ABSTRACT

Background

Art therapy could benefit couples.

Aims

This article explores art therapy used by couples in relational crisis from a professional perspective.

Methods

Seven art therapists working in family counselling participated in the qualitative study.

Results

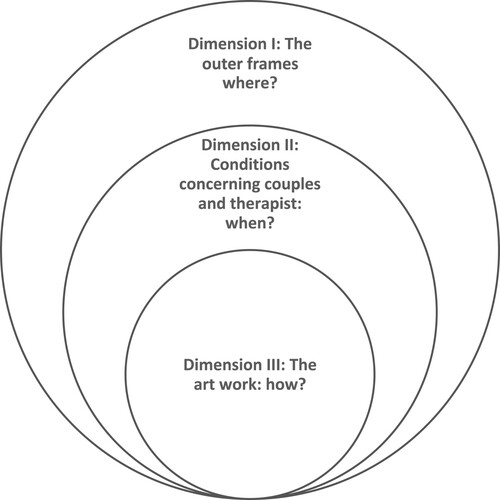

The results showed that, through non-verbal communication, art making facilitated clarification of situations, handling non-talkable concerns, and added playfulness to the relationship. Three crucial dimensions were identified in the family counselling context: (1) outer frames, i.e. room and material; (2) some special conditions, i.e. that they trusted each other and both wanted to repair their relationship, and the therapist’s ability to assess this; and (3) art work techniques that all couples could master.

Conclusions

Art therapy could benefit couples in relational crisis, given appropriate prerequisites were ensured. Implications for practice: suitable rooms and appropriate materials have to be arranged if the social services want to offer couples in relational crisis art therapy as a tool in their work to reduce marital distress and prevent separations.

Plain-language summary

This study explores art therapy used by couples in relational crisis, from the viewpoint of art therapists. Seven art therapists were interviewed. The results showed art therapy could benefit couples in relational crises. Couples could understand each other better and they could get in touch with positive sides of the relationship. Three factors were experienced as important when using art therapy with couples in relational crisis: (1) to have access to an appropriate art therapy room and sufficient art therapy materials, (2) that the persons in the couple wanted to repair their relationship and that they trusted each other, and (3) that art therapists use easy art therapy techniques that all couples could master. Limitations, research recommendations and clinical implications are discussed.

Introduction

The aim of this study was to explore art therapy used by couples in relational crisis, in the context of family counselling in Swedish Social Services. This pilot study focused on the professionals’ perspective. Art therapy has been found to be beneficial when working to strengthen relationships in couples. Several aspects have been emphasised in the literature. For example, art therapy has been found to be beneficial where one of a couple has developed Alzheimer’s disease (Couture et al., Citation2021). In this context, art therapy was found to have positive effects, such as providing pleasure, expressing emotions, assessing relational dynamics, and fostering empathy. Other studies (Hinz, Citation2020; Weeks, Citation2013) have shown that non-verbal communication used in art therapy offers couples opportunities to discover new aspects in their relationship. Creative interventions can also change the dynamics in relationships and offer a new and creative dimension within which to explore their concerns (Metzl, Citation2020). Further, art therapy offers unexpected experiences that could challenge couples’ assumptions of one another (Wadeson, Citation2010). Creating art together also offers a new perspective where a ‘blame-shame’ dynamic could be altered into a curious one (Metzl, Citation2020). In addition, art therapy improves communication skills and facilitates future problem solving for couples (Lin, Citation2015; Sanchez-Cruz, Citation2017). Art therapy can also increase understanding of the patterns and themes within a couple (Ricco, Citation2007).

Art therapy has also been found to be beneficial when working with parenting struggles; art-based parental training enables parents to connect better with their children's experiences and voice more approval of their children (Shamri-Zeevi et al., Citation2019).

Various techniques and models are used in art therapy with couples, e.g. joint paintings (Snir & Wiseman, Citation2010; Weeks, Citation2013) and Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) (Hinz, Citation2020). One important aspect found in art therapy with couples is the spatial dimension, including the visual experience and function of the art therapy room (Fenner, Citation2012; Malchiodi, Citation2007).

Family counselling is a mainstay in Swedish Social Services. It is mandatory for municipalities to provide relational support for couples in need due to a crisis or another urgent relational situation (SFS, Citation2001:453 5§3). The number of couples receiving family counselling is increasing. In 2019, 6 of 1000 people between 18 and 69 years attended family counselling (Myndigheten för familjerätt och föräldraskapsstöd, Citation2021). The aim of couple therapy is primarily to reduce marital distress, and the main tasks for the family counsellor are to (1) help couples find constructive solutions to conflicts, (2) improve their life together, (3) avoid a destructive separation, (4) facilitate joint parenting when couples separate (Lundblad & Hansson, Citation2005a). Family counselling is a low-threshold service financed by taxes and fulfils a basic function in the Swedish welfare system. Regardless of personal financial circumstances, all citizens can attend family counselling. In Sweden, common problems among couples attending family counselling are communication difficulties and stressful life situations (Burman et al., Citation2018).

Family counsellors employed in Swedish Social Services have a high degree of discretion (Lipsky, Citation1980) concerning the therapy methods used (Lundblad & Hansson, Citation2005a). The counsellors can suggest whatever therapy they find appropriate for each couple in crisis that they meet. Empirical studies have shown that even a short and limited treatment can lead to significant improvements in psychiatric symptoms among couples attending family counselling (Lundblad & Hansson, Citation2005b). However, there have been no further studies exploring preferred therapies since the early 2000s. How are the therapies applied? Why are they chosen by the family counsellors? Family counsellors in Swedish Social Services should apply evidence-based methods based on professionals’ experiences, research, and clients’ experiences (Föreningen Sveriges Kommunala Familjerådgivare, Citation2019). Cognitive behavioural therapy is widely used in family counselling, but other evidence-based therapies are also applied, including art therapy. Today, there is a lack of knowledge about the role of art therapy when used with couples in crisis in Swedish municipal family counselling. Why do family counsellors suggest art therapy for couples? How is art therapy conducted in the context of family counselling in Swedish Social Services? This article contributes to these questions. The aim of this study was to explore art therapy used by couples in crisis applied in the context of family counselling in Swedish Social Services. This pilot study focuses on the professionals’ perspective to investigate the following questions: What characterises art therapy with couples in relational crisis in the family counselling context? Why, when, where, and how is it used? When is it not used, and why? From the art therapists’ experience, what does art therapy contribute in the family counselling context?

Methods

Research design

A qualitative study was considered suitable to explore art therapy with couples in relational crisis from a professionals’ perspective (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018). The qualitative research design provided opportunities to scrutinise the professionals’ experiences of using art therapy with couples in relational crises in depth and to identify similarities as well as nuances concerning the research questions posed.

Throughout the study, ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects (World Medical Association, Citation2013) guided the work. The principles of informed consent, voluntary participation, and confidentiality were emphasised throughout the study. This study included professionals’ experiences of using art therapy with couples in relational crises, no ethical application was considered necessary. The informants were not considered to be in vulnerable situations, but participated in the study in their professional roles, with extensive experience of carrying out art therapy with couples in relational crises.

Participants

Informants were recruited to the study by purposive sampling (Polkinghorne, Citation2005), which meant that they could provide relevant experiences in relation to the purpose of the study. The Municipal Swedish Family Counsellors’ Association (KFR) was contacted by phone, and information about recruiting informants for the study was posted on the associations’ website in September 2019. In addition, members in a network of family counsellors with art therapy competence within the association were contacted personally. In total, seven art therapists, employed as family counsellors and working with art therapy in the context of family counselling in Swedish Social Service participated in the study. The informants had used art therapy with couples in relational crises for between 2 and 30 years.

Procedures

Semi-structured interviews took place between October 2019 and January 2020. Each interview lasted for 40–60 min and was recorded and transcribed verbatim (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018). The interviews were carried out by phone as the informants lived in various parts of Sweden. During the interviews, questions concerning informants’ experiences of working with couples in relational crisis were posed:

What guiding theories/models do you use in your work with couples?

Can you tell us how you implement art therapy with couples in practice?

Art therapy interventions?

What problems are couples having?

Do you think art therapy/art interventions may be appropriate? Any advantages/disadvantages of using art therapy with couples?

Data analysis

Thematic analysis with an inductive approach was applied to analyse the data according to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The analytical work consisted of the following six stages. (1) The printed material was read several times to become familiar with the data and the idea ‘let the material speak to you’ was the starting point. The question of whether there were any patterns appearing guided the reading. (2) Initial codes were generated. Different patterns in the material were highlighted and a first mind map was drawn. (3) Themes were identified. The work with various mind maps continued, and the first preliminary themes/sub-themes were found. Statements that were considered to fit the different themes/sub-themes were highlighted. (4) The themes were reviewed and the authors returned to the first three phases. According to the analysis model (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), the analysis is a back-and-forth process in which the researcher moves between the different steps. (5) The themes were defined and named. Eventually, a common thread was discovered in the process, and the main themes/sub-themes were determined. Quotes from the interviews were sorted under each theme. (6) This article was written and the results presented for readers to examine.

Validity/reliability

Triangulation in terms of multiple analyses (Ritchie & Lewis, Citation2003) was used to validate the study. Both authors, with different areas of expertise, were involved in the analysis of the data when codes, themes and sub-themes were identified and reviewed. Validity was also addressed when the preliminary results were presented to the scientific community, critically reviewed and discussed by three external readers within academia. The reliability of the study was addressed by a careful and transparent description of the procedures used and of the material gathered so that others could follow the same procedures and arrive at the same conclusions. Personal perspectives, experiences, and skills among those involved matter when performing a study. However, the findings and conclusions drawn should not diverge fundamentally when repeating the study. Carefully selected quotes are included to strengthen reliability.

Results

The reasons for using art therapy with couples in relational crisis, as expressed by the family counsellors, are explored in relation to the question why? Three dimensions of art therapy identified as crucial in the context of family counselling in Swedish Social Services are presented in relation to the questions where, when, and how?

Reasons for using art therapy with couples in relational crisis: why?

The informants found that art therapy revealed thoughts and feelings that could be difficult to convey in traditional voice-based therapy. Adding art making to the conversation was also experienced as helping individuals to perceive each other beyond thoughts and the spoken word.

What can be very effective in working with couples is that through the painting, they can see each other in a way that you cannot always do with the help of the words. […] The painting is so direct and can also resonate with the other on a deeper level, so you actually get to see each other. And I have experienced that with a couple, we went on for ages and never really got there. Then we tried with art therapy and it was striking; they saw each other and could sort of move on from that. (Interviewee 2)

Art therapy was considered useful to awaken and get in touch with positive aspects of the relationship, to gain new insights and understanding of each other. Informants experienced that art therapy could bring out things that people had not thought of before. The reason for that was explained in terms of art therapy offering both verbal and non-verbal communication. Thus, an additional type of communication was experienced in art therapy compared with verbal therapy, which only offered verbal communication.

For example, in a painting, the messy room emerges. They showed me the dirty room, they had painted it in black. […] The ability did not exist to put it into words, because painting is a different way of communicating than talking. (Interviewee 1)

Most of the informants thought that art therapy worked particularly well with people who had difficulty expressing themselves verbally. However, one art therapist believed that those who had problems expressing themselves verbally also had difficulties expressing themselves in paintings. Informants also emphasised that art therapy worked well with couples where one of the couple was less verbal, and with people who talked too much.

You can get rid of this, what we could call ‘the therapy talk’, and instead get to the bottom or core. (Interviewee 6)

Three crucial dimensions of art therapy in the context of family counselling for couples in relational crisis

In the interviews, the following three dimensions were identified () as characterising art therapy work with couples in relational crisis in the context of family counselling: (1) the outer frames (rooms and materials), relating to the question where; (2) conditions concerning the couple and the therapist, relating to the question when; and (3) practical art work, relating to the question how?

Dimension I: the outer frames: where?

A room and the materials are a prerequisite for art therapy. Some informants had specific art rooms where the couples could paint. Sometimes rooms were arranged so that the individuals in the couple could choose whether they wanted to stand up or sit down and paint. Other therapists re-furnished their therapy rooms into art rooms. They placed screens where couples could put up paintings in the room. Because the couples had not explicitly sought an art therapist, the art therapists used the room and the materials to arouse curiosity about the method:

Because they were not looking for me as an art therapist, they first saw that I had crayons, paper, brushes, and paints. They became curious about the paints and brushes, and some could back off. I would then say: Shall we try? Try it once or twice and you will get a feeling for what it is like. I told them that this is another way of working with another language. (Interviewer 3)

It was often watercolors and acrylics. These were ordinary crayons. And pastel crayons and many different brushes. So that they could express themselves in many different ways. And then I made sure that I had a large roll of paper that I cut from, also according to what they themselves wanted and taped up on the wall. Some wanted to stand and paint. Others wanted to sit with the crayons. I thought people should be able to choose what they are used to. (Interviewee 6)

Other therapists preferred to narrow the choice of material to make it easier for the couples.

Always acrylic. Acrylic is easy. It dries well. (Interviewee 1)

Dimension II: conditions concerning couples and therapists: when?

According to the informants, the following two basic conditions needed to be in place for art therapy to be appropriate for a couple; that they both wanted to repair their relationship and that they trusted each other.

There must be basic trust when working with art and couples. They should feel safe and trust each other; and that what you say will not be abused, but you say it in order to build the relationship further and especially to help them find joy together again. (Interviewee 2)

What happens when you are in crisis and your whole life sways […] man's worst side wakes up. You also become so defensive. And there you should definitely not use art therapy, I feel. Because art therapy is such a powerful tool, and you go a little behind the censorship. […] You should not open up more than can be taken care of. (Interviewee 2)

Dimension III: the art work: how?

The informants worked using the following directive and theme-based therapeutic interventions:

Painting themselves as individuals and their relationship: couples were asked to paint pictures of how they imagined their relationship in the future (Interviewees 4 and 5). Couples were given the task of painting themselves in relation to the other (Interviewees 1 and 3).

Painting together in collaborative exercises: couples did joint collaborative paintings where one first painted a line, and the other responded by continuing to paint further from the line (Interviewees 1, 3, and 4).

Painting metaphors: couples were asked to paint metaphors that the art therapist suggested (Interviewees 1, 3, and 4). Couples were asked to paint a house or a tree and then reflect together on the pictures (Interviewee 7). Couples were asked to paint a ‘wish house’ or a ‘wish tree’ to express how they wanted the future to be (Interviewee 7). Couples were asked to paint themselves as a flower or animal to express themselves on a symbolic level. The couple then had the opportunity to reflect on the painted flowers, such as reflections on the properties of the specific flowers and how they matched each other (Interviewees 2, 3, and 6).

In one example of how one of the techniques was beneficial, the couple had painted themselves as animals. By using the paintings, the individuals could reflect on the balance in their relationship:

I remember a couple where the woman made herself like a sea lion. The man, he was probably a little cat or a dog, some small animal. And it became so clear how big she was and how she took a lot of space. […] In such a picture, we talked about how these animals could get along, how these animals could meet or take care of each other. (Interviewer 3)

I often let them try first and play down the art making by asking them to describe who they are by letting them choose colors, shapes that they somehow think remind them of themselves, because they say ‘I can’t paint’ and ‘I can’t draw’. Often there is so much prestige, and you need to tone this down with some kind of playfulness in the materials. I use a lot of tissue paper, tear and paint with tissue paper and wallpaper paste, for example, and it is something that many people start with and then they move on from the difficult idea that they need to perform. (Interviewee 4)

The informants emphasised that the art materials could lead couples on to a thought or insight of some kind or put them in a certain mood. The material was an important part of the therapy; it had a therapeutic function. Crayons were considered to be a good material for anger, and liquid colours were considered useful for those who needed to let go of control. One informant had experienced how a couple got tools to manage their relationship by using different materials, fluid colours and clay, in the same painting:

The woman makes herself in profile facing the man's picture and then she takes out plastic clay and then she sculpts an ear, a big ear and then she asks, may I do something in your picture? Yes, he says, you can. And then she takes that big ear and puts it on his figure that he has done. And this is going to be a lot of fun, because she thought; he says he listens, but he never hears anything. So she put a big ear on him so he could hear a little better. It was both fun, but it also became so concrete and clear to him what it was like. (Interviewee 4)

The informants emphasised the importance of asking Socratic questions, i.e. that couples themselves needed to find insights, understanding and solutions. Examples of Socratic questions that the informants asked were: What do you see in the picture? How did it feel to paint? What did you think? Is there something in the picture that makes you feel or think that way? What do you think that figure means?

In some cases, art therapists used techniques that included people other than the couple themselves. One informant conducted art therapy with the couple's children, and then let the couples look at the children's drawings; they could then see how their conflict affected them.

We always talked about having the opportunity to talk to the children when there were very difficult conflicts. Several parents brought their children there. And it is very easy for children to paint; it is usually their way of expression. Sometimes they could tell a fairy tale or so, and it was quite fascinating because all the children who painted wanted the parents to come in and look, and there was a lot of emotions then, because the parents saw how the children struggled with the conflict they had. (Interviewee 7)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore art therapy with couples in relational crisis from the professionals’ perspective. The research questions concerned what characterises art therapy with couples in the context of family counselling? When, where, how, and why was it used? When was it not used, and why? What did art therapists experience that art therapy contributed to family counselling?

The results showed that art therapy contributed to counselling with couples in relational crises by providing a playful method where couples could look at each other in new ways. They were given the opportunity to see the world through the others’ eyes, a common need expressed by couples in couple therapy (Malchiodi, Citation2011). When making art, couples could bring out things that they had not thought of before. Art making further facilitated couples to identify the core of a problem. According to the informants, art therapy added vital dimensions to the couple's opportunities in their work with their relationships. These results are in line with previous research showing that art therapy can strengthen couples’ relationships in various ways (Hinz, Citation2020; Metzl, Citation2020; Weeks, Citation2013). For couples who needed to bring more positive elements into their relationship, art therapy enabled this by its playfulness. According to Case and Dalley (Citation2014), the essence of art therapy lies in creating something. Art therapists can create a space within which adults in therapy can play. Art materials can be used as a catalyst for play, and in playing one can surprise oneself as an image emerges. Playfulness was a dimension emphasised by the informants in the present study.

The techniques described by the informants could all be identified as appropriate to use when addressing specific aspects of relationship work according to previous research exploring art therapy with couples in other contexts. Techniques were used that could help couples talk about the pictures, for example, in metaphorical ways, instead of talking directly about themselves in line with previous research (Kerr et al., Citation2008). The technique of painting together in collaborative exercises also addressed communication skills. In Sweden, communication problems are one of the main reasons why couples seek therapy (Burman et al., Citation2018). Art therapy research shows that art making is a useful tool to apply when aiming to develop communication skills (Sanchez-Cruz, Citation2017). Accordingly, on the basis of this study, specific art therapy techniques were experienced to facilitate development of communication skills in couples in relational crisis. One final reflection on the techniques used concerns individuals’ painting skills. Informants used instructions to paint motifs such as a flower, an animal, a tree or a house. In previous research, it is not known if art instructions in the form of metaphors were used when working with couples. Based on studies of children's development in painting (Forsberg, Citation1993), from early scribbling to paintings of motifs, it could be suggested that art therapists working with couples in relational crises chose to suggest things that children could paint from the age of 3–4 years, including flowers, animals, houses, and trees. Questions rising are whether the choice of motifs show that art therapists gave instructions on motifs that individuals in all couples could master, regardless of previous experience of art or art-making skills? Did the use of early art-making skills (at 3–4 years) contribute to couples coming in contact with their own playfulness? Additionally, could this even be about psychological methods such as the House Tree Person Test (Frankish, Citation2016) which holds that visual patterns can give clues to a person`s relationships with others and the image they have of themselves? These are questions that need to be further investigated.

Limitations

One limitation concerns the number of informants. It was difficult to find family counsellors who were also art therapists. Despite the limited number of informants, their vast experience (from 2 to 30 years) working with art therapy with couples in relational crisis was assessed as sufficiently extensive to answer the research questions.

Another limitation is of a more profound character. This pilot study is limited to professionals’ perspectives. Since the results from this study were based only on professionals’ experiences, there is a risk of potential practitioner bias. To avoid bias, professionals’ perspectives could have been triangulated with clients’ experiences. Previous research shows that client knowledge does not necessarily correspond with clinical knowledge, and the occurrence of epistemic injustice, in among other also the Swedish welfare services (Grim, Citation2019), suggests that clients’ experiences always should be a source of knowledge providing client knowledge in contrast, or in line with clinical knowledge. The reason why a participants’ perspective was not included in this pilot study, was that the authors considered involvement of participants, situated in stressful relationships and vulnerable situations, were not ethically correct in this very first stage of exploring the field. Our intention was to search for initial knowledge, including whether art therapy in this context was even assessed as appropriate to apply or not.

The authors’ understanding of the evidence is in line with the definition of the concept made by Rycroft-Malone et al. (Citation2004), where evidence include (i) research, (ii) clinical experience, (iii) patient experience and (iiii) information from the local context. Thus, based on the results of this pilot study, suggesting art therapy could benefit couples in relational crisis, a subsequent study have been designed and planned for. In this study (iii) couples’ experiences will be captured both qualitatively and quantitatively. In a first stage a feasibility study will be conducted. A manual-based phenomenological art therapy intervention, developed and evaluated in the Swedish welfare context (Blomdahl et al., Citation2018) will be adapted to the family counselling context. In this process (iii) couples’ experiences will be of outmost importance. Information from (iiii) the local context will also be a source of knowledge. Following the feasibility study, an RCT, referred to as (i) research, is also planned for, where ‘satisfaction with relationship’ will be the primary outcome measured. The pilot study is limited to address (ii) clinical experience. However, the study as a whole will address all dimensions of evidence as described by Rycroft-Malone et al. (Citation2004). The authors’ long-term intention is to contribute with an in-deepth and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon that could benefit the research field of art therapy with couples, as well as family counselling practitioners expected to prioritise and apply evidence-based methods.

Practical implications

Counsellors in the organisation had discretion (Lipsky, Citation1980) about the therapy, which meant they could use art therapy when they thought it was appropriate. However, the outer frames needed to be in place to be able to carry out the art therapy. The spatial dimension has been identified as an important aspect in art therapy with couples; including the visual experience and function of the art therapy room (Fenner, Citation2012; Malchiodi, Citation2007). This implies that suitable rooms and appropriate materials have to be arranged if the social services want to offer couples in relational crisis art therapy as a tool in their work to reduce marital distress and prevent separations (Lundblad & Hansson, Citation2005a). The techniques used, such as common paintings, need space.

Conclusions

In line with previous research on art therapy with couples, our results showed that art therapy was a useful tool when working with couples in relational crisis. Non-verbal communication could help to handle things that were hard to put into words, painting could help couples to come to the core of a situation, painting could provide playfulness in the couple’s relationship, etc. One unique finding in research on art therapy with couples in relational crisis, however, was that art therapy was not experienced as appropriate at all times. Art therapy could be used with couples in a relational crisis when the couple had a wish to repair their relationship and trusted each other. However, art therapy was not experienced as appropriate with couples in a separation process. Another unique finding that could be considered as our contribution to the wider research field of art therapy with couples was the finding that counsellors working with couples in relational crisis used motifs such as a flower, an animal, a tree or a house. These instructions could be related to children's development in paintings from early scribbling at the age of 3–4 years. Individuals in all couples could master these motifs, regardless of previous experience of art or art-making skills. Another understanding of the choice of motifs could be related to the use of psychological methods, such as the House Tree Person Test (Frankish, Citation2016), which holds that visual patterns can give clues to a person`s relationships with others, and the image they have of themselves.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Fjellfeldt

Maria Fjellfeldt is a Researcher and Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Dalarna University, Sweden. She has a PhD in Social Work, and she has been awarded the Degree of Master of Art Therapy in 2007, at Umeå University, Sweden. As an Art Therapist, she is interested in using visual methods in her research context. Prior to her doctoral studies, she worked as a Social Worker and Art Therapist for ten years.

Dalida Rokka

Dalida Rokka is lic. Medical Social Worker, lic. Psychotherapist educated and trained Supervisor in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, and has the Degree of Master of Medical Science in Art Therapy. Since 2019 she works in municipal family counselling in Mora, Sweden, with couples therapies and domestic violence. In her work as a family counsellor she applies art therapy and other creative techniques, such as mental imagery, clinical hypnosis and mindfulness-based cognitive art therapy.

References

- Blomdahl, C., Guregård, S., Rusner, M., & Wijk, H. (2018). A manual-based phenomenological art therapy for individuals diagnosed with moderate to severe depression (PATd): A randomized controlled study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(3), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000300

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208963

- Burman, M., Norlander, A.-K., Carlbring, P., & Andersson, G. (2018). Närmare varandra: 9 veckor till en starkare parrelation [Closer to each other: 9 weeks to a stronger couple relationship]. Natur och Kultur.

- Case, C., & Dalley, T. (2014). The handbook of art therapy. Routledge.

- Couture, N., Villeneuve, P., & Éthier, S. (2021). Five functions of art therapy supporting couples affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Art Therapy, 38(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2020.1726707

- Fenner, P. (2012). What do we see? Extending understanding of visual experience in the art therapy encounter. Art Therapy, 29(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.648075

- Forsberg, L. (1993). Det bildterapeutiska rummet [The art therapeutical room] Arbetsenheten för psykoterapiutbildning [Unit for psychotherapy education]. Umeå University.

- Föreningen Sveriges Kommunala Familjerådgivare [Association of Swedish Municipal Family Counselors]. (2019). Policy document om kommunal familjerådgivning [Policy document on municipal family counselling]. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://www.kfr.nu/kvalitetskrav/kompetens-och-kvalitet-inom-familjeradgivningen/kfrs-policydokument/

- Frankish, P. (2016). Disability psychtherapy. An innovative approach to trauma-informed care. Karnac.

- Grim, K. (2019). Legitimizing the knowledge of mental health service users in shared decision making: Promoting participation through a web-based decision support tool. Dalarna University.

- Hinz, L. (2020). Expressive therapies continuum. A framework for using art in therapy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429299339

- Kerr, C., Hoshino, J., Sutherland, J., Parashak, T. S., & McCarley, L. L. (2008). Family art therapy: Foundations of theory and practice. Routledge.

- Lin, L.-Y. (2015). Art therapy to improve communication skills for Chinese premarital couples [Master’s thesis, Department of Counseling and Mental Health Professions, Hofstra University]. ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/openview/f8262171da498a698d4ec8e0c7c9f433/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.2307/1288305

- Lundblad, A.-M., & Hansson, K. (2005a). Relational problems and psychiatric symptoms in couple therapy. International Journal of Social Welfare, 14(4), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-6866.2005.00368.x

- Lundblad, A., & Hansson, K. (2005b). Outcomes in couple therapy: Reduced psychiatric symptoms and improved sense of coherence. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 59(5), 374. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480500319795

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2007). The art therapy sourcebook. McGraw-Hill.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2011). Handbook of art therapy. Guilford Publications.

- Metzl, E. (2020). Art therapy with couples: Integrating art therapy practices with sex therapy and emotionally focused therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(3), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2020.1774628

- Myndigheten för familjerätt och föräldraskapsstöd. (2021). [The agency for family law and parental support]. www.mfof.se

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

- Ricco, D. L. (2007). Evaluating the use of art therapy with couples in counseling. A qualitative and quantitative approach [In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Art Education, Florida State University].

- Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage.

- Rycroft-Malone, J., Seers, K., Titchen, A., Harvey, G., Kitson, A., & McCormack, B. (2004). What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03068.x

- Sanchez-Cruz, C. (2017). Improving communication in couples through art therapy [Masters of Art thesis in Marital and Family Therapy. Notre Dame de Namur University]. ProQuest LLC.

- SFS (Swedish Code of Statutes). (2001:453). Socialtjänstlag [Swedish Social Service Act]. Socialdepartementet.

- Shamri-Zeevi, L., Regev, D., & Snir, S. (2019). Art-based parental training (ABPT) – parents’ experiences. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(4), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1641117

- Snir, S., & Wiseman, H. (2010). Attachment in romantic couples and perceptions of a joint drawing session. Family Journal, 18(2), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480710364318

- Wadeson, H. (2010). Art psychotherapy. John Wiley.

- Weeks, G. R. (2013). Treating couples: The intersystem model of the Marriage Council of Philadelphia. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203776575

- World Medical Association. (2013). WMA declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.