ABSTRACT

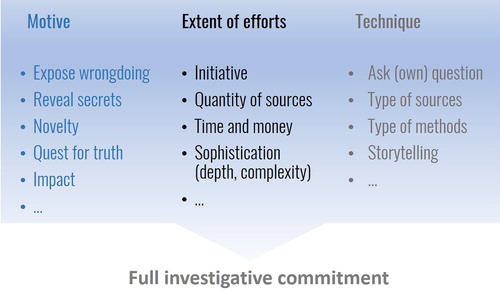

This paper examines how professionals define investigative journalism, which criteria they use to assess their and others’ work, and how they apply them. Based on 23 in-depth interviews with Swiss journalists, our research sheds new light on professionals’ normative assumptions, and provides insights on how to think about investigative journalism more generally. Implicit and explicit professional definitions reveal a shared conception of journalism, which has strong normative implications. According to their narratives, professionals rely on a gradual and multilevel definition of investigative journalism, while often talking about it as an absolute. Rather than a discrete category, “investigative journalism” is best seen as existing on a continuum between full-fledged investigative endeavor and the most basic reporting, with the main cursor being the personal commitment: professionals value the extent of efforts provided during the investigative process, as much as other constitutive elements such as exposing breaches of public trust. They built on a mix of various elements regarding what constitutes investigative journalism. We distinguished three types of defining criteria: motive, extent of efforts and technique involved. These criteria counterbalance each other in practice. Arguably, these gradual conceptions allow for adjustments between a clear-cut ideal and the real work context.

Introduction

Journalism is arguably undergoing profound reconfigurations in a context often deemed hostile or at least increasingly difficult. The erosion of audiences for journalistic information has been affecting all traditional media. Economic considerations are reshaping managerial and editorial decisions. There are numerous signs of public mistrust of the media. And, finally, journalism is experiencing an identity crisis resulting from new technologies and its loss of monopoly on information and communication (Donsbach Citation2009). Following other less techno-economical perspectives, journalism's crises are better understood as cultural expressions of shifting values, discourses and practices (Alexander Citation2016). Whatever the causes behind the crises of journalism, investigative journalism appears as a promising field for renewal or evolution of journalism.

The watchdog role of journalism—investigative reporting—is adapting to its austere media environment. It is enduring, even thriving, in the digital age. […] It is in better shape than other forms of journalism because of its value to corporate branding and/or the public interest. Evidence-based investigative reporting re-establishes its publishers as quality media outlets in the digital age—when competition for attention is fierce—by offering unique public interest stories for which audiences are prepared to pay. (Carson Citation2019b)

Despite its public visibility, investigative journalism is surrounded by definitional uncertainty, while its myths are enhanced by international leaks and fiction. Defining what constitutes investigative journalism remains a challenge: be it a journalistic genre, the practices of a specific subgroup of professionals, a marketing strategy or a professional ideal, there are several conceptions of investigative reporting and a variety of practices (Charon Citation2003; Bromley Citation2005; De Burgh Citation2008; Carson Citation2019a, 54). This is a highly normative debate that this study doesn't aim to resolve, because it refers to several framings, traditions and contexts (Labarthe Citation2018). Rather, we aim to analyze what conceptions of investigative journalism drive professional journalists, in order to provide insights on how to better study watchdog journalism.

The swiss information media landscape makes for an interesting field of observation. Journalism there is strongly professionalized, self-regulated and in the grip of media concentration. While it encompasses distinct linguistic and journalistic subcultures alongside a strong vivacity of the press (Bonfadelli et al. Citation2011; Dingerkus et al. Citation2018), it is an engaging illustration of the North-European media system, a “democratic corporatist model” following Hallin and Mancini's classification (Citation2004). This means that Swiss journalists enjoy relative autonomy in the exercise of their profession with a strong protection of press freedom, similar to the situation in Germany, Belgium, or in the Scandinavian countries (press subsidies apart). The way investigative journalists experience their craft and their professional identity in Switzerland is therefore likely comparable to the overall context of North European countries. Furthermore, previous research has also shown that Swiss journalists were similar to their peers in the global North (including France, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, United States and Australia) in terms of work conditions and role perceptions (Bonfadelli et al. Citation2011; Hanitzsch et al. Citation2011; Bonin et al. Citation2017).

Yet, academic research about watchdog reporters has largely focused on North Atlantic countries, mainly the United states where investigative journalism is strongly developed (Ettema and Glasser Citation1998; Hallin and Mancini Citation2004, 233; Kaplan Citation2008; Carson Citation2019a). In the past twenty years, Europe has become an important venue for the development of investigative reporting, with the recent spread of nonprofit structures (Baggi Citation2011) and national or cross-border networks. Only few studies have been published about European investigative journalists however, notably a report of the Dutch professional network VVOJ (van Eijk Citation2005) and more recent PhD works (e.g. Descamps Citation2017; Labarthe Citation2019a).

Building on Swiss professionals’ narratives, this paper tries to contribute to this expanding field. It aims at understanding how investigative journalism takes shape by analyzing and comparing explicit and implicit professional discourses in the Swiss media landscape, based on 23 in-depths interviews with what can be called watchdog reporters.

Thus, our research questions focused on the particularities of such journalists, their conceptions of investigative journalism, and their insights into their own practice: how they define investigative journalism, which criteria they use to assess their and other's work, and how they apply them.

The paper first develops on the main concepts related to our research question, and describes the methodology used. Followed by a presentation and discussion of our results in two parts. First, we outline our two main observations, namely that respondents share an ideal conception of journalism, while experiencing difficulties in defining and theorizing work processes that appear natural and instinctive to them. When it comes to defining investigative journalism, journalists show forms of reluctance, which can be explained both by the difficulty of defining a vague object and by the “refusal” to make it a specific category of journalism. We relate this to the widespread perception that investigative journalism is not just another form but the very essence of journalism. The unity of the field of journalism is also at stakes.

Second, we develop on the fact that professionals rely on a gradual and multilevel definition, while experiencing investigative journalism as a clear-cut category at the same time. Respondents show flexibility in their discourses about what constitutes investigative work when assessing their own practice and their peers. This suggests a continuum between a full-fledged investigative endeavor and the most basic reporting, with the main cursor being the personal commitment and the extent of efforts provided during the investigative process. A range of other parameters, namely the degree of revelation, the extent of exposed wrongdoing and so on, takes shape on this continuum. We describe them and argue that they allow journalists to make adjustments between their ideals and their practice.

Definition of Investigative Journalism

There is no unanimity on the definition of investigative journalism, either in the scientific literature or among practitioners. At the very least, academics and professionals agree to see it as an enthusiastic way to practice conventional reporting to the full extent of its potential: a “critical and in-depth journalism” (van Eijk Citation2005, 12). It is considered the “most active” form of reporting, following McQuail's continuum of journalistic activity—the continuum of initiative and activity (Citation2013, 104). This means that investigative reporting, more than any other forms of journalism, supposes a lot of personal commitment from the reporters. The idea of commitment is interesting as it allows for a complex but functional definition to make sense of a vague concept, as we will see in the following.

Several scholars note that investigative journalism is a challenge to define, as it entails a lot of different things, ranging from a particular cast of experienced journalists in a particular context, to a specific genre, not to mention its mythical nature (Marchetti Citation2002; Charon Citation2003; Bromley Citation2005; De Burgh Citation2008; Harcup Citation2015; Carson Citation2019a). In France, for instance, it previously referred to a certain type of journalism—also known as “journalism des affaires” (Marchetti Citation2002; Charon Citation2003). In the United States, on the other hand, it reflects an evolution of journalism focused on exposing wrongdoing, inherited from the muckrakers and based on a methodology that took off in the post-Watergate period (Hunter Citation1997; De Burgh Citation2008). “Over time it has been described in various ways: watchdog or reform journalism, muckracking or exposure reporting, the fourth estate, detective reporting, adversarial journalism, advocacy reporting, public interest journalism and campaign journalism”, notes Carson (Citation2019a).

Among scholars and journalists (Protess Citation1991; De Burgh Citation2008, 13; Hunter Citation2011; Plenel Citation2014; Carson Citation2019a), investigative journalism is often also described as “quality journalism”. This implies that its subjects and methods are the same as in journalism in general; and that its specificity resides in the extraordinarily high quality of work and “in the manner in which [the reporter] conceptualizes a reporting project” (Aucoin Citation2005, 85). Some professionals are unwilling to define too precisely what they consider to be a tautology or the very essence of journalism (Charon Citation2003, 160; Aucoin Citation2005). This view considers investigative work as a fundamental component of journalistic identity.

Investigative journalism goes beyond description and attributed opinion to uncover information, typically about powerful individuals or organizations. Many investigative skills will be used by “ordinary” journalists every day. […] The concept remains a vital part of the self-identity even for journalists who themselves rarely conduct in-depth investigations. (Harcup Citation2015, 108)

Contrary to what some professionals like to say, investigative journalism is not just good, old-fashioned journalism that is well done. […] Investigative journalism involves exposing to the public matters that are concealed—either deliberately by someone in a position of power, or accidentally, behind a chaotic mass of facts and circumstances that obscure understanding. It requires using both secret and open sources and documents. (Hunter Citation2011, 8)

Despite these contrasting points of view, both conceptions share the idea that investigative journalism consists of independently exposing wrongdoing based on collecting information of public interest that was in some way concealed. Implicitly and often explicitly, this requires an unusual amount of effort, resources (time, money), methods and tools. However, such views do not specify how much of any of the above is required for a journalistic endeavor to qualify as investigative.

Based on the fundamentals of journalism, one could say that investigative journalism “pushes these standards to the limit” (Lemieux Citation2001, 56). At a symbolic level, it encompasses “the core informational role of journalism” (McQuail Citation2013, 89). In this way investigative journalism may share a set of techniques with conventional journalism, but it pushes them to a higher level of complexity, requiring more skills and time to master its “craft” (Kaplan Citation2013, 10).

In this perspective, any definition of investigative journalism refers to a journalistic ideal. At a symbolic level, it entails a legitimizing function (Marchetti Citation2002) that plays a key role for the field of journalism insofar as it also has external uses, allowing journalists to reaffirm their professionalism. This is even more true since the boundaries of journalism have been increasingly challenged and, with them, the legitimacy and unique competence of those who practice it (Neveu Citation2013). Following Neveu, the symbolic challenge is now to defend oneself against threats to the exercise of the profession or the expansion of journalistic and peri-journalistic practices, perceived as abuses: the rise of communicators, blogs, fake news, “connivance journalism”, editorialists, etc. In the same time, this journalistic ideal carries the risk of excluding other forms of legitimate journalistic practice from the scope of professionalism, while including others that may have little to do with methodologies specific to investigative reporting.

The continued use of reporting that appeared to rely on investigative techniques may be regarded as a way of legitimating a range of activities as journalism. Media organizations sought to mobilize investigative journalism to meet their own demands for marketable, sensationalist and populist content. This was made more possible by journalism's own indeterminacy over defining what investigative journalism was, and its weak sense of professionalism. (Bromley Citation2005, 321)

Investigative Journalism as a Shared Set of Values and Practices

Our theoretical standpoint is based on the discursive conceptions of journalism (Brin, Charron, and De Bonville Citation2004; Deuze Citation2004, Citation2005; Hanitzsch Citation2006, Citation2007; Hanitzsch and Vos Citation2017). In this perspective, journalism is understood as “a particular set of ideas and practices by which journalists, consciously and unconsciously, legitimate their role in society and render their work meaningful for themselves and others” (Hanitzsch Citation2007, 369; see also Ruellan Citation2007, 88). We consider that investigative journalism can be studied in the same vein: as a shared set of values and practices by a given group of practitioners in a given context, which extends beyond a genre or a conception limited to journalistic fundamentals: an “occupational ideology” following Hanitzsch.

This approach allows us to apprehend a set of practices and representations shared by a group of actors with unclear professional boundaries (Ruellan Citation2007; Descamps Citation2017). It emphasizes professional discourses and their legitimization function in parallel with the practices.

In this way, we can draw from subjective discourses a shared, intersubjective truth (that of the actors) and begin to identify the reasons for the gap between discourses and practices, between journalistic roles and their concrete realization; objects that remain under-studied in the literature (Raemy, Beck, and Hellmueller Citation2018).

Methodology

Observing the making of investigative journalism is challenging for several reasons. In practice as in theory, the line between “regular” journalism and investigative journalism remains blurry: when do we move from one to the other? In addition, the sensitivity of some stories keeps investigative processes behind closed doors, making the work near impossible to observe. Narratives and the question of the definition are thus the first key elements of our study.

With this in mind, we opted for semi-directive interviews with a narrative focus inspired by the life story interviews defended by Bertaux (Citation2016) and Kaufmann's methodology (Citation2011). Narrative interviews are of particular interest “to address issues related to the meaning that actors attribute to events or their actions; to events themselves; to representations; to values or (in a more descriptive perspective) to practices” (Derèze Citation2009, 107, our translation). We combined this with an exploratory observational fieldwork in three different investigative units.

The predominant challenge for the selection of respondents was that investigative journalists do not form a proper distinctive group in Switzerland. While few news outlets have dedicated investigative teams and there is a national organization aiming to unite professionals interested in investigative reporting, our exploratory research showed that the journalists producing investigative work are to be found in various places and situations. Also, far from all eligible journalists participate in this national network which hasn't yet successfully developed its’ community. This is also a “symptom” of the vagueness already mentioned above that surrounds the definition of investigative journalism … and investigative journalists. As De Burgh puts it:

An investigative journalist is a man or woman whose profession is to discover the truth and to identify lapses from it in whatever media may be available. The act of doing this generally is called investigative journalism and is distinct from apparently similar work done by police, lawyers, auditors and regulatory bodies in that it is not limited as to target, not legally founded and usually earns money for media publishers. (De Burgh Citation2008, 22)

We used a combination of selection methods. We selected our respondents trough key informants (experts of the field), our own professional network and preliminary knowledge of the sector, “self-proclaimed” investigative journalists (i.e., presenting themselves as such on their personal webpage or social media, for example) and “snowball” sampling. To ensure the largest possible diversity of profiles in the corpus, we included borderline cases (1 journalist ostensibly not practicing in-depth reporting, 2 foreign journalists, 1 former journalist working for a NGO, 1 culture journalist, 1 very local journalist). The targeted population is in fact constituted by very diverse journalistic profiles, including managers.

Our final corpus consists of in-depth interviews (between 60 and 120 minutes each and conducted between October 2017 and June 2019) with 23 journalists (11 female), whose anonymity was preserved. Twenty of them worked in the Swiss French-speaking media field at the time we collected the data and one journalist worked for a German-speaking media. Two were senior French journalists. Out of the 23 journalists interviewed, 17 worked for the written press, and 14 were considered “confirmed” investigators in the sense that they conduct in-depth investigation on a regular basis and are known for it by their peers, most of them having won one or more awards. Given the market concentration in the Swiss press, several of these journalists worked for the same publishers (Tamedia and SSR, among others), but in different publications. In the following, we choose to refer to them with pseudonyms.

Interviews were divided into four parts: (1) a description of the interviewees’ professional activities and the organization of work in their media outlet, (2) narratives about in-depth investigations conducted by the respondents, (3) their perceptions and understandings regarding investigative journalism in general (definitions) and (4) professional and educational paths which lead them to the current position. With an open-ended approach, we decided not to confront the journalists to any available definition of investigative journalism, and instead to let them describe their own conceptions, sometimes outlining an explicit definition and sometimes implicitly suggesting one through their narrated practices.

Regarding coding and analysis, we conducted a thematic content analysis of all interview transcriptions, by applying codes to text segments with the help of qualitative analysis software (Atlas-ti). The list of codes was created semi-inductively, starting with a set of predefined themes based on the interview guide. Since the definition of investigative journalism came out as a major theme in our transcripts, we focused our coding on how the journalists’ expressed their views thereof. These expressed views were sometimes in strong contradiction with the narrated practices of the actual investigative work experiences, and we decided to code for explicit as well as implicit criteria. Following a basic content analysis procedure, these codes were assembled into categories, and the categories were adapted and expanded as the coding progressed.

Results and Discussion

Despite a variety of profiles in our sample, our first analyses of the implicit and explicit definitions of investigative journalism reveal a strong homogeneity on three aspects. This section describes these three similarities found in our respondents’ narratives. We then identify observed variations and suggest several interpretations.

First, all journalists referred to investigative journalism as a higher form of journalism—more “successful”, “noble”, “demanding” or “complex” in the words of our interviewees. This was an expected result, as the literature review suggests. Second, our interviewees presented difficulties and reluctance when it came to defining investigative journalism, which we relate to their explicit and implicit definitions. And third, the interviewees nuanced and adjusted their definition of investigative journalism depending on what they were talking about. We argue that this allows them to develop a flexible viewpoint to assess their own journalistic work and engagement, while maintaining an ideal conception of investigative reporting.

Idealistic Conception and Definitional Challenges

Although it might seem that defining what constitutes investigative journalism is a basic question, all of our interviewees either showed reluctance or encountered some difficulty in formulating what precisely it meant to them. Few respondents were comfortable with articulating a definition and many showed some sign of embarrassment or reluctance: “I’ve always had a lot of trouble with this term, it makes me uncomfortable because we all do the same job, more or less”, commented Peter for instance, an experienced investigator working for a country-wide publisher.

It proved easier for them to say what investigative journalism is not, which is congruent with previous research (Lacan et al. Citation1994, quoted in Descamps Citation2017, 296). We then started questioning the interviewees on this fact, and the obstacles to defining investigative journalism became a topic of discussion in itself. A first explanation that emerged was that to many of our interviewees, investigating was in fact what journalism in general is all about, as Patricia, a senior journalist in a regional daily newspaper, put it:

The word investigation, in a sense, doesn't mean much because when you’re doing your job, you’re always investigating a little.

I consider it to be the most essential part of the practice of journalism; it is the closest thing to the definition of journalism. To me, it's normal journalism.

In addition, by stating a clear definition, one would at the same time specify the standards by which to measure the degree to which their own work is truly journalistic. Living up to the ideals of investigative work can be quite difficult when juggling with day-to-day news routines (Labarthe Citation2019b). Especially so for journalists working in local newsrooms or small teams, with no explicit investigative prerogative at all.

Michel, a specialist investigator working for a non-profit structure, underlined that there is something at stakes relating to the unity of the field:

Well, I don't really like the idea of making a distinction between journalism and investigative journalism (…) it actually suggests a two-step journalism, two categories of journalists: those who do what is the most noble art of journalism and then the others. And that's fundamentally wrong. Especially since this distinction is precisely the whole problem of the definition. It is finally quite a challenge. […] Is an investigation about asking yourself a question in the morning and then answering it in three phone calls or is it about spending months and producing a book at the end? I don't know really … You tell me, and then I can tell you if I have already done any in my life or not (laughs).

The job, it remains the same. It's the time we put in, the involvement we put in, uh … the tenacity we can put in that will make the difference. (Peter, specialist senior journalist for a large media group)

Investigative reporter Jonathon Calvert described the time commitment this way: “some stories you make five calls on, some twenty. When you are making a hundred, that's investigative journalism”. (De Burgh Citation2008, 7)

We found further insights with the narrative-oriented questions in our interviews, where the journalists were asked to recount how they worked on one or several investigative pieces. In these segments, we identified that when talking about—and simultaneously assessing—their own work, our respondents systematically relied on a distinction between process (investigative work) and product (investigative publications). When assessing their own work (answering our question: “what makes this piece investigative?”), they would refer to the process involved. They would say: It was an in-depth investigation, because I did this and that … . This was a good piece, because I did this in that way … This way, the ideal conception of investigative journalism is made compatible with each respondent's experience.

Ultimately then, professionals show a more flexible understanding of investigative journalism than idealized discourses suggest. We further describe this flexibility by looking at how journalists rely on a gradual and multilevel conception of investigative work, which makes it possible to be in agreement with both a purist understanding of what journalism is and should be all about, and with the diversity of actual journalistic practices.

A Gradual and Multi-Level Investigative Commitment

To further understand how journalists deal with the difficulties of defining investigative journalism as “just regular journalism”, we had to abandon a dichotomous categorization: analyzing their narratives suggests that the definition unfolds on a continuum stretching from basic reporting all the way to full-fledged investigative endeavor. The interviewees used words like “levels”, “degrees”, “gradation” to talk about what counts as investigative reporting. They also mentioned various investigative pieces as “models” or “best examples”, some of which were “little stories” and others “big ones”.

Some respondents explicitly conceptualized this. For instance Sally, who was running a small investigative unit in a local daily, said: “There are different degrees of investigations … investigations at various levels”, and Fabrice, a journalist for the public broadcast told us: “I don't know if there are diverse forms of investigative work but maybe a gradation”. When they were not explicit, interviewees’ explanations still referred to a gradual framework in more implicit ways. For instance Richard, a senior local journalist, said:

When you’re the one who got the information, and you have to go check things out and everything, you’re already de facto in the investigation mode, to a certain extent. But then, when the stakes aren't incredible, when there's no anonymous stuff, then it's just a little investigation, I’d say. (our italics)

We gathered the criteria into three a-posteriori categories: motive, extent of efforts and technique, each providing answers to one of three related questions: (1) what drives journalistic activity?, (2) what amount of work was provided?, and (3) what particular means or techniques were deployed? They are all complementary indicators of what counts as an “investigative commitment” of various degrees.

A first basic observation provided by this categorization is that the main defining aspects of investigative journalism focus on civic engagement, rigor, method and depth; which fits well with contemporary conceptions of investigative reporting mentioned above.

Motive and Extent of Efforts as Key Criteria

Expectedly, we found criteria that match those provided by the professional and academic literature. A very common aspect was for instance the importance of Expose wrongdoing and Reveal secrets:

[Investigative journalism] is about uncovering facts that some people often wish they didn't want to see in writing, showing what one doesn't really want to see. (Carole, investigative journalist for the Sunday press)

When I was in New York, American journalists were saying ‘Yes, the French talk about investigations, but all they know how to do is scare things away and their investigations are unilateral; they rely on a good leak and that's enough to say it's an in-depth investigation. We go deeper, we do a pre-investigation, we don't rely only on a leak, but we start from that leak to build something, to look further’.

There must be a whole job behind an investigative piece that highlights a machinery, a dysfunction. Just because you a get a confidential record does not mean […] You just pass on a document; you’re just an intermediary.

All the data were public. But you have to go get them, and then you have to report them. No one else was going to look for them, no one had thought that [it could be interesting]. To me, that is still in-depth investigation.

Although the criteria of the group “Motives” (Expose wrongdoing, Reveal secrets, Novelty, etc.) are usually those invoked in explicit discourses, journalists’ narratives often resort to the extent of efforts (for instance Initiative, but also other criteria such as Time and money, Quantity of sources, …) to claim legitimacy as “investigative”. In other words, the amount of work is just as important as the underlying motive.

In addition, elements regarding the techniques and methods process were mentioned. Certain type of tools and methods (datajournalism, “shoeleather” fieldwork) and sources (confidential, high-level) are seen as more investigative than others, which confirms the trend noted above. The ways stories are told (Storytelling) was also mentioned as an indicator: a compelling demonstration, a step-by-step narrative, etc. But overall our respondents regarded these elements as secondary when evaluating an investigative story. Which is why they will not be detailed here.

Arguably, the continuum we presented above allows practitioners to make sense of their work while staying in agreement with an ideal gold standard. The model suggests the standards a perfect in-depth story would have to comply with: meeting and maximize all the criteria identified in . However, in order to qualify as investigative, a story requires only a combination of these criteria, those regarding “Motives” and “Extent of efforts” being central.

Conclusion

Our interview data shows that there is a shared sense of the importance of investigative journalism, which sets the standards of good if not the best journalism. This entails a strong normative implication which is at odds with actual practice however, since these standards aren't always met. It is consistent with a conception of investigative journalism as an occupational ideology (Hanitzsch Citation2007). The disconnection between ideal and practice is nothing new to journalism studies, but our research takes a closer look at how it is built into professionals’ conceptions of investigative journalism.

The analysis of the explicit and implicit definitions of our respondents shows that they endorse far more nuanced conceptions of investigative journalism than one might expect. Interviewees’ narratives built on a mix of various elements used to specify what constitutes investigative journalism. We distinguished three types of defining criteria: motive, extent of efforts and technique involved. These criteria hardly materialize simultaneously in practice and they are permutable: they can be used to fill in for and counterbalance each other. Professionals rely on a gradual and multilevel definition. We showed how, to them, investigative journalism exists on a continuum between a full-fledged investigative endeavor and the most basic reporting.

The empirical scope of our research was restricted to a reduced linguistic area, in a single small country, but whose situation is comparable to other (European) countries on these points (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004; Bonfadelli et al. Citation2011; Bonin et al. Citation2017). Given these similarities we described earlier, we believe that the idea of a continuum which allows for intermediary forms of investigative work can help understand journalistic realities beyond geographical boundaries. This speaks in favor of taking into account the multiple aspects of investigative journalism rather than a single elitist definition, which would exclude various forms of in-depth journalistic work. And it has significant implications for instance when thinking about investigative journalism in a newsroom; by separating journalists entitled to investigate from the others, the latter are disqualified even though they share the same occupational ideology.

Our results also suggest that professionals engage with investigative journalism in a perspective of personal commitment. Interviewees tend to value the extent of efforts that were deployed for a given story, and not just traditional constitutive elements such as exposing wrongdoing and revealing news of public interest. We can hypothesize that this dimension of personal commitment is key to the experience of journalists engaging in investigating a story. This centrality of personal commitment in journalists’ representations is also noteworthy given the collective effort often required by investigative work, especially in large-scale consortiums or networks. This and the results presented above raise three further questions which fit into our wider research program.

First, the question of how the criteria journalists use relate to the individuals’ status and their organizations’ specificities. For instance, the interviewees’ narratives seem to vary based on their professional status. The width of the continuum of possible investigative commitment seems to be inversely proportional to the status of investigator: the less “legitimate” the journalist, the blurrier the line between conventional reporting and investigation. An “illegitimate” journalist would be one who does not enjoy a formal recognition—job title, awards won, official member of a dedicated unit—from their peers, even if they may conduct in-depth investigations.

Second, these insights about definitional stances of professional journalists can provide a basis to applied studies in the management of investigative journalism. Combined with other data and methods, such as observational newsroom fieldwork, the analysis of investigative criteria might help shed light on the conditions and managerial strategies to help more journalists in the newsroom to engage in investigative work.

Third, this analytical perspective should be applied to cases in other linguistic and cultural contexts. In French, the term “investigative journalism” translates quite easily with “journalisme d’investigation” or “journalisme d’enquête” but depending on the journalistic vocabulary in use in a given language, the scope of relevant criteria may vary. Extending the research to other local cultures of journalism and structural (legal, political, economic) contexts will also provide interesting results to compare to.

These avenues of research are increasingly important given that the field of journalism is searching to consolidate or re-establish its democratic function and that investigative journalism is often considered crucial in this regard. How to enhance the role and the image of journalism are key issues, and the positive aura of investigative journalism can imbue journalists, perhaps encouraging them to push their investigative commitment further up the continuum to perfect their motives, efforts and technique. Celebrating investigative journalism uncritically may on the contrary produce the undesired effect of embroiling journalists in a mythical, self-justifying conception, which would be sterile in terms of renewal of the field.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. 2016. The Crisis of Journalism Reconsidered: Democratic Culture, Professional Codes, Digital Future. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Aucoin, James. 2005. The Evolution of American Investigative Journalism. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

- Baggi, Guia Regina. 2011. “Nonprofit Investigative Journalism in Europe: Motives, Organizations, and Practices.” University of Hamburg.

- Bertaux, Daniel. 2016. Le récit de vie. 4th ed. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Bonfadelli, Heinz, Guido Keel, Mirko Marr, and Vinzenz Wyss. 2011. “Journalists in Switzerland: Structures and Attitudes.” Studies in Communication Sciences 11 (2): 7–26.

- Bonin, Geneviève, Filip Dingerkus, Annik Dubied, Stefan Mertens, Heather Rollwagen, Vittoria Sacco, Ivor Shapiro, Olivier Standaert, and Vinzenz Wyss. 2017. “Quelle Différence? Language, Culture and Nationality as Influences on Francophone Journalists’ Identity.” Journalism Studies 18 (5): 536–554.

- Brin, Colette, Jean Charron, and Jean De Bonville. 2004. Nature et transformation du journalisme: théorie et recherches empiriques. Québec: Presses Université Laval.

- Bromley, M. 2005. “Subterfuge as Public Service: Investigative Journalism as Idealised Journalism.” In Journalism: Critical Issues, edited by Stuart Allan, 313–327. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Carson, Andrea. 2019a. Investigative Journalism, Democracy and the Digital Age. New York: Routledge.

- Carson, Andrea. 2019b. “Why Investigative Reporting in the Digital Age Is Waving, Not Drowning.” The Conversation. 4 août 2019.

- Charon, Jean-Marie. 2003. “Le journalisme d’investigation et la recherche d’une nouvelle légitimité.” Hermès, nᵒ 35: 137.

- De Burgh, Hugo. 2008. Investigative Journalism. New York: Routledge.

- Derèze, Gérard. 2009. Méthodes empiriques de recherche en communication. Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur.

- Descamps, Camille. 2017. “Analyse compréhensive d’un sous-groupe professionnel : le cas des journalistes belges francophones : une identité négociée entre distanciation et engagement.” UCL – Université Catholique de Louvain.

- Deuze, Mark. 2004. “Journalism Studies beyond Media: On Ideology and Identity.” Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies 25 (2): 275–293.

- Deuze, Mark. 2005. “What Is Journalism? Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered.” Journalism 6 (4): 442–464.

- Dingerkus, Filip, Annik Dubied, Guido Keel, Vittoria Sacco, and Vinzenz Wyss. 2018. “Journalists in Switzerland: Structures and Attitudes Revisited.” Studies in Communication Sciences, nᵒ 1 (november).

- Donsbach, Wolfgang. 2009. “Journalists and their Professional Identities.” In The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism, edited by Stuart Allan, 82–92. New York: Routledge.

- Ettema, James S., and Theodore L. Glasser. 1998. Custodians of Conscience: Investigative Journalism and Public Virtue. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ettema, James S., and Theodore L. Glasser. 2006. “On the Epistemology of Investigative Journalism.” In Journalism: The Democratic Craft, edited by G. Stuart Adam and Roy Peter Clark, 126–140. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Communication, Society, and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas. 2006. “Mapping Journalism Culture: A Theoretical Taxonomy and Case Studies from Indonesia.” Asian Journal of Communication 16 (2): 169–186.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas. 2007. “Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Toward a Universal Theory.” Communication Theory 17 (4): 367–385.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, Folker Hanusch, Claudia Mellado, Maria Anikina, Rosa Berganza, Incilay Cangoz, Mihai Coman, et al. 2011. “Mapping Journalism Cultures across Nations: A Comparative Study of 18 Countries.” Journalism Studies 12 (3): 273–293.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, and Tim P. Vos. 2017. “Journalistic Roles and the Struggle Over Institutional Identity: The Discursive Constitution of Journalism.” Communication Theory 27 (2): 115–135.

- Harcup, Tony. 2015. Journalism: Principles and Practice. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Hunter, Mark Lee. 1997. Le journalisme d’investigation aux États-Unis et en France. Vol. 3239. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France-PUF.

- Hunter, Mark Lee. 2011. Story-Based Inquiry: A Manual for Investigative Journalists. Paris: UNESCO.

- Lacan, Jean-François, Michel Palmer, and Denis Ruellan. 1994. Les journalistes: stars, scribes et scribouillards. Paris: Syros.

- Kaplan, Andrew D. 2008. “Investigating the Investigators: Examining the Attitudes, Perceptions, and Experiences, of Investigative Journalism in the Internet Age.” University of Maryland.

- Kaplan, David E. 2013. “Global Investigative Journalism: Strategies for Support. A Report to the Center for International Media Assistance 2nd Edition.” Center for International Media Assistance.

- Kaufmann, Jean-Claude. 2011. L’entretien compréhensif – L’enquête et ses méthodes. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Labarthe, Gilles. 2018. “Des journalistes d’investigation face au ‘5e pouvoir’. Collaboration, négociation et conflit avec des sources officielles en Suisse romande.” Sur le journalisme, About journalism, Sobre jornalismo 7 (2): 108–125.

- Labarthe, Gilles. 2019a. “Mener l’enquête: arts de faire : une approche socio-ethnographique des récits de légitimation et des pratiques d’investigation de journalistes en Suisse romande.” Université de Neuchâtel.

- Labarthe, Gilles. 2019b. “Journalistes en Suisse romande. Étude de quelques mobilisations stratégiques et tactiques des « fondamentaux » du métier, et de l’investigation en particulier, face aux risques liés à l’uniformisation dans la presse.” Communication. Information médias théories pratiques, vol. 36/1 (april).

- Lemieux, Cyril. 2001. “Les formats de l’égalitarisme : transformations et limites de la figure du journalisme-justicier dans la France contemporaine.” Quaderni 45 (1): 53–68.

- Marchetti, Dominique. 2000. “Les révélations du ‘journalisme d’investigation’.” Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 131 (1): 30–40.

- Marchetti, Dominique. 2002. “Le ‘journalisme d’investigation’ : Genèse et consécration d’une spécialité journalistique.” In Juger la politique : Entreprises et entrepreneurs critiques de la politique, edited by Jean-Louis Briquet, and Philippe Garraud, 167–191. Res publica: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Matheson, Donald. 2009. “The Watchdog’s New Bark: The Changing Roles of Investigative Reporting.” In The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism,edited by Stuart Allan, 82–92. New York: Routledge.

- McQuail, Denis. 2013. Journalism and Society. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Neveu, Erik. 2013. Sociologie du journalisme. Paris: La Découverte.

- Plenel, Edwy. 2014. Le droit de savoir. Paris: Points.

- Protess, David. 1991. The Journalism of Outrage: Investigative Reporting and Agenda Building in America. New York: Guilford Press.

- Raemy, Patric, Daniel Beck, and Lea Hellmueller. 2018. “Swiss Journalists’ Role Performance: The Relationship between Conceptualized, Narrated, and Practiced Roles.” Journalism Studies, janvier, 1–18.

- Ruellan, Denis. 2007. Le Journalisme ou le professionnalisme du flou. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble.

- van Eijk, Dick. 2005. Investigative Journalism in Europe. Amsterdam: Vereniging van Onderzoeksjournalisten.