Abstract

Background and purpose — Routine outcome measurement has been shown to improve performance in several fields of healthcare. National spine surgery registries have been initiated in 5 Nordic countries. However, there is no agreement on which outcomes are essential to measure for adolescent and young adult patients with a spinal deformity. The aim of this study was to develop a core outcome set (COS) that will facilitate benchmarking within and between the 5 countries of the Nordic Spinal Deformity Society (NSDS) and other registries worldwide.

Material and methods — From August 2015 to September 2016, 7 representatives (panelists) of the national spinal surgery registries from each of the NSDS countries participated in a modified Delphi study. With a systematic literature review as a basis and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework as guidance, 4 consensus rounds were held. Consensus was defined as agreement between at least 5 of the 7 representatives. Data were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively.

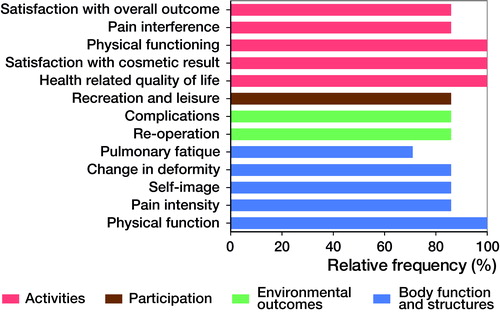

Results — Consensus was reached on the inclusion of 13 core outcome domains: “satisfaction with overall outcome of surgery”, “satisfaction with cosmetic result of surgery”, “pain interference”, physical functioning”, “health-related quality of life”, “recreation and leisure”, “pulmonary fatigue”, “change in deformity”, “self-image”, “pain intensity”, “physical function”, “complications”, and “re-operation”. Panelists agreed that the SRS-22r, EQ-5D, and a pulmonary fatigue questionnaire (yet to be developed) are the most appropriate set of patient-reported measurement instruments that cover these outcome domains.

Interpretation — We have identified a COS for a large subgroup of spinal deformity patients for implementation and validation in the NSDS countries. This is the first study to further develop a COS in a global perspective.

Measurement of quality of life, functioning, and disability outcomes from a patient’s perspective plays an important role in current and future healthcare systems (Porter Citation2010). This also holds for adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients with spinal deformities. In the surgical management of AYA spinal deformities, where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are challenging and often deemed unethical, and where tremendous treatment variability exists, routine outcome monitoring through outcome registries is very valuable for evaluating treatment strategies (Weinstein et al. Citation2009, van Hooff et al. Citation2015). These outcome registries are based on patient-relevant outcomes, i.e. patient-reported outcomes and clinician-based outcomes that matter to patients (Clement et al. Citation2015, van Hooff et al. Citation2015). In each of the five countries associated with the Nordic Spinal Deformities Society (Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, and The Netherlands) such spine outcome registries exist on a national level, but they are predominantly focused on the lumbar spine. Outcome registries are most valuable if they are standardized, comparable between countries, and include outcome measures that are relevant to the patient population of interest (van Hooff et al. Citation2015, Porter et al. Citation2016). Currently, no consensus-based standardized spinal deformity outcomes measure exists for these national registries. The literature on spinal deformities is inundated with multiple measurement instruments used to evaluate a diverse range of treatment outcomes. For example, in the spinal deformity literature, there are 12 different measurement instruments to evaluate shoulder balance, none of which has been universally agreed upon (Qiu et al. Citation2009). This leaves clinicians wondering which measurement instruments are the most appropriate to evaluate outcome after AYA spinal deformity treatment. Therefore, it is of importance to agree internationally upon a core set of outcome domains that are essential to measure in every AYA patient undergoing spinal deformity surgery. The implementation of such a core outcome set (COS) would facilitate comparison across registries and ultimately would improve the quality of daily clinical practice by enabling continuous evaluation and improvement (Porter Citation2010, Porter et al. Citation2016).

The aim of this study was to develop a patient-relevant COS that will facilitate benchmarking within and between the 5 countries of the NSDS and other registries worldwide.

Material and methods

Design

A modified Delphi study was performed, which consisted of a literature review (preparatory stage) and 4 consensus rounds. The day-to-day activities, design, and key aspects of the study were performed by the project team (MdK, SSAF, MH, MLvH, NMG, TMH). This project has been registered in the COMET database (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials, http://www.comet-initiative.org).

Selection of Delphi panelists

During the 2014 annual meeting of the NSDS, the members commissioned the project team to perform this study. 7 representatives of the national spine surgery registries from each of the countries associated with the NSDS (2 from Sweden, 2 from Denmark, and 1 each from Finland, Norway, and the Netherlands) were invited to participate. Each representative had been practicing as a spine surgeon with a focus on AYA spinal deformity for at least 5 years.

Generation of a list of potential core domains and measurement instruments

With the aid of an experienced medical information specialist, a systematic literature search was performed of all surgical deformity studies that involved health-outcome measures. The PubMed, eMBASE.com, Cinahl, and the Cochrane Library databases were searched for articles published between January 1, 2000 and August 5, 2015. Appendix 1 (see Supplementary data) contains the PubMed search strategy (search strategies for the other databases are available on request).

Inclusion criteria:

RCTs, non-randomized trials, and observational cohort studies;

n ≥ 20 participants, aged 10–25 years;

Patient-relevant outcomes were measured and reported;

Patients undergoing surgery.

Exclusion criteria:

Case series or studies with <20 participants;

Studies with solely radiographic or perioperative measures;

Studies on non-operatively treated patients;

Systematic reviews, animal studies, technical descriptions, and papers on the development of measurement instruments;

Studies concerning patients with neuromuscular disorders.

2 reviewers (TMH and MLvH) independently applied the inclusion criteria to the titles and abstracts. If it was ambiguous whether the inclusion criteria were met, the full text article was examined. In any case of disagreement, a third reviewer (MdK) was consulted, who made the final decision.

Quality assessment (Appendix 2, see Supplementary data)

The included papers were subjected to a 4-item risk of bias assessment based on the GRADE (the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) workgroup (Guyatt et al. Citation2011, Guyatt Citation2015): A sum score of ≥3 was regarded as high methodological quality, while a score of <3 was regarded as low methodological quality. Papers were scored independently by 2 reviewers (rotating between SSAF, MLvH, and TMH). In any case of disagreement, the third reviewer was consulted and made the final decision.

A data-extraction form was developed to obtain essential study information including the measurement instruments used to assess patient-related outcomes (e.g. ODI, SRS-22r) as well as single-item measures (e.g. satisfaction with overall treatment). The outcome domains (concepts; e.g. pain, function) measured by each instrument were classified within the main chapters of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF framework) as determined by the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/) (WHO). The ICF framework consists of 5 chapters: Body Function, Activities, Participation, Environmental Factors, and Personal Factors. Data extraction was performed independently by 2 reviewers (SSAF and RMH). Finally, identified measurement instruments were subjected to a clinimetric quality (Terwee et al. Citation2007) (e.g. validity and reliability of the measurement instruments) and feasibility assessment (availability in Nordic languages, license fees, and time to complete).

Modified Delphi procedure

The Delphi study took place between August 2015 and September 2016. The first round was held during a face-to-face meeting at the 2015 NSDS annual meeting in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The remaining 3 rounds were completed through an online survey. In each round, panelists were asked to vote for or against the inclusion of a list of potential core outcome domains. Panelists could provide feedback on the appropriateness of each domain, the terminology and definitions used, and whether important outcome domains were missing. After each round a report was sent to the panelists, which included an overview of the votes, a summary of the panelists’ feedback, and the adaptations made to the list of potential core domains based on the feedback received. This report was also used as input for the subsequent round. The threshold for consensus was set at 5 out of 7 panelists. If consensus was reached and there was agreement with the terminology and definition, the domain was included in the COS and excluded from subsequent rounds. Because a COS should only include the most relevant domains for all patients, domains for which no consensus was achieved were excluded. In the first 3 rounds, consensus was sought on patient-relevant outcome domains, and for round 4, the focus was on outcomes that could be measured using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Based on an analysis of the clinimetric quality and the availability of current PROMs, in round 4, panelists were queried on the measurement instruments that should be used to measure the core outcomes.

Results

Response

All panelists participated in Round 1 (face-to-face meeting) and completed Rounds 2, 3, and 4 (online surveys), achieving a 7/7 response rate for all rounds.

List of potential core domains

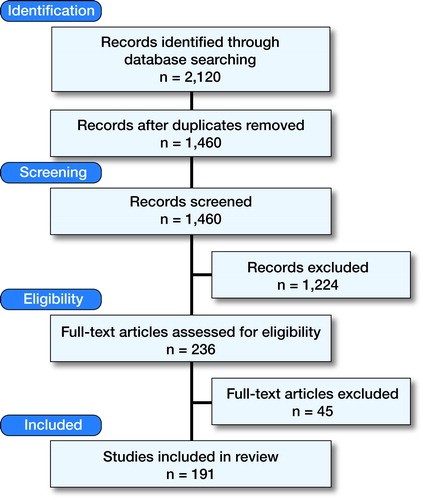

The literature search revealed 2,120 papers. After title, abstract, and full text selection, 191 papers remained for inclusion in the review (). The 191 papers described a total of 26 patient-relevant outcome measures, which measured 40 core outcome domains (Appendix 3, see Supplementary data). The identified outcome domains covered 4 of the 5 ICF chapters, i.e. “Body Function”, “Activities”, “Participation”, and “Environmental Factors”. No outcome domains were identified in the chapter “Personal Factors”. It was often not possible to make a clear distinction whether a domain could be allocated to the chapters “Activities” or “Participation”, and thus in Appendix 3 these 2 chapters are reported together.

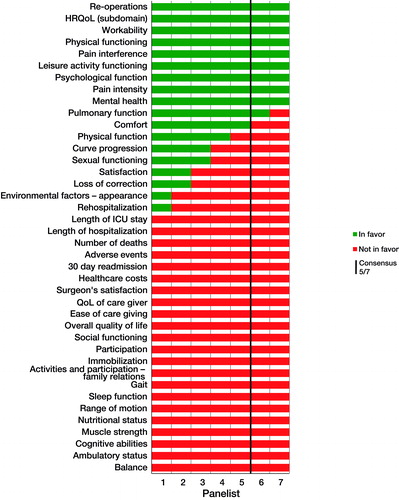

Consensus round 1 ()

Consensus was reached on the inclusion of 11 of 40 identified domains in the COS: “re-operations”, “health-related quality of life (HRQoL)”, “workability”, “physical functioning”, “pain interference”, “leisure activity functioning”, “psychological function”, pain intensity”, “mental health”, “pulmonary function”, and “comfort”. Consensus was reached to not include multiple domains ().

In Round 1, there were extensive discussions concerning the distinction between “quality of life” (QoL) and “HRQoL”, the definition of “pulmonary function” vs. “pulmonary fatigue”, and “overall satisfaction” vs. more specific domains of satisfaction (satisfaction with “outcome”, “treatment service”, “cosmetic results”). Furthermore, panelists requested more information on the difference between the “adverse events” and “complications” domains. A complete overview of the comments and discussion in Round 1 is provided in Appendix 4 (see Supplementary data).

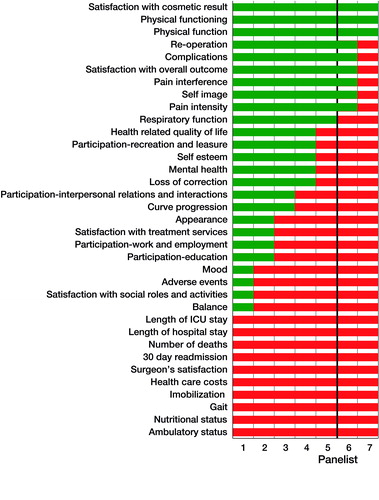

Consensus round 2 ()

Based on the proposed changes and comments provided in Round 1, a list of 35 domains and definitions were presented and voted on in Round 2. Consensus was reached on the inclusion of “satisfaction with cosmetic result”, “physical functioning”, “physical function”, “re-operation”, “complications”, “satisfaction with overall outcome”, “pain interference”, “self-image, “pain intensity”, and “respiratory function”.

In the Round 1 report, attention was given to the difference between “adverse events” (any medical occurrences in the treatment period, not necessarily caused by the treatment) and “complications” (result of the treatment itself). In the literature, complications were more often measured than adverse events.

In Round 2, the panelists regarded “curve progression” and “loss of correction” as similar outcome domains. To address this, these domains were grouped together under “change of deformity”, defined as “progression of the curve or loss of correction from first postoperative measurement to final follow-up as measured by Cobb’s angle”. The definition of respiratory function, adapted based on comments in Round 1, was still confusing. It was not clear if this is measured by PROMs or pulmonary function tests. It was suggested to replace this domain with a patient-reported domain “pulmonary fatigue”. Furthermore, there was debate concerning the overlap between physical function and physical functioning. Although they are often used interchangeably, according to the ICF, a fundamental difference exists between them (WHO). Physical function entails any movement that involves the integration of multiple body systems and structures (e.g. reaching and sitting), while physical functioning focuses on the instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. walking to the bus stop). Consensus was reached that both concepts are essential for spinal deformity patients.

In addition, the domains of “scar length” and “ability to continue with previous activities” (e.g. sports, acting) were also suggested by panelists for inclusion. All suggestions and domains on which no consensus was achieved were included in Round 3.

Consensus round 3 ()

After completion of Round 3, consensus was reached on the inclusion of 13 “core outcome domains” covering four major chapters of the ICF framework, and exclusion of 20 outcome domains (). Of the 13, 10 are patient-reported and 3 are clinician-reported (“reoperation”, complication”, and “loss of correction”). No consensus was reached on the domains of “interpersonal relations and interaction”, “mental health”, “self-esteem”, and “continuation of pervious activities”. In Round 3, panelists did not have further comments.

Table 1. Outcome domains for which consensus is reached to not include in the core outcome set

Round 4

The aim of Round 4 was to establish a clinimetrically sound and comprehensive set of PROMs that would capture the patient-reported core outcome domains identified in the first 3 rounds. Based on the analysis of the clinimetric information (appendix 5, see Supplementary data) and a feasibility assessment (availability in Nordic languages, license fees, and time to complete, appendix 6—see Supplementary data), 2 measurement instruments were proposed by the research team that covered 9 out of the 13 domains:

The SRS-22r, which measures the core outcome domains “self-image”, “physical functioning”, “pain interference”, “physical function”, “pain intensity”, “participation: recreation and leisure”, “satisfaction with the cosmetic result”, and “satisfaction with the overall outcome of surgery”.

The EQ-5D, which measures the core outcome domain “HRQoL”.

The domain of “pulmonary fatigue” that can be patient-reported was not covered.

As no validated measurement instrument was found that measures patient-reported “pulmonary fatigue” for the target population, we propose that a questionnaire to measure this outcome domain be developed.

The remaining 3 domains (“re-operation”, “complications”, and “change in deformity”) are clinician reported, but will need further study to identify the definitions and measurement method.

In Round 4, consensus was reached (6/7 panelists agreed) that this was the set of measurement instruments that is feasible to implement in the Nordic registries and that captures most domains.

Discussion

International consensus on outcome domains and measures is essential for identifying effectiveness of treatments, benchmarking, improving quality, and conducting multicenter studies. Using the methodological guidance of initiatives such as COMET (Prinsen et al. Citation2014), OMERACT (Boers et al. Citation2014) and ICHOM (Clement et al. Citation2015), this study has identified a COS for AYA spine deformity surgery patients for implementation and validation in the Nordic Spine Surgery Registries. It consists of 13 domains and 2 accompanying patient-reported measurement instruments (SRS-22r and EQ5D), which have been agreed upon by representatives of the Nordic Spine Surgery Registries.

The 13 outcome domains defined in this COS cover 4 of 5 main chapters of the ICF framework and correspond with the common symptoms that the target patient group report including back pain, limited range of motion, activity limitations, waistline imbalance, rib prominence, wound/scar problems, and shortness of breath (Spanyer et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, psychological outcomes, such as self-image, are included in the COS, a need that has been emphasized in a previous study for AYA with spinal deformities (Wang et al. Citation2014). Our study highlighted the omission of patient-reported pulmonary fatigue in the literature and proposed to include this domain in the COS, even though no measurement instrument is currently available.

In our study, consensus was also reached on a core set of PROM instruments that were considered to be optimal for measuring 10 of the 13 identified core outcome domains. The PROMs had to be valid, reliable, and feasible to implement. After a review and assessment of the clinimetric literature, consensus was reached to use the SRS-22r, the EQ-5D, and a pulmonary fatigue questionnaire (yet to be developed and validated). The SF-12 scored equal to the EQ-5D on clinimetric quality, feasibility, and acceptance. Nevertheless, the EQ-5D was favored based on its use in health economic evaluations by calculating utilities, its current use in the Nordic lumbar spine registries (thereby contributing to consistency), and because the license fee is waived for non-commercial use for the EQ-5D but not for the SF-12. We recommend that this core set of measurement instruments be regularly updated, as the PROM field is rapidly changing. For example, in the future, computer-adaptive testing based on item response theory (IRT) may be available for spinal deformity patients (e.g. the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®)) (Cella et al. Citation2010, Gershon et al. Citation2010), Alonso et al. Citation2013). The remaining 3 outcome domains identified in the COS (“complications”, “re-operation”, “change in deformity”) are reported by the clinician. During this Delphi study it became clear that it was too early to reach consensus on the exact definitions and measurement methods for the 3 clinician-reported outcome domains. For example, within the spine field, there are ongoing discussions regarding the definitions and measurement of complications and re-operations. In the future, these results could be implemented in the COS presented here. Although deemed important and “core” by our panelists, pulmonary fatigue measures are not common practice in AYA with spinal deformities. To the best of our knowledge, no measures currently exist that are valid and sensitive enough to measure this domain in this patient group.

Strengths and limitations

A limitation of our study is that pre-selected spine surgeons with sufficient influence and knowledge of their country’s spine registry were invited to participate. Although this purposeful sampling increases the risk of selection bias, it also increases the likelihood of uptake and implementation by the respective spine registries.

The target patient group was not involved in the Delphi procedure, which has recently been recommended by methodological papers on COS development and as well by ICHOM methodology (Boers et al. Citation2014, Clement et al. Citation2015). With our partially underage and non-English-speaking patient group, we deemed it infeasible to find adequate patient representatives to participate in the Delphi procedure. An alternative to involving patients in the consensus procedure itself might be to validate, and if necessary adapt, the COS based on a future patient focus-group study.

Strengths include the thorough systematic literature search by a specialized medical information specialist to find potential outcome domains and the clinimetric and feasibility assessment of PROMs, which provided the panelists with up-to-date and high-quality information. An excellent response rate of 7/7 for all rounds was reached. Finally, the ICF framework was used and showed that the proposed COS covers the whole patient experience of having a spinal deformity.

Future perspectives

This is the first step in the development of a global COS that could be used in both outcome registries and research. Additional steps are needed before a global COS can be implemented, which include designing an additional pulmonary fatigue questionnaire, providing the right definition for the 3 clinician-reported outcomes (“re-operation”, “complications”, and “change in deformity”), reaching consensus on the relevant case mix variables to allow for risk stratification, agreeing on the timing of the measurement moments (e.g. 6, 12, or 24 months postoperatively), repeating the Delphi procedure in a global setting, the validation of this “Nordic” COS in settings with different health care systems and cultures, and validation in a representative patient group.

Summary

To our knowledge, this is the first COS that has been developed for a large subgroup of patients with a spinal deformity. The study shows that it is feasible to reach consensus among experts from the Nordic region on which outcomes are most important to measure in the AYA patient group undergoing deformity surgery. A gap in current outcome measurements is identified, namely for pulmonary fatigue. Suggestions are provided for future steps needed to establish a global core outcome set. A globally implemented COS facilitates better pooling of research data. It also facilitates the implementation of high-quality (national) spine deformity surgery registries, which by benchmarking not only nationally, but also internationally, may ultimately improve the value of the care given to our patients.

Supplementary data

Appendices 1–6 are available in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1371371

MdK, TMH, and MvH had the idea for the study. MdK, TMH, MvH, NMG, and DP contributed to the study design. MvH and TMH provided methodological input. MdK and DP provided clinical input. TMH and MvH conducted the search and selection of the papers. SSAF and RMH critically appraised the methodological quality of the studies as well as the clinimetric quality of the derived measurement instruments. MdK, SSAF, RMH, NMG, TMH, and MvH executed the consensus rounds. DP moderated the first consensus round and discussion. MvH, TMH, MdK, and SSAF analyzed the data. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results. MdK, TMH, SSAF, and MvH drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funded by AOSpine through the AOSpine knowledge forum deformity.

No competing interests declared.

We would like to thank Ilse Jansma, librarian and information specialist at the VU University Medical Center, for her help in the design of the search strategy.

We thank the AOSpine Knowledge Forum Deformity for funding this study. AOSpine is a clinical division of the AO Foundation—an independent medically guided nonprofit organization.

The AOSpine Knowledge Forums are pathology focused working groups acting on behalf of AOSpine in their domain of scientific expertise. Each forum consists of a steering committee of up to 10 international spine experts who meet on a regular basis to discuss research, assess the best evidence for current practices, and formulate clinical trials to advance spine care worldwide. Study support is provided directly through AOSpine’s Research department.

Acta thanks Georg Singer and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this study.

IORT_A_1371371_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (61.2 KB)- Alonso J, Bartlett S J, Rose M, Aaronson N K, Chaplin J E, Efficace F, Leplège A, Lu A, Tulsky D S, Raat H, Ravens-Sieberer U, Revicki D, Terwee C B, Valderas J M, Cella D, Forrest C B. The case for an international patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS(R)) initiative. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11: 210.

- Boers M, Kirwan J R, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d’Agostino M A, Conaghan PG, Bingham CO 3rd, Brooks P, Landewé R, March L, Simon L S, Singh J A, Strand V, Tugwell P. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67 (7): 745–53.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S, Cook K, Devellis R, DeWalt D, Fries J F, Gershon R, Hahn E A, Lai J S, Pilkonis P, Revicki D, Rose M, Weinfurt K, Hays R. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63 (11): 1179–94.

- Clement R C, Welander A, Stowell C, Cha T D. Chen J L, Davies M, Fairbank J C, Foley K T, Gehrchen M, Hagg O, Jacobs W C, Kahler R, Khan S N, Lieberman I H, Morisson B, Ohnmeiss D D, Peul W C, Shonnard N H, Smuck M W, Solberg T K, Stromqvist B H, Hooff M L, Wasan A D, Willems P C, Yeo W, Fritzell P. A proposed set of metrics for standardized outcome reporting in the management of low back pain. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (5): 523–33.

- Gershon R C, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas 2010; 11 (3): 304–14.

- Guyatt, G. How to rate risk of bias in observational studies. Retrieved January 9, 2015, from http://help.magicapp.org/knowledgebase/articles/294933-how-to-rate-risk-of-bias-in-observational-studies.

- Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Montori V, Akl E A, Djulbegovic B, Falck-Ytter Y, Norris S L, Williams J W Jr, Atkins D, Meerpohl J, Schunemann H J. GRADE guidelines, 4: Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64 (4): 407–15.

- Porter M E. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010; 363 (26): 2477–81.

- Porter M E, Larsson S, Lee T H. Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N Engl J Med 2016; 374 (6): 504–6.

- Prinsen C A, Vohra S, Rose M R, King-Jones S, Ishaque S, Bhaloo Z, Adams D, Terwee C B. Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative: Protocol for an international Delphi study to achieve consensus on how to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “core outcome set”. Trials 2014; 15: 247.

- Qiu X S, Ma W W, Li W G, Wang B, Yu Y, Zhu Z Z, Qian B P, Zhu F, Sun X, Ng B K, Cheng J C, Qiu Y. Discrepancy between radiographic shoulder balance and cosmetic shoulder balance in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients with double thoracic curve. Eur Spine J 2009; 18 (1): 45–51.

- Spanyer J M, Crawford C H, Canan C E, Burke L O, Heintzman S E, Carreon L Y. Health-related quality-of-life scores, spine-related symptoms, and reoperations in young adults 7 to 17 years after surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Am J Orthop 2015; 44 (1): 26–31.

- Terwee C B, Bot S D, de Boer M R, van der Windt D A, Knol D L, Dekker J, Bouter L M, de Vet H C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60 (1): 34–42.

- van Hooff M L, Jacobs W C, Willems P C, Wouters M W, de Kleuver M, Peul W C, Ostelo RW, Fritzell P. Evidence and practice in spine registries. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (5): 534–44.

- Wang L, Wang Y P, Yu B, Zhang J G, Shen J X, Qiu G X, Li Y. Relation between self-image score of SRS-22 with deformity measures in female adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014; 100 (7): 797–801.

- Weinstein J N, Lurie J D, Tosteson T D, Zhao W, Blood E A, Tosteson A N, Birkmeyer N, Herkowitz H, Longley M, Lenke L, Emery S, Hu S S. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis: Four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (6): 1295–1304.

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning and Disability. Retrieved January 12, 2016, from http://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/