ABSTRACT

Background:

In light of recent research and a growing understanding of the destructive repercussions of secrecy and concealment, unique interventions are required.

Aims:

This article, part of an art-based qualitative-phenomenological study, explores the subjective experiences of adults who grew up under secrecy.

Methods:

The research utilised art therapy, readymade art, the creation of stories and interviews. These allowed access to primal, non-verbal and unconscious aspects of the experience and to implicit and explicit memories and their impact.

Results:

The study revealed themes of connection, disconnection and integration, reflecting recurring aspects of participants’ artworks, and prominent narratives in their stories and interviews. The intermodal transfer between art forms valuable while enriching and expanding the content of the art-based session.

Conclusions:

Participants’ experiences revealed an inability to connect between information kept secret during childhood and information that was not. They experienced ambiguity and a sense of something missing in relation to information that was sensed but could not be conceived.

Implications for practice:

This article offers clinical implications relating to art-based psychotherapeutic work with clients who grew up under secrecy. The process uses metaphors emerged from visual and narrative expressions. A possible application is related to the intermodal transfer between art forms enriching core themes in a way that enables clinical work using metaphors produced by the participants. A possible implication is the clinical use of arts-based intervention inviting clients to create a variety of metaphors from the ready-made artwork and from their stories, which in turn expand the outlook upon the experience, enabling access to its implicit components.

Plain-language summary

Research has shown that growing up in an environment of secrecy and concealment can be harmful. New knowledge in this field can contribute to the development of unique interventions designed to assist clients who are coping with psychological damage of this kind. This study explored the experiences of 11 adults who grew up in the shadow of a secret. During an individual, 90-minute session with the researcher, each participant was invited to engage in readymade art, i.e. create a visual artwork from everyday objects provided to them. Following this task, each participant observed his or her work together with the researcher and was then asked to compose a story or dramatic monologue based on the artwork. In the last phase of this 90-minute session, the participants were interviewed.

Findings of the study reveal that themes of connection, disconnection and integration repeatedly appear across the artworks, narratives and interviews. The transition between the various modes – artwork, dramatic monologue and interview – enabled the emergence of rich content and images. The discussion explores the experience of participants who grew up in the shadow of a secret, and especially their feelings of ambiguity and sense of something missing, as well as their inability to connect the fragments of information they encountered and build an integrative narrative of their lives.

Introduction

What is a secret? Confidentiality is defined as the intention of keeping information known to one person secret from one or more other people (Slepian, Citation2022). In fact, any real or imaginary object, thought, event or emotion can become a secret, as long as it is hidden from the consciousness of the other (Wismeijer, Citation2011). The act of concealing a secret is a conscious one that requires mental effort (Bouman, Citation2003; Frijns, Citation2004; Hillix et al., Citation1979; Margolis, Citation1966; Lane & Wegner, Citation1995). Keeping a secret exacts a psychological and physiological toll, and may undermine the sense of genuineness, damage self-worth and subjective well-being, and cause stress (Slepian et al., Citation2017). In addition, people who conceal a secret are more likely to suffer from depression (Constantine et al., Citation2004), social anxiety (Rodebaugh, Citation2009) and difficulties in self-regulation (Critcher & Ferguson, Citation2014). Slepian and his fellow researchers reached the innovative conclusion that these symptoms are not the result of the ‘weight’ of the secret or its severity, but rather the frequent mind-wandering associated with it (Slepian et al., Citation2017), or, in other words, to what extent the person comes in contact with the secret.

Coping mentally with secrets and connections

Studies indicate that adults who had significant secrets hidden from them as children cope with painful challenges and the negative consequences of these actions. For example, studies on delayed adoption disclosure indicate distress and lower life satisfaction (Baden et al., Citation2019). A qualitative study that examined the experiences of adults whose parent's suicide was hidden from them in childhood cited experiences of fragmented and partial information, difficulties in family communication and the belief that, for the family’s sake, it is better to keep the true circumstances of the parent's death a secret (Ratnarajah & Schofield, Citation2008). In another study, (Wilson et al., Citation2022), adults whose parent died by suicide described they experienced the concealment, half-truths and avoidance of the subject altogether as detrimental. Studies that examined the experience of adults who were not told that they were born from a sperm donation also reveal severe loss of trust in relatives, despondency, numbness, confusion and shock (Frith et al., Citation2018; Riley, Citation2013).

A parent’s tendency to hide painful, shameful or embarrassing past events from their children often stems from a desire to protect them (Draznin, Citation2018). Secrets greatly impact relationships in the family; according to Imber-Black (Citation2019), they are a kind of magnet that attracts and pulls family members who know the secret close, while distancing those who do not. Thus, a complex network of relationships is created: some of these relationships allow intimacy while others are characterised by conflict, alienation and disengagement. Mazor (Citation2017) explains that family members who are not aware of the secret are exposed to psychological states and references that provide only partial information. Children can experience these gaps in information as threatening feelings, when what is known gets mixed up with what is hidden and explicitly forbidden. The familiar becomes menacing and the domestic becomes unheimlich, Freud’s term for this merging of familiar with threat and danger (Freud, Citation1990). Mazor (Citation2017) asserts that when pieces of information do not come together to form a coherent and meaningful whole, the result is fragmentation in which each person remains isolated in their subjective experience and disconnected. In extreme cases, profoundly different perspectives stemming from situations of secrecy and concealment can create divides and ruptures in family relationships (Mazor, Citation2017). In her view, individual points of view also disintegrate, creating a lack of cohesion in the shared family space as well as in the individual's interpersonal and intrapsychic narrative experience. Bollas (Citation2017) termed unschematized knowledge – those early, self-evident, nameless feelings that are an inseparable part of the self – unknown thoughts, i.e. they cannot be processed, as they have not come to light. This study uses the language of art therapy, which enables the investigation of primary, infantile and pre-verbal experiences, to access these specific kinds of memory.

Connections and rupture in arts therapy

Arts therapy makes use of sensorimotor and motor functions that enable access to non-verbal images and emotions (Lusebrink, Citation2004). The use of physical, auditory and visual expressions in the various arts results in the integration of implicit, non-verbal memories stored in the right hemisphere of the brain and explicit, verbal memories stored in the left hemisphere (Dominie, Citation2020; Hass-Cohen & Findlay, Citation2019; Klorer, Citation2005; Lusebrink, Citation2014; Malik, Citation2022; Sarid & Huss, Citation2010; Talwar, Citation2007). Thus, the artist’s efforts to connect different art materials, structures and images – for instance when creating a collage, a clay sculpture or a woodwork item – reflect the attempt to establish connections between various mental images or content that are difficult to process (Bat Or & Megides, Citation2016), and often associated with loss (Strouse, Citation2014) and/or close relationships (e.g. Bat Or & Zusman-Bloch, Citation2022).

Orbach (Citation2019), who explores the emotional and cognitive meanings of materials chosen in the creative process and the power of these materials to lead to dormant memories and obscure parts of the mind, claims that the selection process is a physical experience that cannot be conceptualised in most cases, but involves communication of the body with objects, materials and objects. The artist’s choices later, it later turns out, are not accidental and very significant. Orbach (Citation2019) defines a category of materials that she calls ‘connectors, separators, and measurers;’ which serve to mediate between body and material, and can create closeness or distance, attachment, or separation. The current discussion will focus on two specific ‘connectors’ relevant to the study’s findings: glue and string. Metaphorically speaking, glue can repair and treat a mental crack. The use of glue may reflect a desire to connect elements, but also the possibility of disintegration, when the glue doesn’t work. The glue itself can be clear or represent various degrees of opacity, which makes it suitable material, according to Blumenfeld and Kadosh (Citation2017), when dealing with themes of concealment and visibility. The use of glue can indicate a desire to create an integrative environment and continuity. In reference to the ‘glue’ of relationships, we will use the term ‘adhesive identification’ coined by Bick (Citation1968) and later expanded by Meltzer (Citation1975) describing a primitive attachment pattern with a significant other. This type of identification, as opposed to mature identification processes, is characterised by identification with external characteristics on the other’s surface. The internalization process involves not internal content of the other, but mimicry, adhesion or adherence to superficial characteristics, especially those that are visible to the eye. Adhesion to these external characteristics prevents the sense of internal disintegration.

Yarn, thread, cords etc., can potentially serve to explore issues of rupture and connection. These are all a combination of plant, animal or synthetic fibers that are used in knitting, weaving, sewing making rope, and other crafts. According to Arbel (Citation2014), various fiber or other crafts enable access to unconscious and/or unspoken content. Raw fibers represent the potential for transformation and realization. The transformation of yarn into a knitted object is like a journey. She claims that textile arts contain an element of apprenticeship as they are passed on from generation to generation. Winnicott (Citation1971) in his discussions of objects of transition, emphasises the connecting qualities of string, which packages and holds things together. String enables the expansion of all other modes of communication and as such can be associated with lack of communication. The various aspects of these connectors, and their dominance in the artworks of the participants, will be described in detail in the findings and discussion sections below. Albeit further study is needed, this article offers a suggested arts-based intervention which might be relevant to clinical processes for art therapists as well as therapists from other fields dealing with secrets and concealment.

Methods

Study design

This study utilises the descriptive phenomenological psychological method (Giorgi & Giorgi, Citation2003) together with an art-based phenomenological research methodology (Betensky, Citation1995; Kapitan, Citation2018). This research methodology includes a systematic observation of participants’ associations, interpretations, and visual expressions. The main aim of a phenomenological analysis of this kind is to observe participants’ meaning making processes (Smith et al., Citation2022); i.e. how they make sense of their subjective experiences.

The first part of this study used tools from the field of visual art and drama; participants were invited to create a visual artwork with readymade materials and found objects. Following this, we used the concept of intermodal transfer (Knill et al., Citation2005) drawn from the field of expressive arts therapy, and asked participants to compose a story or dramatic monologue based on their artwork. The transition from one art medium to another facilitates and refines the exploration and provides the opportunity to ‘deepen and further expand on the client’s emerging themes’ (Ram-Vlasov & Orkibi, Citation2021, p. 3). Every one of these sessions was conducted by the first author.

Measurements and/or materials

Identical materials were provided to the participants and included a wide range of everyday items that could be used to represent their experiences, such as kitchenware, utensils, garden tools, jewellery, various electronic devices, children’s toys, eyewear etc. These items were all donated by people responding to an advertisement calling for ‘junk’ and otherwise useless objects. This was done in order to allow creating with recycled and dual-usage materials out of an ecological outlook. The researchers did not choose the materials personally but did present them to the participants assorted into different baskets by categories (jewellery, kitchenware etc.).

Intervention description

One meeting with each participant was conducted in his or her home. These 90-minute meetings were comprised of three parts: creating the artwork; the drama exercise and an in-depth, semi-structured interview.

The artwork: The participant was provided the above-mentioned materials along with additional means for connecting and cutting, such as glues, threads and scissors, and invited to create a visual artwork depicting his or her childhood experience in regard to the question: How did it feel to grow up in the shadow of a secret? Readymade materials have been found to facilitate the non-verbal encounter with painful and incoherent fragments (Bat Or & Megides, Citation2016) in art therapy interventions. When the participant finished, the researcher took a photograph of the outcome on a white background. Participants were asked to name their artwork.

Drama exercise. We asked participants to compose a story based on their artwork; they could invent a specific persona or omnipotent narrator or narrate in first person. The stories were recorded and later transcribed.

Semi-structured interviews. First, we conducted a joint phenomenological observation (Betensky, Citation1995) of the artwork and processed the drama exercise. This gave participants a chance to articulate implicit images that emerged from the process. Interviews were based on pre-formulated questions but allowed for in-depth inquiry pursuant to the interviewee’s answers (Creswell, Citation2014). The goal of this stage was to better understand the impact and meaning of the subjective experiences of the participants. The interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

Data analysis

The present study integrates, triangulates, crystallizes, and analyses data (Janesick, Citation2000) from participants’ visual art outcomes; stories told about the artwork; and semi-structured interviews. It is based on the phenomenological and qualitative paradigm (Moustakas, Citation1994; Neubauer et al., Citation2022) and on verbal and non-verbal representations stemming from the creative processes and verbal narratives. The analysis was conducted using the photo of the artwork. Phenomenological analysis enables a better understanding of the unique phenomena that is being studied and ensures depth and multiperspectivity (Larkin et al., Citation2019).

We analyzed the photos of the visual artworks using the phenomenological approach (Betensky, Citation1995; Kapitan, Citation2018), while identifying visual elements relating to form and content, such as the frequent use of a specific material or item; gluing methods; layers concealing objects; and more. Data analysis was carried out according to the descriptive phenomenological method (Giorgi & Giorgi, Citation2003), and broadened according to two of Creswell’s (Citation2013) recommendations. After familiarising ourselves with the data, it was coded phenomenologically into meaning units. In the next step, we identified psychological meanings related to participants’ experiences and the nature of the phenomenon under study. We then did a qualitative synthesis of these units to determine higher order categories, subthemes and themes, using reflexivity as one of our tools. In the next stage of the process, we created a consolidated narrative of the psychological structure of the experience. Finally, based on Creswell’s (Citation2013) ‘imaginal variation,’ we re-read the final description to test the themes’ essentialness; finally, we ‘synthesised meanings,’ i.e. identified the most essential meaning of a phenomenon, and searched the data for vivid exemplifications.

The lead researcher collected and analyzed the data with special attention to subjective bias. The systematic and reflective documentation of insights and experiences allowed for the smooth and accurate tracking of transitions from raw data to conceptualization (Birks et al., Citation2008), and sensitivity to the researcher's own reflective voice. The researchers’ professional background is pertinent: the first author is a drama therapist and psychodynamic-oriented psychotherapist who works in a mental health clinic for children and youth. The second author is an art therapist and psychodynamic-oriented psychotherapist, as well as a lecturer at the School of Creative Art Therapies at Haifa University. One focus of the second author’s research is readymade artworks dealing with trauma and loss. She was also involved in reviewing the phenomenological reduction and the final report in order to achieve ‘intersubjective validity’ (Moustakas, Citation1994). In other words, the findings were tested and refined through collaborative analysis.

Participants

The study participants were eleven adults (6 women and 5 men, ages 23–71, average age 42.7) who responded to an ad published in Hebrew and Arabic, inviting adults who had a secret hidden from them during childhood to share their experience through a process involving creative medias and an interview. The participants were individually invited to a single session, which was not part of therapy or clinical intervention as was pointed out to them. The ad noted that participation required no prior knowledge of art or artistic talent. The heterogenic sample included religious and secular Jews as well as Arabs.

Ethical aspects

The focus of this study was adults who grew up in the shadow of a secret: the participants were not required to examine the secret itself, but rather its impact. If participants chose to elaborate regarding the nature of the secret, personal details were altered to maintain confidentiality. In all cases, pseudonyms were used; session outcomes are presented here after obtaining consent to publicise any and all relevant materials. Moreover, it was made clear to participants that they were free to leave the study at any time. Finally, each participant was provided the researcher’s contact details and phone numbers for therapeutic support services and was encouraged to make use of them if they felt the need to share or needed support. The researcher also contacted all participants a week after they participated in the study to check up on them and see if they needed a referral or additional assistance. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Haifa’s Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, approval number 223/20.

Results

This chapter will focus on the recurrent meta-themes of ruptures and connections, which appeared again and again in the three channels of expression: visual artwork, dramatic narrative and interviews. The many explicit and implicit expressions of this theme enrich our knowledge of the experience of growing up in the shadow of a secret and the meaning of this childhood experience to these adults.

Artwork

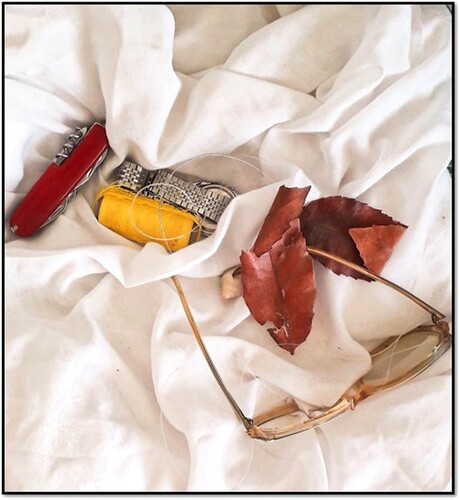

A phenomenological observation of the participants’ artwork reveals that the objects are placed in a way that they can be easily dismantled and leave no trace on the substrate. None of the participants used glue to connect the various objects to each other or to the substrate. The artwork can be divided between those in which there is almost no contact between the objects (5 artworks) and those in which there is contact and even a structure created from this contact (six artworks Sela & Bat Or, Citation2022). In Rami’s artwork, for example, there is no contact between the objects. Rami, aged 52, was not told by his parents that he was adopted. See .

On the other hand, the objects in the artwork of Hanna, aged 70, are touching and therefore form a structure. Hanna was not told the circumstances relating to her aunt’s death in World War II. See .

Surprisingly, despite the fact that participants chose not to use glue to connect objects, five (about half) chose to display glue as a prominent object in the artwork, giving it a new role. Yasmin, aged 42, who was not told a secret about her parent’s extramarital affair as a child, included glue in the mass of objects featured in her artwork but does actually use it to connect objects. See .

In addition to the glue, five of the artworks demonstrate the use of another connecting material: different threads and strings (yarn, embroidery threads, fishing line). The threads in most cases, similar to glue, were displayed and not used for weaving, tying or connecting.

The artwork of Ofer, aged 38, the grandson of Holocaust survivors, who was not told an intergenerational secret related to his family during the Second World War, displays two threads (fishing and embroidery thread) that are not used to connect anything. The piece also features a pocketknife, that is a a cutting tool, that stands in sharp contrast to the connecting materials. See . Jacob’s artwork also features a connector (glue) with a cutting tool (scissors). See .

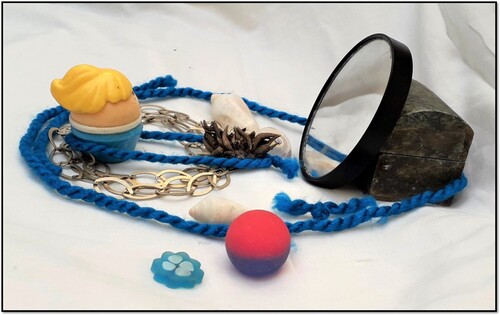

The artwork of Suha, aged 23, whose aunt's suicide was hidden from her, is unusual. The yarn that Suha uses connects objects and also delineates the inner and outer lines of the space. Yarn is the only soft object in the artwork; the other objects are made from metal, wood, and plastic. This two-dimensional use of thread for defining or separating spaces, and not for connecting and tying, recurs in two additional artworks. See .

Stories

Themes pertaining to connection appeared in about half (six) of the participants’ stories. These include pasting, weaving, collecting, repairing and attaching. Some of these stories reflect preoccupation with the desire to know the truth, together with the understanding that knowledge brings pain. Rami’s short, haiku-like story The Secret is one example.

Once upon a time there was an old man who, over time, searched for things

to tell, so it wouldn’t pain him,

and to paste his family together.

There once was a colorful world that was filled with a lot of dirt and filth and pain. Then it self-destructed. And when everything was almost completely hopeless, a kind of force arrived, a force that had been there all along, and watched from the side, and a bit like you cradle a baby, it simply laid itself gently on all the fragments, and said: Everything is fine, and it's fine that things are as they are, and there is order in the world. And it healed by virtue of compassion. As it was joining the pieces together, just before it closed the last seam, it left a gift in the heart of the world, so that the world would remember it and the connection I have to it – to this power.

Interviews

Associations to connections, disconnections and integration came up in the interviews of the research participants, with the exception of one. These narratives reveal a continuum representing, at one end, the desire to confront the hidden secret and ‘paste’ it so that the secret becomes an integral part of a coherent life story, and at the other, an opposite wish to ‘disconnect’ or ‘cut off’ the secret from the life story. Interestingly, among two participants, the theme of disconnection was associated with suffocation, as there is danger in knowledge, and there is also a threat that thread can serve not only for connecting but also for binding and tying. In addition, participants express painful feelings related to mourning for what they did not know as children, and how this lack of connection affected them throughout their lives. For example, Jakov, whose was not told about his grandmother's suicide, says:

‘I felt that some of my roots were cut off, and I'm trying to stick them back. And sometimes I deliberated a lot about even wanting to stick them back on. Like, it's a black subject in my life … it's a part of me, it's part of my image. I want to stick it back on, so that it’s a part of me. Yes, it's important.’

It also makes me suspicious. I suddenly started to suspect all kinds of things, which I don't know are true, even today. I mean … it shook me a lot in relation to myself, regarding my roots, who I am, what I am …

Suddenly I am standing where my parents and grandparents stood. And I am a father, I have to think now how I pass it on – if at all, and if so, when and how – that's the question. I understand that life is more complex than I thought.

There were – there were things that I felt, and I wouldn't have known how to give them any meaning or even organise them in a certain way like now, when I, like, have the answer. So I can build the equation, take from here and there, and make a story out of it. I don't know if this story is accurate.

This knife is closed. A closed knife doesn’t cut, the question is what do you do with it. It’s a tool that has not been used yet. The question is – this is always a dilemma regarding these memories – how much I cut from them and assemble something new and how much I disengage from them.

There are two threads here – one invisible thread that binds everything together and a yellow thread that ties itself. Ah … and there is a knife that cuts, but it’s closed. For me, that was the metaphor. I mean, there are all kinds of memories of mine here … it’s actually a kind of buffet of the things I got from my grandparents. And in contrast, there is this invisible thread that strangles everything, that goes into the background and comes out and, like, shackles – that's the word I was looking for – shackles these memories to some kind of abstract – like, to something very unclear.

All my life, from that moment on, I was connected to her eyes, to see if she started to cry. I watch over my mother to keep her from crying, since the mikva, all my life. I mean, my presence is also a kind of … the presence, the tombstone that I am, also puts some responsibility on me for my mother's joy. Not only for the joy, but to stop her from crying.

There was a stage when I suddenly felt like I was suffocating, because I was carrying things inside me that I couldn't handle emotionally … and that was my greatest therapeutic journey – to go looking for the story I didn’t find. It's no longer interesting. But this understanding that I have – no one will conceal it.

Intermodal transfer across three modalities: art, story and interview

The intermodal transition from visual art to the creation of a story may have compelled participants to make an unconscious choice: To what extent should they remain ‘connected’ to the artwork and draw from it to create a story, and to what extent should they ‘disconnect’ the previous work from the new one? The space between the two art forms enabled a variety of reactions. Seven of the participants described the objects they used in their readymade artwork, thus establishing a direct connection between the two art forms. Surprisingly, three participants depicted the connecting materials (which appeared as objects in their artwork and did not have a connector role) as materials that connect objects. In contrast, the visual artwork of three of the participants, who did not make a ‘connection’ between objects in the artwork and the story they created, featured ‘non-functioning’ materials. That is, thread or glue which appear in the artwork but do not fulfill their purpose as binding, sticking, or connecting something. This finding may be seen as reinforcing the themes of connections and the lack of connections. These three participants, who created a ‘disconnection’ between the objects they chose for the story, and whose artworks featured ‘non-functioning’ connecting objects, made various references to connections and the lack of connections in relation to their access to the truth. For example, Eitan said, ‘Suddenly, I can't not put things together.’ And later, ‘Then I start connecting the dots.’ Knowledge of the truth, as these interviews reveal, involves a close encounter with materials that were inaccessible in childhood. Naama describes a memory she has of her parents: as soon as they knew her mother was pregnant, her father began to build a device:

A kind of structure with two metal legs with a transparent plate that holds … and as soon as the baby was born, they put her on the plate that is transparent at the bottom and open at the top, but never on the floor. And that's how she moved through the world, and that's how she experienced everything – never in direct contact with things as they really are. Until the day when a crack formed, and she fell to the ground, and things began, like, to open up.

In conclusion, findings reflect how the themes of connection, disconnection and ambivalent feelings towards integration appear across the different mediums used in the study. They are expressed through the challenges of integrating the story of the secret within the life story, the ruptured and fragmented memories of the experience, and the desire to access concealed information and add it to the sequence of events, as well as the temptation to disengage. The intensive use of glue and thread reinforces these themes, which were also given metaphorical representation in the interviews that validate this experience of a fragmented reality. In addition to shedding more light on the subjective experiences of the participants, findings also demonstrate how intermodal transitions may facilitate the exposure of core issues, enabling clinical work based on metaphors that surface through client’s work with the various art mediums. This will be discussed further below.

Discussion

This research revealed a concrete and intensive utilization of adhesives and other connecting materials in the participants’ readymade artworks and yielded metaphorical lingual expressions that serve to illustrate the different and intermittent ways in which the secret is experienced as ‘connected’ or ‘disconnected.’ The artworks and stories unveil complex, multi-layered implicit memories. The objects in all the artworks remain unattached to the substrate; as they can be dismantled without leaving a trace, they communicate a sense of transience. The materials that could have made them permanent and more tangible are stripped of their original purpose; they become a subject in themselves. This connection/disconnection theme is reinforced in half of the works by the fact that the objects barely touch each other. The impression is that the objects are floating in space, disconnected from each other. Even in the other half of the artworks, in which there is contact between the objects, there is a prominent and extensive use of glue and thread as objects, which may reveal an urgent need for assembly and connection. Themes of connection and disconnection also arose in the intermodal shift from visual art to fictional story, emphasizing the predominance of activities such as fusing, pasting and collecting. It is suggested that growing up in the shadow of a secret may have a significant impact on psychological connections, for instance the connection between known and concealed narratives. There is an apparent connection between those who know the secret and those who don't, as Yasmin puts it: ‘I distanced myself so far from my mother, perhaps because of that secret. Somehow there was a disconnect, which today I seem to be repairing. But there was a very complete disconnect.’ And finally, there is an evident connection between that which is felt and that which remains ‘not connected,’ as Hanna explains in the excerpt cited above.

Bion (Citation1959) coined the concept of attacking on linking, referring to destructive attacks from the psychotic part of the personality directed against all links between objects. That same internalized and destructive object opposes links in thinking, the link between humans and their environment, and even verbal communication and the creation of art work. According to Amir (Citation2018), Bion’s metaphor contains elements of openness and well as concealment. Looking at the unique memory that is part of the experience of growing up in the shadow of a secret, one can distinguish between parts that are revealed to the child in a detached and fragmented way and parts that remain ‘covered’ and unattachable. In this context, it is interesting to mention what Amir (Citation2018) calls ‘the blank traumatic memory;’ in her opinion it is one of the possible derivatives of negative hallucinations, coined by Green (Citation1999). Amir explains that this is not a memory that can be erased because it is not recorded in the first place; it is not an object or even a missing object. It comprises a type of negative, anti-objectified space; this space does not mark absence but repeatedly activates it through the obsessive process of negating continuity. In other words, this type of memory is present as a form of absence; it will be manifested in the fragility of language, and the difficulty to do memory work in empty spaces. The blank memory creates a language of perpetual suspicion and wandering in the dark. As mentioned previously, Yaakov compares his experience to a card trick and describes an increasing lack of ability to see the whole, complete picture that accurately represents reality. Along with the findings that indicate fragmented, severed and incomplete narratives, Hanna’s interview also contains the idea of repair. Hanna portrays the story of a person who insisted on searching for the full truth, who looked for the fragments and the pieces of the family’s narrative. According to Atlas (Citation2022), traumatic experiences are passed down to the next generation and are manifested in elusive ways. Members of the next generation carry within them the former generations, dream their dreams and reproduce the materials that were not revealed to them consciously. In her view, repression is a mechanism that disconnects the memory from its emotional meaning, thereby reducing the importance of the memory and emptying it of meaning. According to Atlas, this disconnect, which comes up again and again, concretely and metaphorically, in the research findings, isolates the trauma and prevents it from being processed.

In conclusion, it is evident that the ability to make connections is undermined when it is not clear what is already connected and what should be connected. A feeling of obscurity and lack lead to an overall experience of unknowing, sometimes described as blindness, when confronted with the fragments of the story. Parallel to the connection/disconnection axis, findings of this study indicate an additional axis representing a continuum between blindness and sight (Sela & Bat Or, Citation2022). Thus, the need to see better using tools allowing reparation or enlargement of objects arose, as well as references for visual impairment. Dealing with the continuum between the revealed and the obscure emphasizes this theme and validates the existence of a multi-layered reality, vague or obscure, which is not initially revealed.

It can be assumed that these two axes encompass the experience of the adult who grew up in the shadow of a hidden secret, and can be an initial starting point when considering therapeutic interventions for this population.

Implications for practice

The present study demonstrates metaphorical work with elusive content that has been integrated in various degrees. The wealth of findings supports this modality of therapeutic work in these contexts. A metaphor establishes a similarity between two different things, helps clarify reality, and lends it meaning (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation2008). Psychotherapy encourages work with metaphors as a means of clarifying complex concepts and obscure feelings; broadening perspectives; and even strengthening the therapeutic relationship (Cirillo & Crider, Citation1995; Lyddon et al., Citation2001; Tay, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Though this is not a psychotherapeutic study, it nevertheless demonstrates how participants’ observation of their readymade artworks and the stories created afterwards spawned a treasure of metaphors that were useful for processing ideas during the interviews, similar to what occurs in an arts-based therapeutic process. For example, when asked, ‘What would you say today to that girl who grew up in the shadow of a secret?’ Yasmin replied, ‘That she should maybe put the magnifying glass away, and look at the whole picture. Because there’s a white chess piece and a black one too, and it’s not a question of good or evil.’ Yasmin, who intuitively chose to feature a magnifying glass in her artwork, presents her wish to expand her perspective; deal with the prices she paid for choosing ‘one side;’ discard the fragmentation mechanism; and create an integrated narrative. The pocketknife that Ofer used in his artwork also later gained a metaphorical meaning that could indicate a possible therapeutic direction: ‘This knife is closed. A closed knife doesn’t cut, the question is what do you do with it. It’s a tool that has not been used yet. The question is – this is always a dilemma regarding these memories – how much I cut from them and assemble something new and how much I disengage from them.’ Ofer's preoccupation with the conflict between cutting away the secret materials from his life on one hand and the desire to assemble a new and integrated story is represented through the pocketknife metaphor. The creative materials and process enables the exploration, or in other words, the consideration of non-verbal content. For example, the thread is not a connector, but in three artworks it serves, as described above, in marking and delineating spaces. Within the therapeutic process, this choice could illuminate a variety of assumptions and associations, including the need for a delineation of spaces; what space belongs to the client and what to others; what is inside the space and what is outside; and what ‘secret’ parts of others permeates into the client’s space. A metaphorical discourse of this kind, based on the artwork and the implicit meanings that it engendered, can open the door to an exploration of emotions, specific nuances of the client’s experience, and treatment goals. In addition, the inter-modal transition between the different arts seems to be extremely effective in producing new materials, and overcoming over-defensiveness and the sense of deadlock. In the context of these sensitive issues of secrecy and concealment and the expression of unknown thoughts it is evident that this transition provides participants an opportunity to broaden their perspectives. This is a subject for further research in the context of clinical interventions.

Study limitations and recommendations for further research

This study used only qualitative tools, so researcher bias is possible as the researchers, in addition to being art therapists, are also psychoanalytic-orientated psychotherapists. It is possible that creating art within an individual’s private home differs from creating in a studio. Researchers from a different clinical field may have interpreted the data differently. Follow-up studies could integrate the tool described in the research procedure in therapeutic processes with this population and add outcome measures in order to test its effectiveness in clinical settings.

Conclusion

This article offers an expansion of the knowledge found in the literature regarding the experience of growing up in the shadow of a secret and points to a subjective experience which relates to attachments and the lack thereof between that which is known and that which was kept secret. The article also offers clinical applications in the field of arts therapy as well as other professions by introducing an inter-modal intervention which combines different art forms and enables the creation of metaphors and contact with implicit components of the experience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tal Sela

Tal Sela is a certified art therapist specializing in drama therapy, a doctoral student at the School of Creative Arts Therapies of the University of Haifa on a Chancellor’s scholarship. She is a psychotherapist, graduate of the Department of Psychology at the University of Haifa and Head of Sector of Art Therapies at the children and youth array at Shalvata Hospital and also a member the hospital’s research team. Tal Sela is a graduate of Haruv Institute in trauma-focused therapy for children and youth studies and supervisor of art therapies students and therapists.

Michal Bat-Or

Michal Bat Or, PhD. is a certified art therapist, an Associate Professor at the School of Creative Arts Therapies, in the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, and a researcher at at The Emili Sagol Creative Arts Therapies Research Center, University of Haifa, Israel. Dr. Bat Or supervises M.A. and Ph.D. students. Michal’s research areas include art therapy therapeutic factors, working alliance in art-therapy, the open studio art-therapy approach, parental representations through clay sculptures, art therapy for trauma and loss, community-based art therapy, art-based interventions in the field of conflict and peace, and art-based assessments: Person Picking an Apple from a Tree, and the Bridge drawing. Art: Michal is the author and illustrator of three children’s books, two of them deals with peace among Arabs-Palestinians and Israelis.

References

- Amir, D. (2018). Bearing witness to the witness: A psychoanalytic perspective on four modes of traumatic testimony. Routledge.

- Arbel, H. (2014). Shlomi kashur b’chut el shlomcha: Hachut v’mashmaouyotav b’tipul b’omanut. [My wellbeing is tied to yours: String and its significance in art therapy]. Psychologia Ivrit. https://www.hebpsy.net/articles.asp?id=3133.

- Atlas, G. (2022). Emotional inheritance. Litlle Brown Spark.

- Baden, A. L., Shadel, D., & Morgan, R. (2019). Delaying adoption disclosure: A survey of late discovery adoptees. Journal of Family Issues, 40(9), 1154–1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19829503

- Bat Or, M., & Megides, O. (2016). Found object/readymade Art in the treatment of trauma and loss. Journal of Clinical Art Therapy, 3(1), 1–30.

- Bat Or, M., & Zusman-Bloch, R. (2022). Subjective experiences of At-risk children living in a foster-care village Who participated in an open studio. Children, 9(8), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9081218

- Betensky, M. G. (1995). What do you see? Phenomenology of therapeutic art expression. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Bick, E. (1968). The experience of the skin in early object relations. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, (49), 484–486.

- Bion, W. R. (1959). Attacks on linking. In Second thoughts: Selected papers on PsychoAnalysis (pp. 93–109). Karnac.

- Birks, M., Chapman, Y., & Francis, K. (2008). Memoing in qualitative research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987107081254

- Blumenfeld, E., & Kadosh, M. M. (2017). Devek, kehomer bayad hayozer [Glue, like clay in the hands of the potter]. Beyn Hamilim, (13).

- Bollas, C. (2017). The shadow of the object: Psychoanalysis of the unthought known. Routledge.

- Bouman, T. K. (2003). Intra- and interpersonal consequences of experimentally induced concealment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(8), 959–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00175-4

- Cirillo, L., & Crider, C. (1995). Distinctive therapeutic uses of metaphor. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 32(4), 511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.32.4.511

- Constantine, M. G., Okazaki, S., & Utsey, S. O. (2004). Self-concealment, social self-efficacy, acculturative stress, and depression in African, Asian, and Latin American international college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.230

- Creswell, J. M. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Creswell, J. M. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. CPI Group.

- Critcher, C. R., & Ferguson, M. J. (2014). The cost of keeping it hidden: Decomposing concealment reveals what makes it depleting. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 721. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033468

- Dominie, R. (2020). Rewiring the nervous system with Art therapy: Advocating for an empirical, interdisciplinary neuroscience approach to Art therapy treatment of traumatized children, A literature review. (master's thesis, Lesley University). 2https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/247.

- Draznin, A. (2018). Family secrets. Sichot, 33(1), 32–43.

- Freud, S. (1990). The uncanny, The penguin Freud library, Art and literature, Vol. 14 (pp. 339–376). Penguin Books.

- Frijns, T. (2004). Keeping secrets: Quantity, quality and consequences. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Frith, L., Blyth, E., Crawshaw, M., & van den Akker, O. (2018). Secrets and disclosure in donor conception. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(1), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12633

- Giorgi, A. P., & Giorgi, B. M. (2003). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In P. M. Camic, J. E. Rhdes, & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 243–274). American Psychological Association.

- Green, A. (1999). The work of the negative, Trans A. Weller (Eds.). Free Association Books.

- Hass-Cohen, N., & Findlay, J. M. C. (2019). The art therapy relational neuroscience and memory reconsolidation four drawing protocol. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 63, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2019.03.002

- Hillix, W. A., Harari, H., & Mohr, D. A. (1979). Secrets. Psychology Today, 13(4), 71–76.

- Imber-Black, E.. (2019). Family secrets. In J. L. Lebow, A. L. Chambers, & D. C. Breunlin (Eds.), Encyclopedia of couple and family therapy (pp. 1119–1125). Springer. https://doi-org.ezproxy.haifa.ac.il/10.1007/978-3-319-49425-8_838

- Janesick, V. J. (2000). The choreography of qualitative research design. In Handbook of qualitative research, Los Angeles: Sage. 379-399.

- Kapitan, L. (2018). Introduction to art therapy research (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Klorer, P. G. (2005). Expressive therapy with severely maltreated children: Neuroscience contributions. Art Therapy, 22(4), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129523

- Knill, P. J., Levine, E. G., & Levine, S. K. (2005). Principles and practice of expressive arts therapy: Toward a therapeutic aesthetics. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2008). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

- Lane, J. D., & Wegner, D. M. (1995). The cognitive consequences of secrecy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(2), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.237

- Larkin, M., Shaw, R., & Flowers, P. (2019). Multiperspectival designs and processes in interpretative phenomenological analysis research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 16(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1540655

- Lusebrink, V. (2014). Art therapy and the neural basis of imagery: Another possible view. Art Therapy, 31(2), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2014.903828

- Lusebrink, V. B. (2004). Art therapy and the brain: An attempt to understand the underlying processes of art expression in therapy. Art Therapy, 21(3), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2004.10129496

- Lyddon, W. J., Clay, A. L., & Sparks, C. L. (2001). Metaphor and change in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(3), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01971.x

- Malik, S. (2022). Using neuroscience to explore creative media in art therapy: A systematic narrative review. International Journal of Art Therapy, 27(2), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2021.1998165

- Margolis, G. J. (1966). Secrecy and identity. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 47(4), 517–522.

- Mazor, A. (2017). Family unformulated knowledge. Epublish.

- Meltzer, D. (1975). Adhesive identification. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 11(3), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1975.10745389

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications.

- Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T., & Varpio, L. (2022). How phenomenology can help US learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-019-0509-2

- Orbach, N. (2019). Studio Tov dayo: Chomer, peula, umerchav batipul baomanut uvechinuch (The good enough studio: Materials, action, and space for education and art therapy): Tel Aviv. Resling.

- Ram-Vlasov, N., & Orkibi, H. (2021). The kinetic family in action: An intermodal assessment model. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 72, 101750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101750

- Ratnarajah, D., & Schofield, M. J. (2008). Survivors’ narratives of the impact of parental suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(5), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.618

- Riley, H. (2013). Exploring the ethical implications of the late discovery of adoptive and donor-insemination offspring status. Adoption & Fostering, 37(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308575913490496

- Rodebaugh, T. L. (2009). Hiding the self and social anxiety: The core extrusion schema measure. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 33(1), 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-007-9143-0

- Sarid, O., & Huss, E. (2010). Trauma and acute stress disorder: A comparison between cognitive behavioral intervention and art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2009.11.004

- Sela, T., & Bat-Or, M. (2022). ‘You have your eyesight and you do not see: "Representations of sight and blindness as manifested in the artistic and verbal expressions of adults who grew up in the shadow of a secret. The Arts in Psychotherapy, (80), 101941.

- Slepian, M., Chun, J., & Mason, M. (2017). The experience of secrecy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000085

- Slepian, M. L. (2022). A process model of having and keeping secrets. Psychological Review, 129(3), 542. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000282

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2022). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Strouse, S. (2014). 42 Collage: Integrating the torn pieces. In Grief and the expressive arts: Practices for creating meaning (pp. 29).

- Talwar, S. (2007). Accessing traumatic memory through art making: An art therapy trauma protocol (ATTP). The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.09.001

- Tay, D. (2020a). Affective engagement in metaphorical versus literal communication styles in counseling. Discourse Processes, 57(4), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2019.1689086

- Tay, D. (2020b). Metaphor in mental healthcare. Metaphor and the Social World, 10(2), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.00007.tay

- Wilson, S., Allen Heath, M., Wilson, P., Cutrer-Parraga, E., Coyne, S. M., & Jackson, A. P. (2022). Survivors’ perceptions of support following a parent’s suicide. Death Studies, 46(4), 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1701144

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. Routledge.

- Wismeijer, A. (2011). Secrets and subjective well-being: A clinical oxymoron. In Emotion regulation and well-being (pp. 307–323). Springer.