not surprisingly, also spoke about walking practices and experiences when shopping in the city centre. The latter interviews were conducted in a seated manner because doing bike-along interviews – while riding side-by-side in the rather narrow streets with many strolling shoppers in the historical core of Utrecht – would be an almost impossible and rather dangerous undertaking.

To make the seated interviews more ‘grounded’ in the city centre landscape, participants were asked to draw a mental map of the area under scrutiny (Brennan-Horley Citation2010). More specifically, the mental mapping exercises were used to make the seated interviews ‘more informed by the landscapes’ (Evans and Jones Citation2011) in which the cycling practices and experience take place.

After the Covid19-pandemic hit, various regulations including lockdowns were implemented, eased and lifted over time for city centres in the Netherlands. To take account of the effects of these pandemic-induced measures on practices and embodied practices of leisure shopping, it was decided to add a third stage to the research project – with emphasis on analysing youth’s sense of crowding. This was done when the shops were open again – but with regulations still implemented to control for visitor density and inter-personal distance, including the enlargement of the pedestrian zone in the city centre of Utrecht. Because the non-cycling policy during retail business hours was also rather heavily enforced in the city centre, the focus was put on walking mobilities and walk-along interviews with an additional 20 young participants were arranged.

The walk-along interviews at the start of the project revealed diverse shopping routes used by youth in the city centre of Utrecht. However, it also clearly pinpointed the Oude Gracht (‘Old Canal’) street as an essential constituent of their city centre visits. For that reason, this about 1.8 kilometres long shopping street running through the entire historical core of Utrecht () was selected as case study for the paper.

The Oude Gracht street runs on both sides of a canal that was created in the 12th century with several spanning bridges (IJsselstijn Citation2022). At street level, a large number and variety of shops, bars, restaurants and other consumer services is now being offered, set in an historical built environment (see and later pictures in the results section for additional details; all pictures made by the author). Below street level, many warehouses and wharfs were constructed along the canal – now often used by bars and restaurants with terraces on the water side (). With the pandemic-related lockdowns and regulations no longer in place, the shopping street is being used by both pedestrians and cyclists, while most of the street is designated as pedestrian zone during retail business hours.

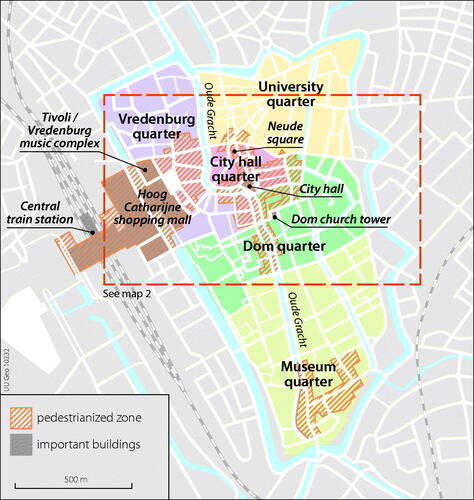

Figure 1. Oude Gracht running through Utrecht city centre (with frame). Credits: Utrecht University Geo Communications & Marketing.

To attract leisure shoppers towards the city centre and promote their distribution within its street network with a variety of consumer experiences on offer, the historical urban core of Utrecht – i.e. the area enclosed by a canal in – is being marketed by distinguishing 5 so-called ‘city centre quarters’. These are: 1) the ‘Vredenburg quarter’ with the main concentration of retailers, including the Hoog Catharijne shopping mall, and the Tivolo / Vredenburg music complex, 2) the ‘University quarter’ with local events and specialized retailers, bars and restaurants, 3) the ‘City hall quarter’ with many family-run businesses and specialized retailers, bars and restaurants, 4) the ‘Dom quarter’ with several historical monuments, including the iconic Dom church tower, and small alleys with authentic shops and specialized restaurants, and 5) the ‘Museum quarter’ with several museums, a large variety of retailers and small bars in a green environment (Centrum Management Utrecht Citation2022). The Oude Gracht runs through all of the 5 city centre quarters and the in-depth interviews therefore touched upon several parts and aspects of each.

All in-depth interviews were recorded with consent and field notes were taken with respect to personal characteristics of the participants, the setting selected by each participant for the seated interviews, the site selected by each participant for the start of the walk-along interviews, and the weather conditions of the walk-alongs themselves. The interviews were fully transcribed and the transcripts were coded with the help of Maxqda software for the identification and categorization of themes. The coding process generated an arrangement of 6 important themes for interrelated sensescapes along the Oude Gracht. These themes and their scapes in the city centre of Utrecht will be elaborated on in the results section, with selected quotes translated from Dutch into English by the author. Moreover, for anonymity purposes, the names of participants have been replaced with fictional ones.

Shopping and sensescapes along the Oude Gracht

shows a large part of the Oude Gracht running through the city centre of Utrecht – with a spatial indication of the arrangement of urban sensescapes, involving rather fluid and gradual transitions than clear-cut and sudden borders, as practiced and experienced by the research participants. These sensescapes are ‘calm and beginning’, ‘chaos and vehicles’, ‘crowding and many choices’, ‘crossing and street sellers’, ‘chaos and tourists’, and ‘cafes and ending’. Together they comprise about a kilometre of the Oude Gracht street with a total length of 1.8 kilometres.

In the following, each of the urban sensescapes will be discussed in itself and in relation with others, while moving from North to South. Needless to say that the Oude Gracht street may also be used by youth in a different direction and in a more selective manner. Moreover, they may also use the street in a more elaborate manner but the sensescapes as indicated in show the main part of the Oude Gracht used by the research participants when visiting the city centre with shopping motives. With respect to the impact of the Covid19-pandemic on youth’s sense of crowding, mainly the sensescapes ‘crowding and many choices’ and ‘chaos and tourists’ were reflected on by participants.

Calm and beginning

From the perspective of youth, the ‘first’ sensescape along the Oude Gracht can be typified as rather quiet with ‘calm’ rhythms. It stands in contrast to the nearby shopping street called Voorstraat which Maarten described as ‘a very lively, busy street with a lot of traffic, cars, and also a lot of different shops’. However, not many shops and mostly houses can be found in the Oude Gracht area under scrutiny (). According to Luc who also lives there, this is what makes the area quiet and calm. More specifically, in the upper segment of the sensescape: ‘it is a lot calmer and there are hardly any shops really, the city centre has not begun there yet. Of course, the Oude Gracht is in the city centre but it is not part of the walking route of the standard shopper really, as opposed to here [the area with chain stores and crowding he was in when reflecting on the “first” sensescape]’ (Luc).

This quote can be further clarified by disentangling two often confused concepts. These are ‘inner city’ – i.e. the historical core of the city, potentially still demarcated by remaining sections of city walls and canals () – and ‘city centre’ – i.e. the network of commercial streets and squares that has developed from within the inner city, possibly also beyond its historically-defined demarcations (Spierings Citation2006). As such, the upper segment of the sensescape is considered part of the historical inner city but not yet part of the commercial network of city centre streets – also excluding the upper segments of the marketed ‘Vredenburg’ and ‘University’ quarters from being part of the city centre according to youth.

According to participants, it is near the Pathé Rembrandt cinema that the ‘threshold’ of the Oude Gracht becoming a shopping street can be witnessed and where, therefore, the city centre is ‘beginning’. The cinema is located near the busy road crossing the Oude Gracht street and it is in-between the cinema and this road that a couple of chain stores can be found. The bike shed in front of the cinema is used to park the bike when going to the movies but also when going shopping in the city centre with leisure motives. As Bas put it: ‘If I am really going to look for something and I do not know exactly what, then I park it [the bike] … at the Pathé Rembrandt cinema’.

The cinema could therefore be seen as an ‘object of passage’ near which participants switch from being ‘purposive’ cyclists to ‘discursive’ pedestrians. However, overall, the young participants are cycling towards a pre-determined destination for shopping with more ‘purposive’ intentions and park their bike close by.

Chaos and vehicles

The next sensescape is dominated by a busy two-lane road with different rhythms of pedestrians, cyclists and motorized vehicles () – although much less so during the lockdowns of course. The road runs through the city centre of Utrecht and crosses the Oude Gracht. According to Nick, it is ‘the area in Utrecht with the highest concentration of cyclists’ and Jorn added that the area differs a lot from the Vismarkt street, where pedestrians and cyclists also share space, – as will be discussed in the upcoming ‘chaos and tourists’ sensescape – due to the motorized vehicles. More specifically, he does not feel like walking in the area under scrutiny because of ‘all those buses driving by with the noise involved’.

It is an important bus station located adjacent to the bridge that brings many buses to the city centre, making the area quite noisy and rather hectic. According to Ellen, you have to be really careful when walking across the busy road. According to her, doing so requires ‘full attention for the traffic which is not nice. You really have to look sideways 5 times before you can pass’ – with cars adding further complexity and chaos by sometimes ‘forcing pedestrians onto the cycling path’ (Benjamin). In line with the argument by Waitt et al. that ‘the signs, rhythms, sounds, and movements of vehicles and the dominating and territorializing mien of drivers’ transform a city centre into ‘inhospitable territory for pedestrians’ (Citation2019, 935), Benjamin concludes that pedestrians are ‘guests’ in the sensecape although for it to be part of a shopping street, pedestrians should be prioritized instead.

Interestingly, from the perspective of cyclists, pedestrians add more to the chaos than buses. Pedestrians are seen as rather ‘unpredictable’ and therefore requiring alertness – e.g. because they may ‘run and suddenly cross the road because they want to catch the bus’ (Jasmijn) – whereas buses are seen as ‘predictable’ (Tessa) because they will stay in their demarcated lane. For Levi, the traffic situation in the area brings a less comfortable feeling because ‘everyone walks, bikes and drives fast. You feel rushed, you are occupied with going to a destination, you are traversing’. Both motorized vehicles and pedestrians could therefore be seen as ‘objects of passage’ turning participants into alert, careful and ‘purposive’ pedestrians and cyclists.

When it comes to the consumer services on offer, youth do not seem to make much use of them – with the Intersport chain store, part of the University quarter, as important exception. However, the Intersport store building is often described by participants as ‘ugly’ and the same can be said for several other buildings located nearby – because they do not have an ‘authentic style’ (Florian) and therefore do ‘not go well with [the city centre of] Utrecht’, according Charissa. Luc added the Neude building to the list of ‘ugly’ buildings. Despite not being directly located in the sensecape, the building is still influential because it is clearly visible from the bridge in the background due to its height (). These buildings are contrasted with the historical and ‘beautiful’ Oude Gracht in the area – which, according to Cathelijne, ‘is the first section of the canal you encounter when you enter Utrecht, for instance, by bus’.

Crowding and many choices

Then participants set foot in a sensescape which is part of both the Vredenburg quarter and the City hall quarter. It is in this scape that youth spend most of their time when shopping along the Oude Gracht street. In line with Hahm, Yoon, and Choi (Citation2019), the main reason for staying in the area for a relatively long time is that there they ‘could have many choices of shopping’ (2019, 9). The area is dominated by (inter)national stores at eye level but residences reveal themselves, when looking up, with ‘very beautiful and sympathetic … facades above the shops’ (Ernst). The chain stores focus on clothing, according to participants, and these stores are considered to target them with ‘lots of choice, something for everyone’, as Nick put it. Saskia added the importance of the price level of the shops by arguing that ‘they have a lot and things are inexpensive’.

Next to talking about many choices when it comes to clothing shops, many participants also spoke about the ‘abundant supply of food, drinks, and cafes and restaurants’ (Luc) in the area. In this context, Jasper pinpointed the appealing mix of consumer services in the area, while making a comparison with the nearby Hoog Catharijne shopping mall mainly focusing on shops. Participants, for instance, spoke about having an Italian ‘Mario sandwich’ or Belgian chips along the Oude Gracht. According to Jorn, the chips chop and the nearby McDonald’s together generate a strong chips scent, pointing at a specific subarea where ‘snacking dominates a bit’.

When it comes to the restaurants in the area, however, they are ‘great for the atmosphere but for youth mostly too expensive for eating there’ (Bas). Most participants therefore use the restaurants as well as the cafes and their terraces at the Neude square, located nearby the Oude Gracht. Some markets stalls on the spanning bridges – locating at these ‘crowded locations’ (Luc) to adjust to the flows of shoppers (Kärrholm Citation2016) – also sell affordable food and drinks while several others sell flowers. The latter were experienced quite different by participants, with Ernst arguing that the shouting of market adds ‘authenticity’ to the area whereas Ellen is not so much in favour of the vendors because ‘they are always shouting after you and … sometimes are pushy’.

Due to the large number of, also non-youth, visitors in the area, participants most of the time experience a sense of ‘cozy crowding’, bringing appealing liveliness to the Oude Gracht street. During peak hours, however, crowding can be assessed more negatively and market stalls along the Oude Gracht may add to this because they, together with waiting customers ‘in case of a popular stall’ (Thijs), take up space on the spanning bridges (). Negative crowding may be experienced when things are ‘a bit too busy’, according to Saskia. She continued that in that case you are ‘fully focused on getting out of the way of others instead of pleasantly browsing around’ (Saskia). In addition, Benjamin argued that ‘when it is very busy, I am rather inclined to move to my goal faster’ instead of going for a ‘leisurely stroll through the city [centre]’ although, according to Simon, ‘you often have to walk behind someone for a long time because you simply cannot overtake’ and therefore you have to adjust to the rhythm of others. A large crowd could therefore be seen as an ‘object of passage’ making relaxed and ‘discursive’ strollers change into faster and more ‘purposive’ walkers.

For youth cycling through the city centre, crowding makes it difficult to find a place to park the bike along the Oude Gracht, according to Violet, in particular because they aim to park ‘as close as possible’ (Jasper) to the shopping destination. According to Roos, however, parked bikes on the spanning bridges adds to the sense of crowding because they are ‘standing in the way very much’. To cope with negative crowding, some participants may apply both ‘temporal and spatial strategies’ of avoidance (Popp Citation2012). This involves shopping along the Oude Gracht during off-peak hours – to avoid ‘people doing daytrips to Utrecht and before Corona also tourists’ (Lucia) – and shopping online to avoid the Oude Gracht during peak hours, with online shopping having seen a surge during to the pandemic (Ter Haar and Quix Citation2021).

During the Covid19-pandemic, it was much less crowded in the city centre, in particular when ‘non-essential’ shops, cafes and restaurants were closed. According to two participants living in the city centre, mediated by pre-pandemic memories of crowding, it made the area ‘really quiet’ (Sophie) and ‘completely deserted, almost like a ghost town’ (Lucia). The disappeared crowd as ‘object of passage’ disrupted shopping routines and made participants change into ‘conceptual’ walkers with a slower rhythm and more awareness for the environment. According to Lucia, ‘then you can see completely different things, you did not see before’.

When the stores re-opened with restrictions for the maximum number of visitors, the large crowds did not return to the Oude Gracht yet. However, participants still experienced negative crowding ‘when having to wait somewhere while standing in line, which has worsened with Corona. For instance, due to the one-way traffic [implemented during the pandemic] in the city centre’ (Piet) but also due to the lines themselves with people waiting outside shops. In this context, Michael spoke about the lines as ‘obstacles’ because they take up space in the shopping street along the Oude Gracht. In addition, despite the smaller number of shoppers, overtaking can still be a complex undertaking when trying to keep 1.5 meters distance from others. As Inge explained: ‘Sometimes, when I am walking and I want to overtake someone, then I have to go out of my way to avoid the person, but then someone else approaches, making it [overtaking] impossible again’.

Crossing and street sellers

From a sensescape characterized by dwelling, youth enter a square that is demarcated by a few shops and the city hall – i.e. the building with pillars in and part of the City hall quarter. Youth mainly use the square for crossing from one city centre area to another. As Lidwien put it: ‘Nothing is being done with it [the square in front of the city hall]. Now it is more a passageway than a place to stop’. In the words of Von Schönfeld and Bertolini (Citation2017), the urban square emphasizes ‘mobile functions’, with shoppers moving through, over ‘stationary functions’.

To explain the lack of stationary functions and related activities of dwelling on the square, Lidwien points at the city hall façade as ‘quite closed’ although its pillars seem to indicate the ‘grand entrance’ of the building. However, festivities such as wedding ceremonies take place on the other side of the city hall. The closed nature and hidden function of the city hall building also clearly speak from the argument raised by Violet when saying ‘I can see a large building over there but I do not know what it is for really’.

The area being used as a passageway makes it busy with people crossing but, according to participants, in case of good summer weather the stairs of the city hall building are used to hang out and relax in the sun. In addition, street musicians are sometimes playing guitar and singing, according to Jorn, which brings liveliness to the square. However, not all street musicians are being appreciated equally, street organists not so much in particular. Peter even argued that he gets annoyed, especially with ‘those large organs in combination with the rattling sound of shaking “begging bowls”’. According to him, these organs are ‘standing in the way’ when it is busy in the city centre and the music they make is ‘just not chill’.

In addition to street musicians, street sellers, interviewers and campaigners often concentrate on the square – although not during the lockdowns. They are, for instance, selling newspaper subscriptions, asking for donations to charities, recruiting research participants, handing out political flyers and requesting to sign petitions – e.g. against organ harvesting in China, as in . Some participants reveal a quite neutral stance towards street sellers, interviewers and campaigners because, as Violet puts it: ‘usually I just say “no thank you” and continue my stroll, and then they are content’. However, most participants talked about rather ‘pushy’ street sellers who are trying to persuade them into getting a subscription.

As a response, an often applied strategy is to accelerate when approaching street sellers. More specifically, as Ton put it: ‘I walk fast and look down because then nobody will ask you anything’. As such, street sellers, interviewers and campaigners could be considered as ‘objects of passage’ making youth switch from being already ‘purposive’ and rather fast walkers when crossing the square to even faster walkers, looking down to avoid persuasive eyes and pushy speech.

Chaos and tourists

The next sensescape is dominated by a rather chaotic traffic situation with ‘rather slow’ (Quinten) pedestrians and faster cyclists sharing limited space in a street section called Vismarkt (). With traffic coming from both directions, the street section was typified by Piet as ‘a real bottleneck in the city [centre]’ where pedestrians ‘always have to be aware’. From a cyclists’ perspective, Luc describes the situation as follows: ‘When it’s busy then it is a “hell” … especially on Saturday afternoon it’s impossible … then lots of people are walking there so you cannot pass through by bike, although it is allowed to cycle there’.

However, as the quote also shows, not everybody knows that cycling is not allowed during retail business hours on Saturday and Sunday. Moreover, pedestrians are not always aware that cycling is officially allowed in the area outside those hours. The resulting confusion may generate discussions between pedestrians and cyclists, according to Ton. Interestingly, not all participants are aware of being allowed to cycle in the area either. Even those participants do so, simply because ‘it is the quickest by bike’, as Saskia put it, and despite the bumpy road making your ‘bike almost fall apart’ (Eva).

Some participants typified the chaotic situation as sometimes ‘annoying’ – when cyclists are ringing their bells rather aggressively, for instance, – but also quite ‘dangerous’ when many pedestrians are around – often resulting in cyclists stopping and ‘continuing on foot with the bike in the hand … or [following] a cyclist in front … who clears the road’ (Karlijn). Several also take care by slowing down to adjust to the rhythm of pedestrians and manoeuvre through with only ‘little accidents’ (Jasper) occurring now and then – indicating an ‘organized chaos’ (Pelzer Citation2012) in the area.

Others argued that the situation does not bother them so much. Benjamin, for instance, argued that ‘you get used to expecting cyclists here, meaning that, when walking here, I do not step aside anymore but expect the cyclist to adapt’. As such, participants seem to have developed ‘situational awareness’ (Te Brömmelstroet Citation2014) for which they can profit from the combined perspectives of being pedestrian and cyclist. In this context, Luc finds himself ‘a bit of a hypocrite’ if he would describe cyclists as bothersome when walking in the area – because he himself also cycles there sometimes.

Tourists are attracted to the area – located in the Dom church quarter – for visiting and photographing the Dom church tower in combination with other historical buildings (see for a view on the area with a scaffolded church tower). As Nick put it: ‘I have a lot of foreign friends and they know very little about Utrecht really, but this is the image they know. This is “classic”, you have the canal here with the buildings in the old style and then you have the Dom [church tower] in the background which obviously is very iconic for Utrecht’.

When it comes to the shops on offer in the area, they are not often used by youth. This seems to resonate with Peter arguing that he ‘does not know really well what can be found there’. In addition, Karlijn rather loosely talks about a ‘mix of hipster [stores]’ but also quite specifically about a coffeeshop in the area. Interestingly, for some cyclists, the smell of weed was described as a ‘landmark’ along their cycling route through the city centre while for others the coffee shop was seen as bringing tourists to the area.

When cycling through the area, special attention is required for tourists according to participants. They are adding further complexity to the chaos because, according to Maarten, ‘there are many tourist who are not paying any attention [to cyclists] at all and are fully focused on making photographs of everything, creating extra danger’. ‘When seeing the Dom church tower, they stop’ (Thijs) to make a picture ‘in the middle of the cycling path’ (Eva), also because they think that cycling is not allowed there and therefore ‘do not expect cyclists’ (Lieke). In addition, Lidwien argued: ‘When cycling there, I often think “you non-Utrecht people”, you do not know at all how things work around here, get off my cycling path’.

This quote points at a lack of ‘situational awareness’ (Te Brömmelstroet Citation2014) of ‘outsiders’, tourists in particular, which seems to make them rather ‘unpredictable’, requiring alertness – similar to but often more so than for the ‘unpredictable’ pedestrians in the ‘chaos and vehicles’ sensescape. This may aggravate the chaotic traffic situation in the area as well as, in line with Neuts and Vanneste (Citation2018), the perception of crowding involved, due to the ‘deviating’ behaviour of tourists.

During the COVID 19-pandemic, there were hardly any tourists visiting the area and cycling was officially banned in order to create more space for pedestrians aiming to keep 1.5 meters distance. This was noticed by participants memorizing the pre-pandemic situation in the area. However, according to Roos, ‘now people are more nervous … when you walk or cycle there, they are “unpredictable”’ with respects to their movements – still creating a sense of crowding. Altogether, pedestrians in general but tourists suddenly stopping to make a picture in particular could be seen as ‘objects of passage’ turning participants into alert, careful and actively warning cyclists.

Cafes and ending

Participants described the ‘final’ sensescape as an area with several cafes where you can sit on terraces. Not many seem to use the facilities there though and Bas even describes the businesses as catering to customer who are ‘a bit older’. This contrasts with the Neude square – located near the ‘crowding and many choices’ sensescape and in the ‘City hall quarter’ – with many cafes and terraces that are highly popular among youth. In terms of retail, a couple of respondents described childhood memories of a skate shop that used to be located in the area. Jorn, for instance, remembered visiting the place together with his father to buy his first skateboard, by enthusiastically adding: ‘and then you were allowed to practice on the street [on a quiet day] and the man from the store started showing me all kind of tricks’.

Further to the south is where, according to participants, a ‘threshold’ can be witnessed of the Oude Gracht becoming a mostly residential street and where, therefore, the city centre is ‘ending’ – i.e. near the Dille & Kamille chain store. According to Ton, the reason for this is that ‘in-between the Twijnstraat [a shopping street running parallel to the most southern part of the Oude Gracht] and Dille & Kamille not much can be found. Now and then a small shop, but no continued shopping street’. Bas does not even know where the Twijnstraat can be found because ‘he never ever goes there’. Interestingly, this implies that a large part of the Oude Gracht and, at the same time, the entire marketed ‘Museum quarter’ is not considered to be part of the city centre according to youth.

To pinpoint the ending of the city centre, Lidwien talks about a ‘border’. This speaks to the conventional perception of a border as separating ‘barrier’ demarcating an ending whereas a border could also be understood as connecting ‘bridge’ indicating a beginning (Newman Citation2006). Resonating with the latter understanding, Levi argued that according to his perception ‘all shops are up from here [the Dille & Kamille store] so when I am looking for something then I start here’. Like other participants, he then parks his bike close to the Dille & Kamille chain store () – making it into an ‘object of passage’ near which a switch from ‘purposive’ cyclists to ‘discursive’ pedestrians occurs.

Regardless of whether the city centre is considered ending or beginning near the Dille & Kamille chain store, participants usually turn around by continuing their stroll or start their stroll via the spanning bridge into the so-called Lijnmarkt (). This shopping street runs parallel to the Oude Gracht and leads towards the areas with street sellers, chain stores and crowding. The street is described as rather posh with specialty stores but Peter added that it is also ‘more boring and more timid than the other streets, than the Vismarkt and the Oude Gracht’. The more calm rhythms sets the street apart from the much more chaotic traffic situation in the Oude Gracht area under scrutiny that is also considered by youth to be rather similar to the traffic situation in the Vismarkt.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper has analysed how youth experience an important shopping route in the city centre of Utrecht. While combining walking and cycling practices, youth apply a variety of techniques of negotiating space and manoeuvring through the crowd, while adjusting their rhythm to other pedestrians and cyclists. In doing so, chaotic traffic situations are often managed through slowing down and carefulness based on ‘situational awareness’ (Te Brömmelstoet 2014) whereas encounters with street sellers are usually avoided through acceleration.

Overall, in line with Sane and Chopra (2104), youth combine purposive and leisure motives as well as mobilities when shopping along the Oude Gracht. In terms of mobilities, walking and cycling have also shown to be complementary practices for leisure shopping, with the bike not only used for travelling towards the city centre but also within it. Combining both types of mobility in one study, as opposed to previous studies on embodied walking and cycling practices usually focussing on one or the other (e.g. Degen, DeSilvey, and Rose Citation2008; Dunlap et al. Citation2021; Belkouri, Lanng, and Laing Citation2022), has provided the following important insights.

First, various ‘objects of passage’ have been indicated to induce modal shifts when leisure shopping in city centres. For instance, particular consumer services and when many pedestrians are around may make youth switch from being cyclists to pedestrians. Secondly, walking and cycling have been pinpointed as relational practices and experiences, influencing one another during leisure mobilities. For instance, pedestrians may be less annoyed with cyclists due to ‘psychological rhythms’ of memories (Lefebvre Citation2004) regarding their own use of the city centre as a cyclist.

Whereas several existing studies on embodied practices and experiences of walking and cycling already provided insights into urban sensescapes (e.g. Spinney Citation2006; Middleton Citation2010; Jones Citation2012; Van Duppen and Spierings Citation2013; Simpson Citation2017; Stevenson and Farrell Citation2018; Waitt, Stratford, and Harada Citation2019; Ebbensgaard and Edensor Citation2021), they lacked attention for the arrangement of sensescapes along leisure shopping routes. In-depth interviews with youth on walking and cycling along the Oude Gracht revealed the following arrangement of sensescapes: (1) ‘calm and beginning’ where mostly houses and not many shops can be found in a rather quiet setting, and where the Oude Gracht becomes a shopping street, (2) ‘chaos and vehicles’, dominated by a busy road with pedestrians, cyclists and motorized vehicles, and where alertness is required when traversing a rather inhospitable setting, (3) ‘crowding and many choices’ with mostly chain stores and where youth like to dwell but also with processes of negative crowding, potentially resulting in avoidance during peak hours, (4) ‘crossing and street sellers’, mainly used as a passageway and where rather pushy street sellers tend to concentrate together with street musicians, interviewers and campaigners, often resulting in youth accelerating, (5) ‘chaos and tourists’ with pedestrians and cyclists sharing limited space, requiring alertness when manoeuvring through the crowd with special attention for rather ‘unpredictable’ tourists, and (6) ‘cafes and ending’ where several cafes with terraces can be found, and where the Oude Gracht becomes a mostly residential street again.

By exposing both the variety and complex relatedness of sensescapes en route in city centres from the perspective of youth, this paper has provided two important contributions to previous studies on urban sensescapes.

First, various physical and social objects – such as motorized vehicles, a large crowd, and street vendors – have been indicated to accompany fluid divisions and connections of sensescapes. Moreover, these physical and social ‘objects of passage’ (Kärrholm et al. Citation2017; Stratford, Waitt, and Harada Citation2021) often induce a switch in the type of walking and cycling. Chaotic traffic situations with physical objects such as cars and buses often make youth temporarily less ‘discursive’ and more ‘purposive’, as Wunderlich (Citation2008) would put it. Rather unpredictable ‘social objects’ such as tourists seem to generate a switch from being relaxed yet mindful cyclists to much more careful ones with high pedestrian awareness – also extending the ‘objects of passage’ discussion beyond the focus on walking. Interestingly, during lockdowns, disappeared crowds as ‘objects of passage’ seem to have disrupted shopping routines by adding more emphasis on ‘conceptual’ walking along the Oude Gracht.

Secondly, sensescapes have been pinpointed as relational in space and time, not only with each other along the shopping route but also with other streets and squares across the city centre. For youth, for instance, a dividing threshold between a calm and mostly residential area and the crowded shopping area along, but also beyond, the Oude Gracht indicates where the city centre ‘begins’. The city centre seems to ‘end’ for them where the Oude Gracht becomes mostly residential again. The city centre ‘ending’ is distant, in an absolute sense, from other city centre areas in which youth spend most of their time when leisure shopping. However, the ‘here and there’ (Massey Citation2005) become closely connected and their experiences related when youth compare the type of shops and cafes in those areas – also indicating, and resonating with Borgers and Vosters (Citation2011), that youth prefer ubiquitous chain stores over the more exclusive kind when leisure shopping.

In addition, the crowded sensescapes in which youth feel targeted by chain stores has highlighted how, during the Covid19-pandemic and in line with Degen and Rose (Citation2012), memories mediate experiences of crowding – by intertwining the ‘then and now’ (Massey Citation2005). Interestingly, less visitors in the city centre due to social regulations not necessarily resulted in the experience of less, but rather different, crowding – mainly due to the aim of keeping 1,5 meters inter-personal distance when shopping.

The complexity of fluid divisions and connections between sensescapes along a shopping route, and beyond, raises important questions for the conventional approach of city centres to promote the distribution of leisure shoppers within their street network. This is often done by distinguishing and marketing subareas – or ‘city centre quarters’ in the case of Utrecht (Centrum Management Utrecht Citation2022) – with a particular functional profile and identity, and with supporting investments to physically upgrade the street layout, pavement and furniture.

Notwithstanding the effects this may have on the knowledge base and ‘mental map’ (Lynch Citation1960) of leisure shoppers regarding destinations in the city centre worth visiting, it is ultimately streets and squares combined into walking and cycling routes by shoppers that may bring them to the marketed subareas. Developing a detailed understanding of the embodied practices and experiences of leisure mobilities, shopping routes and sensescapes is therefore essential for grasping how shoppers ‘in motion’ understand the composition of city centres and why they choose, but also tend to overlook and perhaps deliberately avoid, particular subareas and destinations. This may involve explorative – or ‘conceptual’ as Wunderlich (Citation2008) would put it – walking and cycling to potentially merge unfamiliar city centre streets and squares into new shopping routes.

To further develop the understanding of shopping routes as dynamic arrangements of sensescapes, taking the perspectives of a diversity of leisure shoppers – with difference in age, gender, ethnicity, education, income level and bodily capacities – would be an important step forward.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on fieldwork done by Jasmijn Koelega, Werner Pison and Borre van der Mark for their Master thesis in Urban Geography (see also Koelega Citation2014, Pison Citation2017, and Van der Mark Citation2020). These Master theses were part of the larger Shopping trajectories and (un)familiarity in the city centre of Utrecht project. Much gratitude goes to the students for their assistance in the fieldwork and all respondents for their participation in the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bäckström, Kristina. 2011. “Shopping as Leisure: An Exploration of Manifoldness and Dynamics in Consumers Shopping Experiences.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 18 (3): 200–209. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2010.09.009.

- Belkouri, Daria, Ditte Bendix Lanng, and Richard Laing. 2022. “Being There: Capturing and Conveying Noisy Slices of Walking in the City.” Mobilities 17 (6): 914–931. doi:10.1080/17450101.2022.2045871.

- Blondiau, Thomas, Bruno van Zeebroeck, and Holger Haubold. 2016. “Economic Benefits of Increased Cycling.” Transportation Research Procedia 14: 2306–2313. doi:10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.247.

- Borgers, Aloys, and Cindy Vosters. 2011. “Assessing Preferences for Mega Shopping Centres: A Conjoint Measurement Approach.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 18 (4): 322–332. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2011.02.006.

- Brennan-Horley, Chris. 2010. “Mental Mapping the ‘Creative City.’” Journal of Maps 6 (1): 250–259. doi:10.4113/jom.2010.1082.

- Carmona, Matthew. 2010. “Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (1): 123–148. doi:10.1080/13574800903435651.

- Central Bureau for Statistics. 2021. “Inwoners per Gemeente.” https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/regionaal/inwoners.

- Centrum Management Utrecht. 2022. “Centrumkwartieren.” https://cmutrecht.nl/centrumkwartieren/.

- Crawford, Margaret. 1992. “The World in a Shopping Mall.” In Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, edited by Michael Sorkin, 3–30. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Cresswell, Tim. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1068/d11407.

- Degen, Monica, Caitlin DeSilvey, and Gillian Rose. 2008. “Experiencing Visualities in Designed Urban Environments: Learning from Milton Keynes.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (8): 1901–1920. doi:10.1068/a39208.

- Degen, Monica Montserrat, and Gillian Rose. 2012. “The Sensory Experiencing of Urban Design: The Role of Walking and Perceptual Memory.” Urban Studies 49 (15): 3271–3287. doi:10.1177/0042098012440463.

- Dunlap, Rudy, Jeff Rose, Sarah H. Standridge, and Courtney L. Pruitt. 2021. “Experiences of Urban Cycling: Emotional Geographies of People and Place.” Leisure Studies 40 (1): 82–95. doi:10.1080/02614367.2020.1720787.

- Ebbensgaard, Casper Laing, and Tim Edensor. 2021. “Walking with Light and the Discontinuous Experience of Urban Change.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 46 (2): 378–391. doi:10.1111/tran.12424.

- Edensor, Tim. 2007. “Mundane Mobilities, Performances and Spaces of Tourism.” Social & Cultural Geography 8 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1080/14649360701360089.

- Edensor, Tim, and Julian Holloway. 2008. “Rhythmanalysing the Coach Tour: The Ring of Kerry, Ireland.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33 (4): 483–501. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2008.00318.x.

- Evans, James, and Phil Jones. 2011. “The Walking Interview: Methodology, Mobility and Place.” Applied Geography 31 (2): 849–858. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005.

- Finlay, Jessica M., and Jay A. Bowman. 2017. “Geographies on the Move: A Practical and Theoretical Approach to the Mobile Interview.” The Professional Geographer 69 (2): 263–274. doi:10.1080/00330124.2016.1229623.

- Gonzalez, Sarah, and Paul Waley. 2013. “Traditional Retail Markets: The New Gentrification Frontier?” Antipode 45 (4): 965–983. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01040.x.

- Gospodini, Aspa 2006. “Portraying, Classifying and Understanding the Emerging Landscapes in the Post-Industrial City.” Cities 23 (5): 311–330. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2006.06.002.

- Hahm, Yeankyoung, Heeyeun Yoon, and Yunwon Choi. 2019. “The Effect of Built Environments on the Walking and Shopping Behaviors of Pedestrians; A Study with GPS Experiment in Sinchon Retail District in Seoul, South Korea.” Cities 89: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.020.

- Hall, Tim, and Heather Barrett. 2018. Urban Geography. London: Routledge.

- Harvey, David 1989. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler 71 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583.

- Harvey, David 1991. “The Urban Face of Capitalism.” In Our Changing Cities, edited by John Fraser Hart, 50–66. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Holton, Mark, and Mark Riley. 2014. “Talking on the Move: Place-Based Interviewing With Undergraduate Students.” Area 46 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1111/area.12070.

- Hubbard, Phil 2016. The Battle for the High Street: Retail Gentrification, Class and Disgust. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hughes, Cathy, and Cath Jackson. 2015. “Death of the High Street: Identification, Prevention, Reinvention.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 237–256. doi:10.1080/21681376.2015.1016098.

- IJsselstijn, Marcel. 2022. “De Oudegracht in Utrecht: Enkele Nieuwe Inzichten en Hypothesen over de Ruimtelijke Ontwikkeling van de Middeleeuwse Stadshaven.” In Het Landschap Beschreven: Historisch-Geografische Opstellen voor Hans Renes, edited by Jaap Evert Abrahamse, Henk Baas, Sonja Barends, Drée van Marrewijk, Ben de Pater, and Michiel Purmer, 195–204. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren.

- Jansen-Verbeke, Myrian. 1990. “Leisure + Shopping = Tourism Product Mix.” In Marketing Tourism Places, edited by Gregory Ashworth, and Brian Goodall, 128–137. London: Routledge.

- Jensen, Ole B. 2009. “Flows of Meaning, Cultures of Movements – Urban Mobility as Meaningful Everyday Life Practice.” Mobilities 4 (1): 139–158. doi:10.1080/17450100802658002.

- Jensen, Ole B. 2010. “Negotiation in Motion: Unpacking a Geography of Mobility.” Space and Culture 13 (4): 389–402. doi:10.1177/1206331210374149.

- Jones, Phil. 2012. “Sensory Indiscipline and Affect: A Study of Commuter Cycling.” Social & Cultural Geography 13 (6): 645–658. doi:10.1080/14649365.2012.713505.

- Kärrholm, Mattias. 2016. Retailising Space: Architecture, Retail and the Territorialisation of Public Space. London: Routledge.

- Kärrholm, Mattias, Maria Johansson, David Lindelöw, and Inês A. Ferreira. 2017. “Interseriality and Different Sorts of Walking: Suggestions for a Relational Approach to Urban Walking.” Mobilities 12 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1080/17450101.2014.969596.

- Kemperman, Astrid D.A.M., Aloys. W. J. Borgers, and Harry J. P. Timmermans. 2009. “Tourist Shopping Behavior in a Historic Downtown Area.” Tourism Management 30 (2): 208–218. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.06.002.

- Koelega, Jasmijn. 2014. “Op Pad in de Stad: De Utrechtse Binnenstad in de Beleving van Jongeren.” Urban Geography Master Thesis, Utrecht University.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 2004. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Continuum.

- Lucchini, Lorenzo, Simone Centellegher, Luca Pappalardo, Riccardo Gallotti, Filippo Privitera, Bruno Lepri, and Marco De Nadai. 2021. “Living in a Pandemic: Changes in Mobility Routines, Social Activity and Adherence to COVID-19 Protective Measures.” Scientific Reports 11: 24452. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04139-1.

- Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Macfarlane, Robert. 2012. The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- Mehta, Vikas. 2019. “Streets and Social Life in Cities: A Taxonomy of Sociability.” Urban Design International 24 (1): 16–37. doi:10.1057/s41289-018-0069-9.

- Mermet, Anne-Cécile. 2017. “Global Retail Capital and the City: Towards an Intensification of Gentrification.” Urban Geography 38 (8): 1158–1181. doi:10.1080/02723638.2016.1200328.

- Middleton, Jennie. 2010. “Sense and the City: Exploring the Embodied Geographies of Urban Walking.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (6): 575–596. doi:10.1080/14649365.2010.497913.

- Middleton, Jennie. 2018. “The Socialities of Everyday Urban Walking and the ‘Right to the City.” Urban Studies 55 (2): 296–315. doi:10.1177/0042098016649325.

- Moran, Robyn, Karen A. Gallant, Fenton Litwiller, Catherine White, and Barb Hamilton-Hinch. 2020. “The Go-Along Interview: A Valuable Tool for Leisure Research.” Leisure Sciences 42 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1080/01490400.2019.1578708.

- Neuts, Bart, and Dominique Vanneste. 2018. “Contextual Effects on Crowding Perception: An Analysis of Antwerp and Amsterdam.” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 109 (3): 402–419. doi:10.1111/tesg.12284.

- Newman, David. 2006. “The Lines That Continue to Separate Us: Borders in Our 'Borderless’ World.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (2): 143–161. doi:10.1191/0309132506ph599xx.

- Peck, Jamie, Nik Theodore, and Neil Brenner. 2013. “Neoliberal Urbanism Redux?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (3): 1091–1099. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12066.

- Pelzer, Peter. 2012. “Nieuwe Perspectieven op Fietscultuur: Een Conceptuele en Empirische Verkenning van Fietscultuur in Amsterdam en Portland.” Tijdschrift Vervoerswetenschap 48 (4): 7–23.

- Popp Monika. 2012. “Positive and Negative Urban Tourist Crowding: Florence, Italy.” Tourism Geographies 14 (1): 50–72. doi:10.1080/14616688.2011.597421.

- Pison, Werner. 2017. “Fietsbeleving van Studenten in de Binnenstad van Utrecht: De Maartensbrug en de Viebrug.” Urban Geography Master Thesis, Utrecht University.

- Rabbiosi, Chiara. 2015. “Renewing a Historical Legacy: Tourism, Leisure Shopping and Urban Branding in Paris.” Cities 42: 195–203. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.07.001.

- Rodaway, Paul. 1994. Sensuous Geographies: Body, Sense, and Place. London: Psychology Press.

- Sane, Vivek, and Komal Chopra. 2014. “Analytical Study of Shopping Motives of Young Customers for Selected Product Categories with Reference to Organized Retailing in Select Metropolitan Select Cities of India.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 133: 160–168. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.181.

- Sennett, Richard. 2018. “The Open City.” In In the Post-Urban World: Emergent Transformation of Cities and Regions in the Innovative and Global Economy, edited by Tigran Haas and Hans Westlund, 97–106. London: Routledge.

- Simpson, Paul. 2017. “A Sense of the Cycling Environment: Felt Experiences of Infrastructure and Atmospheres.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (2): 426–447. doi:10.1177/0308518X16669510.

- Spierings, Bas. 2013. “Fixing Missing Links in Shopping Routes: Reflections on Intra-Urban Borders and City Centre Redevelopment in Nijmegen, The Netherlands.” Cities 34: 44–51. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.06.004.

- Spierings, Bas, and Henk van Houtum. 2008. “The Brave New World of the Post-Society: The Mass-Production of the Individual Consumer and the Emergence of Template Cities.” European Planning Studies 16 (7): 899–909. doi:10.1080/09654310802224702.

- Spierings, Bas. 2006. “Cities, Consumption and Competition: The Image of Consumerism and the Making of City Centres.” Human Geography PhD Thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen.

- Spinney, Justin. 2006. “A Place of Sense: A Kinaesthetic Ethnography of Cyclists on Mont Ventoux.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24 (5): 709–732. doi:10.1068/d66j.

- Stevenson, Nancy, and Helen Farrell. 2018. “Taking a Hike: Exploring Leisure Walkers Embodied Experiences.” Social & Cultural Geography 19 (4): 429–447. doi:10.1080/14649365.2017.1280615.

- Stratford, Elaine, Gordon Waitt, and Theresa Harada. 2021. “A Relational Approach to Walking: Methodology, Metalanguage, and Power Relations.” Geographical Research 59 (1): 91–105. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12400.

- Te Brömmelstroet, Marco. 2014. “De Choreografie van een Kruispunt: Naar een Gebruiksgeoriënteerde Ontwerplogica voor Kruispunten.” Paper presented at the Colloquium Vervoersplanologisch Speurwerk, Eindhoven, November 20–21.

- Ter Haar, Francella, and Frank Quix. 2021. Retail Postcorona: Impactanalyse Jan/Feb 2021. Den Haag: Retail Agenda.

- Van der Mark, Borre. 2020. “Druktebeleving in de Utrechtse Binnenstad: Een Kwalitatief Onderzoek naar de Invloed van COVID-19 en Fysieke, Sociale en Persoonlijke Factoren op de Beleving van Drukte van Studenten die in de Binnenstad van Utrecht Wonen.” Urban Geography Master Thesis, Utrecht University.

- Van den Berg, Pauline, Hamza Larosi, Stephan Maussen, and Theo Arentze. 2021. “Sense of Place, Shopping Area Evaluation, and Shopping Behaviour.” Geographical Research 59 (4): 584–598. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12485.

- Van der Spek, and Noor Scheltema. 2015. “The Importance of Bicycle Parking Management.” Research in Transportation Business & Management 15: 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.rtbm.2015.03.001.

- Van Duppen, Jan, and Bas Spierings. 2013. “Retracing Trajectories: The Embodied Experience of Cycling, Urban Sensescapes and the Commute Between ‘Neighbourhood’ and ‘City’ in Utrecht, NL.” Journal of Transport Geography 30: 234–243. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.02.006.

- Van Melik, Rianne, and Bas Spierings. 2020. “Researching Public Space: From Place-Based to Process-Oriented Approaches and Methods.” In Companion to Public Space, edited by Vikas Mehta, and Danilo Palaz, 16–26. London: Routledge.

- Von Schönfeld, Kim Carlotta, and Luca Bertolini. 2017. “Urban Streets: Epitomes of Planning Challenges and Opportunities at the Interface of Public Space and Mobility.” Cities 68: 48–55. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.04.012.

- Waitt, Gordon, Elaine Stratford, and Theresa Harada. 2019. “Rethinking the Geographies of Walkability in Small City Centers.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (3): 926–942. doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1507815.

- Wunderlich, Filipa Matos. 2008. “Walking and Rhythmicity: Sensing Urban Space.” Journal of Urban Design 13 (1): 125–139.

- Zukin, Sharon. 1998. “Urban Lifestyles: Diversity and Standardisation in Spaces of Consumption.” Urban Studies 35 (5-6): 825–839. doi:10.1080/0042098984574.

- Zukin, Sharon, Valerie Trujillo, Peter Frase, Danielle Jackson, Tim Recuber, and Abraham Walker. 2009. “New Retail Capital and Neighbourhood Change: Boutiques and Gentrification in New York City.” City & Community 8 (1): 47–64. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6040.2009.01269.x.