Abstract

Background and purpose — Heavily displaced radial neck fractures in children are sometimes associated with poor outcome. A substantial number of these fractures require open reduction. We hypothesized that Judet type-IV fractures with a completely displaced radial head would result in a worse outcome than radial neck fractures with remaining bony contact.

Patients and methods — We analyzed 19 children (median age 9.7 (4–13) years) who were treated for Judet type-IV radial neck fractures between 2001 and 2014. The outcome was assessed at the latest outpatient visit using the Linscheid-Wheeler score at a median time of 3.5 (1–8) years after injury. The patients were assigned either to group A (9 fractures with remaining bony contact between the radial head and the radial neck) or to group B (10 fractures without any bony contact).

Results — The 2 groups were similar concerning age and sex. The rate of additional injuries was higher in group B (7/10 vs. 1/9 in group A; p = 0.009). The rate of open reduction was higher in group B (5/10 vs. 0/9 in group A; p = 0.01). Poor outcome was more common in group B (4/10 vs. 0/9 in group A; p = 0.03). In group B, the proportion of children with poor outcome (almost half) was the same irrespective of whether open or closed reduction had been done.

Interpretation — The main causes of unfavorable results of radial neck fracture in children appear to be related to the energy of the injury and the amount of displacement—and not to whether open reduction was used.

Radial neck fractures account for slightly more than 1% of all fractures in children (Fuentes-Salguero et al. Citation2012) and they represent about 5–10% of elbow injuries (Novoth Citation2002). The most common injury mechanism is a fall on the outstretched arm combined with a valgus stress of the elbow (Eberl et al. Citation2010).

The Judet classification identifies 4 types of fracture, depending on the displacement of the radial head. Type I is a non-displaced fracture, type II involves angulation of less than 30°, and type III involves angulation of between 30° and 60°. Type-IV fractures are those with more than 60° of angulation of the radial head (Eilert and Erickson Citation2006).

Most radial neck fractures are minimally displaced or non-displaced, and they are treated non-operatively with cast immobilization (Okcu and Aktuglu Citation2007). However, there is broad consensus that both Judet type-III and type-IV fractures necessitate operative reduction and stabilization (Eberl et al. Citation2010). Several options—ranging from percutaneous pin reduction, elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN), to open reduction with or without internal fixation—have been described (Falciglia et al. Citation2014).

Complications following displaced fractures of the radial neck are common and include limited range of motion, premature physeal closure, cubitus valgus, and overgrowth of the radial head (Novoth Citation2002, Eberl et al. Citation2010). The most devastating sequela is avascular necrosis of the radial head due to disruption of the blood supply, which can be damaged either by the injury itself or by surgical manipulation when open reduction is indicated (Stiefel et al. Citation2001, Eberl et al. Citation2010). Higher rates of avascular necrosis have been reported after open rather than closed reduction (Ursei et al. Citation2006). Moreover, worse outcome has been reported for Judet-IV fractures than for Judet-III fractures (Novoth Citation2002). Even so, it is still unclear whether or not completely displaced radial neck fractures without any bony contact have a different outcome and a higher rate of complications than fractures with bony contact. These 2 fracture types are not differentiated from each other in the Judet classification.

We therefore compared the outcome of Judet-IV radial neck fractures with bony contact () to the outcome of such fractures without any bony contact () in a consecutive series of children. We hypothesized that Judet type-IV fractures with a completely displaced radial head would result in a worse outcome than radial neck fractures with some remaining bony contact.

Figure 1. A 9-year-old boy sustained a radial neck fracture (Judet type-IV) with remaining bony contact of the radial neck, after falling on a level surface (panels a and b). Panels c and d show radiographs 16 days after elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN). After implant removal 3 months postoperatively, there was correct positioning of the radial head and neck (panels e and f). At clinical follow-up 2.3 years after the initial trauma, the patient was free of symptoms and had full range of motion.

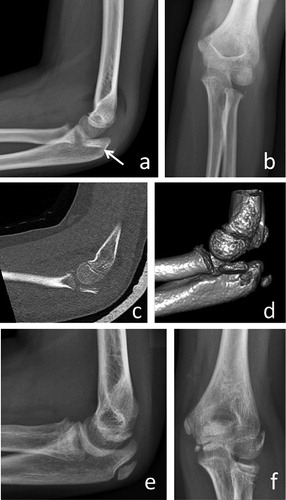

Figure 2. A 7-year-old girl had a type-B lesion after falling on a level surface (panels a and b). Note the hardly visible radial head on conventional radiographs (arrow). A CT scan (panels c and d) revealed the location of the radial head. Open reduction and elastic stable intramedullary nailing (ESIN) was necessary. 19 months later, there were signs of shortening and angulation but no evidence of avascular necrosis (panels e and f). Clinically, the patient was free of symptoms, with full range of motion and a Linscheid-Wheeler score of I.

Patients and methods

By using our hospital’s trauma database, we identified children and adolescents (up to the age of 18 years) who were treated for radial neck fractures between 2001 and 2014. Inclusion criteria were a radiographically confirmed Judet-IV radial neck fracture; complete clinical data including age, affected side, sex, trauma mechanism, additional injuries, type of treatment; and a follow-up of more than 1 year.

During the study period of 14 years, 19 children (11 of them boys) with a median age of 9.7 (4–13) years were treated for Judet-IV radial neck fractures. All the patients had open radial neck physes at the time of injury.

The outcome was assessed at the latest outpatient visit using the Linscheid-Wheeler score (Linscheid and Wheeler Citation1965). This score grades the results as excellent, good, fair, and poor. An excellent result is defined as a full range of motion and normal elbow function in all respects. A good result is achieved when the loss of flexion and extension is less than 15° without any remaining pain and/or instability. Fair results are characterized by less than 30° loss of flexion, extension, pronation, or supination and only mild complaints of instability or pain on heavy use. A poor outcome is characterized by more than 30° loss of motion and residual pain, instability, or residual neurovascular disability.

To compare fractures with and without bony contact, patients were assigned to 2 groups. Group A included the 9 Judet-IV fractures with remaining bony contact of the radial head to the radial neck. The 10 Judet-IV fractures without such bony contact were assigned to group B.

Statistics

SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. Data are expressed as median and range. The Mann-Whitney U-test was chosen for comparison of the patient ages in groups A and B. For comparisons of gender distribution, associated injuries, and outcome, the chi-squared test was used. Significant differences were assumed for p-values less than 0.05.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Graz (entry no. 27-371 ex 14/15).

Results

In 9 patients, the radial neck still had some bony contact with the radius (group A). The remaining 10 children had a completely displaced radial head without bony contact (group B). The 2 groups had similar age and sex distribution. However, the rate of additional injuries was higher in group B (p = 0.009) (). The main mechanism of injury in group A was a fall on a level surface. The fractures of the children in group B were mainly caused by falls from a height of less than 2 meters, or sports injuries.

Table 1. Comparison of age, gender distribution, and additional injuries in group A (bony contact) and group B (no bony contact)

All 9 fractures in group A were treated with closed reduction and ESIN. Open reduction was done in 5 children in group B, whereas 5 fractures were treated with closed reduction. All fractures in group B were stabilized by ESIN.

In 2 children in group B, a reoperation became necessary. In 1 child, an exostosis was removed 6 months after the initial surgical procedure. In the second child, aged 13 years, the postoperative course was complicated by the development of an avascular necrosis of the radial head following open reduction and ESIN. The patient complained of increasing pain and developed loss of motion combined with increasing density of the radial head on radiographs (as a sign of necrosis). The patient opted for a definitive treatment as soon as possible. We resected the radial head 5 months after injury. At follow-up of 2.4 years, the patient showed improved range of motion and had occasional pain, but no signs of elbow instability or neurovascular disabilities. The outcome was classified as Linscheid-Wheeler IV.

The outcome was assessed at a median length of time of 42 (14–99) months after injury (). According to the Linscheid and Wheeler score, the outcome was excellent in 12 children, good in 3, and poor in 4. The proportion of fractures leading to a poor outcome was higher in group B. Excellent outcome was more common in group A (p = 0.02). The rates of poor outcome after closed reduction and open reduction were similar ().

Table 2. Demographic data, gender distribution, fracture type, treatment, Linscheid and Wheeler score, and length of follow-up

Table 3. Outcome in 19 children with radial neck fractures

Discussion

We assessed the outcome of Judet type-IV radial neck fractures separately for fractures with and without bony contact. The main findings were that the proportion of fractures necessitating open reduction was higher in patients who had completely displaced fractures without bony contact. However, the necessity of open reduction did not influence the rate of poor outcome.

Tan and Mahadev (Citation2011) reported that only 7 of 108 children with radial neck fractures sustained a Judet type-IV fracture. Most studies analyzing outcome have included patients with radial neck fractures of all severities (Tan and Mahadev Citation2011). However, Stiefel et al. (Citation2001) reported the outcome of 6 Judet type-IV fractures. We were able to include 19 patients with Judet type-IV fractures, representing one of the largest cohorts of such patients.

The main mechanism of injury causing radial neck fractures is a fall on the outstretched hand. In an extended elbow, the capitulum of the humerus exerts a strong force to the proximal radius, which may result in a fracture with displacement of the radial head (Eberl et al. Citation2010). The resulting valgus stress may lead to additional injuries such as avulsion fractures of the ulnar epicondyle, rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament, or fractures of the olecranon or proximal ulna (Jeffery Citation1950). The frequency of such associated injuries varies between 15% and 60% (Al-Aubaidi et al. Citation2012, Falciglia et al. Citation2014). The high rate of additional injuries in almost half of the children in our study population may be explained by the fact that we only included the most severe forms of radial neck fractures associated with higher-energy trauma.

While excellent outcome has been reported for lower-grade radial neck fractures (Al-Aubaidi et al. Citation2012, Eberl et al. Citation2010), higher-grade fractures are associated with worse outcome (Gutierrez-de la Iglesia et al. Citation2015). The vulnerable vascular supply of the radial head is mainly responsible for worse outcome—including avascular necrosis, growth arrest with cubitus valgus, and restricted range of motion (Eberl et al. Citation2010, Tan and Mahadev Citation2011). However, the relative contribution of the injury per se or the surgical manipulation is debated. Many authors have stated that the risk of complications is higher in fractures treated with open reduction. For instance, De Mattos et al. (Citation2016) reported on 193 consecutive children with radial neck fractures, 13% of whom required operative treatment. The authors could show that open reduction increased the risk of fair and poor outcome and that final outcomes were not related to preoperative displacement and the presence of associated injures. This contrasts with our findings showing a worse outcome in fractures without bony contact between the radial neck and the radius—and comparable outcomes for these fractures following either open or closed reduction. Our results are in accordance with another study showing no statistically significant correlation between type of surgery and final outcome, as assessed by the Mayo elbow performance score in a group of 51 children with Judet type-III and type-IV fractures (Gutierrez-de la Iglesia et al. Citation2015). Moreover, the final functional outcome was associated with the initial Judet grade.

In summary, our findings support the assumption that a disruption of the vascular supply due to the initial injury—and not the surgical manipulation of the radial head—may be the main cause of unfavorable outcome. As a consequence, we believe that in cases of unsuccessful or suboptimal closed reduction, open reduction should be performed because avascular necrosis is not inevitable, even in cases with a completely displaced radial head ().

MK analyzed the data and wrote parts of the manuscript. RE initiated the study and wrote parts of the manuscript. CC collected the data and wrote parts of the manuscript. TK collected the data and performed the statistics. HT critically reviewed the manuscript. GS wrote parts of the manuscript.

- Al-Aubaidi Z, Pedersen N W, Nielsen K D. Radial neck fractures in children treated with the centromedullary Metaizeau technique. Injury 2012; 43 (3): 301–5.

- De Mattos C B, Ramski D E, Kushare I V, Angsanuntsukh C, Flynn J M. Radial neck fractures in children and adolescents: An examination of operative and nonoperative oreatment and Outcomes. J Pediatr Orthop 2016; 36(1): 6–12

- Eberl R, Singer G, Fruhmann J, Saxena A, Hoellwarth M E. Intramedullary nailing for the treatment of dislocated pediatric radial neck fractures. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2010; 20 (4): 250–2.

- Eilert R E, Erickson M A. Fracture s of the proximal radius and ulna. In: Fractures in children (Ed. Beaty JH, Kasser J R). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia 2006; 11: 444–90.

- Falciglia F, Giordano M, Aulisa A G, Di Lazzaro A, Guzzanti V. Radial neck fractures in children: results when open reduction is indicated. J Pediatr Orthop 2014; 34 (8): 756–62.

- Fuentes-Salguero L, Downey-Carmona F J, Tatay-Diaz A, Moreno-Dominguez R, Farrington-Rueda D M, Macias-Moreno M E, Quintana-del Olmo J J. [Radial head and neck fractures in children]. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 2012; 56 (4): 300–5.

- Gutierrez-de la Iglesia D, Perez-Lopez L M, Cabrera-Gonzalez M, Knorr-Gimenez J. Surgical techniques for displaced radial neck fractures: Predictive factors of functional results. J Pediatr Orthop 2015; [Epub ahead of print]

- Jeffery C C. Fractures of the head of the radius in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1950; 32-B (3): 314–24.

- Linscheid R L, Wheeler D K. Elbow dislocations. JAMA 1965; 194 (11): 1171–6.

- Novoth B. Closed reduction and intramedullary pinning of radial neck fractures in children. Orthopaedics and trauma 2002; 313–322.

- Okcu G, Aktuglu K. Surgical treatment of displaced radial neck fractures in children with Metaizeau technique. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2007; 13 (2): 122–7.

- Stiefel D, Meuli M, Altermatt S. Fractures of the neck of the radius in children. Early experience with intramedullary pinning. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83 (4): 536–41.

- Tan B H, Mahadev A. Radial neck fractures in children. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011; 19 (2): 209–12.

- Ursei M, Sales de Gauzy J, Knorr J, Abid A, Darodes P, Cahuzac J P. Surgical treatment of radial neck fractures in children by intramedullary pinning. Acta Orthop Belg 2006; 72 (2): 131–7.