Watanabe and Tatsuno [Citation1] in their state-of-the-art review on omega-3 fatty acids for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases commented that the effects of omega-3 fatty acids on the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) have not been established. However, the Long-Term Outcomes Study to Assess Statin Residual Risk with Epanova in High Cardiovascular Risk Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia (STRENGTH) double-blind, randomized trial [Citation2] though demonstrated no significant reduction in the primary endpoint consisting of a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization, among patients treated with omega–3 carboxylic acids (CA) versus patients treated with corn oil (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.99 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–1.09), but there was an increased risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in the omega-3 CA group compared with the corn oil group (HR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.29–2.21). Indeed, this was one of the reasons for the early termination of the STRENGTH trial. The detection of an increased risk of AF was not unique to the STRENGTH trial. The previous Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention (REDUCE-IT) double-blind, randomized trial [Citation3] reported that the endpoint of hospitalization for AF or flutter occurred more frequently in patients randomized to icosapent ethyl (highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester) than placebo (3.1% vs. 2.1%, P = 0.004). While Watanabe and Tatsuno [Citation1] commented that a definitive conclusion cannot be drawn at this stage due to the variation across the available trials, but we believe there are adequate large-scale randomized controlled trials for us to perform a meta-analysis to summarize the existing evidence on the overall effect of omega-3 fatty acids on the development of AF.

Two investigators (CSK and SSH) performed a systematic literature search in electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for randomized controlled trials that reported new-onset incident/recurrent AF following exposure to omega-3 fatty acids. We used the following keywords for our literature search: ‘atrial fibrillation’ and ‘omega-3’. The search was limited to studies published in the English language and performed in human participants. Study abstracts were screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria included randomized controlled trials comparing the use of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation and containing eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) alone or EPA plus docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) versus control, a sample size of 500 participants or more, and reported new-onset incident/recurrent AF following exposure to omega-3 fatty acids. We excluded non-randomized trials, observational studies, and trials with less than 1 year of follow-up duration. Two investigators independently extracted the following data from the included trials: number of participants, demographics of participants,, the dose of omega-3 fatty acids, the incidence of new-onset/recurrent AF, and duration of follow-up. The meta-analysis was performed by computing the incident rate ratio for the incidence of new-onset/recurrent AF using both the random-effects model and inverse variance heterogeneity (IVhet) model along with 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity across included trials was assessed with Cochran’s Q method with I2 statistics to evaluate the magnitude of the heterogeneity across studies. We also conducted subgroup analysis stratified by the dose of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation (high-dose [>1 g/day EPA or EPA + DHA] and low-dose [≤1 g/day EPA or EPA + DHA]). Two investigators (CSK and SSH) assessed the risk of bias of the trials included with Version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [Citation4], which is a standardized method for assessing potential bias in reports of randomized interventions. RoB 2 is structured into a fixed set of domains of bias, focusing on different aspects of trial design, conduct, and reporting. A proposed judgment about the risk of bias arising from each domain is generated by an algorithm, where judgment can be ‘Low’ or ‘High’ risk of bias or can express ‘Some concerns’. All analyses were performed using Meta XL, version 5.3 (EpiGear International, Queensland, Australia).

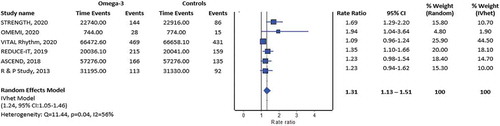

Our initial search retrieved 510 titles; upon removal of duplicated records, a total of 315 full-text articles were identified for detailed assessment; 6 randomized controlled trials were ultimately included in our systematic review and meta–analysis. [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5–8] Our data synthesis included 75,120 patients who were predominantly male (60%) with a mean age of 65.8 years. Characteristics of the included trials are presented in . All trials were published between the years 2013 and 2020 [Citation1,Citation2,Citation4–7]. Three trials each employed high-dose [Citation2,Citation3,Citation8] and low-dose [Citation5–7] regimen of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation. Except for the OMega–3 fatty acids in Elderly patients with Myocardial Infarction (OMEMI) trial [Citation8] which had some concerns regarding the overall risk of bias (some concerns related to the risk of bias from missing outcome data), the other five trials had an overall low risk of bias [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5–7]. The estimated effect of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on the risk of AF indicated a significantly increased risk (incident rate ratio = 1.31; 95% confidence interval: 1.13–1.51 (RE model, ); incident rate ratio = 1.24; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.05–1.46) (IVhet model, ), with adequate evidence against our model hypothesis of no significant difference at the current sample size. In the subgroup analysis stratified by the dose of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation, both the use of high-dose omega-3 fatty acids supplementation (Figure S1; incident rate ratio = 1.51; 95% CI: 1.26–1.81) and low-dose omega-3 fatty acids supplementation (Figure S2; incident rate ratio = 1.14; 95% CI: 1.03–1.27) were similarly associated with a significantly increased risk of AF.

Figure 1. Pooled incident rate ratio for atrial fibrillation across randomized controlled trials between the patients exposed and unexposed to omega-3 fatty acids

Table 1. Characteristics of included randomized controlled trials

The findings for a relatively increased risk of AF in patients receiving omega-3 fatty acids supplementation are unexpected since omega-3s have been purported to possess antiarrhythmic effects with the ‘Andersen membrane spring-like tension hypothesis’, in which omega-3s could reduce the conductance of ion channels [Citation9]. Interestingly, while a Danish cohort study [Citation10] with 57,053 participants revealed a U-shaped association between the amount of consumption of marine omega-3 fatty acids per day and risk of incident AF, such association was not replicated in the randomized controlled trials. We believe the further evaluation of the underlying mechanisms for an increased risk of AF with omega-3 fatty acids supplementation is warranted with the widespread use of omega-3 fatty acids supplements globally. In addition, except the VITAL Rhythm trial [Citation5], all the other included trials [Citation2,Citation3,Citation6–8] were performed in a high-risk cohort, i.e. those at high cardiovascular risk or with established cardiovascular disease, and therefore the association may not apply to healthy individuals receiving high-dose or low-dose omega-3 fatty acids. This could bring significant confounding bias that may result in an over- or underestimation of the observed association between omega-3 fatty acids and increased risk of AF. While the absolute increased risk of AF is rather small, clinicians should consider both the benefits and risks of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in a particular patient, especially one with a prior history of AF.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.1 KB)Acknowledgments

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Watanabe Y, Tatsuno I. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids focusing on eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: a review of the state-of-the-art. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14(1):79–93.

- Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, Garcia M, et al. Effect of high-dose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: the STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2268.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):11–22.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- Albert CM, Cook NR, Pester J, et al. Effect of marine omega-3 fatty acid and vitamin D supplementation on incident atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1061–1073.

- Risk and Prevention Study Collaborative Group, Roncaglioni MC, Tombesi M, Avanzini F, et al. n-3 fatty acids in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2013 May 30;368(22):2146]. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1800–1808.

- ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al. Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2018;379(16):1540–1550.

- Kalstad AA, Myhre PL, Laake K, et al. Effects of n-3 fatty acid supplements in elderly patients after myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov 15]. Circulation. 2020;143(6):528–539.

- Leaf A, Xiao YF, Kang JX, et al. Prevention of sudden cardiac death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98(3):355–377.

- Rix TA, Joensen AM, Riahi S, et al. A U-shaped association between consumption of marine n-3 fatty acids and development of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter-a Danish cohort study. Europace. 2014;16(11):1554–1561.