I can't remember how Jackie Stedall and I first met; but it must have been at a BSHM event, probably in about 1997. At that point she was just beginning a PhD on John Wallis's 1685 Treatise of Algebra under John Fauvel at the Open University; I was a postdoc at Oxford with a project on Babylonian scribal education in the eighteenth century bc. She was in her late 40s, with a family and a long and varied career; I was two decades younger, single and single-mindedly on the academic treadmill. On the face of it, it was an unlikely basis for a long-term working relationship, let alone the great friendship it grew into.

Our main point of contact, at least in the early years, was the BSHM. In the late 1990s and early 2000s we both served various roles on Council. By 2002, we were editing the society's Newsletter together. The Newsletter was the precursor to the BSHM Bulletin. It had been set up by Ron Gowing in 1986, fifteen years into the society's foundation, as a manually typed, mimeographed flyer posted to members three times a year. It originally consisted of news of meetings, recently published books, and other ‘items of interest to members’ but evolved into a more substantial publication under the editorship of John Fauvel, with reports of conferences, book reviews, abstracts of journal articles, and regular features such as ‘sundial corner’ and the ‘mathematical gazetteer’. After John's untimely death in 2001, June Barrow-Green and I held the editorial reins for a few issues but Jackie was soon persuaded to take on the task.

We quickly agreed a division of labour: she was to be the managing editor, soliciting content and handling submissions; I was nominally the production editor, in charge of proofreading, typesetting and printing. But in fact we each ended up doing a bit of both. (The membership secretary handled postage, thank goodness.) It helped that by this time we were academic next-door neighbours on Oxford High Street, Jackie at Queen's and me at All Souls, but much got done at home in the Cotswolds (Jackie in the west, me in the east) and by email and the internal university mail. We soon discovered that it was great fun to do this mundane, often fiddly and sometimes thankless work as a team. We could (and did) laugh at the more ridiculous aspects, groan together about recalcitrant contributors, share the pleasures of otherwise undetectable mini-triumphs such as finding the perfect cover image.

This extract of an email from Jackie, sent while she had a visiting lectureship in Paris in 2004, captures the spirit of our collaboration. In those days French academia had not yet fully embraced the online world, so she communicated from a super-slow connection in an internet cafe opposite her cheap hotel (which she was convinced was also a knocking shop). These suboptimal conditions account for the uncharacteristic typos; the extracts from my message to which she is replying are marked with >

Dear Eleanor,

> just checking that the latest version arrived chez toi.

Yes, and was put back in the post yesterday afternoon so should be with you any time. All looked good. I've added one or two tiny things - found the caption for Hilary's photos, for instance, but nothing that will change the structure.

> I thought I'd put the image of the first page between Peter's introduction and > Walter's article, as a full page image.

Peter thought that too, but I thought the manuscript made an eye-catching start if we put it first. I was also worried about the duplication of titles above the MS and above Walter's article, so wanted to separate them. Also, Peter's article is entitle[d] ‘Introduction’ without us yet knowing what it is an introduction to, unless we turn the page [and] look ahead. For all those reasons I decided on MS first, but if you think it looks better later and can sort out the headings, go ahead. But in that case perhaps it should be on the right hand side with Walter on the left (then we can take the heading away altogether from over the MS). So:

16-17 Peter

18 Walter first page

19 MS

20–26 Walter

I'm trying to imagine it but you can see it so do what you think looks best!

Bulletin 1 opens with one of Jackie's beautifully crafted editorials, giving the history of the Newsletter in much more detail than I have presented here, and generously acknowledging all the help she received in putting each issue together. As I typeset the piece, I emailed to her:

You always write ridiculously grateful lines in your editorial about my mechanical contribution to the NL; I'm tempted to replace them this time especially (but am always tempted) with a hymn to your patience, good humour and indefatigable retypings and rewritings. bravo!

Jackie's success with the Bulletin led to the sense that it might have a readership beyond the members of BSHM itself. In 2005 the Society began negotiations with Taylor & Francis to take over the publication of the journal and put its production and distribution on a professional footing. Once I had overseen the transition to T&F I was effectively out of an editorial job, and my involvement in the Bulletin diminished rapidly. Meanwhile Jackie, of course, continued at the editorial helm for a further seven years. She always worried that she wouldn't have enough content, or that it wouldn't be up to standard—but of course she made sure it always was. The fruits of her labours are online in the T&F archive (http://www.tandfonline.com/).

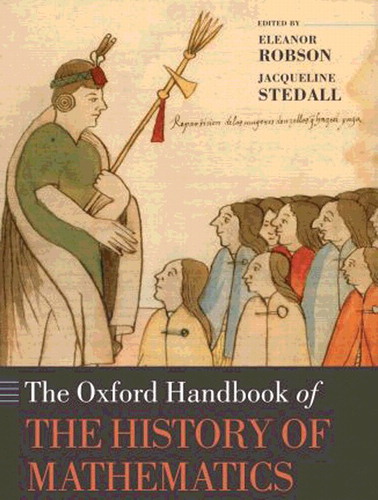

Meanwhile, we had enjoyed working together so much that we were soon looking for another excuse to do so. And thus, in early 2006, The Oxford Handbook of the History of Mathematics was conceived, thanks to OUP's then mathematics supremo, Alison Jones. We were too used to sitting round the table together—in my college office, in her kitchen, in my dining room, in Queen's Senior Common Room—drinking tea and egging each other on.

We were forgiving and ruthless in equal measure. Just as for the Bulletin, we looked for contributors who were not the usual suspects, the big names whom one would expect to find in an authoritative tome—and in fact several of these newcomers and outsiders had published with us in the Bulletin already. We knew that these people had interesting and useful things to say about the history of mathematics that had not yet been heard, and worked hard with them to show off their stories to best advantage.

In fact, we played with our thematic structure constantly. Here is our section outline from January 2007 (with three chapters envisaged for the opening and closing sections, five in the others):

What is Mathematics?

Mathematical Cultures

Transmission and Reception

Centres and Peripheries

Learning Mathematics

Making a Living

Mathematics in Practice

Number, Text, and Image

Historians and their Sources

Some of these themes are not so far from what we ended up with, a few weeks before the submission deadline—the outcome of a highly rigorous process whereby we wrote all the chapter titles on slips of paper and shuffled them around until they fell into more or less coherent groups:

Geographies and Cultures

Global

Regional

Local

People and Practices

Lives

Practices

Presentation

Interactions and Interpretations

Intellectual

Mathematical

Historical

The introduction to the Handbook, written in Jackie's kitchen, begins, ‘We hope that this book will not be what you expect’. We similarly chose the front cover image, from Gary Urton's chapter on the confrontation between Inka and Spanish imperial accounting practices in the sixteenth century, to both entrance and confound (). When reviews of the Handbook started to appear after its publication in 2009 we were delighted to discover that yes, it really wasn't what readers (or at least reviewers) had been expecting. We were thrilled when reviewers celebrated our challenge to the historical orthodoxy. Then again, complaints about the lack of Famous Mathematicians and Their Theorems, or long-dead historiographical spats, were particularly amusing to read, the more petulant the better. In fact, the FM and TT are there if you look for them, but not in their usual dominant role. (A quick search on Google Scholar will reveal the key reviews in each camp.)

The Handbook has proved a lasting success. It is still selling well, in hardback, paperback and ebook, and—thanks to Ken Saito—has just appeared in Japanese translation, sadly too late for Jackie to appreciate. Even though it's several years since we worked together, our friendship endured to the end. And although I miss her still—her warmth, her compassion, her humour, her stillness—there is the great consolation that our academic partnership produced work of lasting value. Quite apart from Jackie's own brilliance as a historian, she was unsurpassed at helping colleagues find their voices in print, and in stimulating students and researchers to think about the mathematics of the past in new and fruitful ways. The Babylonians believed that although physical immortality was impossible to achieve, one lived on in the memories of others, grateful for the good deeds one had done. In that case, Jackie's Babylonian afterlife will be glorious indeed.

Editor's note

Peter Neumann's obituary for Jackie Stedall, published in the Guardian, can be found at http://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/oct/24/jacqueline-stedall