ABSTRACT

This paper explores the engagement and attitudes of students in a UK school learning about the Holocaust, with a focus on refugee students. This paper explores students’ behavioral, cognitive and emotional engagement with the subject, with a focus on the students’ experiences. Findings revealed an enthusiasm and understanding from most students, but particularly refugee students. The culture in the classroom was also studied, showing that there were pockets of antisemitism in its contemporary form present in the classroom, impacting student learning. This paper explores the links between these findings, the implications and suggestions of what this means for current practice.

Introduction

The following paper is based on my thesis, ‘refugee engagement with Holocaust education: an exploration.’Footnote1 I myself am primarily a Secondary school History teacher, and the research and findings are presented with other similar teachers in mind. This paper will explore the aims of my study, present the data and continue to the findings and discussions in order to present my recommendations for teaching the Holocaust in diverse classrooms with refugee heritage students.

The majority of my teaching has taken place in diverse inner-city London schools teaching students aged 11–18. I became interested in how refugee students learn, when in the same classes as white British students through all my work with and training for the Special Educational Needs Department (SEND) and English as an Additional Language (EAL) Department, in a literacy role I held. Working with diverse students, within the History Department we worked tirelessly to ensure the curriculum we provided was as diverse and inclusive as we could. This work also led to the teaching of controversial and sensitive issues, the Holocaust being one of these. I became aware of the importance of addressing misconceptions, the importance of teaching the bigger concepts of the Holocaust and the importance of checking students’ understanding and learning. I then began to question the engagement of students with emotionally or philosophically difficult topics. Consequently, I decided to embark on a PhD as a means of developing my professional practice in these areas and inform the practice of others.

I spent some time exploring the research question, which I found complicated and difficult to articulate clearly in advance of the research process.Footnote2 It came about through a study of the literature and my own interests and professional experiences. To begin with, my interests were to do with students’ academic and emotional engagement with the Holocaust and the role their backgrounds and the teachers play in this. I was also interested in the preconceptions that students had from home or lived experiences and the ways in which they engaged with the Holocaust before learning about it at secondary school. This led me to focus on the preconceptions of students and an understanding of how these preconceptions were formed as well as a focus on the engagement of students in the classroom with the Holocaust, using their understanding of its contemporary relevance as a marker for engagement. I formulated the research title of ‘Refugee Engagement with Holocaust Education – an Exploration,’ data on the above will be presented below.

The Holocaust in English secondary schools

The ethnic, socio-economic, and religious backgrounds of schools have changed over the last 50 years particularly in inner-city schools. The turbulent geopolitics of the world and increased number of refugee and asylum-seeking students in schools has led to new guidance and frameworks for schools to followFootnote3 to ensure good practice in teaching and learning for all staff and all students. By the time these students reach History lessons in Secondary School, where they learn about the Holocaust as the only prescribed topic in the English National Curriculum at Key Stage Three, for 11–14-year olds, their backgrounds and lived experiences influence their preconceptions, misconceptions, knowledge and understanding on the topic. This will be true for the white working-class student to the newly arrived asylum-seeking Syrian student, to the Black Caribbean boys and second or third generation migrant students.

At Secondary school students have the opportunity to engage with learning about the Holocaust in different ways in different schools. Through History (compulsory), Religious Education, Personal Social and Health Education (PSHE) and extra-curricular opportunities like hearing from Holocaust survivors or visiting Auschwitz. Some schools study the Holocaust further at GCSE or A Level, but all students will come across it at some point in their schooling.

The Holocaust has been a longstanding topic in the curriculum, through each of its reforms since the introduction of the National Curriculum.Footnote4 Since 2014 there have been no changes to the National Curriculum, however, there have been reforms within the education system that have influenced what is taught and how. The important thing to note is the Holocaust has in some way been included as a compulsory content to be taught in all of England’s state-maintained secondary schools since the introduction of the National Curriculum in 1991. As Pettigrew posits, five Prime Ministers and thirteen Secretaries of State for Education have overseen many curricular changes and restructures, but ‘in its present iteration the symbolic significance of the Holocaust has never been more profound.’Footnote5

Refugee education

The Refugee CouncilFootnote6 explains that education is compulsory for all children from 5 to 16 including children seeking asylum. This is not always the case. There are many barriers to education for refugee students, including trauma of experience and experiences on arrival.Footnote7 Additionally, the refugee student well-beingFootnote8 and health, poverty and housing issues faced by refugees impacts the lives of children in and out of school.Footnote9 Asylum seeking children may attend mainstream schools local to where they live under the same conditions, formally, as other children in their area. However, as the Asylum in Europe website explains, all these barriers affect refugee students’ access to education. It has been found, however, that the best form of help for students’ emotional well-being was to attend school.Footnote10 Even if it was challenging for those students that speak little English on arrival, it provides a ‘normalising’ experience. This combats other situations where educational experiences created anxieties and stress for young people.

Roy and RoxasFootnote11 note that many teachers feel like they do not have the knowledge or training required to respond to the academic and social needs of refugee students, nor the professional experience. Many schools do not consider the young peoples’ previous learning and can also fail to recognize other skills, capabilities and subjugated knowledges, which refugee students bring to the formal learning environment.Footnote12 This can lead to unreasonably low expectationsFootnote13 and inappropriate pedagogies. Jones and RutterFootnote14 argued that resources for refugee education were inadequate, and that refugee children were often seen as ‘problems’ – rather than having the potential to bring positive elements into the classroom, and evidence suggests this is still the case.Footnote15

There has been a renewed focus in the teaching of ‘Fundamental British Values.’Footnote16 Since 2006, the level of threat of international terror in the UK has been rated at severe or higher. This has led to a focus on another issue: islamophobia in the UK, and how that is linked to refugees and migration. In July 2011 the ‘Prevent Strategy’ was introduced by Home Secretary Theresa May.Footnote17 Within the strategy a number of key terms are defined, such as ‘extremist’ as having ‘vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs.’Footnote18 They publicized the best way to deal with radicalization and non-violent extremism as being through schools, building a sense of ‘British Values’ and developing a sense of belonging to this country and support of these core values. After the UK’s decision in 2016 to leave the European Union, there has been another dimension to these discussions added. Brexit caused an increase in hate crimes and attacks against ethnic minorities by 41% after the vote in June 2016, and there have followed political conversations and committees discussing stricter laws on immigration and rights to remain because of the apparent threat. Arguably, this might make it more difficult for schools to teach about equality, kindness, and British values in the heightened climate of hate, anxiety and highlighting differences, compounded by more recent terrorist events such as those in Manchester (2017) and London (2017), which heightened Islamophobia.Footnote19 Making Holocaust education, teaching refugees and teaching refugee students about the Holocaust all the more complicated.

Aims of the study

The aims of the study were to explore the views held by students towards learning about the Holocaust and see whether these views were similar across all students, or just within the refugee community. This came about from an experience I had in the classroom whilst teaching the Holocaust to a class of Year 9 (age 13–14) students. In one of their early lessons, looking at antisemitism over time, the boisterous and ethnically diverse class were having several interesting discussions. This led to a very in-depth and political conversation between me and a young boy. To sum up the argument, his argument was that he wasn’t interested in learning about this topic as ‘it had been made bigger by the government and had become too tangled a situation,’ and he was interested in ‘learning about the plight of the Palestinians.’ He told me that he hated ‘all Jews’ as they were the reason that he had to be in school in England and so ‘why should I learn about a Jewish topic in History when we don’t look at any other religions.’ This conversation was dealt with at the time, through meaningful discussion that involved the whole class, and I found out that this student was a Palestinian refugee. It was from this, and the culmination of views within that classroom, that my attention was drawn to the necessity for teachers to comprehend the ways in which a student’s personal, social, and cultural experiences influenced their views and understanding of the world. Refugee students were the motivation of the study.

The school that I compiled the data from was a school that I had been working at as a History and Politics teacher. The school had been supportive of my work as a Holocaust educator and in carrying out the PhD studies. The school was an inner-city school, in an urban environment in London. A comprehensive, non-selective school of around 1250 students, where all students were day students, and the school had no religious affiliation. The students came from a wide range of socio-economic, ethnic, religious, and cultural backgrounds. Compared to other schools nationally, they had a financially poorer student base with 54.5% students eligible for free school meals at any time during the past 6 years (13.6% being the national average). There were, however, many wealthier students also attending the school. The school became the focus of my study due to ease of access (an opportunity sample)Footnote20 and due to the number of refugee students in mainstream education, which was the reason that this study was started in the first place.

With all this in mind, the study aimed to explore students’ attitudes and engagement with teaching and learning about the Holocaust. Although the students were studied as a whole, as will be discussed below, refugee students were the focus of the study. This was to see whether their lived experiences and conversations from home affected how they felt about learning about the Holocaust and what they learnt from it. Through exploring the national narratives of Holocaust education in a diverse, or international classroom, it was hoped to find out about how students engaged with learning about the Holocaust in more detail.

Ethics process and considerations

Throughout the research ethics was at the forefront of all decisions made. The support of the school was useful in facilitating the administration involved in setting up the research, but additionally, their say over the safeguarding of students was final. The research was based on the BERA guidelines and the school safeguarding policy,Footnote21 and I gained student, teacher and parental consent. Following University guidelines and good practice, I sought approval from an ethics committee prior to carrying out the study, which was granted approval. The research was completed in the best interests of all concerned, following literature and guidance on ethics of working with young people, refugee students and when researching Holocaust Education.

Methodology and methods

Methodology

As Crotty states in his definition of constructivism, ‘truth or meaning, comes into the existence in and out of our engagement with the realities of the world … different people may construct meaning in different ways, even in relation to the same phenomenon.’Footnote22 This was something to consider as the research was looking at refugee students with different lived experiences to those students in the classroom that were born and raised in England. Additionally, I took a pragmatic approach to the research, focusing on ‘what works’ rather than what might be considered absolutely and objectively ‘true’ or ‘real’ and that truth could be judged by its consequence.Footnote23 This idea of interactive, or to some extent, social constructivism straddles both pragmatism and constructivism, and claims that realities are constructed by observers, who are observers are always at the same time agents and participants in cultural practices, routines, and institutions as well.Footnote24 This was particularly relevant considering my experiences as a History teacher teaching the Holocaust in diverse classrooms, and the reasons for starting this research.

This social constructivism, or pragmatic constructivist epistemology was carried out using grounded theory. Grounded theory offered a qualitative approach rooted in ontological critical realism and epistemological objectivity.Footnote25 The end product is conceptualization rather than description; the development of a multivariate theory that accounts for the main concern of participants, and the focus is on what the main concern for participants is and how it is resolved or processed, without any preconceptions of the problem.Footnote26 This was important as the aim of the research was to focus on the student experience, not the teachers.’

Method

To investigate the engagement of Holocaust education, it was important to see the lessons in action, and speak to the students to understand their misconceptions before they started learning about the Holocaust, during and after. I was looking at the experience of refugee students, but it was their wider experiences within a wider classroom setting. As the focus of the research was on students’ experience of learning and their backgrounds, rather than the teachers’ knowledge or practice, it was important that the research centered around the students and their learning. Before and during the study, I had the opportunity to talk to the History teachers, Head of Social Sciences and Head of History. This was important not only to establish what my research was to explore, but to understand the context of the researchFootnote27 within the parameters of the school’s History lessons.

The sample was made up of four Year 9 History classes, each with 30 students, taught by four different teachers. For the interviews, the sample was made up of 20 students, half of whom were of refugee background. Almost half of the interviewees were female, of mixed ethnicity and religion, and 80% of whom were EAL. The refugee students were all first-generation refugees (with one exception below), who arrived in the UK over a year before the studies and had an excellent grasp of English language. All students were studying an enquiry on the Holocaust devised by the History department in the school, based on resources from different Holocaust educational institutions. The topic was the penultimate topic studied before some students dropped History from their education completely. The enquiry approach to learning was taken through the study of resistance and the idea that the Jews did not go ‘like sheep to the slaughter.’ This was not only to rehumanize the individuals and victims, but to understand that the Holocaust does not need to simply be taught perpetrator down. There was an idea from the teachers that there were moral aims in teaching the Holocaust too.

Students were asked what they already knew about the Holocaust before learning it through in-keeping with teachers’ normal practice by reflecting and answering questions on post-it notes at the end of a lesson in the topic prior. Next, I was to observe the students to see what was being learnt, and what could then be developed through interviews.Footnote28 Through observations, I could see the students in their lessons, to understand what the students were learning and their interactions with the lesson content and each other, but also observe things that happen, listen to what is said and note down anything to be questioned during the interviews.Footnote29

The research had two sets of interviews, providing an opportunity for students to verbalize their thoughts and reflections on learning about the Holocaust. The first was a group semi-structured interview, allowing me to establish a positive, encouraging atmosphere to allow the participant to talk freely.Footnote30 The second, at the end of the teaching of the scheme of work, were carried out as individual interviews. All students that were interviewed this time around were present in the group interviews at the beginning. The second set of interviews following up on themes and conversations previous.Footnote31

Once the data were collected, in keeping with the grounded theory, detailed scrutiny of the text followed through a gradual process of coding and categorizing, using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase process of thematic analysis.Footnote32 After coding, the three themes that I came up with were behavioral engagement; cognitive engagement; emotional engagement. These will be explored in the findings below.

Findings and discussion

It must be acknowledged that this data is from my thesis, which explores a number of areas. I will give a precis of the findings here, however within the confines of this article for the discussion that follows I will be focussing on preparation and reflection practices and culture in the classroom in diverse schools.

It was not until I had defined the themes of the data that I defined how I was going to explore engagement of these students. The idea of engagement arose in the classroom and was explored in the classroom. It was split into three strands, behavioral, cognitive and emotional. Behavioral engagement encompasses the involvement of the student in their own learning and academic tasks.Footnote33 As Buhs and LaddFootnote34 define, the measures of behavioral engagement that were relevant for this study include displays of effort, persistence, behavioral aspects of attention – such as involvement in discussions, resilience in completing difficult tasks and purposefully seeking out information without prompting. Emotional engagement is also highly linked to motivation through the student’s emotional reactions to academic subjects or school in general.Footnote35 Because of the sensitive nature of teaching and learning about the Holocaust, the emotional engagement that was explored was both responses to the topic and the teaching of it, and the subject matter. The motivational constructs that can be explored within emotional engagement can also include perceptions of value.Footnote36 The most difficult strand of engagement to define is cognitive behavior.Footnote37 Cognitive engagement encapsulates self-regulation and motivation more than the other strands. To ensure that using cognitive engagement is useful as a dimension to look at (and to avoid conflating it with other constructs), the focus was on what students have learnt and their perceived relevance of learning it and their understanding of the relevance of learning about the Holocaust. It was important to understand that although the themes would be along separate dimensions of engagement, each dimension almost certainly occurs at the same time as others during learning.Footnote38 As an example, students who have a high degree of behavioral engagement may also experience high levels of cognitive and/or emotional engagement, which means that as a researcher I need to be aware of the contributing factors to the evaluation of behavioral engagement from the other dimensions.

The key findings of the study were exciting. The Year 9 students at this school had received a well-intentioned and thorough program of Holocaust education and the teachers were well informed of current practice. The students observed and interviewed had sound academic understanding of the Holocaust, but there still remained some errors and misconceptions that will be explored below. In order to discuss some of the findings in context, I will explore them throughout the three engagement strands.

Behavioral engagement

In order to explore the behavioral engagement of students I observed lessons, noting the time taken on tasks, and the on- and off-task comments made. Interestingly, all students were engaged with learning about the Holocaust. Within this strand, the refugee and non-refugee students had similar patterns of behavior. Although this could be testament to external factors other than the Holocaust education being delivered, the behavioral engagement was, on average, good. However, the behavioral engagement was not as high as the cognitive engagement, which in turn was not as high as the emotional engagement. This could be external, school factors, or additionally because the students are not taught explicitly how to behave when learning about sensitive histories such as the Holocaust. For example, when observing a lesson on ghettos, students in one class went around the classroom looking at what they could learn from the photos. At one point, the teacher had to stop the lesson as a group of girls were stood in front of a photograph and were giggling over it. The teacher told them off for disrespect and had to explain why their behavior was wrong. Although this does not suggest anything like hostility to learning or antisemitism, it could be argued that they were not emotionally mature enough to deal with the content, or perhaps did not understand the context, and laughed as a coping mechanism.Footnote39

The low behavioral instances were few and far between, however. What was interesting from the classroom observations were the areas of what would be described on paper as high levels of behavioral engagement, for example on-task comments, but those that then led to off-task discussions or behaviors. An example of this is when the students made comments that they deem to be related to the topic but are not. Moreover, they are not explored in ways that link them to the topic, merely as an understanding that the students do not offer out loud. For example, when discussing the Nazi persecution of Jews, one student shouted out ‘did you know the Palestinians aren’t allowed to swim on the beaches.’ Although ignored by the teacher, the student then continued this conversation quieter with her friends around her in the class. She later shouted out again, when looking at turning points in the anti-Jewish laws, ‘Public humiliation and removal of territory was an important turning point – just like in Palestine.’ This student was in the interview groups and was a third-generation Iranian refugee. Despite these comments and other quieter, less obtrusive comments in other classes, as CarrFootnote40 also found, she and other students never doubted the historicity of the Holocaust. ShortFootnote41 suggests that the students who antagonize and disrupt the lessons are ‘reluctant learners.’ As a lot of these students were Muslim students, Short suggests that many are reluctant to learn about the Holocaust and are most unlikely to learn from it because of their own antisemitism, but as these comments show, it is more likely that some of this was not underlying antisemitism but more their situational beliefs.

The on-task comments also highlighted different factors of engagement with the different students. One example of positive comments and contributions that students made, whilst engaging in a substantial task was during a lesson looking at forms of Jewish resistance. Within some of the on-task comments made by students, it was sometimes difficult to unpick what are subtle misconceptions and what is antisemitism, but all of these comments were made in response to questions asked by teachers, so could be considered on task. There were a couple that were made to make others around them laugh, which could show a low behavioral engagement, as it immediately takes others off task and shows that they are not interested in the learning.Footnote42 For example, when talking about assimilated Jews, a student stated ‘Sir, I live in a Jewish area. There are loads of Jews in Golders Green,’ which made other students around him laugh nervously. There is scope in the future in looking at why students feel the needs to respond in this way and whether it is the same across all sensitive subjects in History, or all religions, but for now this is focussed on what this means for engagement. A more complex example was in a discussion around the word ‘Jew’ between the students, with the teacher waiting on hand to correct. In the end, the students themselves, got to the final point where a student explained that ‘it’s the way you say it though, if you say, “I’m a Jew” or “you Jew” it’s different, you could be like “I’m Jewish” more than “I’m a Jew”.’

There were on-task comments made that showed misconceptions but led to distractions in class too. So, although this should fall under cognitive engagement in terms of the understanding, it is worth considering the behavioral impacts of the comments. In one class when learning about Nazi persecution and anti-Jewish laws, one student commented ‘what the hell they tryna [sic] starve these people, they not allowed to buy milk or eggs.’ Although this was exactly what he just learnt in a law and could be considered empathetic (see below), the response to this, aside from a ripple of laughter, was to cause some students to become off task and mess around for the rest of the lesson. This was further examined in my thesis looking at the maturity of students to deal with the topic, but some students themselves raised this in the interviews when asked why people should learn about the Holocaust, saw this as their opportunity to talk about the age and maturity of students studying the Holocaust with comments such as ‘obviously not too young … like a teenager or something maybe’; or from a more disruptive student stating ‘old enough to understand it and not be like silly about it.’ Some students were aware of the behavioral implications too, ‘Not everyone should learn it because there’s some people … if they see such information, they probably laugh at it, and you can’t have people like that in such an environment.’ These comments show that some students had an awareness of behavioral concerns, and engagement from this. This could have been from experience in the classroom as was seen in several observations, or through experiences in other subjects with difficult topics too.Footnote43

The relative engagement of students was similar for refugee students and non-refugee students in the classrooms. Perhaps what was most interesting was that the non-refugee students that misbehaved in lessons were the ones that were most disaffected by the subject, but these were not the refugee students in the classrooms.

Cognitive engagement

Within the theme of cognitive engagement, I explored, through the interviews and observations, what students learnt and why this was important, whether there were any patterns in the responses and what these patterns could mean.Footnote44 From analysing their learning journeys to this point, it was clear there was a real mixture of prior encounters with learning about the Holocaust, which in turn shaped their learning and engagement in the History classroom. One thing that was obvious on this point was that comparably, refugee students had had more encounters with the Holocaust through conversations outside the classroom, with friends, family and their communities than other students. One thing of note is that within these conversations with refugee heritage students, the Holocaust was almost always bought up alongside other contemporaneous issues, such as Palestine. The most complicated parts of exploring emotional engagement, were conversations around Israel and Palestine, and some what could be interpreted as antisemitic comments within them. Palestine was mentioned a few times during my observations. This shows a direct link that a certain number of students were making between being told they were going to learn about the Holocaust and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There are elements of emotional engagement that are critically tied up in the cognition of students and their awareness of the world, and this affects how they emotionally engage with the topics in the classroom.Footnote45 As an example, when asked when she spoke about it at home, one student said

first we were talking about Palestine and what was going on and then I was talking to my mum and I was saying … it’s not Jews who have taken over the country, it’s Israelis and I told her … Jews have been through a lot of things the Holocaust and stuff … so … I don’t think we should be blaming … the Jews.

I spent a long time in individual interviews asking students about their prior learning, and if and why they thought they learnt about the Holocaust, whether they thought it was relevant and whether all schools should teach about it. All students resoundingly felt that it was an important and relevant topic, but refugee students were able to better explain why they thought so. Although these same students could not necessarily address what they had learnt well, be that through issues of remembering, the teaching or general articulation of what they had learnt, they had a strong understanding of why they had learnt about it and at why the schools thought it was important for them to learn.Footnote46

One of the key findings from this theme was that many students, mainly refugees, knew what antisemitism was in the context of the Holocaust, thanks to their education, but still held antisemitic views and gave antisemitic responses to some questions. This is not an indictment of the Holocaust education they received, however, as seen in the interviews, most of this came from external factors to school, as one student said it was from her family and where they were from that they all ‘just didn’t like Jews.’ Although refugee students held these views at the same time as experiencing more emotions and discomfort in their study of the Holocaust, refugee students showed the most understanding of what they perceived as the contemporary relevance of the Holocaust, the reason they learn about it and why it is important to learn about it, as well as linking it to other current events. During this learning, it was clear that many students, of all backgrounds, questioned the national narrative of learning about the Holocaust, as it contrasted with their lived experiences and influences from home, in a number of senses. Some students felt that it was odd that outside of lessons, Britain was portrayed as ‘always the good guy,’ and others felt that it was ‘odd that these things are studied when there is still so much bad stuff going on in the world,’ something that is explored further within my thesis.

The students observed and interviewed had sound academic understanding of the Holocaust, but there still remained some errors and misconceptions. For example, some still equated the Holocaust solely with Hitler, some said that the reason Israel existed was because of the Holocaust, and some still felt that although their scheme of learning had been centered on Jewish Resistance in the Holocaust, felt that the ‘Jews were just dragged off one day.’ What was clear from the observations, was the teachers had understood the different backgrounds and some of the cultural beliefs of students in their classes, as well as their abilities. This not only makes the teaching learning centered and helps evaluate progress but ensures that misconceptions are addressed swiftly. Although it is clear some of the preconceptions students had from before their learning still existed, even though they had been challenged and developed from their learning and discussions in the classroom, the levels of understanding, the verbalization of relevance and the comments about all schools teaching the Holocaust, showed a high level of cognitive engagement in all students.

Emotional engagement

Through the emotional engagement theme, I looked at not only how emotionally engaged the students were and their emotional responses to learning about the Holocaust, but also their own awareness of their emotional engagement and that of other people. Learning about the Holocaust had an emotional impact on most refugee and non-refugee students.

Firstly, students were aware that the learning was emotional for others around them, obvious through their awareness of age, when discussing who should study the holocaust. For example, most students saying that to study the Holocaust they should be at least Year 9, and like the student above, a student who understood that people could not cope with such an environment in the classroom. This tied into students who felt that they ‘didn’t really understand it when I was younger, but now I know what racism is, I understand more.’ This linked to the emotional distress realized by non-refugee students. Those who in the interviews made comments about how they found learning about the Holocaust ‘scary,’ ‘distressing,’ ‘evil’ and ‘horrifying.’ It was clear that for these students, that learning about the Holocaust had given them a realization of the evilness of the world. However, for refugee students, their understanding was that the world existed in this way already, both from the vocabulary used to describe it, and the empathetic comments that will be looked at below.

However, it was clear that almost all students were inspired to change their actions and ‘stand up for other people’ through what they had learnt. From ‘raising awareness’ to ‘stopping people who are being racist.’ This was not a message of the teaching they received, but what they had implicitly understood from the topic and believed they should be learning about.

For the majority of students, it emerged through the interviews that learning about the Holocaust had been an emotionally difficult and distressing experience. Students were not thoroughly prepared for their learning beforehand, nor given time to reflect on their learning, emotional or otherwise, because of time constraints and current practice. This led to emotional complexities for students, for example some students who spoke about how upsetting they found it, and that they had spoken to their parents about it which in some cases had made it worse. In other examples, some students said that they did not enjoy learning about the Holocaust even though they knew it was important to. In some cases, it was clear that historical traumas in these students were brought to the surface. In one instance, a student stated that they did not want to talk about their learning as it was too sad for them, as it brought back memories of stories her parents had told her of her life. In another, although she was less forthcoming about her refugee situation and experience, she made comparisons throughout her interview, and used empathetic language when discussing what she had learnt in her studies, particularly when discussing the experience of the victims and travel. It was clear that this student was dealing with emotional distress from making her own comparisons, and we discussed the idea of empathy as well as who she could speak to for more help and information.

However, this trauma led to students becoming more empathetic and knowing what they want their actions to be as a result of their learning. Refugee students’ engagement and understanding of the Holocaust centered around an empathetic understanding, although this was often shrouded in misconceptions of Jews and the consequences of the Holocaust as seen above. These misconceptions, however, did not affect their empathy towards victims they had learned about. This was comparable to non-refugee students saw their learning as an understanding that they were considered mature enough to learn about the evils of the world for the first time.

Good practice states that it is important for teachers to consider the images and stories they show and talk through with students.Footnote47 An exploration of emotions and reactions is more important to have with the students before and during learning about the Holocaust. The Holocaust should be taught as an emotional encounterFootnote48 and teachers need to be more aware of the emotional impact learning about the Holocaust has on students. Students have struggled to understand fully the horrors of what they have learnt and how they feel about it, but are aware that they are only just old enough, or others are too young to learn about it. As teachers, it is our moral duty to ensure the safety and well-being of all students, topics like the Holocaust need to be considered well before teaching. In diverse classrooms this job is more difficult. We cannot just let students enter into learning about the Holocaust without preparation or leave them without the space and skills to discuss it afterwards. It is worth considering some of the good work that has been done on refugee student education in the UKFootnote49 as well as the engagement of students in the classroom when looking at the Holocaust in History education. It is important to consider students’ backgrounds, the affect that this has on their learning and the emotional impact of learning about the Holocaust.Footnote50

Implications and recommendations

The current scope of Holocaust education has shifted significantly over the last five years. It is possible to view some of these findings as failures of Holocaust education within this school, it is also yet another way of understanding the complexity not only of the event, but of teaching about it. While it might be reasonably assumed that all teachers aim to teach their subject with accuracy and passion, this will not always be how students develop their learning.Footnote51 There have been significant developments that have caused setbacks to the development of Holocaust pedagogy. Schools, facing huge budget cuts and increasing costs are meeting timetable needs through getting non-subject specialists to teach History, which means inevitably, non-subject specialists are teaching about the Holocaust.Footnote52 Academies, free schools and independent schools still do not have to follow the National Curriculum, and two terms of online learning due to the global pandemic of COVID-19 might mean many schools avoided teaching the Holocaust as they were worried about teaching such a sensitive topic online.Footnote53

Having presented an overview of the contemporary field of Holocaust education and current practice, alongside the empirical data in the study, I am suggesting four recommendations for amendments to teaching about the Holocaust to develop students’ learning, two will be discussed below, and others are discussed further in my thesis. They are:

Ensure adequate preparation and reflection time are built into the curriculum around encountering the topic of the Holocaust.

Embrace the diversity in the classroom and teach national narratives in an international classroom.

Ensure the culture in the classroom recognizes the aims of teaching about the Holocaust. Ensure the culture in the classroom is safe and inclusive, and one where there is no space for antisemitism. This will ensure all students experiences are incorporated and diversity is embraced.

Develop ways in which understandings of the culture and make-up of the classroom can impact positively on teaching about all sensitive topics in History and other subjects.

This study has shown the Holocaust cannot be taught with just facts alone. The evidence from the data of this research has shown that not only is learning about the Holocaust an emotional experience for students, it can bring up old traumas, create new ones and still leave questions for students around their learning. Students need support to ensure that their learning of the Holocaust helps them understand the world better, and through amending the process of Holocaust education in the ways recommended above, teachers can ensure they help the students understand their learning and assimilate this new knowledge.

Preparation, reflection and refugees

There are clear principles for teaching about the Holocaust in the UK. However, as with some of the other issues in Holocaust education, a lack of clear guidance on how to enact them means that a level of ambiguity encompasses all work created by teachers and educators. The significant IHRA principle in light of this research is principle 3.2.2 in which it states that

Classrooms are rarely homogeneous … public debate and current political issues will affect how learners approach the topic. The diverse nature of each classroom and ongoing public debates offer multiple possibilities to make the Holocaust relevant for learners and engage them in the topic … Some learners who feel that the historical or contemporary suffering and persecution of groups they identify with has not been addressed may be resistant to learning about the persecution and murder of others … .Footnote54

It is this principle that needs developing to ensure that diverse classrooms are prepared for learning about the Holocaust. It is paramount that adequate preparation and reflection time is given when studying the Holocaust, and that this time is meaningful. Students need to be and believe they are in a safe learning environment to explore the complex history and their own emotions about it. There needs to be preparatory work with students, before exposing them to the topic. It was clear from the findings that students did not know what to expect when they were learning about the Holocaust which furthered some of the trauma experienced.

It was important for students to have had conversations about empathy and comparisons, which, although difficult, are necessary. It is important to have empathy within History teaching,Footnote55 where empathy is perspective recognition and caring. The difficulties with sensitive topics like the Holocaust is that the cognitive dimension of this empathy includes reconstructing the past and recognizing perspectives, as well as the affective dimension of sensing with one’s own emotions how people in the past would have functioned,Footnote56 something that is advocated against in all principles of Holocaust education pedagogy.Footnote57 These conversations are important therefore, to ensure that students that are more prone to this empathy are not placing themselves in the victims’ shoes, both for good pedagogy and their own safeguarding of bringing up past traumas. It is understandable that with enquiry-based learning in HistoryFootnote58 teachers may not want to have some of these preparatory conversations at the beginning of the learning for fear of ‘ruining’ the surprise of the enquiry. This however is easy to avoid by being more general with explanations and preparatory conversations. It is important to remember that these conversations will help enhance the learning and engagement for all students in the classroom, rather than decrease their engagement. It was clear from the research that refugee students in particular empathized significantly more throughout the learning and on reflection than other students. This is novel when looking at refugee students learning about the Holocaust. Sympathy and empathy demand some common experience, which is what some of these students may relate to.

We must ensure that students understand that emotions are a source of knowledge. By using trauma-informed teaching practice,Footnote59 teachers can recognize students’ existing trauma and ensure that nothing further is caused that could be avoided. Conversations need to recognize and acknowledge that learning about mass violence can be traumatic and reassure students they are in a supportive and safe learning environment. It is paramount to examine the historical and contemporary connections without comparing them and is vital that students know that learning about the Holocaust is complex, and their educators will not be simplifying it for them. Educators need to not dictate any expected emotions from the students. This research has shown that those expectations, when not met can cause disengagement, and they do not allow for the fact that all students react differently when learning about the Holocaust.

It is important to explore the idea of empathy and its complications. This research has shown that refugee students showed more empathy towards the victims in the Holocaust and so experienced more emotions and emotional discomfort during their studies. Because of this, conversations must be had with students before they start learning about the Holocaust. Teachers must ensure that their teaching helps students understand and rehumanize attitudes and actions in a historical context, both of victims and perpetrators. Teachers must, however, explain and explore why it is important for students to not imagine themselves in the situation, put themselves in victims,’ rescuers,’ bystanders’ or perpetrators’ shoes.Footnote60 Rather, they should be encouraged to see these people as individuals, and, using testimony, understand why they made the decisions or held the attitudes they held. The empathy employed by the students’ needs to be to make the History real, as Barton and LevstikFootnote61 argue both types of empathy that were mentioned above are important to connect emotionally with the subject, but empathy alone is insufficient for learning as it needs to be historically contextualized, which can happen through these conversations. Therefore, students do not need to put themselves in the shoes of the victims, as this understanding helps students discuss the complexities of the Holocaust more meaningfully, and keeps students emotionally and cognitively engaged, and safe. The conversations held must explain to students that as they were not there, and can never be, they cannot empathize with victims or others fully, and it is dangerous to do so as it loses the historical accuracy of how these things happened. Students must make connections with what they are learning to contemporary events without making comparisons.Footnote62 It is important here to distinguish between the history of the Holocaust, and what can be learnt from that history. These conversations need to take place before learning so that students can feel involved, emotionally, cognitively and behaviorally, and can ensure that they are not put through emotional turmoil learning about the Holocaust. This is particularly important with refugee students, as teachers often do not know their stories and situations, and it is important that the suffering of others is not compared or appropriated.

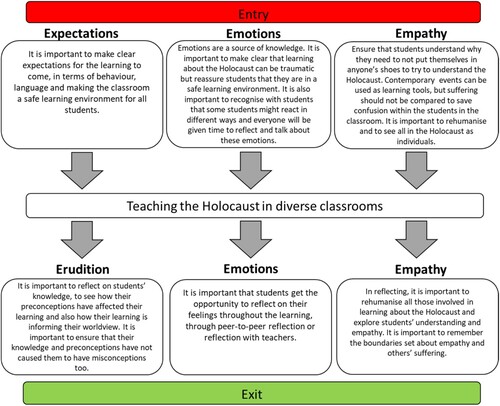

This research has shown that there is a gap in what exactly might be needed for the preparation and reflection stage. Therefore, I am suggesting that for the preparation, or entry into learning, there are three considerations as seen in below. The reflection, or exit process needs to be similar. It is paramount that students feel that they are in a safe space to process their emotions throughout, and there needs to be space for students to reflect at the end of every lesson, not just at the end of the unit of work or day of study. Different aspects of the topic affected different students, which shows the importance of continual reflection, not just at the end.

Figure 1. The six Es model for entrance into, and exit out of Holocaust learning.

These recommendations ensure that all the emotional complexities evident in the research and the empathy and understanding from refugee students as well as the poor behavioral and emotional engagement that was explained by some students’ attitudes in the interviews, are all prepared for and expectations are set for students and teachers. These recommendations are not intended to replace the principles that exist for teaching and learning about the Holocaust, but to compliment them and provide additional guidance on how to ensure diverse classrooms are successful. This recommendation therefore is for thorough and built-in preparatory conversations before learning about the Holocaust, and meaningful reflection afterwards to minimize trauma and ensure that the Holocaust is taught well, and safely. As the Holocaust slides from living memory, we need to ensure that it is taught well to ensure no disservice to those that died or survived, or to the students that learn about it for the first time. It is complex enough in its history and chronology that we need to help work through the emotional complications that come with it. After all, student well-being is a moral duty for all teachers and educators.Footnote63

Culture in the classroom

Through the discussions arising from the Black Lives Matter movement and subsequent outpouring of antisemitic social media posts from one of the biggest UK grime artists, Wiley,Footnote64 that the importance of this study and its implications became clearer to me. In 2018, the CST recorded its highest number of antisemitic incidents reported since its establishment in the 1990s. The number has risen each yearFootnote65 and became particularly prevalent when antisemitism became part of political discourse and a media focus. The rise in reported antisemitism is not just a British issue.Footnote66

The most common way governments seek to deal with this is through Holocaust education. If that is an aim of Holocaust education, (which some Holocaust Educational institutions are pushing, and some are avoiding) what we teach needs to change to ensure students understand the history of antisemitism, antisemitism in pre-war Jewish life, during the Holocaust, and since liberation. However, addressing and dealing with antisemitism through teaching and learning about the Holocaust could be problematic and lead to more issues than it solves.Footnote67 Nevertheless, the British government have used the rise in antisemitism to legitimise Holocaust education in order to combat antisemitism.Footnote68 If, however, Holocaust education is the answer to combatting antisemitism then the nature of the antisemitism needs to be explored further.Footnote69 This is not new, or something that is exclusive to antisemitism. There have been increased calls to look at how British colonialism and Black History, in particular the Slave Trade, is taught to combat the issues of racism in British society.Footnote70 To combat antisemitism in the classroom rather than just learn about the Holocaust and Nazism, it is important to explore what exists in the classroom and how this develops, as well as the schools’ cultures.

This research shows that students were aware of what antisemitism is, being able to give definitions of what it is and how it was part of the Holocaust. It also showed that students, especially refugee heritage students, held a large number of antisemitic sentiments, some ignored by teachers for behavior management purposesFootnote71 and in some cases because the teacher did not feel confident in tackling the problem head on. If the Holocaust is taught even partly to educate against antisemitism, then students and teachers need to be conscious of the similarities and differences of antisemitism then and contemporary antisemitism, and teachers need to have the confidence to pull students up on antisemitic comments. Without a hard line on antisemitism in the classroom from teachers, it is easy for students to learn about the Holocaust still holding contemporary antisemitic views which are not challenged by the classroom culture, as it is clear that in some cases in this research, students felt like there was no such thing as antisemitism anymore as Hitler lost the war.

There are other aspects of classroom learning culture that are important to consider. The Israel-Palestine situation, antisemitic comments over this and the what about ‘others’ (be that victims of Nazi persecution or studying other genocides). It was clear from the research that a number of students were very concerned about the Israel-Palestine connections to both their own story and of what they were learning. Some students held strong personal views, but these students were also those who were most engaged and could articulate the relevance of learning the Holocaust the most, many being refugee students. This is something that schools need to prepare for particularly around times of heightened conflict in the region. The national narrative of learning about the Holocaust is also seen on a smaller scale when we look at the culture of schools.Footnote72 It could be questioned that by imposing the schools’ moral standards on students, we are expecting, in the case of refugee students as a clear example, students to be antiracist, but this blanket term does not allow for diversity and ignores individuals.Footnote73 For the purposes of this article, antisemitism comes under the umbrella term of racism. This anti-racism culture in schools therefore expects students to take part in being anti-racist, and for some refugee students holding these views, if not explained properly because of the lack of understanding of the diversity of students in the schools, they could be amplified when learning about the Holocaust. Some students, as seen in this research, did not think that they were being racist with their views, it was just their experience. By listening to the story of Jews in the classroom and being told to withhold their views, or not acknowledge them, this might cause those antisemitic feelings to be pushed further underground and be harbored until those students are out of the ‘anti-racist’ environment. To counteract this, meaningful antiracist education is needed, antiracist education that does not cover over, or belittle the experiences of refugees or other students in the classroom who may have experiences that lead to their worldview. It is one of the fundamental parts of refugee education, to embrace the diversity (Rutter, Citation2006) and if this means to acknowledge racist views in the classroom before exploring them more, then this is necessary.

The recommendation here is that once students have been prepared for what they are studying, the diversity of the classroom has been embraced and reflections built in, students need to learn about antisemitism. The long history of it, to not just know what the word means, but to see how this is relevant to their learning but also contemporary understanding of antisemitism. There is an element of teacher confidence that comes in to play hereFootnote74 but there is also a need to change what is taught when teaching about the Holocaust.

As Mohamud and WhitburnFootnote75 state, doing justice to history is different to doing justice to other disciplines because of the moral and intellectual dimensions, and as justice arises in all topics. Throughout this research, even the students with blatant antisemitic views, did not have a lack of engagement or enthusiasm in learning about the Holocaust, which is positive, as non were ‘reluctant learners.’Footnote76 There was also very little resentment of learning about the Holocaust from students who believed their backgrounds should be studied too. Significantly, this gives hope and excitement that learning about the Holocaust is as relevant now as it ever has been.

Conclusion

This research showed that the Holocaust was well received by all students learning about it. Through looking at refugee students in mixed classes, and exploring their behavioral, cognitive and emotional engagement with the subject it was clear that refugee students were far more engaged on all levels. By implementing the recommendations above and finding a way to do so, students can begin to understand the complexity of the Holocaust whilst developing their diverse experience of learning about it with less trauma and more understanding of its contemporary relevance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jessica Kempner

Jessica Kempner is head of History, Politics and Sociology at a comprehensive school in London. A refugee mentor, educator for the Holocaust Educational Trust and teacher, she has undertaken multiple courses in Holocaust education and teacher study visits. She received her PhD exploring refugee engagement with Holocaust education (based on her experiences in the classroom), from the University of Winchester.

Notes

1 Kempner, Refugee Engagement, 1–258.

2 Robson, Real World Research, 158.

3 Department for Education, National Curriculum.

4 Pearce, Holocaust in the National Curriculum.

5 Pettigrew, Why Teach or Learn about the Holocaust, 263.

6 The Refugee Council, Case for Change.

7 See for example here Montgomery, Trauma, Exile and Rutter, Refugee Children.

8 Rutter, Refugee Children.

9 Block et al., Supporting Schools.

10 Chase et al., The Emotional Wellbeing, 89.

11 Roy and Roxas, Whose Deficit is This.

12 Wilkinson et al., Sudanese Refugee Youth.

13 Baak, Racism and Othering.

14 Rutter and Jones, Refugee Education.

15 NALDIC, Guidelines.

16 Ofsted, The Education Inspection Framework.

17 Home Office, Prevent Strategy.

18 Ibid.

19 Shackle, Trojan Horse Article.

20 Cohen et al., Research Methods in Education.

21 BERA, Ethical Guidelines.

22 Crotty, Foundations of Social Research, 9.

23 Festenstein, Pragmatism and Political Theory.

24 Neubert and Reich, The Challenge of Pragmatism.

25 Annells, Grounded Theory Method.

26 Alvita and Andrews, Modifiability of Grounded Theory.

27 Atkins and Wallace, Research Methods.

28 Denscombe, Good Research Guide.

29 Becker and Geer, Participant Observation and Interviewing, 33.

30 Drever, Using Semi-Structured Interviews.

31 Denscombe, Good Research Guide.

32 Braun and Clarke, Using Thematic Analysis.

33 Fredericks, Engagement in School.

34 Buhs and Ladd, Peer Rejection.

35 Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, Academic Emotions.

36 Schunk et al., Motivation in Education.

37 Fredericks, Engagement in School.

38 Sinatra et al., Challenges of Defining and Measuring.

39 Pollak and Freda, Humour, Learning and Socialization.

40 Carr, How Do Children Respond.

41 Short, Reluctant Learners, 1.

42 Fredricks, Engagement in School.

43 Burnett, Teacher Praise.

44 Denscombe, Good Research Guide.

45 Brina, Not Crying, but Laughing; Burke, Death and the Holocaust; Clements, A Very Neutral Voice.

46 Fredericks, 2011.

47 IHRA, 2019.

48 Richardson, Citation2012.

49 Bloch, Citation2018; Rutter Citation2006 as examples.

50 Brina, Citation2003; Burke, Citation2003.

51 An example here is Pearce, Challenges, Issues and Controversies.

52 Pettigrew et al., Teaching about the Holocaust; Foster et al., What Do students Know.

53 As this is relatively new there is not much published. One teacher’s reflections on this for the CHE can be found here https://www.holocausteducation.org.uk/teaching-holocaust-lockdown-teacher-reflections-challenges-opportunities/ [accessed 17/11/2020].

54 IHRA, Recommendations, 27.

55 Barton and Levstik, Teaching History.

56 Ibid.

57 IHRA, Recommendations.

58 Mohamud and Whitburn, Doing Justice to History.

59 Carello and Butler, Potentially Perilous Pedagogies; Crosby et al., Social Justice Education.

60 Clements, A Very Neutral Voice; Gubkin, Empathetic Understanding.

61 Barton and Levstik, Teaching History.

62 Cowan and Maitles, Developing Positive Values.

63 DfE, Teachers Standards.

64 See https://inews.co.uk/news/uk/wiley-tweets-anti-semitic-what-say-twitter-grime-artist-explained-563487 [accessed 15/8/2020].

65 Community Security Trust, Antisemitic Incidents Report 2018.

66 European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Fundamental Rights Report, 19.

67 UNESCO and OSCE, Addressing Antisemitism; Pearce, Challenges, Issues and Controversies.

68 Pearce, Britishness, Brexit and the Holocaust; Pickles, Anti-Semitism Speech.

69 Pearce, Challenges, Issues and Controversies.

70 For example, see https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/jun/08/calls-mount-for-black-history-to-be-taught-to-all-uk-school-pupils [accessed 25/8/2020].

71 Parsonson, Evidence Based Classroom Behaviour.

72 Pearce, Britishness, Brexit and the Holocaust.

73 Dei, Critical Perspectives.

74 Foster et al., What Do Students Know.

75 Mohamud and Whitburn, Doing Justice to History.

76 Short, Reluctant Learners, 1.

References

- Alvita, N., and T. Andrews. “The Modifiability of Grounded Theory.” The Grounded Theory Review 9, no. 1 (2010): 65–76.

- Annells, M. “Grounded Theory Method, Part I: Within the Five Moments of Qualitative Research.” Nursing Inquiry 4, no. 3 (1997): 176–180.

- Atkins, L., and S. Wallace. Research Methods in Education: Qualitative Research in Education. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012.

- Baak, M. “Racism and Othering for South Sudanese Heritage Students in Australian Schools: Is Inclusion Possible?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 6 (2018): 1–17.

- Barton, K., and L. Levstik. Teaching History for the Common Good. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004.

- Becker, H., and B. Geer. “Participant Observation and Interviewing: A Comparison.” Human Organization 16, no. 3 (1957): 28–35.

- Bloch, A. “Talking About the Past, Locating It in the Present: The Second Generation from Refugee Backgrounds Making Sense of Their Parents’ Narratives, Narrative Gaps and Silence.” Journal of Refugee Studies 31, no. 4 (2018): 647–663.

- Block, K., S. Cross, E. Riggs, and L. Gibbs. “Supporting Schools to Create an Inclusive Environment for Refugee Students.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18, no. 12 (2014): 1337–1355.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, no. 2 (2006): 77–101.

- Brina, C. “Not Crying, but Laughing: The Ethics of Horrifying Students.” Teaching in Higher Education 8, no. 4 (2003): 517–528.

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. 4th ed. London: BERA, 2018. https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethicalguidelines-for-educational-research-2018.

- Buhs, E. S., and G. W. Ladd. “Peer Rejection as Antecedent of Young Children’s School Adjustment: An Examination of Mediating Processes.” Developmental Psychology 37, no. 4 (2001): 550–560.

- Burke, D. “Death and the Holocaust: The Challenge to Learners and the Need for Support.” Journal of Beliefs and Values 24, no. 1 (2003): 53–65.

- Burnett, P. C. “Teacher Praise and Feedback and Students’ Perceptions of the Classroom Environment.” Educational Psychology 22, no. 1 (2002): 5–16.

- Carello, J., and L. Butler. “Potentially Perilous Pedagogies: Teaching Trauma is Not the Same as Trauma-Informed Teaching.” Journal of Trauma and Dissociation 15, no. 2 (2014): 153–168.

- Carr, H. “How Do Children in an Egyptian International School Respond to the Teaching of the Holocaust?” Unpublished M.Ed thesis, University of Hull, 2012.

- Chase, E., A. Knight, and J. Statham. The Emotional Well-Being of Young People Seeking Asylum in the UK. London: British Association for Adoption and Fostering (BAAF), 2008.

- Clements, J. “A Very Neutral Voice: Teaching About the Holocaust.” Educate 5, no. 2 (2006): 39–49.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, et al. Research Methods in Education. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

- Community Security Trust. Antisemitic Incidents Report 2018. London: Community Security Trust, 2018. Online. https://tinyurl.com/sjxjy2p.

- Cowan, P., and H. Maitles. “Developing Positive Values: A Case Study of Holocaust Memorial Day in the Primary Schools of one Local Authority in Scotland.” Educational Review 54, no. 3 (2002): 219–229.

- Crosby, S., P. Howell, and S. Thomas. “Social Justice Education Through Trauma-Informed Teaching.” Middle School Journal 49, no. 4 (2018): 15–23.

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. London: SAGE Publications Inc, 1998.

- Dei, G. J. S. “Critical Perspectives in Antiracism: An Introduction.” Canadian Review of Sociology 33, no. 3 (1996): 247–267.

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Social Research Projects. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2007.

- Department for Education. The National Curriculum in England: Framework Document for Consultation, February. London: HMSO, 2013.

- DfE. Teachers’ Standards: Guidance for School Leaders, School Staff and Governing Bodies. Crown copyright, 2011.

- Drever, E. Using Semi-Structured Interviews in Small-Scale Research – A Teacher’s Guide. Edinburgh: SCRE Publications, 2003.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Fundamental Rights Report. Accessed June 21, 2020. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2020-fundamental-rights-report-2020_en.pdf, 2020.

- Festenstein, M. Pragmatism and Political Theory: From Dewey to Rorty. Polity, 1997.

- Foster, S., A. Pettigrew, A. Pearce, R. Hale, A. Burgess, P. Salmons, and R.-A. Lenga. “What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust?” Evidence from English Secondary Schools (UCL) (2016): 1–286.

- Fredricks, J. “Engagement in School and Out-of-School Contexts: A Multidimensional View of Engagement.” Theory Into Practice 50, no. 4 (2011): 327–335.

- Gubkin, L. “From Empathetic Understanding to Engaged Witnessing.” Teaching Theology and Religion 18 (2015): 103–120.

- Home Office. Prevent Strategy, 2011. Accessed October 8, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/97976/prevent-strategy-review.pdf.

- International Holocaust Rememberance Alliance (IHRA). Recommendations for Teaching and Learning About the Holocaust. Salzburg: IHRA, 2019. Accessed January 1, 2020. https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/sites/default/files/inline-files/IHRA-Recommendations-Teaching-and-Learning-about-Holocaust.pdf.

- Kempner, J. “Refugee Student Engagement with Holocaust Education.” PhD thesis. University of Winchester, 2021.

- Mohamud, A., and R. Whitburn, eds. Doing Justice to History: Transforming Black History in Secondary Schools. UCL IOE Press, London, 2016.

- Montgomery, E. “Trauma, Exile and Mental Health in Young Refugees.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 124 (2011): 1–46.

- NALDIC. 2017. Online. Accessed October 8, 2017. https://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-teaching-and-learning/outline-guidance/ealrefugee/.

- Neubert and Reich. “The Challenge of Pragmatism for Constructivism: Some Perspectives in the Programme of Cologne Constructivism. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy.” New Series 20, no. 3 (2006): 165–191.

- Ofsted. The Education Inspection Framework. Manchester. Accessed November 14, 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/801429/Education_inspection_framework.pdf, 2019.

- Parsonson, B. “Evidence-Based Classroom Behaviour Management Strategies.” Kairaranga 13, no. 1 (2012): 16–23.

- Pearce, A. “The Holocaust in the National Curriculum After 25 Years.” Holocaust Studies 23, no. 3 (2017): 231–262.

- Pearce, A. “Challenges, Issues and Controversies: The Shapes of ‘Holocaust Education’ in the Early Twenty-First Century.” In Holocaust Education: Contemporary Challenges and Controversies, edited by S. Foster, A. Pearce, and A Pettigrew, 1–27. London: UCL Press, 2020a.

- Pearce, A. “Britishness, Brexit and the Holocaust.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Britain and he Holocaust, edited by T. Lawson and A. Pearce, 469–506. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020b.

- Pekrun, R., and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia. “Academic Emotions and Student Engagement.” In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement, edited by S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie, 259–282. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, 2012.

- Pettigrew, A. “Why Teach or Learn About the Holocaust? Teaching Aims and Student Knowledge in English Secondary Schools.” Holocaust Studies 23, no. 3 (2017): 263–288.

- Pettigrew, A., S. Foster, J. Howson, P. Salmons, R.-A. Lenga, and K. Andrews. “Teaching about the Holocaust in English Secondary Schools: An Empirical Study of National Trends, Perspectives and Practice”, 2009.

- Pickles, E. “We shall Tackle Anti-Semitism.” Speech, January 21. Online. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/we-shall-tackle-anti-semitism, 2015.

- Pollak, J. P., and P. Freda. “Humor, Learning, and Socialization in Middle Level Classrooms, The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies.” Issues and Ideas 70, no. 4 (1997): 176–178.

- The Refugee Council and The Children’s Society. A Case for Change: How Refugee Children in England are Missing out. London: Refugee Council and The Children’s Society, 2002.

- Richardson, A. J. “Holocaust Education: An Investigation into the Types of Learning that Take Place When Students Encounter the Holocaust.” Doctor of Education thesis, Brunel University, 2012.

- Robson, C. Real World Research. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

- Roy, L., and K. Roxas. “Whose Deficit Is This Anyhow? Exploring Counter-Stories of Somali Bantu Refugees’ Experiences in ‘Doing School’.” Harvard Educational Review 81 (2011): 521–542.

- Rutter, J. Refugee Children in the UK. Berkshire: Open University Press, 2006.

- Rutter, J., and C. Jones. Refugee Education: Mapping the Field. Trentham: Stoke-on-Trent, 1998.

- Schunk, D., J. Meece, and P. Pintrich. “Motivation in Education: Theory, Research and Applications”, 2013.

- Shackle. Accessed June 21, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/01/trojan-horse-the-real-story-behind-the-fake-islamic-plot-to-take-over-schools, 2017.

- Short, G. “Reluctant Learners? Muslim Youth Confront the Holocaust.” Intercultural Education 24, no. 1–2 (2013): 121–132.

- Sinatra, Gale M., Benjamin C. Heddy, and Doug Lombardi. “The Challenges of Defining and Measuring Student Engagement in Science.” Educational Psychologist 50, no. 1 (2015): 1–13.

- UNESCO and OSCE. Addressing Antisemitism Through Education: Guidelines for Policymakers. Paris, UNESCO UN General Assembly (1949). Paris: Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 2018.

- Wilkinson, J., N. Santoro, and J. Major. “Sudanese Refugee Youth and Educational Success: The Role of Church and Youth Group in Supporting Cultural and Academic Adjustment and Schooling Achievement.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 60 (2017): 210–219.