Abstract

Following four-months of ethnographic fieldwork among the young, self-employed craft workers in Jingdezhen, this article explores the diverse identities and emerging cultures associated with craft that differ from the popular imaginaries of craftspeople, or shouyiren, in the Chinese mainstream media that focus on the older generations. By conducting participant observation, in-depth interviews, and the diary method, I found that while the profiles of “craft workers” or “craftspeople” are favoured by the recent waves of self-employed craft workers in Jingdezhen, these workers do not fully identify as craftspeople, traditionally characterised by their professionalism, perfectionism, enthusiasm, and persistence; nor as artists. Instead, they are positioned in between different identities, such as traditional craftsman, workman, artist-crafts worker, and artist. I argue that the wavering between different identities according to the occasion and targeted audience not only allows self-employed craft workers in Jingdezhen to escape from the monotonous routines and patriarchal norms of the older generations’ craft conventions, but also facilitates a re-configuration of craft identities within a craft industry that is changing. Secondly, I found that creativity is emphasised in their self-positioning and becomes an alternative means of achieving recognition, status and mobility in Jingdezhen’s craft industry. Based on these discussions, the study provides a fuller picture of a new form of craft labour developing in Jingdezhen.

Introduction

Jingdezhen is a midland Chinese city known as the Chinese porcelain capital, with over 1,000 years of history of blue and white ceramic production.Footnote1 Independent craft workers used to be a marginal group within Jingdezhen’s state-driven ceramics industry, especially during the period of ceramic production in the 1960s and 1970s when most of Jingdezhen’s ceramics studios and workshops were incorporated into state-owned porcelain factories. It was not until the end of the 1970s when market-oriented economic reforms were implemented that the state-led manufacture system established under the socialist planned economy started to dismantle.Footnote2

Economic reform and marketisation in the 1980s led to increased privatisation and small businesses and workshops started to flourish. Since the 2000s, new waves of young craft migrants known as Jing drifters (jingpiao 景漂) have emerged: they are typically migrants, from within China and in some cases from other parts of the world; they are creative, independent and sometimes art-oriented; many of them have attained a higher education degree before coming to Jingdezhen, but not necessarily in a ceramics-related subject. When compared to the older generations, the new generation do not usually learn and practice ceramics through kinship ties, apprenticeships, or work experience in state-owned porcelains factories. Instead, they go to training courses, learn from other craft workers on site, or self-study. While these individuals are usually engaged in ceramic making, they don’t necessarily pivot to a craft-led career or hope to remain and establish themselves in the city. Some of them come to Jingdezhen for rest, or a gap year, and do not stay long.

This article charts the recent waves of younger generations of craft workers in Jingdezhen, and accounts for the diversification of craft labour in the city: while old titles and categories of craftspeople exist in the state-sponsored, traditional, and mass-produced ceramic production, a new creative, non-conformist, hipster generation has emerged. As my research demonstrates, this new group is negotiating and re-positioning their craft identities, reflecting changing patterns of craft labour in the Global South as well as the more general trend of increasing numbers of vocational migrantsFootnote3 and craft (micro-)entrepreneurs.Footnote4

My interest in the various categories and identities of craft workers started when I first met Xia’nan in Jingdezhen on 6 May 2020 who acquainted me with a variety of craft workers, including traditional craftspeople, individual craft workers, artists, family-size workshop owners, and ceramic enterprise directors. I was amazed by the diversity of the local craft population and how the narratives of the Jingdezhen craft workers, their craft-related titles and identities shift depending on the context of use and the audience, ranging from (traditional) craftspeople to artisans, artists, individual (creative) craft workers, and craft studio owners or ceramic enterprise directors. There was high mobility between these different identities and categories: I encountered former artisans who had built their brands and small workshops and individual workers who were either thinking of taking an artistic approach or converting their studios into small enterprises.

In my later interviews with younger-generation independent craft workers, I realised that despite the fact that the word used the public to refer to Jing drifters is shouyiren (手艺人, literal translation, hand art person), the English equivalent of “craftspeople” is a word that many of them do not identify with. At the same time, however, Jing drifters do not completely distance themselves from the term shouyiren, accepting the designation depending on the occasion.

Both the diversification and co-existence of different craft identities and the ambiguous attitude of different craft labour to defining themselves led me to question why self-employed craft workers emphasise one title or identity instead of others?; why they use different terms to identify themselves on different occasions when facing different audiences?; and how they navigate different categories of craft labour? By answering these three questions, this research investigates how the young self-employed craft workers position themselves in Jingdezhen’s craft world and negotiate and cement their identities. Perhaps more importantly, recognising the complexity of identity negotiation among the younger-generation craft workers helps build a fuller understanding of an emerging typology of craft labour and its associated cultures.

Fieldwork and Methodologies

I conducted my ethnography in Jingdezhen from 3 May to 29 August 2020.Footnote5 For most of my stay, I lived in an Airbnb accommodation owned by Mian, a self-identified “ceramic maker” (taoyiren 陶艺人). I visited the studios and homes of Jingdezhen’s craft workers on weekdays and frequented the ceramics markets on weekends and Monday mornings. Since mid-August 2020, I also learned basic ceramics-making skills from Yimu, who was based in Jinkeng village, a 20-minute ride from Jingdezhen.

As previously mentioned in the introduction, I started to notice the varied craft categories and identities from my initial fieldwork, and the conversations and observations in the studios, apartments, and markets of craft workers. I also found the issue of self-identification recurring in my initial interviews, and I included the questions regarding the self-identification for the later in-depth interviews and diary methods.

Specifically, throughout my 37 semi-structured in-depth interviews, I asked the interlocutor how they and the others address themselves and how they think of different craft identities; besides, I also selected four representatives to engage with writing diaries over a period of 12 weeks. In the last of these weeks, I asked them to produce a self-portrait to describe themselves.

In the following, I will begin with a review of diversifying craft identities, both suggested by the literature worldwide, and the particular Jingdezhen context. Then I will explore the identity navigations of young self-employed craft workers. Based on this discussion, I will delve into how young self-employed craft workers position themselves and highlight the importance of creativity within their practice. I will conclude by identifying their emerging cultures and characteristics that are distinct from that of previous generations.

Diversifying Craft Categories and Identities in the Changing Craft World

The question of craft identities is linked to the different ways craft labour has been organised and perceived. Howard Becker, in the 1970s, already suggested that the organisational form of the craft world was becoming more complicated and differentiated, dividing craft workers into ordinary craftspeople who try to do decent work and make a living, and the artist-craftsman with more ambitious goals and ideologies.Footnote6 Since then, the sociological, anthropological and history of art scholarships (mostly contextualised in the global north) have discussed the ambiguous boundaries between crafts and art, also, the transitionFootnote7 and power dynamicsFootnote8 between these two statuses.

Since the 2000s, with the rise of e-commerce, the creative economy, and the regeneration of the craft industry worldwide, scholars have identified emergent groups of craft workers and new forms of craft labour. For example, Susan Luckman, places craft in the contemporary creative economy, establishing the term “craft (micro) entrepreneurs” to describe entrepreneurship in crafts initiatives both on- and offline, focusing on craftspeople who have developed online businesses making and selling artisanal goods.Footnote9 Later, Trevor Marchand, in his ethnographic study of fine woodworkers based in London, coined the term “vocational migrants” to describe craft learners who decide to move from their original lines of employment and pursue a craft career. In his accounts, many these vocational migrants are attracted by a craft career because they expected it be a more rewarding way of working and living than what they were doing before. Footnote10

More recently, Jochem Kroezen et al. recognised the diversifying categories in craft from the perspective of organisational studies. They put forward four different models of craftwork including traditional craft, industrialised craft, technical craft, and creative craft work. In doing so, they showcased how these categories, in coordinating work, put forward different priorities and reliance on art, market, hierarchy, and community.Footnote11

These recent publications within craft studies demonstrate the complexity of craft identities that have emerged since 2000 that depart from traditional, labour-intensive stereotypes; they also further our understanding of craft-making via new identities: from labourers, artisans, and craftspeople, to entrepreneurs, designers, and artists.

Changing Craft Labour in Jingdezhen and Craft Identities in Use

Jingdezhen has experienced several drastic changes in the past century. When the People’s Republic of China was established, the workshops that comprised Jingdezhen’s ceramic industry were incorporated into the state-owned porcelain factories, and factory-assigned mentorship offered inexperienced workers intensive training with a strong focus on a particular (basic) industrial procedures or technique. In parallel to the factory-assigned mentorship, some masters would also teach people with whom they entertained social relations - or guanxi [关系] - in the mode of conventional apprenticeship, helping transmit skills of traditional fine art porcelain. As with the shortage of traditional artisans, the development of this guanxi-based mode was permitted and backed by the factories.Footnote12

Since the 1990s, China initiated a series of economic reforms and the state-owned factories started to shutdown. Many ceramic workers from the factories were laid off.Footnote13 Meanwhile, the resurgent private economy brought about several new organisational modes of craft work: such as those based on workshop (zuofang 作坊), the privately or individually owned business (geti gongshanghu个体工商户, Getihu for short), private enterprise (siying qiye 私营企业), and studio (gongzuoshi 工作室).Footnote14 In these new organisations, most of the workers had prior training and work experience in state-owned factories or came to Jingdezhen as ceramic apprentices through family networks.

More recently, the early 2000s witnessed the rise of self-employment in the Chinese labour market and the general trends of individualisation and individualism of Chinese society.Footnote15 There has been a growing number of more independently organised craft workers migrating from other cities: the Jing drifters (jingpiao 景漂) whose numbers, according to local media, have swelled to 30,000 people in the city each year.Footnote16

This younger generation of self-employed craft workers differ from previous generations in many ways. Many of the older-generation crafts workers are local citizens or came to Jingdezhen because of geographical proximity or through relatives’ social ties;Footnote17 they learnt ceramic skills through apprenticeships in the masters’ workshops and started their careers by working for their masters, as I was told by my interlocutors. In comparison, most younger craft workers since the 2000s began their craft careers on their own after having acquired university degrees, though not necessarily in ceramics. Longing for Jingdezhen’s ceramics traditions, creative culture, easy access to raw materials and labour, low living costs, and seemingly carefree environment, the recent wave have migrated to Jingdezhen either wishing to learn and practice ceramics, or to practice a lifestyle, or simply just to run away from the rat race.

This rising population has attracted scholarly attention in the last two decades. Here I do not intend to summarise what previous literature has covered, regarding the new generation of self-employed craft workers, rather, I would like to focus on what labels and identities they have adopted and recognised. My paper aims to provide new insights into complexities of labelling and identification that are less investigated in the existing literature.

There are a variety of terms in use to refer to the younger generation self-employed craft workers. Scholars have adopted terms such as artists (艺术家)Footnote18, (young) ceramist (陶艺家)Footnote19, Jing drifters (jingpiao 景漂)Footnote20, creative community (创意社群),Footnote21 emergent group (新兴群体)Footnote22, shouyiren and its derivatives such as student craftsperson (学生手艺人)Footnote23. Especially in Chinese scholarship, Jing drifters tend to become an umbrella term when referring to the new wave of self-employed craft workers. However, I argue that the use of the term Jing drifters, as it is promoted by the state, stems from the revival of the city’s ceramic industry. This new wave of self-employed craft workers, as will be shown later do not always align with the more established craft categories - artist, ceramist, and shouyiren – the later are less attractive to self-employed craft workers and do not reflect the profile of the new wave of craft labour in Jingdezhen. More works need to be done to conceptualise this emergent group and to understand the new characteristics of their approach to ceramic production.

Identity Navigations: “It’s Good to be a Craft Worker” – Craft Worker as a Favoured Identity

Tianyi was one self-employed craft worker who I interviewed in 2020 and she revealed to me how she would identify herself in public.

“Designer” is not the right word because I am not as good as a designer. A privately or individually-owned business? Well, that’s just one category. A freelancer (自由职业者)? This sounds too idle (闲散) and people may think I am doing nothing (无所事事) and maybe it’s not that good. Maybe a craft worker (手工艺者). I more often say I am a craft worker. It’s good to be a craft worker. It gives people a very different feeling.

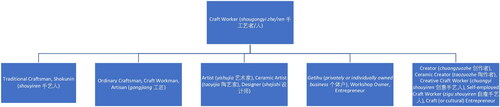

As suggested by Tianyi’s account, different types of craft workers exist in Jingdezhen. While Tianyi thought herself not qualified for being a “designer”; she also did not feel attached to the business-oriented category of getihu (meaning “privately or individually-owned business”) or “freelancing” because of its connotations of an overrelaxing lifestyle and marginalised social positionality in ChinaFootnote24 ().

Among these categories, Tianyi, a novice in the industry, preferred the word “craft worker”, the umbrella term for traditional craftspeople (shouyiren), and craft workman or artisan (gongjiang), as shown in , because it signals difference for her. It is worthwhile thinking about how the profile of “craft worker” echoes that difference. With increased media exposure and China’s re-emphasis on reviving traditional skills and cultures, crafts workers have gained recognition. With the cultural legitimacy embedded in crafts as a national treasure and tradition,Footnote25 the word “craftsmanship” has also been romanticised to the extent that the Chinese public might imagine that self-employed craft workers lead a traditional and simple life, which is not always the case. Their presumed non-industrial and often nostalgic countryside lifestyles, as Sun Facheng described, present seemingly authentic alternatives to Chinese urbanisation and the neoliberal labour market where productivity is prioritised, and consumerism prevails.Footnote26 Not surprisingly, the romantic associations of “craftsmanship,” attract many creators who identify themselves and others with this lifestyle perceived to be removed from mechanised production for commercial or aesthetic reasons. In a sense, Luckman’s reframing of craftspeople as craft micro-entrepreneurs, immersed in cultivating a profile of an alternative, often environmentally attentive lifestyle, is closer to the reality of Jing drifters.Footnote27 Similar to Luckman’s research participants – craft workers on e-commerce platforms such as Etsy – new wave of craft workers in Jingdezhen have a similar need to re-iterate the fiction of the romantic craftsperson to appeal to their market, while insisting on their professional disposition and personal skill.

Neither “Shouyiren” nor “Artist”: Identity Navigations

While the profile of “craft worker,” or more specifically shouyiren, has been favoured by the public and the craft workers themselves, the use of this term does not always grasp the full diversity of the self-employed craft population of Jingdezhen. There is a mismatch between public perception and the reality on the ground: self-employed craft workers position themselves in between various identities. For example, when I asked Zilin, an individual craft worker in his 30s, whether anyone called him shouyiren (craftsperson), he replied:

I don’t think I am a shouyiren. In my understanding, shouyiren are those who practice one technique or make one [type of] work for ten years. This person can be called a “shouyiren.” We are not comparable to them. Our work is just related to shouyiren’s. But whether we are shouyiren or not is a question. I think a more appropriate descriptor for me is a “creator”. [chuangzuozhe 创作者]

Zilin added that “They [the shouyiren] have fixed time to delve into one thing every day and make one thing for ten years. In such a sense, I am not a shouyiren. How could I be?” In other words, Zilin thinks of himself being less invested in a single practice, working hard instead on a range of creative work.

This contrast made by Zilin, between a regular and diligent craft worker like himself, and shouyiren, suggests a particular understanding of this category in Jingdezhen. Although shouyiren literatally refers to the craft workers (shougongyiren 手工艺人) in general, it connotates the worker’s expertise and focus on one particular technique that is usually done by hand over a large period of time, suggestive of the traditional-style craftsman.Footnote28. In other words, shouyiren, in the eyes of these self-employed craft workers, are known for their concentration and consistent reliance on particular techniques over their lifetimes. During my fieldwork, I find that this interpretation is particularly prevalent among the younger generation of craft workers.

When I was in the university, I was so into the idea of choosing one career and fulfilling it for a lifetime [择一事, 尽一生; literal translation: choose one thing, complete the life.], You know, the university education and some social media promote this value. I think I had been somehow “brainwashed” and sometimes feel guilty for not insisting on being a shouyiren.

(Mian, in her 20s, individual craft worker, single)

Mian’s accounts suggest that some self-employed craft workers are heavily influenced by the values of “being a shouyiren” in their education. Interestingly, I also found that, as they embarked on their craft career, they have become more critical of recent discourse about craftsmanship. First, they realise that while shouyiren’s approach has respectful qualities such as perseverance and determination, it is not necessarily creative and innovative. Some experienced craft workers point to the limits embedded within the traditional norms, such as repetitions and non-creative moments throughout the conventional apprenticeship system and during the traditional learning processes, especially in the Japanese models.

Second, some younger generation of craft workers are also aware of the entrenched hierarchies. Especially in the market of traditional ceramics, the institutionalised master system (dashi tixi 大师体系) at both provincial and national level still prevails. In such system, dashi (master, 大师) is respected for their inheritance of traditional skills and excellent artisanship and are recognised at local or national level and have official recognition such as provincial or national Master of Chinese Arts and Crafts (shengji/guojiaji gongyi meishu dashi 省级/国家级工艺美术大师) similar to Living National Treasures (Ningen Kokuhō 人間国宝) in Japan.Footnote29 However, the entry to becoming a master is so high for young self-employed craft workers.

Realising that if aligning oneself with shouyiren, one has to comply with the expectations attached to this label in their daily practices, some self-employed craft workers prefer to not be associated with this identifier despite their enthusiasm for hand-crafting. In comparison, craft workers who are more technique-oriented and who are family-run workshops responsible, are more willing to be considered shouyiren. That is, they recognise that the lifestyle of shouyiren is fulfilling and enduring but not always creative; and are willing to admit that their work involves some non-creative elements.

While most young self-employed craft workers do not embrace the title “craftsperson”, they do not completely distance themselves from the term. In fact, the Japanese equivalent of craft, (shokunin 職人), craftsmanship, and craftsmanship spirit, (shokunin seishin職人精神), has been much promoted in Chinese social media as an attractive term in the craft workers’ social circles. As Aoyama Reijiro argued, outside of Japan, values that stress professionalism and an appreciation of apprenticeship do not necessarily lead to following a rigid system, rather, they present a culture known for professional competence, reliability, and work ethic.Footnote30 Similarly, the craft workers attached to the shouyiren identity do not always need to tackle the pressures from the industrial conventions nor the pains from the rigid apprenticeship system themselves. “Craftsperson”-related labels can add value to their careers, lives and even social status, because under such a name, they are recognised as professional, determined, authentic, and different from the masses.

In consequence, young self-employed craft workers tactically position themselves and their work and sometimes appropriate the idealised notions of “craftsmanship” and “craftspeople” so as to better satisfy their audiences and their own creative trajectories. For example, while they do not identity with shouyiren in daily life, in some social media and especially in some media reportage, they accept the use of keywords or hashtag related to “craftsmen”.

Another label that seemed particularly unpopular among my interviewees was “(ceramic) artist” (taoyijia 陶艺家). To return to Zilin:

I don’t normally give myself any title. But if I had to give one myself, I would be more willing to call myself a creator [创作者]. There are people calling me a ceramic artist [陶艺家]. That’s not my job to handle this. But I would advise them not to use that word. Maybe in their perception, I am at this stage [of a ceramic artist], but I don’t think I’m a ceramic artist. I am just doing what I love, just creating [创作]. As for a ceramic artist, I don’t think I am qualified for that. I’m still young [laughs].

Despite doing creative work, young self-employed craft workers like Zilin think of themselves as too young to merit the title of ceramic artist. While their reservations may be self-effacing, such attitudes also suggest the rigorous credentials and time commitment required for this designation of “artist”. While in the English-speaking context, an artist can loosely refer to anyone who creates, and “everyone is an artist” is a frequent discourse, the Chinese equivalent of “artist,” yishujia, has more connotations. For example, a common understanding among Jingdezhen’s young craft workers is that artists should not limit their medium of expression. Rather than focusing on one material (ceramics), they ought to engage every appropriate material, working toward the unrestrained personal expression. During my fieldwork interviews and observations, I also found that in Jingdezhen ceramic artists are expected to address aesthetical issues as well as the philosophical and spiritual values of their work; more practically, they also achieve greater public recognition; many of them have held solo exhibitions in established galleries or have had media interviews. In comparison, the identifier “creator” removes the need to necessarily engage with different materials, or to be philosophical and highly recognised by the traditional art world.

These characteristics attributed to “artist” in the Chinese language may explain why Zilin preferred considering himself as a creator, a term that emphases the creative work itself rather than one’s position in society and levels of recognition.

Zilin is a representative self-employed craft worker who is positioned in between different identities of craft labour. This requires him to negotiate his relationship to craft production, authenticity, traditions, creativity and autonomy, etc. This in-betweenness of Jingdezhen’s self-employed craft workers offers them a getaway from both the monotonous routines and patriarchal traditions of the older generations’ craft, and the art world; perhaps more importantly, this in-betweenness suggests alternatives to craftwork practices and lifestyles of the craft workers, as I will explain later.

Creativity-Led Self-Positioning

While Zilin agreed that craft workers like him should be able to find a more appropriate self-identifier to offer the general public, he kept using general terms such as “creator” (chuangzuozhe 创作者), “ceramic creator” (taozuozhe 陶作者) and “ceramic maker” (taoyiren 陶艺人) throughout our conversations.Footnote31 These terms thus made me ask: What are the qualities and features of the terms “creator” and “ceramic maker” that make them more popular? And what were the features and styles of the young self-employed craft workers in Jingdezhen.

When studying craft work in the purple clay (zisha 紫砂) workshops in Dingshu,Footnote32 Yixing, another Chinese ceramic town, Geoffrey Gowlland highlights fengge (style风格) as being fundamental for zisha artisans in the contemporary context.Footnote33 Similarly, in Jingdezhen, for young craft workers, developing one’s own distinctive style, is said to be important, helping to distinguish oneself from other ceramic workers; and in mass consumer market style stands out. While in Gowlland’s accounts, the pursuit of fengge in Yixing links to an emphasis of individual characters and experience, authenticity, and sometimes insistence on traditional skills, among the young self-employed craft workers in Jingdezhen, the debate over having a style or not inevitably involves a discussion of being creative or not, especially whether or not work is distinctive from the most traditional or dominant style. In other words, one essential barometer of having a style in Jingdezhen is “creativity.”

(photos taken between May and December 2020) provide an indication of what creative work means in Jingdezhen. As shown by the photos above, there is great variety in works made by the self-employed craft workers: there are utilitarian and daily ceramics such as bowls, plates, mugs, and vases, and some are more decorative and have non-traditional figures (as in ), some possess a more studio-based or art-oriented style (as in ); in addition, there are also some less utilitarian ceramic artefacts that are more unconventional ceramic artefacts (as in ); besides, few young self-employed craft workers also make ceramic wares of traditional shapes such as tea wares (as in ), but these wares can be considered creative if they possess new or unconventional (detailed) designs. Footnote34

Fig 1 Ceramic wares including plates and chopstick holders with decorative patterns, in a stall of Taoxichuan Creative Market, August, 2020. Photo taken by the author.

Fig 2 A series of ceramic wares and artistic works by an independent craft worker and artist in their local ceramics studio and shop, May 2020. Photo taken by author.

Fig 4 Planet-like ceramic containers by an independent craft worker in a local ceramic and craft shop, July 2020. Photo taken by the author.

Fig 5 A set of ceramic tea wares by an independent craft worker in their ceramic studio, June 2020. This set is in traditional shape but with innovative blue glaze. Photo taken by the author.

These works can be considered “creative” because they incorporate innovative ideas in terms of design, shape, colour, pattern, and concept; and because they do not follow an entirely traditional approach. In fact, during my fieldwork, I often heard self-employed craft workers use the following binaries when describing craft works: creative (chuangyi 创意) versus traditional (chuantong 传统); creations (zuopin 作品) versus products (chanpin 产品), creation (chuangzuo 创作) versus fulfilling the order (jiedan 接单) or work (gongzuo工作).

Being creative is not just about the work produced; it is also about process. Especially the self-employed craft workers in their early careers still prefer a largely handmade production process. Although they are not necessarily in charge of all steps of production, they usually keep the most significant procedures of their craft-making to be handmade by themselves.

When developing their approaches to work, the craft workers were often worried about the repetition involved in producing the same design and the experience of time when fulfilling batch orders. As Mian, stated:

I don’t want to keep the approach of fulfilling orders anymore. A local craft store has bought some oval plates of mine. People who are not ceramic workers might think that’s a nice deal. But I think over it and feel that this kind of work leads to many repetitions. There is nothing wrong with repetition, but I just do not like it. Now [after drawing the same pattern again and again…] I feel very annoyed when I see this [oval plate] pattern.

Similarly, in response to the question I asked people to respond to in their diaries “What was the most fulfilling or creative moment during the past week?” the diarists often wrote about being inspired, experimenting, and creating. They also frequently noted down the concerns of their works “not being creative enough” or were “mediocre.” “Creation” is key to the sense of fulfilment and accomplishment for young self-employed craft workers. Accordingly, in terms of their working ethos, being a creator is recognised as more important than being just a worker of crafts.

However, because of limited initial funds, and a lack of regular platforms and sales agencies, early-career craft workers often have to fulfil (large-volume) orders to secure income. While orders from regular customers usually maintain their production and sales for a period, it inevitably leads to repetition. Different from the private entrepreneurs in Jingdezhen of the 1980s and 1990s whose business models were structured around high-volume output, many young craft workers easily tire of extended periods of repetitive and monotonous work. They are also concerned that producing in bulk challenges their hand-making efficiency, or that they have to coordinate with demanding customers. Nevertheless, because taking orders promises an assured income, some craft workers eventually prioritise that in their careers. Others set a goal to shift from this mode as their career progresses. Generally, when making products, self-employed craft workers might have to defer to customers’ requirements for practical reasons, but they consider their own unrestrained works as more authentic and inspirational.

Although the differences between these modes are not always absolute as the generalisation might suggest, the preferences of the new generation place an emphasis on “being creative.” This resonates with the characteristics of the “vocational migrant” as Marchand has described in his research within a small community of fine woodworkers training at a London-based vocational college. Marchand found that vocational migrants accept the prospect of less lucrative careers and see the value in woodwork as fulfilling the basic human needs of engaging in creative production. While Marchand also showed that money was still a concern for trainees, both my case and Marchand’s suggest an archetype of craft labour that does not prioritise financial success.Footnote35

Emerging Cultures of the Self-Employed Craft Workers

The differences between Jingdezhen’s self-employed craft workers and the other categories of craft workers are more apparent when considering their lifestyles and cultures. From my research, the younger generations appear diverse and fastidious in their daily aesthetics, routines, and (cultural) consumption. Alongside a consideration of the aesthetics in their craft, many are concerned about their own presentation, including their clothing and home decoration. Some of them prefer Japanese designs, such as the Muji brand or Yamamoto Yōji; others preferred a traditional Chinese clothing style of hemp and cotton, as Fan Zhen also reported in their article on young craft self-employed workers.Footnote36 Some embrace a hipster or hippy style, leaving stains from their work on the second-hand or vintage clothes that they wear. These styles might be described as natural, simple, authentic, niche, and subcultural, reflected in their working and living space by the prevalence of self-grown plants and flowers, with randomly displayed stones and ceramic fragments found in the woods or bought from the shard market.Footnote37 Many lead a frugal life, characterised by a do-it-yourself mentality and practices, home cooking, and second-hand purchases.

Although this preference for “nature”, “simplicity”, and “self-sufficiency” partly results from low and unstable income, it also signals a strong stylistic preference. In part, the images of young craft workers are favoured by their audience and consumers because their authentic representation differentiates from the capitalist society and provides imagination for a non-conspicuous and consumerist life. In fact, the preferences for authenticity and simplicity also echoed profiles of the traditional craftspeople and their work-and-lifestyles. This finding can relate to Luckman’s observations of the aestheticisation and romanticisation of craft workers’ presentation on Etsy platformsFootnote38 ().

Fig 6 Coffee setting behind a stall in Letian’s weekend creative market, June 2020. Photo taken by the author.

Another interesting trend is the emergent cultures of the young-generation craft workers such as tea and coffee drinking. In almost all of my interviews in Jingdezhen, the craft workers served me several rounds of Chinese tea, often in the tea wares made by themselves. On more informal occasions, we drank hand-brewed coffee, craft beer, or gin. Before an interview, some interviewees would ask about my personal preference for tea or coffee, then they would select a suitable type for our conversation. During and after the interview, we sometimes discussed our habits of drinking tea or coffee or exchanged our brewing routines ( and ).

When Holt Robin and Yamauchi Yutaka observed (2018) the interactions between Japanese sushi chefs and customers, they argued that the questions about drinks to accompany sushi posed by the chefs to the customers can become a matter of judgment. In my encounter with these craft workers, conversation on tea and coffee meant not to be like tests, but my managing the information exchange indeed initiated deeper discussions.Footnote39 Surprisingly, drinking and enjoying fine tea was not very popular in Jingdezhen until the recent decade, and neither coffee, craft beer, nor gin was local beverage, but they have become so enmeshed in the craft workers’ daily lives. I once encountered a friend of Yimu reading The Classic of Tea behind his creative market stall. After hearing my praise, he shyly explained that it was because he made teapots that he felt the need to know more about tea. However, I argue that the knowledge of tea and being able to appreciate it, serve and talk about it is also a cultural capital, or more precisely an embodied one, as it suggests an asset of knowledge and experience.Footnote40

The understanding of tea and the expertise in tea brewing add to the credibility of the craft workers who deal with the related ceramics wares; it can also be a presentation of their (good) taste. In this sense, this cultural capital helps them gain more recognition and contributes to their social mobility in the craft world. Significantly, these lifestyle choices are intimately connected to the aesthetics and values of craft creation. Tao, a self-identified individual craft creator and artist, once told me how his older friends have influenced his creation, and also mentioned tea drinking.

My earliest works were quite western, but they [my old friends] told me about classical Chinese stuff, including drinking tea… I started drinking tea relatively early, in 2005, because they were all drinking tea. I naturally accumulated [my knowledge and habits], I saw a lot of good things, and I was willing to fiddle, think, and read. Then I became who I am now. They have directed my thoughts and personality… If I made something that sells well [很卖的东西], I would feel embarrassed – It will be a shame. It’s like I am already at this level. If I go down, I will just lose face.

Tea drinking has become a part of Tao’s lifestyle and is entwined with his knowledge and creation. People who share similar interests not only influence each other’s daily habits but also their creative approaches. Through these shared common understandings and routines, aesthetical choices, and holistic lifestyles, self-employed craft workers have formed a sense of community as well as culture, distinguishing them from the traditional ceramic workers and craftspeople. While the latter are characterised by their insistence on and practice of the traditional values of craftsmanship and often lead to a more traditional work and lifestyle, the self-employed craft workers are more open to non-mainstream aesthetics and lifestyle, such as recent emerging subcultures like hipsters who resist the productivity-driven neoliberalist life. China has witnessed the rise of the buzzword “lying flat” (tangping 躺平) since 2021 to refer to the retreat and withdrawal from (self-)exploitation in the labour market, and fierce social competition.

I argue that as their shared cultures emerged and developed, the sense of community among young craft workers has strengthened. While they still belong to Jingdezhen’s broader craft communities as their studios are located in the same craft neighbourhoods and districts and they frequent the same craft fairs. But their presentation and intended audience are different from those more established and traditional practitioners.

On most occasions, the people I interviewed for this research accepted the term Jing drifter, which is widely used in official narratives, to identify themselves. Although this state-promoted term highlights “entrepreneurship” which has not been always favoured by individually-based craft workers as a long-term goal, it does indicate the status of young craft workers as migrants to the city. On many other occasions, having negotiated with and rejected various identity terms, they mostly align themselves with the status of being creative craft workers and seek to embrace more specific and distinguishable words for self-identification such as “(ceramic) creator”.

Conclusion

In the process of investigating how the recent young self-employed craft workers in Jingdezhen waver between different craft identities I have found that a diverse set of craft labour categories have emerged and developed in this traditional craft town (as shown in ). While the emerging craft work, lifestyles and identities create new dynamics in crafts as a form of cultural production in China, there nevertheless remains an egalitarian discourse around the diverse identities of Jingdezhen’s craft workers. That is to say, each identity that is chosen is respected for different reasons. For example, traditional craftspeople stand out for their expertise in traditional techniques and perseverance. Ordinary artisans or workmen are characterised by their consistency and the machinery they use during the ceramic-making process a technical expertise that continues to impress the younger generation of Jingdezhen’s craft workers. Artists emphasise the artistic value and philosophies of their work and more often insisted on producing their products entirely by hand,Footnote41 and the entrepreneurs are admired for their innovative potential and business capacities. The recent waves of young self-employed craft workers, the Jing drifters, find a place within this matrix, praised for their creativity, emergent knowledge, lifestyles, and cultures. The self-employed craft workers have attempted to distinguish from the existing categories, for example, by using terms such as creator, ceramic creator and ceramic maker; terms which suggest working approaches that prioritize creativity along with the new lifestyles and culture.

The shifting identities of craft workers within the well-known craft town of Jingdezhen with historical craft traditions reflect the contemporary diversification of craft labour, a representative of a Global South context of craft studies. With the emphasis on creativity and their emerging cultures, the younger generations of craft workers in Jingdezhen seek occupational and alternative social identities to those of the traditional craftspeople and artists. In this process, and through a negotiation of the plurality of identities within this ceramic centre, they also wish to achieve recognition and status in Jingdezhen’s craft world.

Acknowledgments

I owe my greatest gratitude to all my research participants, interlocutors, and friends in Jingdezhen. I am also very grateful for the comments and suggestions offered by the editors and reviewers of the Journal of Modern Craft, as well as those put forward by the commentators in Crafts Studio’s sixth online workshop. My thanks also go to Professor Christel Lane’s early review and encouragement. Last but not least, I would like also to acknowledge the Department of Sociology of the University of Cambridge for their fieldwork funding.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ruoxi Liu

Ruoxi Liu is a PhD candidate at the Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge. Her research focus has been on the intersection of self-employment and cultural production in a developing context, such as in China. Her research interests also include craftsmanship, authenticity, subculture, decentralisation and alternative lifestyles.

Notes

1 Fang Lili, chuantong yu bianqian: Jingdezhen xinjiu minyaoye tianyekaocha [Tradition and Changes: Investigation into the History of Jingdezhen’s Folk Porcelains] (Nanchang: Jiangxi People's Publishing House, 2000).

2 Yawen Xu, “Craft Production in a Socialist Planned Economy: The Case of Jingdezhen’s State- Owned Porcelain Factories in the Mid to Late Twentieth Century,” Journal of Modern Craft 15, no. 1 (2022): 25–41.

3 Trevor H. J. Marchand, The Pursuit of Pleasurable Work: Craftwork in Twenty-First Century England, Vol. 4 (Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books, 2021).

4 Susan Luckman, Craft and the Creative Economy (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

5 My fieldwork in Jingdezhen is part of my larger PhD research on independent cultural workers in China, which has received approval from the Sociology Ethics Committee of the University of Cambridge and satisfied the guidelines of the ESRC Framework for Research Ethics. Considering the risks some independent communities and artists may face after the exposure, all the names of the research participants and the authorships of the works in this paper in illustration have been anonymised.

6 Howard S. Becker, “Arts and Crafts,” American Journal of Sociology 83, no. 4 (1978): 862–889.

7 Ibid.

8 Christina Hughes, “Gender, Craft Labour and the Creative Sector,” International Journal of Cultural Policy 18, no. 4 (2012): 439–454.

9 Luckman, Craft and the Creative Economy.

10 Marchand, The Pursuit of Pleasurable Work.

11 Jochem Kroezen, et al. “Configurations of Craft: Alternative Models for Organizing Work,” Academy of Management Annals 15, no. 2 (2021): 502–536.

12 Xu, “Craft Production in a Socialist Planned Economy.”

13 Maris Gillette, China’s Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

14 The privately or individually owned business (getihu个体户) are different from private enterprises (siying qiye 私营企业) in the Chinese categorisation of economic entities. Getihu is a registered business but not a company. Getihu is usually small-size and faces easier registration procedures and lower taxes than private enterprises.

15 According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, self-employment refers to earning income directly from one's own business, trade, or profession rather than as a specified salary or wages from an employer. In China, there is no official definition of self-employment. Freelancing (ziyou zhiye自由职业) is a more popular Chinese term for this status.

16 Guangming Online, “景漂”, 扮靓千年瓷都的新文艺群体 [“Jing Drifter”, a new literary and artistic group that shines the thousand-year-old porcelain capital]. Guangming Online Website, 2020, https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2020-10/21/nw.D110000gmrb_20201021_1-07.htm, (accessed December 2, 2021).

17 Xu, “Craft Production in a Socialist Planned Economy.”

18 Gillette, China’s Porcelain Capital; Danwei Wang, “chuangxin yu chuantong ziyuan de liyong – Jingdezhen ‘Laochang’ nianqing taoyijia gongzuoshi weili” [Innovation and Take Advantage of Traditional Resources – Case Study on Young Ceramists’ Workshops of LaoChang in JingDeZhen],” Master’s dissertation (Chinese National Academy of Arts, 2015). Zhu Huiqiu, Wu Xudong and Dong Liang, “lun ‘jingpiao’ yishujia dui dangdai Jingdezhen taociyishu de tuidongzuoyong” [Critique on “Jing Drifter” Artists’ Impetus for Contemporary Jingdezhen Ceramic Art], Jingdezhen Ceramics 6 (2015): 1–2.

19 Gillette, China’s Porcelain Capital.

20 Ibid; Songjie Li, “‘Jingpiao’ he Jingdezhen dangdai taoyi – yi Letiantaoshe chuangyishiji wei anli fenxi” [“‘JingPiao’ and Jingdezhen Contemporary Ceramic Art: Taking Letian Pottery Workshop Creative Bazaar as Analysis Case”(Sic)],” 内蒙古大学艺术学院学报 [Journal of Art College of Inner Mongolia University] 11, no. 3 (2014): 24–33; Wei Qun and Zhu Yunli, “ ‘Jingpiao’ wenhua xianxiang dui Jingdezhen taociwenhua chanye de yingxiang yanjiu’ [Research on the Influence of “Jing Drifter” Cultural Phenomenon on Jingdezhen Ceramic Cultural Industry], Ceramics (Ceramic Culture) no. 7 (2019): 72–74; Zhu Huiqiu and Wu Xudong, “‘Jingpiao’ xianxiang yu Jingdezhen taociwenhua de yinguohudong yanjiu” [Research on the Causal Interaction between “Jing Drifters” Phenomenon and Jingdezhen Ceramic Culture], Jingdezhen Ceramics (Research and Discussion), no. 5 (2018): 6–9. Zhu Huiqiu and Wu Xudong, “chuancheng yu chuangxin kunjing zhong: ‘Jingpiao’ zhuli Jingdezhen taocichanye zhuanxingshengji yanjiu” [In the Dilemma of Inheritance and Innovation: Research on the Impetus of “Jing Drifters” for the Transformation and Upgrading of Jingdezhen Ceramic Industry], Jingdezhen Ceramics, no. 2: 1–3.

Zhu Huiqiu, Wu Xudong and Dong Liang, “lun ‘Jingpiao’ yishujia dui dangdai Jingdezhen taociyishu de tuidongzuoyong” [Critique on “Jing Drifter” Artists’ Impetus for Contemporary Jingdezhen Ceramic Art], Jingdezhen Ceramics, (2015): 1–2.

21 Xiaolu Lu, “lun wenhuachuangyi shequn dui tese wenhua chengshifazhan de yiyi ji lujing – yi Jingdezhen Letian chuangyi shiji weili” [Cultural Creativity Communities and Development of Characteristic Cultural Cities: A Case Study of Jingdezhen Letian Creative Market],” 浙江工业大学学报(社会科学版)[Journal of Zhejiang University of Technology (Social Sciences)] 15, no. 2 (2016): 135–147.

22 Yaxing Wang, “taoci yishugongzuoshi zhong de xinxing qunti” [The Emerging Group of Ceramic Studio-Case Study of Jingdezhen’s University Graduates’ Studios],” Master’s dissertation, Chinese National Academy of Arts (2012).

23 Fan Zhen, “xuesheng shouyiren qunti yanjiu” [A Study on Students’s Handicraft Groups] Master dissertation (Jingdezhen Ceramic Institute, 2019).

24 Freelancers, or ziyouzhiye (自由职业) in the Chinese context, on one hand, signals independent and flexible working features of the self-employed workers (particularly in the internet-aided literature and design industry); on the other hand, may suggest informality and precarity. Especially in post-socialist China where the labour market policies and welfare policies are still employee-oriented, independent workers have been long marginalised and sometimes stigmatised in the public discourse.

25 Dorinne K. Kondo, Crafting selves: Power, Gender, and Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

26 Sun Facheng, “dangdai yujing xia minjian shougongyiren de shenfen zhuanxiang yu qunti tezheng” [The Identity Transformation and Group Characteristics of Folk Craftsmen in the Contemporary Context], Folklore Studies, no. 2 (2015): 61–65.

27 Luckman, Craft and the Creative Economy.

28 Other relevant terms to shouyiren include Jiangren (匠人, artisan, literal translation: craftsperson/carpenter, person), yiren (艺人;literal translation: art, person) and gongjiang (工匠;literal translation: work, craftsman/carpenter) can be loosely translated as “artisan,” and gongjiang emphasises the professional’s technical skills

29 Kondo, Crafting Selves.

30 Aoyama Reijiro, “Global Journeymen: Re-Inventing Japanese Craftsman Spirit in Hong Kong,” Asian Anthropology 14, no. 3 (2015): 265–282.

31 On a revisit of the Jingdezhen field in August 2023, I found the increasingly popular use of zuozhe “creator/author” [创作者/作者] when referring to the younger-generation creative craft workers.

32 Dingshu, Yixing is a Chinese city known for its purple clay wares production. Used typically for tea wares, purple clay wares are considered literati items and have a relatively high price in the Chinese ceramics market.

33 Geoffrey Gowlland, “Style, Skill and Modernity in the Zisha Pottery of China,” The Journal of Modern Craft 2, no. 2 (July 2009): 129–141; Geoffrey Gowlland, Reinventing Craft in China: The Contemporary Politics of Yixing Zisha Ceramics (Canon Pyon: Sean Kingston Publishing, 2017).

34 Following the requirement of the ethics guidelines for my research by my department, I keep the anonymity of the authors of the ceramic work shown in this paper.

35 Marchand, The Pursuit of Pleasurable Work.

36 Fan, “xuesheng shouyiren qunti yanjiu” [A Study on Students’s Handicraft Groups].

37 The Jingdezhen shard market is officially known as the Porcelain and Antiques Market. Open Monday early mornings, it features stalls for antique porcelains and their replicas (Gerritsen, 2020).

38 Luckman, Craft and the Creative Economy.

39 Robin Holt and Yutaka Yamauchi, “Craft, Design and Nostalgia in Modern Japan: The Case of Sushi,” in The Organization of Craft Work, eds. Emma Bell, Gianluigi Mangia, Scott Taylor, and Maria Laura Toraldo (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2018), 20–40.

40 Pierre Bourdieu, “Knowledge, Education, and Cultural Change” in Sociology of Education, ed. Richard Brown (London: Routledge, 1973), 71–112. Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Economic Life, ed. Richard Swedberg (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1986), 241–258.

41 Fan, “xuesheng shouyiren qunti yanjiu” [A Study on Students’s Handicraft Groups].