ABSTRACT

This study focuses on immigration news as driver of anti-immigrant party support. Predicting the poll results of the Dutch Freedom Party (PVV), we distinguish between (a) general immigration news, news in which immigration is linked to (b) crime, (c) terrorism, or (d) the economy, and (e) immigration news in which the Freedom Party is mentioned explicitly. Focusing on the period 2004–2017, an extensive dataset has been generated using computer-assisted content analyses of media coverage (n = 1,697,976), public opinion data, and real-world indicators. Time-series analyses demonstrate a positive impact of general immigration news on anti-immigrant party support – and not on the support for other parties. No media effects are found for the immigration sub-issues or the visibility of the Freedom Party in the news. However, the main competitor on the right side of the political spectrum – the Liberal Party (VVD) – may also benefit from immigration news but only when it manages to be linked to the issue in the media coverage. Our results raise relevant questions about the preconditions of issue ownership effects, and show how issue ownership is a highly contested political asset in a fragmented and competitive multiparty system.

Since the turn of the century, anti-immigrant parties have been on the rise throughout Western Europe (Mudde Citation2013). The Netherlands is no exception: The Freedom Party (PVV) led by Geert Wilders became the second largest party in the 2017 Parliamentary elections. To understand the popularity of anti-immigrant parties, research points to the news media as a key contextual-level factor (e.g. Walgrave and de Swert Citation2004, Citation2007; Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2007; Burscher, van Spanje, and de Vreese Citation2015). By repeatedly paying attention to specific issues, media raise issue-related public concerns, subsequently increasing citizens’ likelihood to cast their vote on the basis of these salient issues. Such agenda-setting and priming processes (Scheufele and Tewksbury Citation2007) make that anti-immigrant parties may benefit from media attention for the immigration issue, which is empirically confirmed by several studies (e.g. Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2007; Sheets, Bos, and Boomgaarden Citation2016).

A key concept underlying this media effect is issue ownership, which refers to the associations between political parties and political issues in the minds of voters. The party that is most strongly linked to an issue is considered to “own” it (Walgrave, Tresch, and Lefevere Citation2015). Research indicates that in many countries, relatively new anti-immigrant parties succeeded in quickly becoming the most prominent and identifiable owner of the issue of immigration (e.g. Mudde Citation1999). Accordingly, more media attention for the immigration issue is likely to be most beneficial for this type of party and should have less consequences for other parties.

While a substantial literature exists on the impact that immigration news may have on support for anti-immigrant parties, not much is known about the content characteristics that determine this impact. Our aim is to unpack issue ownership effects over time by specifying immigration news effects in two ways. First, we examine whether and to what extent the presence of certain attributes in immigration news are a(n additional) driver of electoral support (relying on second-level agenda-setting; Scheufele and Tewksbury Citation2007). Building on group conflict theory, we distinguish between general immigration news and news in which immigration is linked to the issues with which anti-immigrant parties often associate it (Vossen Citation2009, Citation2011): crime, terrorism, and the economy. Second, we explore whether and to what extent the visibility of political parties in the news matters for electoral popularity. As Walgrave and de Swert (Citation2007) rightfully pointed out, one of the key sources of issue ownership – especially for newer, challenging parties – is mass media coverage. We examine whether being linked to the immigration issue in the news is a prerequisite for the Freedom Party to benefit from immigration coverage, and to what extent this also applies to parties not owning the issue.

To answer these questions we rely on Dutch data. The Netherlands provides an excellent case study because it witnessed the (early) rise of one of the most influential contemporary anti-immigrant parties of Western Europe: The Freedom Party led by Geert Wilders. Furthermore, the Dutch political context is characterized by a highly fragmented multi-party system in which competition over issues between parties tends to be fierce (e.g. Aalberg and Jenssen Citation2007). The current study covers the period that the forerunner of this party was founded (September 2004) until the most recent period for which data were available (December 2017). An extensive dataset of 1,697,976 newspaper articles was analyzed and effects of news coverage on Freedom Party support were compared with effects on support for other political parties. The high popularity of the anti-immigrant party family, with its radical outlook on immigration, calls for a thorough understanding of the sources of its success, and our results suggest that news coverage is among the most decisive ones.

Immigration news and anti-immigrant party support

Agenda-setting theory explains how news media are able to set the public agenda by making some issues more salient at the expense of other issues (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Van Aelst and Walgrave Citation2011). Concretely, the more news about a certain topic (e.g. immigration), the more accessible this issue becomes in the minds of citizens. Priming theory assumes that these most accessible issues subsequently serve as evaluation criteria in judgments of political actors, for example at the ballot box (e.g. Iyengar and Kinder Citation1987; Scheufele and Tewksbury Citation2007). Arguing along the lines of issue ownership theory, it is likely that parties will profit electorally from a larger salience of the specific issue of which they are perceived to be the “owner” (e.g. Budge and Farlie Citation1983; Ansolabehere and Iyengar Citation1994; Petrocik Citation1996). Hence, substantial news attention for immigration should result in an advantage for anti-immigrant parties, since the topic that is considered to belong to their “core expertise” is being highlighted and made salient. This assumption is empirically confirmed by several studies (e.g. Walgrave and de Swert Citation2004; Vliegenthart and Boomgaarden Citation2007; Burscher, van Spanje, and de Vreese Citation2015; Sheets, Bos, and Boomgaarden Citation2016).

Similar to most types of political information, issue ownership is conveyed to the voter by the mass media (Walgrave and de Swert Citation2007). Parties promote issues on which they hold a reputation of competence (Green and Hobolt Citation2008, 462), but they need the mass media to pick up their messages and convert it into mediated content. Although there are certainly ways for parties to conquer or “steal” issue ownership from another party, research suggests that on the macro-level issue ownership tends to be rather stable over time, not the least because also the media often maintain existing associations between parties and issues (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Nuytemans Citation2009; Kleinnijenhuis and Walter Citation2014). Other parties, which do not own the issue, may not benefit from increasing immigration news visibility. These considerations are formalized into the first two hypotheses:

H1: Increasing immigration visibility in the news leads to higher levels of anti-immigrant party support.

H2: Increasing immigration visibility in the news does not lead to higher levels of support for other political parties.

Research indeed shows that the media cover immigration frequently from such a “threat” perspective (Van der Linden and Jacobs Citation2016). Immigration has been portrayed as a phenomenon that puts the welfare system of the host society under pressure or gives rise to competition at the labor market. At the same time, immigration is often presented as a threat to the native population’s safety since immigrants are associated with rising crime levels or even the propensity to commit terrorist attacks (Dinas and van Spanje Citation2011; Quinsaat Citation2014; Caviedes Citation2015; Dixon and Williams Citation2015). Such value-laden news messages have been found to affect public opinion and cause negative views about immigrants (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2009; Van Klingeren et al. Citation2014; Atwell Seate and Mastro Citation2016; Van der Linden and Jacobs Citation2016). Coverage in which the immigration issue is explicitly linked to these types of threats is, therefore, expected to increase support for anti-immigrant parties but, again, not support for other political parties. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3: Increasing immigration visibility in the news, in which the issue is linked to (a) crime, (b) terrorism, and (c) the economy, leads to higher levels of anti-immigrant party support.

H4: Increasing immigration visibility in the news, in which the issue is linked to (a) crime, (b) terrorism, and (c) the economy, does not lead to higher levels of support for other political parties.

Whereas the associative dimension tends to be stable over time, the competence dimension is more volatile (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Nuytemans Citation2009). The media play an essential role here. Media reinforce existing ownerships by paying attention to a certain issue, with or without mentioning the party already owning it. But they also establish new identifications between parties and issues when they repeatedly and consistently link another party to an issue (Walgrave and de Swert Citation2007); for example, when a party delivers the minister responsible for the issue and the media extensively cover his/her performance in terms of proposed policies (see also Hopmann et al. Citation2010; Geers and Bos Citation2017). This implies that political parties not owning the immigration issue, may still benefit from immigration news as long as the media explicitly link the issue to them. Especially in a multiparty system – like the Dutch one – with many parties competing for a limited number of issues, parties that are ideologically close constantly try to overtake issue ownership from their competitors (Aalberg and Jenssen Citation2007). While “stealing” an issue in terms of associative ownership is not likely to occur often, parties can be successful in increasing their reputation on policy issues and thus (partly) gaining ownership in terms of competence.

We therefore expect immigration news in which the anti-immigrant party is mentioned to cause higher levels of support because this news will reinforce (associative) issue ownership. However, when the media explicitly link another party to the immigration issue, these parties may also benefit from higher immigration issue salience – as it may contribute to their competence ownership. These expectations lead to the final set of hypotheses:

H5: Increasing immigration visibility in the news, in which the issue is linked to the Freedom Party leads to higher levels of anti-immigrant party support.

H6: Increasing immigration visibility in the news, in which the issue is linked to the (a) Liberal Party; (b) Labor Party, or (c) Christian Democrats, leads to higher levels of support for these political parties.

Empirical background: the Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands

Over the last decades and alike other Western European countries, the Netherlands has witnessed the rise of strong and viable anti-immigrant parties of which the Freedom Party (PVV) has been the most successful one. The Freedom Party, organized around leader Geert Wilders, mobilized itself on the emerging cleavage following globalization and immigration, and has ever since attracted large electoral support while campaigning mainly on the immigration issue (Bos and van der Brug Citation2010). Empirical studies and theoretical observations assessing the Freedom Party’s manifestos conclude that this party meets the criteria of a right-wing populist party with a fierce anti-immigration stance (Vossen Citation2010; Mudde Citation2013). It employs a rhetoric in which immigration is consistently presented as an urgent threat to the safety and well-being of citizens. The Chapel Hill Expert Survey indicates that of all Dutch parties the Freedom Party holds the most negative position toward immigrants. In addition, for none of the other parties the immigration issue is judged as salient as it is for the Freedom Party, followed by the Liberal Party that scores considerably lower.Footnote1 Furthermore, content analyses of party manifestos (cf. Parties’ Immigration and Integration Positions dataset) show that of all Dutch parties the immigration issue is most salient in Freedom Party documents.Footnote2 Finally, empirical research indicates that the Freedom Party is most often mentioned by voters when asked which party they consider the owner of the immigration issue (Geers and Bos Citation2017, 13).

Officially founded in 2006 by Geert Wilders (who left the Liberal Party in 2004, starting forerunner “Groep Wilders”), the Freedom Party has gradually obtained electoral successes. In addition to its anti-immigration agenda, the Freedom Party takes stances on issues dealing with European integration, crime and terrorism as well as socioeconomic topics, such as welfare arrangements for the elderly (Vossen Citation2011).

Data and method

We make use of an extensive dataset combining three types of aggregate-level data sources: media data (independent variables), public opinion data (dependent variable) and real-world indicators (control variables).

News coverage

A dictionary-based automated content analysis was applied to assess the salience of immigration in the news, as well as its linkage with crime, terrorism and the economy. We selected three prominent Dutch newspapers: quality broadsheets de Volkskrant and NRC Handelsblad together with De Telegraaf, which is the most read popular newspaper of the Netherlands. These outlets attract a substantial share of all newspaper readers, and they make for a balanced newspaper selection: A left-leaning and right-leaning quality outlet and a right-leaning popular tabloid. Popular outlets have been found to report in more negative terms about immigration (e.g. Gabrielatos and Baker Citation2008). However, recent research provides evidence that actually both types of outlets contribute to certain – negative – stereotyping of immigrants (Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017): Tabloids by reproducing existing stereotypes, and broadsheets by creating and introducing new ones (KhosraviNik Citation2009). Although we do not include all immigration news available (e.g. online news, news items on radio or television and in other newspapers), we build on the assumption that newspaper coverage of a balanced set of national newspapers provides a good proxy for the general media landscape on the aggregate level.

Relying on data from September 2004 to December 2017, our analysis covers more than thirteen years of news coverage (N = 1,697,976 articles; N = 151,502 immigration articles). For each issue (immigration, crime, terrorism, economy), we developed a comprehensive search string on the basis of existing examples in the literature (e.g. Van Klingeren et al. Citation2014) and a process of fine-tuning through several rounds of pre-testing. For the immigration issue, we included the five largest immigrant groups in the Netherlands, therefore the selected news content also includes coverage concerning the integration of these (first-, second- and third-generation) immigrants into Dutch society, next to “hard” immigration news. For crime, we selected all news covering punishable acts according to Dutch criminal law, as to minimize bias that could result from selecting specific offenses (see also Appendix A).Footnote3

The immigration visibility score was calculated by dividing the monthly number of immigration articles by the total number of articles (×100), resulting in monthly visibility percentages. Working with relative measures is imperative, since the relative presence of issues indicates to the audience how important these issues are vis-a-vis other topics. In a similar fashion, variables were constructed that measure the (relative) visibility of crime news, terrorism news, and economic news. We conducted our analyses on a monthly level, since this is the lowest level for which all types of data – media, public opinion, real-world – were consistently available. Moreover, prior research shows that news coverage takes a while to be processed by the public (e.g. three to four weeks as found by Wanta and Hu Citation1994).

Subsequently, measurements were created indicating the visibility of crime, terrorism, and socio-economic issues within immigration news. For each combination (immigration and crime; immigration and terrorism; immigration and economy), monthly percentages were calculated by dividing the number of articles that contained references to the three issues by the total amount of immigration news items (×100; see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (monthly level).

Finally, we calculated the monthly percentages of immigration related news articles in which political parties were explicitly mentioned. In addition to the Freedom Party, these measures were also constructed for the Liberal Party, the Labor Party, and the Christian Democrats. These parties are, respectively, the largest right-wing (liberal), left-wing (social-democratic) and conservative (inspired by Christian values) party of the Netherlands during our time frame, which have attracted most votes throughout the years and all have been part of coalition governments during parts of the investigated period.

Public opinion data

The number of virtual parliamentary seats for the Freedom Party is the main dependent variable in this study. Our measurement is based on weekly polling data retrieved from Peil.nl, one of the most prominent polling agencies of the Netherlands used in academic longitudinal research (e.g. Vliegenthart and Van Aelst Citation2010). Each week, a panel of citizens were asked: “For which party would you vote if elections were to be held today?” resulting in a virtual distribution of 150 parliamentary seats. These data were converted into monthly polling scores. Over the years, Freedom Party popularity changed considerably. It started off with 11 seats, reached a peak of 41 seats in January 2016, and by December 2017 it would gain 14 seats in Parliament. To compare media effects across political parties, the same approach was adopted to measure monthly levels of electoral support for the Liberal Party, the Labor Party, and the Christian Democrats.

Real-world indicators

To examine the extent to which news leads to changes in anti-immigrant party support, we need to control for potentially confounding influences coming from real-world developments, which might provide an alternative explanation for the Freedom Party’s popularity.

We take immigration figures into account. Monthly immigration inflows are retrieved from the Dutch Bureau of Statistics (CBS). We also control for crime rates, which are operationalized as the total number of registered criminal offences by the police. Only yearly measures are available for the whole period (2004–2017), these are also retrieved from the Dutch Bureau of Statistics. In addition, we rely on data from the Global Terrorism Database (GTB) to control for terrorist activity. The GTB is a publicly available database providing information about terroristic activity throughout the world from 1970 until present. Terrorism is defined as the “threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.” We selected all (attempts of) terrorist attacks that took place in Western Europe and the US. Finally, national economic performance is measured by the Composite Leading Indicators (CLI) series developed by the OECD, which is a combined measure of several macroeconomic indicators, such as share prices and business climate indicators. CLI presents a dynamic measure of fluctuations in economic activity, and is used as proxy for general economic performance at the national level (see also Van Dalen, de Vreese, and Albaek Citation2015). Finally, to control for election times, a dummy was included indicating the months in which national election campaigns and national elections took place in the Netherlands.

Analysis

Time-series analyses are employed to analyze our data. As a first step, we use Vector Autoregression (VAR) analysis with differenced variables for reasons of stationarity (see below) to investigate the causal direction of the relationships. Results of Granger causality tests (one lag; i.e. one month) show that immigration news in the previous month significantly affects current levels of anti-immigrant party support, while controlling for lagged values of support (χ2 = 6.62, p = .010).Footnote4 However, levels of anti-immigrant party support do not significantly influence news coverage about the issue (χ2 = 0.07, p = .796).

Now that causal directions are clarified, ARIMA models are employed to analyze the data in further detail. Time-series analysis offers the unique opportunity to sort out time order, allowing for the determination of the causal ordering of the relationships between variables. ARIMA builds on the idea that in order to predict the current value of a time series variable, one should first consider the variable’s own past before adding any exogenous explanatory variables to the model. As a next step, the effects of lagged values of independent variables on current values of the dependent variable are estimated. Cross-correlation functions indicate models with one time lag are the best fitting ones. Dickey-Fuller tests are conducted to check whether the series meet the criterion of stationary (i.e. absence of trends in means and variances). The media variables, immigration figures, crime statistics and terrorist activity series are all stationary, however, Freedom Party support and CLI are not. Therefore, the latter two series need to be differenced, just like all other exogenous variables. Subsequent tests confirm that after differencing (Xt – Xt-1) all series meet the requirement of stationarity.

Autoregressive (AR) and/or moving average (MA) terms are to be added to achieve a model that fits the data best. AR-terms indicate the lagged endogenous variables (i.e. changes in poll scores at earlier time-points) that resemble the effects of previous values of the series on the current value; MA-terms represent the influence of residuals from previous values on the current value (Vasileiadou and Vliegenthart Citation2014, 697). Ljung Box’s Q statistics indicate a model including one AR-term (1,1,0). Both residuals and squared residuals resemble white noise, meaning that no issues of autocorrelation or heteroscedasticity bias our results: Residuals randomly fluctuate around zero and are evenly distributed over time.

Results

Explaining anti-immigrant party support

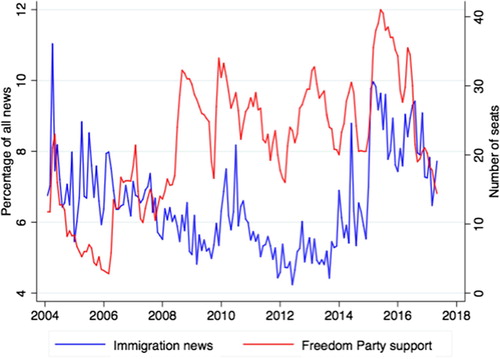

shows over-time trends in immigration news and Freedom Party support. From 2004 until the end of 2009, media attention for the issue gradually declines. After a short revival in 2010, it reaches its lowest point in February 2014 with only 3.82% of all articles referring to immigration. From then onwards and probably due to the refugee crisis, the visibility of immigration gradually grows until it peaks in January 2016 with 8.73% of all news dealing with immigration. Afterwards, a steep decrease sets in. Freedom Party support increases over time peaking in January 2016 with 41 seats in the polls (26% of all seats; #1 party in the polls), an extremely high score given the high fragmentation in the Dutch multiparty system. Although this coincides with a peak in immigration news in that same month, shows that both series do not strongly move in tandem, which is reflected in a Pearson correlation coefficient of r = 0.10 (p = .199).

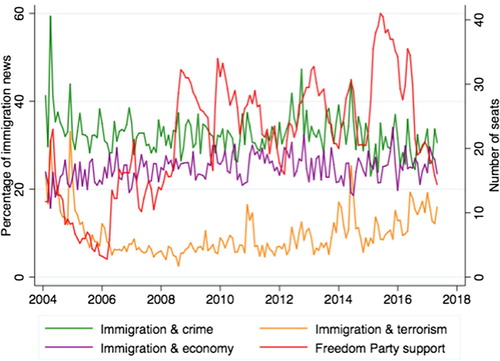

shows the over-time development of immigration news with references to the issues of crime, terrorism and the economy, expressed as the percentage of all immigration news. News that links immigration to crime occurs most frequently (M = 31.59%, SD = 4.46), followed by news associating immigration with economic issues (M = 24.80%, SD = 3.00), and immigration news referring to terrorism (M = 9.82%, SD = 5.05). The peak in November 2004 of immigration news with references to either crime or terrorism coincides with the murder of Dutch cineaste Theo van Gogh by Mohammed Bouyeri, a second-generation immigrant with Moroccan background. Both series (immigration and crime; immigration and terrorism) show roughly similar patterns over time, with a high responsiveness to key events like the Theo van Gogh murder, reflected in a correlation coefficient of r = 0.39 (p < .001). Immigration news in which the economy is mentioned shows a different and more stable pattern. No high peaks occur during key events, resulting in the lowest standard deviation of these series. The correlation coefficient with the immigration and crime series is r = −0.35 (p < .001), and with the immigration and terrorism series is r = −0.34 (p < .001), indicating opposing patterns over time. When news links immigration to economic issues, the focus is less on the criminal and terrorist attributes, and vice versa.

To explain changes in anti-immigrant party support, we adopt a stepwise approach in the construction of our models, starting with real-world figures as the independent variables.Footnote5 Model 1, hence, includes immigration inflows, crime rates, terrorist activity, economic performance, and election times. shows the results. None of the real-world variables significantly affect support for the Freedom Party, implying that support is not guided by real-world developments, such as number of immigrant inflows or economic trends. Interestingly, election times do have a significant and negative impact on levels of electoral support, suggesting that people tend to become more reluctant of expressing a voting preference for the Freedom Party when elections are actually approaching.

Table 2. Explaining differences (Δ) in anti-immigrant party support (2004–2017).

Model 2 adds news coverage to the equation. More specifically, we include measures of change in monthly percentages immigration news, crime news, terrorism news and economic news as predictors of anti-immigrant party support. The results show that only immigration news has a positive and significant impact on Freedom Party support (b = 0.73, SE = 0.23, p < .010), leading us to accept Hypothesis 1. No effect is found for other types of news: Neither of them yields a significant effect. This confirms the idea of anti-immigrant parties being single-issue parties, and showing how the salience of other topics is not that relevant to their success.

In Model 3, we add the three subcategories of immigration news to the analysis; the positive effect of general immigration news is still significant, although it becomes slightly weaker. None of the immigration news subcategories has a statistically significant impact, suggesting that it is not through the presence of certain “threatening” policy domains within immigration news that people become more supportive of Wilders. Accordingly, Hypothesis 3 is rejected.Footnote6 In the final model, we add Freedom Party visibility within immigration news to the equation and see that this variable does not make a difference either. The more the media report about immigration, the more seats Wilders’ Freedom Party gains, regardless of whether the party is explicitly mentioned in the news. Apparently, people do not need the media to associate the issue of immigration with the Freedom Party; based on these results we reject Hypothesis 5.

The impact of immigration news on support for other parties

Exploring the exclusiveness of immigration issue ownership, we examine the effects of immigration news on electoral support for other political parties as well. displays the results of the analyses, in which support for the Liberal Party (VVD), Labor Party (PvdA), and the Christian Democrats (CDA) serve as dependent variables.

Table 3. Explaining differences (Δ) in support for other political parties (2004–2017).

In each analysis, we first look at the impact of real-world developments together with general issue visibility (immigration, crime, terrorism, economy) while controlling for election times (Model 1). Then, we add the subcategories of immigration news to the analysis (Model 2). Finally, we explore the volatility of issue ownership by including party visibility in immigration news (Model 3).

First, we focus on support for the Liberal Party (VVD), which was the second ranked party regarding the immigration according to the Chapel Hill Expert Survey. Model 1 shows that none of the general news categories – immigration, crime, terrorism, economy – lead to any shifts in electoral support. When adding the subcategories of immigration news to the analysis, again no media effects are found. However, in Model 3, we find that party visibility in immigration news does have a positive and significant impact on (changes in) electoral support for the Liberal Party. In this most comprehensive model, we also see that general immigration news is negatively associated with support, although the effect is only marginally significant. These findings imply that when immigration becomes salient in the news, this is not necessarily beneficial for the Liberal Party. However, when the Liberal Party manages to be explicitly linked to the topic by the media, it does increase its electoral support. This finding speaks to earlier work on issue ownership stating that when the media repeatedly link a party to an issue, it is possible to “steal” issue ownership from the original owner (Walgrave and de Swert Citation2007). The positive effect of election times – robust across all models – indicates that people are more willing to support the Liberal Party in times of (upcoming) elections, while we saw that this specific context variable has a negative impact on Freedom Party support (). This implies that polls held further from election day may overestimate the actual vote share the PVV party would get, whereas for the VVD the polls may underestimate the actual share.

Next, focus on support for the Social Democrats, as organized in the Labor Party (PvdA). Again, the first two models show that media coverage has no effect. However, different from the Liberal Party, Model 3 indicates that Labor Party visibility in immigration news does not lead to more support. Apparently, the immigration issue is not associated with the Labor Party – neither positively nor negatively – and more news about immigration in which the Labor Party is mentioned does not make any difference for its electoral popularity.

Finally, the same procedure is adopted to predict support for the Christian Democrats (CDA). Model 1 and Model 2 indicate no media effects, and also the context of election times does not matter for electoral support. However, in Model 3, we see that party visibility – again – has an effect. While general immigration news does not have any significant impact on the electoral fortunes of the Christian Democrats, news in which the party is explicitly linked to the issue does make difference. However, in contrast to the Liberal Party, this association with the issue of immigration leads to lower levels of support. For the Christian Democrats, it is best not to be associated with immigration, as it comes at the expense of (virtual) votes. In sum, immigration news does not boost electoral support for the other political parties, which leads us to accept Hypothesis 2. Furthermore and similar to the results from , we conclude that no second-level agenda-setting effects are taking place here. Whether and to what extent immigration news contains references to crime, terrorism, or the economy, does not matter for the propensity to vote for the Liberals, the Social Democrats, or the Christian-Democrats. Therefore, also Hypothesis 4 is accepted.

Interesting are the results with regard to party visibility. The effects are not fully in line with our theoretical expectation that being linked to the immigration issue in the news would have beneficial electoral consequences for all parties. Only the Liberal Party reaps the benefits of this association, while for the Labor Party there is no effect and for the Christian Democrats the electoral consequences are even negative. Therefore, we reject Hypothesis 6.

Discussion

In line with previous research applying first-level agenda-setting theory and priming (e.g. Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2007; Dunaway, Branton, and Abrajano Citation2010; Pardos-Prado, Lancee, and Sagarzazu Citation2014), we find that a higher level of immigration visibility in the news has a strong and positive bearing on levels of anti-immigrant party support. No additional effects are found for immigration news containing references to crime, terrorism or the economy. One possible explanation could be that immigration news is – across the board – already negatively valenced (Meltzer et al. Citation2017; Eberl et al. Citation2018), and, as a consequence, not much room for additional media effects is left once subcategories emphasizing immigrants’ potential threats to society become even more present. The fact that news about crime, terrorism or the national economy (without being linked to the immigration issue) does not lead to higher (or lower) levels of anti-immigrant party support, also points to the genuine single-issue signature of the Freedom Party, at least in the eyes of citizens. These results validate the relevance of issue ownership theory indicating that anti-immigrant parties experience considerable electoral advantages when immigration is visible as a news topic, while other political parties do not benefit. Hence, anti-immigrant parties have a strong incentive to keep the immigration issue on the media agenda, especially in times of elections and electoral campaigns.

Party visibility within immigration news is not a necessary precondition for anti-immigrant parties to benefit from immigration news. This speaks to earlier work suggesting that stressing already-owned issues may not always have beneficial electoral consequences for parties, especially not when other issues are salient to the public and in the media (e.g. Kleinnijenhuis et al. Citation1995). At the same time, maintaining issue ownership is key, especially in the highly fragmented, multi-party context of the Netherlands. The main competitor of the Freedom Party on the right side of the political spectrum, the Liberal Party, is able to benefit from immigration news as well, as long as it is explicitly mentioned in it. This confirms the idea of Walgrave and de Swert (Citation2007) that issue ownership indeed can be transferred, although such a transmission is often temporarily and only applies to the “competence dimension” (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Nuytemans Citation2009). Nevertheless, for anti-immigrant parties, consistently drawing attention to its core issue and securing a durable association with it is important to enhance ownership. This is especially true in multiparty systems in which anti-immigrant parties are often in opposition while competitive parties hold the relevant ministerial posts (Walgrave, Tresch, and Lefevere Citation2015). The Liberal Party seems to be aware of the electoral potentials as it has continuously tried to link itself to the immigration issue by repeatedly bringing up new proposals for (stricter) policies.

In contrast to the Liberal Party, the Christian Democrats experience negative electoral consequences when being visible in immigration news, while the linkage has no consequences for the Labor Party. This raises interesting questions related to the preconditions of issue ownership competition. For all parties (except for the Freedom Party) holds that they delivered Ministers that were responsible for immigration and integration processes during parts of the investigated time frame. Such a responsibility provides an opportunity to conquer issue ownership, at least in terms of perceived competence. However, the results are strikingly different across the parties. One possible explanation could be that the Christian Democrats delivered the minister of immigration (2010–2012) in a minority cabinet supported by the Freedom Party. In this – heavily criticized – political collaboration, the Christian Democrats were not able to set their own immigration policies but were largely constrained by the preferences of the Freedom Party, which might explain why they also could not gain ownership on the issue in terms of competence. Moreover, the immigration issue has repeatedly caused major clashes within the Christian Democratic party about which direction (i.e. harsher versus softer) the party should take. Rather than being the “issue owner,” this party may be perceived as being especially incapable of dealing with immigration policies. It would be an interesting avenue for future research to further analyze these inter-party differences.

Surprisingly, none of the real world trends – immigration inflows, crime rates, terrorist activity, national economic conditions – had any impact on political support. The absence of these effects underscores the pivotal role the media play in the formation of people’s political preferences: Not objective conditions matter, but rather information about these conditions as conveyed by the news media.

Our study has some limitations. First of all, we do not measure issue ownership directly. This restricts us to hypothesizing about the mechanisms at play, and the role of different issue ownership dimensions. It would be interesting to expand our analyses with public opinion data in which it is possible to disentangle the competence and associative issue ownership dimensions. Second, relying on a large-scale computer-assisted content analysis of news coverage allows for the analysis of a large number of news items. At the same time, this methodological approach cannot compete with the accuracy of human coders when it comes to the understanding of textual meaning (Grimmer and Stewart Citation2013). Furthermore, we did not measure the valence of the news content, which could at least partly explain the absence of second-level agenda-setting effects, since immigration news already tends to be negatively valenced on itself (e.g. Jacobs, Meeusen, & D’Haenens, 2016). It would be interesting to complement our analyses with a sentiment analysis and examine whether and to what extent the tone of immigration news has additional explanatory power. Furthermore, taking into account immigration sub-issues with more positive or human connotations (e.g. human rights) might increase our understanding of related news effects. Finally, it remains an open question whether we would find the same effects for other issues and other parties. Applying the same analyses to – for example – the environment issue and the Green Party would allow us to investigate the generalizability of our results.

In sum, the salience of the immigration issue in the news is beneficial for anti-immigrant parties, but might also boost the electoral successes of its competitors, if they manage to be linked to the issue. These results suggest that issue ownership is not a given fact, but a political asset that requires maintenance. The differential media effects of party visibility call for further research assessing the robustness of these findings and laying bare the mechanisms at play. In times in which anti-immigrant parties are celebrating electoral successes throughout the Western world, it is of the greatest relevance, both in academic and societal terms, to grasp the sources of their success. With this study we hope to contribute and to provide a fruitful point of departure for future research.

Suplemental_file.docx

Download MS Word (115.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alyt Damstra

Alyt Damstra (M.A. Political Science, University of Amsterdam, 2015) is a PhD candidate at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on the formation and effects of economic/financial news as well as on the impact of immigration news.

Laura Jacobs

Laura Jacobs (PhD Social Sciences, KU Leuven, 2017) is a post-doctoral researcher at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam. Her research focuses on the content and effects of immigration news, hate speech, and media effects in general.

Mark Boukes

Mark Boukes (PhD Communication Science, University of Amsterdam, 2015) is an Assistant Professor at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam. His research interest is in the coverage and effects of economic news; moreover, he has been working on the topic of infotainment with a specific focus on political satire.

Rens Vliegenthart

Rens Vliegenthart (PhD Political Communication, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 2007) is a Full Professor in Media and Society, at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam. His broad research agenda includes media coverage of political actors, social movements and economic processes and the subsequent impact of this coverage on public opinion and political decision-making.

Notes

1 See for more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/our-surveys/.

2 See for more information: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/.

3 A manual analysis of a random subset of immigration news articles shows that in a majority of the newspaper articles (79.3%), immigration was indeed (one of) the main topic(s).

4 Results of the VAR analyses are available upon request.

5 All models were carefully controlled for issues of multicollinearity. The variables terrorism news and immigration & terrorism news were highly correlated (r = .85), as well as the variables crime news and immigration & crime news (r = 69). Additional analyses in which each of these correlating variables was included separately yielded the same results as the ones presented in and .

6 When these subcategories are operationalized as percentages of all news per month, the results were identical (also for the analyses in ).

References

- Aalberg, Toril, and Anders T. Jenssen. 2007. “Do Television Debates in Multiparty Systems Affect Viewers? A Quasi-Experimental Study with First-Time Voters.” Scandinavian Political Studies 30 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00175.x.

- Ansolabehere, Stephen, and Shanto Iyengar. 1994. “Riding the Wave and Claiming Ownership Over Issues: The Joint Effects of Advertising and News Coverage in Campaigns.” Public Opinion Quarterly 58: 335–357. doi:10.1086/269431.

- Atwell Seate, Anita, and Dana Mastro. 2016. “Media’s Influence on Immigration Attitudes: An Intergroup Threat Theory Approach.” Communication Monographs 83 (2): 194–213. doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1068433.

- Bobo, Lawrence. 1983. “Whites’ Opposition to Busing: Symbolic Racism or Realistic Group Conflict?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45 (6): 1196–1210. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.6.1196.

- Boomgaarden, Hajo G., and Rens Vliegenthart. 2007. “Explaining the Rise of Anti-immigrant Parties: The Role of News Media Content.” Electoral Studies 26 (2): 404–417. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2006.10.018.

- Boomgaarden, Hajo G., and Rens Vliegenthart. 2009. “How News Content Influences Anti-immigration Attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005.” European Journal of Political Research 48 (4): 516–542. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01831.x.

- Bos, Linda, and Wouter van der Brug. 2010. “Public Images of Anti-immigration Parties: Perceptions of Legitimacy and Effectiveness.” Party Politics 16 (6): 777–799. doi:10.1177/1354068809346004.

- Budge, Ian, and Dennis J. Farlie. 1983. Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-three Democracies. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Burscher, Bjorn, Joost van Spanje, and Claes de Vreese. 2015. “Owning the Issues of Crime and Immigration: The Relation between Immigration and Crime News and Anti-immigrant Voting in 11 Countries.” Electoral Studies 38: 59–69. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2015.03.001.

- Caviedes, Alexander. 2015. “An Emerging ‘European’ News Portrayal of Immigration?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (6): 897–917. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.1002199.

- Dinas, Elias, and Joost van Spanje. 2011. “Crime Story: The Role of Crime and Immigration in the Anti-immigration Vote.” Electoral Studies 30 (4): 658–671. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2011.06.010.

- Dixon, Travis L., and Charlotte L. Williams. 2015. “The Changing Misrepresentation of Race and Crime on Network and Cable News.” Journal of Communication 65 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1111/jcom.12133.

- Dunaway, Johanna, Regina P. Branton, and Marisa A. Abrajano. 2010. “Agenda-setting, Public Opinion, and the Issue of Immigration Reform.” Social Science Quarterly 91 (2): 359–378. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00697.x.

- Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Christine E. Meltzer, Tobias Heidenreich, Beatrice Herrero, Nora Theorin, Fabienne Lind, Rosa Berganza, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Christian Scheme, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2018. “The European Media Discourse on Immigration and its Effects: A Literature Review.” Annals of the International Communication Association 42 (3): 207–223. doi:10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452.

- Esses, Victoria M., Lynne M. Jackson, and Tamara L. Armstrong. 1998. “Intergroup Competition and Attitudes toward Immigrants and Immigration: An Instrumental Model of Group Conflict.” Journal of Social Issues 54 (4): 699–724. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01244.x.

- Gabrielatos, Costas, and Paul Baker. 2008. “Fleeing, Sneaking, Flooding: A Corpus Analysis of Discursive Constructions of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press, 1996–2005.” Journal of English Linguistics 36 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1177/0075424207311247.

- Geers, Sabine, and Linda Bos. 2017. “Priming Issues, Party Visibility, and Party Evaluations: The Impact on Vote Switching.” Political Communication 34 (3): 344–366. doi:10.1080/10584609.2016.1201179.

- Green, Jane, and Sara B. Hobolt. 2008. “Owning the Issue Agenda: Party Strategies and Vote Choices in British Elections.” Electoral Studies 27 (3): 460–476. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2008.02.003.

- Greussing, Esther, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2017. “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1749–1774. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1282813.

- Grimmer, Justin, and Brandon M. Stewart. 2013. “Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts.” Political Analysis 21 (3): 267–297. doi:10.1093/pan/mps028.

- Hopmann, D. N., R. Vliegenthart, C. De Vreese, and E. Albæk. 2010. “Effects of Election News Coverage: How Visibility and Tone Influence Party Choice.” Political Communication 27 (4): 389–405. doi:10.1080/10584609.2010.516798.

- Iyengar, Shanto, and Donald R. Kinder. 1987. News that Matters: Television and American Opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- KhosraviNik, Majid. 2009. “The Representation of Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Immigrants in British Newspapers during the Balkan Conflict (1999) and the British General Election (2005).” Discourse and Society 20 (4): 477–498. doi:10.1177/0957926509104024.

- Kleinnijenhuis, Jan, Dirk J. Oegema, Jan de Ridder, and Herman Bos. 1995. De democratie op drift. Amsterdam: VU-Uitgeverij.

- Kleinnijenhuis, Jan, and Annemarie S. Walter. 2014. “News, Discussion, and Associative Issue Ownership: Instability at the Micro Level versus Stability at the Macro Level.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 19 (2): 226–245. doi:10.1177/1940161213520043.

- McCombs, Maxwell E., and Donald L. Shaw. 1972. “The Agenda-setting Function of Mass Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1075/asj.1.2.02mcc doi: 10.1086/267990

- McLaren, Lauren, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2017. “News Coverage and Public Concern about Immigration in Britain.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research, edw033. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edw033.

- McLaren, Lauren, and Mark Johnson. 2007. “Resources, Group Conflict and Symbols: Explaining Anti-immigration Hostility in Britain.” Political Studies 55 (4): 709–732. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00680.x.

- Meltzer, Christine E., Christian Schemer, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Nora Theorin, and Tobias Heidenreich. 2017. Media Effects on Attitudes toward Migration and Mobility in the EU: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Mainz: Compas/Reminder.

- Mudde, Cas. 1999. “The Single-issue Party Thesis: Extreme Right Parties and the Immigration Issue.” West European Politics 22 (3): 182–197. doi:10.1080/01402389908425321.

- Mudde, Cas. 2013. “The 2012 Stein Rokkan Lecture. Three Decades of Populist Radical Right Parties in Western Europe: So What?” European Journal of Political Research 52 (1): 119–141. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02064.x doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02065.x

- Pardos-Prado, Sergi, Bram Lancee, and Inaki Sagarzazu. 2014. “Immigration and Electoral Change in Mainstream Political Space.” Political Behavior 36 (4): 847–875. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9248-y.

- Petrocik, John, R. 1996. “Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study.” American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 825–850. doi:10.2307/2111797.

- Quinsaat, Sharon. 2014. “Competing News Frames and Hegemonic Discourses in the Construction of Contemporary Immigration and Immigrants in the United States.” Mass Communication and Society 17 (4): 573–596. doi:10.1080/15205436.2013.816742.

- Scheufele, Dietram A., and David Tewksbury. 2007. “Framing, Agenda-setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models.” Journal of Communication 57 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00337.x.

- Sheets, Penny, Linda Bos, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2016. “Media Cues and Citizen Support for Right-wing Populist Parties.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 28 (3): 307–330. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edv014.

- Sherif, Carolyn W., and Muzafer Sherif. 1967. “Attitudes as the Individual’s Own Categories: The Social Judgement Approach to Attitude Change.” In New Attitude, Ego Involvement, and Change, edited by Carolyn W. Sherif, and Muzafer Sherif, 105–139. York: Wiley.

- Stephan, Walter, G. Oscar Ybarra, and K. Rios Morrison. 2009. “Intergroup Threat Theory.” In Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, edited by Todd D. Nelson, 43–59. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Van Aelst, Peter, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2011. “Minimal or Massive? The Political Agenda-setting Power of the Mass Media According to Different Methods.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 (3): 295–313. doi:10.1177/1940161211406727.

- Van Dalen, Arjen, Claes H. de Vreese, and Erik Albaek. 2015. “Economic News through the Magnifying Glass: How the Media Cover Economic Boom and Bust.” Journalism Studies 18 (7): 890–909. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2015.1089183.

- Van der Linden, Meta, and Laura Jacobs. 2016. “The Impact of Cultural, Economic, and Safety Issues in Flemish Television News Coverage (2003–13) of North African Immigrants on Perceptions of Intergroup Threat.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (15): 2823–2841. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1229492.

- Van Klingeren, Marijn, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Rens Vliegenthart, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2014. “Real World is not Enough: The Media as an Additional Source of Negative Attitudes toward Immigration, Comparing Denmark and the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 31 (3): 268–283. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu089.

- Vasileiadou, Eleftheria, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2014. “Studying Dynamic Social Processes with ARIMA Modeling.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 17 (6): 693–708. doi:10.1080/13645579.2013.816257.

- Vliegenthart, Rens, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2007. “Real-world Indicators and the Coverage of Immigration and the Integration of Minorities in Dutch Newspapers.” European Journal of Communication 22 (3): 293–314. doi:10.1177/0267323107079676.

- Vliegenthart, Rens, and Peter Van Aelst. 2010. “Dutch and Flemish Political Parties in Newspapers and Polls: A Reciprocal Relationship.” Tijdschrift Voor Communicatiewetenschap 38 (4): 338.

- Vossen, Koen. 2009. “Hoe Populistisch zijn Geert Wilders en Rita Verdonk?” Res Publica (Liverpool, England) 51 (4): 437–465. doi: 10.5553/RP/048647002009051004001

- Vossen, Koen. 2010. “Populism in the Netherlands after Fortuyn: Rita Verdonk and Geert Wilders Compared.” Perspectives on European Politics and Society 11 (1): 22–38. doi:10.1080/15705850903553521.

- Vossen, Koen. 2011. “Classifying Wilders: the Ideological Development of Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom.” Politics 31 (3): 179–189. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2011.01417.x.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Knut de Swert. 2004. “The Making of the (Issues of the) VlaamsBlok.” Political Communication 21 (4): 479–450. doi:10.1080/10584600490522743.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Knut de Swert. 2007. “Where does Issue Ownership Come from? From the Party or from the Media? Issue-party Identifications in Belgium, 1991–2005.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 12 (1): 37–67. doi:10.1177/1081180X06297572.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Jonas Lefevere, and Michiel Nuytemans. 2009. “Issue Ownership Stability and Change: How Political Parties Claim and Maintain Issues through Media Appearances.” Political Communication 26 (2): 153–172. doi:10.1080/10584600902850718.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Jonas Lefevere, and Anke Tresch. 2012. “The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (4): 771–782. doi:10.1093/poq/nfs023.

- Walgrave, Stefaan, Anke Tresch, and Jonas Lefevere. 2015. “The Conceptualisation and Measurement of Issue Ownership.” West European Politics 38 (4): 778–796. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1039381.

- Wanta, Wayne, and Yu-Wei Hu. 1994. “Time-lag Differences in the Agenda-setting Process: An Examination of Five News Media.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 6 (3): 225–240. doi:10.1093/ijpor/6.3.225.