ABSTRACT

At a time when the liberal international order is in crisis, several middle powers including Canada have taken the lead in pushing for the inclusion of women in peace operations under the banner of the 1325 agenda. This article assesses the implementation of the 1325 agenda in peacekeeping operations. We contend that the limited results of the agenda should primarily be attributed to the way liberal middle powers promoted it, rather than to opposition from conservative or less gendered-minded UN member states. We conclude by reflecting on the vulnerability of this agenda to changes in the dominant international ethos.

Introduction

At a time when the liberal international order is facing its most severe challenge to date, concerns have been expressed about the fate of UN Peacekeeping which, as Roland Paris’ contribution to this special issue notes, has entered into transition (Paris Citation2023). There are similar fears that the current period of ‘normative change and rupture’ (Dunton, Laurence, and Vlavonou Citation2023) threatens the Women Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, one of the most visible expressions of this liberal international order.

Adopted by the UN Security Council in October 2000, Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security was hailed as ‘a groundbreaking achievement in putting women's rights on the peace and security agenda of the UN’ (Tryggestad Citation2009, 539). Resolution 1325 sought to increase the representation and active participation of women in conflict prevention, management, resolution and in peacebuilding; it advocated the adoption of a gender perspective in planning and implementation of peace operations and peace negotiations, and it further underlined the need to pay attention to the protection and respect of women’s rights in armed conflict (Tryggestad Citation2009, 540–41). Subsequently, nine complementary resolutions, voted between 2000 and 2019, broadened the scope of UNSC Res 1325, adding new areas for action and pressing UN member-states on implementation.Footnote1 Overall, the WPS agenda aims to achieve gender equality and seeks the ‘radical reconfiguration of the gendered power dynamics that characterize our world and a properly global commitment to sustainable and positive peace’ (Kirby and Shepherd Citation2016, 373).

There is little disagreement over the fact that Resolution 1325 created a norm and that the WPS agenda has since become a fixture in the international arena. Adopted under Chapter VI, Resolution 1325 is noncoercive and intended to ‘influence behaviour (…) at both the international and national levels’ (Tryggestad Citation2009, 544). However, all three dimensions of Resolution 1325 did not proceed apace. We note critically slow progress on one specific dimension – the adoption of a gender perspective in planning and implementing peace operations and peace negotiations which has sometimes been identified as an international normative regime of its own (Carey Citation2001) and is the focus of this article.

Middle powers such as Canada, Sweden or Norway have taken the lead in propelling this part of the 1325 agenda. They have established or supported the establishment of several programs and initiatives and, in the process, have contributed to the creation of practices and to the diffusion of the normative regime embodied in Resolution 1325 and subsequent WPS resolutions. Reviews of these efforts published on the 20th anniversary of the passing of Resolution 1325 highlight constraints on their inability to push through a transformative agenda. Analysts have attributed the slowness and limited results to a backlash against the WPS agenda by some Security Council members (Salas Sanchez et al. Citation2020) as well as to overt and covert resistance to its implementation in a context of rising authoritarianism, populism, and nationalism (de Jonge Oudraat and Kuehnast Citation2020). In this article, we argue that the core weaknesses of the agenda are the result of unresolved internal tensions that, more than anything else, heighten the agenda’s vulnerability to changes in the international context.

Empirical evidence for the article draws in part upon the coauthors’ engagement in policy design and/or implementation. One of the coauthors’ conducted participant-observation in several UN gender trainings; she was also deployed in support of UN peacekeeping missions where she was able to observe and reflect upon the implementation of the UN’s WPS agenda. Analysis of Canadian initiatives to implement the WPS Agenda, especially the Elsie Initiative for Women in Peace Operations (Global Affairs Canada Citation2017), draws upon the practical experience in the Canadian government of the second coauthor who was namely involved in the design of the programming at the political level. These practical experiences played a key role in informing this article. Yet, the distance afforded by a return to the academic world provided both coauthors the space to reflect upon their practice and the perverse effects of some of the arguments used to advocate for the involvement of women in peace operations.Footnote2 The analysis also builds on a wealth of secondary sources as well as on official governmental and UN documents.

Resolution 1325 as normative entrepreneurship by middle powers

Resolution 1325 was adopted in a particular historical context. The campaign leading up to the resolution’s adoption was undoubtedly influenced by developments in international relations, among which scholars and observers note ‘a changed international security architecture, the changing nature of conflict, and the widening of the concept of security, together with the increasingly influential role of NGOs in international relations’ (Tryggestad Citation2009, 542–43). At the UN, not only had there been ongoing efforts to promote women’s rights – particularly under the leadership of the Commission on the Status of Women, but the first post-cold war decade had seen a profound change in the nature of peacekeeping operations, particularly as regards the expansion of peacekeeping mandates and the increasing importance of civilian mission components (Olsson Citation2000).

The Resolution was also testament to the presence at the UN of member states willing to exercise leadership in regard to the equal participation of women, the protection of their rights and the adoption of a gender perspective. Early in the campaign for Resolution 1325, Namibia, Bangladesh and Canada were among the most active member states. During Bangladesh's Security Council presidency in March 2000, the Security Council issued a statement on International Women's Day, linking peace with equality between men and women. The statement also reaffirmed that ‘equal access and full participation of women in power structures and their full involvement in all efforts for the prevention and resolution of conflicts are essential for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security’ (Press release SC/6816, 8 March Citation2000). The Nordic countries, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom would soon join in these efforts and in 2000, under a Canadian initiative, they established the Friends of WSP group, or Friends of 1325. Advocating for the implementation of Resolution 1325, the group grew to 31 member states by 2008. Today, it consists of 45 member states.

Taking advantage of the favourable international climate that followed the end of the cold war, members of the Friends of 1325 had begun promoting women’s rights in the realm of peace and security since the early to mid-1990s. Canada and the United Kingdom worked closely with the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO now Department of Peace Operations, DPO)Footnote3 in ‘developing training manuals in gender sensitivity for peacekeeping personnel’ (Tryggestad Citation2009, 547; Mackay Citation2003). The Nordic countries funded and provided research expertise and support to a DPKO study entitled Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in United Nations Multidimensional Peacekeeping Operations (Olsson Citation2000). Nordic countries also provided voluntary contributions to fund the position of a DPKO gender adviser. These countries have developed ‘good working relationships’ and ‘well established links’ with the NGO working group on WPS (Tryggestad Citation2009, 548), a network that according to two of its founding members, Felicity Hill and Maha Muna ‘began to appear informally at the 1998 meeting of the UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), which was examining the implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action chapter devoted to Women and Armed Conflict’ (Cohn, Kinsella, and Gibbings Citation2004, 131).

1325 and the UN Blue Helmets: Promoting normative change

Efforts to mainstream a gender perspective in UN operations led to the development of policy. As Dunton and her co-authors argue, peacekeeping ‘has always been a political tool of the UN’ and, in the post-Cold War era its missions are ‘implicit liberal symbols’ of the value of cooperation in global security governance (Dunton, Laurence, and Vlavonou Citation2023). Thus, peacekeeping policy has become a major discursive site of UN gender norms projection. A cursory review of the two main policy documents, the 2010 Gender Equality in UN Peacekeeping Operations and the 2018 Gender Responsive United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, underlines their intent to promote change, socialize relevant departments and units to modify their practices in line with the change sought and create opportunities for dialogue with UN member states to encourage similar change at the national level.

In 2010, the Department of Peacekeeping Operations issued its Gender Equality in UN Peacekeeping Operations policy with the stated purpose of ensuring the ‘equal participation of women, men, girls and boys in all peacekeeping activities’ (UN DPKO Citation2010, 2). Recognizing that Peacekeeping Operations are critical actors at the early stages of a post-conflict recovery process’, the document focused mostly on the way such operations could ‘advance gender equality and the empowerment of women in countries of deployment’ (UN DPKO Citation2010, 3).

The policy introduced the principle of gender balance which required ‘that the staffing profile at headquarters and in the missions reflect [the UN’s] institutional commitments to the equal representation of men and women at all post levels’ (UN DPKO Citation2010, 3). Thus, the policy directed the UN to collaborate and dialogue with troop and police contributing countries (TCCs/PCCs) to ‘advocate for the adoption of gender-sensitive policies which support the increased recruitment and deployment of uniformed women to peacekeeping’ (UN DPKO Citation2010, 6) and to recruit, retain and promote civilian personnel to advance gender balance among the personnel of DPKO and of the Department of Field Support (DFS).

The policy also directed all peacekeeping training and capacity-building to include a gender dimension. It required ‘all demographic and statistical data and information, including mission reporting, information presented to the Security Council and information posted on the DPKO/DFS website’ to be disaggregated by sex and age and requested reports to the Secretary General to ‘incorporate gender-specific information as appropriate in each thematic section, and also include whenever necessary/possible, a specific section on gender equality issues’ (UN DPKO Citation2010, 7). Lastly, it directed that all documentation and evaluation of peacekeeping practice should include an evaluation of the progress made in the implementation of the standards and benchmarks outlined therein.

In 2018, DPKO and DFS issued the Gender Equality in UN Peacekeeping Operations policy (UN DPO and DFS Citation2018) which provided the frame for efforts to adopt a gender perspective in planning and implementing peace operations. Alongside other policy documents issued that same year and the following year,Footnote4 the new policy put more emphasis on gender equality. The new policy defined its objectives as strengthening (1) managerial leadership and accountability, (2) systems and mechanisms for monitoring progress, (3) capacities and knowledge of all DPKO and DFS personnel on gender equality and WPS, and (4) engagements and partnerships within the UN and externally to achieve gender equality and WPS results (UN DPO and DFS Citation2018, 3).

In assessing the overall impact of efforts to implement and mainstream the WPS agenda in UN peace operations, we therefore distinguish between two categories of impacts. The first, the development of practices, focuses on the way the statement of principles and commitments outlined in Resolution 1325 and in DPKO/DPO policy guidelines translated into ‘the actual, mundane, daily procedures’ of the United Nations’ DPKO/DPO (Cohn, Kinsella, and Gibbings Citation2004, 134), specifically in efforts to collect gender data and in the appointment of gender components. The second, socialization, summarizes efforts exerted to diffuse the norm of gender mainstreaming in peacekeeping operations beyond an already-committed core group of member states. Socialization to gender equality and WPS has primarily taken the form of training workshops and of initiatives to increase the number of uniformed women.

Practices

According to Emmanuel Adler and Vincent Pouliot, practices are ‘socially meaningful patterns of action, which, in being performed more or less competently, simultaneously embody, act out, and possibly reify background knowledge and discourse in and on the material world’ (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011, 4). We identify two sets of practices, set out in the UN policy documents, that embody UN efforts to adopt a gender perspective in the planning and implementation of peace operations: the collection of gender data and the appointment of gender components.

Collecting gender data

The most obvious practice that observers can point to regarding the internalization of the norms of gender mainstreaming is the collection of gender-disaggregated data. To this effect, the reporting mechanisms of the Department of Peace Operations were changed early on to track the number of female police and military personnel in UN peace operations. In one of the earliest articles on the subject, Judith Stiehm noted that, prior to 1991, member states contributed less than two per cent women military personnel and an even lower percentage of civilian police (Citation2001, 40). Identifying Somalia as the country where the largest number of military women served, Stiehm notes that these were mostly US military personnel and that they represented 8 per cent of US troops, even though women constituted about 14 per cent of the US armed forces. Her research found that, at the same time, women constituted 32 per cent of civilian staff across UN peacekeeping missions but only 6 per cent of policy-level staff.

Writing in 2001, she noted that the systematic collection of gender-disaggregated field data showed that ‘While the military in some missions remains all male, in other missions female military personnel have increased to three per cent, and some missions have increased civilian women police to three and even five per cent. This includes the missions to East Timor and Kosovo, which are the first missions to have gender components’. Stiehm concludes that the data suggests that ‘New UN principles and policies, … , seem to have had some effect’ (Stiehm Citation2001, 40–41).

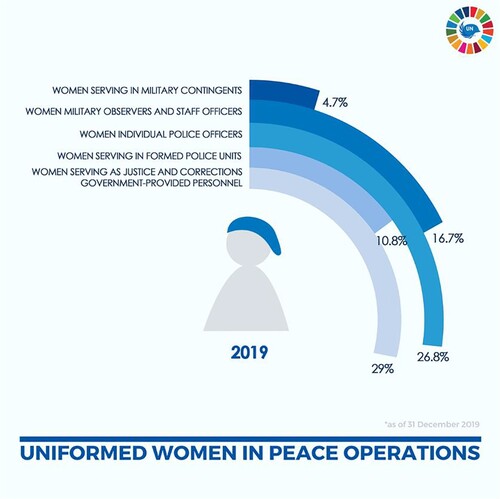

According to the United Nations, ‘in 1993, women made up 1 per cent of deployed uniformed personnel. In 2019, out of approximately 95,000 peacekeepers, women constitute 4.7 per cent of military contingents and 10.8 per cent of formed police units in UN Peacekeeping missions’ (United Nations DPO Citation2020). Recent data on uniformed women in peace operations suggests that most uniformed women are police officers (26.8 per cent) or justice and corrections personnel (29 per cent) (See ).

Figure 1. Uniformed Women in Peace Operations (2019). Source: UN Department of Peace Operations. 2020. “Our Peacekeepers.” Accessed May 23, 2022. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/our-peacekeepers.

It is worth noting here that there were few women serving in peacekeeping a decade before the passing of Resolution 1325; two decades on, the percentages have more than doubled but the overall number of women in peace operations remains low. Gender balance in peace operations depends on the national recruitment and retention policies of Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs), most of which currently hail from the Global South.Footnote5 Global North countries have higher percentages of women in uniform but they ‘do not readily supply their own troops opting instead to provide logistical and financial support’ (Davies and True Citation2019, 212). By so doing, Global North countries contribute to the low numbers of women in peace operations and put much of the onus of making missions gender equal unto Global South countries. As will be further discussed below, this also privileges a symbolic understanding of women’s inclusion that does not reflect the transformative initial ambitions of the WPS agenda. Indeed, countries such as Nepal or India deploy a significant number of female peacekeepers, sometimes in all-female units, but these same countries are reluctant to implement the WPS agenda at home (Basu Citation2016, 370).

Appointing gender components

The second practice that the UN has adopted is the appointment of ‘gender components’. The first DPKO gender adviser was a budgetary post financed by a voluntary contribution from Nordic states; the UN has since deployed a number of gender components to mainstream gender perspectives in the planning and implementation of peace operations. The UN defines gender mainstreaming as.

… the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making the concerns and experiences of women and men an integral dimension of design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated (Report of the Secretary-General A/57/731 Citation2003, 3).

Three kinds of gender components are at play here: gender advisers, gender units and gender focal points. Their role is to provide technical advice, guidance and support on ‘developing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating [a] mission’s strategy on mainstreaming gender as well as on the inclusion of gender perspectives into relevant mission policies, programmes and activities’ (Böhme Citation2008, 15). Gender components can also contribute to the development of tools, trainings and training materials for gender mainstreaming within a mission. Gender components are primarily intended to serve as a ‘catalyst for mainstreaming gender aspects into peace operations’; hence, their focus is predominantly inward (Böhme Citation2008, 15).

Socialization

In this article, socialization refers to a set of initiatives and mechanisms through which the Friends of 1325 and DPO have sought to affect change in UN member states and to bring these states to internalize and implement the WPS agenda in their domestic institutions. In the international relations literature on norms, socialization is a well-established mode of norm diffusion (Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink Citation1999) through which norm entrepreneurs persuade others to adopt a specific identity. We thus start from the premise that norms of gender equality tend to be associated with liberal democratic states. Given the focus of the paper, we pay specific attention to those initiatives intended to convince states to implement changes in favour of women’s inclusion in the police and armed forces as well as their deployment to peacekeeping missions. We single out two examples: gender training and increasing the number of uniformed women in peacekeeping.

Gender trainings

Gender trainings are by far the most ubiquitous way in which liberal middle power members of the Friends of 1325 have assisted the UN in its efforts to socialize member states and their representatives to the WPS agenda, particularly as relates to gender mainstreaming in the planning and implementation of peace operations. Mandated in the DPKO policy documents since 2010, training courses and workshops are either developed by the UN or funded by member states and designed/delivered collaboratively. Sweden and Norway are particularly active in this realm. The Swedish Folke Bernadotte Academy ‘offers a course for current or prospective civilian gender advisers or gender focal points in international peace operations, political missions, crisis-management missions, and peace and security organizations’ (Martin-Brûlé et al. Citation2020, 4). The Peace Research Institute of Oslo has joined forces with the Department of Peacebuilding and Political Affairs (DPPA) to train not only senior UN officials but also officials from member states and regional organizations who are being considered for senior appointments in mission settings. Although they vary both in terms of audience and format, most trainings have three interrelated objectives:

(1) to introduce and socialize participants to the normative framework behind the push for a gender perspective on peace and security; (2) to familiarize participants with the manner in which a ‘gender-based analysis plus’ changes their understanding of and approach to their area of thematic expertise (e.g. constitutional reform, peace negotiations, policing, justice, security sector reform, or protection of civilians in conflict); and (3) to derive a set of operational tools and principles for including women and integrating gender into their daily work. (Martin-Brûlé et al. Citation2020, 6)

Increasing the number of uniformed women in peacekeeping

According to a December 2021 infographic produced by DPO, ‘currently, only 7.8 per cent of all uniformed military, police and justice and corrections personnel in field missions are women’ (UN Department of Peace Operations Citation2020). While DPO acknowledged that considerable progress has been achieved since the adoption of the Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy, additional efforts are required to meet the targets set by the UN Security Council (2242) which called for doubling the number of women in uniformed components of peace operations by 2028.

The UN has used the data that it collects on women in uniform to target troop and police contributing states. Troop contributing countries (TCCs) are ranked based on the number of female peacekeepers they deploy. ‘Rankings are publicized in public information material, as well as during workshops and seminars attended by representatives of member states’. Audrey Reeves describes the practice as an effort to shape the conduct of would-be TCCs. Following Michel Foucault, she argues that governing practices ‘embed themselves in a web of knowledge and meanings that inform what is interpreted as the greater good and the means to achieve it’ (Reeves Citation2012, 353). The UN data is notably being used as part of the UN’s Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy 2018–2028 which seeks to ‘prioritize, where appropriate, TCCs who show improvements in female inclusion in peacekeeping force’ and if troop and police contributing countries do not meet gender targets and cannot prove they have tried to do so, ‘reallocate posts to T/PCCs willing and able to deploy more qualified female officers and who are meeting their individual targets’ (DPO 2018).

Friends of 1325 have also developed their own initiatives in this regard, of which Canada’s Elsie Initiative is the most important effort. Inspired by think-tank studiesFootnote6 which argued that solving the stalemate in the deployment of women peacekeepers was not simply a matter of voting on new UN Security Council resolutions or encouraging member states to comply with existing ones, it was instead squarely a matter of economic incentives, the Elsie initiative is the flagship of efforts to increase the number of women Blue Helmets and Blue Berets.

The impetus to launch the Elsie Initiative emerged at a time when Global Affairs Canada sought to contribute concretely to UN peacekeeping. Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy had just been launched (June 2017) and Canadian feminist civil society had mobilized to ensure that the government’s new feminist approach did not only sit within the realm of development assistance. The September 2017 Vancouver Peacekeeping Conference was also fast approaching and Canada, as the host, was expected to make several significant ‘smart’ peacekeeping pledges to respond to tangible needs expressed by DPKO.Footnote7

Consultations with experts and scholars made it clear that the deadlock in the deployment of women in missions was a complex issue. As a result, the concept evolved beyond financial incentives, to include support for an array of projects such as barrier assessment studies to diagnose country-specific challenges, technical assistance to specific UN missions and research programs to gather evidence. Considering that most T/PCCs come from the Global South, a contact group including Western and non-Western member states was established to consult and work together on the launch and development of the initiative.Footnote8 Canada also established specific bilateral partnerships with the Ghanaian Armed Forces, the Zambian Police Service and the Senegalese Armed Forces to support these countries in reforming their recruitment and training pipeline to ensure they had enough women in their security apparatuses who could then deploy to UN peacekeeping missions. The programme has now mostly been absorbed by the UN and evolves as a site of experimentation and innovation rather than as a permanent and well-established part of the UN system.

Penelope’s shroud – gender mainstreaming in peace operations as trick

While both the UN DPO and the Friends of 1325 have undoubtedly contributed to the diffusion of the norm, the development of practices and the socialization of other actors to the requirements of gender mainstreaming in peace operations, nevertheless, we argue that the implementation of gender mainstreaming in peace operations remains more of a trick than a treat (Tryggestad Citation2009). However, unlike analysts who place a significant portion of the blame on countries opposed to the WPS agenda (Salas Sanchez et al. Citation2020), we locate the obstacles to more significant norm diffusion in some of the choices that the norm entrepreneurs made in their pursuit of gender mainstreaming. More specifically, we argue that the UN Secretariat as well as some Friends of 1325 have privileged efficiency at the expense of equality in arguing the value of the WPS agenda. We further contend that, in so doing, they have essentialized women peacekeepers. Finally, we suggest that the decision to focus on women in uniform has favoured symbolic initiatives, and a focus on counting women, failing in the process to leverage other sources of transformative change. All in all, the promoters of the agenda find themselves in a position similar to Ulysse’s wife, Penelope, as she undid by night the shroud that she was knitting by day.

Pursuing efficiency at the expense of equality?

In making the case for gender integration in peace operations, Friends of 1325 and their allies in the UN Secretariat have regularly put forth arguments to the effect that women’s inclusion was, to quote Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the ‘smart thing to do’. Uniformed women are considered more suitable for peacekeeping which, some observers argue, is fundamentally different from waging war (DeGroot Citation2001). Female Blue Helmets have also been described as more likely to be able to establish contact with host societies (Karamé Citation2001). The integration of uniformed women has also been touted as a means to improve the behaviour of their male colleagues (Carey Citation2001). An increase in the representation of women in peace operations has variously been linked to ‘a decrease in the number of HIV/AIDS cases directly or indirectly linked to PKOs, a decline in the number of brothels around peacekeeping bases, and a reduction in the number of babies fathered and abandoned by peacekeepers after their mission comes to an end’ (Simić Citation2013, 1). Some researchers have presented quantitative evidence that suggests a decrease in the incidence of sexual exploitation and abuse in missions with a larger female presence (Karim and Beardsley Citation2016).

Not only do these arguments often build on or reinforce an essentialist view of women (more on this below), but to date, there is no proven connection between an increase in uniformed women peacekeepers and operational effectiveness, partly because the effects are hard to trace, isolate and measure, but also because they will likely not be observable in the short term. More importantly, such arguments undermine the norm of equality between men and women which was at the core of the UN’s own definition of gender mainstreaming. Even former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, while urging member states to contribute more female troops to peacekeeping missions, insisted that ‘the point is not to achieve gender parity for its own sake’, but ‘to draw on the unique and powerful contribution women can make’ (United Nations Secretary General Citation2009). As Audrey Reeves rightly notes, in arguing the case that women’s inclusion in peace operations would increase the efficiency of these operations, ‘feminist arguments find themselves co-opted in the reproduction of a discourse where women are portrayed as the instruments of political goals which are still mainly defined by and for men (Reeves Citation2012, 354). Emphasizing the ‘unique role’ women can play in peacekeeping can in fact cause a process of gender sidestreaming, a term that refers to the manner in which ‘the process of mainstreaming can be subverted, fail to challenge hegemonic masculinity, and perpetuate simplistic and traditional dichotomy’ (Newby and Sebag Citation2021, 149), thus marginalizing women’s roles and contributions. Indeed, by treating women as better suited for specific roles, conventional sex-based characterizations of women and men’s abilities are reproduced. To quote PM Trudeau again, the ‘smart thing to do’ ends up undermining the right thing to do.

Essentializing women peacekeepers

Arguments that link women’s inclusion in peace operations to increase efficiency typically build on an essentialist view of women’s qualities and skills. At a roundtable discussion organized by the Pearson Peacekeeping Center in 2009, UN gender advisers underlined women’s.

‘conciliatory nature’, resulting in a greater ‘ability to defuse potentially violent situations’; their communication skills, especially when engaging with local women; and their empathy, translating into a greater commitment to the inclusion of all voices and a stronger interest in issues of sexual violence, as well as in a ‘greater access to vulnerable communities’ in general and to women in particular (Reeves Citation2012, 353).

Furthermore, assuming that uniformed women deployed in missions can better relate to local communities relies on a reductionist view of womanhood as universal (Anania, Mendes, and Nagel Citation2020) that is not shaped by nationality, class, race or military identities. Relying on uniformed women to engage with local communities further dismisses the results of research which suggests that the inability to engage with local communities is more likely the result of UN peacekeeping security protocols that significantly constrain peacekeepers from engaging with local communities regardless of gender (Cassin and Zyla Citation2023).

Not only do such essentialist views of women undermine arguments for equality, but they also constrain the range of roles that uniformed women are expected to play and they negatively affect men’s perception and acceptance of the women in their ranks. In research documenting the experience of two Dutch peacekeeping units deployed in Bosnia, Liora Sion (Citation2008) found that some women who wished to serve in a combat role were ‘refused on the grounds of being a woman’. Others saw their roles change: ‘Instead of the functions they had been assigned to before the peacekeeping mission, they were given simple and unchallenging administrative work during the mission’ (Sion Citation2008, 575). Lindy Heinecken interviewed South African female soldiers deployed in Sudan and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Heinecken Citation2015). Her research showed that male soldiers were uncomfortable with the participation of women. Much as Sion who argues that male soldiers reject the participation of women and perceive them as endangering the missions’ prestige (Sion Citation2008, 561), she found that male soldiers complained about the women’s lack of aggressiveness and bravery while women felt the need to perform a militarized masculinity to offset some of the negative attitudes of their male colleagues (Heinecken Citation2015).

These essentialist depictions of women and of their roles in missions are often reproduced in the standard practices and initiatives intended to socialize UN member states to the principles of gender mainstreaming and the WPS agenda. This has proven particularly harmful to gender components, whether focal points, advisers or units. Instead of being leveraged, as intended, to help UN peace operations mainstream gender across the entire spectrum of mission activities, most gender components have been assigned a role as links to local women (and in many instances broader civil society). Visits to UN missions provide telling clues in this respect. More often than not, gender units are physically located at the back end of mission compounds. Gender advisers are not considered part of a mission’s senior management group and they are seldom asked for advice or feedback on operational and strategic planning. And a decade later, Böhme’s observation that, unlike their human rights counterparts, gender focal points are not systematically present in a mission’s regional offices (Citation2008) still holds.

Even flagship socialization efforts such as Canada’s Elsie Initiative are not protected against this essentialization. In a speech on the Elsie Initiative in December 2018 at the UN, Ana María Menéndez, the UN Secretary-General's Senior Adviser on Policy emphasized her support for the Elsie Initiative by arguing that ‘Female uniformed personnel are directly linked to our operational effectiveness in peacekeeping’ (United Nations Secretary General Citation2018). Speaking at an Elsie Initiative event at the UN, Ank Bijleveld, former Minister of Defense of the Netherlands argued that having more female peacekeepers will provide more intelligence (UN Women Citation2019). Even the initial press release from the 2017 Vancouver Peacekeeping Conference stated that this initiative was needed ‘to improve operational effectiveness’ (Office of the Prime Minister of Canada Citation2017). The risk of such arguments is that if there is no timely and incontrovertible evidence of the transformation of missions and increased effectiveness brought about by the inclusion of women, this operational ‘trick’ runs the risk of being abandoned. Transforming and improving the culture of peace operations takes time and requires reforms that are greater than adding women. It is not reasonable to expect a few uniformed women to single-handedly bear the burden of reducing sexual violence (perpetrated by men), improving intelligence gathering and building constructive relations with the community. Wilén (Citation2020) writes of this added burden for female peacekeepers who are asked to improve the conditions of the mission while also themselves facing the hostile conditions of these largely masculine missions. Such expectations set the inclusion of uniformed women for failure.

Interestingly, these arguments continue to be deployed despite the warning issued by a Canadian-funded baseline study conducted by the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance (Ghittoni, Lehouck, and Watson Citation2018) ahead of the launch of the Elsie Initiative. Indeed, the authors noted that ‘Critical Mass Theory would suggest, however, that the percentage of women currently serving, especially in military components, is far too low for women as a collective to have a significant impact on how peacekeeping operations function and hence the evidence base for operational effectiveness arguments is largely anecdotal’ (Ghittoni, Lehouck, and Watson Citation2018, 5). The study also debunked other popular myths about the integration of women, namely warning of the anecdotal nature of the evidence in support of uniformed women’s better relationships with local communities.Footnote9

Other research, supported by the Canadian government through the Elsie Initiative as well as by other liberal middle powers, cautions against common pitfalls related to policymaking in the realm of women in peace operations (Huhtanen Citation2022; Nagel, Fin, and Maenza Citation2021a,Citationb; Baldwin and Taylor Citation2020; Smith Citation2022). Drawing on case studies and interviews, their conclusions echo much of the recent literature on gender and peacekeeping (Karim and Beardsley Citation2013; Karim and Beardsley Citation2017; Wilén Citation2020) that emphasizes the need to transcend the trope that adding women without transforming the mission conditions and culture can lead to sustainable improvements (in terms of equality, performance, safety, etc). While this research has been taken on board in the refinement of the Elsie initiative and in the development of UN policies and practices regarding the inclusion of women in peace operations, this does not seem to have put an end to the transactional and numerical expectations decision-makers put on women peacekeepers. Despite these sophisticated studies, a pervasive simplistic and often stereotypical discourse has continued to be voiced in multiple national and international fora.

To sum up, preconceptions regarding women’s distinctive contributions to and roles in peacekeeping missions are challenging to uproot. Overcoming the entrenched division of labour in missions as well as the double-burden on female peacekeepers who are expected to exceed expectations while performing their duties in an environment of violence and harassment directed at women (Nagel, Fin, and Maenza Citation2021a) require multiple simultaneous transformations. In this regard, research by Nagel, Fin and Maenza stresses the need to emphasize the value of diversity rather than naively link women with operational effectiveness, as not only does this reinforce stereotypes, but more importantly, it can fuel resentment among male peacekeepers and undermine social cohesion (Nagel, Fin, and Maenza Citation2021a,b).

Symbolism over transformative potential

Lastly, the manner in which UN member states who are WPS norm entrepreneurs have decided to promote uniformed women’s inclusion privileges symbolic over transformative actions. This could arguably be said to illustrate the UN’s turn to pragmatic peacebuilding, defined as ‘the lowest common denominator’ (Dunton, Laurence, and Vlavonou Citation2023). As we discuss below, the piecemeal gender practices and policies represent an attempt to introduce a minimalistic liberal gender norm without ever enabling transformative feminist change.

In selecting to focus on increasing the number of uniformed women in military and police units, the Friends of WPS contributed (and continue to contribute) to conflating women’s inclusion with gender perspectives (Martin-Brûlé et al. Citation2020). This is a transversal problem in the promotion and pursuit of the WPS agenda at the UN. It is particularly reflected in the language of gender trainings, a large majority of which focus on women’s inclusion at the expense of a deeper engagement with the social construction of identities and power relations.

This has led some critics to describe the UN’s approach as ‘add women and stir’ (Dharmapuri Citation2011). As discussed earlier in this article, the numerical inclusion of women is not the solution to all the missions’ problems, especially to sexual violence. The UN needs to put the burden of preventing and addressing sexual violence on the men, who still represent the vast majority of peacekeepers (Anania, Mendes, and Nagel Citation2020). With the overwhelming expectations put on the women deployed in peacekeeping missions who still represent a small minority of all peacekeepers, we are more likely to set them up for failure by counting on them to instantly heal all the ills of the missions, without providing them with a safe environment or with the requisite power to effect change.

Similarly, in deciding to exclude the civilian component of missions from their advocacy efforts, the Friends of 1325 have also missed an opportunity. Indeed, research suggests that the positive impact of women’s inclusion tends to materialize when women make up about 30 per cent of a given institution, referred to as ‘critical mass theory’ (Kanter Citation1984, Dahlerup Citation1988).Footnote10 Given that the number of women in the civilian component of missions tends to be larger than the number of uniformed women, their full engagement could have acted as leverage to push the agenda forward. Effective gender mainstreaming in the security sector and including women in military roles also depends on successful gender mainstreaming in other sectors such as in ‘political and justice institutions and in conflict prevention, civilian policing, and peace agreement negotiations’ (Davies and True Citation2019, 24).

The overemphasis on counting women peacekeepers has also contributed to privileging symbolism in a different way. It has hidden another adjacent problem; the failure to collect and diffuse other types of gender-sensitive data essential to the implementation of the WPS agenda. Documenting the depth of this problem, Nagel, Fin, and Maenza (Citation2022, 443) conclude that the ‘paucity of gender-sensitive data has adversely impacted the WPS agenda in that the UN cannot measure the scope of the problem, resulting in policies that fail to serve all beneficiaries’. As such, not only has the Group of Friends of WPS have overemphasized the importance of counting women in missions, they also have failed to advocate for the collection of other deeply relevant gender data. Indeed, ‘understanding the gendered dimensions of conflict is not an optional luxury’ (Nagel, Fin, and Maenza Citation2022, 450). This unilateral focus on sending and counting women to missions curtails the original transformative ambitions of the agenda.

In this regard, the Elsie Initiative, much as it may represent a call for action and a genuine attempt at improving gender equality in peace operations, shares some of the same weaknesses as other UN practices and efforts. While it is too early to pass a definitive judgment on the results of this five-year pilot programme, the Elsie Initiative has focused the attention of several countries at the UN on advancing the WPS agenda, but it has not presented gender transformative solutions. Like others, it remains too focused on the numerical inclusion of women rather than on the transformation of gender norms in domestic security institutions and UN peacekeeping missions. It also leaves out women in civilian roles and, as discussed earlier, it also sometimes falls into the trap of essentializing women.

Conclusion: Will the future of peacekeeping be female?

This article began with a question about the vulnerability of the WPS agenda in peacekeeping to the current backlash against the liberal international order. We return to this question in the conclusion. Transnational feminist activists have argued that progress on gender equality in international institutions seems to have ‘hit a wall’ (Goetz Citation2020, 162). This tipping point in gender norm development and diffusion is generally attributed to a global backlash against gender normative agendas such as WPS. Anne Marie Goetz describes this anti-gender movement as initially led by the Vatican but gradually consolidating into ‘a curious coalition that now includes authoritarian and right-wing populist regimes and bridges significant differences of religious belief, regime type, and ideology’ (Citation2020, 160). A hostile environment against the WPS agenda has also been documented in national contexts (O’Sullivan and Krulišová Citation2020; Trojanowska Citation2021).

At the UN, the NGO working group on WPS has also noted a similar backlash. The working group has notably documented Russia’s and China’s lack of support for the WPS agenda, with Russia even questioning whether this should fall within the purview of the Security Council’s mandate (NGO Working Group on WPS Citation2020). In October 2020, during its presidency of the Security Council, Russia unsuccessfully attempted to pass a draft resolution (S/2020/1054) to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the landmark UN Security Council Resolution 1325 which, according to critics, attempted to ‘downgrade UN commitment towards women’s roles and rights in peace and security efforts’ (Salas Sanchez et al. Citation2020). Further, Russian representatives have also repeatedly used essentialist arguments when discussing women’s contributions to peace and security.

In 2000, Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s then-ambassador to the UN, noted that ‘“women”, “peace” and “security” combine harmoniously, because this harmony is predetermined by nature’. Twenty years later, [Russian Permanent Representative Vassily] Nebenzia linked women’s rights to the family, concluding the 29 October debate with the statement ‘the family is of special value, we must ensure its protection’ (Salas Sanchez et al. Citation2020).

By deploying arguments that link the inclusion of uniformed women to the increased operational efficiency of missions, the UN and the members of the Group of Friends of WPS have made women’s participation in peacekeeping conditional on being able to assess and demonstrate this efficiency. By essentializing the roles women play as peacekeepers, they have constrained the range of contributions women can make to peacekeeping. By focusing on the highly visible symbolism of increased numbers of uniformed women, they have watered down the notion of gender mainstreaming and reduced it to women’s inclusion. Taken together, the choices that the UN DPO and the Group of Friends of WPS have made in implementing the agenda have contributed to the slow progress decried by activists and documented by researchers. This heightens the vulnerability of any limited gains achieved to this date to changes in the international order.

In conclusion, it is important for countries that worry about challenges to the liberal international order to remember that UN Security Council Resolution 1325 was not the result of incremental negotiated change sweetened with financial incentives. It was the result of a grassroot mobilization that aimed to empower women and revolutionize gender norms (Confortini Citation2012; Thomson Citation2019). Unlike current efforts to mainstream gender in peace operations, these efforts were squarely based on a discourse of rights and on the moral imperative of gender equality, not on arguments about smart choices and increased efficiency. The mobilization that resulted in the passing of UNSC Resolution 1325 was anchored in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which states that ‘[e]veryone has the right of equal access to public service in his country’ (United Nations, cited in Ghittoni, Lehouck, and Watson Citation2018, 18). It was also anchored in specific experiences such as Namibia’s. Namibia, which played a key role in bringing about UNSC Res. 1325, emphasized women’s fight for independence and their involvement in the United Nations Transitional Group (UNTAG), the peacekeeping mission established to supervise elections and oversee implementation of the peace process (1989-1990).Footnote11

UNSCR 1325 and the concept of gender balancing were about women’s rights and gender equality; they devolved into a functionalist debate through practices at the UN (Karim and Beardsley Citation2013, 465). As Kirby and Shepherd have forcefully argued, a ‘more compromised programme has been crucial to the progress of WPS to date, and yet that progress can only be measured against an agenda for peace and security which demands transformations beyond the power of internal strategy’ (Kirby and Shepherd Citation2016, 392). Reconnecting DPO’s practices and its socialization efforts with the spirit that animated the passing of UNSC Res. 1325 is necessary to truly transform peace operations and make UN peacekeeping missions gender equal. To protect the gains that have been made to date, the UN DPO and the Group of Friends of WPS would be well-advised to focus more squarely on the right thing to do.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Kim Beaulieu for her research assistance and Liam Richardson for his editorial support as part of the revision process of this article. They would also like to thank the guest editors of the journal for their work putting this important issue together as well as the anonymous reviewers for their constructive revisions and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marie-Joelle Zahar

Marie-Joëlle Zahar is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Research Network on Peace Operations at the Université de Montréal.

Laurence Deschamps-Laporte

Laurence Deschamps-Laporte is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Université de Montréal.

Notes

1 Resolution 1820 (2008) focused on recognizing sexual violence as a weapon of war and called for prevention and response to sexual violence. Resolution 1888 (2009) reiterated that sexual violence exacerbates conflict and prevents peace and security. It called for responses from UN leadership to this issue and for the deployment of experts. Resolution 1889 (2009) focused on women’s participation in post-conflict peace building and on the development of WPS indicators. Resolution 1960 (2010) stressed the need for strong political measures that can bring an end to sexual violence. Resolution 2106 (2013) deepened the operationalization of measures concerning conflict-related sexual violence while Resolution 2122 (2013) called for a holistic approach to including women and building sustainable peace. Resolution 2242 (2015) pressed for new areas of integration of the WPS agenda such countering violent extremism. It highlighted the role of civil society and its importance in all country-based work. Finally, in 2019, two more resolutions were passed (2467 and 2493). The first emphasized the need for policies and justice mechanisms for survivors of sexual violence while the second marked the 20th anniversary of Resolution 1325 and demanded reinforced measures on all areas of action and increased funding. Most importantly, it emphasized the need to promote all the rights of women (civil, political, economic).

2 Indeed, we believe that policy-makers can fall into the trap of unintentionally perpetuating stereotypes and focusing on marginal improvements. This can happen as a result of unintended consequences of specific programming or because the lack of momentum for comprehensive gender transformation makes marginal gains attractive.

3 In this article, we will use the acronyms DPKO and DPO according to proper chronological periodization. DPKO will refer to the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (1992-2018); DPO will refer to the Department of Peace Operations (2018 - ).

4 These include the Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy 2018–2028 (UN DPO and DFS Citation2018), the United Nations Field Missions: Preventing and Responding to Conflict-Related Sexual Violence (2019).

5 In 2022, the top TCCs globally were Bangladesh, India, Rwanda, Nepal, Pakistan and Egypt (United Nations Peacekeeping Citation2022).

6 Charles Kenny (Citation2016) in a paper for The Centre for Global Development suggested that significantly increasing the participation of women in peace operations could cost as little as $77 million USD per year. This paper purported that direct financial incentives needed to be urgently directed at troop-deploying countries to ensure that they deploy more women to UN peacekeeping missions.

7 DPKO had indicated that Canadian support would be sought for MINUSMA and the United Nations Regional Service Centre in Entebbe; in parallel, Canada began to work on a specific gender-oriented pledge to announce in Vancouver.

8 Members of the Contact Group include Argentina, Canada, France, Ghana, The Netherlands, Norway, Senegal, South Africa, South Korea, Sweden, The United-Kingdom, Uruguay, and Zambia.

9 Authors of the baseline study identified 14 barriers to the deployment of uniformed women in peace operations, distributed in six main categories: ‘(1) equal access to opportunities, (2) deployment criteria, (3) the working environment, (4) family constraints, (5) equal treatment during deployment, and (6) career-advancement opportunities’ (2018, 2). Most of these barriers and the solutions for overcoming them are context-specific and can only be identified when studying specific missions.

10 The research on ‘critical mass theory’ mostly stems from studies of legislative bodies and on the empirical relationship between the representation of women and the passing of ‘women-friendly legislation’. Some of the empirical evidence has been misconstrued however and feminist scholars call for an investigation of the multiple forms the relationship between women’s descriptive and substantive representation can take. (Childs and Krook 2008)

11 Women made up 40% of what was referred to as the professional service and 50% of overall staff in UNTAG (Weiss Citation2021, 141). Women described their experience as empowering and exhilarating in UNTAG. Current Namibian Ambassador to the US and High Commissioner to Canada Monica Ndiliawike Nashandi described her experience in UNTAG as being a ‘freedom fighter alongside my fellow women combatants who served at the frontline’ (Weiss Citation2021, 140).

References

- Adler, Emanuel, and Vincent Pouliot. 2011. “International Practices.” International Theory 3 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1017/S175297191000031X.

- Anania, Jessica, Angelina Mendes, and Robert U. Nagel. 2020. Preventing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by Male Peacekeepers. Washington: US Institute of Peace.

- Baldwin, Gretchen, and Sarah Taylor. 2020. Uniformed Women in Peace Operations: Challenging Assumptions and Transforming Approaches. International Peace Institute. June 23.

- Basu, Soumita. 2016. “The Global South Writes 1325 (Too).” International Political Science Review 37 (3): 362–374. doi:10.1177/0192512116642616.

- Boulding, Elise. 1995. “Feminist Inventions in The Art of Peacemaking: A Century Overview.” Peace & Change 20: 408–438. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0130.1995.tb00245.x.

- Böhme, Jeanette. 2008. Human Rights and Gender Components of UN and EU Peace Operations: Putting Human Rights and Gender Mandates Into Practice. (Studie / Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte). Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317017

- Burguieres, Mary K. 1990. “Feminist Approaches to Peace: Another Step for Peace Studies.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 19 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1177/03058298900190010201.

- Carey, Henry F. 2001. “Women and Peace and Security': The Politics of Implementing Gender Sensitivity Norms in Peacekeeping.” In In Women and International Peacekeeping, edited by Louise Olsson, and Torunn Tryggestad. London: Routledge.

- Cassin, Katelyn, and Benjamin Zyla. 2023. “UN Reforms for an Era of Pragmatic Peacekeeping.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 17 (3): 294–312.

- Cohn, Carol, Helen Kinsella, and Sheri Gibbings. 2004. “Women, Peace and Security Resolution 1325.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 6 (1): 130–140. doi:10.1080/1461674032000165969.

- Confortini, Catia Cecilia. 2012. Intelligent Compassion: Feminist Critical Methodology in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dahlerup, Drude. 1988. “From a Small to a Large Minority: Women in Scandinavian Politics.” Scandinavian Political Studies 11 (4): 275–298. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1988.tb00372.x.

- Davies, Sarah E., and Jacquie True. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Women, Peace, and Security. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Jonge Oudraat, Chantal, and Kathleen Kuehnast. 2020. The Women, Peace and Security Agenda at 20: Setbacks, Progress, and the Way Forward. Available at https://www.justsecurity.org/73120/the-women-peace-and-security-agenda-at-20-setbacks-progress-and-the-way-forward/.

- DeGroot, Gerard J. 2001. “A few Good Women: Gender Stereotypes, the Military and Peacekeeping.” International Peacekeeping 8 (2): 23–38. doi:10.1080/13533310108413893.

- Dharmapuri, Sahana. 2011. “Just Add Women and Stir?” Parameters 41 (1): 56–70.

- Dunton, Caroline, Marion Laurence, and Gino Vlavonou. 2023. “Pragmatic Peacekeeping in a Multipolar Era: Liberal Norms, Practices and the Future of UN Peace Operations.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 17 (3): 215–234.

- Ghittoni, Marta, Léa Lehouck, and Callum Watson. 2018. Elsie Initiative for Women in Peace Operations Baseline Study. Geneva: Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance(DCAF). https://dcaf.ch/sites/default/files/publications/documents/Elsie_Baseline_Report_2018.pdf.

- Global Affairs Canada. 2017. Elsie Initiative for Women in Peace Operations. Ottawa: GlobalAffairsCanada. https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/gender_equality-egalite_des_genres/elsie_initiative-initiative_elsie.aspx?lang=eng.

- Goetz, Anne Marie. 2020. “The New Competition in Multilateral Norm-Setting: Transnational Feminists & the Illiberal Backlash.” Daedalus 149 (1): 160–179. doi:10.1162/daed_a_01780.

- Heinecken, Lindy. 2015. “Are Women ‘Really’ Making a Unique Contribution to Peacekeeping?” Journal of International Peacekeeping 19 (3-4): 227–248. doi:10.1163/18754112-01904002.

- Huhtanen, Heather. 2022. Fit-for-the-Future Peace Operations: Advancing Gender Equality to Achieve Long-Term and Sustainable Peace. Global MOWIP Report. Geneva: DCAF. https://www.dcaf.ch/global-mowip-report-2022.

- Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. 1984. “Some Effects of Proportions on Group Life.” In In: The Gender Gap in Psychotherapy: Social Realities and Psychological Processes, edited by Patricia Perri Rieker, and Elaine (Hilberman) Carmen, 53–78. MA: Springer US.

- Kaplan, Laura Duhan. 1994. “Woman as Caretaker: An Archetype That Supports Patriarchal Militarism.” Hypatia 9 (2): 123–133. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1994.tb00436.x.

- Karamé, Kari H. 2001. “Military Women in Peace Operations: Experiences of the Norwegian Battalion in UNIFIL 1978–98.” International Peacekeeping 8 (2): 85–96. doi:10.1080/13533310108413897.

- Karim, Sabrina, and Kyle Beardsley. 2013. “Female Peacekeepers and Gender Balancing: Token Gestures or Informed Policymaking?” International Interactions 39 (4): 461–488. doi:10.1080/03050629.2013.805131.

- Karim, Sabrina, and Kyle Beardsley. 2016. “Explaining Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in Peacekeeping Missions: The Role of Female Peacekeepers and Gender Equality in Contributing Countries.” Journal of Peace Research 53 (1): 100–115. doi:10.1177/0022343315615506.

- Karim, Sabrina, and Kyle Beardsley. 2017. Women, Peace, and Security in Post-Conflict States. London: Oxford University Press.

- Kenny, Charles. 2016. Using Financial Incentives to Increase the Number of Women in UN Peacekeeping. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/using-financial-incentives-increase-number-women-un-peacekeeping.

- Kirby, Paul, and Laura Shepherd. 2016. “The Futures Past of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.” International Affairs 92 (2): 373–392. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12549.

- Mackay, Angela. 2003. “Training the Uniforms: Gender and Peacekeeping Operations.” Development in Practice 13: 217–223. doi:10.1080/09614520302939.

- Martin-Brûlé, Sarah-Myriam, Stefanie Von-Hlatky, Savita Pawnday, and Marie-Joëlle Zahar. 2020. Gender Trainings in International Peace and Security: Toward a More Effective Approach. New York: International Peace Institute. https://www.ipinst.org/2020/07/gender-trainings-in-international-peace-and-security.

- Nagel, Robert U., Kate Fin, and Julia Maenza. 2021a. Gendered Impacts on Operational Effectiveness of UN Peace Operations. Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security.

- Nagel, Robert, Kate Fin, and Julia Maenza. 2021b. Peacekeeping Operations and Gender: Policies for Improvement. Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security.

- Nagel, Robert, Kate Fin, and Julia Maenza. 2022. “You Cannot Improve What You Do Not Measure – The Gendered Dimensions of UN PKO Data.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 16 (4): 434–454.

- Newby, Vanessa F, and Clotilde Sebag. 2021. “Gender Sidestreaming? Analysing Gender Mainstreaming in National Militaries and International Peacekeeping.” European Journal of International Security 6 (2): 148–170. doi:10.1017/eis.2020.20.

- NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security. 2020. Security Council Members Unite to Protect the Women, Peace and Security Agenda on its 20th Anniversary. New York: NGO Working Group Office. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.womenpeacesecurity.org/blog-unsc-protect-wps-agenda-20th-anniversary/

- Office of the Prime Minister of Canada. 2017. The Elsie Initiative for Women in Peace Operations.AccessedMay23,2022. https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/backgrounders/2017/11/15/elsie-initiative-women-peace-operations.

- Olsson, Louise. 2000. “Mainstreaming Gender in Multidimensional Peacekeeping: A Field Perspective.” International Peacekeeping 7 (3): 1–16. doi:10.1080/13533310008413846.

- O’Sullivan, Míla, and Kateřina Krulišová. 2020. ““This Agenda Will Never be Politically Popular”: Central Europe’s Anti-Gender Mobilization and the Czech Women, Peace and Security Agenda.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 22 (4): 526–549. doi:10.1080/14616742.2020.1796519.

- Paris, Roland. 2023. “The Past, Present, and Uncertain Future of Collective Conflict Management.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 17 (3): 235–257.

- Reeves, Audrey. 2012. “Feminist Knowledge and Emerging Governmentality in UN Peacekeeping.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 14 (3): 348–369. doi:10.1080/14616742.2012.659853.

- Risse, Thomas, Steven Ropp, and Kathryn Sikkink1999. The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Salas Sanchez, Patricia, Nuri Widiastuti Veronika, Irine Hiraswari Gayatri, and Jacqui True. 2020. “A Backlash Against the Women, Peace and Security Agenda?” The Interpreter. 5 November. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/backlash-against-womenpeace-and-security-agenda. Accessed 15 May 2021.

- Salla, Michael. 2001. “Women & War, Men & Pacifism.” In In Gender, Peace and Conflict, edited by Inger Skjelsbæk, and Dan Smith, 68–79. London: Sage Publications.

- Simić, Olivera. 2010. “Does the Presence of Women Really Matter? Towards Combating Male Sexual Violence in Peacekeeping Operations.” International Peacekeeping 17 (2): 188–199. doi:10.1080/13533311003625084.

- Simić, Olivera. 2013. Moving Beyond The Numbers: Integrating Women Into Peacekeeping Operations. NOREF Policy Brief. Oslo: NOREF, February.

- Sion, Liora. 2008. “Peacekeeping and the Gender Regime.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 37 (5): 561–585. doi:10.1177/0891241607309988.

- Smith, Sarah. 2022. Gender-Responsive Leadership in UN Peace Operations: The Path to a Transformative Approach? International Peace Institute. February 16.

- Stiehm, Judith Hicks. 2001. “Women, Peacekeeping and Peacemaking: Gender Balance and Mainstreaming.” International Peacekeeping 8 (2): 39–48. doi:10.1080/13533310108413894.

- Thomson, Jennifer. 2019. “The Women, Peace, and Security Agenda and Feminist Institutionalism: A Research Agenda.” International Studies Review 21 (4): 598–613. doi:10.1093/isr/viy052.

- Trojanowska, Barbara K. 2021. “Women’s Rights Facing Hypermasculinist Leadership: Implementing the Women, Peace and Security Agenda Under a Populist-Nationalist Regime.” Feminist Legal Studies 29 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1007/s10691-021-09464-4.

- Tryggestad, Torunn L. 2009. “Trick or Treat? The UN and Implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 15 (4): 539–557. doi:10.1163/19426720-01504011.

- UN Department of Peace Operations. 2020. “Our Peacekeepers.” Accessed May 23, 2022. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/our-peacekeepers.

- UN Department of Peace Operations. 2019. Uniformed Women in Peace Operations. Accessed 22 May 2022. https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/uniformed_women_in_pk_2022_stats_updated.pdf.

- UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations and Department of Field Support. 2010. Gender Equality in UN Peacekeeping Operations. Accessed May 22, 2022. https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/peacekeeping/en/gender_directive_2010.pdf.

- UN Department of Peace Operations and Department of Field Support. 2018. Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy 2018-2028. New York: United Nations DPO and DFS. https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/uniformed-gender-parity-2018-2028.pdf.

- UN Security Council. 8 March 2000. Press release SC/6816: Peace Inextricably Linked with Equality Between Women and Men says Security Council, in International Women’s Day Statement.” Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.un.org/press/en/2000/20000308.sc6816.doc.html.

- UN Women. 2019. “The Elsie Initiative Fund launched to increase uniformed women in UN peacekeeping.” Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2019/3/news-the-elsie-initiative-fund-launched-to-increase-uniformed-women-in-un-peacekeeping.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2003. Gender Mainstreaming in Peacekeeping Activities: Report of the Secretary-General A/57/731. New York: United Nations. 13 February.

- United Nations Peacekeeping. 2022. “Our Peacekeepers.” Accessed March 2, 2022. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/our-peacekeepers.

- United Nations Secretary General. 2009. “Secretary-General’s Message on the International Day of Peacekeepers.” https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2009-05-29/secretary-generals-message-international-day-peacekeepers.

- United Nations Secretary General. 2018. “Remarks to the Elsie Initiative for Women in Peace Operations.” https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/remarks-sg-team/2018-09-26/remarks-elsie-initiative-women-peace-operations-breaking.

- Warren, Karen J., and Duane L. Cady. 1994. “Feminism and Peace: Seeing Connections.” Hypatia 9 (2): 4–20. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1994.tb00430.x.

- Weiss, Cornelia. 2021. “Creating UNSCR 1325: Women Who Served as Initiators, Drafters, and Strategists.” In Women and the UN, edited by Rebecca Adami, and Daniel Plesch, 139–160. London: Routledge.

- Wilén, Nina. 2020. “Female Peacekeepers’ Added Burden.” International Affairs 96 (6): 1585–1602. doi:10.1093/ia/iiaa132.