Abstract

Background Desmoid tumors have a tendency to recur locally, and traditionally they have been treated surgically. No treatment is sometimes indicated, however; this requires a morphological diagnosis that is not based on a surgical specimen. In this study we aimed to identify the diagnostic accuracy of needle and core biopsy for the morphological diagnosis of desmoid.

Methods We compared the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy (CNB) in 69 and 26 patients, respectively, who had had surgical resections for desmoid. We also reviewed 15 additional cases that had been incorrectly diagnosed as desmoid on FNA but which had different diagnoses after surgery.

Results FNA-based diagnoses of desmoid/fibromatosis were rendered in 35 of 69 cases, and other benign spindle cell proliferations in 26 cases and spindle cell sarcoma in the remaining 4 cases. All 26 CNBs were either suggested to correspond to desmoid (24) or other benign spindle cell lesions (2). Of the 15 FNAs incorrectly diagnosed as desmoid, 2 were found to be sarcomas.

Interpretation FNA is fairly reliable for recognition of the benign nature of desmoids. Occasional over- and under-diagnosis of malignancy can occur, however. CNB appears to be more reliable.

Desmoid tumors are rare and benign—but frequently locally aggressive—lesions originating in musculoaponeurotic tissues (Reitamo Citation1983, Markhede et al. Citation1986). The tumors are often classified into 2 groups, abdominal and extra-abdominal, but the histological appearance is identical.

The preoperative diagnosis is usually based on clinical findings, imaging studies and morphological analysis, including open surgical biopsies, core needle biopsies (CNBs) or fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. There have been only a few published studies of single cases or relatively small series of desmoids examined by FNA, with some indicating its usefulness (Raab et al. Citation1993, Åkerman Citation2003) and others pointing out the pitfalls of occasional misinterpretation of malignancies (Powers et al. Citation1994, Dey et al. Citation2004). The few reports of core needle biopsies in the preoperative diagnosis of desmoids suggest that it is a very useful technique (Serpell and Pitcher Citation1998, Ray-Coquard et al. Citation2003). Recently, there have been suggestions that one should refrain from treatment of many cases of desmoid tumors, with surgical resection being limited to patients with significant symptoms or problematic, potentially life-threatening complications due to the location of the tumor (Dalén et al. Citation2003, Citation2006). A correct diagnosis is mandatory in those patients with desmoid who are to be followed rather than to be treated by surgical resection.

We compared the accuracy and potential pitfalls of FNA with those of CNB in the preoperative diagnosis of desmoid tumors.

Material and methods

In order to evaluate the accuracy and pitfalls of FNA and CNB in the diagnosis of desmoids, we studied three groups of patients: (1) All cases from Sahlgrenska University Hospital diagnosed from 1969 through 2001 with a definitive diagnosis of desmoid based on surgical resection, and with corresponding preoperative FNA, were identified by analyzing both the database at the Department of Pathology and the files of the Department of Orthopaedics. This corresponded to 69 patients. The FNA smears and subsequent surgical specimens were reviewed, as well as cytology and pathology reports; (2) All cases from Sahlgrenska University Hospital diagnosed from 1984 through 2002 in which the preoperative FNA diagnosis suggested desmoid fibromatosis but with a divergent histological diagnosis on the surgical resection were also retrieved, and 15 patients were identified; (3) All cases with a final diagnosis of desmoid fibromatosis who had had a CNB in the pretreatment investigation were identified from the files of the Departments of Orthopaedics, and Cytology and Pathology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital (1999–2004), corresponding to 13 patients. 13 additional core needle biopsies of desmoids were identified from the files of the Department of Musculoskeletal Pathology, the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust at the University of Birmingham (2004–2005). In 5 of the Sahlgrenska cases, FNA had also been performed. The data from these 5 cases are included with the 69 FNA cases.

FNA techniques

All aspirations were performed by the cytologist who issued the reports with appropriate clinical presentation and radiographic information. The needles used had a diameter of 0.7–0.8 mm (gauge 22–21). Disposable plastic syringes were used together with a special holder. The cell material obtained was smeared on glass slides, air dried, and then stained according to the May-Grünewald-Giemsa method.

Core needle biopsy

The CNBs were all performed by experienced orthopedic surgeons or radiologists using a biopsy instrument (Bard Magnum) and a core tissue biopsy needle with a diameter of 12- or 14-gauge. The tissue samples collected were up to 2.5 cm in length.

Results

Desmoid tumors for which FNA had been used in the preoperative diagnosis (69 patients)

A correct preoperative diagnosis of desmoid tumor or fibromatosis had been made in 35 of the 69 cases identified (). Desmoid tumor or fibromatosis had been suspected in 4 additional cases, with nodular fasciitis being in the differential diagnosis. Diagnosis of a benign spindle cell fibroblastic proliferation of undetermined type had been made in 16/69 cases. Other benign FNA diagnoses included schwannoma (1 case) and nodular fasciitis (5 cases). A diagnosis of spindle cell sarcoma was made in 4 cases, one of which was suggested to be low grade. In 4 cases, the FNA material was too scant to render any diagnosis.

Table 1. 69 desmoid tumors with FNA used in the preoperative diagnosis

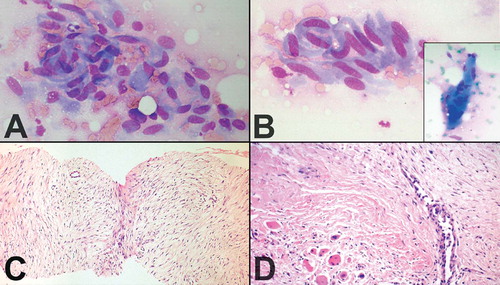

The FNA smears of desmoids had a fairly uniform appearance, differing from case to case mainly by a highly variable yield, with some smears having very scant material and others being strikingly cellular. The tumor cells had the characteristic features of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic cells, being spindle-shaped or polygonal and in most cases with fairly abundant basophilic cytoplasm. Poorly preserved spindle cells with stripped, “naked” oval nuclei were also seen in several cases. The oval nuclei had finely dispersed chromatin with no or few small nucleoli. Tumor cells occurred as single cells but they were often in coherent clusters, forming a vague fascicular pattern ( and ). In addition to clusters of tumor cells, there were also fragments of a collagenized, finely fibrillar background matrix. In many cases, a striking feature was the occurrence of large, multinucleate cells representing atrophic muscle fibers (, insert).

A and B: Fine-needle aspirates of desmoid tumors showing coherent clusters of uniform spindle cells with abundant cytoplasm and oval-to-elongated nuclei with evenly distributed chromatin. Large, basophilic multinucleate cells representing atrophic muscle fibers were frequently seen (panel B, insert). May-Grünewald Giemsa stain. C and D: Core needle biopsies of desmoid tumors showing the characteristic histological features, including evenly distributed fibroblastic tumor cells enclosed in a collagenous matrix, medium-sized angulated vessels and enclosure of atrophic muscle fibers (panel D, bottom left).

Cases with an FNA-based diagnosis of desmoid and a divergent final diagnosis (15 patients)

The final diagnoses based on examination of the surgical specimens were other types of benign mesenchymal lesions in 12/15 cases, sarcomas in 2 cases (1 low-grade fibrosarcoma and 1 monophasic fibrous synovial sarcoma), and hemangiopericytoma of uncertain malignant potential in one case ().

Table 2. Desmoid diagnosis suggested by FNA with other final postoperative diagnosis

Desmoids diagnosed by core needle biopsy (26 patients)

A definitive diagnosis of desmoid/fibromatosis was made in 24/26 cases (). A differential diagnosis of fibromatosis and reactive scar or cellular intramuscular myxoma was suggested in 1 case each. There was no suggestion of malignancy in any of the cases. In 1 additional case (a young woman), the core needle biopsy was believed to represent a desmoid of the abdominal wall; this was partially due to erroneous clinical information indicating that the tumor involved the abdominal wall. The biopsy was, in fact, from an intrauterine cellular leiomyoma.

Table 3. Desmoids diagnosed by core needle biopsy

Of the 26 core needle biopsies (1–5 cores) measuring 5–25 mm in length, all but 2 had features characteristic of desmoid tumor, including a moderately cellular collagen-producing fascicular spindle cell proliferation of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic cells without cytologic atypia (). The thin-walled ectatic vessels typical of desmoid were often identified. The infiltrative growth in skeletal muscle () and fascia could often be seen. 2 cases had a somewhat different appearance to that of a classical desmoid. One of these had a prominent myxoid matrix, suggesting the possibility of a cellular intramuscular myxoma, while the other one had a more fibrous appearance as can be seen in a scar or cicatrix.

Discussion

For several decades, FNA has been the most widely used preoperative morphological technique at several orthopedic tumor centers in Scandinavia, particularly in Sweden. Its usefulness in the diagnosis of soft tissue lesions has been shown in a number of studies (Åkerman et al. Citation1980, Walaas and Kindblom Citation1985, Willen et al. Citation1995, Åkerman Citation1997, Iwamoto Citation1999).

There have been very few reports in the literature on the application of FNA in the preoperative diagnosis of desmoids (Raab et al. Citation1993, Powers et al. Citation1994, Åkerman Citation2003, Dey et al. Citation2004). Our review of 69 fine-needle aspirates of desmoids clearly shows its usefulness. The fine-needle aspirates from the 4 desmoids that had been misinterpreted as spindle cell sarcomas were all unusually cellular, with a more variable morphology than is usual for fibromatosis. All 4 patients had their tumors surgically removed, 2 with wide margins (chest wall and thigh), 1 with a marginal margin (neck) and 1 with an intralesional margin (ankle). The patient with an intralesional margin and the one with wide margins developed local recurrences. 1 patient underwent radiotherapy after a recurrence and the other patient had radiotherapy after surgery of a local recurrence. 1 patient is alive and disease-free (3 years later), 2 are alive with disease (1.5 and 17 years later) and 1 died from another cause (23 years later). The misinterpretation of the FNA results as sarcomas in these 4 cases does not seem to have changed the surgical treatment significantly, or led to any complications.

Occasional problems in the FNA-based recognition of desmoids are further illustrated by the series of 15 cases in which the cytological findings were believed to represent desmoid but turned out to be other types of mesenchymal lesions. However, most of these misdiagnoses were other types of benign lesions (13/15); they turned out to be malignancies in only 2 cases. The benign group included cases of nodular fasciitis, schwannoma, scar and fibroma of tendon sheath; all of these have morphological features in common with desmoid. The other benign lesions, such as lipomas, granular cell tumor, elastofibroma, hemangioma and hemangiopericytoma, were not recognized—mainly because the aspirate was paucicellular or unrepresentative. The 2 sarcomas that had been misdiagnosed as desmoids were low-grade fibrosarcoma and monophasic synovial sarcoma, respectively. In the former case, the fine-needle aspirate was paucicellular and consisted of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic cells with minimal atypia. In the latter case, the aspirate was composed of monotonous spindle cells with scant cytoplasm and uniform oval nuclei with an even distribution of chromatin (Åkerman et al. Citation2003). These 2 patients had slowly growing tumors in the chest wall and shoulder. The clinical impression of the chest wall mass was desmoid. The chest wall tumor that was a fibrosarcoma was removed with an intralesional margin and required a wide reresection. There was no evidence of disease 1 year after diagnosis. The patient with a shoulder tumor (synovial sarcoma) had a preoperative incisional biopsy (since the surgeon apparently doubted the FNA-based diagnosis) and this established the correct diagnosis. The tumor in this case was removed with a marginal margin. The patient received both postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy. He developed lung metastases which were removed 3 years after the primary operation. At 5 years follow-up (2 years after metastasectomy) he had no evidence of disease.

The occasional over-diagnosis of sarcoma in desmoid tumors using FNA and the under-recognition of sarcomas falsely diagnosed as desmoids on FNA have been reported previously (Åkerman et al. Citation1980, Citation1985). Similarly to the results of our series, the clinical consequences of these misdiagnoses were minor with the exception of 1 patient.

The core needle biopsies in our series always produced adequate and representative material that led to the correct diagnosis of desmoid in 24/26 cases and desmoid as the most likely diagnosis in the 2 remaining cases. The major advantage of core needle biopsies over FNA is that the architecture of the lesion—including the ectatic, thin-walled vascular channels that are so characteristic of desmoid—is preserved.

The simplicity of the core needle biopsy technique, the almost constant representative material obtained in the hands of surgeons or others with extensive experience, the abundance of material obtained that allows recognition of the histological characteristics and growth pattern, and the high degree of diagnostic accuracy all suggest that this technique is the diagnostic method of choice. In our opinion, FNA still has a role to play in the diagnosis of desmoids, particularly in cases with tumors located at sites that are in close proximity to major vessels or nerves, pleura and lungs, which would lead to unnecessary risks or complications when a core needle biopsy is used. However, there were no complications from the core biopsies in our series.

This work was financially supported by the Johan Jansson Foundation for Cancer Research and by grants from the Swedish government under the LUA/ALF agreement.

No competing interests declared.

Contributions of authors

MD sampled files, reviewed clinical data and histopathology slides, and performed clinical examination of patients. He also produced an outline of the manuscript. JMMK and LGK contributed ideas and produced an outline of the study design. They also reviewed all cytology and histopathology slides and prepared the final manuscript in collaboration with the other authors. WR reviewed cytology and histopathology slides. VPS prepared and reviewed cytology and histopathology slides.

- Åkerman M. The cytology of soft tissue tumours. Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl 273) 1997; 273: 54–9

- Åkerman M. Benign and malignant soft tissue tumors. Diagnostic cytopathology, W Grey, G McKee. Churchill Livingstone, London 2003; 896–7

- Åkerman M, Idvall I, Rydholm A. Cytodiagnosis of soft tissue tumors and tumor-like conditions by means of fine needle aspiration biopsy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1980; 96: 61–7

- Åkerman M, Rydholm A, Persson B M. Aspiration cytology of soft-tissue tumors. The 10-year experience at an orthopedic oncology center. Acta Orthop Scand 1985; 56: 407–12

- Åkerman M, Ryd W, Skytting B. Fine-needle aspiration of synovial sarcoma: criteria for diagnosis: retrospective reexamination of 37 cases, including ancillary diagnostics. A Scandinavian Sarcoma Group study. Diagn Cytopathol 2003; 28: 232–8

- Dalén B P M, Bergh P M, Gunterberg B U. Desmoid tumors: a clinical review of 30 patients with more than 20 years' follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74: 455–9

- Dalén B P M, Geijer M, Kvist H, Bergh P M, Gunterberg B U P. Clinical and imaging observations of desmoid tumors left without treatment. Acta Orthopedica 2006; 77: 932–7

- Dey P, Mallik M K, Gupta S K, Vasishta R K. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumours and tumour-like lesions. Cytopathology 2004; 15: 32–7

- Iwamoto Y. Diagnosis and treatment of soft tissue tumors. J Orthop Sci 1999; 4: 54–65

- Markhede G, Lundgren L, Bjurstam N, Berlin O, Stener B. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors. Acta Orthop Scand 1986; 57: 1–7

- Powers C N, Berardo M D, Frable W J. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol 1994; 10: 232–40, discussion 241

- Raab S S, Silverman J F, McLeod D L, Benning T L, Geisinger K R. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of fibromatoses. Acta Cytol 1993; 37: 323–8

- Ray-Coquard I, Ranchere-Vince D, Thiesse P, Ghesquieres H, Biron P, Sunyach M P, Rivoire M, Lancry L, Meeus P, Sebban C, Blay J Y. Evaluation of core needle biopsy as a substitute to open biopsy in the diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39: 2021–5

- Reitamo J J. The desmoid tumor. IV. Choice of treatment, results, and complications. Arch Surg 1983; 118: 1318–22

- Serpell J W, Pitcher M E. Pre-operative core biopsy of soft-tissue tumours facilitates their surgical management. Aust N Z J Surg 1998; 68: 345–9

- Walaas L, Kindblom L G. Lipomatous tumors: a correlative cytologic and histologic study of 27 tumors examined by fine needle aspiration cytology. Hum Pathol 1985; 16: 6–18

- Willen H, Akerman M, Carlen B. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumours; a review of 22 years experience. Cytopathology 1995; 6: 236–47