ABSTRACT

This paper examines how international, large-scale skills assessments (ILSAs) engage with the broader societies they seek to serve and improve. It looks particularly at the discursive work that is done by different interest groups and the media through which the findings become part of public conversations and are translated into usable form in policy arenas. The paper discusses how individual countries are mobilised to participate in international surveys, how the public release of findings is managed and what is known from current research about how the findings are reported and interpreted in the media. Research in this area shows that international and national actors engage actively and strategically with ILSAs, to influence the interpretation of findings and subsequent policy outcomes. However, these efforts are indeterminate and this paper argues that it is at the more profound level of the public imagination of education outcomes and of the evidence needed to know about these that ILSAs achieve their most totalising effects.

Introduction: international large-scale assessments and their networks

International large-scale assessments (ILSAs) explicitly aim to influence policy. One way they do this is through reports and presentations targeted directly at policymakers and government officials. Another way is by disseminating information in the public domain through a range of media outlets. This paper explores how international assessments engage with the broader societies they aim to serve and improve. In particular, it presents evidence about the discursive work done by different agencies, interest groups and the media through which the findings become part of public conversations and are translated into usable form in policy arenas. While international comparisons in the school sector, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s influential Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) are well known, there is a proliferating range of such studies, each with their own characteristics and methodologies, aiming to influence other sectors of education including early years education, vocational skills training, adult lifelong learning and higher education. In turn, these connect with key indicators for other areas of social policy. The ever-widening reach of ILSAs has the potential to assemble new educational realities and publics, not just directly through national policy reforms but also through the ways in which ILSAs enter public discourse and shape common sense understandings of what is valuable in education, its legitimate goals, who teachers and students are, what they should be doing and how it is possible to compare and know about the achievements and practices of different educational systems. International agencies and national actors alike are investing heavily in the creation of this new reality.

Existing research has documented the ‘knowledge networks’ that form in relation to ILSAs (see for example Grek, Citation2010; Morgan, Citation2007; Ozga, Dahler-Larsen, Segerholm, & Simola, Citation2011). These networks include numerous interest groups and publics: advocacy groups, policymakers and their research bodies, commercial organisations, academics and ultimately parents, students and the general public. Each of these groups has their own interests and priorities which shape their responses to ILSA findings. Moreover, the implications of policies such as the introduction of standardised systems for monitoring achievement or value for money extend beyond education to other social policy areas and to the financial and economic sectors of government which may be actively involved in circulating and interpreting the findings (see e.g. Grek, Citation2008).

The concept of mediatisation (Lundby, Citation2009) draws attention to the influence of an increasingly ubiquitous and diverse media on culture and society. This raises important issues about the significance of print publications, the broadcast media and other types of public communication in the formation of public discourse and policy production around ILSAs. To understand these issues, research is needed to explore how assessment findings are promoted, publicised and received – and by whom.

While the idea of mediatisation implies an important role for the media in relation to national educational policy formation, most of the research evidence about this link is indirect. Researchers are beginning to understand more about the media as players in a wider discursive mix, the effects of media interest and coverage in particular contexts, how these are achieved and what other factors might determine reception and policy response. Rawolle (Citation2010) provides a nuanced account of the diversity of journalistic response in the print media in relation to a policy reform that implicated science education, while Blackmore and Thorpe (Citation2003, p. 594) conclude from their study of school reform in Australia, that ‘the media is itself a contested and relatively autonomous domain’ which subjects publics, politicians and bureaucrats ‘to the unpredictability of mediated discourses around education’.

However, politicians, advocacy groups and bureaucratic players are far from being passive subjects. They are proactive in their attempts to strategically manage media coverage and public opinion – both promoting and responding to these. The process of translating the scientific facts of the surveys into public knowledge, acceptable bases for action (or non-action) is thus a tug of war of uncertain outcome. Further, the media themselves are highly diverse in their reach – that is, they vary in who they target, who engages with them as consumers and producers of news and the degree of interactivity they afford. It is therefore important to explore what different media contribute to public discourse including digital, interactive media as well as the more traditional print and broadcast media.

A range of conceptual frameworks are available to aid such explorations. Two of these are used in this paper to orient the discussion and to analyse the case study presented in Section 3.

Firstly, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a helpful approach since it asserts that it is important to study discourse in relation to policy action because it plays a key role in social change (Fairclough, Citation2000). The term discourse can cover the use of all symbolic resources in creating meaning, not just language (see O’Halloran, Citation2005; Van Leeuwen, Citation2008). Specifically, in the discourse of ILSAs, visualisations and the symbolic resources of number are prominent and these will be briefly discussed.

CDA theorists, such as Chouliaraki and Fairclough (Citation1999) offer tools for analysing the relationship between discourse and social action. They argue that social changes exist as discourses as well as processes; change is ‘talked into being’ through discourse terms such as ‘the global knowledge economy’, ‘failing schools’, ‘essential skills’ or ‘national prosperity’. In relation to ILSAs, discourses frame both the international and the national debates, valorising certain sources of evidence and assembling and normalising what Pons (Citation2012) calls ‘argumentaires’ – coherent sets of warrants that legitimise the claims made about ILSAs and the nature of desirable policy reforms.

Hamilton and Pitt (Citation2011) argue that these discursive acts shape action within and across social practices. What is valued and funded in an education system is shaped by the prevailing discourses of international skills assessments and these in turn may have material impact on curricula, teacher practices and identities through the penalties and incentives associated with them. Lewis and Hardy (Citation2015), for example, document the influence of the Australian NAPLAN reporting system on the institutional life of schools and teacher subjectivities as it encourages risk-reducing ‘gaming’ and avoidance of innovation through norms and penalties that entangle teachers in a contradictory imperative that says ‘improve’ but ‘don’t improve too much’. Such perverse effects are widely documented within the educational literature and beyond (Lingard & Sellar, Citation2013; Pidd, Citation2005; Shore & Wright, Citation2015).

The second approach used in this paper is that of actor-network theory (ANT). This complements discourse analysis and is particularly relevant to understanding the growing momentum of an innovative social project like ILSAs (Fenwick, Edwards, & Sawchuk, Citation2015). Gorur (Citation2011) uses this approach to analyse how international skills assessments are framed and defined in ways that can resonate with the interests of the wide range of players that have to be brought together to realise the success of the surveys. This work can be extended to examine how ILSAs constitute and interest the publics who must be engaged if the surveys are to effect change and to identify the allies and adversaries who are active in the ILSA networks as the survey findings seek entry into national contexts.

To this end, the paper is divided into three main sections. The first deals with how ILSAs mobilise entry into the individual countries that are the units of comparison. The second looks at how public awareness and opinion are managed through the release of findings to the media, using the example of the OECD’s survey of adult skills, the Programme of International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). The third section reviews some evidence about how the ILSA findings are presented and interpreted in the media and how potential reforms of policy and practice are subsequently construed in relation to them. The paper concludes that the results of efforts to mobilise ILSAs in terms of specific national policy reforms are indeterminate but, at a more profound level, ILSAs are transforming the public imagination of education outcomes and of the evidence needed to know about these. I use the approaches of CDA and ANT outlined above as methodological orientations to this topic, but it is not within the scope of the paper to apply them in detail.

Mobilising national actors

A first move in mobilising the network around ILSAs is to gain the consent and active engagement of national governments and publics with the developing assessments. This process of mobilisation and merging of interests starts early in the conceptualisation and construction of the tests themselves, but continues throughout the assembling and diffusion of the findings. It has a significant discursive component as arguments are advanced and documents are produced, adjusted and agreed with the aim of engaging particular groups (see Carvalho, Citation2012; Sellar & Lingard, Citation2013b).

The international surveys coordinated by the OECD are important examples of how knowledge networks are assembled. The surveys are conducted by individual countries who volunteer to take part and pay for much of the operational costs of doing so. Persuading governments to participate therefore entails a financial and logistical commitment from them as they weigh up the costs and benefits of their participation and ponder how the assessments will fit within national contexts whether practically, fiscally or in terms of existing policy priorities. Access must be negotiated with individual countries and not every country chooses to take part in every assessment. Even after countries are enrolled in the assessment network, their continued participation is not guaranteed, especially if the results do not show the country in a good light. For example, Colmant (Citation2007, p. 75) and Pons (Citation2011) describe how France has participated selectively in international assessments of literacy and has disputed the findings of the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) in their country. Similarly, the U.K. has a well-developed national assessment system of its own and has not always opted to participate in international assessments.

Addey and Sellar (Citation2017) write about the diverse motivations driving countries to participate in international assessment programmes even if they are likely to achieve only a low ranking (and see Bolívar, Citation2011). These motivations include not only a desire for evidence to reform educational systems but also the need to build technical capacity in assessment methods, accessing funding and aid and developing positive international relations. Addey’s own research in the Lao PDR and Mongolia (Addy, Citation2015), suggests that low-income countries like these join ILSA programmes as part of what she calls ‘a global ritual of belonging’. Other countries, in contrast may value the ‘glorification’ (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2003) of their education system offered by high positions in the international league tables.

Richardson and Coates (Citation2014) describe feasibility studies carried out for the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) programme in a range of different countries, especially issues around motivation and the varying responses of those countries to the idea of assessing university student learning outcomes. The degree to which this programme has succeeded in mobilising key national players makes AHELO an interesting case because it encountered considerable institutional resistance unlike the more popular, media-led, global university rankings that are now a significant factor in decision-making among university management in many countries (see O’Connell, Citation2015; Shore & Wright, Citation2015; Stack, Citation2016). A similar contrast can be seen between PISA which seems to go from strength to strength despite critiques of its validity (Meyer & Benavot, Citation2013), and the more recent assessment of adult skills (PIAAC) which has attracted comparatively little attention so far from either the media or national policy communities (see Clair, Citation2016; Cort & Larson, Citation2015; Yasukawa, Hamilton, and Evans (Citation2016)). While ILSAs may become more visible and accepted in the media and public discourse over time as Mons, Pons, Van Zanten and Pouille (Citation2009) found in their coverage of PISA in France, the picture emerging from these studies is of a graduated response that suggests a complex network of influences at play.

Having secured participation of countries, all the international agencies such as the OECD, UNESCO and the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) have communication strategies in place to promote and publicise the survey data when they have been collected and analysed (see Lingard’s Citation2016 example of the OECD). Agencies present a range of carefully crafted artefacts to the media and national stakeholders. The release of the findings is carefully timed and managed, both internationally and within individual countries with approved media and selected national stakeholders, given embargoed access to the results days ahead of the release.

The OECD offers copious information about its survey results online, in print and via webinars and videos, explaining how the test is constructed, how the surveys are carried out, the methodological issues arising, findings for individual countries and policy guidance for them, as well as the familiar league tables that show participating countries ranked in terms of subject domains and scores. The Director of Education and Skills at the OECD, Andreas Schleicher, is prominent in promoting the findings, speaking at invited seminars and offering webinars and media interviews as well as writing blogs (Schleicher, Citation2016) and academic articles (Schleicher, Citation2008).

Managing the release and interpretation of findings: the case of PIAAC

As an example, we can look at the release of the second round findings from the OECD’s adult skills survey, (PIAAC), on 28 June 2016. This survey is a landmark development in the lifelong monitoring and international comparison of education (Grek, Citation2010) which draws together new social actors and discourses. The first round of the survey compared performance in literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology-rich environments among adults aged 16–65 years, across 24 countries. The second round surveyed a further 9 countries. PIAAC is an interesting case since compared with surveys such as PISA and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) that focus on children in school, the space of adult lifelong learning is less well defined. It crosses education, employment and citizenship domains, each with their own competing discourses and struggles for visibility in the public sphere. From this perspective, PIAAC has a ‘plasticity’ that, as Carvalho (Citation2012) points out, can offer flexible possibilities for the translation of widely varying interests into a common project, engaging new publics who can, in turn, mobilise governments. However, the lack of clear definition of this field also leaves it especially vulnerable to the manipulation of various interest groups, or to being completely ignored by the media and policy actors.

For this occasion, the OECD provided in advance a press release explaining when and for which countries results would be released together with details of the in-country agencies involved and planned media events. It also publicised ahead a webinar organised on the release date of 28 June at which Andreas Schleicher spoke. The recording of this is now available on YoutubeFootnote1 and the slides on Slideshare.Footnote2

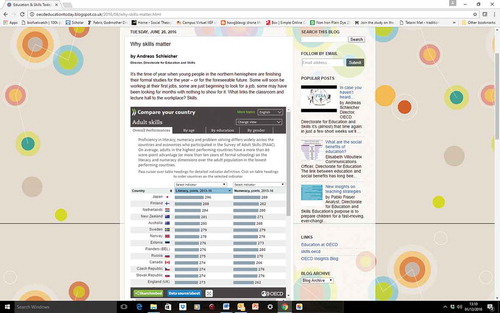

The embargoed report was released on the previous day to registered journalists and, on the day itself, the report and country notes were available online from the OECD website, together with a further press releaseFootnote3 outlining the findings and a blog written by Schleicher that included an interactive statistical section so that countries could compare aspects of their own results with other countries of their choice (see ).

Figure 1. Screenshot of interactive statistics on OECD blog site Schleicher (Citation2016).

Schleicher’s presentation in the webinar focused on Singapore as an example country and used the pattern of results to make comparisons with other countries, for example, in terms of age trends. He argued skilfully that although Singapore overall did not come out top of the league tables, the younger age groups are high-performing and this is the result of an excellent education system developed in recent years. He thereby positioned it as a motivational success story for less economically developed countries to emulate.

From a wealth of potential evidence, he draws attention to selected figures: the age differences in achievement, the overall country average compared with the OECD average and the degree of inequality as shown by the in-country distribution of high and low achievers. This is supplemented for some countries by mention of gender/ethnic minority differences.

The OECD materials and presentations are aimed not only at media professionals but also a larger audience of already interested experts and advocates and are straightforward in their expression of the core features of the survey. Such materials are crucial links in the discursive chain framing the findings. They are carefully crafted, timed and targeted, and essential for understanding the subsequent media coverage and how public opinion is formed in relation to ILSAs.

These OECD materials and events are linked directly to the agency’s own site but they are also circulated and recycled in national contexts. For example, in June 2016, while the U.K. national newspapers were preoccupied with the European referendum results and did not cover PIAAC second round findings, the BBC online posted an article written by Schleicher repeating the arguments developed during the OECD webinar.Footnote4

Hamilton (Citation2016) identifies a number of strong assumptions that underlie communications from the testing agencies and the whole enterprise of international testing of adult skills. These are unstated but powerful in shaping our common-sense understanding of the topic. Firstly, the PIAAC is based on an imagined future envisioned by techno experts (Ozga et al., Citation2011). Skills are defined as individual performances of information processing, based in cognitive psychometric theory. This removes them from the relational, situated practices of which they are a part and comparisons proceed along a single dimension for each measured skill, implying a universal, decontextualised curriculum (Sellar & Lingard, Citation2015). Secondly, skills are defined as economic and work-related while other dimensions of social life are rendered less visible. Thirdly, the public are invited to imagine the global world as composed of nation states as the unit of comparison and policy advice, although there are other plausible ways, for example, units based on common languages, ethnic or religious groupings or even an economic map composed of rich and poor, and the distribution and/or control of economic resources by corporations or governments.

This competitive, technological model of skills is reiterated in numerous other communications and in promoting it the OECD creates what Law (Citation2011) describes as ‘collateral realities’. These are realities that get done incidentally, along the way and become part of our naturalised, common sense understandings. A particular view of the nature of ‘real’ evidence – aggregated rather than situated – is asserted and valorised, while historical and contextual comparison is overshadowed.

The case of PIAAC also reveals new strategies being developed by testing agencies, advocacy groups and the media industry which are designed to create better-informed publics. Aware of the special demands that complex, large-scale data sets make on journalists, and the difficulties of presenting these within the very tight time constraints of their work, some national governments are working with journalists to prepare them for the release of survey findings. For example, the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, a government advocacy agency, offers training and orientation to the PIAAC surveys ahead of the release of the results (Javrh, Citation2016).

In a parallel development, both the OECD and the IEA now offer statistical training workshops to induct specialist researchers in participating countries to the data procedures and the software needed to carry out further analysis of survey findings. O’Keeffe (Citation2015) analyses these events and shows how such interventions generate significant discursive effects while shaping academic understanding and responses to ILSAs. These new strategies, training those who mediate ILSA results to the academic community and the general public, offer new routes for influence and expertise which it is important to monitor.

Issues in reporting and interpreting findings in the media

This section reviews a range of recent studies that contribute to our understanding of how ILSA findings are actually reported and interpreted by the news media. These have been chosen to illustrate a set of key issues involved in theorising how survey findings are translated into public discourse and policy debates in national contexts.

One caution should be noted: most empirical media research in this area to date has focused on print newspapers simply because comprehensive and accessible databases exist. However, survey findings are now publicised across the full range of available interlinked media platforms – newspapers, broadcast media, online news sites, videos and social media, especially Twitter, so an urgent agenda is to study these sites more fully as it becomes easier to extract data from them.

A first issue concerns the range of presentational formats that have been developed to communicate the findings, including narrative text and visualisations of the numerical findings through still and moving images, tables and diagrams (See Hamilton, Citation2012; Stack, Citation2013; Williamson, Citation2016). Recent literature has focused on the communicative power and logic of numbers to encode and classify information in particular ways and to enable precise relationships among variable categories to be explored. O’Halloran (Citation2005) goes further to discuss how the different modes of language, image and number act in combination to enhance communicative power. Her insights are increasingly relevant as interactive digital displays are developed using sophisticated infographic software.Footnote5 These displays are based on numerical data but enable audiences to bypass the numbers themselves and interpret the underlying figures through patterned symbolic elements of space, colour and sound such as a colour-coded map overlaid with stylised people and flags. While agencies like the OECD use these displays in their online communications (see ), technical consultants and data journalists appear to be enthusiastically developing the most alluring versions (see for example, Buchta, Citation2013; Knight, Citation2015; Lundahl, Citation2016; Rogers, Citation2016; on the ‘aesthetics of numbers’).

Figure 2. Screenshot from OECD video displaying the PIAAC round 2 findings across countries [http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/].

![Figure 2. Screenshot from OECD video displaying the PIAAC round 2 findings across countries [http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/].](/cms/asset/71bc92df-75f9-4829-adf6-dee7111d7bff/rcse_a_1330761_f0002_oc.jpg)

A second issue is the degree to which the media influence policy narratives by selectively or critically engaging with the findings. Rubenson and Walker (Citation2014) found the Canadian media to be very influential in pushing public opinion about adult literacy and even instrumental in the development of the IALS. However, most studies suggest a more ambivalent role for the media. Several have found that reports of the ILSA results closely follow press releases and other guidance from testing agencies with little critical engagement from journalists (e.g. Pons, Citation2011; Stack, Citation2006; Yasukawa et al., Citation2016). Debate focuses around policy options rather than challenging the validity of the findings themselves and is framed by national contexts (Baroutsis & Lingard, Citation2017). This allows not only the testing agencies but also national politicians and other interested groups to manage the interpretation of the findings, pushing the public discourse in particular directions.

Yasukawa et al. (Citation2016) found that aspects of PIAAC survey findings showcased in the OECD country notes were accepted as unquestioned facts and reproduced prominently in press articles. However, these were still presented selectively in ways that fitted existing national policy narratives and debates. Age differences in test results generated great interest, while within-country inequalities according to socio-economic background, gender or ethnicity were more variably mentioned and interpreted in the light of recent national educational reforms. Elstad (Citation2012) examined the media coverage of PISA in Norway over several years and identified strategies of ‘blame shifting and avoidance’ among the implicated political actors; Her paper demonstrates that the media can play a central role in terms of the preoccupations of politicians to appear in a good light within public debates.

The idiosyncratic features of national educational systems can also affect the ways in which ILSAs are reported and the policy response to them as Lewis and Lingard (this issue) discuss in their comparison of the effects of PISA on the different federal systems in Australia and the U.S. (and see also Carvalho & Costa, Citation2015). Green Saraisky (Citation2015) concludes for the U.S. that despite widespread coverage of the PISA findings and acceptance of the survey in the public discourse, policy is still driven by political priorities rather than the rationalities of empirical data. Her work demonstrates the profoundly pragmatic nature of much policy action which often uses a veneer of evidence to justify decisions made elsewhere.

A third issue is that international rankings encourage countries to compare themselves externally with other ‘reference societies’ and these are reported both positively and negatively in the media, frequently drawing on dubious stereotyping. Certain high-scoring countries such as Finland become a magnet for emulation and analysis (Takayama, Waldow, & Sung, Citation2013). The top performing Asian countries, such as Korea and Singapore, and most recently Shanghai (Sellar & Lingard, Citation2013a) are, however, discussed more ambivalently with reference to a perceived lack of creativity and high student stress that results from the intense study regimes built into educational systems in these countries (Waldow, Takayama, & Sung, Citation2014).

Green Saraisky (Citation2015), Yasukawa et al. (Citation2016) and others raise the further issue that a narrow and predominantly elite range of people are invited to comment in media reports. It is rare for the voices of parents, teachers or students to surface. There have been energetic parent/teacher-led campaigns in the U.S. and elsewhere against national testing but little of this has spilled over to ILSAs. Even academic commentary is infrequent in the national press, especially where it might disrupt the narratives offered by testing agencies and national government actors. A notable counter example is the widely circulated open letter to Andreas Schleicher published in the U.K. Press. This was signed by a large number of academics and provoked a response from the OECD (Meyer, Zahedi, & signatories, Citation2014). The development of respected online specialist academic media (such as the Conversation) may offer new spaces for debate as experts on ILSAs are given advanced access to reports and invited to write opinion pieces.

A final issue concerns the timing of the release and coverage of ILSA findings and the importance of taking a longer perspective on media responses. International surveys have to compete with other news stories and at a given moment, the media may ignore the findings altogether, or give sparse and fleeting coverage. In these cases, policy outcomes may also be negligible as, for example, for PIAAC in Canada (Clair, Citation2016), Denmark (Cort & Larson, Citation2015, Citation2016) and the U.K. (Yasukawa et al., Citation2016). Mons et al. (Citation2009) show how the media coverage and public awareness of PISA in France grew over time from feeble beginnings and was related to wider policy interests that entered the public debates.

Conclusions

Existing research into the diffusion of ILSA findings into national contexts offers no simple answer to the question of how these are translated into policy reforms. It does, however, provide important insights into the factors at play and the potential role of the media. Interested parties and publics addressed by the ILSAs emerge to actively manage the interpretation and circulation of survey results according to their own goals and priorities. Thus, even where the media coverage is substantial, interpretations of the findings and policy uptake are uncertain, ‘Success’ in the sense of tangible policy reform is not guaranteed.

The high status accorded to statistical expertise which is not available to ordinary citizens has its own logic and momentum. Lay publics are rendered incompetent by ILSAs and the complex survey data that have to be conveyed to them are seen to require translation into simpler, easy to understand content and forms. Specialised journalist and researcher training is developing to meet the demands of datification of policy and public discourse and is part of a spreading discourse of expertise with numbers to new sites.

In some cases, as shown above, ILSAs fail to gain the attention of either the public or policymakers at all. Reports about skills and education rarely hit the front pages of national newspapers and can easily be sidelined by more newsworthy stories. This makes the popularisation of PISA within public discourse a notable achievement though as Mons et al. (Citation2009) show, even this has taken time to build.

Researching the detail of the politics and processes of national engagements with ILSA findings thus offers an important brake on the idea that the very existence of ILSAs has a totalising effect on national policy. The rational evidence-based approach to policy that underpins the strategies of international agencies is only one way of conceptualising the dynamic of public discourse and change. The reality is frequently much more subtle and complex.

This paper nevertheless argues that ILSAs shape our apprehension of educational achievement at much more profound and ubiquitous level. As Berényi and Neumann (Citation2009, p. 50) conclude from their study in Hungary, PISA has become ‘a master narrative for domestic education policy’ despite a lack of tangible reform within the country.

There is little evidence of any successful attempts to challenge and break apart the ILSA assemblage by shifting the value basis and terms of the debates about the measures themselves. A limited range of voices is heard in the mainstream media and academic critiques are easily absorbed as merely technical matters. Grass roots campaigns by teachers and parents resisting the use of standardised tests can be hard to sustain in the face of the well-resourced media management of international agencies. These limitations on critical action are well summed up by Pons (Citation2012) who argues that many countries lack a ‘space of translation’ in which a wider range of actors can be enrolled to discuss and produce a more considered response to ILSAs of the sort advocated by Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe (Citation2009).

The analysis offered here shows how ILSAs can affect the educational environments they enter, regardless of whether measured outcomes of student learning improve. These effects (Law’s ‘collateral realities’) are produced along the way as publics and institutions learn to think about and compare their achievements in particular domains. In doing so, they channel political and policy imagination and action. The media and public discourses are entangled in this process which may ‘disorganise’ (Hassard, Kelemen, & Cox, Citation2012) existing education systems in unintended ways as much as reform them along the recommended lines of international agencies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mary Hamilton

Mary Hamilton is Professor Emerita of Adult Learning and Literacy in the Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University, UK and a Director of the Laboratory for International Assessment Studies. She carries out historical and interpretative policy analyses exploring how international influences reach into local practice and the implications of this for tutor and student agency in literacy education. She has published in the areas of literacy policy and governance, socio-material theory, academic Literacies, digital technologies and change. She is currently involved in a comparative study of media coverage of the PIAAC survey findings and is especially interested in the rise of data journalism and the use of multiple modes of communication to publicise the findings, including numbers and visualisations.

Notes

2 https://www.slideshare.net/OECDEDU/why-skills-matter-further-results-from-the-survey-of-adult-skills

5 See for example Seattle based software company Tableau http://www.tableau.com/

References

- Addey, C., & Sellar, S. (2017). Why do countries participate in PISA? Understanding the role of international large-scale assessments in global education policy. In A. Verger, M. Novelli, & H. K. Altinyelken (Eds.), Global education policy and international development: New agendas, issues and policies (2nd ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Addy, C. (2015). Participating in international literacy assessments in Lao PDR and Mongolia: A global ritual of belonging. In M. Hamilton, B. Maddox, & C. Addey (Eds.), Literacy as numbers: Researching the politics and practices of international literacy assessment (pp. 147–164). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baroutsis, A., & Lingard, B. (2017). Counting and comparing school performance: An analysis of media coverage of PISA in Australia, 2000–2014. Journal of Education Policy, 32(4), 432–449.

- Berényi, E., & Neumann, E. (2009). Grappling with PISA. Reception and translation in the Hungarian policy discourse. Sísifo, 10, 41–52.

- Blackmore, J., & Thorpe, S. (2003). Media/ting change: The print media’s role in mediating education policy in a period of radical reform in Victoria, Australia. Journal of Education Policy, 18(6), 577–595. doi:10.1080/0268093032000145854

- Bolívar, A. (2011). The dissatisfaction of the losers. In M. A. Pereyra, H. G. Kotthoff, & R. Cowen (Eds.), PISA under examination (pp. 61–74). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Buchta, H. (2013). OECD PIAAC Study 2013 data available for analysis. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://ms-olap.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/oecd-piaac-study-2013-data-available_10.html

- Callon, M., Lascoumes, P., & Barthe, Y. (2009). Acting in an uncertain world. An essay on technological democracy. MIT Press.

- Carvalho, L. M. (2012). The fabrications and travels of a knowledge-policy instrument. European Educational Research Journal, 11(2), 172–188.

- Carvalho, L. M., & Costa, E. (2015). Seeing education with one’s own eyes and through PISA lenses: Considerations of the reception of PISA in European countries. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(5), 638–646.

- Chouliaraki, L., & Fairclough, N. (1999). Discourse in late modernity: Rethinking critical discourse analysis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Clair, R. S. (2016). Plus ça change–The failure of PIAAC to drive evidence-based policy in Canada. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung-Report, 39(2), 225–239. doi:10.1007/s40955-016-0070-0

- Colmant, M. (2007). The impact of PIRLS in France. In K. Schwippert (Ed.), Progress in reading literacy. Munich: Verlag.

- Cort, P., & Larson, A. (2015). The non-shock of PIAAC - Tracing the discursive effects of PIAAC in Denmark. European Educational Research Journal, 14(6), 531–548. doi:10.1177/1474904115611677

- Cort, P., & Larson, A. (2016, September). In the aftermath of the Danish PIAAC results: A transnational technology of governance without consequence? Presentation to the ESREA Conference, Maynooth.

- Elstad, E. (2012). PISA debates and blame management among the Norwegian educational authorities: Press coverage and debate intensity in the newspapers. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 48, 10–22.

- Fairclough, N. (2000). New labour, new language?. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Fenwick, T., Edwards, R., & Sawchuk, P. (2015). Emerging approaches to educational research: Tracing the socio-material. London: Routledge.

- Gorur, R. (2011). ANT on the PISA trail: Following the statistical pursuit of certainty. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 43(s1), 76–93. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2009.00612.x

- Green Saraisky, N. (2015) The politics of international large-scale assessment: The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and American education discourse, 2000-2012 ( PhD). Columbia University. doi:10.7916/D8DB80WW

- Grek, S. (2008). PISA in the British media: Leaning tower or robust testing tool? Centre for Educational Sociology, Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

- Grek, S. (2010). International organisations and the shared construction of policy ‘problems’: Problematisation and change in education governance in Europe. European Educational Research Journal, 9(3), 396–406. doi:10.2304/eerj.2010.9.3.396

- Hamilton, M. (2012). Literacy and the politics of representation. London: Routledge.

- Hamilton, M. (2016, September) The discourses of PIAAC: Re-imagining literacy through numbers. Paper presented at the ESREA conference, Maynooth.

- Hamilton, M., & Pitt, K. (2011). Challenging representations: Constructing the adult literacy learner over 30 years of policy and practice in the United Kingdom. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(4), 350–373. doi:10.1002/rrq.2011.46.issue-4

- Hassard, J., Kelemen, M., & Cox, J. W. (2012). Disorganization theory: Explorations in alternative organizational analysis. London: Routledge.

- Javrh, P. (2016, April). How to work with media and policy makers. Presentation at ESRC seminar on the politics of reception, Lancaster. Retrieved May 7, 2017, from, https://youtu.be/6CWj8AF6Eeg

- Knight, M. (2015). Data journalism in the UK: A preliminary analysis of form and content. Journal of Media Practice, 16(1), 55–72. doi:10.1080/14682753.2015.1015801

- Law, J. (2011). Collateral Realities. In F.D. Rubio, and P. Baert (Eds.) The Politics of Knowledge (pp. 56–178). London: Routledge.

- Lewis, S., & Hardy, I. (2015). Funding, reputation and targets: The discursive logics of high-stakes testing. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(2), 245–264. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2014.936826

- Lewis, S., & Lingard, B. (forthcoming) Placing PISA and PISA for Schools in two federalisms, Australia and the USA.

- Lingard, B. (2016). Rationales for and reception of the OECD’s PISA. Educação & Sociedade, 37(136), 609–627. doi:10.1590/es0101-73302016166670

- Lingard, B., & Sellar, S. (2013). ‘Catalyst data’: Perverse systemic effects of audit and accountability in Australian schooling. Journal of Education Policy, 28(5), 634–656. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.758815

- Lundahl, C. (2016). The aesthetics of numbers, the beauty of PISA laboratory for international assessments studies blog post. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from, http://international-assessments.org/the-aesthetics-of-numbers-the-beauty-of-pisa/

- Lundby, K. (2009). Mediatization: Concept, changes, consequences. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Meyer, H. D., & Benavot, A. (Eds.). (2013). PISA, power, and policy: The emergence of global educational governance. Providence, RI: Symposium Books Ltd

- Meyer, H. D., Zahedi, K., & signatories. (2014). An open letter: To andreas schleicher, OECD, Paris 5th May. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/may/06/oecd-pisa-tests-damaging-education-academics

- Mons, N., Pons, X., Van Zanten, A., & Pouille, J. 2009. The reception of PISA in France. Connaissance et régulation du système éducatif. Paris: OSC.

- Morgan, C. (2007). OECD programme for international student assessment: Unraveling a knowledge network. ProQuest. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?user=cSuiBH4AAAAJ&hl=en&oi=sra

- O’Connell, C. (2015). An examination of global university rankings as a new mechanism influencing mission differentiation: The UK context. Tertiary Education and Management, 21(2), 111–126. doi:10.1080/13583883.2015.1017832

- O’Halloran, K. (2005). Mathematical discourse: Language, symbolism and visual images. London: Continuum.

- O’Keeffe, C. (2015) Assembling the adult learner: Global and local e-assessment practices’ ( Unpublished thesis). Lancaster University.

- Ozga, J., Dahler-Larsen, P., Segerholm, C., & Simola, H. (Eds.). (2011). Fabricating quality in education: Data and governance in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Pidd, M. (2005). Perversity in public service performance measurement. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 54(5/6), 482–493. doi:10.1108/17410400510604601

- Pons, X. (2011). What do we really learn from PISA? The sociology of its reception in three European countries (2001–2008) 1. European Journal of Education, 46(4), 540–548. doi:10.1111/ejed.2011.46.issue-4

- Pons, X. (2012). Going beyond the ‘PISA shock’ discourse: An analysis of the cognitive reception of PISA in six European countries, 2001–2008. European Educational Research Journal, 11(2), 206–226. doi:10.2304/eerj.2012.11.2.206

- Rawolle, S. (2010). Understanding the mediatisation of educational policy as practice. Critical Studies in Education, 51(1), 21–39. doi:10.1080/17508480903450208

- Richardson, S., & Coates, H. (2014). Essential foundations for establishing equivalence in cross-national higher education assessment. Higher Education, 68(6), 825–836. doi:10.1007/s10734-014-9746-9

- Rogers, S. (2016). Data journalism matters more now than ever before. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://simonrogers.net/2016/03/07/data-journalism-matters-more-now-than-ever-before/

- Rubenson, K., & Walker, J. (2014). The media construction of an adult literacy agenda in Canada. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 12(1), 141–163.

- Schleicher, A. (2008). PIAAC: A new strategy for assessing adult competencies. International Review of Education, 54(5–6), 627–650. doi:10.1007/s11159-008-9105-0

- Schleicher, A. (2016). Why skills matter. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://oecdeducationtoday.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/why-skills-matter.html

- Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2013a). Looking East: Shanghai, PISA 2009 and the reconstitution of reference societies in the global education policy field. Comparative Education, 49(4), 464–485. doi:10.1080/03050068.2013.770943

- Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2013b). PISA and the expanding role of the OECD in global educational governance. In H. D. Meyer & A. Benavot (Eds.), PISA, power, and policy: The emergence of global educational governance (pp. 185–206). Providence, RI: Symposium Books Ltd.

- Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2015). New literacisation, curricular isomorphism and the OECD’s PISA. In M. Hamilton, B. Maddox, & C. Addey (Eds.), Literacy as numbers: Researching the politics and practices of international literacy assessment (pp. 17–34). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (2015). Audit culture revisited. Current Anthropology, 56(3), 421–444. doi:10.1086/681534

- Stack, M. (2006). Testing, testing, read all about it: Canadian press coverage of the PISA results. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de L’éducation, 29, 49–69. doi:10.2307/20054146

- Stack, M. (2016). Global University rankings and the mediatization of higher education. New York: Springer.

- Stack, M. L. (2013). The times higher education ranking product: Visualising excellence through media. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 11(4), 560–582. doi:10.1080/14767724.2013.856701

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2003). The politics of league tables. Journal of Social Science Education, 2(1). http://www.jsse.org/index.php/jsse/article/view/470

- Takayama, K., Waldow, F., & Sung, Y.-K. (2013). Finland has it all? Examining the media accentuation of “Finnish education” in Australia, Germany, and South Korea. Research in Comparative and International Education, 8(3), 307–325. doi:10.2304/rcie

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice: New tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Waldow, F., Takayama, K., & Sung, Y.-K. (2014). Rethinking the pattern of external policy referencing: Media discourses over the “Asian Tigers’” PISA success in Australia, Germany, and South Korea. Comparative Education, 50(3), 302–321. doi:10.1080/03050068.2013.860704

- Williamson, B. (2016). Digital education governance: Data visualization, predictive analytics, and ‘real-time’ policy instruments. Journal of Education Policy, 31(2), 123–141.

- Yasukawa, K., Hamilton, M., & Evans, J. (2016). A comparative analysis of national media responses to the OECD survey of adult skills: Policy making from the global to the local? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(2), 271–285.