Abstract

Background Internal fixation has become the preferred treatment for type-C pelvic ring injuries, but controversies persist regarding surgical approach and surgical technique.

Patients We evaluated 101 consecutive patients with type C1-C3 pelvic ring injuries who had been treated with standardized reduction and internal fixation techniques.

Results Our findings suggest a correlation between excellent reduction followed by sufficient fixation of the pelvic ring and functional outcome. Unsatisfactory reduction (displacement > 5 mm), failure of fixation, loss of reduction and a permanent lumbosacral plexus injury were the commonest reasons for an unsatisfactory functional result. All 40 patients with an associated lumbosacral plexus injury showed at least some evidence of neurological recovery. 14 underwent complete neurologic recovery. 8 had only sensory deficits and the remaining 18 also had motor deficits at the final followup. Complications were rare, but some of them were severe: loss of reduction in 8%, malunion in 10%, deep wound infection in 2%, and a lesion of the L5 nerve root in 1%.

Interpretation Our results suggest that special attention should be paid to preoperative planning, reduction of the fracture, decompression of the nerve roots, and fixation of the most severe sacral fractures. Our results seem to favor internal fixation of displaced (> 10 mm) and unstable rami fractures and symphyseal disruptions in conjunction with posterior fixation, to achieve better stability of the whole pelvic ring.

Unstable pelvic ring disruptions result from high-energy trauma and are often associated with multiple concomitant injuries (Rothenberger et al. Citation1978, Gilliland et al. Citation1982, Pohlemann et al. Citation1996). Bleeding, head injury, pelvic soft tissue trauma (open fractures), and primary system complications are responsible for high mortality rates (Mucha and Welch Citation1988, Burgess et al. Citation1990, Tscherne and Regel Citation1996). If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, the primary goals are to control airways, to establish adequate ventilation and to maintain circulation. The external fixation frame may play a role in partial stabilization of the pelvic ring, reducing pelvic volume, increasing tamponade, and thereby reducing bleeding (Gylling et al. Citation1985, Evers et al. Citation1989, Bircher Citation1996, Wolinsky Citation1997). Once patients are stabilized, careful assessment and definitive treatment of the pelvic ring injuries can be done.

In the 1970s, external fixation devices became popular for definitive treatment of unstable pelvic ring injuries (Slätis and Karaharju Citation1975, Gunterberg et al. Citation1978, Slätis and Karaharju Citation1980, Lansinger et al. Citation1984). Later, it became clear that an external frame applied anteriorly could not restore enough stability to an unstable (type-C) disruption of the pelvic ring to allow mobilization of the patient without risking redisplacement of the fracture (Mears and Fu Citation1980, Wild et al. Citation1982, Kellam Citation1989, Tile Citation1995, Lindahl et al. Citation1999). Thus, methods of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) were introduced (Goldstein et al. Citation1986, Kellam et al. Citation1987, Ward et al. Citation1987, Tile Citation1988, Matta and Saucedo Citation1989, Pohlemann et al. Citation1994). More recently, closed reduction and percutaneous screw fixation techniques have been developed (Ebraheim et al. Citation1987, Routt et al. Citation1995, Routt and Simonian Citation1996a). Internal fixation has become the preferred treatment for unstable posterior pelvic ring injuries (Kellam et al. Citation1987, Matta and Saucedo Citation1989, Pohlemann et al. Citation1996, Tornetta and Matta Citation1996), but the indications for fixation of the anterior pelvic ring injuries have varied (Hirvensalo et al. Citation1993, Routt et al. Citation1995, Matta Citation1996, Routt and Simonian Citation1996b).

Biomechanical studies have shown that the best stability in type-C pelvic ring fractures can be achieved by internal fixation of the posterior and anterior pelvic ring injuries (Leighton et al. Citation1991, Tile Citation1995). During recent years, our policy has been to restore the anatomy of the pelvic ring with standardized reduction and internal fixation techniques of the posterior and anterior parts of the pelvic ring. Our hypothesis was that, in addition to the posterior fixation, displaced (> 10 mm) and unstable anterior injuries with fractures of the pubic rami or symphyseal disruption, or both, require to be treated with internal fixation. For the present prospective study, we evaluated the long-term radiographic and clinical outcomes of this approach.

Patients

We evaluated 117 consecutive patients with type-C injuries of the pelvic ring, treated within 3 weeks of injury with open or closed reduction and internal fixation techniques between May 1989 and May 2000. 4 patients were excluded because of paraplegia associated with an unstable thoracolumbar fracture or rupture of the abdominal aortae, 7 died (3 within 1 month postoperatively because of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, and 4 later), and 5 patients were lost to follow-up. This left 101 patients (66 men) with a mean age of 33 (15–79) years at the time of injury.

According to Tile's (AO) classification system (Tile Citation1988, Citation1995) there were 24 type C1-1, 16 type C1-2, 40 type C1-3, 13 type C2 and 8 type C3 injuries. There were 5 types of anterior pelvic ring injuries: unilateral rami fractures, bilateral rami fractures, symphyseal disruption, and combinations of these. 4 patients had no anterior injury to the pelvic ring. There were 4 open fractures. 6 patients had a closed degloving (Morel-Lavalle) soft tissue injury on the sacrum (Helfet and Schmeling Citation1995). There were 16 concomitant acetabular fractures in 13 patients. 12 of these were transverse, 2 were anterior column, 1 was T-type, and 1 was both column fractures (Letournel and Judet Citation1993).

40/101 patients had an associated lumbosacral plexus injury. 2 patients with a type-C injury also had a concomitant thoracolumbar vertebral fracture with a partial spinal cord or cauda equinae injury, and paraparesis. 7 patients had rupture of the bladder, and all of these patients were treated operatively. No rupture of the urethra was seen in this series. The mean Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 29 (10–57) (Greenspan et al. Citation1985). 1 patient had traumatic thigh amputation and one had below-the-knee amputation because of severe soft tissue injuries and infection.

Methods

All displaced and unstable posterior pelvic ring injuries with fracture of the sacrum, dislocation or fracture dislocation of the sacroiliac joint, or fracture of the ilium were regarded as indications for open or closed reduction and internal fixation. Displaced (> 10 mm) fractures of the pubic rami or total disruption of the symphysis pubis, or both, were also treated with internal fixation. A concomitant displaced acetabular fracture was also an indication for open reduction and internal fixation (14 fractures in 12 patients). 62 of the operations were done by the first author (JL), 28 by the second author (EH), and the remaining 11 by 3 other orthopedic surgeons. Local ethical regulations relevant to clinical studies were followed.

Posterior fixation

Injuries of the posterior part of the pelvic ring were most commonly operated on first. If the initial displacement of the disruption of the symphysis pubis (diastases and/or translation) or the rami fractures were wide (> 10 mm), a subsequent anterior approach was done. Also, if displacement was > 10 mm in the anterior pelvic ring injury after posterior fixation, an anterior approach and fixation was done. One option in patients with C1-1 or C1-2 injuries was a simultaneous ORIF of both sides through two anterior approaches.

Sacral fractures were stabilized with the patient in the prone position, with one or two cannulated 7.0-mm partially threaded or fully threaded iliosacral screws () across the fracture line into the S1 vertebral body under fluoroscopic guidance (Matta and Saucedo Citation1989). The posterior longitudinal skin incision was made slightly medial to the posterosuperior iliac spine without releasing the gluteal muscles from the outer side of the iliac crest. The sacral fracture was observed and reduced with forceps. In most patients, the iliosacral screws were inserted through a separate small lateral skin incision percutaneously to avoid large soft tissue stripping on the lateral aspect of the iliac wing and wound complications. In minimally displaced lateral sacral fractures (< 10 mm), a closed reduction with forceps and percutaneous iliosacral screw fixation was done. In all patients, the screws were placed at least past the midline of the sacrum. In 1 patient with a comminuted sacral fracture, a threaded compression rod was used to anchor the injured hemipelvis to the contralateral ilium to help supplement screw fixation.

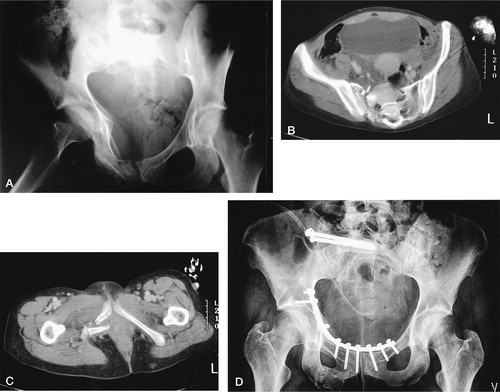

Figure 1. (A) A 33-year-old woman had a type-C1-3 injury of the pelvic ring by lateral compression injury mechanism. (B) There was a clear vertical and ventral (25-mm) dislocation in the lateral sacral fracture, and (C) a marked dislocation and shortening in the duplex rami fracture site. With the patient prone, the sacral fracture was reduced and fixed with two iliosacral screws. (D) The patient was then placed in the supine position and the duplex rami fracture with a marked medial impaction in the right side was reduced through a lower midline incision extraperitoneally and fixed with one long 3.5-mm reconstruction plate. The functional outcome was excellent at the final follow-up.

Sacroiliac dislocation and sacroiliac fracture dislocation were fixed with iliosacral screws with the patient in the prone position (), or with the patient in the supine position with anterior 3.5-mm or 4.5-mm reconstruction or DC-plates, or both, using an incision at the iliac crest and exposing the internal aspect of the wing and the sacroiliac joint (Matta and Saucedo Citation1989, Tile Citation1995). Transiliac fractures were fixed with anterior 3.5-mm reconstruction plates or screws, or both, using the same approach ().

Figure 2. (A) A 49-year-old man had a major crushing injury, sustaining a type-C3 injury to the pelvis without any injury to the anterior part of the pelvic ring. (B) The bilateral fracture dislocation of the sacroiliac joint was treated with open reduction and iliosacral screw fixation.

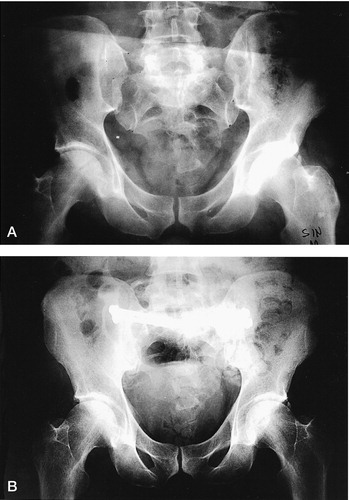

Figure 3. (A) A 19-year-old woman was injured when a tree fell on her during a storm, sustaining a type-C1-1 injury to the pelvic ring. (B) There was a marked vertical and lateral dislocation of the iliac wing. (C) She had a concomitant rupture of the bladder, which was seen in the cystografia. (D) She was operated in the early phase by suturing the rupture of the bladder and by reducing and fixing simultaneously the pubic ramus, the symphysis pubis, and the iliac wing with 3.5-mm reconstruction plates. She had no primary or late complications, and the final functional outcome was good.

Anterior fixation

Disruption of the symphysis pubis was exposed through either a vertical or a transverse Pfannenstiel's incision (Matta and Saucedo Citation1989). A vertical incision was chosen when the anterior fixation was combined with laparotomy. A transverse incision was otherwise the choice for symphyseal disruption or juxtasymphyseal fractures of the rami, for cosmetic reasons. The midline between the rectus abdominis muscles was opened and the prevesical area was exposed. The insertions of the rectus abdominis muscles were incompletely detached from the pubis on their inner aspects, whereas the lateral and outer parts of attachment were left intact.

The more lateral fractures of the superior rami were exposed through the lower midline approach by extending the dissection laterally, as described by Hirvensalo et al. (Citation1993). The dissection below the rectus muscle was continued subperiosteally and laterally on the superior ramus, following the inner aspect of the pelvic brim. The corona mortis vessels were ligated whenever they were present. The external iliac vessels, the femoral nerve, and the iliopsoas muscle were lifted slightly anteriorly with a retractor and left undisturbed. No dissection or separation of these vulnerable structures was necessary. The underlying obturator nerve and vessels entering the obturator foramen were identified and protected. By remaining close to the brim and by using subperiosteal stripping only, the risk of injuring all essential structures can be avoided. The iliopectineal fascia was detached in lateral rami fractures to facilitate exposure of the juxtaacetabular area of the superior ramus and the supraacetabular brim in the most lateral fractures. If a concomitant acetabular fracture was present, the anterior column and the quadrilateral surface could be exposed. In bilateral rami fractures, both sides were exposed.

Displaced (> 10 mm) fractures of the pubic rami were fixed internally with a curved reconstruction plate using 3.5-mm screws placed along the pelvic brim (linea terminalis) ( and ). In 2 patients, fixation of lateral fractures of the superior ramus was done with a long intramedullary 3.5-mm screw. Fixation of bilateral fractures of the rami was done either by using one long plate or by two separate plates, one on each side. In 4 patients with severe open fractures or severe comminution and osteoporosis, fixation of the anterior injury was done with an anterior external fixator. The fixator was removed after 6–10 weeks. Bladder injury was not considered a contraindication to anterior internal fixation. All 7 bladder injuries were treated operatively through the lower midline approach, within the first 24 hours. In the same operation, the anterior pelvic ring injuries were fixed with plates.

Postoperative treatment

In type-C1 injuries, mobilization with crutches was started within 1–2 days without weight bearing on the injured side, and if the associated injuries of the lower extremities allowed it. Full weight bearing was started after 8–12 weeks. The load was increased gradually, based on the fracture type and radiographic follow-up. In type-C3 injuries and in most type-C2 injuries, the walking exercises with crutches were started after 8–12 weeks depending on the type of the posterior pelvic ring injury.

Radiological evaluation

The vertical displacement in the posterior and anterior injury to the pelvic ring was measured from AP radiographs of the pelvis. Vertical displacement was measured as the difference in height of the femoral head (C1-1 and C1-2 injuries) and the superior aspect of the sacrum (C1-3 injuries) from a line perpendicular to the long axis of the sacrum on the AP radiograph (Matta and Tornetta Citation1996). The AP displacement of the posterior pelvic ring injury was determined by CT. Radiographs were taken before primary treatment, after reduction and internal fixation, and at the final follow-up. The AP displacement of the anterior pelvic fragments could not be measured reliably by CT.

The radiographic results were graded by the maximal residual displacement in the posterior or anterior injury to the pelvic ring as: excellent, 0–5 mm; good, 6–10 mm; fair, 11–15 mm; and poor, more than 15 mm (Lindahl et al. Citation1999). The evaluation was done by both authors.

Outcome evaluation

The mean follow-up was 23 (12–85) months. All 101 patients had a clinical examination with particular attention to their gait, hip motion, difficulty in sitting, tilting or obliquity of the pelvis, scoliosis, and persistent motor and sensory nerve deficiencies. Neurological examination was done from L4 distally preoperatively and postoperatively by the treating surgeon, and at the final follow-up by the first author. Motor neurological deficits of the lower extremities were graded on a 6-point scale: 0, no palpable muscle action; 1, muscle contraction palpable, produces no limb motion; 2, moves limb, but less than full range of motion against gravity; 3, moves limb segment through full range of motion against gravity; 4, muscle strength better than fair but less than normal; and 5, normal-comparable to contralateral normal limb (Chapman and Olson Citation1996).

The residual pain was graded as: no pain, mild (intermittent, normal activity), moderate (limits activity, relieved by rest), and severe (continuous at rest, intense with activity) (Majeed Citation1989). The site of pain in the pelvic ring (anterior or posterior) was recorded.

We measured the functional outcome using a scoring system described by Majeed (Citation1989) and modified by Lindahl et al. (Citation1999), which is based on clinical findings. The original scoring system was modified to focus on the outcome after an unstable fracture of the pelvic ring, and not on the handicap caused by multiple injuries. The final score for the clinical outcome was also modified specifically to take account of the outcome after the pelvic injury. Thus, the patient's ability to work was removed from this assessment, giving a maximal total score of 80 points for each patient for comparison of the outcome of different types of fracture. The outcome was graded by total points as: excellent, 78–80 points; good, 70–77 points; fair, 60–69 points; and poor, less than 60 points (Lindahl et al. Citation1999).

The Hannover pelvic outcome score was also used for the comparison (Pohlemann et al. Citation1996). In this system, the ratings of the radiological result and the clinical result are assessed as one score on a 7-point scale, where the maximum of 7 points represents an excellent result, 6 points is a good result, 4 and 5 points represent a fair result, and 2 and 3 points mean a bad or poor result. In this system, urological deficiencies also are taken into account. The outcome scorings were done by the first author.

We investigated urological and sexual deficiencies by interview. The urological findings were classified as increased frequency of micturation, pain on micturation, disturbance of bladder function, and incontinence. Males were evaluated for erectile dysfunction and females for dyspareunia (Pohlemann et al. Citation1996). Evaluation of lower urinary tract function with urodynamic studies was not done in patients without clear urological symptoms.

Statistics

All statistical evaluations were performed using SPSS 11.0.1 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The multiple logistic regression analysis (Cox regression) with the forward stepwise method was used in order to detect independent factors that might be correlated to the outcome. Both crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals are reported, and values different from 1 are considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Posterior and anterior fixations were done in 78 of 101 patients. 74 anterior fixations were internal and 4 were external. 20 patients had posterior fixation only; 4 of these patients (type-C3 injuries) had no anterior injury and 16 had a minimally displaced (< 10 mm) anterior injury. In 3 patients, only anterior fixation was done because the initial displacement of the posterior pelvic ring injury was minimal (< 5 mm). 8 had a bilateral type-C posterior injury and internal fixation was done on both sides in 6 of these patients, and the anterior injuries were fixed with plates. 108 iliosacral screws were inserted in 55 patients and 17 of these screws (13 patients) were inserted percutaneously without open reduction of the fracture.

103 posterior internal fixations and 77 anterior fixations were done in 101 patients. The mean operative time for posterior fixation was 98 (15–325) min, and 95 (20–225) min for anterior fixation. The longest operative time included the fixation of the concomitant acetabular fracture. The mean total blood loss was 1.4 (0.1–5.0) L. 17 of the patients were operated on within 24 h of injury.

The final radiographic results were excellent in 66 patients, good in 25 patients, and fair in 10 patients (none had a poor result). The initial preoperative displacement (vertical or AP displacement) was more than 10 (10–60) mm in the posterior or in the anterior ring injury, or in both pelvic ring injuries. In 10 patients with an unsatisfactory (fair or poor) final radiological result, 6 had a failure of the primary fixation. In 4 of these patients, the fixation failed in the posterior pelvic ring, while in 2 patients it failed in the anterior pelvic ring. In 2 patients, the minimally displaced and unfixed sacral fracture dislocated more after mobilization of the patient without weight bearing on the injured site, and united in an unsatisfactory position. In 2 other patients, the position of the initially minimally displaced (< 10 mm) and unfixed anterior pelvic ring injury showed increased displacement although the posterior injury was adequately fixed.

The functional score results were excellent in 68 patients, good in 16, fair in 16, and poor in 1 patient. They were positively affected by stable anatomic reduction (). Unsatisfactory (fair or poor) functional results were associated with lumbosacral plexus injuries in 10/17 patients. In this subgroup, 3 patients had an unsatisfactory reduction result. In 1 of the 17 patients, the unsatisfactory functional result followed a nonanatomic reduction, and in 1 spinal stenosis not associated with the pelvic fracture. The only poor functional result followed traumatic thigh amputation. In 4 patients, the functional results were unsatisfactory because of late pain in the posterior part of the pelvic ring despite the fact that there had been a satisfactory radiological result. 34/101 patients had late pain problems, and in 33 of them the pain was mainly located in the posterior part of the pelvic ring.

Table 1. Functional results and final radiological resultsin the 101 patients with type-C pelvic ring injuries

All 40 patients with concomitant lumbosacral plexus injuries showed at least some evidence of neurological recovery. 14 patients had complete neurological recovery with no motor or sensory deficiencies of the lower legs at the final follow-up. All except 1 of these patients had excellent or good functional results. The patient with a poor result had pain in the posterior part of the pelvic ring. 8 patients had only a sensory defect at the follow-up, and their functional results were excellent or good. In 18 patients partial motor deficits were recognized, and 6 of these patients had chronic radicular pain in the lower leg at the final follow-up ().

Table 2. Recovery of motor neurological deficits (n = 40)

Most of the patients with an excellent or good radiographic result (78/91) had at least a good functional result. There was a significant association between the radiological and functional results (Odds ratio 4.0; 95% CI: 1–16). 13 patients with an excellent or a good radiographic result had a fair or poor functional result. The most significant factor associated with this finding was the occurrence of a symptomatic lumbosacral plexus or nerve root injury (motor deficiencies), which was observed in 8 of these 13 patients, but only in 11 of the 78 patients who had an excellent or a good radiographic and functional result (OR 9.2; 95% CI: 2.7–35.3).

There was a clear association between an excellent radiographic end result (displacement of not more than 5 mm) and functional outcome when single prognostic factors were analyzed, and also in the multifactorial analysis (). Permanent neurological injury also showed an association with final functional outcome in the statistical analysis (). On the other hand, the fracture type (C1, C2 or C3) and Injury Severity Score did not show any association with functional recovery. Female sex and age (< 33 years) were also positive prognostic factors.

Table 3. Analysis of prognostic factors associated with the functional outcome after operative treatment of pelvic fractures in a series of 101 patients. Figures within parentheses are rates

Urological deficiencies were detected in 3 men and in 2 women. 1 of these patients had increased frequency of micturation and 4 had a disturbance of bladder function. 5 male patients had erectile dysfunction. Urological and sexual deficiencies were associated with severe lumbosacral plexus injuries in 6 of the 9 patients. In 1 patient, this was probably attributable to rupture of the bladder. In 2 patients, the reason for erectile dysfunction was unclear because they had no associated neurological or urological injury.

The Hannover pelvic outcome score, which combines the radiographic and clinical results into a single score, was excellent in 43 patients, good in 38 patients, fair in 17 patients, and poor in 3 patients.

Complications were rare, but some of them were severe. After internal fixation, 8 patients had loss of reduction (). In 6 patients, this occurred in the posterior pelvic ring injury and 5 of these patients had reoperation. 3 of these patients received late operative treatment (6–12 weeks after the trauma). In all 5 patients, a clear radiological correction was achieved and the final functional result was satisfactory in 4/5 patients. In 2 patients, loss of reduction occurred in the rami fracture site, one after intramedullary screw fixation, and the other after plate fixation. Both of these patients were treated nonoperatively.

Table 4. Complications after internal fixation of type-C pelvic ring injuries (n = 101)

There were 2 deep wound infections. 1 of these developed after a severe open fracture and the other followed a closed degloving soft tissue injury on the sacrum. Both wound infections were treated surgically and the final functional results in these patients were good or excellent. There were 3 superficial wound infections which were treated nonoperatively. One L5 nerve root lesion developed after iliosacral screw penetration of the anterior superior surface of the sacrum. The L5 nerve root injury with radicular pain and weakness of dorsiflexion of the ankle and a sensory deficit corresponding to the L5 dermatome was seen before the operation. The neurological damage worsened only slightly after the operation. At the latest follow-up, the patient still had some radicular pain in the foot with physical loading. The iliosacral screws were removed 6 months postoperatively, with no effect on the radicular pain.

Discussion

The stability of the pelvic ring depends mainly on the integrity of the posterior weight-bearing sacroiliac complex. However, biomechanical studies have shown that in type-C injuries, the symphysis pubis and pubic rami are important for the overall stability of the pelvic ring, contributing approximately 40% of the total stability of the ring (Tile Citation1995). Biomechanical studies have also shown that an anterior external fixator cannot restore enough stability to an unstable type-C injury to allow secure mobilization of the patient without risk of redisplacement of the fracture (Leighton et al. Citation1991, Tile Citation1995, Citation1999). In the 1980s, this led to a change in treatment protocols and methods of ORIF of sacroiliac injuries and symphyseal disruption were introduced (Goldstein et al. Citation1986, Kellam et al. Citation1987, Ward et al. Citation1987, Tile Citation1988, Matta and Saucedo Citation1989). Moreover, several operative techniques for reduction and fixation of fractures of the pubic rami have been described (Hirvensalo et al. Citation1993, Pohlemann et al. Citation1994, Routt et al. Citation1995, Matta Citation1996, Routt and Simonian Citation1996b). Our hypothesis was that one can secure a good reduction and avoid complications by using internal fixation in the posterior and anterior pelvic ring injuries when there is a clear instability.

When analyzing the results following pelvic ring injuries, there can often be difficulties in interpretation because neurological and other concomitant injuries may affect the functional recovery. The functional scoring system described by Majeed (Citation1989) was modified specifically to take account of the outcome after pelvic injury. A good scoring system helps the comparison between different clinical series and types of fracture. In our study, the follow-up outcome evaluations were done by the same author to avoid interobserver variations. On the other hand, the functional evaluations were not blinded-and use of an independent evaluator would have been a better way of performing the follow-up evaluations. In clinical use, reporting radiological and functional results separately gives more precise information about the outcome than one single score which combines all main parameters. In the future, a validated pelvic outcome score would be helpful for comparison of results of different clinical series and treatment protocols.

Internal fixation has become the preferred method for unstable posterior pelvic ring injuries, but the question of how much residual displacement is acceptable is still controversial. Tornetta and Matta (Citation1996) suggested that 10 mm was an acceptable reduction for injury to the posterior pelvic ring, and they suggested that a more anatomic reduction of posterior injuries did not result in less posterior pain. McLaren et al. (Citation1990) and Lindahl et al. (Citation1999) reported that greater than 10 mm of residual displacement of the posterior pelvic ring was a poor prognostic sign. In the Hannover score, the outcome was graded fair if the residual posterior displacement was greater than 5 mm. However, in our study an excellent radiographic result (maximal residual displacement 0–5 mm in the posterior or anterior pelvic ring injury) showed a clear association with excellent or good functional outcome.

Iliosacral screw fixation is recommended for fixation of sacral fractures, sacroiliac dislocations and sacroiliac fracture dislocations (Matta and Saucedo Citation1989, Tile Citation1995, Matta and Tornetta Citation1996, Routt and Simonian Citation1996b). However, care must be taken when inserting cannulated screws into the sacrum medially to the sacral foramina. One L5 nerve root injury occurred in one of our patients. The most unstable and comminuted sacral fractures are clinical problems, because it might be impossible to achieve adequate stability of the pelvic ring with iliosacral screws only. Those 6 patients with secondary displacement after screw fixation were examples of this. The most severe posterior pelvic injuries require special attention and careful preoperative planning. 5 of our patients with sacral fractures did not have fixation because the initial displacement was minimal. The posterior injury pattern was evaluated incorrectly as being more stable than it was, which resulted in worsening of the position in 2 patients although the anterior injury to the pelvic ring was fixed with plates. This supports the use of internal fixation also in highenergy minimally displaced sacral fractures. Minimally displaced lateral sacral fractures appear to be well-suited to percutaneous fixation techniques with cannulated screws placed under fluoroscopic guidance.

The anterior plating technique through a lower midline or Pfannenstiel's incision, as described by Hirvensalo et al. (Citation1993) and in more detail in this report, provides good extraperitoneal access to the inner surface of the pubic rami and to the anterior column of the acetabulum. Cole and Bolhofner (Citation1994) have used a limited Stoppa intrapelvic approach in the treatment of acetabular fractures, and later, Cole et al. (Citation1996) used it for treatment of pelvic fractures-as it provides a similar intrapelvic view. With the current technique, there was no need for dissection or separation of the inguinal neurovascular structures as is the case in the ilioinguinal approach (Letournel and Judet Citation1993). The anterior approach could be combined with the approach along the iliac crest, so that every anterior part of the pelvic ring and even the anterior side of the sacroiliac joint can be reached. We found this technically easier and less invasive for the patient. Protection of the external iliac vein as well as the obturator vessels and nerve is of major importance, however. This combined approach can be recommended for stabilization of simultaneous iliac fractures, sacroiliac dislocations or fracture dislocations and injuries to the anterior pelvic ring. Knowledge of the extraperitoneal intrapelvic region is mandatory.

The anterior pelvic ring was mainly stabilized with reconstruction plates with 3.5-mm screws. The fixation with plates can be considered accurate and reliable. Loss of reduction was seen in 1/75 patients who underwent anterior fixation with plates. Matta (Citation1996) also found in his series of 127 patients that the 72 fixations of the anterior pelvic ring were safe and reliable, and he recommended it for symphysis pubis dislocations, but only for the most severe pubic rami fractures. In our study in 2/16 patients, the position of the initially minimally displaced (< 10 mm) and unfixed fracture of the pubic rami worsened even though the posterior injury was adequately fixed. Anterior external fixator and intramedullary screw fixation of the rami in combination with the posterior fixation were used only in a few patients in our series. No definite conclusions could be made about these methods, but one loss of reduction was seen in the latter group.

Matta and Tornetta (Citation1996) reported excellent or good reduction results in 102 patients (95%) in a review of 107 patients with 38 Bucholz type II (type-B) injuries and 69 Bucholz type III (type- C) injuries. In their study, those patients who did not have their rami fractures fixed were excluded from the evaluation because there was generally 5- to 10-mm residual displacement of the fracture. They stated that this amount of displacement was considered clinically insignificant, but would artificially worsen the grading of the reduction. In our series, displacement was measured as the maximum distance between the fragments or separated portions in the posterior and anterior parts of the pelvis. Greater than 10 mm of displacement on the posterior or anterior part of the pelvic ring was considered unsatisfactory (fair or poor result). Despite these methodological differences, our radiographic results in this series were similar to those of the earlier study (Matta and Tornetta Citation1996).

The overall functional results were good or excellent in 83% of our patients, and were positively affected by stable anatomic or nearly anatomic reduction. Unsatisfactory reduction, failure of fixation and loss of reduction (maximal residual displacement > 5 mm) showed a statistically significant association with the unsatisfactory functional result. Malreduction or loss of reduction might be corrected in a reoperation even later than 6 weeks after the trauma. In all of our 5 reoperations, a clear radiological correction was achieved with a satisfactory functional result in 4 of them. There was also an association between permanent neurological injury and unsatisfactory functional outcome when single prognostic factors were analyzed. A relationship between unsatisfactory radiographic and functional results was first reported by Lindahl et al. (Citation1999) in an analysis of long-term outcome after definitive treatment of type-C injuries with an anterior external fixator. In 4 of our patients, the reason for an unsatisfactory functional result was unclear because all of these patients had a good reduction result and they did not have any neurological injuries. Lumbosacral plexus injuries were the main reason for an unsatisfactory functional result in patients with concomitant urological injuries.

Most of the patients in our series showed a clear recovery of the neurological deficiencies. Similar results were obtained by Reilly et al. (Citation1996) and Tornetta and Matta (Citation1996). Early reduction of the posterior pelvic ring seems to reduce the neurologic injury. It can be presumed that recovery of the lumbosacral nerves depends on the amount of initial damage to the nerve roots, and also on mechanical factors such as traction or compression of the neurologic structures by fragments of bone (Huittinen Citation1972, Denis et al. Citation1988). Reduction of the hemipelvis, prevention of traction of the injured neural structures by stabilizing the ring and decompression of the sacral nerve roots appears to be essential to the neurological recovery. This should be done urgently in the primary phase (within 1 or 2 days), whenever the neural injury is suspected and the patient has been stabilized hemodynamically.

Our findings suggest that there is a relationship between the radiographic and functional outcome. However, a permanent neurological injury may aggravate the functional outcome—even if the reduction of the pelvic ring fracture is anatomic. Unsatisfactory reduction, failure of fixation, loss of reduction and a permanent lumbosacral plexus injury were the most common reasons for an unsatisfactory functional result. Unstable pelvic ring injuries with progressive distraction or compression of the nerve roots with neurologic deficits are indications for operative treatment in the primary phase, once the patients have been stabilized hemodynamically. Special attention should be paid to preoperative planning and fixation of the most severe sacral fractures. The results of the current study favor reduction and internal fixation of symphyseal disruptions and displaced (> 10 mm) and unstable pubic rami fractures in conjunction with adequate posterior fixation, in order to achieve better stability for the whole pelvic ring.

No competing interests declared.

The authors thank Jarkko Pajarinen M.D. for statistical analysis.

- Bircher M D. Indications and techniques of external fixation of the injured pelvis. Injury 1996; 27(Suppl 2)S-B3–S-B19

- Burgess A R, Eastridge B J, Young J W. R, Ellison T S, Ellison P S, Jr, Poka A, Bathon G H, Brumback R J. Pelvic ring disruptions: Effective classification system and treatment protocols. J Trauma 1990; 30: 848–56

- Chapman M W, Olson S A. Open fractures, Fractures in adults. C A Rockwood, D P Green, R W Bucholz, J D Heckman. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia 1996; 4: 305–52

- Cole J D, Bolhofner B R. Acetabular fracture fixation via a modified Stoppa limited intrapelvic approach: Description of operative technique and preliminary treatment results. Clin Orthop 1994, 305: 112–23

- Cole J D, Blum D A, Ansel L J. Outcome after fixation of unstable posterior pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop 1996, 329: 160–79

- Denis F, Davis S, Comfort T. Sacral fractures: An important problem: Retrospective analysis of 236 cases. Clin Orthop 1988, 227: 67–81

- Ebraheim N A, Rusin J J, Coombs R J, Jackson W T, Holiday B. Percutaneous computer tomography-stabilization of pelvic fracture: Preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma 1987; 1: 197–204

- Evers B M, Cryer H M, Miller F B. Pelvic fracture hemorrhage. Priorities in management. Arch Surg 1989; 124: 422–4

- Gilliland M D, Ward R E, Barton R M, Miller P W, Duke J H. Factors affecting mortality in pelvic fractures. J Trauma 1982; 22: 691–3

- Goldstein A, Phillips T, Sclafani S J. A, Scalea T, Duncan A, Goldstein J, Panetta T, Shafton G. Early open reduction and internal fixation of the disrupted pelvic ring. J Trauma 1986; 26: 325–33

- Greenspan L, McLellan B A, Greig H. Abbreviated injury scale and injury severity score: A scoring chart. J Trauma 1985; 25: 60–4

- Gunterberg B, Goldie I, Slätis P. Fixation of pelvic fractures and dislocations. An experimental study on the loading of pelvic fractures and sacro-iliac dislocations after external compression fixation. Acta Orthop Scand 1978; 49: 278–86

- Gylling S F, Ward R E, Holcroft J W, Bray T J, Chapman M W. Immediate external fixation of unstable pelvic fractures. Am J Surg 1985; 150: 721–4

- Helfet D L, Schmeling G J. Complications, Fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum. M Tile. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore 1995; 2: 451–67

- Hirvensalo E, Lindahl J, Böstman O. A new approach to the internal fixation of unstable pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop 1993, 297: 28–32

- Huittinen V M. Lumbosacral nerve injury in fracture of the pelvis. A postmortem radiographic and patho-anatomical study. Acta Chir Scand 1972; 429(Suppl)1–43

- Kellam J F. The role of external fixation in pelvic disruptions. Clin Orthop 1989, 241: 66–82

- Kellam J F, McMurtry R Y, Paley D, Tile M. The unstable pelvic fracture: Operative treatment. Orthop Clin North Am 1987; 18: 25–41

- Lansinger O, Karlsson J, Berg U, Måre K. Unstable fractures of the pelvis treated with a trapezoid compression frame. Acta Orthop Scand 1984; 55: 325–9

- Leighton R K, Waddell J P, Bray T J, Chapman M W, Simpson L, Martom R B, Sharkey N A. Biomechanical testing of new and old fixation devices for vertical shear fractures of the pelvis. J Orthop Trauma 1991; 5: 313–7

- Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the acetabulum. 2. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1993

- Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E, Böstman O, Santavirta S. Failure of reduction with an external fixator in the treatment of injuries of the pelvic ring: Long-term evaluation of 110 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81: 955–62

- Majeed S A. Grading the outcome of pelvic fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1989; 71: 304–6

- Matta J M. Indications for anterior fixation of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop 1996, 329: 88–96

- Matta J M, Saucedo T. Internal fixation of pelvic ring fractures. Clin Orthop 1989, 242: 83–97

- Matta J M, Tornetta III P. Internal fixation of unstable pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop 1996, 329: 129–40

- McLaren A C, Rorabeck C H, Halpenny J. Long-term pain and disability in relation to residual deformity after displaced pelvic ring fractures. Can J Surg 1990; 33: 492–4

- Mears D C, Fu F. External fixation in pelvic fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 1980; 11: 465–79

- Mucha P, Welch T J. Hemorrhage in major pelvic fractures. Surg Clin North Am 1988; 68: 757–73

- Pohlemann T, Bosch U, Gänsslen A, Tscherne H. The Hannover experience in management of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop 1994, 305: 69–80

- Pohlemann T, Gänsslen A, Schellwald O, Culemann U, Tscherne H. Outcome after pelvic ring injuries. Injury 1996; 27(Suppl 2)S-B31–S-B38

- Reilly M C, Zinar D M, Matta J M. Neurologic injuries in pelvic ring fractures. Clin Orthop 1996, 329: 28–36

- Rothenberger D A, Fischer R P, Strate R G, Velasco R, Perry J F, Jr. The mortality associated with pelvic fractures. Surgery 1978; 84: 356–61

- Routt M L. C, Simonian P T. Closed reduction and percutaneous skeletal fixation of sacral fractures. Clin Orthop 1996a, 329: 121–8

- Routt M L, Simonian P T. Internal fixation of pelvic ring disruptions. Injury 1996b; 27(Suppl 2)S-B20–S-B30

- Routt M L. C, Simonian P T, Grujic L. The retrograde medullary superior pubic ramus screw for the treatment of anterior pelvic disruptions: A new technique. J Orthop Trauma 1995; 9: 35–44

- Slätis P, Karaharju E. External fixation of the pelvic girdle with a trapezoid compression frame. Injury 1975; 7: 53– 6

- Slätis P, Karaharju E. External fixation of unstable pelvic fractures: Experiences in 22 patients treated with a trapezoid compression frame. Clin Orthop 1980, 151: 73–80

- Tile M. Pelvic ring fractures: Should they be fixed?. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1988; 70: 1–12

- Tile M. Fractures of the pelvis and acetabulum. 2. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore 1995

- Tile M. The management of unstable injuries of the pelvic ring (Editorial). J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81: 941–3

- Tornetta III P, Matta J M. Outcome of operatively treated unstable posterior pelvic ring disruptions. Clin Orthop 1996, 329: 186–93

- Tscherne H, Regel G. Care of the polytraumatised patient. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78: 840–52

- Ward E F, Tomasin J, Vander Griend R A. Open reduction and internal fixation of vertical shear pelvic fractures. J Trauma 1987; 27: 291–5

- Wild J J, Hanson G W, Tullos H S. Unstable fractures of the pelvis treated by external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1982; 64: 1010–20

- Wolinsky P R. Assessment and management of pelvic fracture in the hemodynamically unstable patient. Orthop Clin North Am 1997; 28: 321–9