Abstract

Background and purpose — Patients with osteoporosis who present with an acute onset of back pain often have multiple fractures on plain radiographs. Differentiation of an acute osteoporotic vertebral fracture (AOVF) from previous fractures is difficult. The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of concomitant AOVFs and previous OVFs in patients with symptomatic AOVFs, and to identify risk factors for concomitant AOVFs.

Patients and methods — This was a prospective epidemiological study based on the Registry of Pathological Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures (REPAPORA) with 1,005 patients and 2,874 osteoporotic vertebral fractures, which has been running since February 1, 2006. Concomitant fractures are defined as at least 2 acute short-tau inversion recovery (STIR-) positive vertebral fractures that happen concomitantly. A previous fracture is a STIR-negative fracture at the time of initial diagnostics. Logistic regression was used to examine the influence of various variables on the incidence of concomitant fractures.

Results — More than 99% of osteoporotic vertebral fractures occurred in the thoracic and lumbar spine. The incidence of concomitant fractures at the time of first patient contact was 26% and that of previous fractures was 60%. The odds ratio (OR) for concomitant fractures decreased with a higher number of previous fractures (OR =0.86; p = 0.03) and higher dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry T-score (OR =0.72; p = 0.003).

Interpretation — Concomitant and previous osteoporotic vertebral fractures are common. Risk factors for concomitant fractures are a low T-score and a low number of previous vertebral fractures in cases of osteoporotic vertebral fracture. An MRI scan of the the complete thoracic and lumbar spine with STIR sequence reduces the risk of under-diagnosis and under-treatment.

The main symptom of acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures (AOVFs) with or without trauma is a new onset of back pain. Plain radiography and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thoracic and/or lumbar spine are often performed. Patients with osteoporosis often show multiple fractures distributed over the whole spine. Differentiation of single acute and concomitant AOVFs from previous fractures is difficult, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most adequate image modality for this question. MRI may also reveal occult AOVFs (Park et al. Citation2013, Biber et al. Citation2016). The resources for using MRI are limited. In addition, it is still unclear whether using MRI of the spine in patients with AOVF can improve clinical outcome through higher diagnostic accuracy. The distribution of AOVFs is not well investigated, and a better understanding of the location of concomitant and previous fractures may lead to adapted and improved imaging standards.

Considering that most osteoporotic spine fractures are asymptomatic, it is difficult to identify the symptomatic fractures, especially in patients with concomitant fractures.

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of concomitant AOVFs and previous OVFs in patients with symptomatic AOVFs, and to identify risk factors for concomitant AOVFs.

Patients and methods

651 women and 254 men with 1,388 AOVFs and 1,486 previous vertebral fractures (in total, 2,874 OVFs) were enrolled in this clinical study. The prospective data acquisition was solely based on data from the hospital data information system. The data were collected from the Registry of Pathological Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures (REPAPORA), which serves healthcare research. The REPAPORA was established on February 1, 2006. Every patient signs an informed consent document on admission to hospital, regarding the use of the routine clinical data that are acquired during standard procedures, diagnostics, and therapeutic measures. All the data included were derived from patients’ primary consultations at our hospital.

No intervention, diagnostic procedure, or therapeutic procedure was performed for study purposes. There are no scheduled follow-up visits. The results of REPAPORA data acquisition and evaluation are re-examined regularly, and they have influenced standard operating procedures such as routine recommendation of bone density measurements in 2008, in-hospital/departmental establishment of the use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for every patient with osteoporotic fractures in 2010, establishment of a patient information and education system in 2011, and establishment of whole spine MRI in 2012.

The inclusion criteria were acute traumatic or spontaneous OVFs. Patients with low levels of trauma were also included in the traumatic OVF group.

Vertebral fractures were diagnosed radiologically, by radiologists or spine surgeons. The clinical symptoms back pain, sciatica, and paresis were noted in the emergency department during physical examination. Sciatica was defined as radicular pain radiating out to the leg. Paresis was defined as a degree of muscular strength of Janda 4 or lower, or worsening of a previously known paresis by one degree of Janda. DXA or quantitative computed tomography (qCT) was performed to measure the bone mineral density in the lumbar spine and both femoral necks where applicable. Not all patients underwent all assessments.

We defined concomitant AOVFs as being at least 2 acute STIR-positive vertebral fractures in different vertebral bodies (high signal) and T1w low signal in the MRI, which appear simultaneously (Kano et al. Citation2012). The concomitant fractures may be clinically symptomatic or asymptomatic.

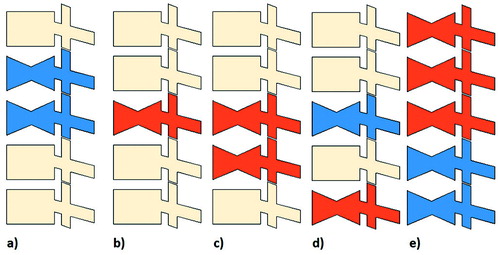

A previous fracture was defined as a STIR-negative vertebral fracture with a change in vertebral geometry of at least 15% height reduction of the front edge of the vertebral body, a deformation of >20% of cover/base-plate, a lesion of the posterior vertebral wall, a scoliotic angle of >10°, or a mono or bisegmental kyphotic or lordotic angle of >15° (Ulmar et al. Citation2010) ( and ).

Figure 1. Examples of single acute, concomitant, and previous fractures. Red: acute fracture; blue: previous fracture. a. 2 previous fractures. b. 1 single acute fracture. c. 2 concomitant fractures. d. 1 acute fracture and 1 previous fracture. e. 3 concomitant fractures and 2 previous fractures.

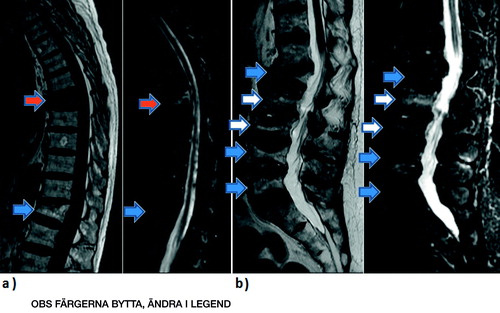

Figure 2. MRI examples for single acute, concomitant, and previous vertebral fractures. a. Patient no. 1 with T1w and STIR images. b. Patient no. 2 with T2w and STIR images. Blue arrow: single acute fracture; red arrow: previous fracture; white arrow: concomitant fracture.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 21.0. Fracture frequencies in the thoracic spine (1st to 9th thoracic vertebral body), the thoracolumbal junction (10th thoracic to 2nd lumbar vertebral body), and the lumbar spine (3rd to 5th lumbar vertebral body) were recorded. Statistically significant differences in frequencies (p < 0.05) were revealed by using the chi-square test for independent data and Cochran’s Q-test for dependent data. Gender differences in the distribution of fracture localization were expressed as frequencies and compared with the chi-square test.

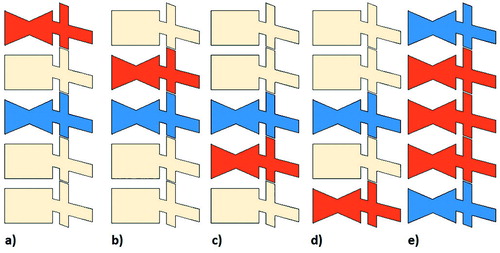

In order to describe the topographic relationship between single acute or concomitant acute fractures and previous OVFs, we defined 5 groups: cranially adjacent fracture (an AOVF is situated cranially adjacent to the previous fracture), cranial gap fracture (an AOVF is situated cranial to the previous fracture with at least 1 healthy vertebral body between the 2 fractured vertebral bodies), caudal adjacent fracture (an AOVF is situated caudally adjacent to the previous fracture), caudal gap fracture (an AOVF is situated caudal to the previous fracture with at least 1 healthy vertebral body between the 2 fractured vertebral bodies), and pliers fracture (all vertebral bodies between 2 previous fractured vertebral bodies are acutely fractured) ().

Figure 3. Location of acute osteoporotic fractures following previous fractures. Red: acute fracture; blue: previous fracture. a. Cranial gap fracture. b. Cranial adjacent fracture. c. Caudal adjacent fracture. d. Caudal gap fracture. e. Pliers fracture.

Logistic regression was performed to investigate the influence of the number of previous fractures (numeric variable), age (numeric variable), sex (dichotomous variable), DXA T-score (numeric variable), lower back pain (dichotomous: 0 = no pain, 1 = pain), sciatica (dichotomous: 0 = no sciatica, 1 = sciatica), paresis (dichotomous:0 = no paresis, 1 = paresis), previous thoracic fractures between T1 and T9 (dichotomous: 0 = no fracture, 1 = fracture), previous thoracolumbar fractures between T10 and L2 (dichotomous: 0 = no fracture, 1 = fracture), and previous lumbar fractures between L3 and L5 (dichotomous: 0 = no fracture, 1 = fracture)—on the odds ratio for the onset of concomitant fractures. For this study the calculated odds ratios can be interpreted as an approximation of relative risks, as the initial risk was low and the odds ratios were less than 3 (Davies Citation1998). The goodness-of-fit was determined with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Ethics

Approval was obtained from the hospital study review committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Study population, fracture localization, and T-score

1,005 patients with a mean age of 78 (SD 10) years were included in this study. The most frequently affected age group was that between 75 and 84 years. 664 (66%) spontaneous and 311 (34%) traumatic AOVFs were detected. Information about clinical symptoms on admission was lacking for some patients. The most common symptom in patients with AOVF was back pain (96%). Sciatica was present in 17% of 646 patients examined for sciatica and a paresis was found in 4% of individuals ().

Table 1. Number of fractures and epidemiology

The most common fractured vertebral body was the L1 vertebra, both in the concomitant fracture group with 268 fractures and in the previous fracture group with 212 fractures. The most common fractured spinal region was the thoracolumbar junction in-between T10 and L2, in both the concomitant group with 787 fractures (57%) and the previous group with 740 fractures (50%). The second highest amount of spine fractures was observed in the lumbar region of the spine between L3 and L5, with 382 concomitant fractures (28%) and 409 previous fractures (28%) ().

Table 2. Location of concomitant and previous osteoporotic vertebral fractures (n = 2,874)

The mean T-score was −3.8 (SD 1.1, range: −7.1 to 3.0). The majority of patients had a T-score of between −2.5 and −3.4 (36%).

Frequency of concomitant and previous OVFs

Of the 1,005 patients, 320 presented with a first-time single AOVF without any previous fracture, 428 suffered from a single AOVF following 1 or more previous OVFs, 257 patients had 640 concomitant AOVFs. The total number of previous fractures in the study population was 1,486 in 599 patients. The numbers of fractures and the epidemiology of the study population are given in Supplementary material. From 1,005 study participants with AOVFs, 257 (26%) had at least 1 concomitant AOVF and 599 (60%) had at least 1 previous fracture. Altogether, 2,874 OVFs were included in REPAPORA. 21 patients had an acute fracture of the iliac bone and they were excluded from the study.

Dependence on the localization of concomitant fractures from previous fractures

In patients with previous fractures of the thoracic spine, the most frequently concomitantly affected spinal segment was the thoracolumbar junction (p < 0.01), followed by the thoracic spine (p < 0.01). In patients with previous osteoporotic fractures of the thoracolumbar junction and the lumbar spine, most concomitant spine fractures were located in the thoracolumbar junction (p < 0.01), followed by the lumbar spine (p < 0.01) ().

Table 3. Frequency and location of concomitant fractures following previous fracturesTable Footnotea

The most frequent relationship between previous fractures and AOVFs was with the caudal gap fracture (n = 211 (25%); p < 0.01), followed by the cranially adjacent fracture (n = 198 (24%); p < 0.01), the caudally adjacent fracture (n = 170 (20%); p < 0.01), the cranial gap fracture (n = 170 (20%); p < 0.01), and the pliers fracture (n = 58 (7.0%)).

A higher number of previous fractures reduces the odds ratio (OR) for the occurrence of concomitant fractures (OR =0.86; p = 0.03). In addition, a higher DXA T-score reduced the OR for concomitant fractures (OR =0.72; p = 0.003), i.e. patients with a lower T-score were more likely to suffer from concomitant fractures. Patients with previous fractures of the thoracic spine between T1 and T9 were less likely to suffer from concomitant fractures (OR =0.47; p = 0.007). Patients with sciatica were less likely to suffer from concomitant fractures (OR =0.51; p = 0.04) (see, Supplementary data). The model used in our logistic regression was statistically significant (omnibus test, p = 0.01) and was therefore a good predictor of concomitant fractures; the Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed no lack of fit (p = 0.2). The classification table showed that our model predicted 77% of concomitant fractures.

Sex differences

Women had more concomitant fractures of the thoracic spine and lumbar spine than men (p < 0.01), and men had a higher number of thoracolumbar concomitant fractures (p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study revealed that concomitant and previous fractures are frequently detected in patients with AOVFs. Risk factors for concomitant fractures were a low number of previous fractures and a low T-score. AOVFs after previous fractures were most often caudal gap fractures.

A prospective study on the non-operative management of symptomatic OVFs showed an age distribution and neurological deficit (3% of patients) similar to the results of our REPAPORA study (Shah and Goregaonkar Citation2016). A sex distribution similar to REPAPORA has also been reported (Nolla et al. Citation2001). A T-score similar to what we found was described in a study of European women with vertebral fractures (Bergot et al. Citation2001). The number of vertebral fractures included in REPAPORA is larger than in other epidemiological studies on OVFs (Arboleya et al. Citation2010, Sanfelix-Genoves et al. Citation2010, Herrera et al. Citation2015). Our study population therefore appears to be representative of patients with symptomatic AOVFs.

Our findings indicate that AOVFs occur less frequently than traumatic non-osteoporotic vertebral fractures in the thoracolumbar junction, and more frequently in the lumbar spine (Magerl et al. Citation1994).

The reason for the vulnerability of the thoracolumbar junction derives from the transition from thoracic kyphosis to lumbar lordosis and from the change from the relatively well-fixed thoracic spine to the free lumbar spine (Buhren Citation2001). The definition of the thoracolumbar junction varies in clinical studies between being T10 to L2 (Knop et al. Citation1999, Wood et al. Citation2003, Park et al. Citation2013) and being T11 to L2 (Buhren Citation2001). We defined the thoracolumbar junction as being between T10 and L2, as this is the most frequently used extent of the thoracolumbar junction in clinical studies. Also, in the present study the L1 vertebra was the most common single acute, concomitant, and previously fractured vertebra, followed by T12. In accordance with this, the thoracolumbar junction was the most frequently affected fracture location.

We defined an acute single or concomitant AOVF to be when MRI showed a high STIR and a low T1w signal, whereas previous fractures had a low STIR and a low T1w signal. This is in accordance with radiological standards for differentiation between acute and previous vertebral fractures (Park et al. Citation2013). There are still no standardized international guidelines for image modalities in patients with AOVFs and the German Osteoporosis Society (DVO) recommends plain radiographs, CT scan, MRI, and scintigraphy—but has not given standards (DVO Citation2014). If clinicians suspect concomitant or occult AOVFs and if patients have risk factors for concomitant fractures, an MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine would appear to be time- and cost-effective for diagnosis of concomitant AOVFs, as more than 99% of all OVFs in our study occurred in these spinal regions. A study on multiple vertebral compression fractures also recommended doing an MRI scan of the thoracic and lumbar spine in patients with osteoporosis and low back pain (Kano et al. Citation2012). Up to 65% of OVFs are overlooked if physicians rule out spine MRI (Park et al. Citation2013). As about 70% of osteoporotic vertebral fractures are asymptomatic or do not show acute onset of pain (Nevitt et al. Citation1998), the clinical usefulness of diagnosing a higher number of OVFs is questionable.

It is generally accepted that a higher number of previous OVFs and a lower bone mineral density are associated with a higher risk of further osteoporotic fractures in general, and OVFs in particular (Lips Citation1997, Cummings and Melton Citation2002, Kemmler et al. Citation2013). Knowing about risk factors for concomitant AOVFs could help physicians reduce the number of overlooked occult AOVFs. A high amount of previous fractures decreases the risk of concomitant fractures and increases the risk of single AOVFs. This could be due to a high number of fractured and sclerosed vertebral bodies that reduce the number of vertebral bodies which can easily fracture simultaneously.

The mechanism that leads to the lumbar drift of AOVFs following previous fractures is not fully understood. In studies on spinal load after osteoporotic vertebral wedge fractures treated with vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty, the most important risk factors for subsequent vertebral fractures were the anterior shift of the upper adjacent vertebral body and the spinopelvic imbalance, especially the segmental kyphotic angle (Rohlmann et al. Citation2006, Baek et al. Citation2015). This leads to an increased intradiscal pressure, increased endplate stress, and increased force in the erector spinae—and it induces increased spinal load with higher fracture risk in osteoporotic vertebrae adjacent to augmented vertebrae. Thus, adjacent fractures may not be caused by the altered stiffness of the polymethyl methacrylate- (PMMA-)augmented vertebrae, but mainly by the altered mechanical spinal load (Rohlmann et al. Citation2006, Qin et al. Citation2014). The increased vertebral load after wedge fractures may also be the cause of subsequent adjacent fractures in non-augmented fractured vertebrae. This is supported by a study that evaluated the effect of kyphotic deformity because of a wedge-shaped vertebral fracture. The authors concluded that a T12 vertebral body fracture leads to an increase in stress on adjacent vertebrae, with bimodal peaks in the midthoracic spine and in 2 superior vertebrae (Okamoto et al. Citation2015). By contrast, in REPAPORA the most frequent fracture following a previous fracture was the caudal gap fracture. The slightly but statistically significant increase in fractures in the vertebral bodies below a previous fracture may be due to kyphotic deformity and increased spinal load in the more caudal vertebral bodies, leading to the lumbar drift with more lumbar-localized OVFs.

The women in our study had fractures of the thoracic spine more frequently than men. On the other hand, men had more fractures of the thoracolumbar junction than women. Fractures of the lumbar spine happened more frequently in women than men. The differences in vertebral size and morphology may contribute to the different risks of fracture in the thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar spine in men and women (Bruno et al. Citation2014).

Our study had some limitations. We did not collect data on how previous fractures had been treated. PMMA-augmented patients may have had a higher number of directly adjacent fractures than the other patients. This may have led to an increased number of directly adjacent fractures. Spinal fusion may also change the mechanical characteristics of the spine and influence the fracture location and mechanism. In addition, we did not differentiate between different types of AOVFs, which may vary in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine and influence the type, frequency, and location of subsequent fractures. The main strength of our study was the high number of fractures that were investigated. We believe that the REPAPORA patients were a representative study population for symptomatic AOVFs.

In summary, cncomitant AOVFs and previous fractures are common and are often overlooked. Risk factors for the occurrence of concomitant AOVFs are a low T-score in DXA and a low number of previous fractures. More than 99% of all OVFs happened in the thoracic and lumbar spine. We recommend performing an MRI scan of the thoracic and lumbar spine with STIR and T1w sequences in patients with multiple AOVFs, or suspicion of concomitant AOVFs, in order to detect all acute concomitant fractures and start adequate fracture treatment.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2016.1273644.

ML collected data, performed statistical analysis, interpreted test results, and wrote the manuscript. NB collected data, performed surgery, and reviewed the manuscript. MS developed the study design, collected data, reviewed the manuscript, and performed surgery.

Many thanks to Craig Mullen MD, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada, for proofreading and language editing of this manuscript. A special thanks to Prof. Dr. Tonn, Head of the Department of Neurosurgery, Ludwig-Maximilian-University of Munich, for his assistance in production of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

IORT_A_1273644_SUPP.pdf

Download PDF (19.9 KB)- Arboleya L, Diaz-Curiel M, Del Rio L, Blanch J, Diez-Perez A, Guanabens N, Quesada J M, Sosa M, Gomez C, Munoz-Torres M, Ramirez E, Combalia J, OSTEOXPRESS study investigators. Prevalence of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women with lumbar osteopenia using MorphoXpress(R) (OSTEOXPRESS Study). Aging Clin Exp Res 2010; 22 (5-6): 419–26.

- Baek S W, Kim C, Chang H. The relationship between the spinopelvic balance and the incidence of adjacent vertebral fractures following percutaneous vertebroplasty. Osteoporos Int 2015; 26 (5): 1507–13.

- Bergot C, Laval-Jeantet A M, Hutchinson K, Dautraix I, Caulin F, Genant H K. A comparison of spinal quantitative computed tomography with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry in European women with vertebral and nonvertebral fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 2001; 68 (2): 74–82.

- Biber R, Wicklein S, Bail H J. [Spinal fractures]. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2016; 49(2): 149–59;

- Bruno A G, Broe K E, Zhang X, Samelson E J, Meng C A, Manoharan R, D’Agostino J, Cupples L A, Kiel D P, Bouxsein M L. Vertebral size, bone density, and strength in men and women matched for age and areal spine BMD. J Bone Miner Res 2014; 29 (3): 562–9.

- Buhren V. [Injuries of the thoracic and lumbar spine]. Chirurg 2001; 72 (7): 865–78; quiz 78-9.

- Cummings S R, Melton L J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 2002; 359 (9319): 1761–7.

- Davies H. When can odds ratios mislead? BMJ 1998; 28 (316): 989–91.

- DVO. DVO Leitlinie Osteoporose 2014 Kurzfassung und Langfassung. Dachverband Osteologie [serial online] 2014 Nov [cited 2016 Mar 21]; 1(1): [1-250 screens]. Available from https://www.laekb.de/files/14BC112BB91/DVO_Leitlinie_18092014.pdf.

- Herrera A, Mateo J, Gil-Albarova J, Lobo-Escolar A, Artigas J M, Lopez-Prats F, Mesa M, Ibarz E, Gracia L. Prevalence of osteoporotic vertebral fracture in Spanish women over age 45. Maturitas 2015; 80 (3): 288–95.

- Kano S, Tanikawa H, Mogami Y, Shibata S, Takanashi S, Oji Y, Aoki T, Oba H, Ikegami S, Takahashi J. Comparison between continuous and discontinuous multiple vertebral compression fractures. Eur Spine J 2012; 21 (9): 1867–72.

- Kemmler W, Haberle L, von Stengel S. Effects of exercise on fracture reduction in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2013; 24 (7): 1937–50.

- Knop C, Blauth M, Buhren V, Hax P M, Kinzl L, Mutschler W, Pommer A, Ulrich C, Wagner S, Weckbach A, Wentzensen A, Worsdorfer O. [Surgical treatment of injuries of the thoracolumbar transition. 1: Epidemiology]. Unfallchirurg 1999; 102 (12): 924–35.

- Lips P. Epidemiology and predictors of fractures associated with osteoporosis. Am J Med 1997; 103 (2A): 3S–8S; discussion S-11S.

- Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein S D, Harms J, Nazarian S. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J 1994; 3 (4): 184–201.

- Nevitt M C, Ettinger B, Black D M, Stone K, Jamal S A, Ensrud K, Segal M, Genant H K, Cummings S R. The association of radiographically detected vertebral fractures with back pain and function: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128 (10): 793–800.

- Nolla J M, Gomez-Vaquero C, Romera M, Roig-Vilaseca D, Rozadilla A, Mateo L, Fiter J, Juanola X, Rodriguez-Moreno J, Valverde J, Roig-Escofet D. Osteoporotic vertebral fracture in clinical practice. 669 Patients diagnosed over a 10 year period. J Rheumatol 2001; 28 (10): 2289–93.

- Okamoto Y, Murakami H, Demura S, Kato S, Yoshioka K, Hayashi H, Sakamoto J, Kawahara N, Tsuchiya H. The effect of kyphotic deformity because of vertebral fracture: a finite element analysis of a 10 degrees and 20 degrees wedge-shaped vertebral fracture model. Spine J 2015; 15 (4): 713–20.

- Park S Y, Lee S H, Suh S W, Park J H, Kim T G. Usefulness of MRI in determining the appropriate level of cement augmentation for acute osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J Spinal Disord Tech 2013; 26 (3): E80–5.

- Qin D A, Song J F, Wei J, Shao J K. [Analysis of the reason of secondary fracture after percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures]. Zhongguo Gu Shang 2014; 27 (9): 730–3.

- Rohlmann A, Zander T, Bergmann G. Spinal loads after osteoporotic vertebral fractures treated by vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty. Eur Spine J 2006; 15 (8): 1255–64.

- Sanfelix-Genoves J, Reig-Molla B, Sanfelix-Gimeno G, Peiro S, Graells-Ferrer M, Vega-Martinez M, Giner V. The population-based prevalence of osteoporotic vertebral fracture and densitometric osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over 50 in Valencia, Spain (the FRAVO study). Bone 2010; 47 (3): 610–6.

- Shah S, Goregaonkar A B. Conservative Management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures: a prospective study of thirty patients. Cureus 2016; 8 (3): e542.

- Ulmar B, Guhring M, Schmalzle T, Weise K, Badke A, Brunner A. Inter- and intra-observer reliability of the Cobb angle in the measurement of vertebral, local and segmental kyphosis of traumatic lumbar spine fractures in the lateral X-ray. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130 (12): 1533–8.

- Wood K, Buttermann G, Mehbod A, Garvey T, Jhanjee R, Sechriest V. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of a thoracolumbar burst fracture without neurological deficit. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A (5): 773–81.