Abstract

Background and purpose — Metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) as the initial manifestation of malignancy (IMM) limits the time for diagnostic workup; most often, treatment is required before the final primary tumor diagnosis. We evaluated neurological outcome, complications, survival, and the manner of diagnosing the primary tumor in patients who were operated for MSCC as the IMM.

Patients and methods — Records of 69 consecutive patients (51 men) who underwent surgery for MSCC as the IMM were reviewed. The patients had no history of cancer when they presented with pain (n = 2) and/or neurological symptoms (n = 67).

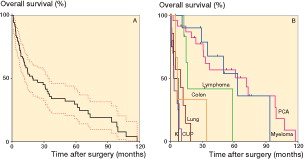

Results — The primary tumor was identified in 59 patients. In 10 patients, no specific diagnosis could be established, and they were therefore defined as having cancer of unknown primary tumor (CUP). At the end of the study, 16 patients were still alive (median follow-up 2.5 years). The overall survival time was 20 months. Patients with CUP had the shortest survival (3.5 months) whereas patients with prostate cancer (6 years) and myeloma (5 years) had the longest survival. 20 of the 39 patients who were non-ambulatory preoperatively regained walking ability, and 29 of the 30 ambulatory patients preoperatively retained their walking ability 1 month postoperatively. 15 of the 69 patients suffered from a total of 20 complications within 1 month postoperatively.

Interpretation — Postoperative survival with MSCC as the IMM depends on the type of primary tumor. Surgery in these patients maintains and improves ambulatory function.

Metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) affects approximately 2.5–5% of all patients with cancer (Loblaw et al. Citation2003, Cole and Patchell Citation2008). It is most common in patients with known cancer, but it may also be the initial manifestation of malignancy (IMM) in a previously unrecognized malignant disease (Schiff et al. Citation1997).

MSCC as the IMM is a challenge for the clinician, who most often requires a decision about treatment before the final primary tumor diagnosis is obtained. Only a few studies have specifically addressed this problem, and these studies had low numbers of patients who underwent surgery (Schiff et al. Citation1997, Aizenberg et al. Citation2012, Quraishi et al. Citation2014). Patients with previously unknown tumors presenting with spinal metastasis may have a different treatment outcome from those with previously unknown tumors presenting with MSCC and progressive neurological symptoms, but the distinction between these 2 entities is not always clear in the literature.

We therefore evaluated patients who had undergone surgical treatment of MSCC as the IMM. The purpose was to determine neurological outcome, complications, survival, and the manner of diagnosing the primary tumor.

Patients and methods

We reviewed the records of 69 consecutive patients who underwent surgery due to MSCC as the IMM at Umeå University Hospital, Sweden, between September 2003 and September 2015. The study is part of a larger prospective morphological study on skeletal metastasis that has been approved by the local ethics review board (no. 223/03, dnr 03-185 and dnr 04-26M). The first 15 consecutive patients in the present study with hormone-naïve prostate cancer were also included in previous studies on MSCC in prostate cancer (Crnalic et al. Citation2011, Citation2012, and Citation2013).

The patients had no history of cancer when they presented with pain (n = 2) and/or neurological symptoms (n = 67). In all patients, the diagnosis of MSCC was confirmed by MRI. 58 of the 69 patients received a high dose of steroids after the onset of neurological symptoms. The surgical, medical, and radiological treatments were performed according to the preferences of the surgical team and the oncological team.

The final tumor diagnosis was obtained based on medical history, clinical examination, laboratory analyses, bone biopsies, and different radiological examinations—which included computed tomography (CT), bone scintigraphy, ultrasound, positron emission tomography (PET), and/or MRI. In 10 patients, no certain diagnosis could be established until they died, so they were defined as having cancer of unknown primary tumor (CUP).

The functional status of the patients before the onset of symptoms of MSCC was estimated retrospectively from the patient records and based on the Karnofsky performance status scale (KPS). Frankel classification was also estimated retrospectively from the patient records in order to determine the neurological function before surgery, and 4 weeks and 6 months after surgery. The follow-up time was defined as the time between the operation and the latest examination or death. Local and systemic complications that occurred within 30 days after surgery were recorded.

Statistics

Postoperative survival was estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis and the survival curves were compared with the log-rank test. Any p-value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 for Windows.

Ethics, funding and potential conflicts of interest

This work was supported by grants from the Cancer Research Foundation in Northern Sweden and the County of Västerbotten. No competing interests declared.

Results

The cohort consisted of 18 women and 51 men with a median age of 72 (50–88) years ().

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 69 patients who underwent surgery for metastatic spinal cord compression as the initial manifestation of malignancy. Values are median (range) or absolute numbers of patients

The anatomic localization of spinal cord compression is shown in .

Table 2. Anatomical location of spinal cord compression confirmed by MRI. Data are numbers of patients

Surgical procedure

23 patients underwent surgery with posterior decompression and 43 patients with posterior decompression and stabilization with pedicle screws, or with pedicle screws and hooks. 3 patients were operated on with an anterior approach using fusion plate and corpectomy; 2 of these patients had a cervical lesion and 1 had a thoracic lesion.

Neurological function

30 of the 69 patients were ambulatory (Frankel D–E) before surgery, and 29 of these retained their walking ability 1 month after surgery (). 1 month after surgery, 49 patients could walk, so 20 of the 39 patients who had been non-ambulatory (Frankel B-C) before surgery had regained the ability to walk. 48 of the 69 patients were still alive 6 months after surgery. 2 patients who were ambulatory at 1 month had lost their ambulatory function after 6 months (1 CUP patient and 1 prostate cancer patient). 1 patient with myeloma who was non-ambulatory at 1 month after surgery had regained ambulatory function at 6 months.

Table 3. Frankel classification of neurological functionTable Footnotea. Data are numbers of patients

The rate of regained ambulatory function was particularly high in patients with prostate cancer; i.e. 19 of 24 patients were non-ambulatory before surgery and 13 of these had regained ambulatory function 1 month after surgery (Figure 1, see Supplementary data).

Complications

15 of the 69 patients suffered from a total of 20 complications within 1 month after surgery. Systemic complications occurred in 5 patients and local complications occurred in 7 patients. 3 patients had both systemic and local complications (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Survival

The median overall survival after surgery (n = 69) was 20 (1.2–107) months. The survival varied depending on the tumor type: prostate cancer, 72 (1.4–118) months; myeloma, 63 (4.8–94) months; lymphoma, 16 (13–59) months; lung cancer, 9 (1.2–19) months; colon cancer, 7 (5–34) months; kidney cancer, 5 (1.2–8) months; and CUP, 3.5 (1.3–11) months ( and ). At the end of the study, 16 patients were still alive with a median follow-up time of 30 (1.4–76) months.

Figure 2. Survival after surgery. A. All patients (n = 69); error bars show 95% CI. B. According to the tumor type. K: kidney cancer (n = 4); CUP: cancer of unknown primary tumor (n = 10); lung cancer (n = 7); colon cancer (n = 3); lymphoma (n = 6); myeloma (n = 11); and PCA: prostate cancer (n = 24). Other tumors not included in the graph: breast cancer (n = 1), thyroid cancer (n = 1), sarcoma (n = 1), and epithelioid mesothelioma (n = 1).

Recurrence of MSCC

12 patients had recurrence of MSCC at 4.5 (2–14) months after surgery, which was confirmed by MRI. In 6 patients (with CUP, colon cancer, lung cancer, myeloma, prostate cancer, sarcoma), recurrence of MSCC occurred at the same spinal level as initial MSCC, whereas in 6 patients (2 CUP, 2 lymphoma, and 1 each with colon cancer and lung cancer), MSCC occurred at another spinal level. 2 patients underwent surgical treatment and 5 patients were treated with radiotherapy only. In 5 patients, recurrence of MSCC occurred in the late phase of their disease and they were therefore offered palliative care only, due to heavy tumor burden.

Identification of the primary site

The primary tumor was identified in 59 of the 69 patients. 11 different types of malignancies were diagnosed, with prostate cancer being the most frequent (Tables 1 and 5). No primary sites could be defined by anamnesis or physical examination. Laboratory samples were most useful in patients with prostate cancer and myeloma. All patients with myeloma had a positive M protein test in serum or urine electrophoresis. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels were increased in all patients with prostate cancer. Chest and abdominal CT was performed in 48 patients, with suspected findings of a primary tumor in 16 of these patients. All patients who were later defined as having CUP were examined with CT. CT scan detected all 4 tumors in the kidney and 5 of 7 lung cancers. During surgery, bone biopsies from the metastatic site were performed in all patients and 65 of these had positive findings (Table 5, see Supplementary data). For the patients with CUP, the biopsy showed adenocarcinoma in 5 patients, poorly differentiated cancer in 2, undifferentiated cancer in 1, squamous cell carcinoma in 1, and clear cell carcinoma in 1 patient.

Discussion

Progression of neurological symptoms due to impending spinal cord compression in patients presenting with MSCC as the IMM usually limits the time for preoperative diagnostic workup. We found that the postoperative survival in these patients was highly dependent on the type of primary tumor.

In the existing literature, patients with MSCC as the IMM have rarely been analyzed as a clearly distinguishable group. Most previous studies of a similar nature have focused on metastases from unknown primary cancer, and have used such terms also when the primary tumor was identified in postoperative diagnostic workup. Some studies have also included patients with spinal metastasis with or without MSCC in the same group (Schiff et al. Citation1997, Aizenberg et al. Citation2012, Quraishi et al. Citation2014). Our findings support the results of other studies (Aizenberg et al. Citation2012, Quraishi et al. Citation2014) that have suggested that the prognosis differs between patients whose primary tumor is located and patients whose primary tumor remains unknown.

Our patients with MSCC as the first sign of malignancy were a heterogeneous group with various primary tumors with inherently different prognoses. In the present study, the overall median survival time was almost 20 months. 2 previous studies on patients with a spinal metastasis of unknown primary tumor, or MSCC as a result of an unknown primary tumor, have reported postoperative survival of 7 and 8 months (Aizenberg et al. Citation2012, Quraishi et al. Citation2014). The difference may be explained to some extent by the different patient material with a high percentage of patients with prostate cancer, myeloma, and lymphoma—and consequently by a higher detection rate of primary tumors in our study. Although the median overall survival in our study well exceeded the recommended life expectancy limit of 3 or 6 months for surgical treatment of MSCC (White et al. Citation2008, George et al. Citation2015), it varied widely according to the type of the primary tumor. This variation may be related to effects of adjuvant therapies, as suggested by Aizenberg et al. (Citation2012), particularly in prostate cancer, myeloma, and lymphoma. In our study, patients with hormone-naïve prostate cancer had the longest survival after surgery, in accordance with previous studies (Huddart et al. Citation1997, Jansson and Bauer Citation2006, Crnalic et al. Citation2011 and 2012). The poor median survival of patients in the CUP group—of 3.5 months in our series—is similar to an average survival of 2.6 months after surgery (Enkaoua et al. Citation1997) or a median survival of 4 months after radiotherapy (Rades et al. Citation2007) for MSCC from CUP. This may be explained by these tumors being aggressive and poorly differentiated, with no therapy available. Interestingly, in a study by Aizenberg et al. (Citation2012) the median survival after diagnosis of spine metastasis was 8 months in patients with CUP.

Our findings highlight the importance of the diagnostic workup to find the primary tumor. The detection rate for the primary tumor in our study was 85%, which is similar to the rate of 89% in the study by Takagi et al. (Citation2015), who focused on detection of bone metastases of unknown origin in general, and to the rate of 96% in patients with spinal metastasis in the study by Iizuka et al. (Citation2009). Interestingly, Quraishi et al. (Citation2014) achieved definitive primary tumor diagnosis in 59% of patients and Aizenberg et al. (Citation2012) in only 31% of patients with unknown tumors that had metastasized to the spine.

As in previous studies (Iizuka et al. Citation2009, Takagi et al. Citation2015), we found that specific tumor markers, chest and abdominal CT, and bone biopsy were useful in order to find the primary tumor. All our patients with myeloma had a positive M protein result in serum or urine electrophoresis, and the PSA levels were elevated in all of our patients with prostate cancer. Chest and abdominal CT identified a suspected primary tumor in 1 of 3 of the patients examined, and it detected the majority of lung and kidney cancers. Similarly, Iizuka et al. (Citation2009) reported that chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT could identify the primary site in 40% of patients with spinal metastasis of unknown origin. Bone biopsy, previously reported to be the most effective way of identifying lymphoma and myeloma (Iizuka et al. Citation2009, Takagi et al. Citation2015), identified all hematological tumors in our study.

The generally high Karnofsky score in our study indicates that patients with a good performance status were more likely to undergo surgery than those with poorer health, and this selection may have influenced the survival data. However, despite the good performance status of our patients, the complication rate was relatively high (22%) and was similar to the complication rates generally reported after surgery for MSCC (Finkelstein et al. Citation2003, Fehlings et al. Citation2016). This further emphasizes the importance of careful selection of patients for surgery.

The treatment for MSCC is mainly palliative, with the primary aim of maintaining or improving quality of life and neurological function. It has been reported that decompressive spinal surgery alone or followed (in conjunction) by radiotherapy is associated with improved ambulatory status (Klimo et al. Citation2005, Patchell et al. 2005, Lee et al. Citation2014) and health-related quality of life (Fehlings et al. Citation2016) in patients with MSCC caused by known primary tumors. However, little is known about the results in patients with MSCC as the IMM. In our study, ambulatory function was improved after surgery in half of the non-ambulatory patients, and it was maintained in almost all ambulatory patients. The latter result is in accordance with 2 previous studies (Aizenberg et al. Citation2012, Quraishi et al. Citation2014). Biological factors such as type of primary tumor have previously been reported not to have any influence on the ambulatory outcome of surgery for MSCC (Chaichana et al. Citation2009). However, in the present study, prostate cancer patients had a particularly good chance of regaining ambulatory function. This may be related to the positive response of these hormone-naïve tumors to surgical castration resulting in reduction of spinal tumor volume.

Interestingly, our study included only 1 patient with MSCC as the presenting sign of breast cancer. One possible explanation may be the Swedish breast cancer-screening program for early detection, which may have contributed to the early diagnosis of primary tumors. It has also been reported that breast cancer patients have the longest time delay from diagnosis of the primary tumor to development of spinal cord compression (Helweg-Larsen et al. Citation2000). Similarly, the high percentage of patients with prostate cancer in this series may be related to the lack of routine screening for PSA in our region.

The present study had several limitations. It was a retrospective observational study. During the study period, there were no strict treatment guidelines for patients with MSCC at our hospital. Thus, the surgical and medical treatments were not randomized and were performed in line with the preferences of the surgical and oncology teams. Furthermore, a long period of data collection (12 years) was another limitation, as advances in diagnostic techniques may have increased the rate of detection of primary tumors during the study period, and newly developed adjuvant therapies may have influenced the survival. The main strength of the study was that it described surgical outcome for consecutive series of a large group of patients, with spinal cord compression as the first sign of previously unknown malignancy.

In summary, our findings indicate that surgery can maintain and improve ambulatory function in patients with MSCC as the IMM. The postoperative survival was highly dependent on the type of primary tumor. This highlights the importance of diagnostic workup before or after surgery in order to select patients for adjuvant therapies, which may have an important impact on survival.

Supplementary data

Tables 4 and 5 and Figure 1 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1319179.

Study design: JW, PGr, PGu, and SC. Data analysis: JW, PGr, HN, AB, and SC. Preparation of the manuscript: all authors.

IORT_A_1319179_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (134.7 KB)- Aizenberg M R, Fox B D, Suki D, McCutcheon I E, Rao G, Rhines L D. Surgical management of unknown primary tumors metastatic to the spine. J Neurosurg Spine 2012; 16: 86–92.

- Chaichana K L, Pendleton C, Sciubba D, Wolinsky J P, Gokaslan Z. Outcome following decompressive surgery for different histological types of metastatic tumors causing epidural spinal cord compression. J Neurosurg Spine 2009; 11: 56–63.

- Cole J S, Patchell R A. Metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 459–66.

- Crnalic S, Hildingsson C, Wikstrom P, Bergh A, Löfvenberg R, Widmark A. Outcome after surgery for metastatic spinal cord compression in 54 patients with prostate cancer. Acta Orthop 2011; 83(1): 80–6.

- Crnalic S, Löfvenberg R, Bergh A, Widmark A, Hildingsson C. Predicting survival for surgery of metastatic spinal cord compression in prostate cancer: a new score. Spine 2012; 37: 2168–76.

- Crnalic S, Hildingsson C, Bergh A, Widmark A, Svensson O, Löfvenberg R. Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial for neurological recovery after surgery for metastatic spinal cord compression in prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 2013; 52: 809–15.

- Enkaoua E A, Doursounian L, Chatellier G, Mabesoone F, Aimard T, Saillant G. Vertebral metastases – a critical appreciation of the preoperative prognostic Tokuhashi score in a series of 71 cases. Spine 1997; 22: 2293–8.

- Fehlings M G, Nater A, Tetreault L, Kopjar B, Arnold P, Dekutoski M, Finkelstein J, Fisher C, France J, Gokaslan Z, Massicotte E, Rhines L, Rose P, Sahgal A, Schuster J, Vaccaro A. Survival and clinical outcomes in surgically treated patients with metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: results of the prospective multicenter AOSpine study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 268–76.

- Finkelstein J A, Zaveri G, Wai E, Vidar M, Kreder H, Chow E. A population-based study of surgery for spinal metastases: survival rates and complications. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2003; 85: 1045–50.

- George, R, Jeba J, Ramkumar G, Chacko A G, Leng M, Tharyan P. Interventions for the treatment of metastatic extradural spinal cord compression in adults. Cochrane Database SystRev 2015; 9: p. CD006716

- Helweg-Larsen S, Sorensen P, Kreiner S. Prognostic factors in metastatic spinal cord compression: a prospective study using multivariate analysis of variables influencing survival and gait function in 153 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 46: 1163–9.

- Huddart R A, Rajan B, Law M, Meyer L, Dearnaley D P. Spinal cord compression in prostate cancer: treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Radiother Oncol 1997; 44(3): 229–36.

- Iizuka Y, Iizuka H, Tsutsumi S, Nakagawa Y, Nakajima T, Sorimachi Y, Ara T, Nishinome M, Seki T, Takagishi K. Diagnosis of a previously unidentified primary site in patients with spinal metastasis: diagnostic usefulness of laboratory analysis, CT scanning and CT-guided biopsy. Eur Spine J 2009; 18: 1431–5.

- Jansson K A, Bauer H C. Survival, complications and outcome in 282 patients operated for neurological deficit due to thoracic or lumbar spinal metastases. Eur Spine J 2006; 15(2): 196–202.

- Klimo P Jr, Thompson C J, Kestle J R, Schmidt MH . A meta-analysis of surgery versus conventional radiotherapy for the treatment of metastatic spinal epidural disease. Neuro Oncol 2005; 7(1): 64–76.

- Lee C H, Kwon J W, Lee J, Hyun S J, Kim K J, Jahng T A, Kim H J. Direct decompressive surgery followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: a meta-analysis. Spine 2014; 39(9): E587–E592.

- Loblaw D A, Laperriere N J, Mackillop W J. A population-based study of malignant spinal cord compression in Ontario. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2003; 15(4): 211–17.

- Rades D, Fehlauer F, Veninga T, Stalpers L J A, Basic H, Hoskin P J, Rudat V, Karstens J H, Schild S E, Dunst J. Functional outcome and survival after radiotherapy of metastatic spinal cord compression in patients with cancer of unknown primary. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 67: 532–7.

- Schiff D, O’Neill B P, Suman V J. Spinal epidural metastasis as the initial manifestation of malignancy. Neurology 1997; 49: 452–6.

- Takagi T, Katagiri H, Kim Y, Suehara Y, Kubota D, Akaike K, Ishii M, Mukaihara K, Okubo T, Murata H, Takahashi M, Kaneko K, Saito T. Skeletal metastasis of unknown primary origin at the initial visit: A retrospective analysis of 286 cases. PlosOne DO: 2015: 10.1471

- Quraishi N A, Ramoutar D, Manoharan S R, Spencer A, Arealis G, Edwards K L, Boszczyk BM . Metastatic spinal cord compression as a result of the unknown primary tumor. Eur Spine J 2014; 23: 1502–7.

- White B D, Stirling A J, Paterson E, Asquith-Coe K, Melder A. Diagnosis and management of patients at risk of or with metastatic spinal cord compression: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2008; 337: a2538.