Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this paper is to describe non-participation during the outcome measurement step of the wheeled mobility service delivery process (WMSDP) based on the Functional Mobility Assessment (FMA)-Uniform Dataset (UDS) Registry.

Introduction

The WMSDP is a standard framework for the provision of wheeled mobility devices, and several factors influence the client’s experience throughout the process. Patient-reported outcomes are one way to measure the client’s experience as part of a quality improvement program.

Methods

A retrospective descriptive study was conducted on the FMA-UDS Registry to measure the response rate during the outcome measurement step of the WMSDP and describe the reasons an individual did not complete the FMA-UDS. The FMA-UDS was examined at two time points: pre-delivery and post-delivery of the wheeled mobility device.

Results

As of September 2, 2021, 10,253 cases have been entered into the FMA-UDS Registry. 2,247 cases were no longer participating pre-delivery, and an additional 3,905 cases were no longer participating post-delivery. The most common reasons for non-participation in the FMA-UDS pre-delivery and post-delivery included: equipment not delivered; provider no longer participating in the FMA-UDS; funding issues; no new equipment; client opted out; loss in contact; deceased; returned equipment; and other.

Discussion

The type and frequency of non-participation in the outcome measurement step of the WMSDP is critical to understanding why individuals participate in outcome measures and provides insight into the barriers and facilitators for the implementation of quality improvement programs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

The outcome measurement system provides a structured mechanism for consistent communication between the client and the professionals providing the service, thereby identifying issues earlier in the process and mitigating frustration throughout the wheeled mobility service delivery process.

The role of a credentialed professional, specifically an Assistive Technology Professional, in the wheeled mobility service delivery process could emphasize the importance of the follow-up and outcome measurement steps, which may increase the consumers’ participation rate and demonstrate the effectiveness of devices and services.

Clients who no longer participate in the outcome measurement process do not have the sustained support of the interprofessional team, and possess an increased chance that they will not get their mobility needs met through the health care system.

Introduction

Mobility is a key component to everyday life because it promotes independence, social participation, health, and quality of life. Conversely, limitations in mobility can lead to negative outcomes, which may include an inability to perform activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, or participate in health, employment and education [Citation1]. Wheeled mobility is one common assistive technology device to aid individuals with limited mobility. The assistive technology service delivery process, in general, and the wheeled mobility service delivery process, in particular play a critical role in the identification, recommendation, implementation and sustained use of wheeled mobility by individuals with limited mobility. Given the opportunity to use assistive technology, an individual’s perceived benefit with assistive technology plays an integral role in whether they will use the technology long term [Citation2]. One mechanism for determining the perceived benefit is through the administration of client-reported outcome measures during the service delivery process. However, if an individual does not participate in an outcome measurement process, then assistive technology service delivery programs do not have the opportunity to measure the perceived benefit of both the device and the service. Given the role of wheeled mobility in the lives of individuals with mobility limitations, it is important to identify and describe the reasons that individuals do not participate in the outcome measurement process within an assistive technology service delivery program.

Wheeled mobility service delivery

The wheeled mobility service delivery process is a framework that describes the process by which individuals with mobility impairments select wheeled mobility devices in collaboration with an interprofessional team. The assistive technology service delivery process, as described by Cook et al. [Citation3,p.87-116], is a closed loop system that includes seven steps ranging from referral and intake to evaluating the effectiveness of the technology [Citation3,p.87-116]. The wheeled mobility service delivery process is a specialized case of the AT service delivery process and includes many of the same steps. According to the RESNA Wheelchair Service Provision Guide, the wheeled mobility service delivery process includes the following components: 1) Referral; 2) Assessment; 3) Equipment Recommendation and Selection; 4) Funding and Procurement; 5) Product Preparation; 6) Fitting, Training and Delivery; 7) Follow- up, Maintenance and Repair; and 8) Outcome Measurement [Citation4]. Similarly, Eggers et al. identified seven steps in the wheelchair service delivery process that are similar to both the AT service delivery process and the RESNA wheelchair service provision guide [Citation5]. The continued use of technology is based on a closed loop feedback system where individuals continually evaluate the perceived relative advantage of technology over parallel interventions [Citation2]. Given the multiple steps of the wheeled mobility service delivery process, the closed-loop nature of the service delivery process, and the variables that impact an individual’s use or non-use of the technology, there are several reasons an individual may not complete the wheeled mobility service delivery process, as measured through the outcome measurement step.

Patient-Reported outcome measures

One of the accepted outcome measures for addressing quality improvement is patient centeredness or patient experience, which are often measured through patient-reported outcomes. Patient-reported outcome measures are defined by the Food and Drug Administration as any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else [Citation6]. In order to evaluate an intervention, patients are able to report on domains such as symptom experiences, functional status, wellbeing, quality of life, and satisfaction with care or with a treatment [Citation7–9]. Therefore, patient-reported domains can be used to address quality improvement.

One way to measure patient-reported outcomes for the service delivery of a wheeled mobility device is through the FMA-UDS. The FMA is a patient-reported outcome measure questionnaire that assesses satisfaction in performing mobility-related activities of daily living [Citation10]. The UDS is a core system of information appropriate for reviewing the operation and performance of health centers. The data are used to identify trends over time in order to improve performance and operation. The final UDS developed by Schmeler [Citation10] included information on demographics, equipment, health and safety, activity, and participation in order to gather information about the person, the mobility device, and the person’s living situation. Based on the FMA-UDS Registry, which is completed at several time intervals during the service delivery process, the purpose of this paper is to describe the type and frequency of common reasons an individual did not participate in the FMA-UDS associated with the outcome measurement step of the wheelchair service delivery process.

Methods

Population and sample

Adults with mobility impairments participated in the FMA-UDS as part of the assessment, fitting, and follow-up components of the wheelchair service delivery process. The wheelchair service delivery process was completed by a transdisciplinary team including the client, equipment providers, and clinicians. The data for this study were retrieved from the FMA-UDS Registry. Data from the FMA-UDS Registry is collected through an exempt IRB at the University of Pittsburgh and by a Collaborative Corporate Research Agreement with the Van G. Miller Group, Inc. (VGM). U.S. Rehab is a division of the VGM that works with nearly 400 independent complex rehabilitation dealers and has nearly 1400 provider locations within the U.S. In addition, U.S. Rehab is contracted by health care facilities within the United States to administer the FMA-UDS as part of the facilities’ quality improvement programs. All data sent to investigators was de-identified and investigators have no ability to trace data back to any protected health information.

Design

A retrospective descriptive analysis was conducted on the entire FMA-UDS Registry. The FMA-UDS consists of two distinct sections: the FMA, which addresses the individual’s perceived satisfaction with their functional mobility, and the UDS which addresses the individual’s background information [Citation10]. The FMA includes ten statements that address an individual’s satisfaction with their ability to move around the community. For example, the FMA statements address an individual’s ability to carry out their daily routine, perform tasks at different surface heights, transfer form one surface to another, and get around outdoors. The UDS includes information about the individual (e.g., height, weight, diagnosis), the individual’s current mobility equipment, their mobility experiences in the home and community (e.g., frequency of falls and leaving the home), their experiences with mobility equipment (e.g., duration of use), their overall experiences in the community (e.g., transportation, employment), and their participation with the service delivery process.

For the purposes of this retrospective descriptive analysis, we focused on the individual’s participation with the service delivery process as measured by a single question on the UDS: “What is the client’s current status in terms of participation in the FMA-UDS Registry?”. Therefore, the question addressing the client’s current status was reviewed to determine common responses detailing an individual’s reason for no longer participating in the FMA-UDS Registry. The reasons for no longer participating in the Registry are described in . The individual’s status in the FMA-UDS Registry describes an individual’s rationale for participation in the outcome measures step of the wheelchair service delivery process.

Table 1. Reasons for non-participation in the FMA-UDS Registry, and the operational definition for each item.

Procedures

At the time of a new mobility intervention, equipment providers and/or clinicians administered the FMA-UDS to people with disabilities. An internal representative, who was trained on the administration of the FMA-UDS, completed follow-up surveys with the client via a telephone call or written communication. The FMA and UDS were repeated at 21 days post-delivery of new equipment, 90 days, 180 days, 365 days, and annually thereafter. If the telephone follow-ups were unsuccessful after three attempts, which were staggered in terms of call time (i.e., morning, lunchtime, and late afternoon), the survey was mailed to the individual. Participating equipment providers and health care facilitates pay a nominal fee to participate in the Registry.

Data collection and analysis

Each individual’s descriptions from the not-active for ‘Status of Current Client’ question were recorded within the HomeLink database. The HomeLink database is a secure database housed within the VGM headquarters. Through an exempt institutional review board and vetted data sharing agreement, U.S. Rehab sends batches of de-identified data to University of Pittsburgh investigators for review & analysis. The ‘Status of Current Client’ question was summarized based on the frequency of responses across multiple timepoints. Specifically, the number of individuals who were participating in the outcome measures step of the wheelchair service delivery process was measured. For the individuals who were no longer participating in the outcome measures step, the reason (e.g., loss contact, client opted out) and timing (e.g., assessment, fitting, or follow-up) for their non-participation was summarized.

Results

As of September 2, 2021, 10,253 cases have been entered into the FMA-UDS Registry. According to data from the FMA-UDS Registry, 2,247 were listed as not active before the fitting, training, and delivery step of the wheeled mobility service delivery process (Time 1). The reason for non-participation in the outcome measurement process prior to delivery of the wheeled mobility device, along with the frequency and rate for each reason, are provided in . The reasons for inactivity described by the “other” category included the following descriptions: included wrong form; hospice; skilled nursing facility; environmental/accessibility issue; client moved out of state/country; client switched providers; client needed re-evaluated; client worked directly with vendor or Department of Veterans Affairs; and client already had equipment. A reason for non-participation was in the “other” category if it had it occurred at a rate of less than 1%.

Table 2. Reasons for inactivity before and after delivery of wheeled mobility device.

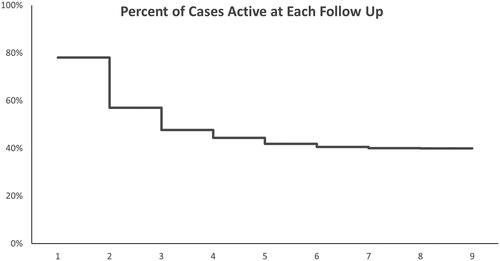

After the fitting, training and delivery step of the wheeled mobility service delivery process, the number of cases listed as “Not Active” decreased over time (). At the first follow up (Time 2), 2157 cases were inactive, while at the eighth follow up (Time 9), only 1 case was inactive. Similar to the Time 1 results, a reason for inactivity was identified during each follow-up survey (). The reasons for inactivity described by the “other” category included the following descriptions: wrong form; hospice; skilled nursing facility; environmental/accessibility issues; client moved out of state/country; client switched provider; client returned and received a different device in return; Time 1 completed after delivery date; and delivery over one year past evaluation. As with the Time 1 data, a reason for non-participation was in the “other” category if it had it occurred at a rate of less than 1%.

Table 3. Reasons for inactivity after delivery of wheeled mobility device.

Demographic data was collected for all cases entered into the FMA-UDS. As of July 7, 2021, 7,733 cases had been entered into the FMA-UDS Registry. Out of these 7,733 cases, 52.67% were female and 47.03% were male. Primary diagnoses reported for these cases were other neuromuscular or congenital disease (22.63%), stroke (10.59%), osteoarthritis (10.13%), cerebral palsy (8.53%), paraplegia (7.23%), amputation (5.99%), multiple sclerosis (5.51%), cardiopulmonary disease (4.29%), tetraplegia/quadriplegia (3.14%), and Parkinson disease (2.48%). The most common funding source used by these cases was Medicare (33.76%) followed by Medicare Managed Care (16.02%), Medicaid (14.11%), private insurance-HMO (11.29%), Medicaid Managed Care (8.08%), private insurance-fee for service (6.44%), and other/not listed (6.38%). Other funding sources such as missing, VA, private pay, vocational rehab, and worker’s compensation were mentioned but make up less than 4% of the total funding sources. The sex, diagnosis and funding source provide an overview of the individuals participating in the outcome measurement process. We were not able to match the demographic data specifically with the 6,152 cases that were “Not Active” due to the limitations of using a registry with de-identified data.

Discussion

The type and frequency of non-participation in the outcome measurement step of the wheelchair service delivery process is critical to understanding why individuals participate in outcome measures and provides insight into the barriers and facilitators for the implementation of quality improvement programs when using a patient-reported outcome measure, specifically the FMA-UDS. A retrospective analysis of 10,253 cases from the FMA-UDS Registry were reviewed, and over the course of up to 5 years (Time 9), 6,152 individuals were no longer participating in the outcome measurement process. Therefore, within the auspices of a quality improvement program, we reviewed the reasons individuals were no longer participating to identify potential changes to the wheelchair service delivery process, in general, or the outcome measurement process, in particular.

Most common reasons for non-participation

Numerous implementation outcomes describe potential barriers and facilitators to the outcome measurement process based on an individual’s participation in the outcome measurement process. The barriers and facilitators range from acceptability and adoption to feasibility and sustainability, and are influenced by the consumer, provider, and organization [Citation11]. For our purposes, the organization includes the wheelchair provider, manufacturer, and third-party payer. At Time 1, prior to delivery of a new mobility device, the most common reason for non-participation was that the device was not delivered. The device may not have been delivered for distinct reasons such as it had been over 180 days since T1 with no delivery or unknown reasons, which could be related to the consumer, provider, or organization. For example, there may be challenges acquiring funding, delays in completing documentation, challenges with acquiring equipment, or the consumer no longer needs the equipment. The second most common reason for non-participation before device delivery was that their provider was no longer participating in the FMA-UDS Registry. Addressing non-participation at Time 1 is critical due to the high rate of non-participation, which can impact the organization’s ability to provide effective wheelchair devices and services.

In contrast to Time 1, at Time 2 and Time 3, the first two follow-up surveys, the most common reason for non-participation was loss in contact. For example, this may be due to a change in the consumer’s primary address or phone number. However, similar to Time 1, the second most common reason for non-participation was that their provider was no longer participating in the FMA-UDS Registry. For example, a provider could have started the FMA-UDS but then during the service delivery process, the provider company was acquired by a non-member company that is not participating in the FMA-UDS registry. If the provider is no longer participating in the FMA-UDS, then the client will no longer receive a follow-up survey from a VGM representative. The reasons for non-participation in the outcome measurement step of the wheelchair service delivery process are consistent with implementation barriers described in the literature and addressed at professional conferences in the field of seating and mobility.

The most common reasons for non-participation prior to delivery and at the first two follow-ups are not surprising. First, a client may not need a new device, or may not have funding for the device. Second, a provider may decide early on that the FMA-UDS is not acceptable or appropriate given their business and service delivery model. Third, a significant amount of effort is required to develop buy-in among the various stakeholders, particularly the wheelchair provider staff, wheelchair provider administration, clinician, or client, therefore, without appropriate training and motivation, the stakeholders may not find value in the outcome measurement step. Finally, logistical barriers may interfere with participation in the FMA-UDS survey and limit the feasibility for early adoption. For example, a client may not have time to complete the follow-up questionnaire or may be unfamiliar with the phone number and message from the VGM representative when they are contacted for follow-up and, therefore, not answer phone calls from the VGM representative. The acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the outcome measurement process are key to the early-stage adoption of a new service delivery process, in this case the FMA-UDS Registry.

During the remaining time intervals, the most common reasons for non-participation was loss in contact, client opted out, and deceased, which align with acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility implementation outcomes [Citation11]. The loss in contact and client opted out may be a result of logistical barriers that affect the feasibility of the program, and the buy-in of the wheelchair provider or clinician which impact the acceptability and appropriateness of the program. Opting out could potentially be a result of the wheelchair provider or clinician not emphasizing to the client the importance of outcome measurement process or the client not having time to complete the questionnaire across multiple time intervals. Because there is slight variation in the most common reasons for non-participation during follow-up time intervals, it is unknown if time plays a role in satisfaction with the wheelchair service delivery process or if other factors are infringing upon receiving regular follow-up surveys from the client. Overall, the primary reasons for non-participation are the device was not delivered, the provider is no longer participating in the FMA, loss in contact, client opted out and deceased. This information can be used to improve the collection of outcome measures, and therefore the quality of the wheelchair service delivery process.

Influences on non-participation

Several factors could influence why an individual would participate in the outcome measurement step of the wheelchair service delivery process. Using the HAAT model as a foundation, the factors could include the characteristics of the consumer and the context in which the individual acquires and uses the device [Citation3]. As noted previously, Proctor [Citation11] describes three levels of analysis when describing the implementation outcomes: consumer, provider, and organization. At the level of the consumer, demographic data such as sex, diagnosis, and funding source could play a role in participation in the outcome measurement step of the wheelchair service delivery process. If funding is a barrier for an individual, they may not receive their equipment and, therefore, would not continue in the complete FMA-UDS survey. Additionally, if their medical condition changes as a result of their diagnosis, they may not be in a position to complete follow-up questionnaires.

The fidelity with which the provider organizations implement the wheeled mobility service delivery process, and the professionals involved in the wheeled mobility service delivery process could influence participation at the consumer, provider, and organization levels. Based on anecdotal observations at industry continuing education events and conferences, and the authors’ combined 70+ years of experience in the field, many provider organizations do not complete all steps of the wheeled mobility service delivery process. Each step of the service delivery process provides an opportunity for the staff within the provider organization to discuss the importance of outcome measures. For example, wheelchair skills training is an important part of the assessment, training and follow-up steps of the service delivery process, however many provider organizations focus on the device set-up and maintenance, rather than wheelchair skills at the time of delivery and during follow-up sessions. Increased focus on completing all steps in the wheeled mobility service delivery process may increase participation in the outcome measures step, which may increase a client’s satisfaction with their device and the service delivery process.

At the level of the provider, the involvement of a credentialed professional in the service delivery process, for example a licensed clinician or RESNA-certified Assistive Technology Professional (ATP), could influence participation at the consumer, provider, and organization levels. For example, ATPs follow RESNA’s Standards of Practice which states that ATPs must “institute procedures, on an on-going basis, to evaluate, promote and enhance the quality of service delivered to consumers [Citation12]. The importance of the ATP in wheelchair service delivery has been demonstrated through prior research that suggests improved outcomes when an ATP is involved in the service delivery process [Citation13]. Therefore, the role of a credentialed professional, specifically an ATP, could emphasize the importance of the follow-up and outcome measurement steps in the service delivery process, which may increase the consumers’ participation rate and demonstrate the effectiveness of devices and services.

Service delivery implications

The assistive technology centers that the authors represent have significant experience implementing the FMA-UDS. Based on their anecdotal experience with the FMA-UDS, several themes have emerged that provide insight into the implications of non-participation. Clients who no longer participate in the outcome measurement process possess an increased chance that they will not get their mobility needs met through the health care system. This can cause catastrophic equipment failures, which may lead to pressure injury development or a complete lack of mobility at home and in the community. Clients at the assistive technology centers often have chronic disability and have to manage multiple appointments while navigating difficult systems. We have found that many clients don’t know who to call, and when to call them as a result of the complex system. The outcome measurement system provides a safety-net for communication with client’s thereby improving their overall experience. Finally, we have found that a growing number of clients are becoming frustrated with the service delivery process and take much of that frustration out on the front-line personnel, namely clinicians, ATPs and technicians. The outcome measurement system provides a structured mechanism for consistent communication with the client, thereby identifying issues earlier in the process. The early identification of issues may mitigate the frustration, which leads to a better experience for the client and the professionals providing the services. Decreasing the rate of non- participation in the outcome measurement process is critical to supporting individuals with disabilities through the complex process of acquiring and maintaining a wheeled mobility device.

Limitations

There are several limitations to note for this study. Primarily, it is important to note that the FMA-UDS Registry is a self-reporting system. This causes data to be subjective in nature since everyone perceives and categorizes experiences differently. Secondly, the FMA does not provide a list of operational definitions for terms used on the assessment. This could cause different interpretations of items on the assessment among different providers and different clients, which could impact responses. Lastly, demographic data used in this study cannot be matched exactly to specific individuals who stopped participation in the outcome measurement step due to the de-identified nature of the data. This leads to using a sub-sample of the entire population to describe the demographic make-up of the population include in the analysis of non-participation rates.

Future research

The de-identified nature of the data and inability to match demographic data to specific individuals indicates that there is a gap in knowledge on the influence of demographic data such as sex, funding, device prescribed, and diagnosis on non-participation in the outcome measurement step during the wheeled mobility service delivery process. In quarterly data reports provided to U.S. Rehab, it is indicated that FMA scores tend to increase as follow-up increases. Similarly, there could be a correlation present between demographic information and non-participation in the wheeled mobility service delivery process, which would negatively impact FMA scores. If providers are made aware of these types of correlations, they could adjust their intervention accordingly to ensure a more successful service delivery experience for the client.

Conclusion

Implementation of a quality improvement program is a long-term process, but it is important in improving clinical outcomes. One important method to improve clinical outcomes is recording patient-reported follow-up data to detect differences between interventions or to evaluate if changes in interventions are effective. Although the FMA is a useful tool for wheelchair providers and clinics to track improvements in interventions, it is also provides a mechanism to track clients who are not participating in the wheeled mobility service delivery process, which is just as important. By determining reasons for individuals being listed as “Not Active” wheelchair providers and clinics are able to adjust their approach to reaching clients for follow-up or emphasizing the importance of follow-up for long term success from the initial appointment. Although there are limitations administering follow-ups via telephone, the benefits outweigh the barriers. Future research is needed to evaluate if any factors, such as sex, funding source, or diagnosis provide a correlation to non-participation in the outcome measurement step of the wheeled mobility service delivery process, which may be a proxy for participation in the overall wheelchair service delivery process.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize Mark R. Schmeler, PhD, OTR/L, ATP from the University of Pittsburgh and Tricia Dowd from U.S. Rehab for their contributions to this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Occupational Therapy Organization. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process—fourth edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(Suppl_2):7412410010.

- Lenker JA, Paquet VL. A new conceptual model for assistive technology outcomes research and practice. Assist Technol. 2004;16(1):1–10.

- Cook AM, Polgar JM, Encarnação P. Principles of assistive technology. In: Assistive technologies. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier; 2020.

- Arledge S, Armstrong W, Babinec M, et al. RESNA Wheelchair Service Provision Guide. Approved by RESNA BOD. 2011 https://www.resna.org/Portals/0/Documents/Position%20Papers/RESNAWheelchairServiceProvisionGuide.pdf

- Eggers SL, Myaskovsky L, Burkitt KH, et al. A preliminary model of wheelchair service delivery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(6):1030–1038.

- Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ’Quality chasm’ report. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(3):80–90.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download

- Scientific advisory committee of the medical outcomes trust. Assessing health status and quality of life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):193–105.

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–745.

- Schmeler MR, Schein RM, Saptono A, et al. Development and implementation of a wheelchair outcomes registry. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(9):1779–1781.

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

- RESNA. Standards of practice. Arlington (VA): Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America; 2008. https://www.resna.org/Certification/Ethics-and-Standards-of-Practice/Standards-of-practice

- Schein RM, Yang A, McKernan GP, et al. Effect of the assistive technology professional on the provision of mobility assistive equipment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(10):1895–1901.