ABSTRACT

In the last 3 decades, millions of people in India have been impacted by floods, losing billions of dollars in damages. Structural and non-structural flood risk management measures have been adopted abundantly. Yet the damage, although reduced, remains great. Any examination of flood risk management, across a particular geography at any given time, needs to address questions of constraints and power dynamics, that inevitably characterise every decision by each stakeholder involved. An examination of the highly flood-prone state of Kerala, with consecutive floods in the last five years, enables identification of intricate power relations among governments, scientific communities making recommendations, commercial lobbies, political and religious leaders, local influencers and flood-affected communities. The research involves a qualitative methodology with repeated data triangulation across different sources and presents a vivid picture of how policy implementation had been paralysed for years, with scientific recommendations to government bodies being diluted and devalued. To address the existing knowledge gap of understanding decision-making in flood risk management through contextualised power relations and constraints, a hybridisation of power theories and bounded rationality was conducted, developing a framework of Power-Bounded Rationality. The paper identifies how the widely publicised narratives on threatened local livelihoods led to institutional inaction and ultimately, dilution and devaluation of scientific recommendations, resulting in paralysis.

Key Policy Highlights

Since 1990 structural and non-structural flood risk management (FRM) measures have been widely adopted in India and yet flood damage, although reduced, remains great.

Using a hybridisation of power theories and bounded rationality, the research identifies the intricate power relations across governments, scientific communities, commercial lobbies, political and religious leaders, local influencers and flood-affected communities.

The constraints and power dynamics involved are illuminated, showing how policy implementation was paralysed for years and scientific recommendations were diluted.

The paper identifies how the widely publicised narrative on threatened local livelihoods led to inaction by decision-makers, and ultimately, dilution and devaluation of scientific recommendations, resulting in paralysis in FRM.

1. Introduction

Between 1980 and 2017, India faced 278 floods, inflicting losses worth USD 58.7 billion, impacting 750 million people (EM-DAT, Citation2009; UNEP, Citation2020). Floods constitute over half of climate-related disasters in India (Patankar, Citation2020), with the human and economic costs of floods being well established (Mahapatra, Citation2020; Disaster Management Division, Citation2018). Under the national government’s Flood Management Programme, separate funding is available to the individual states in the Indian federal structure (Ministry of Jal Shakti, Citation2019, Citation2022). However, after nearly 75 years of Indian Independence, the first legislation targeted specifically at flood risk management has only recently come into effect: the Dam Safety Act, 2021 (Central Water Commission, Citation2021). Although the infrastructural regulations for flood risk management (FRM) have been accounted for with this Act, the narrative and instructions on FRM are still deeply embedded in the pre-existing general guidelines and government reports on disaster risk reduction (DRR) in India (P. Alex, Citation2019). This necessitates situating the topic of FRM within the wider context of DRR in the nation.

India recognises the need for a proactive rather than a reactive approach, providing for integration of DRR measures in development planning through disaster-related legislation (Government of India, Citation2005), policy (Government of India, Citation2009) and plans (Government of India, Citation2019). However, effective implementation of long-term DRR measures in individual Indian states involves a highly complex network of stakeholders and constraints. Existing approaches that are theoretically robust need to be examined with perhaps the most prominent question in the field of FRM, that repeatedly challenges global, regional and local narratives on the efficacy of existing frameworks: why, then, is the damage so great (White, Citation1942)? The example of Kerala presents a particularly instructive example of Gilbert White’s famous statement: ‘Floods are ‘acts of Gods’, but flood losses are largely acts of man’ (Citation1942, p. 2).

Although great socio-political and economic diversities within the Indian subcontinent characterise FRM in each state, it is necessary to investigate individual and overlapping factors that influence implementation mechanisms within a state, to determine the efficacy of any DRR measure. This paper aims to examine how power dynamics and constraints characterise decisions in Indian flood risk management, to identity when and how paralysis or action occurs. To meet the aim, the research explores the following three critical questions in the Indian context:

How do power dynamics in the Indian federal system impact implementation of DRR and FRM measures?

What kind of constraints determine how power is exercised by various actors in FRM?

What could be the mechanisms to address implementation paralysis of FRM measures and facilitate action?

Power, here, specifically refers to the ability to influence or act. Power is shared between the national and state governments in the Indian federal structure, exercised in several forms. Power relations do not operate in siloes. They impact and are impacted by existing and often ever-increasing constraints on decision-makers. Processes through which decisions on policy implementation and non-implementation or paralysis are reached, are often based on ‘the Politics of Muddling Through’ (Forester, Citation1984, p. 23). Inaction or paralysis in decision-making inevitably inhibits implementation of measures for flood risk reduction.

Paralysis, here, specifically refers to non-implementation. This can result from an inability to act, or choosing not to act, or a combination of both. Its temporal dimension is particularly important in FRM, in the sense that the action needs to happen before the flood occurs. This is the very essence of proactive action, even if that very proactive action is also a reaction of lessons learnt from previous floods in the region, nation or globally. In the Kerala example, paralysis is identified as the non-implementation of environmental regulatory measures in ecologically sensitive areas, that led to increased landslides in the event of floods, resulting in widespread loss of life, livelihoods, and property. The focus of this paper is particularly on the regulatory aspects of FRM, where lack of environmental regulation in the Western Ghats based on scientific recommendations was perceived by a wide range of stakeholders to have significantly worsened flood impact, causing great loss of life and livelihoods.

For a detailed analysis of power dynamics and constraints, necessary for this research, theories of power and bounded rationality were combined, resulting in a theoretical framework of Power-Bounded Rationality. This amalgamation is crucial in examining and explaining power dynamics in Indian FRM, in light of the constraints under which the power dynamics operate. The events in Kerala are particularly illuminating, enabling general conclusions to be drawn, that can inform FRM in India and beyond. Such conclusions may be of particular value where resources are limited, aspirations are high, and living with floods often becomes an inevitable choice.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Bounded rationality

Bounded rationality, first proposed by Simon, acknowledges limitations of cognitive capacities, information gaps and time constraints affecting rationality (Simon, Citation1955, Citation1956, Citation1987, Citation1982). Gigerenzer and Selten (Citation2002) observe that models of bounded rationality describe heuristic processes and classes of environments in which judgments or decisions are reached, rather than just the outcomes of decisions. Bounded rationality and risk assessment are used significantly in flood hazard analysis by Kates (Citation1962), White et al. (Citation2001) and Fischer (Citation2019), facilitating an elaborate understanding of how agents make choices, often accepting greater risks within a certain level of awareness, as opposed to choices which are more rationally founded.

Viale argues that human beings inhabit a world characterised by ‘complexity, recursivity, non-linearity and uncertainty’ and consequently, the rationality of choices is valued according to their adaptability to the environment and use in solving problems (Citation2021, p. 24). This research uses bounded rationality here to show how constraints shape power dynamics and hence, decision-making. It draws upon an important study by John Forester (Citation1984), who argues that under bounded rationality, public administrators and decision-makers habitually have to consider politically-structured practical constraints that determine the course of their decisions. Forester shows how decision-making takes place in an environment that is not only cognitively bounded, but socially differentiated as well.

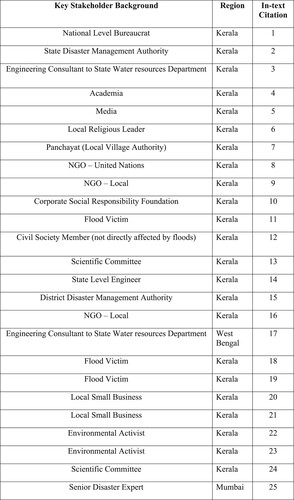

What Forester terms ‘interpersonal manipulation’ (), including ‘wilful unresponsiveness’, characterises and contributes to the ‘structural legitimation’ of implementation paralysis of flood risk management protocols. It is this theoretical approach of Forester that has been chosen for this research, to enable a more nuanced understanding of power relations among different actors in Indian FRM.

Figure 1. Table Showing Forester’s Distinguishing Bounds Upon Administrative and Planning Action. Adapted from Table 1; Forester, Citation1984, p. 25. © John Wiley & Sons, 1984.

2.2 Power theories

Over time, power has been envisaged in different ways by Weber (Citation1947), Lukes (Citation2005), Ailon (Citation2006), Allen (Citation2009), Foucault (Citation1982), Foucault et al. (Citation2020) and very many others, enabling definitions of relations between a variety of actors. Depending on the case and context, such actors involve governments, non-governmental organisations, political parties, religious groups, civil society, private lobbies, interest groups (Penning-Rowsell & Johnson, Citation2015), the media and others.

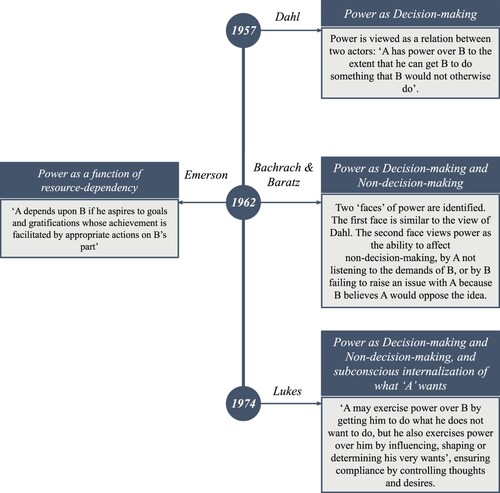

Choice of definition of power for any research is indeed an intellectual exploration of one’s own positionality and socio-political identity, rooted in lived experiences. Given the author’s ethnographic, socio-political and cultural embeddedness in Indian society, the four conceptualisations of power explored in Self and Penning-Rowsell (Self & Penning-Rowsell, Citation2018) seem the most relevant in explaining the power dynamics in Indian FRM. As the Kerala example shows, these four power theories can provide some useful guidance on understanding the exercise of power in its different forms, by a range of decision-makers, operating under varying constraints. Despite the time, place, case and context, these four conceptualisations help draw general conclusions that can be further tested and examined for other examples.

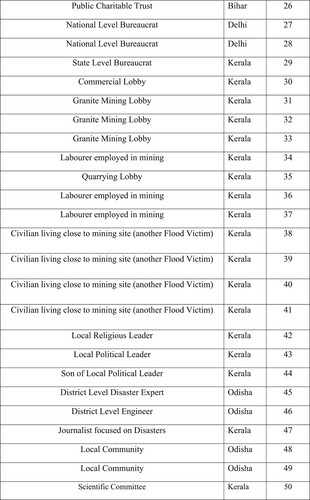

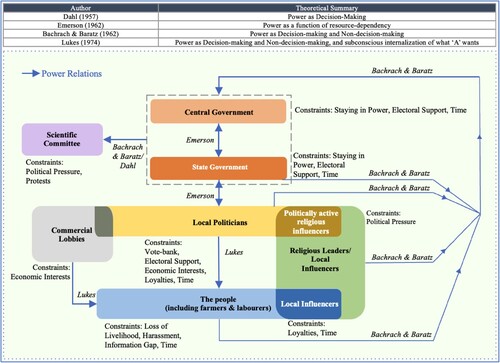

This research innovatively combines four conceptualizations of power, as elucidated by Self and Penning-Rowsell (Citation2018), with Forester’s model of ‘Bounded Rationality and the Politics of Muddling Through’ (Citation1984), to assess how constraints and power are interdependent in Indian FRM. This hybrid framework constructed for the purpose of this research is termed as ‘Power-Bounded Rationality’, to emphasise the intricate bounds of power that characterise rationality. This effectively enables identification of reasons behind paralysis in implementation of DRR and FRM measures, which, as observed in Kerala, were regulatory measures limiting environmental exploitation by mining lobbies in ecologically sensitive areas of the Western Ghats. Unsurprisingly, such areas have witnessed increased landslides during recurrent floods, claiming lives and livelihoods. The four primary theories of power selected for this research, and as explored in Self and Penning-Rowsell (Citation2018), are presented in .

Figure 2. Summary of the four power theories chosen for this research, as conceptualised by Dahl (Citation1957), Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1962), Lukes (Citation2005) and Emerson (Citation1962).

While different authors use the term ‘theory’ in different ways, this research uses power theories to help interpret the decisions made by a diverse range of stakeholder groups, and constraints identified under bounded rationality, to further explain why such decisions were made in those respective circumstances under the existing constraints. The four power theories help classify the different ways that power is exercised into four broad categories, while the constraints, characterising the respective circumstances in which power is exercised, are identified following John Forester’s (Citation1984) development of bounded rationality. under the Methods section further explains how this framework has provided guidance on systematically analysing the empirical data collected.

3. Knowledge gap

This research specifically targets two kinds of knowledge gap – the theoretical, and the empirical.

3.1 Theoretical contribution

The theoretical contribution is an amalgamation of two sets of ideas which this research has shown to be inextricably linked, such that one dimension alone is insufficient to understand the full complexities of flood risk management. A hybridisation of the four power theories by Dahl (Citation1957), Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1962), Lukes (Citation2005) and Emerson (Citation1962), as selected by Self and Penning-Rowsell (Citation2018), with Forester’s (Citation1984) bounded rationality helps examine the many nuanced layers of power interplay amidst constraints. Such a hybridisation formed a theoretical magnifying glass for the exceedingly complex Indian circumstances of federal decision-making, which can be a useful tool for examining and learning from different, contextualised interplays of power and constraints across other nations.

Generous attempts have been made at understanding decision-making for flood risk management using an abundance of methodologies and approaches (Beven & Hall, Citation2014; De Brito & Evers, Citation2016; Hall et al., Citation2003; Hall & Solomatine, Citation2008; Levy, Citation2005; Maskrey et al., Citation2021; Pham et al., Citation2021; Porter & Demeritt, Citation2012; Sayers et al., Citation2013; Tyler et al., Citation2021; Woodward et al., Citation2011). Literature on flood risk management, particularly in the Indian context, has focused greatly on flood risk assessment (Ghosh & Kar, Citation2018; Islam & Ghosh, Citation2022; Roy et al., Citation2021; Tomar et al., Citation2021), with a multi-criteria approach for decision analysis being popular (Roy et al., Citation2017; Mishra & Sinha, Citation2022), particularly while addressing the socio-economic challenges (Pathan et al., Citation2022; Yazdani et al., Citation2019). But flood risk management goes much beyond risk assessment and scientific knowledge, into the realm of the socio-political, where individuals and groups, despite being informed of the scientifically ‘right’ thing to do, are bounded by constraints, in an intricate interplay of power with other individuals and groups.

Penning-Rowsell and Johnson (Citation2015) acknowledge the ‘ebb and flow of power’ in British flood risk management, while Begg (Citation2018) further adds a layer of justice to power in European flood risk management. Globally, studies on understanding power have majorly focused on developed nations (Bubeck et al., Citation2017; Butler & Pidgeon, Citation2011; Ingold & Gavilano, Citation2019; Rasmussen et al., Citation2021; Thaler & Levin-Keitel, Citation2016). Specifically in the Indian context, given the political nature of the topic and, of course, its scientific relevance, it is not surprising to see ‘power’ in flood risk management being analysed more in its electric sense (Kumar et al., Citation2019; Saha & Agrawal, Citation2020). Power, in its socio-political sense, has rarely been investigated in Indian flood risk management.

But in the quest to select a suitable theory to best address the empirical data of this research, no power theories on their own adequately accommodate the ever-present and pressing constraints under which decisions are made by different stakeholders. Birkholz et al. (Citation2014) revisit theoretical developments that have guided understandings of flood risk management and flood risk perception, where the works of Kates on bounded rationality feature widely. But they, too, while addressing bounded rationality, do not treat the theme of power adequately in understanding how the perception of risk itself is shaped by power dynamics, as the empirical evidence from this research shows.

This necessitated an evaluation of the evolution of bounded rationality, where the development by John Forester (Citation1984) seemed most appropriate to explain the ‘politics of muddling through’, which was a characteristic trait observed in most decision-makers from the field data. The theoretical framework, thus, not only helps analyse decisions by governments, scientific committees and other lobbies involved, but also those taken by the communities at risk, to contribution to the literature on risk perception, and why communities choose to live with risk as the works of Kates have highlighted. This process of developing a hybrid theoretical framework was a reiterative process following multiple rounds of empirical evidence gathering and revisiting theories to best analyse the evidence gathered.

3.2 Empirical evidence

This research is grounded in an interesting case where there is a clear involvement of national, state and local actors in science-policy-implementation interactions. Implementation is taken as separate and distinct from policy-making, because theoretically sound policies encounter practically challenging situations under varied contexts. In the field of flood risk management, empirical data has greatly been used for understanding flood risk perception and its implications (Baan & Klijn, Citation2004; Bradford et al., Citation2012; Lechowska, Citation2018), modelling (Nkwunonwo et al., Citation2020), planning (van Herk et al., Citation2011), and public acceptance (Buchecker et al., Citation2016). Systematic reviews of empirical research help identify a broad range of themes addressed through empirical evidence (Bubeck et al., Citation2017; Kellens et al., Citation2013; Sadiq et al., Citation2019). But to date, no research exists in the field of flood risk management, that has analysed the empirical evidence through the prism of power theories and bounded rationality so as to examine the different stages, levels, changes and deferrals in decision-making to implement scientific recommendations for environmental regulation to mitigate flood impacts.

The case of Kerala provides evidence to draw out specific stages of decision-making in the evolution, and then progressive dilution, of scientific recommendations, in an attempt to maintain political gains, where the status quo remained unchallenged resulting in a long-term paralysis or inaction. This detailed empirical research thus illustrates how a framework of Power Bounded Rationality can be applied to a real-life scenario. This helps identify who holds power, when, where and how that power interacts with existing constraints, and if such interactions result in action or paralysis in implementation of flood risk management measures.

4. Methodology

4.1. Case study justification

4.1.1 Choice of Kerala

The Indian state of Kerala is chosen because the understanding of the impact of the Kerala floods over the last five years (2018–2022), is located within a discourse concerning the state’s non-implementation of scientific reports against development activities and illegal mining in the ecologically sensitive Western Ghats (Gadgil, Citation2020; Joseph, Citation2019; Padma, Citation2018; Sinha, Citation2018). Differing responses at various governance levels and in public sentiment lead to virtually no risk reduction action being taken over time (Raman, Citation2020), resulting from what is considered here as ‘implementation paralysis’. The Kerala example emphasises larger challenges of power, decision-making and implementation in the field of FRM, particularly in the context of shared power in federal systems.

4.1.2 Impact of floods in Kerala

In 2018, Kerala faced disastrous, almost once-in-a-century floods (Reliefweb, Citation2018). At least 70 landslides were recorded, particularly in ecologically sensitive areas in the mountainous region of the Western Ghats where quarrying, construction, large-scale cultivation and deforestation had been permitted, resulting in major mud-slips (Raghunath, Citation2019). The official death toll was 483, with damages estimated at over USD 3 billion (The New Indian Express, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Choudhary, Citation2018).

Floods hit Kerala again in 2019, claiming 121 lives (India Today, Citation2019). The public recalled the need for environmental protection in the Western Ghats to reduce such devastating impacts of floods (The Hindu Businessline, Citation2019). In 2020, floods hit again causing loss of 52 lives in one district alone owing to landslides (BBC, Citation2020; News18, Citation2020). Development activities were questioned again (BBC News, Citation2020). In 2021, Kerala’s very recent history repeated itself, with 42 reported deaths, and damages exceeding USD 25 million (Rajagopal & Mishra, Citation2021). Floods in Kerala in 2022 continued to claim lives and livelihoods (Caritas Citation2022). Although, at a glance, the tide seems to be turning in Kerala, with the number of officially reported casualties coming down over the years, the damage, deaths and displacement, still remain too significant to be ignored (Indian Express, Citation2022; Jacob, Citation2022; Mathrubhumi, Citation2022; Onmanorama, Citation2022) .

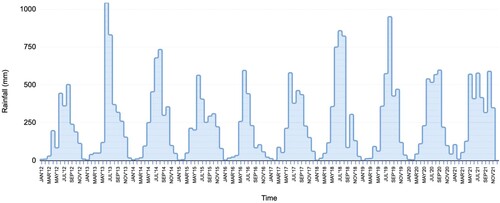

Figure 3. The figure represents monthly rainfall in Kerala across the time period of January, 2012 to November, 2021, with data collected from the Customized Rainfall Information System (CRIS) under the Hydromet Division of the Indian Meteorological Department (Citation2020) and onmanorama.com/news/kerala.

4.2 Data collection

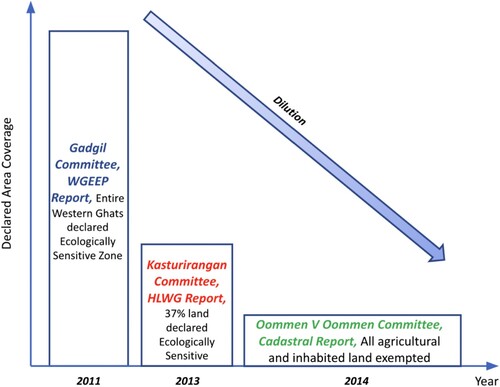

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Quantitative compilation of Indian Meteorological Department rainfall data was followed by a study of flood situation reports published by the Disaster Management Division, and scientific reports on the need for environmental regulation in the flood-prone Western Ghats from expert committees headed by Madhav Gadgil (WGEEP, Citation2011), K.R. Kasturirangan (HLWG, Citation2013) and Oommen V. Oomen et al. (Citation2014). These three crucial reports are explored, in light of the complex power dynamics and constraints operative upon different decision-making stakeholders.

An extensive body of media reports and government records spanning 2011–2022 were collected through digital archival research. A wide range of relevant stakeholders were identified and mapped through an evaluation of such reports, along with government websites. At the initial stage, purposive sampling (Palinkas et al., Citation2015) was used to identify the key decision-makers in the national, state and district governments who are in charge of policy-making and implementation in disaster management, planning and prevention in India, with a particular focus on flood impact mitigation.

In Kerala, flood-affected civilians were identified, from diverse socio-economic, political and cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, the term ‘stakeholders’ in this research also included anyone with a stake in the environmental regulation of the Western Ghats, such as commercial lobbies, and more specifically, granite mining bodies. Individuals or groups influencing implementation or non-implementation of environmental regulatory measures with religious, political and economic interests were also identified. Data triangulation through primary qualitative research with different stakeholder groups enabled an in-depth understanding of how continued natural exploitation, particularly granite mining in Kerala, severely aggravated the impact of floods through heavy landslides over the last 5 years, from 2018 to 2022.

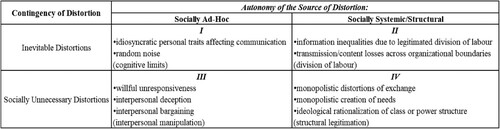

Purposive sampling (Robinson, Citation2014) enabled identification of the most relevant stakeholders who either impact, or are impacted by, decisions on environmental regulation and FRM in Kerala. However, once these different groups of stakeholders were identified, random sampling was necessary in selecting flood victims, the sheer number of whom is so great that it was not possible to include everyone. Snowball sampling at every stage of data collection enabled inclusion of any stakeholder who may not have gained visibility during the extensive literature review, and study of institutional and media reports (Tansey, Citation2007). A total of 49 stakeholders were chosen to ensure sectoral diversity.

The Social Research Association Ethics Guidance (SRA, Citation2003, Citation2021) was followed for this research. Each stakeholder has been anonymised to ensure they felt secure to share information, and was repeatedly reminded in their preferred language that they can withdraw consent at any point, even after having provided information. Written permission was obtained for direct quotations. Information was collected in a structured manner, with reflexive data triangulation at every stage to identify the commonalities and differences in the discourses of institutional decision-makers, commercial lobbies, scientific groups, religious and political leaders, local influencers, farming communities, flood victims, NGOs, media bodies and academics. Recordings were made where allowed, but the protection and anonymity of sources was prioritised at every step. The language of communication included English, Hindi and Malayalam, to ensure that individuals, not speaking Hindi or English, particularly prevalent amidst flood victims, were also included in the research.

To understand power dynamics, the gathering of information focused on identifying who has the most power in Indian FRM, how they exercise that power, and what the consequences are. This enabled identification of existing constraints and resultant paralysis of action. The three critical aspects of power dynamics, constraints and implementation paralysis in FRM explored in this research are further contextualised through the Kerala example, with a host of specific, targeted questions on where and how non-implementation of scientific recommendations for environmental regulation occurred; if implementation paralysis of such recommendations aggravated flood impact from 2018 to 2022; what kind of power relations and constraints led to such paralysis, and what mechanisms can address implementation paralysis in FRM.

It became crucial to analyse who exercised what kind of power to influence the non-implementation of scientific reports that recommended reduction in mining and quarrying activities in the Western Ghats. The constraints under which such decisions were made were also identified, to understand if, how and where paralysis occurred, leaving thousands vulnerable to aggravated landslides during floods. The relation between environmental regulation and exacerbated flood impacts was observed in the narratives of the governing and the governed; the influencing and the influenced .

Figure 4. Stakeholders from Kerala and other Indian States. Stakeholders have been arranged in order of the dates of information gathering (from 13.12.2020 to 05.10.2022).

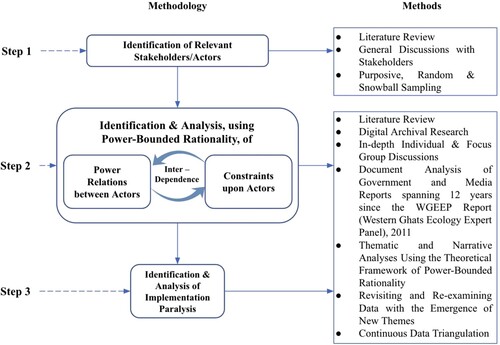

4.3. Qualitative data analysis

The data analysis was guided by the hybrid theoretical framework of Power-Bounded Rationality, developed specifically for this research. A three-step methodology was designed with the theoretical framework in mind. elucidates each step with the specific methods deployed for data collection and analysis.

Figure 5. Summary of the 3-Step methodology constructed for this research, using the hybridised theoretical framework of Power-Bounded Rationality, and the individual methods deployed for data collection and analysis.

Step-1 of the methodology focused mainly on the identification of relevant stakeholders. Although it is difficult to exhaustively identify every stakeholder, this step was elaborate, and revisited multiple times until the research was concluded to ensure every potential actor or at least actor groups, such as scientific committee or commercial lobbies has been identified. If one limitation was the inability to include everyone, the research was strengthened by the inclusion of many diverse groups of stakeholders. Literature review and general discussions with stakeholders were followed by purposive, snowball and random sampling methods. More stakeholders were identified and included as new media reports came out in 2020, 2021 and 2022.

Step-2 of the methodology deploys collection and analysis of information, identifying and specifically locating power relations amongst stakeholders and the different kinds of constraints operative on them. The analysis has three aspects: first, identifying power relations amongst stakeholders; second, going deeper into the constraints operative upon those stakeholders; and third, understanding how power relations and constraints impact each other. To clarify, existing constraints impact decisions that in turn, both affect and effect power relations, which lead to further constraints. Such a theoretical distillation of the information gathered enabled establishing the inter-dependence between power relations and constraints in a cyclical model where they impact and compound each other. This cycle of inter-dependence is pointed out in Step 2 of . The narratives and dominant discourses of individuals within, and across different stakeholder groups, were analysed, guided by the theoretical framework that remained focused on the identification and categorisation of different power relations using the four power theories highlighted in Self and Penning-Rowsell (Citation2018), and the identification of constraints through Forester’s development of bounded rationality. The analysis was revisited and further refined in 2021 and 2022, after the first phase of research in 2020. Data triangulation and corroboration was done even during data analysis, although those discussions were not included once data saturation was reached.

Step-3 of the methodology draws upon Step-2, and locates where paralysis occurred to effect non-implementation of environmental regulation measures, and examines the impact of such paralysis in the event of floods. The findings of Step-2 on power relations and constraints were further explored, to understand if and how paralysis is currently perceived by different stakeholders in light of the floods, and what is the way forward. Narratives on existing paralysis and potential ways to effect proactive action were the primary focus of this final step of the methodology. Individual and collective narratives of different stakeholder groups were analysed to highlight avenues for action, learning from the consequences of prolonged paralysis or lack of action.

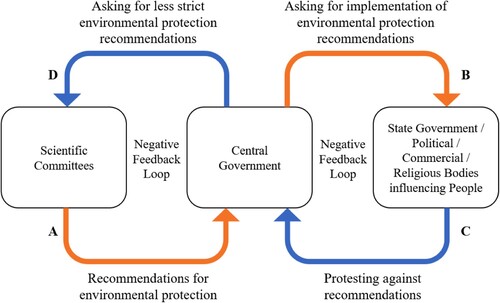

The results of this 3-step methodology are represented in an intricate diagrammatic synopsis in . A negative feedback loop (Lidwell et al., Citation2003; Rosney, Citation1979) rounds up the research in by further explaining how implementation paralysis occurred in FRM through resistance to change.

5. Results

This section is divided into two sub-sections: the first identifies action and paralysis in flood risk management in Kerala, and how these two concepts are perceived by different stakeholders; the second part presents an in-depth analysis of the empirical evidence to illustrate how the theoretical framework of Power Bounded Rationality helps identify and explain the different power dynamics, operative constraints and their outcomes on decisions by different stakeholders. These decisions directly impact action or paralysis in implementation of scientific recommendations for environmental regulation that then impact flood risk management and disaster risk reduction in Kerala. It is important to note, however, that as this is qualitative research, the results are an analysis of the stakeholders’ perceptions, substantiated as much as possible with the literature, and government and media reports as available.

5.1 Understanding action and paralysis in FRM and DRR in Kerala

When asked about power in FRM in India, all 50 stakeholders responded with respect to power in reactive disaster response. This exposed the general lack of a specific, institutional focus on proactive FRM, and established the need to first consider flood response to conceptualise power. CommunitiesFootnote1 supported by local (Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Citation2022) and district authorities (Kerala State Disaster Management Authority, Citation2022) are considered to have most power for action in disaster response. Effective capacity building and sensitisation of the village electorate (National Portal of India, Citation2022) by local panchayats (village councils) result in greater action.Footnote2 During the 2018 floods, in areas where this had been properly executed, communities helped local authorities in evacuation, and knew the meaning of colour-graded flood warnings.Footnote3

This was particularly noticeable in the Mullaperiyar panchayat where people were aware of the threats to the Mullaperiyar Dam, over 125 years old. The district and local authorities were well-prepared, engaging the community.Footnote4 The effective community response to the floods gained national and international praiseFootnote5 (Banerji, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Varma, Citation2018). Proactive flood risk reduction was often argued to be in its nascent stage in India by the stakeholders, but the significant improvements in flood response over time was acknowledged widely.Footnote6 Bureaucratic action seemed to succeed where there was effective information flow among officials, elected representatives and local people.Footnote7

With regard to proactive FRM and DRR, it was pointed out that while planning occurred at the state and district levels, policy was guided by the national government.Footnote8 Disaster management plans at national, state and district levels recognise the need for mainstreaming DRR, but this has not been adequately operationalised.Footnote9 In FRM, structural measures such as dam-building and embankments were considered to receive priority,Footnote10 whereas non-structural approaches such as spatial planning and land use regulation enforcement (Parker, Citation2000; Penning-Rowsell and Becker, Citation2019) were considered to be undervalued in favour of meeting development targetsFootnote11 (Kumar, Citation2018). One respondent, being a renowned disaster expert for over 3 decades in India, astutely pointed out, ‘The drivers of development are also the drivers of disaster risk.’Footnote12

In policy implementation, the national government acts through the state government which, in turn, acts through various district administrations bearing in mind regional needs.Footnote13 Bureaucratic efficiency was reported to be progressively hindered in a top-down trajectory owing to increasing political pressures exerted laterally in the state.Footnote14 Competing national and state influences also hindered action at district levels.Footnote15 Bureaucratic initiative, visible in reactive disaster response, was considered to be absent in proactive FRM and DRR measures, as elected politicians and industrial lobbies in the state constrict any space of action by civil servants.Footnote16 This leads to decisions being deferred and ultimately abandoned, as overenthusiasm for FRM measures is not appreciated and can sometimes be met with departmental transfers.Footnote17 Inaction and delay, thus, appear to be safer and effectively non-disruptive options.Footnote18

Paralysis or non-implementation due to constraints involving political pressures, economic interests and lack of public consultation were voluntarily, and repeatedly, pointed out by stakeholders without the word ‘paralysis’ being mentioned to them.Footnote19 However, Stakeholder-25 preferred the word ‘challenges’ to ‘paralysis’, defending the efforts of academics and practitioners for DRR interventions in the country. Gaps in information flow and non-transparency were further highlighted as characteristics of any failure to ensure well-informed communities.Footnote20 Power for action was reported to rest with the local district officers and flood-affected communities in flood response, going from local to general, with the state government intervening into the district, and the national government intervening into the state only upon request for support and mobilisation of resources (NDMA, Citation2009; Pradeep et al., Citation2019). But power dynamics in DRR and FRM, particularly in the context of implementation of scientific recommendations, need particularly close attention, as explored below.

5.2 Power relations, constraints and scientific recommendations in DRR and FRM in Kerala, India

The Kerala example exposes how complex power struggles and constraints of operation of different actors at various levels of decision-making result in implementation paralysis in the case of scientific recommendations. The influence of different stakeholders in FRM, is impacted by such power struggles. This is illustrated in , using power theories. Constraints have been identified following Forester’s bounded rationality framework (Forester, Citation1984).

Figure 6. A diagrammatic representation of the results of this research. The figure demonstrates the complex power dynamics and constraints of actors that led to implementation paralysis in FRM and DRR measures in Kerala, India. The arrows indicate power relations. The sizes of the boxes vary to maintain legibility of in-figure text and do not correspond to the magnitude of power. The table above the figure acts as a summary for the power theories.

The Kerala example also presents a crucial case of how what started as an environmental conservation movement has now become integral to the discourses and narratives on FRM in the region. The Save the Western Ghats Movement (SWGM) started in 1986. After decades of public advocacy for conservation, it was finally in 2010 that the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP), headed by eminent ecologist Madhav Gadgil, was formed, facilitated by the then national government (Peaceful Society, Citation2019; Salim Ali Foundation, Citation2014; WGEEP, Citation2011). Emerson’s power dimension as resource dependency, where power is shared, becomes evident when both national and state governments, and state government and local politicians hold power at the same time, as shown in .

The WGEEP submitted its report to the national government in 2011, recommending phasing out and strict regulation of mining, quarrying and other development activities in most of the Western Ghats (WGEEP, Citation2011). When the national government sent this report to the state government, a ‘campaign of disinformation’ (Gadgil, Citation2014, p. 38) followed.Footnote21 The state government, politicians and politically-active religious representatives ignited widespread protests against the reportFootnote22 (Gadgil, Citation2014; Radhakrishnan, Citation2013; NDTV Thiruvananthapuram, Citation2013). In , Lukes’ power dimension is evident where these actors exercise power over the people, particularly farmers, influencing them to perceive the report as an ‘anti-people’ top-down approach of the national government that threatens their livelihoods.Footnote23 The actual report, however, recommended a bottom-up approach of public consultation, supported by government incentives for best practices (Gadgil, Citation2014).

Regional commercial lobbies have politically-active members with ‘clout’, who further exert Lukes’ power dimension on the people, also as shown in . Such people are mainly labourers, whose livelihoods depend on contractual labour assignments from such lobbies.Footnote24 People operate under maximum constraints of misinformation and fear of loss of livelihoods.Footnote25 Protesting against the report, thus, seemed to them as the safest option.Footnote26

then highlights how Bachrach and Baratz’ power dimension of effecting non-decision-making is applicable when the people, politicians, politically-active religious influencers, and state government together protested against the Gadgil report, putting pressure on the national government for its non-implementation. This resulted in the national government exercising Bachrach and Baratz’ power dimension over the Gadgil scientific committee, thus resulting in implementation paralysis of proactive FRM and DRR measures in the Western Ghats.

The national government then constituted the High-Level Working Group (HLWG, 2013) led by renowned space scientist, K.R. Kasturirangan to evaluate the WGEEP report on environmental protection (WGEEP, Citation2011). The HLWG submitted its report in 2013, diluting scientific recommendations (See ) under political pressure.Footnote27 This shows the national government’s exercise of Dahl’s power dimension over the Kasturirangan scientific committee as illustrated in . When the national government sent this report to the state, the same sequence of power and operative constraints followed for the state government, politicians, politically-active religious influencers, and the peopleFootnote28 (Suchitra, Citation2013). Here, the state government exercises Bachrach and Baratz’ power dimension () over the scientific committee, resulting in non-implementation of its scientific recommendations, and thus, contributing further to implementation paralysis of FRM and DRR measures .

Figure 7. A visual representation of the gradual dilution of scientific reports (HLWG, 2013; Oomen et al., Citation2014; WGEEP, Citation2011).

Figure 8. A Negative Feedback Loop demonstrating how paralysis in implementation of environmental protection measures for FRM and DRR occurred as a result of resistance to change in case of the first two scientific reports in 2011 and 2013. The arrows marked A and B indicate change that can facilitate FRM. The arrows C and D indicate resistance to such change, causing implementation paralysis. The arrows A, B, C and D denote the sequential order of events.

After the implementation paralysis in the first 3 years, in 2014, the state government formed its own committee, led by biologist, Oommen V. Oommen (The Hindu Businessline, Citation2018). Under political pressure, the committee produced the Cadastral Report in 2014, taking all inhabited and cultivated land out of the ecologically sensitive area in the Western Ghats that is severely landslide-prone, particularly due to heavy rainfall and floods (Kerala State Disaster Management Authority, Citation2016; Oomen et al., Citation2014). This shows the state’s exercise of Dahl’s power dimension over the Oommen scientific committee, that finally resulted in abandonment of environmental protection measures, thus pacifying the political-business nexus, using the narrative of protecting people’s livelihoods.Footnote29

The constraints of wanting to stay in power and having electoral support that had resulted in a power handicap and inaction of the national government after the first two scientific reports were ultimately rendered invalid with the government being replaced in 2014 during the national elections, when a different political party assumed power in the national government. The same happened in the state of Kerala, with the Kerala Legislative Assembly election in 2016 resulting in a change in the political party in power, although controversies over the scientific reports continued (Down to Earth, Citation2018).

Paralysis resulted from power dynamics and constraints, but when the 2018 floods hit, the people who were led to believe that implementation of scientific reports would disrupt their lives suffered the most (CABI, Citation2018). Hundreds of thousands of farmers were severely affected and the state incurred agricultural losses worth over USD 800 million (Babu, Citation2019; Kanth, Citation2019; Karun, Citation2019). After the impact of the 2018 floods, the National Green Tribunal ordered the national government to disallow reduction of ecologically sensitive areas in the Western Ghats (Aggarwal, Citation2020; Hindustan Times, Citation2018). All stakeholders, including those from mining lobbies, emphasised in our discussions how the argument of environmental regulations against quarrying and mining in the Western Ghats, particularly granite mining, became integral to almost all discussions, discourses and even local narratives on the devastating impacts of floods in Kerala. The stakeholders from mining and quarrying lobbies, however, denied any relation connecting mining and environmental regulation with aggravated flood impact in the region, despite civilians living close to those sites reporting that landslides during floods worsened after such activities of geological exploitation in the region were carried out.

6. Discussion

From the Kerala example, paralysis as an outcome of power dynamics and decision-making constraints can be identified in three main processes: lobbying, devaluation of scientific opinion, and technological management. These may well hold true for the larger context of FRM and DRR in India as a whole.

To draw out each of these processes, the framework of Power Bounded Rationality became useful to understand what kind of power was exercised to affect and effect decisions, and what constraints characterised the circumstances under which the decisions were made. For example, lobbying as an exercise of power can take different forms. People can be lobbied to take certain action that they otherwise perhaps would not take (Dahl, Citation1957), people can be lobbied to not take action at all (Bachrach & Baratz, Citation1962), people can be lobbied to internalise the wants of others (Lukes, Citation2005) or people can be lobbied through leveraging resource dependency (Emerson, Citation1962). These four generalisations of how power is exercised could classify every series of actions or paralysis occurring in the Kerala example as shown in . But while the four power theories help understand the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of power exercise, the identification of operative constraints that impact decision-makers helps make sense of the ‘why’. Why did they lobby? What could have been the constraints? Similar questions on decisions that effected devaluation of scientific opinion and affected technological management guided this research. Understanding power and constraints brings all decisions down to perhaps the most fundamental question – ‘Why did they do what they did?’ Without addressing this question, one cannot attempt to make sense of paralysis or action, be that in flood risk management or beyond.

However, it is worth noting that while paralysis, in the Kerala case, has been treated as a failure of flood risk management, that might not always be the case. Speaking of damages from floods, White (Citation1942) himself spoke of the levee effect where structural interventions actually increased damages. Refusal to implement flood management protocols, in such examples, may be the more sensible option. In the case of Kerala, it is possible that paralysis also may be in certain cases a sensible option. But that is unlikely in the case of well thought-out, scientifically supported regulatory regimes implemented in consultation with the public. Here, paralysis is undoubtedly a problem.

6.1 Lobbying

Lobbying is a common practice in all political systems, but particularly in developing countries it tends to have a dangerous symbiosis with corruption (Saraf et al., Citation2007). In Kerala, the role of illegal mining, unsustainable farming practices, real-estate development and tourism ventures in increasing environmental degradation is well established (Raman, Citation2020). Of the 6000 active quarries in the Western Ghats region, 2000 are illegal. These were highlighted in the WGEEP, HLWG and Cadastral Reports, but ‘no substantive measures have been taken so far’ (Raman, Citation2020, Footnote 7). The continuance of these practices points to the power of lobbies working to paralyse the legal safeguards already in place and create pressure on decision-makers, leading to rejection of any further environmental protection measures. Ravi Raman, himself a member of the Kerala State Planning Board, acknowledges that in the 2018 flood, most damage was due to landslides caused by illegal resource extraction (Raman, Citation2020). The power of political and commercial lobbies in constraining effective action for DRR is a common social perception.Footnote30

Lobbying in India against environmental regulation with the excuse of livelihood protection is also rampant in other states (OECD, Citation2005; Sarangan, Citation2020; Stuligross, Citation1999), in the face of civil society discourses on how this results in aggravated flood impacts (Khambete, Citation2019). For example, in the devastating Uttarakhand Floods of 2013, unchecked development, particularly involving hydropower projects, was blamed for exacerbated flood impact (Anand, Citation2021; Bidwai, Citation2013; Schneider, Citation2014). Sunita Narain, environmentalist and member of the HLWG for Kerala, also criticised development strategies such as unchecked construction activity, mining and road-building in the context of Uttarakhand Flash Floods (India Today, Citation2013; Narain, Citation2013). The political and industrial lobbies that tend to gain the most from such development activities, rarely come to the forefront, exercising power through financial clout ‘behind the scenes’, as many stakeholders pointed out.Footnote31 The most vulnerable communities, due to both misinformation and a lack of alternatives, often protest against environmental norms, being persuaded that environmental protection will lead to a loss of livelihood.Footnote32 Creating or supposing gaps in the flow of information (Kukreti, Citation2020) is a primary strategy for lobbyists to paralyse effective environmental management that become crucial to managing flood risk.

6.2 Devaluation of scientific opinion

Expert scientific bodies are regularly constituted to aid national and state policy-making, but recommendations that call for greater environmental protection as a safeguard for FRM and DRR meet with opposition at all levels. This is not to say that the ‘science’ is necessarily always good or right, or that scientific committees, groups and lobbies are not capable of having their own biases, agenda and affiliations. The creation of competing scientific bodies to repeatedly revise and progressively dilute recommendations specifically targeted at regulating land use in ecologically sensitive areas, until recommendations are abandoned altogether shows how the devaluation of scientific opinion can happen through scientific bodies themselves, when such bodies reel under political pressures. Continuing scepticism about the importance of credible scientific studies in DRR and FRM is highlighted by the decision of the state of Karnataka, which neighbours Kerala, to reject the HLWG report (2013) on the claims that it is ‘unscientific’ and is opposed by all segments of society (The Economic Times, Citation2020).

Generally, national and state policy-making have long-term goals and sustainability in mind. However, since national and state governments are also subject to political and electoral compulsions, the execution of scientifically viable environmental policy-making has to contend with short-term ‘development’ goals, where the constraints imposed by lobbying become evidentFootnote33 (Sathaye et al., Citation2006). The rejection of the WGEEP report is a clear instance of this, but other examples are seen in the commissioning of industries, land development and dam-building in sensitive areas, against scientific recommendations (Baghel & Nusser, Citation2010; Khanduri et al., Citation2013). Bureaucratic delay is reported in Uttarakhand, for example, where the State Disaster Management Authority did not meet between 2007 and 2013, while a federal audit report released in 2013 noted that 42 hydropower projects were operative, and a further 203 were either being considered for institutional clearance or under construction already (Padma, Citation2013).

The question of perception is crucial here, as the actual content of the reports is often imperfectly communicated to stakeholders.Footnote34 The setting up of rival scientific committees to review and dilute earlier recommendations also leads to an erosion of trust in scientific expertise amidst civil society at large.Footnote35 Thus, the exercise of power through political decision-making in the environmental sector in India comes under pressure from a variety of agents, including groups in civil society, who are persuaded that their best interest lies in paralysing environmental regulation. As explained by Giddens (Citation1990), such paralysis comes about through the devaluing of science, creating specific deficits of trust in expert systems.

6.3 Technological management

Much of the debate about the Kerala floods has also been about the role of dams in failing to meet the challenges of the extreme rainfall events in the Western Ghats. Dam management in India requires separate research, but a few aspects relevant to the study of power and paralysis are mentioned here. Dams in India have historically served the twin purposes of irrigation and power generation (Bandyopadhyay et al., Citation2002). As such, they had been a mainstay of development initiatives, with scant regard for environmental costs incurred.Footnote36 Both the WGEEP report and the HLWG report proposed restrictions on dams, but action remained inadequate (WGEEP, Citation2011; HLWG, 2013).

After the 2018 floods, the Central Water Commission released a report in September 2018 asserting that dams had no role in aggravating flooding, and placed the blame on heavy rainfall (Central Water Commission, Citation2018, Citation2021). This contradicted a NASA report that initially observed that the deluge could have been partly contained if the dams were opened in a systematic manner (Elliot, Citation2018). However, NASA later revised the report recommending more thorough analysis into the issue (NASA Earth Observatory, Citation2018). A public interest suit filed in the Kerala High Court led to the amicus curiae in the case, reporting that poor management increased flood damage as ‘none of the 79 dams in the State were operated or used for the purpose of flood control/moderation’ (Alex, Citation2019, p. 39). The report which recommended further enquiry into dam management was rejected by the state government (The Hindu, Citation2019). Reluctance to allow scientific scrutiny of the report, perhaps with an eye on impending elections, led to paralysis in decision-making and no action being takenFootnote37 (News Click, Citation2019).

The general narrative in Kerala exposes a lack of transparency in the actual status of dam management in the state. Gadgil observes that the lack of a coherent policy of maintaining water reservoirs came from the profits of calculated mismanagement, as mismanagement assures ‘gains which are spread widely’ (Nidheesh, Citation2018). A major bone of contention between the pro-dam lobby and the environmentalist, and tribal activist groups in Kerala, has been the Athirappilly Hydel Project, which received a no-objection certificate from the state government in 2020.Footnote38 However, environmental concerns and political activism have caused the state government to put the project on hold temporarily (Shaji, Citation2020). Sometimes, political agency can as much effect environmental protection, as it can delay the same.

The issue of dam commissioning has resonances in the whole of India. The continuance of, and even the renewed energy in, commissioning new dams in the most ecologically sensitive areas like Uttarakhand, Arunachal and Chhattisgarh show the synergy of state power and business interests in promoting them with inadequate regard for affected communities and habitats (Aggarwal, Citation2020). However, widespread protests, media attention and scientific criticism have led to some projects being postponed. While such postponement may seem a success of civil society advocacy, communities are still confused by poor information in matters affecting their lives and livelihoods.Footnote39

In 2021, however, the tide in India seemed to be turning with the Dam Safety Act (Central Water Commission, Citation2021). This promoted a proactive approach to flood risk management by its emphasis on dam safety. However, two key stakeholders reported during this research that although the government of Kerala has supported the passing of the Dam Safety Act in the Parliament, it remains to be seen how Kerala will follow through. To date, Kerala is yet to constitute its State Committee on Dam Safety under sub-section (1) of Section 11 of the Act, and State Dam Safety Organization under sub-section (1) of Section 14 of the Act (Central Water Commission, Citation2021). Will this lead to paralysis again?

6.4 A successful example from India

There are individual states, and communities within, that have been known to be proactive in FRM and DRR in India. The example of Odisha where the impact of Cyclone Fani in 2019 was mitigated by robust DRR measures in place is particularly illuminating here. Since the massive losses incurred in the cyclone of 1999, Odisha has put in place a strong Disaster Management Protocol, which has reduced loss of life and property to a bare minimumFootnote40 (Mishra, Citation2013; Patnaik, Citation2019). Odisha maintains its reputation as a role model of proactive DRR to this day, echoed by almost all stakeholders. Effective action was credited to proactive support and initiative from the local, district and state authorities, religious groups, political bodies, and most importantly, participation of local communities. A recent example of the difference community participation and initiative can make is the case of the super-cyclone Amphan in West Bengal in 2020. The communities in the high-risk Sundarbans area, taking care to preserve the embankments built after the experience of Cyclone Aila in 2009, were better able to protect themselves from the disaster (Basu, Citation2020).

7. Conclusion

The analysis of power relations within a bounded rationality framework helps considerably in locating the points at which paralysis occurs in the implementation of proactive FRM and DRR protocols in India. The findings of this research enable the following key understandings:

Power relations amongst stakeholders, and constraints upon them in their contextualised environments direct, determine and can significantly delay decisions on FRM and DRR. The use of the Power-Bounded Rationality framework enables identification and conceptualisation of power relations and pin-pointing of constraints that need to be accounted for in future FRM policy-making and implementation, to address the common paralysis.

Scientific recommendations also come under the pressure of such power relations and constraints. Key recommendations are not just abandoned, but can also be diluted, as the Kerala example highlights.

FRM and DRR need to be contextualised in the larger picture of environmental regulation, conservation, political and commercial lobbying, and local livelihoods. The results of this research highlight how a conservation movement in the Western Ghats has now become integral to discourses there on FRM in Kerala.

And finally, challenges of implementing FRM should not be attributed to the reluctance of ‘people’ to accept restrictions on their ways of life. Recognising the diversity in demographics, geographies, cultures, traditions, politics and practices of India, it thus becomes crucial to better understand power relations, constraints and competing interests of environmental regulation, commercial activities, local livelihoods and political priorities. Competing interests, power exercise and operative constraints will continue, no matter in what form. But conscious attempts to recognise and understand such factors can be a step towards reducing instances of paralysis in flood risk management and disaster risk reduction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28, 40, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50.

2 Stakeholders – 2, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 38, 39, 30, 41, 45, 46.

3 Stakeholders – 5, 6, 7, 11, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 47.

4 Stakeholders – 2, 6, 7, 9, 11, 15, 16, 47.

5 Stakeholders – 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 18, 19, 26.

6 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 39, 46, 48, 50.

7 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 14, 15, 27, 28, 29.

8 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 47.

9 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 45, 46, 47.

10 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 14, 15, 22, 23, 24, 26.

11 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 14, 15, 22, 23, 24, 25, 45, 46.

12 Stakeholder – 25.

13 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 14, 15, 22, 23, 27, 28, 29, 45.

14 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 14, 15, 29.

15 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 14, 15, 17, 47.

16 Stakeholder – 1, 2, 14, 15, 29.

17 Stakeholder – 1, 2, 14.

18 Stakeholder – 1, 2, 14, 15, 27, 29.

19 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 29, 40, 41, 47.

20 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 22, 23, 26, 29, 40, 41, 47.

21 Stakeholders – 4, 5, 8, 9, 13, 14, 16, 46, 47.

22 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 12, 13, 15, 22, 27, 29, 38, 39, 40, 41.

23 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 12, 13, 16, 22, 29, 38, 41.

24 Stakeholders – 1, 4, 5, 7, 22, 34, 36, 37.

25 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 22, 34, 36, 37, 39, 47.

26 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19, 22, 34, 36, 37, 39, 47.

27 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 14, 22, 23, 29.

28 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 27, 29, 47.

29 Stakeholders-1,2,4,5,9,11,12,14,15,16,22,24.

30 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29.

31 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 22, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30, 43.

32 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 34, 36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 44, 47.

33 Stakeholders – 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 47.

34 Stakeholders – 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 13, 17, 22, 23, 24, 29, 38, 39, 40, 41, 47.

35 Stakeholders – 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 17, 22, 23, 24, 27, 29, 40, 41, 47.

36 Stakeholders – 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 13, 17, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 40, 45, 46.

37 Stakeholders – 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 17, 24, 29.

38 Stakeholders – 4, 5, 8, 9, 22, 23, 24, 47.

39 Stakeholders – 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 18, 19, 20, 24, 40, 41, 42.

40 Stakeholders – 45, 46, 48, 49.

References

- Aggarwal, M. (2020). The return of the mega hydropower projects across India. Mongabay, Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://india.mongabay.com/2020/06/the-return-of-the-mega-hydropower-projects-across-india/

- Ailon, G. (2006). What B would otherwise do: A critique of conceptualizations of “power” in organizational theory. Organization, 13(6), 771–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406068504

- Alex, J. P. (2019). Report on Kerala floods, 2018 and management of dams. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.manoramaonline.com/content/dam/mm/mo/news/just-in/pdf/2019/amicus-curiae-report-kerala-flood.pdf

- Allen, J. (2009). Three spaces of power: Territory, networks, plus a topological twist in the tale of domination and authority. Journal of Power, 2(2), 197–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17540290903064267

- Anand, U. (2021, January 4). Govt admits hydropower projects aggravated 2013 Uttarakhand floods. The Indian Express. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/govt-admits-hydro-projects-did-affect-uttarakhand-floods/

- Baan, P. J. A., & Klijn, F. (2004). Flood risk perception and implications for flood risk management in The Netherlands. International Journal of River Basin Management, 2(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2004.9635226

- Babu, P. S. (2019, August 17). Farmers in Kerala struggle to overcome losses after flood havoc. Mathurabhumi. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://english.mathrubhumi.com/agriculture/agri-news/farmers-in-kerala-struggle-to-overcome-losses-after-flood-havoc–1.4046306

- Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. S. (1962). Two faces of power. The American Political Science Review, 56(4), 947–952. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952796

- Baghel, R., & Nusser, M. (2010). Discussing large dams in Asia after the world commision on dams: Is a political ecology approach the way forward? Water Alternatives, 3(2), 231–248. https://www.sai.uni-heidelberg.de/geo/pdfs/Baghel_2010_DiscussingLargeDamsInAsia_WaterAlternatives_3(2)_231-248.pdf

- Bandyopadhyay, J., Mallik, B., Mandal, M., & Parveen, S. (2002). Dams and development: Report on a policy dialogue. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(40), 4108–4112. https://doi.org/10.2307/4415896.

- Banerji, A. (2018a). India wins praise for “exemplary” flood relief as community pitches in. Thomas Reuters Foundation. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://in.reuters.com/article/india-floods/india-wins-praise-for-exemplary-flood-relief-as-community-pitches-in-idINKCN1LC0U3

- Banerji, A. (2018b). Kerala flood: Indians win praise for helping each other through disaster. Global News. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://globalnews.ca/news/4411687/kerala-flood-stories-india/

- Basu, J. (2020, June 9). Cyclone Amphan: How brick homes, Aila embankments saved the day at Sundarbans village. Down To Earth. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/natural-disasters/cyclone-amphan-how-brick-homes-aila-embankments-saved-the-day-at-sundarbans-village-71655

- BBC News. (2020). India landslide: Dozens feared dead after flooding in Kerala. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-53697917

- Begg, Chloe. (2018). Power, responsibility and justice: a review of local stakeholder participation in European flood risk management. Local Environment.

- Beven, K., & Hall, J. (2014). Applied uncertainty analysis for flood risk management. Imperial College Press. https://doi.org/10.1142/P588.

- Bidwai, P. (2013). India floods: A man-made disaster. The Guardian. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/jun/28/india-floods-man-made-disaster

- Birkholz, S., Muro, M., Jeffrey, P., & Smith, H. M. (2014). Rethinking the relationship between flood risk perception and flood management. Science of The Total Environment, 478, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2014.01.061

- Bradford, R. A., O’Sullivan, J. J., Van Der Craats, I. M., Krywkow, J., Rotko, P., Aaltonen, J., Bonaiuto, M., De Dominicis, S., Waylen, K., & Schelfaut, K. (2012). Risk perception – issues for flood management in Europe. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 12(7), 2299–2309. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-12-2299-2012

- Bubeck, P., Kreibich, H., Penning-Rowsell, E. C., Botzen, W. J. W., de Moel, H., & Klijn, F. (2017). Explaining differences in flood management approaches in Europe and in the USA – a comparative analysis. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 10(4), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12151

- Buchecker, M., Ogasa, D. M., & Maidl, E. (2016). How well do the wider public accept integrated flood risk management? An empirical study in two Swiss alpine valleys. Environmental Science & Policy, 55(2), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.021

- Butler, C., & Pidgeon, N. (2011). From ‘flood defence’ to ‘flood risk management’: Exploring governance, responsibility, and blame. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29(3), 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1068/C09181J.

- CABI. (2018). Kerala flooding: Agricultural impacts and environmental degradation. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://blog.cabi.org/2018/09/26/kerala-flooding-agricultural-impacts-and-environmental-degradation/

- Caritas. (2022). Caritas flood relief assistance to Kerala flood 2022. India | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/india/caritas-flood-relief-assistance-kerala-flood-2022

- Central Water Commission. (2018). Kerala floods of August 2018. Government of India.

- Central Water Commission. (2021). Dam Safety Act, Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from http://www.cwc.gov.in/dam-safety-act-2021

- Choudhary, S. (2018, August 21). 400 dead. Crores lost. The cost of the Kerala floods. Mint. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.livemint.com/Politics/AAvubJdXRVDzSxUQogrymO/400-dead-Crores-lost-The-cost-of-the-Kerala-floods.html

- Dahl, R. A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2, 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830020303

- De Brito, M. M., & Evers, M. (2016). Multi-criteria decision-making for flood risk management: A survey of the current state of the art. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 16(4), 1019–1033. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-16-1019-2016

- Disaster Management Division Ministry of Home Affairs. (2018). Disaster Reports, Government of India. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://ndmindia.mha.gov.in/reports

- Down To Earth. (2018, July 2). Kerala submits revised recommendations on Kasturirangan Report. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/forests/kerala-submits-revised-recommendations-on-kasturirangan-report-60961

- Elliot, J. K. (2018). NASA satellite photos show flood devastation in Kerala, India. Global News. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://globalnews.ca/news/4413594/nasa-kerala-flood-india-photo/

- EM-DAT. (2009). Center for research on the epidemiology of disasters. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://emdat.be/

- Emerson, R. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, https://doi.org/10.2307/2089716

- Fischer, L. (2019) At the water’s edge: Motivations for floodplain occupation in flood risk management: Global case studies of governance, policy and communities. E. C. Penning-Rowsell and M. Becker (Eds.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351010009

- Forester, J. (1984). Bounded rationality and the politics of muddling through. Public Administration Review, 44(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.2307/975658

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8(4), 777–795. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343197 https://doi.org/10.1086/448181

- Foucault, M., Faubion, J. D., & Hurley, R. (2020). Power: The essential works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. Penguin, UK. J. D. Faubion (Ed.).

- Gadgil, M. (2014). Expert panel a play in five acts. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(18), 38–50. https://www.epw.in/journal/2014/18/perspectives/western-ghats-ecology-expert-panel.html

- Gadgil, M. (2020). Landslides may have been less intense if Kerala had heeded report. The Wire. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://science.thewire.in/environment/landslides-may-have-been-less-intense-if-kerala-had-heeded-report-madhav-gadgil/

- Ghosh, A., & Kar, S. K. (2018). Application of analytical hierarchy process (AHP) for flood risk assessment: A case study in malda district of West Bengal, India. Natural Hazards, 94(1), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3392-y

- Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Polity Press.

- Gigerenzer, G., & Selten, R. (2002). Bounded rationality: The adaptive toolbox. MIT Press.

- Government of India. (2005). The disaster management act, 2005. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.ndmindia.nic.in/images/The Disaster Management Act, 2005.pdf

- Government of India. (2009). National policy on disaster management. National Disaster Management Authority. https://ndma.gov.in/sites/default/files/PDF/national—dm—policy2009.pdf

- Government of India. (2019). National disaster management plan. National disaster management authority. https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/National Disaster Management Plan May 2016.pdf

- Hall, J., & Solomatine, D. (2008). A framework for uncertainty analysis in flood risk management decisions. International Journal of River Basin Management, 6(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2008.9635339

- Hall, J. W., Meadowcroft, I. C., Sayers, P. B., & Bramley, M. E. (2003). Integrated flood risk management in England and Wales. Natural Hazards Review, 4(3), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2003)4:3(126)

- Hindustan Times. (2018). Alarmed by Kerala floods, NGT bars further reduction in Western Ghats ESAs. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/alarmed-by-kerala-floods-ngt-bars-further-reduction-in-western-ghats-esas/story-AxZRreKB3ymiNmtPo2HGbJ.html

- Indian Express. (2022). Kerala rains updates: Red alert in 8 districts, thousands evacuated as rivers swell. Indian Express. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://indianexpress.com/article/india/kerala/kerala-rains-live-updates-red-alert-flooding-traffic-8067117/

- Indian Meteorological Department. (2020). Customized Rainfall Information System (CRIS). Retrieved December 9, 2020, from http://hydro.imd.gov.in/hydrometweb/(S(djpklq45nttxrkm1xxfkmbrs))/landing.aspx

- India Today. (2013, June 20). Environmentalists blame it on Centre, state government for man-made disaster in Uttarakhand. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/north/story/uttarakhand-floods-environmentalists-blame-it-on-centre-state-govt-for-man-made-disaster-167419-2013-06-20

- India Today. (2019, August 19). Death toll in flood-hit Kerala rises to 121, 40 injured. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/death-toll-in-flood-hit-kerala-rises-to-121-40-injured-1582258-2019-08-19

- Ingold, K., & Gavilano, A. (2019). Under what conditions does an extreme event deploy its focal power? : Toward collaborative governance in Swiss flood risk management. 1st ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429244308-11.

- Islam, A., & Ghosh, S. (2022). Community-based riverine flood risk assessment and evaluating its drivers: Evidence from Rarh plains of India. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 15(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-021-09384-5

- Jacob, J. (2022). Why Kerala fears another monsoon of miseries. India Today. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/why-kerala-fears-another-monsoon-of-miseries-1956545-2022-05-31

- Joseph, S. T. (2019). Recurring Kerala flood- a need for re-thinking Gadgil report. Journal of Composition Theory, 12(11). 19.18001.AJCT.2019.V12I11.19.10810

- Kanth, A. (2019). Kerala floods: Tribal farmers in Wayanad the worst-affected. The New Indian Express. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2019/aug/15/kerala-floods-tribal-farmers-in-wayanad-the-worst-affected-2019094.html

- Karun, S. (2019, May 16). Kerala: Agriculture flood damage touches Rs 6,281 crore. The Times of India. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/kerala-agriculture-flood-damage-touches-rs-6281-crore/articleshow/69352122.cms

- Kasturirangan, K., Babu, C. R., Chopra, K., Shankar, D., Roy, P. S., Chandrasekharan, I., Mauskar, J. M., Kishwan, J., Narain, S., & Tyagi, A. (2013). Report of the high level working group on Western Ghats, Ministry of Environment and Forests’.

- Kates, R. W. (1962). Hazard and choice perception in flood plain management (Doctoral dissertation. The University of Chicago.

- Kellens, W., Terpstra, T., & De Maeyer, P. (2013). Perception and communication of flood risks: A systematic review of empirical research. Risk Analysis, 33(1), 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01844.x

- Kerala State Disaster Management Authority. (2016). Kerala state disaster management plan towards a safer state. Kerala State Disaster Management Authority. https://sdma.kerala.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Kerala%20State%20Disaster%20Management%20Plan%202016.pdf

- Kerala State Disaster Management Authority (2022). Members of DDMA, Kerala state disaster management authority. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://sdma.kerala.gov.in/members-of-ddma/

- Khambete, A. K. (2019). From droughts to floods: India’s tryst with climate extremes. India Water Portal. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.indiawaterportal.org/articles/droughts-floods-indias-tryst-climate-extremes

- Khanduri, K., Singh, A., Garg, P., & Singh, D. (2013). Uttarakhand Himalayas: Hydropower developments and it’ s impact on environmental systems. Journal of Environment, 2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264673061_Uttarakhand_Himalayas_Hydropower_Developments_and_its_Impact_on_Environmental_System

- Kukreti, I. (2020, August 13). Draft EIA: SC rejects centre challenge to Delhi HC translation order. Down To Earth. Retrieved January 4, 2021, from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/environment/draft-eia-sc-rejects-centre-challenge-to-delhi-hc-translation-order-72803

- Kumar, G. K. (2018). Land-use planning is key to preventing disasters. The Hindu. Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/land-use-planning-is-key-to-preventing-disasters/article24822592.ece