?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Niche parties, which have been defined as focusing on a narrow range of issues their competitors neglect, are a phenomenon that has so far been described and analysed primarily in Western Europe. In this paper, we extend existing work by examining the presence and nature of niche parties in Latin America. Using the expert survey data collected by [Wiesehomeier, N., and K. Benoit. 2009. “President, Parties, and Policy Competition.” The Journal of Politics 71: 1435–1447], we show that there are niche parties in most Latin American party systems. Two kinds of niche party, traditionalist and postmaterialist, predominate. We also show that niche parties, despite being defined based on issue-based characteristics, are in fact less programmatic in their linkage strategies than mainstream competitors. Instead, niche parties are slightly more likely to draw on charismatic strategies and tend to establish strong organizational links to ethnic and religious organizations. Niche parties in Latin America are primarily vehicles for the mobilization of group interests. These findings have implications for our understanding of political representation in new democracies and niche party strategies more generally.

Introduction

Recent research on party systems and party competition has focused extensively on niche parties, which are generally defined as parties that focus on certain issues their competitors tend to ignore, with all other parties then classed as “mainstream” competitors (Meguid Citation2005; Meguid Citation2008; Wagner Citation2012; Bischof Citation2017; Meyer and Miller Citation2015).Footnote1 In Europe, there is a clear intuitive appeal to this distinction, as there are certain parties – such as Greens, radical-right populists and regionalists – that have one clear, dominant issue that they are known for and campaign heavily on. In addition to its descriptive usefulness, the niche concept also captures key differences in how parties engage in party competition, as they have been found to differ from mainstream parties in their electoral strategies and in their behaviour. For instance, research has indicated that, unlike their mainstream counterparts, they do not respond to shifts in public opinion (Adams et al. Citation2006, Bischof and Wagner Citation2017), are not electorally rewarded for centrist policy shifts (Adams et al. Citation2006; Ezrow Citation2008), are more sensitive to changes in their own voters’ preferences (Ezrow et al. Citation2010), and differ in their impact on other parties depending on the issue they emphasize (Abou-Chadi Citation2016). The niche–mainstream distinction thus serves important descriptive and theoretical purposes that contribute to our understanding of the role of issues and ideology in party competition.

However, the application of the niche party concept has had a clear regional bias, as it has been used mainly to study party competition in Western Europe. In this paper, we examine whether and how the niche party concept can be applied in Latin America. Are there parties with a narrow issue focus in these party systems? If so, what kinds of parties are they, and how do they differ from their mainstream competitors?

The context of Latin American party systems contrasts starkly with that of Western Europe. Instead of the parliamentary party systems typical of Western Europe, in Latin America presidential multiparty systems are dominant. Moreover, compared to Western Europe, these have evolved differently and vary along different dimensions in terms of their underlying cleavages, the level of institutionalization, and the dominant types of linkages (Dix Citation1989; Mainwaring and Scully Citation1995; Roberts Citation1998; Levitsky Citation1999; Mainwaring Citation1999; Roberts and Wibbels Citation1999; Roberts Citation2002a, Citation2002b; Kitschelt and Kselman Citation2012; Lupu and Riedl Citation2012; Carreras Citation2012; Roberts Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Lupu Citation2014, Carlin, Singer, and Zechmeister Citation2015).Footnote2 Moreover, Latin American party systems have been seen as having lower overall levels of issue-based party competition and higher levels of charismatic and clientelistic linkage strategies (Coppedge Citation2001).

Our measure of party nicheness captures a party policy program’s distinctiveness from all other parties in terms of issue emphasis (Meyer and Miller Citation2015) and is based on expert survey data from 2006/2007 (Wiesehomeier and Benoit Citation2009). It shows that, as in Western Europe, niche parties are present and relevant in many Latin American party systems. However, they have developed differently and campaign on a different set of issues, based on regionally specific cleavages. Specifically, we find that there are two key types of niche party in Latin America: niche parties based on various postmaterialist issues (the environment, decentralization and minority rights) and niche parties based on traditionalist topics such as social values, religion and security. In identifying these parties, our paper contributes to an ongoing effort of cross-national understanding party types in the region (e.g. Altman et al. Citation2009). In addition, we find that niche parties in Latin America are not necessarily smaller, extremer, or younger than mainstream parties.

We also consider whether niche parties are likely to pursue specific linkage strategies, defined as the ideological, material and symbolic benefits politicians and parties try to provide in order to gain political support among voters (Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010, 3; Kitschelt and Kselman Citation2012, 1). While a number of studies have focused on variance in programmatic linkages at the party system level (Roberts Citation2002a; Kitschelt and Kselman Citation2012; Lupu and Riedl Citation2012; Roberts Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Lupu Citation2014; Baker and Greene Citation2015), few studies have so far considered whether some parties prefer certain linkage strategies over others (but see, e.g. Luna Citation2014). At first glance, niche parties in Latin America might seem to be natural candidates for programmatic linkages, given that they are explicitly defined based on issue competition. However, we argue that niche parties need not have strong programmatic linkages to voters. As niche parties can rely on core supporters at elections, they need not appeal to voters on policy terms. Indeed, we argue that niche parties should have strong affect-based linkages via supportive organizations.

Niche parties thus play a distinctive role within Latin American party systems, but perhaps not the one we would intuitively expect. In applying the niche party concept to Latin America, we learn that niche parties indeed exist in Latin America and that they differ in their profile and linkage strategies in comparison to their Western European counterparts. As in Western Europe, many niche parties in Latin America emphasize postmaterialist issues such as the environment, decentralization and minority rights. Unlike in Western Europe, key issues for Latin American niche parties are also traditionalist issues such as social values, religion and security. We find that niche parties are significantly less programmatic than their mainstream counterparts and that different types of niche party employ different linkage strategies. Overall, we learn that the niche party concept does travel to party systems outside of the Western European context, but that such parties take on distinctive roles within Latin American party systems.

The article proceeds by outlining the niche party concept and how it might apply to Latin America. We then map out the extent to which parties differ in their policy profiles and present the parties with the clearest niche profiles across 18 Latin American countries based on data from the 2006/2007 Wiesehomeier and Benoit (Citation2009) expert survey. Empirically, we then use additional data, including the 2007/2008 Democratic Accountability Expert Survey (DAES) carried out by Kitschelt et al. (Citation2010), to analyze the nature of niche parties in Latin America. We conclude by considering potential next steps for research on niche parties in general but also for party research in Latin America.

The niche party concept in Western Europe

The original definition of niche parties was proposed by Meguid (Citation2005), who argued that niche parties (1) reject traditional class-based orientation of politics and (2) emphasize a limited set of issues that (3) go beyond the traditional left–right dimension. This definition captures a set of parties that emerged in Europe due to the rising salience of issues such as the environment, civil rights, immigration and security (Flanagan Citation1987; Inglehart Citation1997; Dalton Citation2009). Examples of such New Politics parties are Green parties, radical-right parties and ethno-territorial parties (Meguid Citation2008). In this initial work, niche party status was operationalized using the family a party belonged to. However, operationalizing niche parties in this way does not allow niche parties to vary their programmatic focus and hence their niche status over time (Wagner Citation2012). Importantly, operationalizing niche parties using party families limits the cross-national applicability of the concept, as it then cannot travel to political systems in which certain party families, e.g. Green parties, do not exist.

More recent attempts to define niche parties have simplified Meguid’s approach and provided a more precise conceptual approach to niche parties that allows researchers to analyze niche parties in any party system. Beginning with the simple observation that parties differ in the extent they emphasize certain policy issues compared to all other parties in the party system, these authors define niche parties by their focus on a limited set of issues their mainstream competitors ignore (Wagner Citation2012; Bischof Citation2017; Meyer and Miller Citation2015). Niche parties are defined through their programmatic offer – the supply side of electoral politics. Instead of distinguishing niche parties by age, ideology, party family or size, this simpler approach to defining niche parties therefore builds on a theoretical conception of the political space and identifies niche parties based on a definition that can travel both backwards and forward in time (Wagner Citation2012, 11). For example, a Green party is not automatically a niche party, but is instead a niche party if it emphasizes the environmental issue in party systems where this issue is comparatively neglected by other parties. This conception of niche parties allows researchers to identify niche parties in any party systems based on ideological niches emerging from any cleavage pertinent to a given party system.

In addition to simplifying and universalizing the concept of a niche party, these recent definitions highlight that “nicheness” is a continuous rather than a binary distinction. Hence, parties differ in the extent they can be described as “niche” competitors, with some parties very clearly mainstream competitors, some clearly niche parties, and others falling somewhere in between the two ideal types. This implies that parties can also increase or decrease their “nicheness” over time. In other words, nicheness is a potentially dynamic characteristic of parties (Meyer and Wagner Citation2013). If necessary, researchers seeking a binary distinction can then use transparently chosen cutoffs on that continuous dimension to identify niche competitors.

Niche parties in Latin American party systems?

The issues that divide voters in Latin America are diverse and differ from those in their counterparts in Western Europe. The key divisions include: state versus market control of the economy, urban versus rural interests, regime support versus regime opposition, evangelical and religious versus secular, democracy versus authoritarianism and indigenous rights (Ruiz Rodríguez Citation2015, 26). In some cases, these divisions even amount to electoral cleavages in the sense of Bartolini and Mair (Citation1990): they have a social-structural component, a collective identity and a durable organization (Bornschier Citation2009).

Given the different cleavages and issue divisions that overall structure party competition, niche parties in Latin America should emphasize different issues than their Western European counterparts. Of course, some issues such as the environment have gained salience in both places, and as in Western European party systems Green parties have emerged in Mexico, Brasil and Colombia. However, other parties have emerged due to distinct local issue divisions: for instance, the Humanist Party in Chile emerged during the dictatorship as a pro-democratic force, exemplifying a party building on the democracy-authoritarian cleavage. In Chile and Uruguay, this cleavage has divided the electorate and structured party competition following the end of the dictatorships in the 1990s (Ruiz Rodríguez Citation2015). In addition, politics in Latin America have been characterized by specific regional cleavages arising from transitions to democracy or multi-ethnic societies. For instance, religious parties have increasingly taken on key roles in political competition (Rodriguez Citation2011). Moreover, several new ethno-territorial parties have emerged based on ethnic cleavages in several countries (such as the Andean region) emphasizing minority rights and decentralization (Van Cott Citation2005; Roberts Citation2012a, Citation2012b). With their strong social-structural component and distinct identities, these cleavages may provide durable bases of support for niche parties. In Latin America, niche parties are thus likely to emerge from different issue divisions and cleavages than in Western Europe.

Given the context of weakly institutionalized party systems and presidentialism, niche parties may also employ different political strategies. The weak institutionalization of several Latin American party systems could facilitate the emergence of niche parties, and the breakdown of mainstream parties has indeed challenged traditional parties and mobilized new political actors in several countries (Roberts Citation2012a, Citation2012b). These weakly institutionalized party systems might foment the emergence of niche parties in particular in contexts where mainstream parties have realigned or broken down.

While weak institutionalism may provide fertile ground for niche parties, presidentialism may potentially limit niche parties’ emergence and electoral strategies compared to niche parties in parliamentary systems. For instance, presidentialism reduces the number of parties in the party systems (Samuels Citation2002), implying less space for niche parties’ inclusion in political competition. Presidentialism additionally creates different incentives for political parties given the predominance of executive elections. Parties must thus aim their electoral strategy towards the national electorate rather than solely towards their party voters. While this is mainly true for large parties, it could have implications for smaller parties that wish to capture the presidency (Samuels Citation2002). Hence, presidentialism is one reason why we might be sceptical about the existence and relevance of niche parties in Latin America.

The distinctiveness of niche parties in Latin America

In this paper, we also consider whether niche parties differ systematically from their more mainstream competitors in more than the issues they emphasize. In Western Europe, niche parties have been found to be younger, smaller and more extreme than mainstream parties (Wagner Citation2012). Does this also apply to niche parties in Latin America? Let us draw on an example from a typical niche party. The Green Party in Brasil emerged at a similar time as European Green Parties, in 1986. It is also a small party: its highest share of the vote in legislative elections was 3.8% (in 2010) while its presidential candidate reached 19.3% of the votes in the same year. Ideologically, it is associated with the left, although it does not officially define its ideology in strictly left–right terms and is open to dialogue with all parties.Footnote3 We expect that niche parties in Latin America are younger, smaller and more extreme than mainstream parties. While we would generally expect niche parties to be young, the age of niche parties depends on the cleavage or issue division it emerged from. Some of these issues may be newer such as the environmental issue, but a niche party can also emphasize an issue that has emerged earlier in the development of the party system.

Hypothesis 1: Niche parties are younger, smaller and ideologically more extreme than mainstream parties.

Next, niche parties in Latin America may be distinctive in terms of the linkage strategies they employ. While extant studies on niche parties have emphasized their programmatic nature, there are reasons to expect differential linkage strategies in the Latin American context. Democratic linkage occurs when politicians or parties provide voters with “policy promises, material benefits and symbolic cues”, with those voters providing electoral support, but also money and voluntary labour, in return (Kitschelt and Kselman Citation2012, 1). Linkage strategies are the efforts politicians undertake to gain political support through such exchange mechanisms, either individually or collectively as parties (Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010, 3). Linkage strategies result from deliberate decisions of parties to build and maintain them (Müller Citation2007, 254).

Most prominent in the literature are programmatic linkage strategies, which require two criteria to be fulfilled at the party level (Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010, 12): (1) key personnel must explicitly and repeatedly take positions on issues or underlying principles that allow them to generate positions on a range of operational policy issues; and (2) the party should be cohesive, in the sense that leading party representatives should not take different stances and contradict each other.Footnote4 For programmatic linkages to be strong, voters therefore need to feel that a party’s platform provides a basic policy orientation to guide a party’s response to changing conditions.

At first glance, it may seem that niche parties should make use of programmatic linkage strategies, given that niche parties are defined by the issues they emphasize. However, niche parties rely on the salience and attractiveness of their primary policy stance(s) (Meguid Citation2005), which is in fact the opposite of a programmatic linkage strategy. Niche parties do not adopt coherent stands on issues that divide the polity, but rather on issues that are neglected by the mainstream parties. This also true for Europe, where radical-right parties tend to blur their position on economic policy (Rovny Citation2013). The narrow focus of a niche profile thus contradicts one element of programmatic strategies, namely that parties rely on comprehensive ideological positions to gain support. Moreover, niche parties are not necessarily particularly cohesive and coherent in their policy stances, as shown for Green parties by Close (Citation2018). Finally, by emphasizing a small range of issues and focusing on their core supporters, niche parties do not take part in a broader effort to attract voters based on policy promises. Instead, they can rely on a solid base of support that shares their core concern and priority. Clearly, niche parties would seem by definition not to be particularly programmatic parties: they do not compete on the most salient issues, may not present cohesive programmes, and may not compete over the same voters as mainstream parties.

Hence, other types of linkage strategy should be more likely to be employed by niche parties in Latin America. First, they may use clientelistic linkage strategies. These are processes whereby parties exchange electoral support for favors in the form of gifts, jobs or preferential access to government programs and services, but do not present ideological platforms (Kitschelt Citation2000). However, clientelistic linkages are generally associated with large governing parties (Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010), so we might doubt whether niche parties are particularly clientelistic.

However, parties can also make use of affective linkage strategies. Most prominently, charismatic linkages allow parties to maintain support based on the party leader’s charisma. Further affective mechanisms include linkage through party identification (emphasizing party history, symbols or rituals), or affective bonds based on descriptive representation such as physical or cultural traits, e.g. ethnicity, region or language (Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010). It is this latter type of linkage strategy that may be particularly relevant for Latin American niche parties. Given their narrow voter base, niche parties should not only develop strategies to link with voters directly, but also to maintain their voter base through organizations linked to their main issue. In Latin America, several organizations, for instance ethnic (Van Cott Citation2005) and religious (Rodriguez Citation2011) groups, have been successful in becoming parties, highlighting the importance of organizational linkage for new parties, particularly if they emphasize religious or ethnic issues. Religious organizations channel key information to faithful voters by emphasizing relevant issues or by endorsing candidates (Boas and Smith Citation2015, 116–117). Moreover, traditionalist niche parties that emphasize issues such as religion and social issues (e.g. abortion or gay rights) may have strong affective linkages via religious belief and should therefore also have stronger links to religious organizations. Postmaterialist niche parties, especially those with a strong emphasis on minority issues and participatory models of democracy, should also have strong links to organizations, here specifically those based on social movements and the protest sector.

Hypothesis 2: Niche parties in Latin America employ charismatic and organisational linkage strategies rather than programmatic or clientelistic strategies.

Niche parties in Latin America: Empirical patterns

To measure the presence of niche parties, we draw on the Wiesehomeier and Benoit (Citation2009) expert survey. This contains cross-sectional data on party positions and their salience across various issues for Latin American parties from 2006/2007; this is still the most complete dataset of party positions and issue salience in the region. We group together all economic issues into one dimension; these issues, on which positions are strongly correlated, are economic cooperation, privatization, globalization and taxes versus spending. Grouping economic issues together means we have information on six issues for all of the 18 countries (i.e. economic issues, social liberalism, the environment, religion, decentralization and liberty versus security), with additional relevant issues available for a subset of countries.Footnote5 See the Appendix for an overview of the issues.

To calculate nicheness, we follow the steps outlined by Meyer and Miller (Citation2015). We choose this measure because it provides a single value on a nicheness scale for each party.Footnote6 Put simply, Meyer and Miller’s measure captures a party policy program’s distinctiveness from all other parties in terms of issue emphasis. To calculate this nicheness value, we use the following formula:where x is the salience value, p is the party and i is the issue. In words, we take the salience on an issue, subtract the mean emphasis the party places on issues in general (excluding the issue itself), then subtract the mean average emphasis other parties place on that issue. We modify Meyer and Miller’s measure slightly to take into account the fact that our data are based on expert surveys and not on party manifestos.Footnote7 We use weighted means for the mean average emphasis other parties place on the issue. We standardize these party vote share weightsFootnote8 to sum to 1 (excluding party p) on policy dimension i. Then, we square this value, add up these values for all issues and then divide this sum by the number of issues before taking the square root. In simple terms, the measure adds up the salience deviations on all policy dimensions and divides by the total number of policy dimensions.

The resulting nicheness measure is easy to interpret. The measure captures a party policy programme’s deviation from all other parties (the relative difference within the party system). As the standardized nicheness score increases, so does a party’s nicheness relative to its rivals. A zero would indicate that the party is as mainstream as an average party, and negative values that a party is more mainstream than the average party.

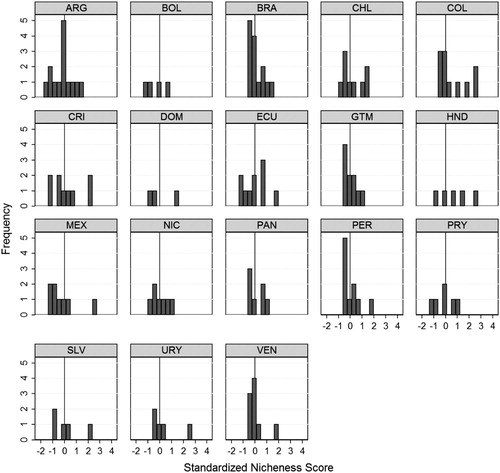

(see appendix) displays the distribution of the standardized nicheness score. This score captures intra-party system variation in nicheness and shows that nicheness has a varied distribution within party systems and across countries. Some are normally distributed, with parties clustered around the mainstream (e.g. Brasil or Guatemala), while others show a more polarized distribution, with parties clustered below and above, but not at the mainstream (e.g. Ecuador). Others have a polarized distribution of nicheness scores with parties at the mainstream (e.g. Bolivia or Honduras).

While our measure is continuous, it makes sense to highlight those parties with the clearest niche profile. In , we include all niche parties with standardized nicheness scores greater than 1. These are parties whose overall programmatic profile is clearly distinctive compared to that of their competitors. To display the issue or issues a niche party emphasizes, we take the policy area with the highest salience deviation from all other parties. If parties had similarly high scores in two issue areas, we included both issues. includes the party, its size, issue salience score, position on that particular issue, and its left–right position. Note that this is just a snapshot of the situation in 2006/2007, and parties can change their nicheness (Meyer and Wagner Citation2013). To take a particularly stark example, we would not expect COPEI in Venezuela, a former governing party, to have been so niche in its programme over its entire history.

Table 1. Niche Parties based on nicheness scores.

The main issues covered by niche parties are the environment, social issues, liberty versus security, indigenous peoples and minorities, decentralization and religion. The remaining issues were not emphasized by niche parties (e.g. economic issues or country-specific issues such as taxing oil revenues). While, like Meyer and Miller (Citation2015), we do not assume a priori that there cannot be economically focused niche parties, our results suggest that Latin American niche parties generally focus on a small range of non-economic issues. We also note that two countries in our dataset do not have niche parties: Bolivia and Paraguay. Here, all parties overall emphasized issues to a similar extent. We suspect that the absence of niche parties in these two countries derives from the dominance of a single party (the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) in Bolivia more recently, and the Colorado Party for over 6 decades in Paraguay). However, we do not further explore this here.

In some countries, niche parties emphasize one or two issues, while in others niche parties emphasize a wider range of issues. For example, in Argentina, we identify one niche party that emphasizes social issues and liberty versus security. Similarly, in Brasil, we identify one niche party that emphasizes the environment and indigenous and minority rights. In Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru and Venezuela niche parties emphasize religion. In countries such as Chile or Colombia we find more varied niche parties. For example, in Chile we identify three niche parties: the Humanist Party emphasized the environment and indigenous and minority rights, the Regionalist Party emphasized decentralization, and the Independent Democratic Union emphasized liberty versus security, social issues and religion. Similarly, three niche parties can be identified in Colombia: ASI, AICO and MAL, three niche parties emphasizing indigenous and minority rights and/or the environment.

Overall, we can identify two main groups of niche parties. The first group includes traditional niche parties emphasizing social issues (e.g. gay rights, euthanasia or abortion) in combination with religion and liberty versus security. Parties in this group include the UDI in Chile, the PRN in Costa Rica, the PRSC in the Dominican Republic or the PDC in Ecuador. A second group includes postmaterialist niche parties emphasizing IPM issues in combination with the environment or decentralization. These are emphasized by the PV in Brasil, the PH in Chile, AICO, ASI and MAL in Colombia, MUPP in Ecuador and EG in Guatemala.Footnote9

The empirical distinctiveness of niche parties in Latin America

In this section, we discuss how niche parties differ from mainstream parties in their size, age, ideological extremism and linkage strategies. These variables were collected from different sources. Party age was gathered from the PDBA database from Georgetown University (http://pdba.georgetown.edu) or party websites. Party size was drawn from Adam Carr’s Electoral Archive (Carr Citation1985–Citation2016). The parties’ ideological position is derived from the Wiesehomeier/Benoit dataset and is based on a scale from 1 to 20, where 1 = left and 20 = right.

Overall, most niche parties are small (i.e. with vote shares under 10% or as a member of an electoral coalition), with a few exceptions such as the UDI in Chile or the PRSC in the Dominican Republic that are close to 20% in their vote shares.

Niche parties also vary in their age. Amongst the older niche parties are the Civic Union in Uruguay (founded in 1910) or the PRSC in the Dominican Republic (1963). Several niche parties emerged in the 1980s and 1990s such as the Humanist Party in Chile (1984), Brasilian Green Party (1986), the Mexican Green Party (1993), the Colombian Indigenous Authority (1990) or Pachakutik Movement in Ecuador (1996). Some of the newest parties include the PRI in Chile (2006) or National Restauration in Costa Rica (2005). Thus, niche parties are not necessarily younger than their mainstream counterparts. They emphasize issues in distinctive ways regardless of the time an issue emerged throughout the development of the party system.

In Latin America, niche parties are spread across the ideological spectrum. On the 1–20 left–right scale, several parties have a left–right score below 9 (the Brasilian Green Party, the Humanist Party in Chile, AICO and ASI in Colombia, MPP in Ecuador, EG in Guatemala, and PUD and PINU in Honduras). The remaining niche parties have a score above 12 (FrePoBo in Argentina, PRI in Chile, UDI in Chile, MAL in Colombia, PRN and PRC in Costa Rica, PRSC in Dominican Republic, PDC in El Salvador, PVEM in Mexico, PRN in Nicaragua, PP in Panama, RN in Peru, Copei in Venezuela and UC in Uruguay). The party furthest to the left is the Pachakutik Movement in Ecuador (with a left–right position of 3.6), while the party furthest to the right is the UDI in Chile (with a left–right position of 18.1). Overall, the correlation coefficients for the nicheness score and party age (.09), vote shares (−.10) and distance from the center of the left–right scale (.07) do not provide evidence in support of Hypothesis 1.

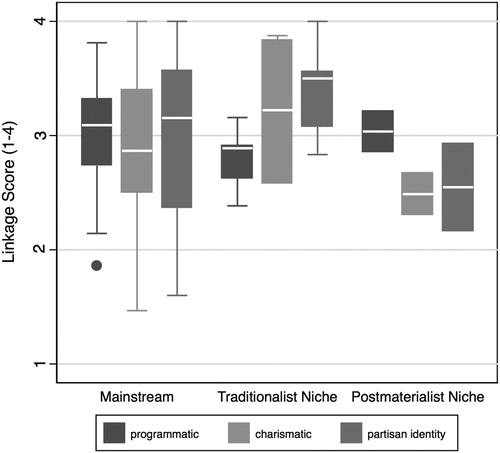

Finally, we determine the association between nicheness and party linkage strategies. Our main dependent variable is “linkage”; information on linkage strategies is taken from the 2007/2008 DAES expert survey (Kitschelt et al. Citation2010). To assess organizational linkage, the experts were asked to indicate whether a given party has strong (1) or weak (0) linkages. The mean expert score per party ranged between these two values, and we use this mean expert score per party as the dependent variable. The survey also asks experts to assess programmatic linkages by indicating the extent to which parties seek to mobilize electoral support by emphasizing the attractiveness of the party’s positions on policy issues. To check if the niche parties employ alternative linkage based on partisan identification, and charismatic linkages. The charismatic linkages question is phrased: “To what extent do parties seek to mobilize electoral support by featuring a party leader’s charismatic personality?” The partisan identity indicator is phrased: “Please indicate the extent to which parties draw on and appeal to voters’ long-term partisan loyalty (party identification)”. For programmatic, charismatic and affective linkages, the response options range from 1 (not at all) to 4 (to a great extent). See the Appendix for the exact questions and the distribution of these variables ().

Our main predictor variable is the standardized nicheness score that indicates party nicheness, as presented above. We lose some, mainly smaller parties and all Venezuelan parties when merging the datasets, leaving us with 80 parties in 17 countries. We include party age (logged), parties’ ideological placement (including a squared term to account for non-linearities), party size and a further potentially confounding variable: electoral strategy. This variable taps into the nature of decision-making within a party and its degree of nationalization. It is derived from the DAES and based on a scale where experts were asked to state at which level a party’s electoral strategy is determined (1 = nationally, 2 = regionally, 3 = inter-level bargaining and 4 = locally). We recode this into a dichotomous variable where 0 represents a score less than the experts’ mean score and 1 a score that is greater than experts’ mean score.

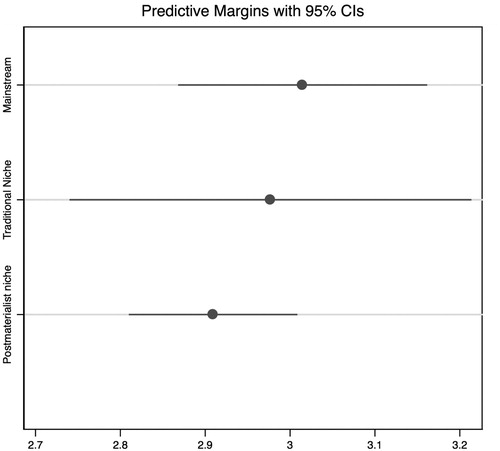

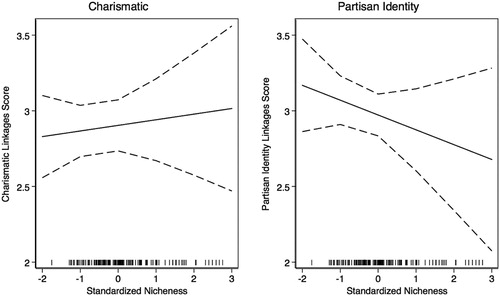

We employ ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions to test Hypothesis 2 given the continuous nature of our dependent variables. The regression models with country-level clustered standard errors are presented in .Footnote10 First, Model 1 shows that, as a party’s nicheness score increases, it is less likely to pursue programmatic linkage strategies. The effect is a .11 reduction in programmatic linkages for every one-unit increase in nicheness, significant at the .01 level. Second, Models 2 and 3 show that niche parties do not differ significantly from mainstream parties in the charismatic or partisan identity linkage strategies. Model 2 shows that parties that devise their electoral strategy on the local/regional level are significantly less likely to employ charismatic linkage.

Table 2. Empirical analysis: the effect of nicheness of linkage strategies.

Finally, niche parties overall have stronger links to religious and ethnic organizations (Models 4 and 5, respectively). This provides support for the theoretical expectation that niche parties are more likely to have strong links to these types of organizations. The effect is much stronger for the organizational linkages between niche parties and ethnic organizations (here a one-unit increase in nicheness leads to an increase in organizational linkage strength by .2) than for religious organizations (where a one-unit increase in nicheness leads to an increase in organizational linkage strength by .1).

We find slight differences between postmaterialist niche, traditional niche and mainstream parties. We test this by creating dummy variables for traditional niche parties (religion, social issues and liberty versus security), and postmaterialist niche parties (IPM, environment and decentralization).Footnote11 The Appendix includes the models in disaggregated by niche party type. Particularly postmaterialist niche parties have weaker programmatic linkage strategies than mainstream parties; they also have weaker such linkages than traditionalist niche parties. Being postmaterialist reduces expert assessments of programmatic linkages by 0.2 (significant at the .01 level) on the 1-4 scale compared to mainstream parties. The level of charismatic linkages increases by .34 for traditionalist niche parties, and decrease by .08 for postmaterialist niche parties, compared to mainstream parties. Last, we find a similar effect for partisan identity linkages: partisan identity linkage strategies increase by .38 for traditional niche parties, and decrease by .28 for postmaterialist niche parties. We find here that traditionalist niche parties are much more likely to employ partisan identity and charismatic linkage strategies than postmaterialist niche parties and mainstream parties. This is not surprising since several of the traditionalist niche parties are parties with longer party traditions (e.g. the UDI in Chile, the UC in Uruguay and COPEI in Venezuela) compared to the postmaterialist parties, which are often relatively new. Overall, traditionalist niche parties engage in differential linkage strategies compared to postmaterialist parties and are significantly more likely to stress charismatic aspects as well as partisan identity, rituals and symbols.

The marginal effects for postmaterialist and traditionalist niche parties show slight evidence (though insignificant) that postmaterialist niche parties are more likely to have strong links to ethnic organizations, while traditionalist niche parties tend to have slightly stronger links to religious organizations. Regarding linkages to religious organizations, the strength of organizational linkages increases for traditionalist niche parties by .11 compared to mainstream parties. In terms of linkages to ethnic organizations, the strength of postmaterialist niche parties’ linkages to ethnic organizations increase by .35 compared to mainstream parties. The difference between groups is not significant at the 5% level. & in the Appendix show the marginal effects of party type on programmatic linkages and the effect of nicheness on alternative linkages.

Discussion and conclusion

Niche parties have mostly been associated with established democracies in Western Europe. We show that there are clearly identifiable niche parties across Latin American party systems. Hence, the niche party concept does apply to Latin America, and this analytical distinction may be useful in understanding how different types of parties compete within and across party systems. This contributes to an ongoing effort of cross-national understanding party types in the region (e.g. Altman et al. Citation2009). Measuring the presence of niche parties in Latin American systems is important as they are very different from Western European party systems in terms of their history, stability and institutional context.

We showed that there are two key types of niche party in Latin America: those focusing on postmaterialist issues such as the environment, decentralization and minority rights, and those focusing on traditionalist topics such as social values, religion and security. Examples of the first are parties such as Movimiento Pachakutik in Ecuador, the Green parties in Brasil and Mexico, AICO in Colombia or the no longer existing Humanist Party in Chile; examples of the second are parties such as National Renovation in Peru, the Independent Democratic Union in Chile, or the defunct FrePoBo in Argentina. Distinguishing between types of niche party provides important nuances, and our distinction is perhaps analogous to that comparing Green and radical-right parties in Europe (Abou-Chadi Citation2016).

Niche parties are generally relatively small parties in terms of their vote share, but are not necessarily younger or more extreme. For instance, niche parties in Latin American party systems are older because they emphasize issues in distinctive ways regardless of the time an issue emerged throughout the development of the party system. This may mean that older issues, such as religion, have not been absorbed by mainstream parties, or that certain cleavages have not yet been “resolved”. In terms of their linkage strategies, they are significantly less programmatic than their mainstream counterparts. The more narrow a party’s issue focus, the less it tends to appeal to voters on ideological grounds. We also found that postmaterialist niche parties are particularly unlikely to use programmatic linkage strategies.

Moreover, we also found that postmaterialist and traditional niche parties differ substantially in the other linkage strategies they employ. Traditionalist niche parties tend to use charismatic and partisan identity linkage strategies more than other parties. They also have strong links to religious organizations. In contrast, postmaterialist niche parties have relatively strong links to ethnic organizations and are less likely to employ all types of linkages compared to mainstream parties. As ethnicity is one of their central issues, postmaterialist niche parties might resort to alternative affective bonds based on physical and cultural traits (descriptive representation) as a means to support long-term allegiance (Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010). Postmaterialist niche parties may possibly create linkages through mechanisms not covered in the existing data. Overall, the differentiated findings on postmaterialist versus traditionalist niche parties underscore recent findings pointing to differences between types of niche party.

Regarding the literature on Latin American parties, we contribute by studying the nature of linkage strategies at the party level. Most research on linkage in Latin America has compared political and party systems as a whole (Kitschelt et al. Citation2010; Roberts Citation2012b). We analyze different linkage strategies in order to understand which parties draw on which strategies. While the widespread use of clientelistic strategies among mainstream parties such as the Justicialist Party in Argentina is well-known (Auyero Citation2002; Freidenberg and Levitsky Citation2007; Weitz-Shapiro Citation2014), empirical evidence as to which parties use different linkages based on their place in party systems has been lacking. Our findings point to issue strategies as an important correlate of linkage strategies. We find that some niche parties – particularly traditionalist ones – often use linkage strategies based on charisma or partisan identity, and that niche parties in general have stronger ties to external organisations. There is thus a link between types of issue-based party competition and types of linkage strategies that future research should explore further.

Future research should focus on niche party strategies and behaviour. Here, researchers can build on work on party systems in Europe. For instance, how do niche parties shape political agendas (e.g. Wagner and Meyer Citation2016)? How do mainstream parties react to niche party success (e.g. Meguid Citation2008)? And are niche parties less responsive to public opinion than mainstream parties in Latin America (e.g. Ezrow et al. Citation2010)?

Finally, there are democratic implications to the presence of niche parties in Latin America. The lower level of programmatic strategies among these parties can be linked to the more general concern about the direction of democratic development and the implications of the emergence of new parties (Carreras Citation2012; Roberts Citation2012a, Citation2012b). However, we also found that niche parties have particularly strong organizational links, even though these have generally been declining. This has implications for the incorporation of group interests in politics. Niche parties may act as key vehicles to include such interests in the political arena. The democratic role and implications of the presence of niche parties deserve to be discussed further.

Overall, research on niche party linkage strategies from a cross-national perspective could be extended to cover over regions such as Eastern Europe and Asia, where the development of party systems and the nature of linkage strategies remain up for debate. Future research should also endeavor to collect additional data across a wide range of countries to allow researchers to measure a fuller range of characteristics for more parties over an extended period of time. A greater range of data will enable researchers to answer more complex questions concerning the evolution and direction of party systems and linkage strategies in Latin America and elsewhere.

Appendix1.pdf

Download PDF (492.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Theresa Kernecker is a doctoral candidate at the Department of Government at the University of Vienna, Austria.

Markus Wagner is a Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Vienna, Austria.

Notes

1 Early approaches to studying niche parties focused on their non-centrist ideology (Adams et al. Citation2006; Ezrow et al. Citation2010), but this definition has become less common. More recently, researchers have moved from binary niche-mainstream definitions towards studying the ‘nicheness’ of party profiles (Meyer and Miller Citation2015).

2 Recent critical junctures in the region have had differential effects on party systems' programmatic profile: some party systems fragmented, opening spaces for extreme parties, while other systems realigned along programmatic lines leading to stable coalitions (Roberts Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

3 See http://pv.org.br/opartido/programa/. The Mexican Green Party (PVEM) was founded at a similar time and is also small in terms of vote share, but has a tradition of forming coalitions with one of the mainstream parties (PRI) (Spoon and Pulido Gómez Citation2017).

4 At the party system level, Roberts (Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2014) identifies three further requirements for a system to qualify as programmatic (see also Kitschelt and Freeze Citation2010): parties must adopt relatively coherent stands on salient issues that divide the polity; meaningful differences must exist in the policy alternatives offered by major competing parties; and policies adopted by a public office resemble the platform on which it ran.

5 Some issues (e.g. relations with Nicaragua, oil revenues or Plan Colombia) are only included in certain countries. Further issues (e.g. indigenous peoples and minorities, certain economic issues or party regulation) are asked in several, but not all countries.

6 The measures proposed by Wagner (Citation2012) and Bischof (Citation2017) are less straightforward but capture a very similar conceptualization.

7 In party manifestos, salience data are compositional: all emphases must sum to 1. This does not apply to expert surveys. Instead, we subtract a party’s mean issue salience on other issues to account for the fact parties differ in the overall resources they have in terms of active politicians, media attention and money.

8 Party weights are based on vote shares collected from Adam Carr’s Election Archive and secondary sources such as electoral or legislative institutions.

9 Only one party, the Christian Democratic Party in El Salvador, combines niche emphasis on both traditional and postmaterialist issues. We code this party as a traditionalist niche party.

10 We also ran multilevel regressions, but variance on the country level was very low. In additional robustness checks, we controlled for country-level variables such as GDP, Gini Index, poverty, indigenous population and a market economy index. However, these variables correlated highly and did not have a strong impact other coefficients in our models.

11 Decentralization fits into the postmaterialist category as part of a broader process of democratization and reaching previously neglected sectors of the electorate. Liberty versus security is more of a traditional ‘materialist’ issue, even if it emerged recently following democratization in Latin America as part of the democracy–authoritarian cleavage.

References

- Abou-Chadi, T. 2016. “Niche Party Success and Mainstream Party Policy Shifts – How Green and Radical Right Parties Differ in Their Impact.” British Journal of Political Science 46: 417–436. doi: 10.1017/S0007123414000155

- Adams, J., M. Clark, L. Ezrow, and G. Glasgow. 2006. “Are Niche Parties Fundamentally Different from Mainstream Parties? The Causes and Electoral Consequences of Western European Parties’ Policy Shifts, 1976–1998.” American Journal of Political Science 50: 513–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00199.x

- Altman, D., J. P. Luna, R. Pinieiro, and S. Toro. 2009. “Parties and Party Systems in Latin America: Approaches Based on an Expert Survey 2009 [in Spanish].” Revista de Ciencia Politica 29: 775–798.

- Auyero, J. 2002. “Political Clientelism: A Double Life and Collective Negation [in Spanish].” Perfiles Latinoamericanos 1: 33–52.

- Baker, A., and K. Greene. 2015. “Positional Issue Voting in Latin America.” In The Latin American Voter, edited by Ryan Carlin, Matt Singer, and Zechmeister Elizabeth, 173–195. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Bartolini, S., and P. Mair. 1990. Identity, Competition, and Electoral Availability. The Stabilization of European Electorates 1885-1985. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bischof, D. 2017. “Towards a Renewal of the Niche Party Concept: Parties, Market Shares and Condensed Offers.” Party Politics 23 (3): 220–235. doi:1354068815588259 doi: 10.1177/1354068815588259

- Bischof, D., and M. Wagner. 2017. “What Makes Parties Adapt to Voter Preferences? The Role of Party Organization, Goals and Ideology.” British Journal of Political Science. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000357

- Boas, T., and A. Smith. 2015. “Religion and the Latin American Voter.” In The Latin American Voter, edited by Ryan Carlin, Matt Singer, and Elizabeth Zechmeister, 99–121. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Bornschier, S. 2009. Cleavage Politics in Old and New Democracies. Living Reviews in Democracy, 1. https://www.lrd.ethz.ch/index.php/lrd/article/viewArticle/lrd-2009-6.

- Carlin, R., M. Singer, and E. Zechmeister, eds. 2015. The Latin American Voter: Pursuing Representation and Accountability in Challenging Contexts. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Carr, A. 1985–2016. Adam Carr’s Election Archive. http://psephos.adam-carr.net/.

- Carreras, M. 2012. “Party Systems in Latin America after the Third Wave: A Critical Reassessment.” Journal of Politics in Latin America 4: 135–153.

- Close, C. 2018. “Parliamentary Party Loyalty and Party Family: The Missing Link?” Party Politics 24 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1177/1354068816655562.

- Coppedge, M. 2001. “Political Darwinism in Latin America’s Lost Decade.” In Political Parties and Democracy, edited by Larry Diamond and Richard Gunther, 173–205. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Dalton, R. 2009. “Economic, Environmentalism and Party Alignments: A Note on Partisan Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies.” European Journal of Political Research 48: 161–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00831.x

- Dix, R. 1989. “Cleavage Structures and Party Systems in Latin America.” Comparative Politics 22: 23–37. doi: 10.2307/422320

- Ezrow, L. 2008. “Research Note: On the Inverse Relationship Between Votes and Proximity for Niche Parties.” European Journal of Political Research 47: 206–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00724.x

- Ezrow, L., C. De Vries, M. Steenbergen, and E. Edwards. 2010. “Mean Voter Representation and Partisan Constituency Representation: Do Parties Respond to the Mean Voter Position or to Their Supporters?” Party Politics 17: 275–301. doi: 10.1177/1354068810372100

- Flanagan, S. 1987. “Value Change in Industrial Societies.” American Political Science Review 81: 1303–1319.

- Freidenberg, F., and S. Levitsky. 2007. “Informal Organization of Parties in Latin America [in Spanish].” Desarrollo Economico 46: 539–568.

- Inglehart, R. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kitschelt, H. 2000. “Linkages Between Citizens and Politicians in Democratic Polities.” Comparative Political Studies 33: 845–79. doi: 10.1177/001041400003300607

- Kitschelt, H., and K. Freeze. 2010. “ Programmatic Party System Structuration: Developing and Comparing Cross-National and Cross-Party Measures with a New Global Data set.” APSA Annual Meeting, Washington, DC.

- Kitschelt, H., and D. Kselman. 2012. “Economic Development, Democratic Experience, and Political Parties’ Linkage Strategies.” Comparative Political Studies 46: 1453–1484. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453450

- Kitschelt, H., J. P. Luna, G. Rosas, and E. Zechmeister. 2010. Latin American Party Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Levitsky, S. 1999. “Fujimori and Post-Party Politics in Peru.” Journal of Democracy 10: 78–92. doi: 10.1353/jod.1999.0047

- Luna, J. P. 2014. Segmented Representation: Political Party Strategies in Unequal Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lupu, N. 2014. “Brand Dilution and the Breakdown of Political Parties in Latin America.” World Politics 66: 561–602. doi: 10.1017/S0043887114000197

- Lupu, N., and R. Riedl. 2012. “Political Parties and Uncertainty in Developing Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 46: 1339–1365. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453445

- Mainwaring, S. 1999. Rethinking Party Systems in the Third Wave of Democratization: The Case of Brazil. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Mainwaring, S., and T. Scully. 1995. Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Meguid, B. 2005. “Competition Between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success.” American Political Science Review 99: 347–359. doi: 10.1017/S0003055405051701

- Meguid, B. 2008. Party Competition Between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meyer, T., and B. Miller. 2015. “The Niche Party Concept and its Measurement.” Party Politics 21: 259–271. doi: 10.1177/1354068812472582

- Meyer, T., and M. Wagner. 2013. “Mainstream or Niche? Vote-Seeking Incentives and the Programmatic Strategies of Political Parties.” Comparative Political Studies 46: 1246–1272. doi: 10.1177/0010414013489080

- Müller, W. C. 2007. “Political Institutions and Linkage Strategies.” In Patrons, Clients, and Policies, edited by Herbert Kitschelt and Steven Wilkinson, 251–275. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Roberts, K. 1998. Deepening Democracy? The Modern Left and Social Movements in Chile and Peru. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Roberts, K. 2002a. “Party-Society Linkages ad Democratic Representation in Latin America.” Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 27: 9–34.

- Roberts, K. 2002b. “Social Inequalities Without Class Cleavages in Latin America’s Neoliberal era.” Studies in Comparative International Development 36: 3–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02686331

- Roberts, K. 2012a. “Market Reform, Programmatic (De)alignment, and Party System Stability in Latin America.” Comparative Political Studies 46: 1422–1452. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453449

- Roberts, K. 2012b. “Parties, Party Systems, and Political Representation.” In Routledge Handbook of Latin American Politics, edited by Peter Kingstone and Deborah Yashar, 48–60. London: Routledge.

- Roberts, K. 2014. Changing Course in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Roberts, K., and E. Wibbels. 1999. “Party Systems and Electoral Volatility in Latin America: A Test of Economic, Institutional, and Structural Explanations.” American Political Science Review 93: 575–590. doi: 10.2307/2585575

- Rodriguez, C. 2011. Religion and Politics in Latin America [in Spanish]. Latin American Parliamentary Elite Project (Report) 27: 1–8.

- Rovny, J. 2013. “Where do Radical Right Parties Stand? Position Blurring in Multidimensional Competition.” European Political Science Review 5: 1–26. doi: 10.1017/S1755773911000282

- Ruiz Rodríguez, L. 2015. “Oferta partidista y comportamiento electoral en America Latina.” In El Votante Latinoamericano, edited by Helcimara Telles and Alejandro Moreno, 19–38. Mexico City: Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinion Publica.

- Samuels, D. 2002. “Presidentialized Parties.” Comparative Political Studies 35: 461–483. doi: 10.1177/0010414002035004004

- Spoon, J., and A. Pulido Gómez. 2017. “Unusual Bedfellows? PRI–PVEM Electoral Alliances in Mexican Legislative Elections.” Journal of Politics on Latin America 9 (2): 63–92.

- Van Cott, D. 2005. From Movements to Parties in Latin America: The Evolution of Ethnic Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wagner, M. 2012. “Defining and Measuring Niche Parties.” Party Politics 18: 845–864. doi: 10.1177/1354068810393267

- Wagner, M., and T. Meyer. 2016. “The Radical Right as Niche Parties? The Ideological Landscape of Party Systems in Western Europe, 1980–2014.” Political Studies. doi:10.1177/0032321716639065.

- Weitz-Shapiro, R. 2014. Curbing Clientelism in Argentina. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wiesehomeier, N., and K. Benoit. 2009. “President, Parties, and Policy Competition.” The Journal of Politics 71: 1435–1447. doi: 10.1017/S0022381609990193