ABSTRACT

The Climate Strike Movement (or Fridays for Future) is one of the most prominent transnational protest movements nowadays. In this paper, I examine the reactions of politicians to this movement to answer the research question: To what extent have German Members of Parliament (MPs) been responsive to local environmentalist street protests by focusing their attention on the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policy? To this end, I apply dictionary-based quantitative text-analytical tools to study German MPs’ political communication through 292,949 Facebook posts and 43,644 parliamentary debates between September 2017 and February 2020. Focussing on the effect of the first global climate strike in March 2019 and leveraging varying protest frequencies between the electoral districts, I show that MPs are responsive to protest events in their districts. More local street protest events in an electoral district led to more attention to the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policies by political representatives associated with that district. Comparing different discursive arenas, I show how politicians adjust their communication according to the arena’s audience, with protests affecting the political attention to environmental policies more in parliamentary debates than on social media.

Introduction

“How dare you continue to look away and come here saying that you’re doing enough, when the politics and solutions needed are still nowhere in sight?” – Greta Thunberg, United Nations Climate Action Summit (23 September 2019)

Whether street protest activities affect political decision-making is one of the leading research questions in the social movement literature. While some studies focus on entire parliaments (e.g. Fassiotto and Soule Citation2017), others address party reactions (e.g. Borbáth and Hutter Citation2021; Hutter and Vliegenthart Citation2018; Wouters, Sevenans, and Vliegenthart Citation2021), or individual MPs’ responsiveness (e.g. Gause Citation2022; Wouters and Walgrave Citation2017). Here, I follow the approach of focusing on individual politicians as an analytical unit.

In their seminal paper, Wouters and Walgrave (Citation2017) show that protest affects MPs’ salience perception, position-taking, and decision to take action. Testing Tilly’s four criteria for successful social movements worthiness, unity, numerical strength and commitment (Tarrow and Tilly Citation2009) in an experimental setting, the authors find that MPs respond to protest that are big (numerical strength) and appear united (unity). Applying empirically tested formal models, Gause (Citation2022) finds that politicians are more likely to support protests by low-resource groups. For them, protesting is more costly and signals, thus, more salient concerns. In this paper, I add to this literature by emphasizing the protest location as a crucial factor for politicians to respond to protest.

Consequently, this paper contributes to the questions of whether protest activities have the power to initiate political change (e.g, Bernardi, Bischof, and Wouters Citation2021; Fassiotto and Soule Citation2017; Walgrave and Vliegenthart Citation2012; Wasow Citation2020; Wouters and Walgrave Citation2017) and how politicians respond to protests (e.g. Hutter and Vliegenthart Citation2018; Steinhardt Citation2017). Protests and the social movements associated with them cannot decide on policies directly. Political scientists often consider them “beggars at the policy gate” (Bernardi, Bischof, and Wouters Citation2021, 293). However, even following this perspective, social movements have the power to set the agenda, thus changing the political discourse of elites through their protest activities (Walgrave and Vliegenthart Citation2012). Social movements might change political discourses, which is the first step to initiate policy changes in the medium and long term. Protest sends public opinion signals to political representatives, who can then decide how to respond. Beyond protest research, I therefore also draw on the literature on (rhetorical) responsiveness (e.g. Bowler Citation2017; Hobolt and Klemmensen Citation2008; Pitkin Citation1967; Powell Citation2004) and dyadic representation in mixed-member electoral systems (Baumann, Debus, and Klingelhöfer Citation2017; Manow Citation2013; Zittel Citation2018; Zittel, Nyhuis, and Baumann Citation2019).

To answer the research question, I apply dictionary-based quantitative text-analytical tools to study German MPs’ political communication through 292,949 Facebook posts and 43,644 parliamentary debates between September 2017 and February 2020. I show that MPs are responsive to protest events in their districts by focusing on the effect of the first global climate strike (15 March 2019) and leveraging varying protest frequencies between the 299 German electoral districts.

My analysis indicates that local protest events in an electoral district during the first global climate strike day affected the political communication of the MPs representing this district. The MPs confronted with more protest events devoted greater attention towards the Climate Strike Movement on Facebook as well as in parliamentary debates and engaged more actively in parliamentary debates on Environmental Policy during and after protests. These results corroborate the importance of local protests and exemplify how MPs are responsive to street protests as public opinion cues.

Theory

Rhetorical responsiveness and dyadic representation

Scholars of representative democracies regard responsiveness as a crucial element of and an essential indicator for the quality of democratic representation. “Democratic representation means that the actions of […] policy makers are supposed to be responsive to the wishes of the people” (Powell Citation2004, 273). Accordingly, political responsiveness describes to what extent representatives are reactive to changes in citizens’ opinions (e.g. Pitkin Citation1967, 57). This paper focuses on the politicians’ communication and is therefore interested in what Hobolt and Klemmensen (Citation2008) conceptualize as rhetorical responsiveness.Footnote2 This concept describes how political actors change their attention to a specific issue in response to (changes in) public opinion. While some might argue that MPs’ communication is often just cheap talk, I consider it the first step towards substantial policy change. Voters evaluate the communication of political representatives for their electoral choices (Martin and Vanberg Citation2008), and hold them electorally accountable for what they say. Hence, being rhetorically responsive is vital for MPs to secure their (re-)election. Yet, the extent to which rhetorical responsiveness is present in a polity depends on its electoral system (Powell Citation2004), with majoritarian elements in electoral systems leading to more rhetorical responsiveness to geographic constituents (Schürmann Citation2023).

In the literature, the linking of district preferences with district representatives falls under the label of dyadic representation. In this portrayal, the district representative is described as an agent with the electorate as principal (Miller and Stokes Citation1963; Powell Citation2004). However, it might be difficult for representatives to execute their constituents’ preferences because these preferences are often unformed or at least unformulated (Pitkin Citation1967).

Street protest as public opinion signal

So, how can citizens draw the attention of representatives to a particular issue? Citizens have several ways to make their preferences known to their MPs, such as contacting them via mail, telephone, or personally. However, another effective way to attract the attention of politicians is street protest (Wouters, Staes, and Van Aelst Citation2022).

Street protest is crucial in politicizing issues and can serve as an agenda-setter (Hutter, Grande, and Kriesi Citation2016). Research shows that the effect of protest on legislative politics is strongest in the early stages of the agenda-setting process (King, Bentele, and Soule Citation2007; McAdam and Su Citation2002) and for particular policy areas such as social welfare spending where it amplifies public opinion shifts (Bernardi, Bischof, and Wouters Citation2021). In this context, street protest is successful in winning public support (Wouters Citation2019), with local protests successfully affecting the political attitudes and public opinion of residents of a particular geographic area (Wallace, Zepeda-Millán, and Jones-Correa Citation2014).

How politicians learn about protests in their districts

From a strategic point of view, politicians would be well advised to respond to protests within their districts. Yet, how do they learn about the protests that take place? First, politicians can learn about protests directly from the organizers. Protests usually do not happen spontaneously but are planned by civil society actors. These actors often have strong connections to political parties or politicians themselves (Hutter, Kriesi, and Lorenzini Citation2018). As protests aim to raise political attention, they directly inform politicians and even invite them to participate.

Second, politicians can be indirectly informed about protests. In this case, the media is the most important mediator. As protest activities aim to raise public attention, they depend on newspapers to make their activities known (Wasow Citation2020). And given the “media’s interest in spectacle” (Gamson and Wolfsfeld Citation1993, 125), protest activists have a comparatively easy job in convincing the media to report on their activities. Besides simple messages that are easy to convey to the newspaper’s audience, protests often also provide a visual spectacle which helps raise the media’s attention. Particularly local newspapers cover protest activities within their geographical vicinity (Kilgo and Harlow Citation2019). Politicians try to stay in touch with activities in their districts (Coffé Citation2018), for instance, by reading local newspapers.

In this context, mediated information about protests successfully persuades political representatives, with larger and united protests being most persuasive to politicians (Wouters and Walgrave Citation2017). Furthermore, not all MPs respond similarly; members of left-wing parties and opposition parties respond more frequently to protest (Hutter and Vliegenthart Citation2018; Wouters, Staes, and Van Aelst Citation2022). Also, district characteristics are crucial to consider, with most protests happening in capitals or major cities (Wüest and Lorenzini Citation2020). Finally, public opinion in the district is essential to consider, with protests often amplifying already existing preferences of the constituents (Bernardi, Bischof, and Wouters Citation2021).

The unique “Think Global, Act Local” protest approach of the Climate Strike Movement

The Climate Strike Movement (or Fridays for Future) is an interesting case in this context since it implemented a distinctive “think global, act local” protest approach. Most social movements focus their protest activities on major cities, especially capitals (Kriesi et al. Citation2020). However, members of the Climate Strike Movement emphasize the local dimension of climate politics and adjust their protest behaviour accordingly. As the Climate Strike Movement protests primarily consist of school kids with fewer resources for travelling to distant protest events, this approach stems from ideological and practical reasons (Sommer et al. Citation2020). As a result, climate strike protests occurred not only in capital cities such as Berlin or Paris but also in small villages in Bavaria or Brittany.Footnote3

To assess the extent to which MPs are rhetorically responsive to the protest events, I focus on the increase of salience they attribute to the Climate Strike Movement, and Environmental Policy. Given that the environment is a valence issue in most countries, the relevant variation comes from salience (Franzmann, Giebler, and Poguntke Citation2020). Hence, I test the following hypotheses:

H1a: MPs with more environmentalist protest events in their electoral districts refer afterwards more often to the Climate Strike Movement than MPs with fewer protests in their districts.

H1b: MPs with more environmentalist protest events in their electoral districts refer afterwards more often to Environmental Policy than MPs with fewer protests in their districts.

Social media as a means to individualize political communication

Politicians use different communication channels for different purposes (Castanho Silva and Proksch Citation2022). Arguably the most meaningful communicative action of MPs takes place in parliamentary debates. New policy proposals are discussed in parliamentary debates, and laws are finally adopted. Previous research illustrates how events outside the parliament affect the time MPs spend discussing a specific issue related to this event (Rauh Citation2015). Yet, speaking time in the plenary is not just the individual MP’s decision. Parties wield strong institutional power in assigning who speaks in parliamentary debates, with party leaders, for example, speaking more frequently than other MPs (Proksch and Slapin Citation2015, 85). Nevertheless, MPs can freely decide on the actual content of their speeches, which I expect them to do partially in response to activities by their geographic constituents.

The growing use of social media is probably the most important recent development that has profoundly changed politicians’ communication behaviour. Regarding online political communication, Facebook is the most prominent social media platform that allows MPs to communicate directly with their constituents as well as other economic, societal, or political elites. Unlike traditional media such as newspapers, no gatekeepers are present, and MPs can broadcast their message “without the distorting effect of journalists” (Karlsen Citation2011). In contrast to parliamentary debates, where the opportunity to speak is not equally accessible for every MP, every politician can deliberately decide the frequency and the content of their posts on social media. Therefore, MPs can use social media to circumvent the institutional constraints of parliamentary debates, such as limited speaking time.

Furthermore, some parties might want to avoid raising the profile of the Climate Strike Movement because they are not the issue owners. However, even MPs of these parties might want to talk about the Climate Strike Movement or Environmental Policy to appear responsive to their protesting geographic constituents. These MPs can then use social media to signal to their constituents that they care about the movement (Castanho Silva and Proksch Citation2022). Given the higher degree of independence that MPs enjoy on Facebook and the increased use for voter communication, I expect the following:

H2: The effect of local environmentalist street protests on MP communication is stronger on Facebook than in parliamentary debates.

Research design

Case selection: Germany

To test the hypotheses, I analyse the political communication of German MPs for three main reasons. Firstly, Germany’s parliamentary system emphasizes the importance of MPs as crucial actors in the legislative process. In contrast, for example to the USA, where the president exercises a comparatively large share of the power, the German parliament has a paramount position. As the formal legislature, the German parliament has the authority to change laws, as well as the power to elect the chancellor as head of government. In sum, MPs wield considerable power in the German parliamentary system.

Secondly, the German electoral system provides two ways to obtain a seat in parliament. While some MPs are elected in single-seat districts, others are elected via party lists (Schürmann and Stier Citation2023). Nearly all sitting MPs ran simultaneously for a list and a nominal mandate, thus participating in the plurality contest (Manow Citation2013). Politicians have to monitor public opinion carefully to achieve the goal of staying in office (Downs Citation1957). This plurality contest in the German mixed-member electoral system thus incentivizes MPs to align their political behaviour with the existing preferences in their districts (Baumann, Debus, and Klingelhöfer Citation2017).

Thirdly, as in other Western European countries, legislative behaviour in Germany is still party-dominated, in contrast to, for example, the US-American system in which legislators rather represent geographic districts (Zittel, Nyhuis, and Baumann Citation2019). This party-dominated nature makes it a less-like case compared to first-past-the-post systems where representatives have geographic constituents as their primary principals. Therefore, if local protests affect representatives’ communicative behaviour in the German party-dominated system, the effects should be stronger in systems where parties play a less dominant role, such as in the US-American system.

Data: political communication on Facebook and in parliamentary speeches

I obtained the Facebook posts from the “Social Media Monitoring for the German federal election 2017” (Stier et al. Citation2018a) data set. While the data set was initially created for the German federal election campaigning period in 2017, it goes beyond the German Federal Election date. Facebook posts are retrieved via the CrowdTangle API, which provides historical Facebook data of all public Facebook pages. The social media data set consists of 292,949 Facebook posts between 25 September 2017 (the first day of the new legislative period) and 20 February 2020. The research period ends here because, after this date, COVID-19 became the major political topic. In this context, Fridays for Future Germany decided to suspend protest events due to the pandemic.

The second data I use are parliamentary debates. An extended version of the ParlSpeech data set is the source for the German Bundestag’s parliamentary debates (Rauh and Schwalbach Citation2020). The data set contains the parliamentary debates of the 19th legislative period of the German parliament, starting in September 2017 until the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020, with an absolute number of 43,644 speeches.

My primary analysis covers a subset of this time frame starting immediately after the first global climate strike day (15 March 2019) until the second global climate strike day (24 May 2019). The research period ends before the second global climate strike day, so the MPs’ rhetorical responsiveness is not affected by these new protest events.

Method: dictionary-based quantitative text analysis

To answer the research question, I conduct regression analyses based on a dictionary-based quantitative text analysisFootnote4 evaluating the MPs’ political communication.Footnote5 The social media posts and parliamentary speeches are assessed to determine whether they refer to the Climate Strike Movement. For this purpose, I have created a dictionary that lists all terms related to the Climate Strike Movement. On the one hand, the dictionary consists of important buzzwords that people use to show support for the Climate Strike Movement. On the other hand, the names of the most prominent leaders of the movement and the names of essential organizations are part of the dictionary. Beyond that, the most important hashtags related to the Climate Strike Movement are also part of the dictionary. The first column of presents exemplary entries of the Climate Strike Movement dictionary. Especially on social media platforms, German politicians frequently use German and English terms. Hence, terms in both languages are part of the dictionary.Footnote6

Table 1. Dictionary examples.

Besides the issue attention towards the Climate Strike Movement, I also analyse whether the MPs differ in their substantial issue attention towards environmental topics. This substantial issue attention is assessed with a dictionary-based quantitative text analysis applying the European Union’s EuroVoc dictionary. Initially, the EuroVoc dictionary was created to facilitate the translation of essential keywords in different policy fields (European Union Citation2015). However, the availability of validated translations in all official European Union (EU) languages makes the EuroVoc dictionary extremely useful for comparative text analysis. Given the focus on different policy areas, this dictionary is especially useful for political scientists.

Moreover, the EuroVoc dictionary was already successfully validated and applied to the agenda-setting power of social movements in Belgium (Walgrave and Vliegenthart Citation2012). For my analyses, I apply the section “Environmental Policy,” entailing terms like environmental tax or emission trading, which directly relate to policies and are most interesting for assessing politicians’ rhetorical responsiveness towards environmental issues. The second column of present exemplary entries of the dictionary.Footnote7

This textual data constitutes the basis for creating the dependent variable for the regression analyses. It is the number of explicit references of Climate Strike Movement (or Environmental Policy) terms by an MP, which I separately count for the social media platforms and the parliamentary speeches. Each MP represents a single observation, and the individual MP’s number of explicit references to the Climate Strike Movement is the variable that I aim to explain with the multivariate regression analysis. Since the count distribution is overdispersed with an approximately linear mean-variance relation, I apply a quasi-poisson distribution (Ver Hoef and Boveng Citation2007). The absolute number of social media posts/speeches given by an MP is integrated into the model to control for the factor that some MPs are more frequently active on social media or in parliamentary debates. Appendices A2 and A3 present detailed explanations of the operationalization and descriptive statistics of the independent and control variables.

My primary analysis focuses on how local protests in electoral districts have affected the political discourse of MPs associated with these districts. Nearly all MPs simultaneously ran for a direct mandate and a list mandate (dual candidacy). For these MPs, the associated district is where they ran for a direct mandate, regardless of whether they won it. The few MPs who had been list-candidates only (22/709) are associated with the district where they have their official MP office.

The primary independent variable is the number of protest events during the first global climate strike in March 2019. Fridays for Future Germany has provided me with data on the exact locations of climate strike protests during the first global climate strike day. Unfortunately, the number of protest participants per event is not available.

Since I am interested in the immediate effect of the first global climate strike day on 15 March 2019 on the Environmental Policy debate, I analyse the period immediately after the first global climate strike day until the second global climate strike day (24 May 2019). Finally, I add the MPs’ communication about the Climate Strike Movement (or Environmental Policy) before the protest event as a control variable. This variable controls the MPs’ attention on the Climate Strike Movement (or Environmental Policy) before the actual protest event. Thus, the inclusion of this variable allows to identify whether MPs confronted with more protests in their districts increased their attention to the climate (protest) issue more than those faced with fewer protests. Beyond that, I control for personal characteristics of the MP (Gender, Age, Parenthood status, Doctoral degree), party characteristics (Opposition status, Environmental Protection, Human Rights) or alternatively, party membership and district-related control variables (Nominally elected, Share of young population, Education level, the Average income of private households, Public opinion: climate protection).

Results

Rhetorical responsiveness to local protests events

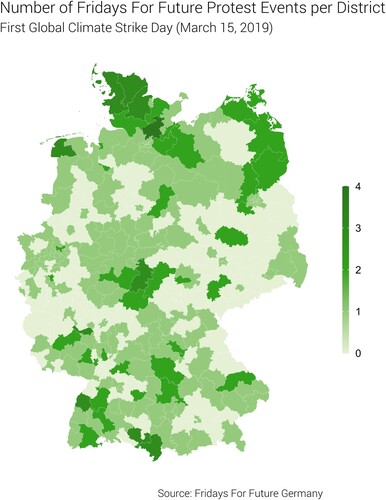

shows the absolute number of Friday for Future protests per district during the first global climate strike day in March 2019. Two points stand out: Firstly, there were more protests per constituency in coastal areas than in other German regions. A reason for this could be the higher vulnerability of coastal areas to climate change (Roukounis and Tsihrintzis Citation2022). Secondly, there are very few protest events in the southern districts of Eastern Germany.

Table 2. Absolute number of dictionary terms mentions and percentage of MPs using these terms.

Turning to the MPs’ rhetorical responsiveness to these protests (see ), I next explore the effect of the protest events on the substantial attention of German MPs towards the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policy. To this end, I assess the MPs’ political communication during and immediately after the first global climate strike (15 March 2019) until the second global climate strike (24 May 2019). First, I look closely at how many MPs engaged with the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policy. While 74 MPs (10.8%) referred 277 times to the Climate Strike Movement on Facebook before the first global climate strike took place, 177 (25.8%) referred 605 times to the movement between the first and second Global Climate Strike. 98 MPs (14.8%) referred 165 times to Environmental Policy before the first climate strike, whereas 137 MPs (20%) referred 303 times to it after the protest. In parliamentary debates, the absolute number of MPs who referred to the Climate Strike Movement before the protest was 16 (2.3%) with 30 mentions in total, while it was more than twice the number with 36 MPs (5.2%) after the strike mentioning the Climate Strike Movement 93 times. 66 MPs (9.6%) directly referred 153 times to the Environmental Policy before the protest, while 84 MPs (12.2%) referred 287 times to it afterwards.

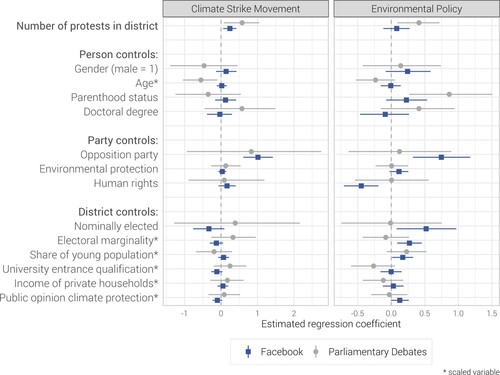

visualizes the effects of local protests on German MPs’ political communication. The plots are based on Model 4 (Full Model) in Appendix D: Main Regression Models. Besides various person-, party- and district-specific control variables, these models also control the pre-protest issue attention on the Climate Strike Movement or Environmental Policy. Positive regression coefficients imply a positive impact of local protests on the number of references to the Climate Strike Movement, with the horizontal lines indicating 95% confidence intervals. More protest events in the electoral district positively affected the MP's attention to the Climate Strike Movement on Facebook and in parliamentary debates. Concerning Environmental Policy, only the attention in parliamentary debates was positively affected, whereas communication on Facebook was not affected.

To a large extent, the analysis corroborates hypothesis H1a, stating that MPs with more environmentalist protest events in their electoral districts refer afterwards more often to the Climate Strike Movement than MPs with fewer protests in their districts. This is slightly different for hypothesis H1b, stating that MPs with more environmentalist protest events in their electoral districts refer more often to Environmental Policy than those with fewer protests in their districts. Concerning Environmental Policy, I can only find evidence for rhetorical responsiveness to local environmentalist protests in parliamentary debates. All in all, the analyses provide evidence for both hypotheses. MPs responded to local protest events by adjusting their attention to the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policy, albeit not consistently in the two examined communication channels.

Moving on to the differences in the communication channels, we can see that the results do not provide evidence for H2, which expected that the effect of local environmentalist street protests on MP communication is stronger on Facebook than in parliamentary debates. On the contrary, rhetorical responsiveness is higher in parliamentary debates than on Facebook. Following these results, the institutional constraints in parliamentary debates hypothesized in the theoretical section are probably less impactful than expected. Moreover, the more interactive communication on Facebook may also encourage MPs without protest events to engage in the public discourse on Environmental Policy.

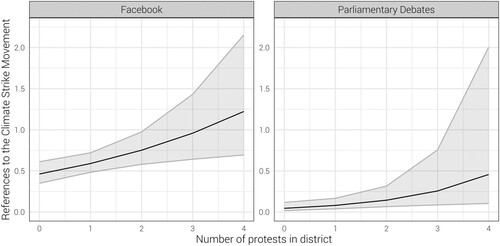

Yet, how do these coefficients translate into the actual communication behaviour of MPs? To illustrate the real-world effects, I plot the predicted number of references relative to the number of protest events in the district. The two panels separately present the predicted values of Climate Strike Movement references for Facebook and parliamentary debates.

The visualizations of the references to the Climate Strike Movement after the first global climate strike day present intriguing results. The values refer to individual MPs. In total, the German Bundestag consists of more than 700 MPs. Furthermore, these values only refer to the time after the first global climate strike (15 March 2019) until the second global climate strike (24 May 2019). MPs with more local protests in their electoral districts refer significantly more often to the Climate Strike Movement after the protests than their peers with fewer protests. This finding is substantial and significant for Facebook but even more so in parliamentary debates.

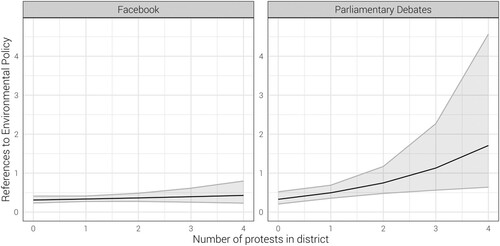

This changes when taking a look at Environmental Policy references. There are no significant effects on Facebook, meaning that regardless of the number of local protests, the number of references related to Environmental Policy stays the same on Facebook. At this point, it is crucial to acknowledge that the Climate Strike Movement aims to change environmental policies. However, the raised attention that the Climate Strike Movement receives after the first global climate strike day in the Facebook communication of German MPs does not translate into more talk about environmental policies on Facebook.

Nevertheless, social media is just one type of political communication, and the MPs’ arguably more crucial political communication does not occur online but in the parliamentary building. The right panel of illustrates how the number of local environmentalist street protests correlates with the number of references to environmental policies in parliamentary debates. Looking at the right panel, we can see how more local environmental protest events in a district during the first global climate strike day led to more references to environmental policies by MPs from those districts. The effect is substantial with MPs, who had four events in their district, talking approximately 3–4 times more often about environmental policies than those without local protest events. This relation, however, is only present in parliamentary debates, while the references to environmental policies on Facebook are not affected by the number of local protest events.

Nevertheless, this finding is a silver lining for protesting social movements. Suppose MPs talk more about social movements on Facebook but not more about the movement’s policy preferences. In that case, it is not necessarily just lip service but can have a meaningful impact on the policy debate in the parliamentary arena. Therefore, the main takeaway of and is that MPs adjust their communicative reactions to local protest events according to the discursive arena. And apparently, political communication in the two discursive arenas follows a different logic. These findings provide new insights into politicians’ behaviour and how they use various discursive arenas for different purposes. MPs signal responsiveness to local protests on Facebook through direct references to the protesting movement. In parliament, this furthermore translates into a generally higher policy emphasis. In sum, this study shows that German MPs had been responsive to the local environmentalist protest events in their districts.

Validity tests

I further conducted various robustness checks to test the validity of my results. The more technical ones (e.g. outlier analyses, additional control variables) are explained in detail in Appendix E. Here, I present two theoretically meaningful tests.

The first test refers to different specifications of the protest variable. Logging the number of protests or excluding MPs without protests in the district does not change the significance of the results. While a binary operationalization of protest events differentiating between no protest and protest in a district leads to a null effect, a threshold of more than one protest event leads to even more significant results. Analysing the number of protest events as factors further supports this finding. In sum, these additional analyses show that not one event’s presence affects the MPs’ attention towards social movements and policy issues but a higher number of protest events. Hence, every additional protest event matters, as more protest events are a stronger public opinion signals.

In the second test, I checked whether short-term and mid-term reactions differ. Therefore, I split the data into the week after the protest (short-term) and the remainder (mid-term). The results remain robust and become even more significant for the mid-term, while the respective models for short-term responses become insignificant. In the short run, the MPs’ responses to the Climate Strike Movement were less driven by protests in their districts, but by other factors. Given that the first global climate strike was on a national (or even global) magnitude with the respective media coverage, the initial effect of the local protest event in the MP’s district was probably overshadowed by the general media coverage. In this context, the effect of the local protests just materialized over time.

Additional analyses

Beyond the primary analyses and validity tests presented above, I also studied further aspects concerning the impact of local protests on political elite communication. The results of these analyses, including a more detailed discussion, can be found in Appendix F: Additional analyses.

First, I added Twitter as a third data source. In contrast to Facebook, Twitter is used more as a platform to discuss current events among elite actors such as other politicians or journalists and less for the communication with geographic constituents (Stier et al. Citation2018b). This difference is also mirrored in the results which show no significant effects of local protests on MP’s communication patterns.

Second, beyond the effect of single protest events on political communication, I studied general patterns of MP’s issue attention to the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policy to see which personal, party or district characteristics drive the issue attention of MPs more generally. In this context, I extended the time frame to the entire 19th legislative period of the German Bundestag until the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Several results are quite striking here. Older MPs refer less frequently to the Climate Strike Movement on Facebook and in parliamentary debates, while MPs with a doctoral degree use more references to Environmental Policy on Facebook and in parliamentary debates. Furthermore, opposition party members refer more often to the movement.

Finally, I examined whether the protests also affected the tone of the MPs’ communication. I expected that MPs of culturally more conservative parties communicate more negatively about these protests while more progressive parties would communicate more positively. This was also true for members of the Left party as they used significantly more positive language regarding the Climate Strike Movement on Facebook after the protests. Yet in sum, most parties did not change their tone after the protests, and other aspects, such as government-opposition dynamics (Proksch et al. Citation2019) were more prevalent.

Discussion and conclusion

Nowadays it is impossible to imagine liberal democracies without social movements, yet they are not the ones making the political decisions. Elected politicians finally decide public policies, and social movements are rather “beggars at the policy gate” (Bernardi, Bischof, and Wouters Citation2021, 304). Therefore, studying when and why politicians pick up public opinion signals sent out by protesting social movements is essential.

With this paper, I illuminate the rhetorical responsiveness of politicians to protesting social movements. Focusing on the Climate Strike Movement in Germany, I answer the question: To what extent have German MPs been responsive to local environmentalist street protests by shifting their attention to the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policy? I analyse Facebook and parliamentary speech data from the 19th German Bundestag, applying dictionary-based quantitative text analyses.

First and foremost, I find evidence that MPs respond to public opinion signals sent by protest events. The results show that MPs with more environmentalist street protests in their districts during the first global climate strike day in March 2019 have been more responsive to the Climate Strike Movement afterwards compared to their colleagues with fewer protests in their respective districts. This finding underlines the relevance even of local protests. Hence, not only major protest events in capital cities have agenda-setting power for the political discourse. Small, local protest events in peripheral regions can also affect the political communication of individual political decision-makers. Therefore, the strategy of the Climate Strike Movement to establish a global climate strike day with a decentralized organization was an excellent choice. Beyond that, the MPs’ rhetorical responsiveness to local protest events shows that even in a party-dominated political system like the German one, there are clear signs of dyadic representation for MPs of both mandate modes.

Second, the results show that politicians adjust their attention and behaviour according to their audience. On Facebook, where politicians meet a lay audience, MPs directly address the Climate Strike Movement more frequently, yet not Environmental Policy issues. This finding is encouraging and discouraging for social movements. While local protest events can lead to more attention to the movement on Facebook, this does not necessarily imply a raised attention for the policy-area this movement wants to change. Nevertheless, politicians with local street protests debate the Climate Strike Movement and Environmental Policies more often in parliamentary speeches. Whether this raised issue attention also translates into actual policy changes remains an open question for subsequent research.

Nevertheless, the study also has some limitations. First, the effect of local protest on the attention to the Climate Strike Movement is robust in most additional validity tests but not in all. However, the arguably more important result that local environmentalist protest affect attention to Environmental Policy in parliamentary debates is robust in all additional validity tests. Second, the protest data only provide information about the presence of an event but neither about its number of participants nor its confrontationality. Future research might address this issue by collecting more comprehensive data. Third, the analysis only covers protests of one, albeit the most important environmental social movement in Germany. Future research could consider additional movements and protests to draw a more comprehensive picture. Beyond that, including various countries in future research projects could help identifying how institutional arrangements affect politicians’ responses to street protests.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (553.7 KB)Acknowledgements

I thank Sven-Oliver Proksch, Ingo Rohlfing, Christine Trampusch, Björn Bremer, Bruno Castanho Silva, Sebastian Stier, the participants of the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics Research Seminar, the anonymous reviewers, and the editor for their constructive comments. Furthermore, I am indebted to Jasmin Spekkers and Marie Melchers for their excellent research assistance.

Data availability

To access replication files for this article, please visit: https://osf.io/b5u6z/?view_only=539b1f7650054ad2baee2d54cd75f1e6

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/14636204.2023.2188350.

Notes

1 In German political discourses and media, the Climate Strike Movement is usually referred to as Fridays for Future. I treat both terms as interchangeable substitutes.

2 Some authors refer to this concept as communicative responsiveness (e.g., Wouters, Staes, and Van Aelst Citation2022).

3 A detailed description of the Climate Strike Movement in Germany can be found in Appendix A1. This description also includes a brief overview of German newspaper coverage on Fridays for Future.

4 The R package quanteda is used to carry out the processing of textual data (Benoit et al. Citation2018).

5 MPs who left the Bundestag during the research period were excluded from the analyses.

6 For a detailed list of all search terms, see Appendix A5.

7 For a detailed list of search terms, see Appendix A5.

References

- Baumann, Markus, Marc Debus, and Tristan Klingelhöfer. 2017. “Keeping One’s Seat: The Competitiveness of MP Renomination in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems.” The Journal of Politics 79: 979–994. doi:10.1086/690945

- Benoit, Kenneth, Watanabe, Kohei, Wang, Haiyan, Nulty, Paul, Obeng, Adam, Müller, Stefan, Matsuo, Akitaka. 2018. “quanteda: An R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data.” Journal of Open Source Software 3: 774. doi:10.21105/joss.00774

- Bernardi, Luca, Daniel Bischof, and Ruud Wouters. 2021. “The Public, the Protester, and the Bill: Do Legislative Agendas Respond to Public Opinion Signals?” Journal of European Public Policy 28: 289–310. doi:10.1080/13501763.2020.1729226

- Borbáth, Endre, and Swen Hutter. 2021. “Protesting Parties in Europe: A Comparative Analysis.” Party Politics 27: 896–908. doi:10.1177/1354068820908023

- Bowler, Shaun. 2017. “Trustees, Delegates, and Responsiveness in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies 50: 766–793. doi:10.1177/0010414015626447

- Castanho Silva, Bruno, and Sven-Oliver Proksch. 2022. “Politicians Unleashed? Political Communication on Twitter and in Parliament in Western Europe.” Political Science Research and Methods 10:776–792. doi:10.1017/psrm.2021.36

- Coffé, Hilde. 2018. “MPs’ Representational Focus in MMP Systems. A Comparison between Germany and New Zealand.” Representation 54: 367–389. doi:10.1080/00344893.2018.1539030

- Downs, Anthony. 1957. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” Journal of Political Economy 65: 135–150. doi:10.1086/257897

- European Union. 2015. EuroVoc Thesaurus. Volume 1, Part B. Luxembourg: Publications Office http://bookshop.europa.eu/uri?target=EUB:NOTICE:OAAJ13002:EN:HTML.

- Fassiotto, Magali, and Sarah A. Soule. 2017. “Loud and Clear: The Effect of Protest Signals on Coongressional Attention.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 22: 17–38. doi:10.17813/1086-671X-22-1-17

- Franzmann, Simon T., Heiko Giebler, and Thomas Poguntke. 2020. “It’s no Longer the Economy, Stupid! Issue Yield at the 2017 German Federal Election.” West European Politics 43: 610–638. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1655963.

- Gamson, William A., and Gadi Wolfsfeld. 1993. “Movements and Media as Interacting Systems.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 528: 114–125. doi:10.1177/0002716293528001009

- Gause, LaGina. 2022. “Revealing Issue Salience via Costly Protest: How Legislative Behavior Following Protest Advantages Low-Resource Groups.” British Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 259–279. doi:10.1017/S0007123420000423.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Robert Klemmensen. 2008. “Government Responsiveness and Political Competition in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies 41: 309–337. doi:10.1177/0010414006297169

- Hutter, Swen, Edgar Grande, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. 2016. Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Jasmine Lorenzini. 2018. “Social Movements in Interaction with Political Parties.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. 2nd ed., edited by David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Holly J. McCammon, 322–337. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Hutter, Swen, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2018. “Who Responds to Protest? Protest Politics and Party Responsiveness in Western Europe.” Party Politics 24: 358–369. doi:10.1177/1354068816657375

- Karlsen, Rune. 2011. “A Platform for Individualized Campaigning? Social Media and Parliamentary Candidates in the 2009 Norwegian Election Campaign.” Policy & Internet 3: 1–25. doi:10.2202/1944-2866.1137

- Kilgo, Danielle K., and Summer Harlow. 2019. “Protests, Media Coverage, and a Hierarchy of Social Struggle.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24: 508–530. doi:10.1177/1940161219853517

- King, Brayden G., Keith G. Bentele, and Sarah A. Soule. 2007. “Protest and Policymaking: Explaining Fluctuation in Congressional Attention to Rights Issues, 1960–1986.” Social Forces 86:137–163. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0101

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Bruno Wüest, Jasmine Lorenzini, Peter Makarov, Matthias Enggist, Klaus Rothenhäusler, Thomas Kurer, et al. 2020. “PolDem-Protest Dataset 30 European Countries, Version 1.”

- Manow, Philip. 2013. “Mixed Rules, Different Roles? An Analysis of the Typical Pathways Into the Bundestag and of MPs’ Parliamentary Behaviour.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 19: 287–308. doi:10.1080/13572334.2013.786962

- Martin, Lanny W., and Georg Vanberg. 2008. “Coalition Government and Political Communication.” Political Research Quarterly 61: 502–516. doi:10.1177/1065912907308348

- McAdam, Doug, and Yang Su. 2002. “The War at Home: Antiwar Protests and Congressional Voting, 1965 to 1973.” American Sociological Review, 696–721. doi:10.2307/3088914

- Miller, Wakken E., and Donald E. Stokes. 1963. “Constituency Influence in Congress.” American Political Science Review 57: 45–56. doi:10.2307/1952717

- Pitkin, Hanna F. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Powell, G. Bingham. 2004. “Political Representation in Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 7:273–296. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.012003.104815

- Proksch, Sven-Oliver, Will Lowe, Jens Wäckerle, and Stuart Soroka. 2019. “Multilingual Sentiment Analysis: A New Approach to Measuring Conflict in Legislative Speeches.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 44:97–131. doi:10.1111/lsq.12218

- Proksch, Sven-Oliver, and Jonathan B. Slapin. 2015. The Politics of Parliamentary Debate: Parties, Rebels and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rauh, Christian. 2015. “Communicating Supranational Governance? The Salience of EU Affairs in the German Bundestag, 1991–2013.” European Union Politics 16: 116–138. doi:10.1177/1465116514551806

- Rauh, Christian, and Jan Schwalbach. 2020. “The ParlSpeech V2 Data Set: Full-Text Corpora of 6.3 Million Parliamentary Speeches in the Key Legislative Chambers of Nine Representative Democracies.”

- Roukounis, Charalampos Nikolaos, and Vassilios A. Tsihrintzis. 2022. “Indices of Coastal Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review.” Environmental Processes 9: 29. doi:10.1007/s40710-022-00577-9.

- Schürmann, Lennart. 2023. “Do Competitive Districts get More Political Attention? Strategic use of Geographic Representation During Campaign and non-Campaign Periods.” Electoral Studies 81: 102575. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102575

- Schürmann, Lennart, and Sebastian Stier. 2023. “Who Represents the Constituency? Online Political Communication by Members of Parliament in the German Mixed-Member Electoral System.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 48: 219–234. doi:10.1111/lsq.12379

- Sommer, Moritz, Sebastian Haunss, Beth Gharrity Gardner, Michael Neuber, and Dieter Rucht. 2020. “Wer demonstriert da? Ergebnisse von Befragungen bei Großprotesten von Fridays for Future in Deutschland im März und November 2019.” In Fridays for Future – Die Jugend gegen den Klimawandel: Konturen der weltweiten Protestbewegung, edited by Sebastian Haunss and Moritz Sommer, 15–66. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

- Steinhardt, H. Christoph. 2017. “Discursive Accommodation: Popular Protest and Strategic Elite Communication in China.” European Political Science Review 9:539–560. doi:10.1017/S1755773916000102

- Stier, Sebastian, Arnim Bleier, Malte Bonart, Fabian Mörsheim, Mahdi Bohlouli, Margarita Nizhegorodov, Lisa Posch, et al. 2018a. “Systematically Monitoring Social Media: The Case of the German Federal Election 2017.” GESIS Papers 2018/04:25.

- Stier, Sebastian, Arnim Bleier, Haiko Lietz, and Markus Strohmaier. 2018b. “Election Campaigning on Social Media: Politicians, Audiences, and the Mediation of Political Communication on Facebook and Twitter.” Political Communication 35: 50–74. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

- Tarrow, Sidney, and Charles Tilly. 2009. “Contentious Politics and Social Movements.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by Carles Boix and Susan C. Stokes, 435–460. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ver Hoef, M. Jay, and Peter L. Boveng. 2007. “Quasi-Poisson vs. Negative Binomial Regression: How Should We Model Overdispersed Count Data?” Ecology 88: 2766–2772. doi:10.1890/07-0043.1

- Walgrave, Stefaan, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2012. “The Complex Agenda-Setting Power of Protest: Demonstrations, Media, Parliament, Government, and Legislation in Belgium, 1993-2000.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 17: 129–156. doi:10.17813/maiq.17.2.pw053m281356572h

- Wallace, Sophia J., Chris Zepeda-Millán, and Michael Jones-Correa. 2014. “Spatial and Temporal Proximity: Examining the Effects of Protests on Political Attitudes.” American Journal of Political Science 58: 433–448. doi:10.1111/ajps.12060

- Wasow, Omar. 2020. “Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion and Voting.” American Political Science Review 114: 638–659. doi:10.1017/S000305542000009X

- Wouters, Ruud. 2019. “The Persuasive Power of Protest. How Protest Wins Public Support.” Social Forces 98: 403–426. doi:10.1093/sf/soy110

- Wouters, Ruud, Julie Sevenans, and Rens Vliegenthart. 2021. “Selective Deafness of Political Parties: Strategic Responsiveness to Media, Protest and Real-World Signals on Immigration in Belgian Parliament.” Parliamentary Affairs 74: 27–51. doi:10.1093/pa/gsz024.

- Wouters, Ruud, Luna Staes, and Peter Van Aelst. 2022. “Word on the Street: Politicians, Mediatized Street Protest, and Responsiveness on Social Media.” Information, Communication & Society 0: 1–30. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2022.2140013

- Wouters, Ruud, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2017. “Demonstrating Power: How Protest Persuades Political Representatives.” American Sociological Review 82: 361–383. doi:10.1177/0003122417690325

- Wüest, Bruno, and Jasmine Lorenzini. 2020. “External Validation of Protest Event Analysis.” In Contention in Times of Crisis: Recession and Political Protest in Thirty European Countries, edited by Bruno Wüest, Hanspeter Kriesi, Jasmine Lorenzini, and Silja Hausermann, 49–76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zittel, Thomas. 2018. “Electoral Systems in Context: Germany.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, edited by Erik S. Herron, Robert J. Pekkanen, and Matthew S. Shugart, 781–801. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zittel, Thomas, Dominic Nyhuis, and Markus Baumann. 2019. “Geographic Representation in Party-Dominated Legislatures: A Quantitative Text Analysis of Parliamentary Questions in the German Bundestag.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 44:681–711. doi:10.1111/lsq.12238