ABSTRACT

Expanding debate surrounds the impacts the rapidly increasing volume of cruise ships to the Arctic region are having on local ports and communities. This debate largely centres on the influx of visitors and concern about cultural interaction. This paper evaluates the feasibility of using the concept of Social License to Operate (SLO) in Arctic cruise tourism by identifying how attitudes and perceptions pertain to acceptance and trust. Insights are gathered from both passengers and local stakeholders in Iceland and Faroe Islands. Results reveal cruise companies’ dominance in itinerary planning, with minimal communication among destinations. Economic concerns overshadow collaborative planning, leading to varying levels of acceptance among the diverse stakeholders of cruise tourism. While those benefiting economically support the industry, others express reservations. This dichotomy in opinion regarding acceptance and trust highlights the SLO’s challenges within tourism in general. For SLO to have relevance and legitimacy within cruise tourism, flow and circulation of perspectives is critical.

1. Introduction

The Arctic, with its diverse landscapes and cultures, has witnessed a surge in tourism over the past few decades. Cruise tourism, in particular, has played a pivotal role in this transformation. The early ventures were characterized by a limited number of vessels, primarily catering to adventurous travellers seeking to experience the allure of the Arctic’s landscapes and cultures (Orams, Citation2010). However, since the last millennium, Arctic cruise tourism has witnessed a significant escalation (Bystrowska & Dawson, Citation2017; Hansen-Magnusson & Gehrke, Citation2023; Johnston et al., Citation2017). The region’s remoteness and unique nature, filtering into what has been described as the ‘Arctification’ (Lundén et al., Citation2023), attract an ever-increasing number of cruise operators seeking to provide unique experiences for more and more tourists. Consequently, a growing debate is surrounding Arctic ports and destinations as the cruise business expands. This debate primarily revolves around the surge in visitor numbers congregating in remote and thinly populated communities (Stonehouse & Snyder, Citation2010). Issues are also emerging regarding the conduct of cruise tourists as they witness unfamiliar local customs, like traditional hunting or animal culling (Haworth, Citation2023), or overwhelm local residents through inquisitive observations of their daily lives.

Despite some notions of trust within the context of social capital (Heikkinen et al., Citation2021) and social acceptance in terms of community needs (Ren et al., Citation2021) these concepts have not been fully developed or adequately explored in the discussion of Arctic cruise tourism. Similar debates linked to social acceptance have, however, evolved in other industries, particularly from the extractive industries, such as mining and forestry, and resulted in a principle known as Social License to Operate (SLO) (Lesser et al., Citation2021). SLO revolves around acceptance, communication, public participation, and, notably, the local benefits derived from the industry (Moffat et al., Citation2016; Prno & Slocombe, Citation2012). Robertsen et al. (Citation2024) stress that gaining trust and acceptance from local residents become particularly pivotal for industries using local natural resources and impacting expansive land and seascapes, subsequently often causing notable environmental and social impacts at a local level. They also note that regardless of these impacts, such industries generally generate substantial benefits far beyond the affected local communities. This disparity in the distribution of risks, costs, and benefits is likely to serve as a catalyst for conflicts within local communities. It has, for example, been shown (Jijelava & Vanclay, Citation2018; Moffat et al., Citation2016) that as the expectations and demands of these communities towards the industries rise, failure to secure social acceptance can lead to conflicts and delays and thus results in significant costs for the industries, including project interruptions and in some cases termination.

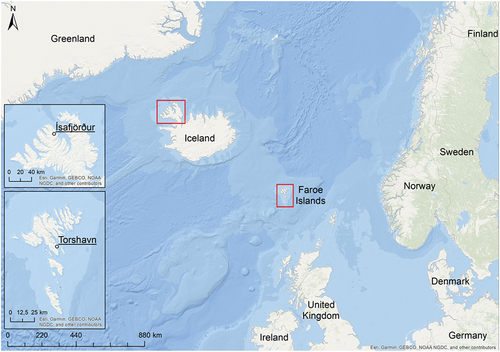

An evolved expression of the SLO concept is rarely applied to the tourism sector. This seems, however, to be changing alongside the rapidly expanding tourism and consequently increased tourism impact. Notably, one of the most rapidly growing sectors within tourism is cruise tourism, which typically lacks local ownership. Moreover, because of its significant environmental footprint and local impact (Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010; Howitt et al., Citation2010; Simonsen et al., Citation2019), cruise tourism is in many ways comparable to extractive industries. Not only is the number of ships increasing but there is also a trend toward larger vessels. Consequently, one issue arising is the concern over excessive numbers of tourists concentrated in popular destination ports and areas. In this situation, the problem is not directly about achieving acceptance of cruise tourism per se, but rather managing the flow of visitors. As a response to that challenge, this paper aims to explore how acceptance and increased trust in cruise tourism could be enhanced by examining the diverse interactions between destinations and visiting cruise business. Perspectives are drawn from both tourists aboard a cruise ship arriving at an Arctic port to understand how they perceive the destination, as well as the viewpoint of port and destination communities observing the docking ship to understand how they perceive that arrival. The study focuses on two study sites representing popular ports in the Sub-Arctic, namely the Westfjords of Iceland and Tórshavn in the Faroe Islands. These ports exemplify the rural Arctic as well as the rapid expansion of cruise tourism in the region.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social acceptance and social license to operate

SLO emerged around the turn of the last century (Thomson & Boutilier, Citation2011). Before that, several concepts focusing on examining the interactions between local stakeholders and economic entities had come to the fore. The most widely recognized one is probably Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) that focuses on the company’s perspective, contributing to social and environmental sustainability (Jenkins & Yakovleva, Citation2006; Tuulentie et al., Citation2019). According to Henryson (Citation2021) its debate is rooted in the pressure on companies to have more inclusive criteria in mind than just profit or loss for shareholders. Companies’ social responsibility includes, for example, taking on increased costs for waste disposal or spending more time finding a more diverse group of staff and managers. Thus, from a business point of view, it may be seen as both time-consuming and costly, but also as evidence of responsible operation. As the emphasis on CSR has intensified in recent decades, numerous significant questions have arisen, such as its lack of social acceptance from the local community.

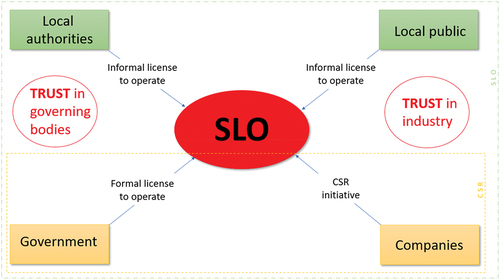

While CSR takes a company-centric perspective, SLO incorporates the community’s perspective. Yet, there is no universal agreement on a single definition of SLO. Moffat et al. (Citation2016) notes that it is often described as embodying the unwritten social contract between the corporations and communities. According to Thomson and Boutilier (Citation2011) SLO is rooted in the beliefs, perceptions and opinions of the local community and other stakeholders regarding the operational business. Consequently, it is accepted by the community and remains intangible unless attempts are made to measure these beliefs, perceptions, and opinions. SLO is thus not an administrative license granted by the authorities, but an interactive process to create and maintain acceptance and trust (). Thomson and Boutilier (Citation2020) have divided this process into three stages, the first one being ‘legitimacy’ that is reached when a company obtains a formal license to operate from the governmental authorities and thus a legal acceptance. The second stage ‘credibility’ is essential to obtain social approval. Once approved the business progresses to the final stage ‘trust’. There are, however, many levels of trust, the highest one being when the community identifies itself with the business. As trust is flexible it can also get lost as well as gained. This is reinforced by Thomson and Boutilier (Citation2020) stressing that due to its dynamic nature SLO must be earned and then maintained since the community’s beliefs, perceptions and opinions are subject to change as new information is acquired. Thus, the importance of understanding the local’s perception towards the operational benefits and impacts is critical. While main criticism towards CSR has been that it is only lip service (Dashwood, Citation2012), SLO has been criticized for its obscurity and the difficulty of recognizing when a community has not ‘granted’ SLO (Owen & Kemp, Citation2013; Tuulentie et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1. The relationship between CSR and SLO. Industries need formal governmental approval to operate. Companies need to take their own initiative to embrace CSR. SLO, additionally, requires an informal license to operate from the local authorities and residents, which is a prerequisite for trust-building.

2.2. SLO in tourism

Concepts underpinning SLO, such as fostering trust and securing social commitment, have resonated within the tourism research literature since the 1980s. For example, research in community-based tourism (CBT) which emphasizes the importance of community ownership, allowing local communities to actively manage and benefit from tourism resources (Zielinski et al., Citation2021). CBT attempts to create commercial and social values for local destinations (Dangi & Jamal, Citation2016), while building trust between tourists and local communities, thereby fostering positive interactions (Priatmoko et al., Citation2021). However, the SLO concept within the context of tourism in English language scientific literature remains limited. Only eight scientific papers addressing SLO in tourism have been published (), covering a relatively broad spectrum of subsectors of tourism, including areas like home sharing platforms, equestrian sports, mountain destinations, ecotourism, event tourism, and nature-based tourism. This diversity underscores the broad applicability of the SLO concept across various domains of the tourism industry.

Table 1. Overview of existing scientific literature concerning SLO in tourism.

Most of these literatures take a company-centric approach, focusing on factors that facilitate the tourism sector in attaining a SLO. Williams et al. (Citation2007) emphasize the importance of CSR strategies in establishing enduring community based SLO, which grants businesses enhanced access to crucial resources for improving their competitive advantages. They argue that success of these strategies is contingent on the capacity of stakeholder groups to advocate for community concerns and be recognized as credible and trustworthy actors. The crucial role of CSR in securing a SLO for successful operation of ecotourism is also emphasized in the study of Bickford et al. (Citation2017). They emphasize the significance of cooperation, ethical practices, and alignment with local community values as essential components. Ponsford and Williams (Citation2010) demonstrate the importance for achieving SLO in event tourism. Their research reveals how organizations can avoid resistance and construction delays by attentively engaging stakeholders in the planning process through public presentations, forums, meetings, and other forms of expression. This approach helps prevent reputation damage from activism and minimized costly delays. Douglas et al. (Citation2022) examine the role of trust as a fundamental factor shaping SLO by exploring its significance in equestrian sports and highlighting the implicit understanding between the public and animal-involved industries. Their findings advocate for transparency, effective communication of shared values and a proactive stance to foster and maintain trust.

The remaining literature addresses the challenges of maintaining SLO. In a study on corporate-civil society relationships in mountain destinations, Williams et al. (Citation2012) note that changes in ownership can impact the social license, highlighting the need for sustained, well-structured engagement beyond personal connections. Suopajärvi et al. (Citation2020) focuses on challenges in employing SLO in tourism compared to other extractive industries. They argue that local acceptance is often presumed by the tourism industry as Arctic tourism has hitherto been rooted in local entrepreneurship. However, they emphasize that a growing share of international investors in local Arctic tourism is perceived as a potential threat to the advancement of tourism social sustainability. The temporary nature of seasonal employment in tourism is furthermore seen as yielding only short-term economic advantages instead of long-term prosperity, emphasizing the idea that the tourism industry’s acceptance decreases as it increasingly depends on non-regional ownership or an external workforce. Baumber et al. (Citation2019) contribute to this challenge by examining the applicability of the SLO concept in the sharing economy and developing a framework for analysing SLO within the sharing economy, highlighting fundamental components such as trust, distributional fairness, procedural fairness, and confidence in governance. The subsequent work by Baumber et al. (Citation2021) narrows the focus to home sharing platforms like Airbnb, emphasizing SLO potential to address the undesirable concerns associated with such platforms. Their study identifies challenges to the social license of home sharing, including impacts on local residents and accommodation providers, lack of transparency, limited community engagement, and perceived regulatory inequalities. Tourism is notably discussed not only as an entity striving for ongoing approval of its operations but also as a vehicle for gaining social acceptance of activities unrelated to tourism itself. McGaurr and Lester (Citation2017), explore, for example, how environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) perceive tourism as a tool for obtaining social endorsement for the preservation of natural areas, as well as the conflicts ENGOs encounter when tourism itself becomes a contentious issue.

Given the limited number of scientific papers published on the topic so far, it’s challenging to identify specific research trends. Nonetheless, the evolving literature stresses the importance of local acceptance, transparency, and proactive engagement for sustaining SLO in different tourism contexts. They furthermore emphasize the significance of relationship management within the tourism sector for ensuring trust and acceptance among destination stakeholders. As the sector increasingly depends on non-regional ownership or external workforces, maintaining acceptance and trust will grow more challenging. This trend is particularly evident in the case of the cruise ship tourism industry operating in the Arctic.

3. Study areas

The study encompasses the Westfjords in Iceland and Tórshavn in Faroe Islands, situated in the North Atlantic Ocean (). Both locations are increasingly favoured as destinations of cruise ship companies.

3.1. Westfjords – Iceland

The Westfjords region is characterized by steep mountains and narrow fjords with limited agricultural land but abundant fishing grounds. Historically, settlement patterns were characterized by individual farms scattered across the region lowlands. Urbanization began in early 20th century, when people moved to the coastal areas giving rise to numerous small fishing communities. Since 1950, the region has experienced out-migration, attributed to various factors such as changes in the fishing industry (Matthíasson, Citation2003). Recent growth in aquaculture and tourism has led to population resurgence. At the start of 2024, a total of 7.168 inhabitants lived in the Westfjords, of whom 2.679 resided in the region´s largest town, Ísafjörður (Statistics Iceland, Citation2024).

In recent years there has been a notable increase in the number and size of cruise ships visiting ports in the Westfjords, particularly in Ísafjörður that ranks as the third busiest cruise port in Iceland, after the ports in Reykjavík and Akureyri. From only three cruise ships arriving in 1996, there has been an increase in days where over three ships call port the same day, bringing over 6000 passengers to town. In 2023, there were seven days like this (Ísafjörður town, Citation2024). Recent research (i.Riendeau, Citation2023) show that behaviour of passengers visiting the old town has fuelled increased intolerance for large crowds generated from the ships and growing concerns about how this overload of visitors will impact socially and environmentally. Consequently, local debate has been growing on how to limit the increasing number of cruise calls by larger ships to Ísafjörður (James et al., Citation2020). The global pandemic significantly reduced cruise calls to Ísafjörður in 2020 and 2021, but the industry has swiftly rebounded. By 2022, passenger numbers had nearly returned to pre-pandemic levels, with 86,286 passengers, which increased to 246.882 passengers in 2023 (Ísafjörður town, Citation2024).

3.2. Tórshavn – Faroe Islands

Tórshavn, the capital of the Faroe Islands hosts over 40% of the population, approximately 22.000 out of 54.500 residents (Statistics Faroe Islands, Citation2024). Most cruise ships visiting the Faroes dock at its port that is located by the old city centre. Issues like passengers disturbing residents’ homes, peaking through windows, overcrowding in shops and cafes are common. Despite controversy, the port actively seeks more cruise ships as part of their business and expansion strategy. Other ports, such as Klaksvík, Runavík, and Suðuroy, also welcome cruise ships for potential income. However, there is no coordinated national strategy regarding cruise tourism in the Faroes. Since 2003, cruise arrivals have fluctuated between 34 and 71, with passenger numbers varying from approximately 20.000 to 90.000 (Visit Faroe Islands, Citation2023). The COVID-19 pandemic halted activities in 2020 and 2021, but in 2022, the number of arrivals was 43, with nearly 30,000 passengers. Statistics for 2023 are not yet available but estimated to be around 50 ships (Visit Faroe Islands, Citation2023).

The traditional practice of pilot whale hunting, grindadráp, has been a source of major controversy in the Faroes for many decades. Most Faroese citizens, as well as the national authorities, insist on its legitimacy and sustainability (Bogadóttir & Olsen, Citation2017), and tourists who actively choose the Faroes as their destination are aware of this practice in advance of their arrival. However, a recent incident of a whale killing coinciding with a cruise ship berthing in Tórshavn suggests a disconnect and lack of mutual understanding between the cruise industry and the local community. According to Haworth (Citation2023) a reporter by the ABC News, the cruise line Ambassador following the incident issued an apology to their passengers:

We were incredibly disappointed that this hunt occurred at the time that our ship was in port. We strongly object to this outdated practice, and have been working with our partner, ORCA, a charity dedicated to studying and protecting whales, dolphins and porpoises in UK and European waters, to encourage change since 2021.

Moreover, the cruise line company stated that they fully appreciate that ‘witnessing this local event would have been distressing for most of the passengers onboard. Accordingly, we would like to sincerely apologize to them for any undue upset’ (Haworth, Citation2023). The locals, on the other hand, thought that the cruise liners owed the Faroese an apologise (Clark, Citation2023), emphasizing the lack of mutual understanding.

4. Methodological approach

A qualitative methodological approach was employed to assess the applicability of SLO within Arctic cruise tourism and to explore the attitudes and perceptions of cruise tourism stakeholders regarding acceptance and trust. The methodological approach was designed to study Arctic cruise tourism as a multifaceted phenomenon through identifying the attitudes of several stakeholder groups (i.e. cruise passengers, local port and public administrators, tourism operators, shop keepers, and general public) in relation to one particular cruise tour. Data collection involved participatory observation, focus group discussion and semi-structured interviews. This included cruise passengers on a medium-sized cruise ship carrying 900 passengers, visiting Faroe Island and Iceland between 6th − 12th of September 2023, while crossing the North Atlantic from Denmark towards Greenland and U.S.A.. To analyse the attitudes of cruise passengers, two roundtable discussions were conducted on board the cruise ship each, including between 60 and 70 passengers. Additionally, participatory observation and ethnographic research on ship and around port destinations were undertaken to obtain more enriched experiences and deeper insights. Field-based participatory observation allows researchers to immerse themselves in the daily life and activities of the guests on board, providing a deeper understanding of the guests’ perspectives, behaviours, and social dynamics (Roque et al., Citation2024). Furthermore, using an autoethnography approach enables researchers to use their personal experience to understand collaborative processes, effectively serving as a form of structured reflection (Murphy et al., Citation2021).

To tap into the perceptions and attitudes of local stakeholders towards the cruise visits, three focus group meetings were arranged and conducted in connection with the cruise ship’s visits to the ports in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands on the 6th and 14th of September and in Ísafjörður, Iceland on the 12th of September. Focus group discussions are widely used in perception studies and are closely linked to the rise of participatory research. This method aims to draw from the complex individual experiences, beliefs, perceptions, and attitudes of the participants through a guided and moderated interaction (Cornwall & Jewkes, Citation1995; Hayward et al., Citation2004; Morgan, Citation1996). A total of seven participants contributed to the meeting in Ísafjörður, representing two from the public administration sector, i.e. mayor and harbour master, three representatives from the local tourism industry, one specialist from the Westfjords regional development office and another from the Westfjords museum. Five participants reside in or around Ísafjörður, while two were from the southern part of the Westfjords. In Tórshavn, a total of ten participants attended to the two meetings, representing the local and the national tourism industry, harbour administration, local neighbourhood groups, whalers, and local shopkeepers. The focus group discussions at both sites followed a semi-structured interview framework, ensuring comprehensive coverage of desired aspects, including the participants´ perceptions of the impacts and managements of cruise tourism, as well as their perception on SLO and trust in the cruise industry. The focus group meetings, roundtable discussions, and individual passenger interviews were all recorded and transcribed. During data analysis, the focus was on identifying themes to scrutinize the discourse and then linked it to the theoretical framework underlying this research.

5. Results

5.1. Attitude of cruise passengers

The cruise passengers that visited the Faroe Islands and Iceland highlighted the value of local tour guides who can provide insights into the local way of life, and found this aspect of their visit most enjoyable, or like one expressed it: ‘… my highlight experience is the local people’. Passengers thus feel that the focus should be more on the people rather than sites as such and mentioned their desire for more meaningful interactions with local communities and how some tours lacked such interactions:

My concern was that although we saw the sites, we really didn’t see the people and get to interact with them. We’ve gone on lots of trips where we had more interaction with the locals, which we thoroughly enjoy.

… the guide has been talking for something like I would say one and a half hour during trip all in all, and nothing was told about that. I mean, you should tell about the people, what they do for a living there, not only at what age the children go to school and leave school, etc. That’s the same all over the world nowadays.

I felt like the high point for me was that our tour guides were locals and told us about life. … So that’s what I found most amazing was the guides, the guides who really shared what life is like here and they were very happy to share it.

Observation and discussion with onboard passengers underscored that they enjoy having that local knowledge to hand. It helps them navigate usually unfamiliar landscapes and locations, or as one said: ‘It is good to have an awareness of local culture, lifestyle, and practices’. However, our observation reveals that there is a gap in bringing local knowledge, including a cultural briefing, to the cruise tourists that would help them arrive in a location armed with at least some of that local knowledge.

The passengers furthermore showed a concern about what the locals think about them, as well as the potential negative impact of tourism on small communities, both culturally and environmentally: ‘having all these visitors or is it just a nuisance, so here comes another ship’. Subsequently, questions were raised about whether tourists should spend more time, money, and effort interacting with and contributing to these communities.

And when we go to these local communities, I always think about the children and the elderly and ways that we can contribute to the communities there. I’m not sure how that could be done, but I think that’s something important that we should consider when we travel to these locations.

I don’t know what people are looking for in these small communities, when they get tourists parading through and then leaving. Do they feel like we should be spending more time, spending more money, more interaction with them? I just wonder if, you know, we just came to look like they were in a zoo.

The discussion with the passengers furthermore touched on the delicate balance between promoting tourism and preserving the natural and cultural heritage of a site, indicating their social and environmental concern. One lady expressed: ‘I facetiously said to a friend when I was coming here that, I best get here now to see it before it is really destroyed, but in my doing so I will help destroy it’. This aligns with the rapid rise in so-called ‘last chance tourism’ in recent years, a trend where tourists desire to experience cultural and natural uniqueness before their disappearance (e.g. Salim et al., Citation2023).

As regards passengers’ concern with marketing and planning cruise tourism in the Arctic, many expressed the importance of local communities having a say in how tourism is managed and how it interacts with tourists. It was suggested that the cruise industry should engage with local communities on their terms. Hence, the discussion with the passengers highlighted how according to their experiences, tourism destinations can change over time and with proper management cruise visitors could even play a role in preserving the charm and culture of these places.

I’m enjoying the uniqueness of this area. It’s isolation, obviously, parts of it that are unspoilt, but I’m also seeing the consequences. … The extreme of tourists is what’s being seen in places like Dubrovnik, in Amsterdam, Venice, banning ships, so reducing the number of tourists - yes.

… what’s needed is forward planning, strategic outlooks. … Am I being selfish because I’m coming from a part of the world that’s polluted and taking advantage and now, I’m expecting another country not to enjoy the capitalistic rewards if they are so, by not wanting them to spoil what I’m going to come and see.

And they emphasized the importance of the local’s participation in tourism planning and management in order not to exceed the tolerance of the local people and at the same time to preserve the original attractions:

… I think it is wonderful that before Iceland is destroyed and Greenland, that you’re taking seriously the ideas that the people involved should have a say in what’s going on. But what always seems to happen anyway is the high economic, the control of large corporations just tends to trample over everything, and it just doesn’t turn out the way we hope it would.

Your countrymen need to have a stake in how it is we interact with you. If you don’t want your communities’ overrun by, you know, very large cruise ships, then that’s up to you to decide because we’re interested in being here and we’ll be here on your terms, make terms that you like.

One respondent emphasized the necessity of placing planning and management responsibilities in the hands of locals, highlighting the crucial role of the community in promoting responsible tourism. This demonstrates the importance of local planning and management, enabling the local communities to harness tourism for increasing their well-being, rather than letting tourism exploit their destinations solely for its own gain.

5.2. Attitude of local stakeholders

5.2.1. Westfjords - Iceland

All the stakeholder representatives participating in the Westfjords focus group expressed a consensus regarding the predominantly positive impact of cruise ships tourism on the local communities. They attribute this positivity primarily to the ‘significant economic benefits these vessels bring’ and the diverse employment opportunities they provide within the region. They underscore that they do not consider the cruise ships as competing with the local tourism industry. They don’t perceive the current quantity of larger cruise ships as problematic, attributing it to the brief duration of their presence, typically limited to a few weeks in the summer. However, representatives from the southern part of the Westfjords, where ongoing efforts aim to attract more cruise ships, mentioned their goal of only allowing smaller cruises, aligning with their local community’s wishes. Regarding potential concerns or negative impacts associated with cruise ships in the Westfjords, participants generally view adverse impacts on the environment, social dynamics, and culture as relatively minor. They expressed a sense that the community welcomes these tourists. Nonetheless, the two specialist representatives expressed concerns about environmental pollution during ship docking. These concerns shifted the discussion towards the management and governance of cruise tourism in the region, focusing on areas of improvement. One participant mentioned a lack of control in the cruise business in general, emphasizing the need for more careful steering and management. Another, reflecting on the changing sentiments over time noted a shift from initial excitement to concerns about reaching the limits of the locals’ tolerance, suggesting that impacts may already extend beyond economic dimensions:

Well, I would say… because I started working on this just after 2000, and have followed the development, from everyone being just insanely excited, so eager to this, very happy with just the honour shown to us by the coming of the ships - you know -, to - you know - the absolute inverse … , so I would say that we should have needed to be more careful along the way - you know - with steering … … I would say this summer it just ran over - you know - it’s just that the limits of tolerance were just really reached.

This stimulated a subsequent discussion about the importance of tourism management, the necessity for improved infrastructure and the provision of recreational facilities for cruise ship visitors. The participants were furthermore unanimous that the information provided to passengers about the local community was not good, citing inaccuracies and a lack of dialogue. They stressed the importance of accurate information to enhance tourists’ respect for the visited community and emphasized the need for improved communication: ‘What is missing is this conversation between the two, you know, just the flow of information’; ‘Yes, there is a lack of this conversation’.

None of the participants were familiar with the concept of SLO. Upon introduction, they found SLO to be a practical tool that points to the importance of dialogue, communication, and tourist satisfaction to maintain a positive impact. Especially when thinking about future planning and management of cruise tourism, they recognized SLO to be important in developing this type of tourism in harmony with the local communities:

Because this is definitely needed, you know, we all heard about the protest in Norway, I guess some of you at least were a bit … you know, how locals have been treating the cruise visitors, … And I would say, before heading into that direction, we need to start to think about this seriously.

This was further discussed, and all participants agreed that future considerations should prioritize tourism management, encompassing logistics and societal impact, with an emphasis on fostering partnerships between cruise companies, communities, and destinations.

5.2.2. Tórshavn – Faroe Islands

In the Faroese case, the focus group participants were generally less positive about cruise tourism. However, those stakeholder groups who benefit economically from cruise ships, such as the local harbour, the tour, transport, and shipping companies, view cruise tourism as a source of income that has the potential to grow, and therefore legitimate. Although these attitudes reflect an acceptance of cruise tourism, these representatives are also aware of the lacking acceptance and trust in cruise tourism in the society more generally. When asked what the cruise industry could do to improve, they mentioned environmental factors such as switching from polluting fuel to electric power plus the need for better coordination between the harbours and the tourism operators, shopkeepers seeking to benefit from those flows. Despite showing acceptance of the cruise industry, they did not express high level of trust. For example, on the issue of collecting a higher price per passenger coming to port, they described the cruise operators as notoriously hard negotiators, and expressed concern that the cruise companies would simply find alternative ports.

From a strategic national tourism planning perspective, cruise tourism in its current form is not economically, environmentally, or socially viable, because the economic and social revenues do not outweigh the negative impacts. In comparison to other forms of tourism, revenues from cruise tourism are negligible. Negative impacts mentioned were over-crowding, pollution on local and global level, and tourists that are not necessarily interested in local cultures and traditions: ‘The ship is the destination for this kind of tourism, not the visited ports. The Faroes are just an unimportant stop along their way to the Arctic’. When it comes to the local community in and around Tórshavn, the situation is difficult because the cruise industry benefits some locals (such as through increased economic activity/profit and employment) and is detrimental to other locals (through crowding, air and noise pollution). Moreover, the global environmental dimension of cruise-tourism can hardly be ignored anymore even in the Faroes ‘considering the state of the climate’. The lack of communication with the cruise operators and the resulting unpredictability makes coordination and planning very difficult for the local tourism office. For many local shopkeepers, the cruise industry also seems uncoordinated, and cruise passengers tend to use local shops as tourist information offices, rather than buying anything. The cruise tourists are generally not interested in buying other things than small souvenirs or items that are branded as local such as woollen sweaters: ‘Everything else is cheaper where they come from anyway’. The shopkeeper expressed a wish to adapt and called for strategic planning to make it possible to tap into the cruise market: ‘These 900 people that come [off the ship] how can I reach them?’ To which the representative of local homeowners objected: ‘The souvenir city-centre of Reykjavik is no dream scenario to my mind … ’

The stakeholder representing the whaler’s association stressed that they have nothing against cruise tourism. Being a voluntary group of citizens they simply want to preserve the right and tradition to kill whales because they consider it a sustainable way to get food. The representative emphasized that everything is done in the open, everyone can watch, and everyone can get a share of the food. There is, however, an increasing pressure on these traditional practices when they affect industries, as expressed by another particpant: ‘But then the ships just go to some other port in Norway or Iceland where they hunt the large whales, so you know, there are standards and then there are double standards’.

6. Discussion

6.1. Cruise tourism moving from sustainability to regeneration?

Over the past decade, cruise ship tourism has been taking more and more space in the field of the rapidly growing tourism sector in the Arctic. Unlike existing tourism in the region, which predominantly involves small and medium-sized locally owned enterprises, cruise ships are non-regionally owned. The cruise companies are driven by a business model centred around onboard occupancy and delivery of ‘popular’ tour packages and experience onshore at the port destinations. While some local input exists, decisions are overwhelmingly influenced by what the local tour operations think will please cruise tourists and encourage cruise companies to return to their ports. This grants the cruise companies a certain freedom in their operations, which according to recent research (i.e. Bogason et al., Citation2021; Hoarau-Hemstra et al., Citation2023) dictate the routes and developments in the Arctic with minimal communication between ports. The findings of this research support this, indicating that both the tourism industry and local authorities are apprehensive about losing business to competing Arctic ports. Consequently, they avoid imposing any restrictions. Each port or destination therefore continue to operate independently, without sharing views and experiences with others. In contrast, the cruise companies are centralized under a few significant players, employing a uniform business strategy across all ports. The business perspective is unified, while the destination perspective is fragmented and competing against each other. Consequently, there is a lack of a coherent plan among destinations, with economic considerations being the sole driving factor.

This is noteworthy considering that both Ísafjörður and Tórshavn ports are members of Cruise Europe (https://www.cruiseeurope.com/), an organization dedicated to facilitating dialogue among ports to promote sustainable cruise tourism. These findings support scholars demonstrating that despite growing emphasis in the past three decades, minimal progress has been made in fostering a more sustainable tourism sector (e.g. Hall, Citation2019; Sharpley, Citation2020). Accordingly, the sustainable tourism development agenda has been criticized for being co-opter to continual economic growth, driving environmental devastation and social inequalities (Bellato et al., Citation2022). In advocating for the environmental and social aspects of sustainability, Goodwin (Citation2012) introduced the notion of responsible tourism emphasizing tourism’s role in fostering a more equitable society. However, there is an increasing debate about the potential for tourists to benefit the destination rather than simply behaving responsibly. This has resulted in a shift towards so-called regenerative tourism that seeks to ensure that travel and tourism deliver a net positive benefit to people, places and nature, and that it supports the long-term renewal and flourishing of social and ecological systems (Dredge, Citation2022). This study demonstrates that this movement also applies to cruise tourism. It is crucial for cruise ships to embrace this ideology in all their planning and operation, as they represent large foreign companies that exploit vulnerable natural and cultural resources. In this context, SLO can serve as a valuable tool for the cruise industry. This is supported by cruise passengers, who despite choosing a mode of travel that classifies as mass tourism, anticipate unique experiences at each port destination. It is noteworthy that they prioritize interactions with local communities over nature, and they want to contribute to the local communities. Their desire to immerse themselves in the local life and culture of each port of call, highlights, however, a dilemma the cruise passengers have in relation to the local communities.

6.2. Social acceptance and trust in Arctic cruise tourism

Impacts of cruise tourism are very diverse, encompassing positive as well as negative aspects. The role of the different stakeholders in managing these impacts is complex and challenging. As expected, the emphasis on the economic, societal, cultural, and environmental dimensions of sustainability varies among stakeholders, depending on their perspectives and position within the cruise industry. In both case studies, it is evident that stakeholders who benefit directly from the cruise industry emphasize economical dimension and express a high level of acceptance. Conversely, non-benefitting residents express a corresponding lack of acceptance. This divergence in opinion regarding acceptance and trust in cruise tourism demonstrates the inherent challenges faced by concepts like SLO. For industry to maintain a social license, Dumbrell et al. (Citation2021) have identified five critical conditions: (1) delivery (or perception) of net economic benefits beyond the company; (2) adequate stakeholder consultation; (3) minimal media coverage; (4) minimal public protests; and/or (5) absence of well-defined and enforced private property rights. Considering these conditions in the Icelandic and Faroese contexts, one reason why the cruise industry appears to have a weaker social license in the Faroes than in Iceland, could be the perception that it is not delivering net economic benefits to the society. Also, the significant mistrust between the local community and the industry regarding the whale killing is likely to play a significant role. For SLO to maintain relevance and legitimacy, it needs to consider all stakeholder perspectives seriously. From the passenger perspective, their responses reflect a respectful attitude towards the local communities they visit, and a keen interest in connecting with and experiencing these communities, yet the reality of these cultural exchanges is sometimes not very pleasant, not for the local communities, and not for the cruise passengers, as the case of the whale killing so clearly exemplifies.

Flow and circulation of perspectives is critical to avoid protest, antagonism, and embedded views. Furthermore, for sustaining SLO in different tourism context research show (Baumber et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Douglas et al., Citation2022) that local acceptance, transparency and proactive engagement is critical. It is therefore of vital importance that cruise lines seek feedback from both passengers and local residents. The current gap in awareness of the ‘other’ perspective and a lack of understanding as to how policy decisions are made poses significant challenges in terms of coordination and planning. That lack of circulation is not just in information but also on what drives current decisions. Trust is built up when all parties are more aware of those motivations or perspectives that each party has. SLO may be the stimulus to find appropriate platforms or settings for such exchanges.

7. Conclusion

Cruise ship tourism is changing the nature of Arctic tourism from being predominantly locally owned small and medium sized enterprises to non-regionally owned, reflecting the presence of global economic drivers in Arctic local settings. The attitudes and perceptions of stakeholders directly benefiting from the cruise industry essentially focus on its economic dimension, and thus indicate a high level of acceptance. Non-benefitting stakeholders exhibit a lack of acceptance, showcasing varying attitudes towards cruise tourism. This disparity highlights the challenge of determining what might constitute a SLO. The biggest challenge for local communities is to understand the cruise companies’ business model and consider how the local stakeholders may contribute more proactively towards filling the gap around local knowledge for the cruise visitors. It is likewise important for the cruise companies to enhance their understanding of how their passengers and local communities experience ship arrivals. Thus, co-create sustainable solutions. Currently, what occurs in many of the Arctic ports is mass arrivals at similar times of day/month where the visitors have limited awareness of an individual destination. SLO has the potential to bring these different positions and stances together where currently there is a lack of exchange or appreciation.

The perception of SLO in cruise tourism is shaped by the diverse interests, values, and experiences of the different stakeholders. Achieving and maintaining the SLO therefore requires a holistic approach that promotes a balance between economic benefits and environmental protection, cultural preservation, and community empowerment. By fostering mutual understanding, trust, and collaboration among stakeholders, cruise tourism can contribute to sustainable development and positive social outcomes. However, addressing the complex challenges associated with the development of cruise tourism requires ongoing dialogue, collaboration, and adaptive management strategies. Future research should therefore focus on exploring practical approaches for enhancing SLO in tourism and evaluating their effectiveness in diverse destination contexts.

Acknowledgments

This paper forms a part of a larger project titled Global drivers, local consequences: Tools for global change adaptation and sustainable development of industrial and cultural Arctic “hubs” (https://projects.luke.fi/arctichubs/), sponsored by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 869580. Our stakeholders’ participants both in Ísafjörður and Tórshavn, as well as our cruise passengers, are furthermore gratefully acknowledged for their participation. Further thanks are to Michaël V. Bishop for the location map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baumber, A., Scerri, M., & Schweinsberg, S. (2019). A social licence for the sharing economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 146, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.05.009

- Baumber, A., Schweinsberg, S., Scerri, M., Kaya, E., & Sajib, S. (2021). Sharing begins at home: A social licence framework for home sharing practices. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103293

- Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Nygaarrd, C. A. (2022). Regenerative tourism: A conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tourism Geographies, 25(4), 1026–1046. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2022.2044376

- Bickford, N., Smith, L., Bickford, S., Bice, M. R., & Ranglack, D. H. (2017). Evaluating the role of CSR and SLO in ecotourism: Collaboration for economic and environmental sustainability of arctic resources. Resources, 6(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6020021

- Bogadóttir, R., & Olsen, E. S. (2017). Making degrowth locally meaningful: The case of the faroese grindadráp. Journal of Political Ecology, 24(1), 504–518.

- Bogason, Á., Karlsdóttir, A., Broegaard, R. B., & Jokinen, J. (2021). Planning for sustainable tourism in the Nordic rural regions: Cruise tourism, the right to roam and other examples of identified challenges in a place-specific context. Nordic Council of Ministers, Nordregio Report, 2021, 1. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1517232&dswid=-2892

- Bystrowska, M., & Dawson, J. (2017). Making places: The role of Arctic cruise operators in ‘creating’ tourism destinations. Polar Geography, 40(3), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2017.1328465

- Clark, R. (2023). Cruise liners should apologise to faroe Islanders. The spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/cruise-liners-should-apologise-to-faroe-islanders/

- Cornwall, A., & Jewkes, R. (1995). What is participatory research? Social Science and Medicine, 41(12), 1667–1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00127-S

- Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism. Sustainability, 8(5), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050475

- Dashwood, H. S. (2012). CSR norms and organizational learning in the mining sector. Corporate Governance the International Journal of Business in Society, 12(1), 118–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701211191373

- Douglas, J., Owers, R., & Campbell, M. L. (2022). Social licence to operate: What can equestrian sports learn from other industries? Animals, 12(15), 1987. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12151987

- Dredge, D. (2022). Regenerative tourism: Transforming mindsets, systems and practices. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2022-0015

- Dumbrell, N. P., Adamson, D., Zuo, A., & Wheeler, S. A. (2021). How do natural resource dependent firms gain and lose a social licence? Global Environmental Change, 70, 102355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102355

- Eijgelaar, E., Thaper, C., & Peeters, P. (2010). Antarctic cruise tourism: The paradoxes of ambassadorship, “last chance tourism” and greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653534

- Goodwin, H. (2012). Responsible tourism – using tourism for sustainable development. Goodfellow Publishers Ltd.

- Hall, M. (2019). Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1560456

- Hansen-Magnusson, H., & Gehrke, C. (2023). Navigating towards justice and sustainability? Syncretic encounters and stakeholder-sourced solutions in Arctic cruise tourism governance. The Polar Journal, 13(2), 216–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2023.2251225

- Haworth, J. (2023). Cruise line apologizes after dozens of whales slaughtered in front of passengers. Abc News. Retrieved July 14, 2023, from https://abcnews.go.com/International/dozens-whales-slaughtered-front-cruise-passengers-company-apologizes/story?id=101271543

- Hayward, C., Simpson, L., & Wood, L. (2004). Still left out in the cold: Problematising participatory research and development. Sociologia Ruralis, 44(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00264.x

- Heikkinen, H. I., Bjørst, L. R., & Pashkevich, A. (2021). Challenging tourism landscapes of Southwest Greenland: Identifying social and cultural capital for sustainable tourism development. Arctic Anthropology, 57(2), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.3368/aa.57.2.212

- Henryson, H. A. (2021). Hvað er samfélagsábyrgð? [What is social responsibility?]. Vísindavefurinn [The Icelandic Web of Science]. https://www.visindavefur.is/svar.php?id=76745

- Hoarau-Hemstra, H., Wigger, K., Olsen, J., & James, L. (2023). Cruise tourism destinations: Practices, consequences and the road to sustainability. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 30(2023), 100820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2023.100820

- Howitt, O. J., Revol, V. G., Smith, I. J., & Rodger, C. J. (2010). Carbon emissions from international cruise ship passengers’ travel to and from New Zealand. Energy Policy, 38(5), 2552–2560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.12.050

- Ísafjörður town. (2024). Cruise ships (list of cruise ship arrivals 2022 and 2024). https://www.isafjordur.is/is/thjonusta/samgongur/hafnir/skemmtiferdaskip

- James, L., Smed Olsen, L., & Karlsdóttir, A. (2020). Sustainability and cruise tourism in the Arctic: Stakeholder perspectives from Ísafjörður, Iceland and Qaqortoq, Greenland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1425–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1745213

- Jenkins, H., & Yakovleva, N. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in the mining industry: Exploring trends in social and environmental disclosure. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(3–4), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.10.004

- Jijelava, D., & Vanclay, F. (2018). Legitimacy, credibility and trust as the key components of a social licence to operate: An analysis of BP’s projects in Georgia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140(3), 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.070

- Johnston, M. E., Dawson, J., & Maher, P. T. (2017). Strategic development challenges in marine tourism in nunavut. Resources, 6(3), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6030025

- Lesser, P., Gugerell, K., Poelzer, G., Hitch, M., & Tost, M. (2021). European mining and the social license to operate. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(2), 100787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.07.021

- Lundén, A., Varnajot, A., Kulusjärvi, O., & Partanen, M. (2023). Globalised imaginaries, arctification and resistance in Arctic tourism – an arctification perspective on tourism actors’ views on seasonality and growth in Ylläs tourism destination. The Polar Journal, 13(2), 312–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2023.2241248

- Matthíasson, T. (2003). Closing the open sea: Development of fishery management in four Icelandic fisheries. Natural Resources Forum, 27(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8219.00065-i1

- McGaurr, L., & Lester, E. (2017). Environmental groups treading the discursive tightrope of social license: Australian and Canadian cases compared. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3476–3496. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6566

- Moffat, K., Lacey, J., Zhang, A., & Leipold, S. (2016). The social licence to operate: A critical review. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, 89(5), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpv044

- Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 22(1), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.129

- Murphy, K. J., Griffin, L. L., Nolan, G., Haigh, A., Hochstrasser, T., Ciuti, S., & Kane, A. (2021). Applied autoethnography: A method for reporting best practice in ecological and environmental research. Journal of Applied Ecology, 59(11), 2688–2697. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14252

- Orams, M. B. (2010). Polar yacht cruising. In M. Lück, P. T. Maher, & E. J. Stewart (Eds.), Cruise tourism in polar regions: Promoting Environmental and Social Sustainability? (pp. 13–24). Routledge – Taylor & Francis Group.

- Owen, J. R., & Kemp, D. (2013). Social licence and mining: A critical perspective. Resources Policy, 38(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.06.016

- Ponsford, I. F., & Williams, P. W. (2010). Crafting a social license to operate: A case study of Vancouver 2010‘s cypress olympic venue. Event Management, 14(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599510X12724735767516

- Priatmoko, S., Kabil, M., Purwoko, Y., & Dávid, L.D. (2021). Rethinking sustainable community-based tourism: A villager’s point of view and case study in pampang village, Indonesia. Sustainability, 13(6), 3245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063245

- Prno, J., & Slocombe, D. S. (2012). Exploring the origins of ‘social license to operate’ in the mining sector: Perspectives from governance and sustainability theories. Resources Policy, 37(3), 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2012.04.002

- Ren, C., James, L., Pashkevich, A., & Hoarau-Heemstra, H. (2021). Cruise trouble. A practice-based approach to studying Arctic cruise tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100901

- Riendeau, E. (2023). Setting course for sustainability – evaluation the social carrying capacity of cruise tourism in Ísafjörður, Iceland [ Master Thesis Coastal Management Program]. University of Akureyri/University center of Westfjords.

- Robertsen, R., Eriksen, K., Iversen, A., Nygaard, V., Lidestav, G., Miettinen, J., Suopajärvi, L., Tikkanen, J., Tuulentie, S., Edvardsdóttir, A. G., Ólafsdóttir, R., Elomina, J., Zivojinovic, I., Lindau, A., Pedersen, K.L., Engen, S., Rikkonen, T., Inkilä, E., Pedersen-Lynge, K., & Bogadottir, R. (2024). Gaining and sustaining social licence to operate (SLO) in natural resource-based industries in the European Arctic. ArcticHubs -project, NOFIMA.

- Roque, A., Wutich, A., Brewis, A., Beresford, M., Landes, L., Morales-Pate, O., Lucero, R., Jepson, W., Tsai, Y., Hanemann, M., Water Equity Consortium, A. F., & Action for Water Equity Consortium. (2024). Community-based participant-observation (CBPO): A participatory method for ethnographic research. Field Methods, 36(1), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X231198989

- Salim, E., Ravanel, L., & Deline, P. (2023). Does witnessing the effects of climate change on glacial landscapes increase pro-environmental behaviour intentions? An empirical study of a last-chance destination. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(6), 922–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2044291

- Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1932–1946. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1779732

- Simonsen, M., Gössling, S., & Walnum, H. J. (2019). Cruise ship emissions in Norwegian waters: A geographical analysis. Journal of Transport Geography, 78, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.05.014

- Statistics Iceland. (2024). Population by urban nuclei, sex and age 1 January 1998-2024. https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__2_byggdir__Byggdakjarnar/MAN030101.px

- Statistics Faroe Islands. (2024). Population by sex, age, residency and months (1985-2024). https://statbank.hagstova.fo/pxweb/fo/H2/H2__IB__IB01/fo_abgd_md.px/table/tableViewLayout2/

- Stonehouse, B., & Snyder, J. (2010). Polar tourism: an environmental perspective (Vol. 43). Channel View Publications.

- Suopajärvi, L., Viken, A., Svensson, G., & Pettersson, S. (2020). Social licence to operate: Is local acceptance of economic development enhancing social sustainability? InJ. McDonagh (Ed.), Sharing knowledge for land use management: Decision-making and expertise in Europe’s Northern periphery (pp. 144–159). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Thomson, I., & Boutilier, R. G. (2011). Social license to operate. In P. Darling (Ed.), SME mining engineering handbook (3rd ed., pp. 1779–1796). Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration.

- Thomson, I., & Boutilier, R. G. (2020). What is the social license?. https://socialicense.com/definition.html

- Tuulentie, S., Halseth, G., Kietäväinen, A., Ryser, L., & Similä, J. (2019). Local community participation in mining in Finnish Lapland and Northern British Columbia, Canada – practical applications of CSR and SLO. Resources Policy, 61(2019), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.01.015

- Visit Faroe Islands. (2023). Annual report 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2023, from https://issuu.com/visitfaroeislands/docs/a82583-vfi-_rsfr_grei_ing2022-en-spread

- Williams, P. W., Gill, A. M., Marcoux, J., & Xu, N. (2012). Nurturing “social license to operate” through corporate-civil society relationships in tourism destinations. InC.H.C. Hsu & W.C. Gartner (Eds.), The routledge handbook of tourism research (pp. 196–214). Routledge.

- Williams, P. W., Gill, A. M., & Ponsford, I. (2007). Corporate social responsibility at tourism destinations: Toward a social license to operate. Tourism Review International, 11(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427207783948883

- Zielinski, S., Jeong, Y., & Milanés, C. B. (2021). Factors that influence community-based tourism (CBT) in developing and developed countries. Tourism Geographies, 23(5–6), 1040–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1786156