Abstract

Purpose — We wanted to examine the potential of the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) Central Register, and evaluate referral and treatment practice for soft-tissue sarcomas in the extremities and trunk wall (STS) in the Nordic countries.

Background — Based on incidence rates from the literature, 8,150 (7,000–9,300) cases of STS of the extremity and trunk wall should have been diagnosed in Norway, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden from 1987 through 2011. The SSG Register has 6,027 cases registered from this period, with 5,837 having complete registration of key variables. 10 centers have been reporting to the Register. The 5 centers that consistently report treat approximately 90% of the cases in their respective regions. The remaining centers have reported all the patients who were treated during certain time periods, but not for the entire 25-year period.

Results — 59% of patients were referred to a sarcoma center untouched, i.e. before any attempt at open biopsy. There was an improvement from 52% during the first 5 years to 70% during the last 5 years. 50% had wide or better margins at surgery. Wide margins are now achieved less often than 20 years ago, in parallel with an increase in the use of radiotherapy. For the centers that consistently report, 97% of surviving patients are followed for more than 4 years. Metastasis-free survival (MFS) increased from 67% to 73% during the 25-year period.

Interpretation — The Register is considered to be representative of extremity and trunk wall sarcoma disease in the population of Scandinavia, treated at the reporting centers. There were no clinically significant differences in treatment results at these centers.

The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) Central Register was started in 1986. The aim was to make it population-based, like the Southern Sweden Sarcoma Register (Gustafson Citation1994). The purpose of this report is to summarize the status of extremity/trunk wall soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) diagnosis and treatment in the participating countries.

The Nordic population of approximately 27 million people can be identified based on personal identification numbers. There has been less internal migration than in North America, the health system is public, and there is a tradition of collaboration and data sharing between treatment centers.

True incidence figures of extremity and trunk wall STS are difficult to calculate, as national cancer registries have different definitions of which entities constitute an STS and different definitions of tumor sites and locations. The reported proportion of retroperitoneal/organ-localized STS also varies widely, from 15% (Fletcher et al. Citation2013) to 50% (Toro et al. Citation2006).

Consequently, incidence rates for orthopedic STS vary between 1.4 per 100,000 (Weiss and Goldblum Citation2001) and 4 per 100,000 in the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines (Casali et al. Citation2009) and 4.7 per 100,000 in the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification (Fletcher et al. Citation2013). The Cancer Registry of Norway has suggested a figure of 5.0 per 100,000 for all soft-tissue sarcoma. In the RARECARE project, 76 national cancer registries (45,000 patients) were used to calculate median crude incidence rates for the period 1988 through 2002 (Stiller et al. Citation2013). The rate for soft-tissue sarcoma at all sites was 4.7 per 100,000, and it was 1.5 per 100,000 for extremity/trunk wall-localized tumors. 2 Scandinavian, truly population-based regional registers—in Aarhus (Maretty-Nielsen et al. Citation2013) and Lund (Gustafson Citation1994)—have done incidence calculations. It is notable that these 2 registers have exactly the same incidence figures for extremity/trunk wall STS: 1.8 per 100,000. In these reports, all cases in the regions were actively tracked down—combining hospital registers, national cancer registries, and pathology registries—and quality-evaluated using review pathology for inconsistent cases.

Based on the mean populations of Norway, Finland, Iceland, and Sweden during the period 1987–2011 (19 million) (Haagensen Citation2012) and an annual incidence of STS in the extremities and trunk wall of 1.5–2.0 per 100,000, approximately 8,150 (7,000–9,300) STSs would have occurred in these countries in that period. The Register actually had 6,027 patients, 5,837 of whom had complete registration.

10 sarcoma centers have been reporting to the Register (). From Norway and Sweden, 4 tumor centers (in Stockholm, Oslo, Lund, and Bergen), representing approximately 70% of the Scandinavian population, have been reporting all their cases consistently during the entire period. They treat >90% of patients in their catchment area. 2 centers in Finland, treating approximately 50% of all Finnish sarcomas, have been reporting, and the largest center (in Helsinki) has complete reports. The remaining centers have mostly reported all the patients treated during certain time periods but have not reported them at all during other periods.

Table 1. Total numbers (percentages) of patients registered in 5 time periods since the start of the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register, which includes population data from Norway, Finland, and Sweden

The Register and definitions

Designated physicians at each center are responsible for data collection for the SSG Central Register. From the start, referral practice, diagnostic procedures, pathology diagnoses, and surgical staging (size, depth, site, location, and compartmentalization) were focused on. Treatment variables were detailed for the surgical procedure, but not for chemotherapy or radiation parameters. It was merely recorded whether or not chemotherapy or radiotherapy was given. Since 2005, more details of radiotherapy fractionation and dose have been added. The 2014 registration and follow-up forms are available from the SSG website at http://www.ssg-org.net.

A number of key variables have to be completed to qualify for inclusion in the Register-derived studies ().

Table 2. Variables that must be recorded to qualify for inclusion in the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register for extremity and trunk wall sarcoma

Guidelines for interpretation and variable definitions are also available at the SSG website. At the 2009 revision, 10 mm of healthy tissue or intact fascia was established as the cutoff between marginal and wide margins. Previously, a wide margin was just defined as a "cuff of healthy tissue" or intact fascia in accordance with Enneking’s margin definitions (Enneking et al. Citation1980).

The SSG recommends that patients should be followed for at least 5 years from diagnosis or last relapse. However, 10-year follow-up should be considered for patients aged less than 70 years. Follow-up includes physical examination and chest radiography (conventional or computed tomography (CT)), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the primary tumor site when deemed necessary.

To safeguard against systematic bias when "choosing" patients for reporting, centers were tested for adequate follow-up reporting in 2 time periods: 1987–1989 and 2000–2006. More than 75% of patients followed for >4 years were considered necessary to pass this test. 5 continuously reporting centers (Stockholm, Lund, Helsinki, Oslo, and Bergen) passed the test and were included for outcome analysis of all their cases. 3 centers reported adequate follow-up for >75% of patients during a certain time period, and were included with patients diagnosed before 2000 (Umeå, Linköping, and Trondheim). 2 centers did not pass the test and were excluded for outcome reporting (Gothenburg and Tampere). However, they have reported primary data for most of their patients, and these are included for statistics of the demographic variables.

After this test was passed, 4,090 patients remained for outcome analysis of local recurrence (LR) rates and metastasis-free survival (MFS).

At the 8 centers, including patients treated before 2000, 97% of patients had been followed for more than 4 years. Of the patients treated during 2000–2006 by one of the 5 continuously reporting centers, 87% had been followed for more than 4 years in 2013.

Pathology

Classification of sarcomas is based on the WHO classification system for soft-tissue sarcomas (Fletcher et al. Citation2013) (). As an example of changing terminology, the diagnosis malignant fibrous histiocytoma/undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma became reduced from 40% in the period 1987–1996 to 24% in 2007–2011. Of the 5,837 STS cases, 1,463 (25%) have been peer reviewed by the SSG morphology group. In 1987–1996, 44% of preoperative morphological diagnoses were based on cytology only. In 2007–2011, true-cut biopsies were more often added and only 22% of preoperative diagnoses relied exclusively on cytology. The use of open biopsies became reduced from 24% to 4.4% during the 25-year period. This change—of using more true-cut biopsies—was caused by the need for ancillary histopathological analyses, including genetic analyses. In the SSG, the grading of sarcomas has been based on a 4-tier grading system, principally based on Brooders’ grading mode (Broders et al. Citation1939) (Bjerkehagen et al. Citation2009). The French Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) system for grading of soft-tissue sarcoma (Coindre Citation2006) is now more widely used. It is recommended by the WHO (Fletcher et al. Citation2013), and has been recorded in the SSG Register since 2006. The gradual introduction of a new grading system has not resulted in any change in the rate of sarcomas that are graded as high-grade malignant, which has been about three-quarters of the total throughout the period (.)

Table 3. Distribution of histological subtypes of sarcomas in different time periods in the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register

Table 4. Distribution of malignancy grades among 5,462 soft tissue sarcomas according to Broders respectively 210 according to FNCLCCTable Footnotea in different time periods. Rare sarcomas, traditionally not graded are excluded

Radiology

For diagnostic tumor imaging, there has been a clear shift during the period 1987–2011 from CT to MRI. A simple protocol based on a study from 1985 (Weekes et al. Citation1985) is still recommended. The tumor size reported to the SSG Central Register was based on the histopathological specimen during the early years, but it is now increasingly based on preoperative MRI.

Statistics

Pearson’s exact chi-squared test was used for comparisons of categorical variables between groups. Metastasis-free survival (MFS) and local recurrence (LR) rates following treatment in a certain time period were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for comparing groups.

For MFS, follow-up was terminated if a patient had a metastasis or died from the disease, which were both considered events. The rest of the patients were censored at their latest follow-up date or at death from unrelated or unknown causes. For LR, follow-up was ended if a patient had a local recurrence, which was considered to be an uncensored event. The rest of the patients were censored at their latest follow-up date or at death. Results are reported using hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

The effects of potential prognostic factors on MFS and LR, at different centers were computed using Cox multiple regression analysis with the likelihood ratio test (). These factors were analysed for 5 centers and each center were then compared to the center with closest to median survival results. Confidence intervals are given in . Differences are illustrated by plotting a standard patients survival curve at different centers. The prognostic factors were sex, age at diagnosis (1-year increments), tumor size (1-cm increments), tumor depth (deeper vs. subcutaneous location) and grade of malignancy (high-grade vs. low-grade). Log-minus-log survival plots were used to confirm proportionality. These factors are shown to be of univariate prognostic value in many studies (Trovik et al. Citation2001). The most common values for the categorical covariates and the mean values for continuous covariates were chosen for the plots.

Any p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data management and all the statistical analyses were performed on anonymized data using PASW Statistics (18.0–23.0) and Medlog.

Ethics and funding

As a retrospective quality-assurance project, the study was approved by the Ombudsman for Privacy in Research, Norwegian Social Science Data Services. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The SSG Central Register was initially (in 1986) granted a general approval for research on sarcoma treatment in Scandinavia. With new standards for research ethics since 2005, patient consent for reporting data to the SSG Central Register has been introduced.

The study was supported by the National Advisory Unit on sarcomas in Norway, and by the Swedish Cancer Society. The SSG Central Register is also supported by the National Advisory Unit on sarcomas in Norway and by the Swedish Cancer Society.

Results

There was a slight male preponderance (at 53%) and median age at diagnosis was 62 (0–103) years. The distributions of these variables did not change in Scandinavia during the years of monitoring.

59% of the patients were referred to a sarcoma center untouched, before any attempt at open biopsy. There was an improvement from 52% during the first 5-year period to 70% during the last 5-year period (). This improvement led to a reduction in the proportion of patients who needed more than 1 operation to obtain adequate margins after primary tumor resection. During the period 1987–1997, 29% of patients needed more than 1 operation. During 2007–2011, that proportion was 19%.

Table 5. Percentage of cases and total number of cases referred to sarcoma center virgin (including fine-needle or coarse-needle biopsy) or after surgical procedures/recurrence in 3 time periods, as reported in the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register

79% of those tumors operated outside a sarcoma center were <5 cm in diameter, and 62% were subcutaneous. SSG guidelines permit removal of small, subcutaneous lipoma-like tumors outside sarcoma centers.

25% of patients still undergo surgery without any preoperative histopathologic examination, including patients operated primarily outside sarcoma centers and those who are operated at a center, based on radiology alone.

The proportion of patients with metastasis identified during diagnosis or in the first month thereafter was 8% in 1987–1996, 8% in 1997–2006, and 10% in 2007–2011. The median size of the tumor recorded at diagnosis, 7 (1–50) cm, did not change between these time periods.

More than 30% of tumors were subcutaneous, a further indication that the Register is representative of the STS population. Significantly more tumors are now registered with intramuscular location (p < 0.001) than 20 years ago ().

Table 6. Site and depth of tumors in soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) cases according to time period, as reported in the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register

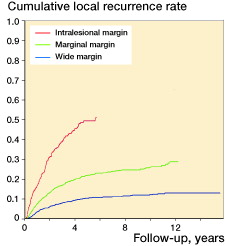

The surgical margin is assessed and determined by the surgeon and the pathologist in collaboration. 56% of patients had wide or better final margins (), but there has been a reduction in wide margins over the study period (p < 0.001). Despite this change, there was less local failure after a marginal/wide margin in patients treated in the period 1997–2011 than in those treated 1987–1996 (p < 0.001). The amputation rate fell from 5.9% in 1987–1996 to 3.5% in 2006–2011 (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Cumulative local recurrence rate according to margins in 4,143 patients treated with curative intent at centers with >4 years of follow-up of more than 75% of surviving patients (p < 0.001). All margins tested against the others. Analysis was terminated at 100 cases left at risk.

At the same time, there has been an increase in the use of radiotherapy, particularly in patients with a wide margin (, ). There is increasing evidence that radiotherapy improves local control regardless of the surgical margins (Trovik 2001, Jebsen et al. Citation2008). 3- and 5-year local recurrence rates (Kaplan-Meier estimates) were 20% and 25%, respectively, in 1987–1996, 12% and 15% in 1996–2006, and 14% (3-year) in 2006–2011. By univariate analysis, local control was correlated to the quality of the surgical margin ().

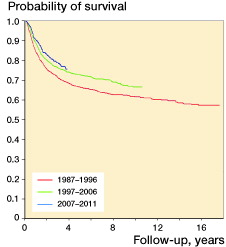

Figure 2 Metastasis-free survival in 4,153 patients surgically treated in 3 time periods at centers with >4 years of follow-up of more than 75% of surviving patients (p < 0.005). The period 1987–1996 was tested against the others. Analysis was terminated at 100 cases left at risk.

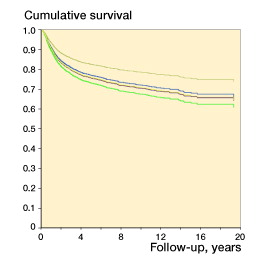

Figure 3. Plot and results from Cox model of metastasis-free survival in 3,842 patients with soft-tissue sarcoma, according to 5 continuously reporting hospitals in the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register. The Cox model included sex, age at diagnosis, tumor size, tumor depth, and malignancy grade. The plots are specified for male sex, age =59 years, tumor size =8.1 cm, deep tumor location, and high grade of malignancy.

Table 7. Final margin distribution (%) and proportion of patients receiving radiation treatment according to margin status among 5,071 patients from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Central Register. The proportion of patients with a wide margin decreased (p < 0.001) and the proportion of patients having radiation treatment increased (p < 0.001)

MFS was analyzed in 4,153 patients with no metastasis at diagnosis, who were surgically treated with curative intent at centers with adequate follow-up reporting. Comparing the period 1987–1996 with 1997–2006, 5-year estimated MFS increased from 67% to 73% (p < 0.005). There was no further statistically significant increase when we compared the most recent period (2007–2011) with the previous one ().

To investigate possible lasting differences in outcome between centers, we compared the rate of MFS among the 5 continuously reporting centers. There was no difference between these centers concerning treatment approach, and at all centers more than 95% of the patients who were referred were treated surgically for their primary tumors. Possible differences in the distribution of prognostic factors in the patient materials were corrected for in a Cox multiple regression analysis. Hazard ratios for 4 centers were tested for significance against the center with MFS results closest to the median (the reference center). 1 center differed significantly from the others ().

Data for evaluation of overall survival and local recurrence-free survival are not as reliable in the Register, as post-metastasis treatment and events are not systematically recorded.

Discussion

This is an overview of diagnosis and treatment results for the extremity and trunk wall soft-tissue sarcoma patients in 4 Nordic countries over 25 years. The SSG Central Register can also be used to evaluate the Scandinavian model of organization of care. Of the centers that continuously report, some with a catchment population of 1–1.5 million inhabitants and some with more than 3.5 million are represented. The treatment results are similar in the different participating centers.

The MFS appeared to be better at the smallest center than at the reference center, but even though statistically significant, the confidence intervals almost overlapped and the clinical significance is uncertain. Comparisons of results between centers must be interpreted with care. Even though these analyses are based on a close to population-based amount of cases, more than 25 years of observation may be needed for a regression to the mean for small centers. An apparent trend in survival analysis could also have been influenced by the longer follow-up of all relapse-free survivors at the smaller centers, even if all the centers recorded all their relapse cases. There were also important demographic differences, differences in the distribution of missing variables, and differences in the completeness of registration of cause of death.

3-year local recurrence rates for the entire period (12–18%) were similar between centers.

It has been reported that treatment guidelines are followed more closely at larger centers (Nijhuis et al. Citation2001), and that results are better (Gutierrez et al. Citation2007), but the definition of a large center in these studies has been generous (> 10 new patients per year), and these were compared with very small centers (< 1 case per year on average). All the Scandinavian centers are large enough to be able to run a multidisciplinary sarcoma team (MDT) (with more than 25 new sarcoma cases a year), and there appear to be similar results at all centers. When there is cooperation among the centers, the Scandinavian model of 10–12 centers each with a catchment population of 1–4 million inhabitants may represent a well-functioning balance between centralized expertise and practical referral distances.

Even though the use of chemotherapy has increased over the years (Jebsen et al. Citation2011), the slightly better survival is most likely due to better centralization to sarcoma centers where treatment decisions are made by the MDT (El Saghir et al. Citation2014). Scandinavian sarcoma care was among the first tumor services to emphasize centralization to MDT boards and to use them as vital instruments for decision making. The main surgical achievements that have resulted from centralization of care to sarcoma centers are less amputations, fewer operations, and better local control.

Median tumor size at diagnosis was constant, although a reduction in size may be masked by more reliance on MRI measurements preoperatively in recent years, compared to pathologist measurements in the early years. In later years, more tumors have been classified as intramuscular, but this too may have been due to better classification by MRI rather than to less extensive growth at diagnosis.

Surprisingly, the proportion of patients with metastasis at diagnosis was unchanged during the study period. This may reflect that metastasis is more related to tumor biology than to tumor size, or it may reflect early detection due to routine use of chest CT. CT is still not mandatory at initial staging of sarcoma patients in Scandinavia, but is being increasingly used.

The mainstay of soft-tissue sarcoma treatment is surgical excision. Important differences concerning the use of adjuvant therapy still exist today. The Scandinavian countries have traditionally used less adjuvant therapy, especially less adjuvant radiotherapy than North American centers (and lower doses of radiotherapy).

There appears to be a changing attitude among Scandinavian surgeons concerning the importance of a wide margin, parallel to the increase in the use of radiotherapy. Wide margins are achieved less often than they were 20 years ago, despite a reduction in numbers of patients who are referred after operations or open biopsies. The classification of margins is coherent across centers (Trovik et al. Citation2012). The local recurrence rates being related to the various types of margins highlights the relevance of this classification, and the reliability of the margin assessments in a Scandinavian setting ().

MRI provides precise measurements and better anatomical resolution, leading to the use of closer margins—i.e. more marginal margins than wide margins. Local control after a marginal/wide margin has, however, improved over the years, indicating that this change of attitude in combination with increased use of radiotherapy can be justified.

As more extensive use of radiotherapy has been introduced in Scandinavia, the associated increased risk of radiation-induced sarcoma should be monitored closely by the Register (Bjerkehagen et al. Citation2013).

Since the creation of the SSG Central Register, numerous other registry-based publications have described demographic parameters for sarcoma patients and prognostic factors for outcome—sometimes based on more than 25,000 patients (Jacobs et al. Citation2015, Ng et al. Citation2013). The original ambition of the SSG, to contribute to the general knowledge of the disease, can therefore be regarded as having been accomplished. It will now be more interesting to test Register-generated hypotheses using specific treatment protocols. Furthermore, the Register’s main function may be to provide data on well-defined subgroups for genomic and proteomic analyses. Most centers preserve tumor tissue in bio-banks.

When the SSG Central Register published the 10-year results 15 years ago, better compliance of registration was anticipated (Bauer et al. Citation2001). Annual accrual has increased, but the completeness of registration has declined somewhat. 25 years ago, standards of quality were defined by professionals involved in the treatment of sarcoma patients, and the main focus was on treatment results related to referral practice and centralized surgical treatment. In recent years, service-related parameters seem to be more important. Government and administrative bodies are increasingly taking an interest in monitoring decision making and time to diagnostic and treatment procedures, both inside and outside sarcoma centers. But the focus is on time to decision rather than quality of decision. The ambition to do meaningful monitoring of such parameters is crucially dependent on complete reporting. If only those centers that have an adequate organization report to the register, nothing will be known about those that really need to be monitored.

We thank all our colleagues at the Scandinavian sarcoma centers for collecting data for the SSG Central Register (Karolinska University Hospital, Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Umeå University Hospital, Linköping University Hospital, Sahlgren University Hospital in Gothenburg, Uppsala University Hospital, Oslo University Hospital, Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, St. Olav’s University Hospital in Trondheim, the University Hospital in Tampere and the University Hospital in Helsinki).

Special thanks to Elisabeth Johansson, Maria Rejmyr, and Eva-Mari Olofsson of the Regional Cancer Center Syd/SSG secretariat for help with data management and for secretarial assistance.

- Bauer H C, Trovik C S, Alvegard T A, Berlin O, Erlanson M, Gustafson P, et al. Monitoring referral and treatment in soft tissue sarcoma: study based on 1,851 patients from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72(2): 150–9.

- Bjerkehagen B, Wejde J, Hansson M, Domanski H, Bohling T. SSG pathology review experiences and histological grading of malignancy in sarcomas. Acta Orthop Scand 2009; 80 (Suppl 334): 31–6.

- Bjerkehagen B, Smastuen M C, Hall K S, Skjeldal S, Bruland O S, Smeland S, et al. Incidence and mortality of second sarcomas - a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(15): 3292–302.

- Broders A C, Hargrave R, Meyerding H W. Pathological features of soft tissue fibrosarcoma with special reference to the grading of its malignancy. Surgery, gynecology and obstetrics 1939; 69: 267–80.

- Casali P G, Jost L, Sleijfer S, Verweij J, Blay J Y, Group EGW. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2009; 20 Suppl 4: 132–6.

- Coindre J M. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006; 130(10): 1448–53.

- El Saghir N S, Keating N L, Carlson R W, Khoury K E, Fallowfield L. Tumor boards: optimizing the structure and improving efficiency of multidisciplinary management of patients with cancer worldwide. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2014: e461–6.

- Enneking W F, Spanier S S, Goodman M A. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980; (153): 106–20.

- Fletcher C D M, Bridge J, Hogendoorn P, Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC; 2013.

- Gustafson P. Soft tissue sarcoma. Epidemiology and prognosis in 508 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1994; Suppl259: 1–31.

- Gutierrez J C, Perez E A, Moffat F L, Livingstone A S, Franceschi D, Koniaris L G. Should soft tissue sarcomas be treated at high-volume centers? An analysis of 4205 patients. Ann Surg 2007; 245(6): 952–8.

- Haagensen K M. Nordic Statistical Yearbook 2012 ISBN 978-92-893-2350-5. 2012.

- Jacobs A J, Michels R, Stein J, Levin A S. Improvement in overall survival from extremity soft tissue sarcoma over twenty years. Sarcoma 2015; 2015: 279601.

- Jebsen N L, Trovik C S, Bauer H C, Rydholm A, Monge O R, Hall K S, (all authors) Radiotherapy to improve local control regardless of surgical margin and malignancy grade in extremity and trunk wall soft tissue sarcoma: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 71(4): 1196–203.

- Jebsen N L, Bruland O S, Eriksson M, Engellau J, Turesson I, Folin A, (all authors). Five-year results from a Scandinavian sarcoma group study (SSG XIII) of adjuvant chemotherapy combined with accelerated radiotherapy in high-risk soft tissue sarcoma of extremities and trunk wall. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 81(5): 1359–66.

- Maretty-Nielsen K, Aggerholm-Pedersen N, Keller J, Safwat A, Baerentzen S, Pedersen A B. Population-based Aarhus Sarcoma Registry: validity, completeness of registration, and incidence of bone and soft tissue sarcomas in western Denmark. Clin Epidemiol 2013; 5: 45–56.

- Ng V Y, Scharschmidt T J, Mayerson J L, Fisher J L. Incidence and survival in sarcoma in the United States: a focus on musculoskeletal lesions. Anticancer Res 2013; 33(6): 2597–604.

- Nijhuis P H, Schaapveld M, Otter R, Hoekstra H J. Soft tissue sarcoma–compliance with guidelines. Cancer 2001; 91(11): 2186–95.

- Stiller C A, Trama A, Serraino D, Rossi S, Navarro C, Chirlaque M D, (all authors). Descriptive epidemiology of sarcomas in Europe: report from the RARECARE project. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(3): 684–95.

- Toro J R, Travis L B, Wu H J, Zhu K, Fletcher C D, Devesa S S. Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1978-2001: An analysis of 26,758 cases. Int J Cancer 2006; 119(12): 2922–30.

- Trovik C S, Scanadinavian Sarcoma Group P. Local recurrence of soft tissue sarcoma. A Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Project. Acta Orthop Scand 2001;72 (Suppl 300): 1–31.

- Trovik C S, Skjeldal S, Bauer H, Rydholm A, Jebsen N. Reliability of margin assessment after surgery for extremity soft tissue sarcoma: The SSG experience. Sarcoma 2012; 2012: 290698.

- Weekes R G, Berquist T H, McLeod R A, Zimmer W D. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft-tissue tumors: comparison with computed tomography. Magn Reson Imaging 1985; 3(4): 345–52.

- Weiss S, Goldblum J. Enzinger & Weiss‚s Soft tissue tumors. 4. ed. Mosby: St Louis 2001.