Abstract

Purpose

People with disability often require long-term care. Long-term care is changing with the availability and advances in cost and function of technologies, such as home automation. Home automation has the potential to reduce paid carer hours and can potentially offer many benefits to people with a disability. The aim of this scoping review is to identify the health, social and economic outcomes experienced by people living with a disability who use home automation.

Materials and methods

Two electronic databases were searched by title and abstract to identify international literature that describes home automation experiences from the perspectives of people with disability. A thematic approach was taken to synthesise the data to identify the key outcomes from home automation.

Results

The review identified 11 studies reporting home automation outcomes for people living with a disability. Seven outcomes were associated with home automation: independence, autonomy, participation in daily activities, social and community connectedness, safety, mental health, and paid care and informal care.

Conclusion

Advances in technology and changes in funding to support people living with a disability have made access to home automation more readily available. Overall, the study findings showed that there is a range of potential benefits of home automation experienced by individuals living with a disability.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

A wide range of outcomes have been evaluated following the installation of home automation systems for people with disability.

Key outcomes evaluated to date include independence, autonomy, participation, safety, mental health, and reduced need for paid carers.

Outcomes of home automation appear to be connected; for example, improved participation may lead to improved mental health.

Introduction

In Australia, 1 in 6 people (4.4 million) are living with a disability, and 5.7% of the Australian population report living with a severe disability [Citation1]. Physical disability is the most common type of disability. World-wide, one billion people are living with a disability and the number is increasing in all countries due to the ageing population and the increase in chronic diseases [Citation2]. In 2018, nearly 3.9 million Australians experienced some form of limitation in their core activities such as communication, mobility, employment, education, or self-care [Citation1]. Three-fifths of people with disability require assistance with daily activities, and just over half require aids or equipment for support [Citation1]. Currently 40% of people living with a disability in Australia require formal care [Citation3].

Home automation refers to the installation of technology that automates or remotely controls household functions via technological devices and programs linked via a wired or wireless connection [Citation4–6]. Home automation can control doors, blinds, heating and cooling, lighting, windows, doorbells and intercom systems, taps, showers, and entertainment systems via smartphones or tablets, and/or voice control operated systems. Some home automation is intended to increase independence and enhance the quality of life of a person living with a physical, sensory, or intellectual disability. The costs of home automation vary, and while cost-effectiveness has not been assessed to date, it is possible that the installation of home automation is a way of reducing reliance on paid carers [Citation7].

Funding for home automation is available in some developed countries such as the UK and USA through registered disability charities and programs for assistive technology [Citation8,Citation9]. In Australia, the majority of funding for home automation for adults aged over 65 years old is provided by the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA). It is estimated that only 5% of NDIA funding is spent on assistive technology, however, a review of the social and economic impacts of assistive technology more broadly found that assistive technology has the potential to reduce costs in health and aged care [Citation10]. Funding for home automation for people living with a disability is relatively new and evaluation of the social and economic impact has been limited to date. Indeed, many current and early adopters of home automation are self-funded [Citation7].

This scoping review identified the outcomes of home automation by people living with a disability (cognitive and physical). This was achieved by (1) searching published literature for studies relating to outcomes of home automation for people living with a disability and (2) synthesising the outcomes experienced of home automation for people living with a disability into themes. As far as we are aware, no current scoping review has been undertaken identifying the outcomes of home automation for people living with a disability.

Material and methods

The scoping review followed the PRISMA guidelines with the extension for scoping reviews [Citation11] to identify the literature describing outcomes of home automation for people with a disability. Unlike a systematic review that critically appraises literature, a scoping review aims to provide an overview of literature on a given topic and does not involve a critical appraisal of the literature [Citation12]. A scoping review was chosen to identify the body of literature relating to the research aim and provide an overview of what evidence is available [Citation12,Citation13].

Identification and selection of studies

Search strategy

Two databases (SCOPUS and IEEE Xplore digital library) were searched (July 2022) by title and abstract using the following search terms: (“home automation” OR “environmental control system” OR “environmental control unit” OR “smart home” OR “smart house” OR “smart device” OR “home technology”) AND (“disab*” OR “injur*” OR “*plegia” OR “impair*” OR “disorder” OR “difficult*”). These databases were chosen as the most likely to provide literature from the fields of health and information and communication technologies. Scopus was included as it is one of the largest electronic databases which covers the health, social and physical sciences. Scopus includes a range of publication types including book chapters and covers the majority of titles included in Medline. IEEE Xplore was included as it provides comprehensive coverage of literature from engineering, computer science and electronics publications.

Eligibility criteria

The review searched for articles published from 2011 onwards as home automation has become more readily available in the last decade following technological advances [Citation7,Citation14]. Eligible studies included adults with any type of physical and/or cognitive disability using home automation. For this review, home automation was defined as any form of technology that automates or remotely controls household functions [Citation5,Citation6]. The review did not exclude any study based on their design, which allowed case studies, quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies to be included. Included studies had to have identified at least one outcome of home automation experienced by a person with the disability. Studies were excluded if they were theses, reviews, book reviews, editorials, opinion pieces, conference abstracts or were not published in English. Outcomes of interest were health, social and economic outcomes.

Procedure

Citations were extracted from the electronic databases into Covidence, a web-based software platform [Citation15] and duplicates removed. The first stage of screening involved two reviewers independently screening the articles by title and abstract. Any articles that appeared irrelevant were excluded at this point. The second stage of screening involved three reviewers screening the full-texts of the articles which were potentially relevant with any conflicts being resolved via a discussion between the reviewers.

Data analysis

A thematic approach was taken to synthesise the data to identify the key outcomes of home automation. Firstly, the two reviewers read the articles to become familiar with the content. Secondly, data extraction (author, year of publication, country, aim, study population and sample size, setting, methods and key findings, as recommended by Tricco et al. [Citation11]) for the first 20% of articles was completed by two reviewers and then both reviewers met to discuss the extracted data. The remainder of the extraction was completed by one reviewer and checked by the second reviewer. Finally, the two reviewers met to identify the outcomes emerging from the sources and to group the outcomes into themes.

Results

Flow of studies through the review

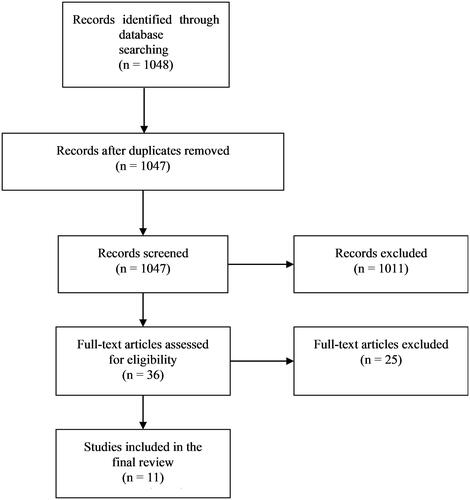

A total of 1048 articles were imported into Covidence. After removing one duplicate, 1047 articles were screened by title and abstract with 1011 articles excluded. Thirty-six full text articles were assessed for eligibility, with 25 articles excluded. The most common reasons for exclusion were not identifying outcomes (n = 9), wrong population (n = 5) and wrong intervention (n = 5). A total of 11 studies were included in the scoping review. The results of this process are shown in . provides further details of the final studies included in the review.

Figure 1. Flow chart of study identification process.

Table 1. Study details.

Characteristics of studies

All articles reviewed were published between 2013 and 2022. Four studies were conducted in Australia, two in Ireland, one in France, one in Italy, one in Slovenia, one in England, and one in the USA. Six studies presented quantitative data on the outcomes of using home automation [Citation16–21] with two of these studies involving a non-randomised control group [Citation17,Citation18]. One study presented quantitative and qualitative data [Citation7], and the remaining four presented qualitative data [Citation22–25]. Study quality was not appraised.

Participants

Overall, studies were relatively small and sample sizes of studies ranged from one participant (case study) to fifty-nine participants. The age of participants ranged from 18 years to 86 years, with over half of the participants in all studies being males (56%). Six of the eleven studies included individuals with spinal cord injuries. Other studies included individuals with moderate to severe functional limitations (n = 1), neurotrauma (n = 1), down syndrome (n = 1), motor neurone disease (n = 1) and individuals who had experienced a stroke (n = 1).

Type of home automation

Studies included a range of different home automation technologies. The most common type of home automation used by participants was technology to control televisions (n = 7 studies), lights (n = 7 studies), air conditioning/heating units (n = 7 studies) and doors (n = 5 studies). Opening windows, voice-controlled emails and kitchen appliances were the least common type of home automation identified (n = 1 study).

Outcomes

The analysis of the studies identified seven outcomes. provides detail of the outcomes of home automation experienced by individuals living with a disability for each study.

Table 2. Outcomes of each study.

Performance of daily activities

Daily activities refer to the ability of an individual to perform everyday activities such as meal preparation or showering. Ten studies reported the association between home automation and individual engagement in daily activities [Citation7,Citation16–22,Citation24,Citation25]. Of the ten studies that reported outcomes related to daily activities, seven used quantitative standardised tools. These included the Assessment of Quality of Life measure (AQoL-4D) [Citation26]; the Residential environment impact survey – short form (REIS-SF) [Citation27]; Association for the Retarded Citizens self-determination scale (ARC) [Citation28]; Psychological Well-being Scales (PWS) [Citation29,Citation30]; Activities of Daily Living (ADL), [Citation31]; Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL), [Citation32]; Functional Independence Measure (FIM) [Citation33]; The Barthel Index (BI) [Citation34] and the Frenchay Activities Index (FAI) [Citation35]. Study participants included those with Down’s syndrome, spinal cord injury, motor neurone disease, and stroke with findings indicating an increase in ability to perform daily activities [Citation7,Citation16–21]. Two of these studies compared individuals accessing home automation to a control group (no access to home automation) and both studies reported an increase in ability to manage daily activities in the intervention group compared to the control group [Citation17,Citation18]. Three further studies which adopted a qualitative approach with individuals with spinal cord injuries described how home automation could increase people’s ability to manage daily activities [Citation22,Citation24,Citation25].

Paid care and informal care

Paid care is performed by care workers who receive renumeration for their work caring for individuals. Informal care is provided by people who have an existing relationship with the individual such as a family member, a friend or neighbour [Citation36]. The impact on paid care and informal care in relation to home automation was presented in six studies [Citation7,Citation20,Citation22–25]. Two studies, (a single case study of a woman with spinal cord injury [Citation20] and a multi-method study for individuals with functional limitations [Citation7] measured paid carer’s support pre and post home automation, and both studies reported a reduction in the need for care assistance after home automation. A further four studies adopted a qualitative approach and described outcomes for individuals with spinal cord injuries [Citation22–25]. Two studies suggested that home automation enabled individuals to be left alone for longer periods of time, which could potentially impact carer hours [Citation23,Citation24]. Furthermore, three qualitative studies described how home automation supported individuals to complete tasks independently, such as turning the television on and off, turning lights on and off, and using mobile phones to call and text. As a result of being able to complete these tasks individuals described how they felt less of a burden and how it meant that carers could spend time doing other tasks [Citation22,Citation24,Citation25].

Independence

Independence is having choice and control over your life by making decisions and not having to rely on others [Citation37]. Seven studies described the outcome of independence for individuals living with a disability using home automation [Citation7,Citation16,Citation19–21,Citation23,Citation24]. Four studies used surveys including several instruments to measure independence: the AQol-4D [Citation26]; Psychosocial impact of assistive devices scale (PIADS) [Citation38]; BI [Citation34]; and FAI [Citation35]. All four studies reported improved independence amongst participants with functional impairment, spinal cord injury and motor neuron disease because of having home automation [Citation7,Citation16,Citation19,Citation21]. Three studies [Citation20,Citation23,Citation24] that adopted a qualitative approach to understand the experience of individuals with spinal cord injuries found home automation provided feelings of independence. Home automation was described as enabling these individuals to do simple everyday tasks without relying on others which increased their sense of independence. Not being a burden on others was deemed important to participants and was often seen as more important than the personal independence they experienced [Citation20,Citation23,Citation24].

Autonomy

Although similar to independence, autonomy refers to self-governance, the capacity to control and make decisions, and is not solely about relying on others, as the term independence often refers to [Citation37]. Six studies identified autonomy as a potential outcome for people living with disability accessing home automation [Citation7,Citation16–18,Citation23,Citation24]. Three studies used standardised tools (PIADS [Citation38]; ARC [Citation28]; PWS [Citation29,Citation30]; ADL [Citation39]; IADL [Citation32] to measure autonomy and reported an increase in the sense of autonomy amongst participants with chronic stroke, motor neurone disease and down syndrome following the use of home automation [Citation16–18]. A further two studies adopted a qualitative approach and explored the experience of home automation by individuals living with functional limitation and spinal cord injury. Participants in all three studies reported that home automation had restored some of their autonomy and this improved their wellbeing [Citation7,Citation23,Citation24].

Mental health

Mental health is a state of wellbeing that enables individuals to manage stresses in life and is an important component of health and wellbeing [Citation40]. Six studies examined the link between home automation and the mental health of people living with a disability [Citation7,Citation16–18,Citation23,Citation24]. Of these six studies, four studies used quantitative standardised tools such as the AQoL-4D [Citation26]; PIADS [Citation38]; Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem scale (RSE) [Citation41]; World Health Organization Quality of Life – Bref (WHOQOL-Bref) [Citation42]; Short Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12) [Citation7,Citation16–18,Citation43]. All four studies reported that they found improvements in mental health after using home automation such as improved self-esteem, reduced anxiety and improved psychological wellbeing. Two of these studies compared individuals accessing home automation to a control group (no access to home automation) and both reported significant improvements in mental health in the home automation group compared to the control group although sample sizes were small (n = 8 and n = 40) [Citation17,Citation18]. Two qualitative studies reported that participants described improvements in mental health related to home automation [Citation23,Citation24]. One study reported that individuals experienced positive mental health due to the increased independence they had from using home automation [Citation24]. The other study described that being able to do things without asking a carer decreased frustration and improved participants’ sense of wellbeing [Citation23].

Social and community connectedness

Social and community connectedness is about the experience of belonging to a group, family or community and the relationships you have with other people and the wider community [Citation44]. Three studies examined how home automation could influence feelings of social and community connections [Citation7,Citation22,Citation24]. One study used a quantitative survey before and after home automation to measure the social isolation of individuals with functional limitations [Citation7]. Participants reported a reduction in social isolation and an increase in the number of close friends they had following home automation being installed due to it facilitating online social participation [Citation7]. Similarly, two separate studies exploring the lived experience of individuals with spinal cord injury using home automation both found home automation improved contact with family and friends [Citation22,Citation24]. The ability to access functions and applications facilitated connections to family and the wider community allowing for more regular contact [Citation22,Citation24]. Furthermore, home automation was also described as improving relationships with family and friends by reducing the reliance and demand placed on friends and family [Citation24].

Safety

Safety refers to the avoidance or reduction of harm from the environment in which the individual lives [Citation45]. Feelings of safety were explored as an outcome in four studies [Citation7,Citation17,Citation21,Citation24]. Three studies evaluated the benefits of home automation for individuals with Down’s syndrome, functional impairment, and motor neurone disease using surveys before and after the use of home automation [Citation7,Citation17,Citation21] with one study [Citation17] using a standardised tool; Inventory of Apartment Living Skills (IALS) [Citation46]. All studies reported that there were improved feelings of safety amongst participants when using home automation. One qualitative study explored the experience of individuals living with spinal cord injury using home automation and found participants felt safer [Citation24]. The security of having home automation made individuals feel more relaxed and secure, knowing they had the option of using home automation to contact people if needed and gave individuals the option of choosing to be alone if they wished [Citation24].

Discussion

This review included 11 studies and identified seven key home automation outcomes experienced by people living with a disability. Studies adopted both qualitative and quantitative approaches with six of the studies using standardised tools to measure the outcomes [Citation7,Citation16–20]. Studies were small, represented a heterogeneous population and seldom included a control group. This scoping review summarises the type of outcomes and findings of the studies but unlike a systematic review does not critically appraise study quality. Therefore, findings that home automation improved the various outcomes should be interpreted with caution.

Home automation appeared to impact on people’s ability to perform daily activities and this could increase feelings of independence. Home automation could also potentially enhance autonomy as individuals reported relying on others less and being able to complete tasks themselves that were previously completed by carers. Increased independence and autonomy positively impacted upon individuals’ mental health, and facilitated important social and community connections which could increase feelings of safety.

Individuals require certain needs to be met to experience a good quality of life [Citation47]. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs there are five categories of needs: physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualisation. If these needs are unmet individuals may experience anxiety, loneliness, low self-confidence, and lack of meaning in life. The findings from this scoping review suggest that the introduction of home automation may result in increased ability to meet basic needs through to the highest level of needs as per Maslow’s hierarchy, therefore potentially positively impacting the lives of individuals with a disability.

Overall, the study findings showed a range of outcomes associated with home automation experienced by individuals living with disability. Although home automation is not a new concept, advances in functionality and lower costs has meant that access to home automation has become more readily available [Citation7,Citation48]. In Australia the NDIA now supports people with a disability to access home automation through their support plan funding. However, it has been suggested that navigating the NDIA system to access funding is complex and presents many challenges [Citation7]. Therefore, this review could be a useful tool for policy makers to use to raise awareness of the potential outcomes of home automation of people living with disability.

Whilst an extensive search was conducted, we acknowledge that there were only 11 studies identified that reported outcomes of home automation for people with a disability. The studies found were both qualitative and quantitative, and no randomised controlled trials were identified. Despite this review suggesting that home automation can have a wide range of outcomes for people living with a disability, research is limited in this area which highlights the need for further research to be conducted. A possible explanation for the limited research is that home automation is a relatively new concept and the population of people with high levels of disability is relatively low. It would be expected over time that advances in technology and the increase in availability of funding would result in more research in this area.

Overall, these findings suggest the range of outcomes that may stem from home automation for individuals living with a disability and the range of benefits which could be experienced. Further research by the authors will build upon this evidence by conducting a social return on investment analysis to assess the impact of home automation for people living with a disability. This research will attempt to provide an in-depth understanding of the impact of home automation for people with a disability and also value the personal, community and societal outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings: ABS. 2019. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release

- World Health Organisation. Disability. WHO; 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Specialised supports for people with disability. AIHW; 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/supporting-people-with-disability

- Bierhoff I, van Beerlo A, Abascal J, et al. Impact and wider potential of information and communication technologies. In: Roe PRW, editor. Towards an inclusive future. Brussels, Belgium: East Sussex Press; 2007. p. 110–147.

- Haba CG, Breniuc L, David V. Developing embedded platforms for ambient assisted living. In: Dobre C, Mavromoustakis, C, Garcia N, Goleva R, George M, editors. Ambient assisted living and enhanced living. Environments: Elsevier; 2017. p. 211–246.

- Varriale L, Briganti P, Mele S. Disability and home automation: insights and challenges within organizational settings. Vol. 33. Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 47–66.

- Bridge C, Zmudzki F, Huang T, et al. Impacts of new and emerging assistive technologies for ageing and disabled housing, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. AHURI Final Report. 2021.

- Administration for Community Living. Assistive technology. 2021. https://acl.gov/programs/assistive-technology/assistive-technology

- National Health Service. Home adaptions for older people and people with disabilities. 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/social-care-and-support-guide/care-services-equipment-and-care-homes/home-adaptations/

- National Aged Care Alliance. Assistive technology for older Australians. NACA; 2018.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Meth. 2018;18(1):143–143.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Meth. 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Henley L. The assistive technology for all alliance Pre-Budget submission. AFTA; 2019.

- Covidence systematic review Software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; 2022.

- Callaway L, Tregloan K, Williams G, et al. Evaluating access and mobility within a new model of supported housing for people with neurotrauma: a pilot study. Brain Impair. 2016;17(1):64–76.

- Landuran A, Sauzéon H, Consel C, et al. Evaluation of a smart home platform for adults with Down syndrome. Assist Technol. 2022;1-11.

- Maggio MG, Maresca G, Russo M, et al. Effects of domotics on cognitive, social and personal functioning in patients with chronic stroke: a pilot study. Disab Health J. 2020;13(1):100838.

- Ocepek J, Roberts AEK, Vidmar G. Evaluation of treatment in the smart home IRIS in terms of functional independence and occupational performance and satisfaction. Comput Math Meth Med. 2013;2013:926858.

- Squires LA, Rush F, Hopkinson A, et al. The physical and psychological impact of using a computer-based environmental control system: a case study. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2013;8(5):434–443.

- Wallock KE, Cerny SL. Benefits of smart home technology for individuals living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Assist Technol Outcomes Benef. 2021;15(1):132–138.

- Hooper B, Verdonck M, Amsters D, et al. Smart-device environmental control systems: experiences of people with cervical spinal cord injuries. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(8):724–730.

- Myburg M, Allan E, Nalder E, et al. Environmental control systems–the experiences of people with spinal cord injury and the implications for prescribers. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(2):128–136.

- Verdonck M, Nolan M, Chard G. Taking back a little of what you have lost: the meaning of using an environmental control system (ECS) for people with high cervical spinal cord injury [article]. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(8):785–790.

- Verdonck M, Steggles E, Nolan M, et al. Experiences of using an environmental control system (ECS) for persons with high cervical spinal cord injury: the interplay between hassle and engagement [article]. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2014;9(1):70–78.

- Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The assessment of quality of life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(3):209–224.

- Parkinson S, Fisher G, Fisher J. The residential environment impact survey – short form (UK Version 2.2). 2011. www.moho.uic.edu/REISinformation.html

- Weymeyer ML. The arc’s self-determination scale: procedural guidelines. 1995.

- Lapierre S, Desrochers C. Translation and validation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales of Ryff. 1997.

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069–1081.

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. J Am Med Assoc. 1963;185(12):914–919.

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-Maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186.

- Granger CV, Gresham GE. Functional assessment in rehabilitation medicine. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1984.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

- Schuling J, de Haan R, Limburg M, et al. The frenchay activities index. Assessment of functional status in stroke patients. Stroke. 1993;24(8):1173–1177.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Informal Carers: AIHW; 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/informal-carers

- World Health Organisation. A glossary of terms for community health care and services for older persons. WHO; 2004. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/68896

- Jutai J, Day H. Psychosocial impact of assistive devices scale (PIADS). Tech Disabil. 2002;14(3):107–111.

- Shelkey M, Wallace M. Katz index of independence in activities of daily living. Home Healthc Now. 2001;19(5)

- World Health Organisation. Mental health: strengthening our response. WHO; 2022.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent Self-Image. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1965.

- World Health Organisation. WHOQOL-BREF 2004. https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National study of mental health and wellbeing. ABS; 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health care safety and quality. AIHW; 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/health-care-quality-performance/health-care-safety-and-quality

- Corbeil R, Marcotte A, Trépanier C. Inventaire des habiletés pour la vie en appartement. [inventory of skills for living in an apartment]. Groupe de recherche et d’étude en déficience du développement, French. 2009.

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50(4):370–396.

- Tune D. Review of the national disability insurance scheme act 2013: Australian Department of Social Services. 2019. https://www.dss.gov.au/disability-and-carers-programs-services-for-people-with-disability-national-disability-insurance-scheme/review-of-the-ndis-act-report