Abstract

The ‘compact city’ implies a return to the urban morphology of the nineteenth-century city, one in which most people walked, predominantly for utilitarian purposes. This article, however, details a leisure practice—the bourgeois promenade—as it unfolded in Stockholm. Employing a diverse set of texts and visual sources the article seeks to understand how this genteel urban practice was enabled and performed in the midst of a growing working-class population with which they shared the streets. It suggests that new street lighting and smoother pavements redirected vision from the ground to the people around, opening up for walking practices that foregrounded the visual over other senses—one being the bourgeois promenade. It further highlights the multiple rhythms of the promenade and the upper middle class’ efforts to create hierarchies of walking on city pavements and in urban parks. In sum, the article shows that leisure mobility was central to the very idea of nineteenth century urban life. Meanwhile, its exclusive character cautions against the one-sided imaginaries of strolling and consumption in today’s endeavours to recreate the compact city.

Introduction

The compact city implies a return to the urban morphology of the nineteenth-century city, easily covered by foot. Over recent decades, many European cities have been making efforts to densify and recreate nineteenth-century urbanity. In Stockholm, for example, in the 1980s, the long tendency of suburban development further away from the city was succeeded by a process of densification of the city centre and just beyond. For the first time in over a hundred years, population growth in the city centre exceeded that of the suburbs (Nilsson Citation2003). This ‘urban renaissance’ is complex, but one of its features is new urban planning ideals that appreciate the traditional city and its dense grid pattern. Stockholm’s latest comprehensive plans (Översiktsplan 1999 Citation2000; Promenadstaden: Översiktsplan för Stockholm Citation2010; Översiktsplan för Stockholms stad Citation2018) share the ambition to ‘build the city inwards’ and promote densification in the urban core and a few regional cores. The compact city that will supposedly be the result of this planning strategy is expected to bring about shorter (walkable, ‘bikeable’) distances and a better basis for public transport to compete with cars. Meanwhile, the ‘wounds’ created by modernist planning—as Stockholm’s then urban planning commissioner put it in 2008—will allegedly be healed. To recreate a denser, more coherent city on par with nineteenth-century Stockholm, the commissioner argued, would not only make it possible to cover it by foot; it would create meetings, bring people together and counter ‘insecurity, dissatisfaction and segregation.’ (Alvendal Citation2008)

Efforts to recreate the compact city are sided by those to revitalise streets: through superblocks, parklets, or summer pedestrian streets, for example, cities aim to create streets ‘for people’ instead of (car) traffic (Bertolini Citation2020; Prytherch Citation2022). Like the compact city ideal, these efforts—in many ways laudable in their ambition to rethink streets—are occasionally informed by nostalgic ideas about nineteenth-century streets as home to cosmopolitan diversity and democratic potential (Brill Citation1989; Ladd Citation2020). Yet the historiography of streets as public space, once dominated by narratives of loss, recently includes conflict and negotiation. To be sure, streets were, in the twentieth century, deprived of their multifunctional character and role as a social space for play, commerce, protest, and meaningful interaction as they were increasingly turned into traffic arteries and taken over by cars (Norton Citation2008; Loukaitou-Sideris and Ehrenfeucht Citation2009; Blomley Citation2011; Mackintosh Citation2017; Rooney Citation2018). That is not to say that nineteenth-century (pre-car) streets were places of harmony—they were, as Loukaitou-Sideris and Ehrenfeucht (Citation2009, 5) put it, ‘contested sites where rights and access were not guaranteed.’ Inspired by this literature, this article revisits the streets of nineteenth-century Stockholm, focusing on a quintessential leisure mobility practice in the original compact city, the bourgeois promenade.

Urban historians have identified a decline of the ‘walking city’ in the second half of the nineteenth century, as tramways stretched distances beyond comfortable walking, or due to a cultural preference for suburban life (Warner Citation1978; Jackson Citation1985). Within a context of growing cities and the availability of new means of public transport, Simon Sleight (Citation2016, 89) argues, ‘the journey to work on foot was no longer a near-universal experience, and the city limits moved outside the easy reach of pedestrians.’ Yet, in many cities, such as in Stockholm, real suburbanization set in later. Despite a three-folding of the population in fifty years (from 93,000 in 1850 to 300,000 in 1900), most dwellers remained within a 2–3 km radius of the city centre. Although a multitude of vehicles existed, few of them were available to ordinary residents. In short, then, most people walked, and streets were ‘places where people from all backgrounds mixed.’ (Pooley Citation2021, 232) However, if most people walked, people engaged in a variety of walking practices. Whereas studies of contemporary walking have distinguished between different purposes for walking (for exercise, to get to some place, to acquire knowledge and indeed the purposeless stroll) (Wunderlich Citation2008), walking among visitors and locals, or walking alone or in groups (Weilenmann, Normark, and Laurier Citation2014), historians have traced class-based distinctions of walking, grounded in whether people walked by choice or by necessity.

Working-class dwellers—the ‘walking class’, as Sleight (Citation2016, 89) aptly calls it—walked out of necessity. As the nineteenth century progressed, however, middle-class urbanites—mimicking their social betters of the aristocracy—connected walking with recreation. In the eighteenth century, few respectable urbanites would walk for pleasure; nevertheless, by the year 1900, strolling had become ‘a standard middle-class, urban leisure activity across the [European] continent.’ (Bryant, Readman, and Burns Citation2016, 2) With the availability of new means of transport, walking became a choice rather than a necessity—but, importantly, this regarded only the moneyed classes. When forced to share the streets, social groups sought distinction by adopting distinctive forms of appearance, including clothes, posture, and manners (Bedarida and Sutcliffe Citation1980)—and, we can add, ways of walking. Hence, if purposeful and utilitarian forms of walking dominated urban streets and pavements, many middle-class men and women in Europe and beyond engaged in a leisurely-oriented walking practice that is the subject of this article: the bourgeois promenade (cf. Scobey Citation1992; Domosh Citation1998; White Citation2006). It was, Peter K. Andersson (Citation2018, 288) argues, ‘the culmination of an urban development that had turned walking from a mode of conveyance to a method of self-presentation.’

As a leisure practice in the ‘original’ compact city, the promenade provides a lens through which we can raise questions about the role of recreational mobility in today’s densification efforts and related new approaches to street design. Beyond such an interpretative ambition across time, the article contributes in two ways. Firstly, it adds to the rich historical scholarship on the bourgeois promenade a case study of Stockholm. Secondly, it suggests avenues along which historical studies can contribute to mobilities scholarship by addressing features that are otherwise often ignored or missed. It should be stressed that the aim of the article is not to make a substantial empirical contribution or provide any radically new interpretation of the bourgeois promenade. Using Stockholm as illustration, the article brings out features of the transatlantic bourgeois promenade and discusses them in relation to common approaches and understandings within the mobilities scholarship.

The ‘mobilities turn’ (Sheller and Urry Citation2006) has spawned a growing interest to inquire into walking beyond its frequency, spatial patterns, and as a means to get from A to B. Cultural geographers, social anthropologists and other mobilities scholars have made valuable efforts to map the sensations, rhythms and material mediation of mundane, everyday walking practices (Michael Citation2000; Ingold and Vergunst Citation2008; Wunderlich Citation2008; Edensor Citation2010; Middleton Citation2010, Citation2018; Lorimer Citation2011; Kärrholm et al. Citation2017; Martınez Citation2022). Peter Merriman (Citation2014, 168) notes a preference within much mobilities studies for mobile methods (e.g., go-alongs, bikealongs, video ethnography) due to their alleged ability to bring scholars closer to their research subjects and more efficiently capture the fleeting nature of bodily engagements with mobility that elude representation. This is, argues Merriman (Citation2014, 175–176), a false sense of ‘first-handedness’ and accuracy, since one’s sensations and affects are not necessarily the others’. What is more, the immediacy of mobile methods risks coming at the expense of losing broader contextual understandings, such as the relationship between infrastructures, materialities and embodied movements or how broader discourses around regulation and proper conduct shape mobility practices. Historical studies of mobility, Merriman (Citation2014, 182) argues, are particularly apt at capturing such ‘broader discourses and discursive contexts.’ Merriman’s (Citation2007) and Tim Cresswell’s (Citation2006) historically informed analyses of mobility are good testaments to that. While acknowledging that different methods and approaches certainly have their particular strengths and weaknesses, this article aims to exemplify how historical inquiry can enable mobilities scholars to see things in new or different ways.

Methodologically, the article sets out to capture an historical urban walking practice by probing a diverse set of texts and visual sources: memoirs, city guides, photographs, paintings, newspaper articles, and archive sources. Although it is admittedly a challenge for the historian to capture affects and embodied experiences the same way in situ inquiries and mobile methods can (Spinney Citation2009; Bissell Citation2010; Degen and Rose Citation2012), I hope to show that it can uncover and usefully historicise key concerns of contemporary mobilities studies, such as collectively held meanings of mobility practices (Jensen Citation2006); how such practices are shaped by and produce urban rhythms (Edensor Citation2010; Middleton Citation2010); and social inclusions and exclusions (Cresswell Citation2010).

The article focuses on the bourgeois promenade as it unfolded in the nineteenth century in some of its key sites in Stockholm, namely Norrbro and its close surroundings. Opened in 1807, Norrbro served multiple functions. As a bridge positioned between the Royal Palace and a monumental square, Gustav Adolfs torg, it was an important ceremonial site. From the 1830s—with the opening of a bazaar (1839) and the adjacent Strömparterren (1832), an urban park hosting music pavilions and cafés—Norrbro developed into a popular site for commerce, recreation and entertainment. It was the only connection between what was still the commercial centre of the city (Old Town) with Norrmalm, the district that would soon take over that role—a ‘mercantile compass needle’ (Tjerneld Citation1988, 239) with lots of pedestrians and other traffic. Together with a few adjacent streets and Kungsträdgården, another nearby urban park, Norrbro and its pavements were the stage, spatial truncation and the material basis of the bourgeois promenade.

What follows is three episodes, each seeking to capture different aspects of the bourgeois promenade as part of city life in the nineteenth century. The first episode argues that new street lighting and smoother pavements redirected vision from the ground to the people around, opening up for walking practices that foregrounded the visual over other senses—one being the bourgeois promenade. The second episode goes further into the upper middle class’ efforts to create hierarchies of walking on the city’s pavements. The third episode engages an analysis of the multiple rhythms of the promenade, including also long-term, generational fluctuations. In the conclusion, we revisit the question of the usefulness of the historical approach to mobilities studies and, based on the example of the nineteenth-century bourgeois promenade, discuss recreational mobility in contemporary compact cities.

Eyes off the ground

Nobody in this world—that is Stockholm’s world of promenading—can but thankfully acknowledge the enlightenment, which now prevail on Norrbro every evening. … I believe to have found that, to the same extent that you see less with the eye, you see more with the foot. In the former Obscurant period, the eye despaired of recognizing any of the objects it encountered, and therefore the foot endeavoured so much more to acquaint itself with the [surface conditions]; now, on the other hand, the eye, fooled by the dazzling light, wants to recognize everything and everyone, carriages and those who live in them, those walking and standing…

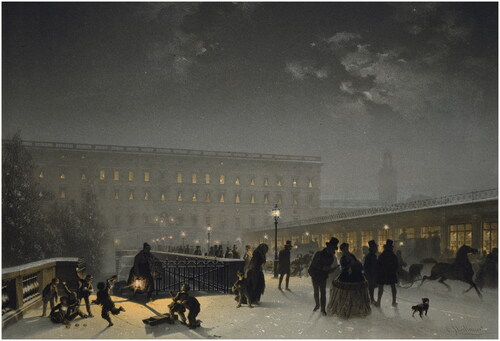

In his humorously written Stockholmska promenader, Swedish librarian and publicist Peter Adam Wallmark (Citation1815) described how the newly introduced reflector lanterns at Norrbro—of French origin, the ‘réverbère’ shone much brighter than traditional lanterns—had changed the relationship between foot and eye, giving priority to the latter. Equipped with elevated pavements when built in 1807, Norrbro was also the first place in Stockholm to display this Parisian novelty. Norrbro and its surroundings remained key sites for innovation. There, gas street lighting was trialled in 1853, a year before its wider introduction in the central parts of Stockholm. With few lamps rather far apart (15–30 meters), to a present day observer they provided guiding light rather than proper street illumination, but to contemporaries they were a modern exclusivity that made an evening or night-time stroll practical (Nerman Citation1894, 60–61) (see ). Around 1880, Kungsträdgården and Norrbro were among the first places to be lit up, on private initiative, by electric arcs; a large-scale municipal introduction of electric street lighting did not arrive in Stockholm until the next century (Garnert Citation2006; Kaijser Citation1987).

Figure 1. Norrbro during the evening, 1860–1865. Lithograph by Carl Johan Billmark. Stockholm City Museum, SSM 10535. People of style use the gas-lit pavements, seemingly undisturbed by the children playing nearby. An older woman, lighting her way with a lantern, comes up the stair from Strömparterren. Due to the snow-covered surface, the roadway is occupied by horse- or human-drawn sledges. In the background is the Royal castle and on the opposite side, Norrbro’s popular bazaar, where monied people could dress up according to the latest fashion.

This section draws on previous scholarship to suggest that Wallmark’s idea—that environmental transformations promote some senses over others—should be taken seriously. The introduction of pavements, like the implementation and improvement of street lighting—and the wider urban modernization of which they were a part—have commonly been seen as managerial responses to very real urban problems. We can use Stockholm as an example. As industrialisation took off in the mid-nineteenth century, Stockholm turned from a shipping and trading town into Sweden’s unchallenged industrial centre. As people flocked to the city, exacerbating health and environmental problems, the urban elite initiated a thorough modernisation of the city. Increasingly centralised administrative bodies created new infrastructure systems for water provision, drainage, waste management, street lighting, as well as major changes to Stockholm’s overall physical layout. Streets were levelled out and provided with pavements, gutters, and smoother surfaces. At the turn of the century, citizens of Stockholm could look back at remarkable changes that made their lives safer, cleaner, and more comfortable than a few decades before (Selling Citation1970; Gullberg Citation1998).

Writing within a tradition of liberal governmentality, Chris Otter (Citation2002) highlights how these and other material innovations contributed to a primacy of vision among the senses. Measures to improve the air quality in cities, the introduction of plate glass in shop windows, and the implementation of smoother road surfaces were, in his view, part of a ‘massive mobilization of material resources required to fashion cities into spaces within which civil conduct could be both secured and publicly displayed.’ (Otter Citation2002, 1) By ridding the streets of stench, dirt, and annoying noise, people could develop vision as the privileged sense through which to judge their own and others’ civility. In this interpretation, street lighting and smooth street surfaces made up a ‘bourgeois visual environment’ in which ‘sight can prevail, civil conduct be exposed to view [and] reserve and distance maintained.’ (Otter Citation2002, 3) Tim Ingold (Citation2004, 326–327) similarly proposes that street improvements and the establishment of smooth pavements—uniform, clean, smooth-surfaced, and well-lit—made vision dominant to other sensory impressions and turned pedestrians’ ‘visual vigilance’ off the ground to the people around them.

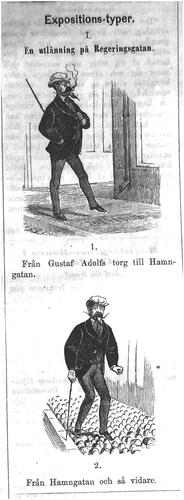

Turning to Stockholm, with a few exceptions—the city’s quaysides and Norrbro among them—the city had few pavements prior to the establishment of the street paving administration in 1845. Some streets had large, somewhat raised flat stones (borgmästarstenar) dispersed as islands in a sea of cobblestones to help pedestrians avoid the mud (Cramér Citation1983, 83–84; Dufwa Citation1985, 10). Besides a few streets in the city centre, cobblestone pavements were the norm, and press reports complained how such pavements were a ‘torture’ and ‘torment’ to the feet (see, e.g. ‘Kommunalfrågor’ Citation1862). Pushed by such concerns, the administration increasingly opted for other materials such as paving stones and asphalt. By the turn of the century, cobblestone pavements were rarely used in the streets of Stockholm (Emanuel, Citation2023). As elsewhere, pavements had smoother paving than the roadways (Dufwa Citation1985, 49–56; Fröman Citation1897, 272–273). In fact, pavements were not just, or even primarily, a matter of traffic safety. They lent pedestrians comfort and decency, and smooth surfaces allowed for walking without constant attention paid to the ground. Like improved street lighting during the darker hours, smoother pavements permitted daytime pedestrians to put down their feet with more confidence, making each step less of a balancing act, and—as suggested by caricatures of foreign visitors to Stockholm’s industry exhibition in 1866—lending them a more civil appearance (see ).

Figure 2. Illustration by Gustaf Wahlbom, published in the comic magazine Söndags-Nisse, June 10, 1866. In this cartoon, Wahlbom picked up on the geographically uneven quality of pavement surfaces. Published in connection to Stockholm’s industry exhibition of 1866, he portrayed two foreign ‘exhibition-types’, differentiated by their appearances as they walked down Regeringsgatan. Close to the exhibition area, where Regeringsgatan had pavement made of smooth paving stones, the foreigner could stroll with pride; further down the street, however, the cobble-stoned pavement quickly turned his cane from a symbol to a supporting tool.

Vision was indeed at the centre of two iconic walking practices of the nineteenth century: flaneuring and promenading—yet pedestrians’ visual attention was geared very differently in these two cases. By mid-century, claimed Claude Gerard—a pseudonym for Aurora Lovisa Ljungstedt, one of Sweden’s first detective novelists—‘the passion’ to stroll had been perfectly naturalised in Stockholm. The capital’s many flaneurs were easily recognizable: ‘their gait and posture, their attention to everything’ revealed ‘absolute idleness.’ However, despite their ‘seemingly drowsy eyes’, they registered everything, particularly anything out of the ordinary that happened—indeed, such occasions, Gerard/Ljungstedt argued, ‘are necessary for their being, give life and colour to it.’ Without an office to appear in, their office was everywhere, Norrbro their ‘headquarters.’ (Gerard Citation1857) While such a distanced gaze at the urban spectacle is a trademark of the flaneur (Epstein Nord Citation1991), the bourgeois promenade was—as we shall see in the next section—about seeing and being seen. Moreover, the ‘ideal of decorous, self-disciplined movement’, David Scobey (Citation1992, 216) argues, sets promenading against the ‘improvisatory, voyeuristic’ qualities of flaneuring.

Compared to both promenading and flaneuring, Miles Ogborn (Citation1998, 113–114) found that mundane, everyday walking in eighteenth-century London involved ‘a less formalised engagement with public space, characterised by an intense sense of the individual experience of the city and a feeling of being in it, if not fully part of the crowd.’ This ‘liberal’ form of walking, as Patrick Joyce calls it—which prevailed in late-nineteenth-century Stockholm—fits well with Otter’s idea about individual reserve and distance. As I argue elsewhere (Emanuel Citation2023), norms and regulations to secure pavement circulation reflected not only ambitions to speed up pedestrian mobility at the expense of subsistence-driven usages of pavements, it also facilitated undisturbed walking, allowed pedestrians to avoid sensory overload and close interaction with strangers (cf. Mackintosh Citation2017). All in their own distinct ways, these different walking practices relied on novel ways to balance the senses to fellow urbanites and the material basis of walking.

Scholars of mobilities (Kärrholm et al. Citation2017; Martínez Citation2022) have suggested approaching walking as a ‘socio-technical assemblage’, thus highlighting the ‘embodied, material and technological relations and their significance for engaging with everyday urban movement on foot.’ (Middleton Citation2010, 575). Such assemblages are understood as some combination of walking subject, mediating mundane technologies such as shoes and clothes (Michael Citation2000), and things pushed, pulled or carried along, be it trolleys, plastic bags, luggage, or mobile phones (Cochoy, Hagberg, and Canu Citation2014; Holton Citation2019). In these treatments of walking, the larger material context—the everyday urban environment—appears, not necessarily unimportant, but mute. I propose that historical inquiry can help to appreciate the agency of urban infrastructures that risk, as they cease to be new, slipping into the background. It can help in uncovering how these second natures are integral to and crucial for the slow-moving transformations of mobility practices. For example, if we acknowledge the multi-sensory nature of walking (Middleton Citation2010), various sorts of street improvements helped shift the relative weight and direction of different sensorial registers—in turn, as we will see below, facilitating the development of new forms of sociability.

Promenades of distinction

Towards Norrbro, what diverse sorts of professions and faces! … There hovered a young, enchanting, most handsomely dressed lady, in bloom and muslin past the stairs, where the beggar’s wife, hardly covered by her rags, gnawed on a mouldy piece of bread. There—but here a young man crossed my mind. He came up on the bridge from Helgeandsholmen. The face beautiful, but what traces of destruction! The dark hair in wild disorder, wilder was the disorder in the eyes, the hat too small for the head, badly roughed up, the clothes too. Then he walked briskly across the bridge, in the clear sunlight, through the motley crowd. A young girl, rosy to cheeks and dress, looked at him and—laughed. How childish! A large gentleman, with a bit stiff appearance, looked at him and bounced. … The unhappy youth went through the crowd; where he went, heads were hastily turned after him, then again hastily gone. He walked, walked—toward the precipice of perdition, I thought;—he disappeared. The crowd closed murmuringly behind him…

Fredrika Bremer was a prominent novelist and a pioneer of the Swedish Suffragette movement. Writing for the poetic calendar Linnea Borealis in 1840 (extract reproduced in 'Vid fyrtio år' 1840), she captured Norrbro as a place where people of all sorts mixed, yet where manners and appearance helped maintain social hierarchies. As working-class people flocked to cities, and crowded living conditions and low living standards made them turn to the streets for leisure, daily chores, and pure subsistence, nineteenth-century streets became places where people of all classes met and interacted (Bedarida and Sutcliffe Citation1980; Stansell Citation1982). Some scholars have argued that this made streets and boulevards democratic. Others have highlighted how people of esteem and resources worried how the ‘anonymous and transient urban mass’ or the presence of the ‘wrong’ kind of people risked diminishing their neighbourhood’s reputation and even property values (Dennis Citation2008, 142–144).

This section situates the bourgeois promenade in Stockholm alongside earlier scholarship, not least the work of Chad Bryant (Citation2016) on Prague and in particular that of David Scobey (Citation1992) on New York. The bourgeois promenade enabled members of the new urban middle-class to display their social standing. Civil servants, merchants, industrialists, and members of the intelligentsia in early nineteenth-century Prague, Chad Bryant (Citation2016, 57–59, 85) writes, ‘strolled in order to establish their credentials as urban, middle-class elites when an emerging liberalism challenged privileged, absolutist rule and the weight of tradition.’ In these times of rapid urban change, streets were emblematic of urban disorder. By investing the streetscape with ritual order, David Scobey (Citation1992, 221) argues, the promenade gave legitimacy to urban inequalities. The promenade ‘mapped out an elite public-within-the-public, inscribing class and cultural hierarchy across the common landscape in New York.’

Like other stylized performances of bourgeois life, the promenade depended on the material urban environment and the labour that went into maintaining it (Otter Citation2002). Smooth street surfaces and, in particular, the establishment of pavements, were pivotal. Due to their smoother paving, raised level, and adjacent gutter, pavements provided a more comfortable alternative to the roadways with their mud, manure and water-filled potholes—pedestrians could avoid ‘wading in dirt’ and ‘throng with horses and vehicles.’ (Cederschiöld Citation1827, cited in Fröman Citation1897, 262) From the onset, pavements became a matter of prestige and a measure of a district’s level of sophistication. Pavements tended to be established in centrally-located districts first, and only later in others. The residents of the outer districts felt under-serviced. They pointed to the lack, or poor state, of pavements as indicative of the little consideration authorities had for the needs of ‘the poor and people of lesser means’ in their district (Sign. A.J.A-r Citation1878). In Stockholm, as in London, street improvements tended to centre on those streets that were ‘valued enough to be paved, cleansed, lit, made safe—in short “civilised”.’ (Ogborn Citation1998, 90)

Early pavement construction enabled uptown residents to engage in the Parisian-style promenade outside dedicated city parks such as Kungsträdgården. Norrbro’s pavements and bazaar gave it the reputation as ‘the most distinguished promenade spot’ in Stockholm: a place for ‘rendez-vous’ among ‘dandies’ and ‘beau-mondes’ alike (as well as ‘demimondes’), and where genteel couples announced their engagement by means of a joint promenade (Nerman Citation1894, 60; Selander and Selander Citation1920, 121–123; Linder Citation1924, 293–298). Pavements in fact helped determine the geography of the bourgeois promenade. Stretching a few blocks from Norrbro, the typical promenade included other ‘fashionable’ streets such as Drottninggatan, Fredsgatan, and—once it had pavements—Regeringsgatan (Stridsberg Citation1895, 22). In their memoirs, the Selander brothers, sons of an astronomy professor, recollected how their promenades stretched only as far up Drottninggatan as it was equipped with pavements (Selander and Selander Citation1920, 121–123)—pointing to how integral pavements were to the practice. Yet other aspects also factored in. For example, the bazaar with its bookstores, cigar shops and popular cafés made Norrbro’s western side the promenade of the prominent; the other pavement was, as one author puts it, ‘for simple transport’ (Tjerneld Citation1988, 248)—resembling the ‘fashionable’ and ‘shilling’ sides of New York’s Broadway (Scobey Citation1992, 214). A mid-day stroll at ‘one of Norrbro’s pavements’ made one male columnist feel ‘warm at heart’ by the co-presence of ‘so much youth and so much beauty’ (‘Ditt och datt’ Citation1867.)

The promenade as a performance of a distinctive bourgeois culture depended not only on pavements; it was aesthetic, moral and social as much as it was material. Bryant (Citation2016, 71) accounts for some noticeable attributes and norms of conduct codified in advice books. Next to tobacco bags, ‘specially designed walking hats’, and women’s gloves, walking sticks and umbrellas were the bourgeois strollers’ substitutes of the dual sword worn by their aristocrat predecessors. Instructed to keep a distance of a least two metres from new acquaintances, intimate friends and family members walked arm-in-arm. ‘Idleness’, writes Bryant, ‘combined paradoxically with an upright stance and stiffness in limbs, distinguished the walk.’ Scobey (Citation1992, 215–219) furthermore identifies three defining elements of the ritual of the promenade: constant, decorous movement, representing a release of motion from motive; the displacement of social discourse into visual spectacle—members of a respectable public brought together through inscribing distance; and the formal exchange of recognitions and greetings. This is how we can understand Bremer’s scolding comment of the young women in the section’s opening scene—‘How childish!’—because talking too loud, staring or, as in this case, laughing, was not in line with the norm among the bourgeois public to maintain a distanced attitude.

Without assuming that the practice was identical everywhere, or stable over time, findings from Stockholm are similar enough to dare speak of a transatlantic practice. Swedish etiquette books—often translations of foreign versions—similarly stressed the importance of a steady posture and raised head to signal ‘dignity and grace.’ The general advice of a ‘natural’ and ‘genuine’ style of walking was supplemented by numerous dos and don’ts: not too fast nor too slow, steady, uniform, natural, hands and head in a firm position (Kullberg Citation1828, 70–71; Wenzel Citation1845, 18–23). Although actual behaviour was probably suppler than these manuals suggest, it is clear that the ‘naturalness’ they promoted was in fact rather controlled. In line with this, historians have traced a late nineteenth-century ‘crisis’ in middle-class masculinity, when distinguished men increasingly employed their body and posture rather than dress and character to differentiate themselves from women as well as less respectable men (Andersson Citation2018).

Upper- and middle-class women were increasingly visible in urban public space in the late nineteenth century, although conservative discomfort continued to circumscribe their full participation in public life (Ryan Citation1990; Walkowitz Citation1992). According to Scobey (Citation1992, 217–221), the promenade provided a relatively safe space for genteel women’s appearance in public, including courting and flirting, which was nevertheless strictly monitored. In theory, the promenade was available to all—any urban dweller could (try to) appropriate the expected manners. Yet, as it involved expensive clothing, mid-day spare time, and since the ‘norms of polite culture’ were in fact difficult to learn for those outside bourgeois culture, the promenade was in fact ‘barricaded with class barriers.’ That said, working-class urbanites and the larger public played a crucial role, Scobey (Citation1992, 221–222) argues, as witnesses to ‘the spectacle of hierarchy.’ While both women and workers (and people of colour) could develop walking behaviours that run counter to the bourgeois norm of the promenade (Domosh Citation1998), the classed and gendered nature of the promenade was strong.

Memoirs point to how, in mid-nineteenth century Stockholm, young women in particular should avoid walking the city streets alone if they cared about their reputation, and more so during the darker hours due to the risks of unwelcome suitors and sexual assault (Selander and Selander Citation1920, 163; Nerman Citation1894, 59–61). Women’s clothing and interaction with others was meticulously monitored. Having described the cumbersome dressing process prior to a promenade, and the drying, cleaning and brushing afterwards, a Stockholm upper middle-class woman remarked: ‘Luckily the ladies did not go out every day.’ (Wrangel Citation1927, 261). Etiquette books urged women to control their visual attention. ‘A lady should’, according to one such book, ‘when in the street…discipline her eyes, so that they do not friskily stray off and betray their owner’s will for conquest or something even worse.’ (Correus Citation1905)

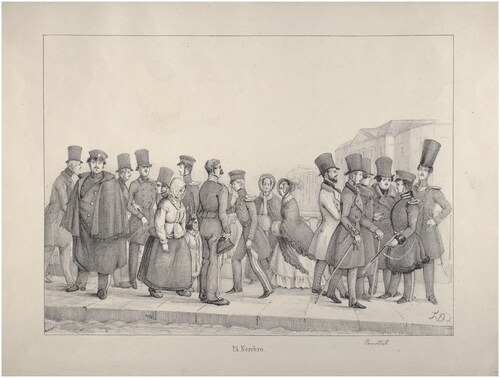

As soon as pavements appeared in Stockholm in the mid-nineteenth century, a process of regulating their use began. While the right of access for the walking public was secured, other usages—in particular those of the poor and working-class—were restrained (cf. Ehrenfeucht and Loukaitou-Sideris Citation2007; Mackintosh Citation2017). The following decades saw protracted debates about the appropriate use of pavements, and legitimate usage was not only formally regulated but also socially constructed (Emanuel Citation2023). ‘Ordinary’ urban dwellers felt pushed aside by more prominent strollers, as indicated by the impression of a visitor to Norrbro in the spring of 1843. ‘Stockholm’s fashionables of both sexes wandered back and forth on the spacious pavements, and in spite of their width, many less distinguished pedestrians had to step aside into the filth of the street below, in order to leave space for ladies, clothed according to the latest fashion journal and gentlemen with or without uniform, accompanying them.’ (Anon Citation1843) To be sure, social hierarchies contributed to different levels of confidence and sense of belonging on the pavements, as is also suggested in .

Figure 3. Lithography by Fritz von Dardel (1817–1901). Stockholm City Museum, SSM F 107316. In this sea of upper and middle-class men and a few women in elegant attire, speaking and saluting each other on Norrbro in the 1840s, a single woman in mundane clothes, her child in hand, takes a subservient pose, face down, seemingly hoping to pass unnoticed.

To reconnect with mobilities scholarship, the classed and gendered attributes, clothes and bodily and visual codes of the bourgeois promenade added up to socio-technical assemblages of great complexity. These assemblages, it must be stressed, were shot through by social class. Kärrholm et al. (Citation2017) argue that walking has a ‘seriality’ to it, meaning that while many engage in different sorts (series) of walking, the practitioners do not know each other or form a social group or a community. The bourgeois promenade—we hear it already by the term—was different. Although not all practitioners were acquainted (or even bourgeoisie), participation in the practice reflected social class—there was indeed a strong and class-based practice community. In this sense, the bourgeois promenade and how it has been understood by historians poses a challenge to mobilities scholars who approach mobility from a non-representational perspective. If mobility practices are seen as made up by fleeting, bodily mediated and pre-cognitive behaviour, if mobile encounters are governed by some flat interactional order (Goffman Citation1963; Jensen Citation2006), then how can we take on board social standing and everyday urban politics—what Middleton (Citation2018, 311) refers to as ‘the politics of the social dimensions of walking’—in our analysis? Because although many present-day mobile practices may have a serial character—different sorts of commuting, for example—others appear to involve stronger community ties grounded in socio-economic status. This feature is perhaps stronger for leisure activities and playful or recreational mobility practices such as urban running, skateboarding, or kayaking.

Rhythms of promenading

At four o’clock in the morning, one or two mysterious figures appear in its [Norrbro’s] pavements; there is a young man with crude boots and a terrible toilet, who sneaks home after a less well-spent night, some rag or bone collector, who early in the morning goes out to earn a few pennies, some longshoreman, who woke up from his rough night camp on a staircase or in a street corner, and who now slowly goes to work. Later, towards 6 o’clock, one or two better dressed people seem to take their morning walk and the worker is off to work. The city now gradually awakens from its nocturnal rest; maidens with baskets on their arms and hurrying seamstresses soon appear and are succeeded by the businessmen… Towards 1 o’clock, when the elegant world has been able to get dressed, it takes its pre-dinner promenade, and a couple of hours later a large part of Stockholm’s bachelors appear in flocks of 3 to 4, pondering about where to have their coffee and punch. Towards seven o’clock, the spectacle-seeking audience…hurries across, then, if the weather is fine, Norrbro is occupied by a multitude of walkers of all classes, until later in the evening, only one or two gentlemen, who have happened to forget about time, and one or two ladies of some dubious conductconstitute the only walkers. After a while, all movement stops for a few hours, and then the cycle restarts again at dawn.

In his city guide to Stockholm, Olof Abraham Ericsson (Citation1852, 14) described how different sorts of pedestrians substituted each other on the smooth paving of Norrbro. Everybody walked, but apparently according to different schedules. Many contemporaries noted the class-bound daily rhythm of Norrbro and other places (Lundin Citation1904, 31, 37; Selander and Selander Citation1920, 121–123; Sjögren Citation1923, 169–175). Norrbro was ‘the liveliest part of Stockholm’, remembered Gurli Linder of the 1870s, where one would find ‘restless ambition next to the noble or simple mike, there is the promenade place of luxury and elegance, here is the vanity market.’ Yet, although ‘celebrities in the aristocracy, politics, science, art and the business world’ could be spotted at certain hours, in the evenings, the audience was of a ‘simpler quality’ (Linder Citation1924, 297–298).

A focus on a specific place enables us to appreciate its rhythmicity as an outcome of the practices that produce it. As a multi-functional space, it should come as no surprise that various sorts of flows merged in Norrbro. Across the day, it was a place of varying intensities of moving and staying (Normark Citation2006) (see ). Writing about rhythms of walking and the production of place, Tim Edensor (Citation2010) attends that ‘[s]paces and places…possess distinctive characteristics according to the ensemble of rhythms that interweave in and across place to produce a particular temporal mixity of events of varying regularity.’ Repetitive, collective choreographies produce ‘situated rhythms through which time and space are stitched together.’ If the resulting ‘place ballet’ (Seamon Citation1980) appears to be stable, Edensor (Citation2010) argues, it is partly an illusion: its stability comes from the ‘serial reproduction of its consistencies, through the reproduction of the changing same.’ Hence, the Norrbro promenade, for example, was distinguishable and made tangible through repetitive performances at a similar time of day and place, and importantly so, by a particular ‘sort’ of people. This social dynamics of place ballets is, it seems, ignored in in situ-style analysis, with its preference for interactional over institutional orders. Historical analysis is more attuned to those enduring patterns of ‘stability’—although, as we will see, these are also subject to (longer term) change.

Figure 4. Norrbro around 1900. Unknown photographers. Stockholm City Museum, SSM CF 484 and Fa 49085. In these two photographs, varying shutter times, etc., render the landscape, infrastructure, and everyday practices in quite different ways. In the photograph above, movements are frozen and all street users, whether still or moving, are given equal weight to infrastructure. The photograph on the next page, on the other hand, reveals the relative stability of the urban landscape, street and buildings, compared to various intensities of moving and staying. Faster moving traffic are all but erased, and some pedestrians have left traces of their paths, whereas only those that were still or relatively so (a police officer in mid-street, two fellows at the left hand side) come out as more than vague silhouettes.

Class-differentiated schedules and what we could call a social construction of time contribute to the rhythms of mobility, whether they are daily, weekly, seasonal or even longer term. The bourgeois promenade was bound in space and manners, but it was equally bound in time to a few early afternoon hours—as seen in the quote from Ericsson’s city guide in the opening of this section, and as further illustrated by Scobey’s (Citation1992, 214) phrase the ‘canonical hour’ (11–15) of the promenade. Were upper middle-class residents to take part in the conformational play of the promenade, they had to take the opportunity and visit Norrbro, Kungsträdgården and the surroundings when their peers were there; hence, the daily rhythmicity of the practice.

In other respects, mobility patterns varied over the week, by the season or in the very long time span of generations. We can exemplify with promenading in Kungsträdgården. A royal park and the oldest in the city, Kungsträdgården (literally, the king’s garden) in fact preceded Norrbro as a prominent promenade spot, originally for the aristocracy. Opened to the public in 1783, the ordinance regulating its use reveal its classed character: servants, maids and older children had to stay outside when their masters frequented the promenade; ball games and other activities that disturbed the strollers were strictly forbidden. A new ordinance in 1802 prohibited similar categories of people from using the park as a short cut and asked visitors to grant others ‘proper homage, civility and docility…according to their social standing and worth.’ (Georgii Citation1802) In the early 1820s, the park was replaced by a gravel ground for military exercise, leaving only the alleys for strolling (Asker Citation1986, 37–43). As the park was restored in the 1860s and equipped with cafés and restaurants, sculptures and fountains, the Kungsträdgården stroll became, according to one scholar, ‘the quintessence of the urban bourgeois life style.’ (Nolin Citation2006, 111–113) Blanche’s café opened in 1868 and soon developed into a natural meeting point and a cultural centre with live music. It also contributed to seasonal variations of promenading. In the summer, when the most distinguished residents had left the city for their nearby summer residences or resorts, visitors and locals of lower ranks flocked to the western alley close to Blanche’s, leaving the eastern alley almost empty. During the fall, however, when the café had fewer guests, distinguished strollers tended to withdraw to the eastern alley—leading one observer to distinguish between a ‘summer’ and a ‘winter promenade.’ (Sign. Hilarius Citation1869; ‘Den gångna veckan’ Citation1871.)

Writing twenty years later, in 1889, the pseudonym Sylvestre found Kungsträdgården the only place in Stockholm that could qualify as a Parisian-style ‘boulevard’, defined as ‘a small world in itself, very interesting, very lively, but very limited’ and characterised by ‘[s]mall conversations, consisting of small news from the theatres, the ateliers, from the literary world.’ This was Kungsträdgården—during the week, that is, because on Sundays, it transformed into ‘Stockholm’s great promenade, the cosmopolitan gathering point for [people of all districts] and of all classes. … Kungsträdgården a Sunday afternoon. Two long, wavy giant streams in the wide tree-lined avenues. Thousands of greetings to the right and to the left, clinking spurs, light nods, discrete smiles, flairs [cold and warm].’ Sylvestre repeated his assessment the next year: belonging to the distinguished world most days of the week, on a beautiful Sunday afternoon, the promenade of Kungsträdgården knew no class boundaries, but rather displayed the ‘democracy of the future, where the excellence elbowed with the artisan.’ (Sign. Sylvestre Citation1889; ’Våren i Stockholm’ Citation1890)

Hence, to participate in the weekday promenade was premised by the availability of time and resources, work flexibility and, ultimately, social position. Chad Bryant distinguishes between strolling practices among the nobility and the bourgeoisie in early nineteenth century Prague: while the former strolled during the week, the latter did so only on Sunday afternoons and holidays, ‘thus underscoring a division between work and leisure during the week, not to mention the merits of labour as opposed to inherited luxury.’ (Bryant Citation2016, 71). Workers developed their own ‘plebeian promenades’ (Scobey Citation1992). In Prague, Bryant (Citation2016, 73) mentions, when workers took up middle-class strolling practices, the better-offs moved to new places.

In Stockholm, as suggested by Sylvestre’s analysis above, the weekly pattern of differentiation between nobility and middle-class promenading stretched towards the end of the century into a partial democratization of the (Sunday) promenade. Promenading in Stockholm also migrated with urban development and as new social groups joined the practice. Closer to the end of the century, Norrbro appears to have lost its attraction as a spot for promenading. One reason might have been that the centre of commerce had migrated further into Nedre Norrmalm, leading to the closure of the bazaar in 1902; another was the increasing levels of traffic over Norrbro. Pedestrians who aimed to cross the street had to navigate several streams of traffic before reaching the other side. As one observer put it in Citation1891: ‘It is really important to…watch out and seize the moment’—hence pointing to how visual attention again shifted, relatively speaking, now away from social interaction and gazing to handling and navigating traffic (‘Trafiken på Stockholms gator’ Citation1885; ‘Hufvudstaden: Vasabron’ Citation1891). In the same process, pavements became increasingly about staying safe from traffic—as we tend to understand them today—and other road users increasingly wanted to expel pedestrians to pavements (‘Om åkande och färdande på Stockholms gator’, Citation1862; Sign. Östermalmsbor Citation1899).

In the process, Norrbro became less appealing for self-representation and sociality, and in the new century, Stockholm’s promenading centre of gravity shifted towards Strandvägen. A product of the grandiose urban plans of the 1850s, Strandvägen was completed just before the opening of Stockholm World’s Fair 1897—connecting the city centre with the festive area on Djurgården. This boulevard, 72 metres wide, harboured traffic lanes as well as a wide, tree-lined avenue for walking, riding and cycling in the middle. Strandvägen was the foremost of several boulevards circumventing the transformed district of Östermalm. With the exclusive waterfront residences of the business elite lined up along the street, in the new century, it became the most popular promenade spot. According to several testimonies, the promenade along Strandvägen was more ‘democratic’ than the bourgeois promenade at Norrbro, with people of all classes taking part (Andersson and Monastra Citation1997, 69–70).

This possible change in the ‘nature’ of the promenade in the early twentieth century will not be further assessed here; suffice it to say that, following a practice (here promenading), long term socio-spatial changes beyond the immediacy of the ‘place ballet’ come into light. The place-specific analysis helps to unravel the immediacy and rhythmicity of short and relatively shorter time spans: seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks and even seasons. These are valuable insights, but can easily become out of date. Following a practice, on the other hand, helps to understand rhythms of the longer term, such as how the practice moves in space and changes its social basis, yet is less capable of capturing some of the fine-grained intricacies of mobilities. More broadly conceived, this points to how historical studies can help appreciate the strengths as well as the weaknesses of ‘presentist’ mobilities studies. Methodological choice must of course ultimately be determined by what we seek to understand.

Conclusion

Mention recreational or leisure mobility in nineteenth-century Europe and most people will conjure up images of better-off urbanites temporarily leaving the city for peri-urban excursions to parks and amusements, trips to spas or health resorts, or possibly late-version Grand Tours, rites de passage and educational trips across the continent. As a city surrounded by water, in mid-century Stockholm, steam boats considerably facilitated the urban elite to acquire summer houses along the shores outside the city proper and reach the spas that were established a bit further afield (Johansson Citation1991, 196–219). Yet this article focused on an intra-urban leisure mobility practice: the bourgeois promenade, which was indeed central to the very idea of nineteenth-century, middle-class urban life. Through its three episodes, the article traced different traits of the bourgeois promenade in Stockholm and beyond. Moreover, it pointed to ways in which historical studies can contribute to mobilities studies—including and beyond, as Peter Merriman (Citation2014, 182) suggests, helping to understand relevant ‘broader discourses and discursive contexts.’

The first episode pointed to infrastructures as an often forgotten or underestimated part of socio-material assemblages of mobility. New forms of street lighting, pavements and paving surfaces not only made it easier and more comfortable to walk on city streets, day and night, they were also, as previously argued by historians of governmentality, crucial to strengthening vision as the dominant sense through which urbanites experienced their city. Hence, while acknowledging the relative stability of infrastructures and the overall urban landscape compared to the transient character of mobility—a feature that is also conveyed by the photography of the period (see )—they should not be understood as mute or mere background, as they often are in presentist mobilities studies. Historical analysis helps to appreciate the agency of infrastructure—here in terms of how they contributed to shifting urban sensescapes—which is most apprehensible when they are new but later easily slips out of view.

While relatively stable, the urban landscape does change, as do the everyday practices that give places their character. In this sense, a historical take on mobility practices adds more long-term movements to the multiple and overlapping rhythms that make up a place. As seen in the third episode, the bourgeois promenade featured weekly as well as seasonal variations, some of which were socially defined. For example, participation depended on dress and manners, but also the availability of time. Moreover, towards the end of the century and into the new, the practice itself gradually shifted in social composition and migrated to new places. This comes closer to Merriman’s (Citation2014) suggestion that history helps position the understandings of mobile rhythms so presciently captured in presentist approaches in their wider social and spatial contexts.

The second episode highlighted how historical studies, while having difficulty capturing the immediacy of mobile interactions, are particularly useful in uncovering socially grounded hierarchies of mobility. The primacy of vision influenced contemporary walking practices. Yet, as pedestrians refocused their attention from the ground to the surroundings, as suggested by Ingold (Citation2004), they did so in different ways. Vision and socially defined rhythms co-constructed the bourgeois promenade, which was all about seeing and being seen, the small nods of confirmation; but they also depended—as demonstrated by Scobey (Citation1992)—on the co-presence of non-participants. It played out, quite literally, in front of everyone’s eyes—yet not everybody had the means, socially or culturally, to participate as anything more than on-lookers. Hence, the bourgeois promenade shaped and displayed a hierarchical urban space.

We started out with today’s ambitions to recreate compact cities and restore the streets of pre-car cities. What interpretative power does the historical example of the bourgeois promenade have with respect to understanding present-day recreation and leisure mobility in today’s densification efforts? Let us start by acknowledging the difficulty of comparing in any straightforward manner phenomena that are more than a hundred years apart without giving due attention to context and developments in-between. That being said, a first observation is that the bourgeois promenade never existed in isolation. It happened in the midst of urban life in its totality, and while sufficiently distinct for us to speak of ‘the promenade’, it filtered in with multiple other practices, many of which were ‘utilitarian.’ Perhaps particularly in dense urban environments, and the compact cities that are presently sought for, recreational and ‘purposeful’ mobility is not easily separated, neither conceptually nor in space.

The findings presented here corroborate those of other authors who have highlighted the tensions and conflicts of nineteenth-century streets. They firmly refute the idea that streets without (or with fewer) cars will automatically turn into vivid places accessible to all. While freeing up space and creating new openings, how these are utilised is an open question. As socially produced public spaces, streets are likely to remain—as they always have been—sites of joy and opportunity but also contention around design and regulatory frameworks of access and usage as well as practices on the ground (Mitchell Citation2003). That said, programming matters and can be more or less inclusive. It appears as if the exclusive character of the bourgeois promenade—one of the most distinct leisure mobility practices of nineteenth-century cities—warrants caution against the often one-sided imaginaries of strolling and consumption in many of today’s endeavours to build streets for people rather than traffic. Pedestrian streets, for example, with their cafés and small shops might be vivid and economically as well as environmentally sound, but they are not necessarily welcoming to all. Considering the already hefty processes of gentrification in compact cities, an accommodating approach to designing for leisure and recreational mobility appears as crucial.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his gratitude to Mattias Qviström and Nik Luka as convenors of the workshops from which this article emanates, as well as their co-editor of this special issue, Daniel Normark, for their continuing support. He would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and advise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- “Den gångna veckan.” 1871. Aftonbladet, September 25.

- “Ditt och datt.” 1867. Dagens Nyheter, January 26.

- “Hufvudstaden: Vasabron.” 1891. Fäderneslandet, August 5.

- “Kommunalfrågor.” 1862. Aftonbladet, April 28.

- “Om åkande och färdande på Stockholms gator.” 1862. Aftonbladet, January 21.

- “Trafiken på Stockholms gator.” 1885. Figaro, March 22.

- “Våren i Stockholm.” 1890. Aftonbladet, May 17.

- “Vid fyrtio år.” 1840. Aftonbladet, December 24.

- A.J.A-r. 1878. “no title.” Dagens Nyheter, December 21.

- Alvendal, Kristina. 2008. “Stockholm blir en promenadstad.” Svenska Dagbladet, October 15.

- Andersson, Peter K. 2018. “The Walking Stick in the Nineteenth-Century City: Conflicting Ideals of Urban Walking.” The Journal of Transport History 39 (3): 275–291. doi:10.1177/0022526618783937.

- Andersson, Magnus, and Nino Monastra. 1997. Stockholms årsringar: En inblick i stadens framväxt. Stockholm: Stockholmia.

- Anon. 1843. “no title.” Norrköpings Tidningar, December 15.

- Asker, Bertil. 1986. Stockholms tekniska historia 2: Stockholms parker. Stockholm: LiberFörlag.

- Bedarida, Francois, and Anthony Sutcliffe. 1980. “The Street in the Structure and Life of the City: Reflections on Nineteenth-Century London and Paris.” Journal of Urban History 6 (4): 379–396. doi:10.1177/009614428000600402.

- Bertolini, Luca. 2020. “From ‘Streets for Traffic’ to ‘Streets for People’: Can Street Experiments Transform Urban Mobility?” Transport Reviews 40 (6): 734–753. doi:10.1080/01441647.2020.1761907.

- Bissell, David. 2010. “Passenger Mobilities: Affective Atmospheres and the Sociality of Public Transport.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (2): 270–289. doi:10.1068/d3909.

- Blomley, Nicholas K. 2011. Rights of Passage: Sidewalks and the Regulation of Public Flow. New York: Routledge.

- Brill, Michael. 1989. “Transformation, Nostaliga, and Illusion in Public Life and Public Place.” In Public Places and Spaces, edited by Irwin Altman and Ervin H. Zube, 7–29. Boston: Springer.

- Bryant, Chad, Paul Readman, and Arthur Burns. 2016. Walking Histories, 1800–1914. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bryant, Chad. 2016. “Strolling the Romantic City: Gardens, Panoramas, and Middle-Class Elites in Early Nineteenth-Cenutry Prague.” In Walking Histories, 1800–1914, edited by Chad Bryant, Paul Readman and Arthur Burns, 57–85. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cederschiöld, Pehr Gustaf. 1827. Om sundhetstillståndet i Stockholm och medlen till desz förbättrande. Stockholm: Zacharias Haeggström.

- Cochoy, Franck, Johan Hagberg, and Roland Canu. 2014. “The Forgotten Role of Pedestrian Transportation in Urban Life: Insights from a Visual Comparative Archaeology (Gothenburg and Toulouse, 1875–2011).” Urban Studies 52 (12): 1–20. doi:10.1177/00420980145447

- Correus, Carl. 1905. Umgängeslifvets lexikon: Praktisk uppslagsbok för god tons bevarande inom det moderna samlifvets alla förhållanden. Malmö: Envalls bokh.

- Cramér, Margareta. 1983. “Gatubeläggning i Stockholm.” In Sankt Eriks årsbok, 77–106. Stockholm: Samfundet S:t Erik.

- Cresswell, Tim. 2006. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York: Routledge.

- Cresswell, Tim. 2010. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1068/d1.

- Degen, Monica Montserrat, and Gillian Rose. 2012. “The Sensory Experiencing of Urban Design: The Role of Walking and Perceptual Memory.” Urban Studies 49 (15): 3271–3287. doi:10.1177/0042098012440463.

- Dennis, Richard. 2008. Cities in Modernity: Representations and Productions of Metropolitan Space, 1840–1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Domosh, Mona. 1998. “Those ‘Gorgeous Incongruities’: Polite Politics and Public Space on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century New York City.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88 (2): 209–226. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.00091.

- Dufwa, Arne. 1985. Stockholms tekniska historia: Trafik, broar, tunnelbanor, gator. Stockholm: Kommittén för Stockholmsforskning.

- Edensor, Tim. 2010. “Walking in Rhythms: Place, Regulation, Style and the Flow of Experience.” Visual Studies 25 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1080/14725861003606902.

- Ehrenfeucht, Renia, and Anastasia. Loukaitou-Sideris. 2007. “Constructing the Sidewalks: Municipal Government and the Production of Public Space in Los Angeles, California, 1880–1920.” Journal of Historical Geography 33 (1): 104–124. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2005.08.001.

- Emanuel, Martin. 2023. “Pavement Publics in Late Nineteenth-Century Stockholm.” Journal of Transport History. 1–32.

- Epstein Nord, Deborah. 1991. “The Urban Peripatetic: Spectator, Streetwalker, Woman Writer.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 46 (3): 351–375. doi:10.2307/2933746.

- Ericsson, Olof Abraham. 1852. Promenader genom Stockholm: Tio vuer i stålstick med upplysande text. Stockholm: P. Adolf Huldberg.

- Fröman, Otto. 1897. “Stockholms gator, afloppstrummor och planteringar.” In Stockholm: Sveriges hufvudstad. D. 2, edited by Erik Wilhelm Dahlgren, 247–294. Stockholm: J. Beckman.

- Garnert, Jan. 2006. Norrbro, Gustav Adolfs Torg och Strömparterren: Belysningshistoria och ljusarkitektur. Stockholm: Trafikkontoret, Stockholms stad.

- Georgii, Pehr Eberhard. 1802. Ordning för dem, som wilja promenera uti Kongl. Maj:ts trägård wid Jacobi kyrka. Stockholm: Office of the Governor of Stockholm.

- Gerard, Claude. 1857. “Dagdrifverier och drömmerier.” Aftonbladet, September 9.

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. London: Free Press of Glencoe.

- Gullberg, Anders. 1998. “Nätmakt och maktnät: Den nya kommunaltekniken i Stockholm 1850-1920.” In Den konstruerade världen, edited by Arne Kaijser and Pär Blomkvist, 105-129. Eslöv: Symposion.

- Hilarius. 1869. “Stockholms-bref.” Aftonbladet, July 31.

- Holton, Mark. 2019. “Walking With Technology: Understanding Mobility-Technology Assemblages.” Mobilities 14 (4): 435–451. doi:10.1080/17450101.2019.1580866.

- Ingold, Tim, and Jo Lee Vergunst. 2008. Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Ingold, Tim. 2004. “Culture on the Ground: The World Perceived Through the Feet.” Journal of Material Culture 9 (3): 315–340. doi:10.1177/1359183504046896.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. 1985. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jensen, Ole B. 2006. “‘Facework’, Flow and the City: Simmel, Goffman, and Mobility in the Contemporary City.” Mobilities 1 (2): 143–165. doi:10.1080/17450100600726506.

- Johansson, Ingemar. 1991. Stor-Stockholms bebyggelsehistoria: Markpolitik, planering och byggande under sju sekel. Stockholm: Gidlund.

- Kaijser, Arne. 1987. “Energisystem i konkurrens: Gas kontra elektricitet.” In I teknikens backspegel: Antologi i teknikhistoria 1987, edited by Bosse Sundin and Boel Berner, 151–178. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Kärrholm, Mattias, Maria Johansson, David Lindelöw, and Inês A. Ferreira. 2017. “Interseriality and Different Sorts of Walking: Suggestions for a Relational Approach to Urban Walking.” Mobilities 12 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1080/17450101.2014.969596.

- Kullberg, Herman Anders. 1828. Walda komplimenter, eller Anwisning att i sällskaper och lifwets wanliga förhållanden tala höfligt och paszande samt uppföra sig anständigt. Axel Petre: Linköping.

- Ladd, Brian. 2020. The Streets of Europe: The Sights, Sounds, and Smells That Shaped Its Great Cities. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Linder, Gurli. 1924. På den tiden: Några bilder från 1870-talets Stockholm. Stockholm: Bonnier.

- Lorimer, Hayden. 2011. “Walking: New Forms and Spaces for Studies of Pedestrianism.” In Geographies of Mobilities: Practices, Spaces, Subjects, edited by Tim Cresswell and Peter Merriman, 19–33. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia, and Renia Ehrenfeucht. 2009. Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation Over Public Space. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lundin, Claës. 1904. En gammal stockholmares minnen 1. Stockholm: Geber.

- Mackintosh, Phillip Gordon. 2017. Newspaper City: Toronto’s Street Surfaces and the Liberal Press, 1860–1935. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Martínez, Soledad. 2022. “‘Nobody ever Cuddles any of Those Walkers’: The Material Socialities of Everyday Mobilities in Santiago de Chile.” Mobilities 17 (4): 545–564. doi:10.1080/17450101.2021.1999776.

- Merriman, Peter. 2007. Driving Spaces: A Cultural-Historical Geography of England’s M1 Motorway. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Merriman, Peter. 2014. “Rethinking Mobile Methods.” Mobilities 9 (2): 167–187. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.784540.

- Michael, Mike. 2000. “These Boots Are Made for Walking: Mundane Technology, the Body and Human-Environment Relations.” Body & Society 6 (3-4): 107–126. doi:10.1177/1357034X00006003006.

- Middleton, Jennie. 2010. “Sense and the City: Exploring the Embodied Geographies of Urban Walking.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (6): 575–596. doi:10.1080/14649365.2010.497913.

- Middleton, Jennie. 2018. “The Socialities of Everyday Urban Walking and the ‘Right to the City’.” Urban Studies 55 (2): 296–315. doi:10.1177/0042098016649325.

- Mitchell, Don. 2003. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: Guilford Press.

- Nerman, Gustaf. 1894. Stockholm för sextio år sedan och dess framtid: En skildring. Stockholm: Bonnier.

- Nilsson, Lars. 2003. “The Return to the City: Twentieth Century Urban Development in Sweden.” In Reclaiming the City: Innovation, Culture, Experience, edited by Marjaana Niemi and Ville Vuolanto, 47–62. Helsingfors: Finnish Literature Society.

- Nolin, Catharina. 2006. “Stockholm’s Urban Parks: Meeting Places and Social Contexts from 1860 to 1930.” In The European City and Green Space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850–2000, edited by Peter Clark, 111–126. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Normark, Daniel. 2006. “Tending to Mobility: Intensities of Staying at the Petrol Station.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2): 241–252. doi:10.1068/a37280.

- Norton, Peter D. 2008. Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ogborn, Miles. 1998. Spaces of Modernity: London’s Geographies, 1680–1780. New York: Guilford Press.

- Östermalmsbor. 1899. “Polisen och gatutrafiken.” Aftonbladet, December 29.

- Otter, Chris. 2002. “Making Liberalism Durable: Vision and Civility in the late Victorian City.” Social History 27 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/03071020110094174.

- Översiktsplan 1999. 2000. Stockholm: Stadsbyggnadskontoret, Stockholms stad.

- Översiktsplan för Stockholms stad. 2018. Stockholm: Stadsbyggnadskontoret, Stockholms stad.

- Pooley, Colin. 2021. “Walking Spaces: Changing Pedestrian Practices in Britain since c. 1850.” The Journal of Transport History 42 (2): 227–246. doi:10.1177/0022526620940558.

- Promenadstaden: Översiktsplan för Stockholm. 2010. Stockholm: Stadsbyggnadskontoret, Stockholms stad.

- Prytherch, David L. 2022. “Reimagining the Physical/Social Infrastructure of the American Street: Policy and Design for Mobility Justice and Conviviality.” Urban Geography 43 (5): 688–712. doi:10.1080/02723638.2021.1960690.

- Rooney, David. 2018. Spaces of Congestion and Traffic: Politics and Technologies in Twentieth-Century London. London: Routledge.

- Ryan, Mary P. 1990. Women in Public: Between Banners and Ballots, 1825–1880. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Scobey, David. 1992. “Anatomy of the Promenade: The Politics of Bourgeois Sociability in Nineteenth-Century New York.” Social History 17 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1080/03071029208567835.

- Seamon, David. 1980. “Body-Subject, Time-Space Routines, and Placeballets.” In The Human Experience of Space and Place, edited by A. Buttimer and D. Seamon, 148-165. London: Croom Helm.

- Selander, Nils, and Edvard Selander. 1920. Två gamla Stockholmares anteckningar. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Selling, Gösta. 1970. Esplanadsystemet och Albert Lindhagen: Stadsplanering i Stockholm åren 1857–1887. Stockholm: Stockholms stadsarkiv.

- Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2): 207–226. doi:10.1068/a37268.

- Sjögren, Arthur. 1923. Drottninggatan genom tiderna: Kulturhistoriska anteckningar. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Sleight, Simon. 2016. “Rites of Passage: Youthful Walking and the Rhythms of the City, c.1850–1914.” In Walking Histories, 1800–1914, edited by Chad Bryant, Paul Readman and Arthur Burns, 87–112. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spinney, Justin. 2009. “Cycling the City: Movement, Meaning and Method.” Geography Compass 3 (2): 817–835. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00211.x.

- Stansell, Christine. 1982. “Women, Children, and the Uses of the Streets: Class and Gender Conflicts in New York City, 1850–1860.” Feminist Studies 8 (2): 309–335. doi:10.2307/3177566.

- Stridsberg, O. A. 1895. En gammal Stockholmares hågkomster från stad och skola. Stockholm: Fahlcrantz & K.

- Sylvestre. 1889. “Det vackra Stockholm.” Aftonbladet, June 1.

- Tjerneld, Staffan. 1988. Stockholmsliv: Hur vi bott, arbetat och roat oss under 100 år. Bd 1, Norr om Strömmen. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Walkowitz, Judith R. 1992. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London. London: Virago.

- Wallmark, Peter Adam. 1815. Stockholmska promenader. Stockholm: R. Ecksteins tryckeri.

- Warner, Sam Bass. 1978. Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870–1900. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Weilenmann, Alexandra, Daniel Normark, and Eric Laurier. 2014. “Managing Walking Together: The Challenge of Revolving Doors.” Space and Culture 17 (2): 122–136. doi:10.1177/1206331213508674.

- Wenzel, Gottfried Immanuel. 1845. Den äkta gentlemannen, eller grundsatser och regler för god ton och sannt lefnadsvett i umgängeslifvets särskilda förhållanden: En handledning för unga män, till att göra sig omtyckta i sällskapslifvet och af det täcka könet. Göteborg: Bonnier.

- White, Cameron. 2006. “Promenading and Picnicking: The Performance of Middle-Class Masculinity in Nineteenth-Century Sydney.” Journal of Australian studies 30 (89): 27–40. doi:10.1080/14443050609388090.

- Wrangel, Tekla. 1927. Från forna tider: Hörsagor och personliga minnen. Stockholm: Bonnier.

- Wunderlich, Filipa Matos. 2008. “Walking and Rhythmicity: Sensing Urban Space.” Journal of Urban Design 13 (1): 125–139. doi:10.1080/13574800701803472.