1. Introduction

The therapeutic landscape for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has dramatically changed during the past ten years with the shift from conventional chemo-immunotherapy (CIT) to targeted therapy [Citation1–9]. In earlier comparative studies, the first-in-class Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, ibrutinib, demonstrated superiority over traditional chemotherapy or CIT in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) [Citation1–7]. As opposed to traditional CIT regimens, both ibrutinib and second-generation BTK inhibitors such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib appear to be effective regardless of high-risk mutational status [Citation8,Citation9]. Notably, acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, which are more selective BTK inhibitors, have demonstrated effectiveness comparable to that of ibrutinib but with superior safety profiles [Citation10,Citation11].

BTK inhibitors are administered until progression or toxicity; nevertheless, despite their excellent efficacy, several patients have been found to experience cardiovascular toxicities and BTK mutations associated with resistance [Citation7,Citation12]. Venetoclax, a BCL2 inhibitor, is also recommended until progression, but when combined with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, it can be used as a time-limited treatment [Citation13,Citation14]. Innovative time-limited trials using venetoclax and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody regimens, like the MURANO and CLL14 trials, now disclose long-term outcome results that support widespread use in clinical practice [Citation15,Citation16]. It should be noted that in these studies, achieving undetectable measurable residual disease (uMRD) at the end of therapy has a prognostic impact and is associated with a longer PFS [Citation15,Citation16].

The amazing advancements in CLL treatment options over the past decade have raised major issues regarding variations in the risk-benefit profiles of different treatment regimens and specific patient subgroups. With the complete transformation of the treatment landscape for CLL, it is essential to critically reassess traditional criteria for evaluating efficacy and safety [Citation17]. This is especially important in light of patients’ demand for a more inclusive endpoint: ‘the clinical benefit’.

2. Evaluating CLL treatment efficacy: is progression-free survival enough?

PFS has long been regarded as the gold standard clinical endpoint in CLL for assessing treatment effectiveness [Citation1–6,Citation8–14]. Consequently, both direct and indirect comparison analyses of clinical trials have predominantly relied on PFS as the primary measure of efficacy.

However, patients receiving targeted agents may only partially indicate PFS as prioritized attribute [Citation18]. The concept of PFS, which combines both progression and survival events, can lead to ambiguous results when applied to CLL patients, who tend to be elderly and frequently have underlying health conditions [Citation19]. In such scenarios, the number of deaths occurring without disease progression becomes a relevant consideration, potentially impeding a genuine evaluation of drug efficacy. This was evident in CLL14, a phase 3 clinical trial, where a fixed-duration treatment regimen involving venetoclax and obinutuzumab (VO) was compared to chlorambucil and obinutuzumab (CO) in previously untreated CLL patients with coexisting conditions (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale [CIRS] score higher than 6 or a calculated creatinine clearance of less than 70 ml per minute). In this trial, the 5-year long-term results revealed that among the 80 PFS events recorded in the VO arm, only 52 (65%) were genuinely attributable to disease progression [Citation20].

In an effort to offer a more dependable assessment of true progression events, a recent pooled analysis focused exclusively on progression events when evaluating the efficacy of long-term treatment with ibrutinib [Citation21]. In a cohort of 603 patients treated with ibrutinib, either as a single agent or in combination with an anti-CD20 therapy, across three distinct upfront therapy trials (ECOG1912, RESONATE2, ILLUMINATE), the time to disease progression was calculated while excluding patients who died before experiencing disease progression. This analysis revealed that only 7% of patients who remained on active treatment with ibrutinib actually experienced disease progression [Citation21]. Hence, it is reasonable to expect that in trials involving CLL patients with a higher prevalence of comorbidities, a basic evaluation of disease progression may provide more valuable insights compared to traditional PFS analysis.

One powerful and emerging endpoint in CLL studies is ‘Time to Next Treatment’ (TTNT) [Citation22]. This metric serves as a surrogate marker for the ‘duration of clinical benefit’ and holds significant value in CLL [Citation2–6,Citation8,Citation9,Citation16]. TTNT not only mirrors the treatment’s effectiveness in managing the illness and its symptoms but also serves as a critical clinical endpoint that encompasses the patient’s overall experience. This is achieved by factoring in both patient compliance and tolerance to the experimental treatment [Citation23].

3. Rethinking adverse event assessment in CLL targeted therapy Era

CLL patients receiving targeted agents not only face the challenges of managing their hematologic malignancy but also grapple with ongoing side effects associated with chronic treatment, often involving novel forms of toxicity [Citation17]. In this context, the traditional approach of exclusively concentrating on Grade 3 adverse events (AEs) and reporting only the most severe ones may lead to an underestimation of the overall burden of AEs associated with a specific medication [Citation24]. This approach can inadvertently skew comparisons by disregarding persistent yet lower-grade AEs that ultimately affect a patient’s quality of life (QoL) [Citation24].

In the transition from CIT to targeted therapy, the definitions of AEs according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) remain essential [Citation25]. However, CTCAE does not comprehensively consider the duration and timing of drug exposure in relation to AEs [Citation24]. To enable AE profile comparisons across trials of targeted agents in CLL, it is crucial to have a measure of AE burden that includes both the grade and the number of AEs reported during a trial. A quantitative indicator that takes into account the prevalence and severity of various AEs across time, referred to as the ‘AE burden score,’ has been recently proposed [Citation26].

The AE burden score has been recently validated in a post-hoc analysis of the Alliance trial, comparing ibrutinib, alone or in combination with rituximab, with bendamustine + rituximab (BR) in older patients with previously untreated CLL. The results of this post-hoc analysis suggest that the AE burden score was significantly higher with BR than with ibrutinib during the first six cycles of therapy. Interestingly, among patients who completed six cycles of therapy with ibrutinib, the AE burden score subsequently decreased with continued treatment. It is important to note that the treatments compared differ in terms of drug exposure and agent class [Citation26]. However, the AE burden score provided, for the first time, a standardized framework that combines factors such as the frequency and duration of AEs, not captured by the crude per-patient incidence rate.

Building on the methodology by Ruppert et al. [Citation26], Seymour et al. [Citation27] applied a modified AE burden score that includes grade, duration, and recurrence of AEs to update safety data from the ELEVATE-RR, a randomized phase 3 clinical trial enrolling high-risk relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL patients assigned to receive ibrutinib or acalabrutinib. Notably, Seymour et al.‘s [Citation27] AE burden score methodology, applied to patients who received comparable treatment in terms of agent class and drug exposure, revealed a higher burden of BTKi-related toxicities with ibrutinib as opposed to acalabrutinib. Furthermore, results of the AE burden score for selected events of clinical interest, such as atrial fibrillation/flutter, hypertension, and hemorrhage, further support the superior tolerability of acalabrutinib vs. ibrutinib [Citation27].

Finally, changes in the paradigm of AE assessment necessitate a significant shift in current standards for reporting toxicities, mainly based on patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Clinicians often underestimate the severity of symptoms compared to patients’ self-reports derived from PRO measures, which should be more widely implemented in both clinical trials and clinical practice. Further progress in this area would consider the development of electronic devices to collect and later report PROs [Citation24].

Additionally, the utilization of real-world data, despite its challenges such as unreliable documentation, incomplete follow-ups, and potential biases from patient-reported data or advocacy groups, allows for the identification of clinically significant toxicities in large, unselected CLL patient populations [Citation24].

4. Expert opinion

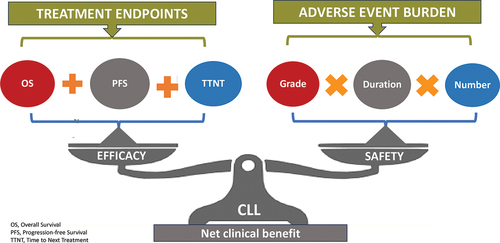

From the perspective of CLL patients, the ideal treatment option would not only focus on improving survival outcomes but also on enhancing Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) [Citation28]. This patient-centric approach recognizes the importance of both dimensions and seeks to maximize what is often referred to as ‘net clinical benefit’ () [Citation29]. This concept operates under the assumption that both doctors and patients will act rationally in accordance with their preferences when making treatment decisions [Citation17].

Figure 1. Visual representation of ‘net clinical benefit’ for CLL patients treated with targeted agents. Efficacy and safety metrics concur to define this inclusive endpoint.

To implement this approach effectively, it requires a prior assessment of the net clinical benefit of novel therapies in CLL. Unfortunately, the evaluation of clinical benefit in cancer therapies, including those for CLL, has historically lacked standardized tools and criteria [Citation30].

However, there is a recent development that holds promise in addressing this issue. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has introduced the Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS) [Citation31]. This scale is primarily based on the analysis of well-conducted phase III trials or meta-analyses and is designed to assist in quantifying the expected net clinical benefit of new cancer treatments [Citation31].

ESMO’s intention to utilize the ESMO-MCBS to evaluate the prospective benefits of new anti-cancer agents approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is a significant step. It signifies the potential for ESMO-MCBS to become a vital instrument for assessing the value of novel therapies. Moreover, it plays a crucial role in making informed decisions about the allocation of limited resources in the provision of affordable cancer care [Citation31].

In the context of CLL, which has seen significant advancements in the development of novel drugs, the ESMO-MCBS would take on particular significance. The ability to measure and communicate the net clinical benefit of these novel treatments in a standardized manner can empower patients to make more informed choices about their therapy options. This transparency and standardized assessment can foster trust between patients and healthcare providers, ultimately leading to better treatment decisions and improved outcomes for CLL patients.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

A peer review on this manuscript is a co-investigator on the HOVON 159 study with acalabrutinib and venetoclax, funded by AbbVie and Astra Zeneca; and co-investigator on the HOVON 158 study with ibrutinib, venetoclax and obinutuzumab, funded by Janssen.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2425–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509388

- Shanafelt TD, Wang XV, Kay, et al. Ibrutinib–rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(5):432–443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817073

- Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2517–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812836

- Moreno C, Greil R, Demirkan F, et al. Ibrutinib plus obinutuzumab in first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (iLLUMINATE): a multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):43–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30788-5

- Munir T, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: up to six years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(12):1353–1363. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25638

- Barr PM, Owen C, Robak T, et al. Up to 8-year follow-up from RESONATE-2: first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022;6(11):3440–3450. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006434

- Molica S, Matutes E, Tam C, et al. Ibrutinib in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 5 years on. Hematol Oncol. 2019;38(2):129–136. doi: 10.1002/hon.2695

- Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, et al. Efficacy and safety in a 4-year follow-up of the ELEVATE-TN study comparing acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2022;36(4):1171–1175. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01485-x

- Tam CS, Brown JR, Kahl BS, et al. Zanubrutinib versus bendamustine and rituximab in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SEQUOIA): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(8):1031–1043. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00293-5

- Byrd JC, Hillmen P, Ghia P, et al. Acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in Previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of the first randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(31):3441–3452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01210

- Brown JR, Eichhorst B, Hillmen P, et al. Zanubrutinib or ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(4):319–332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2211582

- Dickerson T, Wiczer T, Waller A, et al. Hypertension and incident cardiovascular events following ibrutinib initiation. Blood. 2019;134(22):1919–1928. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000840

- Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst B, et al. Venetoclax-rituximab in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 22;378(12):1107–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713976

- Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 6;380(23):2225–2236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815281

- Kater A, Harrup R, Kipps TM, et al. Final 7-year follow-up and retreatment substudy analysis of MURANO: venetoclax-rituximab (venr)-treated patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (R/R CLL). Oral abstract #S201. European Hematology Association 2023 Congress. Jun 9, 2023, Frankfurt DE.

- Al-Sawaf O, Robrecht S, Zhang C, et al. Venetoclax-obinutuzumab for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 6-year results of the randomized CLL14 study. Oral abstract #S145. European Hematology Association 2023 Congress. Jun 9, 2023, Frankfurt DE

- Niemann CU. BTK inhibitors: safety + efficacy = outcome. Blood. 2023, Aug 24;142(8):679–680. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023020974

- Molica S, Laurenti L, Ghia P, et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients’ preferences towards therapies: the Italian experience (CHOICE study). Blood. 2023 23 Nov 2021;138, Suppl 1(Supplement 1):4690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-148308

- Strati P, Parikh SA, Chaffee KG, et al. Relationship between co-morbidities at diagnosis, survival and ultimate cause of death in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): a prospective cohort study. Br J Haematol. 2017 Aug;178(3):394–402. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14785

- Al-Sawaf O, Zhang C, Jin HY, et al. Transcriptomic profiles and 5-year results from the randomized CLL14 study of venetoclax plus obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Commun. 2023 Apr 18;14(1):2147. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37648-w

- Kipps T, Owen C, Flinn IW, et al. Long-term outcomes with continuous ibrutinib in patients with CLL: analysis of time to progression. Poster 627. European Hematology Association 2023 Congress. Jun 9, 2023, Frankfurt DE

- Jacobs R, Lu X, Emond B, et al. Time to next treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia initiating first-line ibrutinib or acalabrutinib. Future Oncol. Online ahead of print. 2023 Jul 21. doi: 10.2217/fon-2023-0436

- Roever L. Endpoints in clinical trials: advantages and limitations. Evid Based Med And Practice. 2016;1(s1):e111. doi: 10.4172/ebmp.1000e111

- Thanarajasingam G, Minasian LM, Baron F, et al. Beyond maximum grade: modernising the assessment and reporting of adverse events in haematological malignancies. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Nov;5(11):e563–e598. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30051-6

- https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_60

- Ruppert AS, Booth AM, Ding W, et al. Adverse event burden in older patients with CLL receiving bendamustine plus rituximab or ibrutinib regimens: alliance A041202. Leukemia. 2021 Oct;35(10):2854–2861. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01342-x

- Seymour JF, Byrd JC, Ghia P, et al. Detailed safety profile of acalabrutinib vs ibrutinib in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the ELEVATE-RR trial. Blood. 2023 Aug 24;142(8):687–699. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022018818

- Seymour JF, Gaitonde P, Emeribe U, et al. A Quality-AdjustedmSurvival (Q-TWiST) analysis to assess benefit-risk of acalabrutinib versus idelalisib/bendamustine plus rituximab or ibrutinib among relapsed/refractory (R/R) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients [abstract]. Blood. 2021;138(suppl 1):3722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-147112

- Molica S, Allsup D, Polliack A, et al. The net clinical benefit of targeted agents in the upfront treatment of elderly/unfit chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients: results of network meta-analysis. Eur J Haematol. 2023 Jun;110(6):774–777. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13943

- Cufer T, Ciuleanu TE, Berzinec P, et al. Access to novel drugs for non-small cell lung cancer in central and Southeastern Europe: a central European cooperative Oncology group analysis. Oncology. 2020 Mar;25(3):e598–e601. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0523

- Kiesewetter B, Dafni U, de Vries EGE, et al. ESMO-Magnitude of clinical benefit Scale for haematological malignancies (ESMO-MCBS: H) version 1.0. Ann Oncol. 2023 Sep;34(9):734–771. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.06.002