ABSTRACT

People with high dark triad levels, consisting of subclinical narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, can have a destructive impact on their team members, subordinates, and the organisation. Recent research has even found that the higher the leadership position, the more dark triad traits were displayed. As coaching is often for people in (higher) leadership positions, the following study with 64 coaches investigated the dark triad traits among their clients and how this affected the coach as well as the coaching. The results show that the higher the client’s leadership level was, the higher their dark triad level was perceived and, thus, the more anxious and distressed the coaches were regarding the client, leading to less coaching success. Although the coaches did not name a definite strategy for dealing with such a client, the results showed that the higher their approach motivation was, the more successful the coaches was. The results depict the danger of high dark triad levels amongst coaching clients and its influences on the business coaching, implying theoretical and practical considerations.

KEYWORDS:

Practice Points

Field of practice area(s) in coaching: Our research is relevant for executive and business coaches – mostly with clients in leadership positions

The primary contribution to coaching practice: Raising awareness for dark triad clients, their effect on both the coach and the coaching, and the difficulty in dealing with them

Tangible implications for practitioners:

o The chances of seeing dark triad clients in coaching

o Their negative effect on the coach in terms of anxius inhibition and distress

o The importance of staying approach-motivated to have a successful coaching

o The benefits of mindfulness and supervision as implications that could help

Introduction

Imagine you coach a client who you would describe as narcissistic, highly power-motivated, and cold-hearted. Such people with high dark triad levels, i.e. high levels of subclinical narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy can have destructive effects on their workplace environment (O’Boyle et al., Citation2012; Spain et al., Citation2013). However, difficulties in coaching have not been well-researched so far (Graßmann & Schermuly, Citation2017; Oellerich, Citation2016). Thus, ‘the dark side of personality has yet to be explored as a moderator of coaching effectiveness even though initial work has examined the bright side of personality’ (Grover & Furnham, Citation2016, p. 35). The following research therefore investigates how clients with high dark triad levels, i.e. high levels of subclinical narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy (Paulhus & Williams, Citation2002), affect the coach and, thus, the coaching.

The dark triad and its negative outcomes

Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy are distinct constructs that overlap, as all of them can be considered ‘dark‘ because of their low value of empathy and ethics (Paulhus, Citation2014).Footnote1 More precisely, narcissists show high levels of arrogance, feelings of inferiority, an unstable need for recognition and superiority, hypersensitivity and anger, lack of empathy, amorality, irrationality and inflexibility and paranoia (Rosenthal & Pittinsky, Citation2006). Machiavellians are power-motivated, leading to ruthless, non-agreeable and egoistic behaviour (Paulhus & Williams, Citation2002). Psychopathy is related to a decreased level of empathy, affect, guilt, and conscience (Babiak & Hare, Citation2006; Paulhus & Jones, Citation2015) but high levels of impulsiveness, uncooperativeness, hostility, and aggressiveness (O’Meara et al., Citation2011). In sum, narcissism can be described as an extreme self-image, Machiavellianism as an extreme power motivation, and psychopathy as extreme impulsiveness and thrill-seeking in subclinical form.

High dark triad values can be found in the workplace, leading to counterproductive work behaviour and destructive consequences for the company (O’Boyle et al., Citation2012; Spain et al., Citation2013). For example, people with high dark triad levels use strategies such as manipulation and exploitation (Lee & Ashton, Citation2005). Such manipulation tactics range from complimenting to threatening the other person (Jonason et al., Citation2012). Due to their manipulative and exploiting behaviour, their subordinates are negatively affected with regard to emotional exhaustion, job tension, depressed mood, low task performance, and low citizenship behaviour (Ellen et al., Citation2019; Mathieu et al., Citation2014; Volmer et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, this behaviour can badly damage ethical standards of as well as can increase bullying, unfair supervision, and conflict in the entire organisation (e.g. Boddy et al., Citation2010). To sum up, people with high dark triad levels can negatively affect the organisation and the people working there. Thus, imagine coaching a client with high dark triad tendencies.

Dark triad coaching clients

Coaching is a human resource development approach that is found to have many positive performance-related and work-related effects: Particularly regarding leadership, coaching increased the clients’ leader efficacy and self-efficacy, rating, commitment, and job satisfaction, as well as their subordinates’ ratings, commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions (Grover & Furnham, Citation2016). However, coaching can also lead to negative effects, such as coaches’ feelings of disappointment, pressure, guilt, frustration, emotional exhaustion, or stress (Schermuly, Citation2014). One cause for negative coaching outcomes can be a difficult client personality (Graßmann & Schermuly, Citation2017). Although there is no estimation of how often dark triad tendencies occur within the population, as there is no cutoff-value, it is believed that this number is higher amongst leaders (Babiak & Hare, Citation2006; Boddy et al., Citation2010; Grijalva et al., Citation2014; Schuh et al., Citation2014; Schyns, Citation2014). In line with this assumption, Diller, Czibor, et al. (Citation2020) found that the higher the leadership level was, the higher the person’s dark triad level was. Moreover, dark triad leaders have been shown to cause problems in the workplace (Harms et al., Citation2011). As coaching is mostly offered to people in leadership positions or requested for employees that led to difficulties in their work environment (International Coach Federation, Citation2016a), there is a higher probability of dark triad clients.

The coaching client’s motivation is a first assumption of why dark triad coaching clients could be difficult to deal with. However, narcissists can be quite motivated to develop themselves, as they strive for goals that help them make a great impression (high impression motivation; Van Dijk & De Cremer, Citation2006; Wallace & Baumeister, Citation2002). Similarly, Machiavellians can be highly motivated to attain their goals, as they seek to gain more and more power (high power motivation; McClelland & Burnham, Citation1976; Paulhus, Citation2014). Also, psychopaths are impulsively motivated for the thrill (thrill-seeking; Paulhus, Citation2014) and show motivation for power, money, and development (Diller, Czibor, et al., Citation2020). To sum up, dark triad clients can be highly motivated to take part in a coaching.

However, an interaction with dark triad people can still be difficult due to their unethical strategies, such as manipulation or mobbing, and troublesome interpersonal aspects (Southard et al., Citation2015). These factors question the coachability of such a client, as the client may not be open to self-exploration and any kind of feedback, as well as may not show trust and respect towards the coach (Giacobbi et al., Citation2002; Murphy, Citation2006). For example, Cavanagh (Citation2005) states that narcissism can be found among executive clients and can be difficult, as ‘they are often dismissive of others, arrogant, even contemptuous. They excel at promoting themselves […] and seek to blame others or the environment for poor performance’ (p. 27). Kets de Vries and Rook (Citation2018) address the same challenges of a narcissistic executive in a case study. As there are no statements on coaching clients with psychopathic tendencies, psychotherapy research reveals some problems coaches might face: Challenges with regard to clinical psychopathy include a high chance of client recidivism (Olver & Wong, Citation2006), high client resistance to change (Ogloff et al., Citation1990), and a difficult working alliance due to their callous and unemotional features (DeSorcy et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, Schiemann and Jonas (Citation2020) discuss the difficulty in coaching dark triad clients by interviewing two coaches in this regard, showing that clients with high dark triad tendencies can be quite challenging or threatening for coaches.

The threatening effect of dark triad coaching clients on coaches

This kind of behaviour, such as relational devaluation (e.g. power games or displacement of guilt) or resistance to change, can be perceived as a threat for one’s basic needs, emotional well-being, and physical health (Gerber & Wheeler, Citation2009; Van Dellen et al., Citation2011). If there is not only a rewarding stimulus, such as the benefits of a coaching for the coach (e.g. helping client), but also a threatening stimulus, a person’s behavioural inhibition system (BIS) sets on: The person is anxiously inhibited due to the two conflicting stimuli (Corr, Citation2004; Lüders et al., Citation2016). Thus, a coach confronted with a dark triad client may activate feelings of anxious inhibition, being in conflict with how to react. Kilburg (Citation2002) reports the case of one client who was ‘a bright, energetic, aggressive, but somewhat abusive leader who struggled with her temper’ (p. 286), making him as a coach feel ‘anxious’ (p. 287).

In most situations, this BIS activation automatically decreases, as people show approach-oriented behaviour (behavioural approach system; BAS) in terms of a direct solution (e.g. dealing with the client via coaching strategies or terminating the coaching) or indirect solution (e.g. making oneself feel better or more protected) (Jonas et al., Citation2014; Lüders et al., Citation2016). However, if this BIS activation stays over a longer time, such as a permanent BIS-increase due to a coaching process over several weeks, it can lead to an experience of distress, i.e. long-term extreme helplessness and sorrow (Abdollahi et al., Citation2011; Routledge et al., Citation2010).

The present research

The present research investigates dark triad coaching clients and their effect on the coach and the coaching. As a higher dark triad level is linked to a higher leadership level (Diller, Czibor, et al., Citation2020), it was first hyothesized that the higher the client’s leadership level, the more dark triad the client is described by the coach (Hypothesis 1; H1). Based on the dark triad people’s maladaptive and, thus, threatening behaviour (Blair et al., Citation2008; Van Dellen et al., Citation2011), we further hypothesised that not only the higher the client’s leadership level, the more dark triad the client is described by the coach, but also that a higher coach-perceived dark triad level leads to more coach’s BIS activation and, thus, distress; however, we do not expect any direct or total effect of the client’s leadership level on the coach’s BIS activation or distress (Hypothesis 2; H2).

Subsequently, as the coach’s anxiety can impair the coaching success (De Haan, Citation2008; Schermuly & Bohnhardt, Citation2014), we hypothesised building upon H1 and H2 that the higher the client’s leadership level, the more dark triad the client is perceived, which leads to more coach’s BIS activation and, thus, less coaching success in terms of less coach-perceived client need fulfilment and, thus, less coaching satisfaction; again, we do not propose any direct or total effect of the client’s leadership level on the coach’s BIS and the coaching success (Hypothesis 3; H3). As BAS activation makes people remain able to act and to find direct and indirect solutions (Lüders et al., Citation2016), we expect that the coach’s BAS activation results in greater less coaching success in terms of greater coach-perceived client need fulfilment and, thus, more coaching satisfaction (Hypothesis 4; H4). Moreover, we we asked the coaches about successful and also unsuccessful strategies qualitatively and quantitatively.

Method

Sample

Coaches

External business coaches were recruited via a social network platform for coaches (XING Coaches + Trainer) due to self-reportedly having had an experience with a dark triad coaching client. As our hypotheses include the clients’ leadership and therefore work positions, we excluded nine of the 73 coaches who described a retired or job-seeking client.Footnote2 Our final sample therefore consists of 41 female and 23 male coaches (31–75 years; M = 51.86, SD = 10.11) with different educational and professional backgrounds (see Appendix A). Due to their varying backgrounds, coaches may have been differently trained and experienced in dealing with dark triad clients.Footnote3 All coaches took part in our online study voluntarily and without compensation.

Described clients

The coaches were asked to describe one specific dark triad client case. Out of the 64 clients (25 female, 39 male) described, 13 were employees, 7 were low-level leaders, 14 were high-level leaders, 16 were executives and 14 were entrepreneurs. These clients’ main reasons for having a coaching were having difficulties in dealing with others (44%), professional reorientation (42%), communication issues (31%), and leadership improvement (31%). The coaches were further asked whether yes or no this client can be seen as narcissistic, Machiavellian, and/or psychopathic had narcissistic, defining the three subclinical trait forms (Paulhus & Williams, Citation2002). The clients were mostly described as narcissistic (57%) compared to psychopathic (17%), and Machiavellian (10%) (17% mixed forms). In addition, an open field below every dark triad trait enabled the coaches to shortly describe why the client showed the respective dark triad trait. The narcissistic clients were mostly described as self-absorbed and easily offended; the descriptions of Machiavellian clients evolved around their high power motivation and their strategic behaviour; psychopathic clients were described as showing callousness and impulsiveness.

Design

Via XING Coaches + Trainer, a social network platform where clients can book coaches, we forwarded a survey on difficult coaching clients to their coaches. This study was granted by the Ethical Committee and the coaches agreed to an informed consent at the beginning of the study, including the acquisition of personal data and two questionnaires. The coaches first filled out a first questionnaire on their most challenging/difficult coaching client (Graßmann et al., Citation2020). After this questionnaire, the coaches were asked about whether they had a dark triad client and if so to please continue with the second questionnaire (start of this study’s questionnaire). As a thank you for filling out the first or both questionnaires, the coaches received an overview of the results of the first questionnaire.

In this study’s questionnaire, the coaches were asked about their clients’ dark triad traits qualitatively and quantitatively in terms of how the client was perceived by the coach. Subsequently, questionnaires on the dark triad traits, BIS, BAS, and distress followed. Then, the coaches were asked qualitatively and quantitatively about not helpful and helpful strategies concerning the dark triad client. In the end, the coaching success was measured by the client’s need fulfilment and coaching satisfaction. Based on findings on need fulfilment, need fulfilment is one key outcome as it can lead to several positive effects, such as positive affect, well-being, engagement, (job) satisfaction, commitment, and performance (Van den Broeck et al., Citation2016). To not only measure need fulfilment, we also included coaching satisfaction measures that were mostly used for measuring proximal coaching success, such as a satisfaction rating and a goal attainment rating (Grover & Furnham, Citation2016).

Measures

Client’s dark triad traits

To measure the perceived client’s dark triad traits more quantitatively, the ‘dirty dozen‘ questionnaire by Jonason and Webster (Citation2010) was used. This questionnaire consists of four items per dark triad trait, which were reformulated into a third-person perspective and which ranged on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (fully): Narcissism (e.g. ‘During the coaching, my client wanted to be admired by me‘ [original: ‘I tend to want others to admire me‘]), Machiavellianism (e.g. ‘During the coaching, my client tended to manipulate me to get his/her way‘ [original: ‘I tend to manipulate others to get my way‘]), and psychopathy (e.g. ‘During the coaching, my client tended to be callous or insensitive‘ [original: ‘I tend to be callous or insensitive‘]). As all three dark triad traits significantly correlate with each other (r = .62–.74, p< .001), the three traits are perceived as one scale (α = .90).

BIS and BAS activation

BIS and BAS activation were measured by a BISBAS scale Agroskin et al. (Citation2016). BIS consists of four items (α = .72; e.g. ‘anxious‘) and BAS of seven items (α = .87; e.g. ‘energetic‘), both ranging on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (fully).

Distress

Distress was measured with the K6 Psychological Distress Scale by Kessler et al. (Citation2002) ranging on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (fully) (α = .82, 6 items; e.g. ‘Because of the Coaching with the client I often felt hopeless‘).

Strategies in dealing with clients of the dark triad

Unsuccessful and successful strategies in dealing with clients of the dark triad were assessed qualitatively and quantitatively. After the open question, a list of 21 coaching strategies was provided to choose from (multiple answers possible), which was derived from coaching literature and interviews with experienced coaches. For exploratory purposes, we further assessed empathy with 14 self-developed items (α = .87; e.g. ‘As a coach I tried to understand the situation of my client‘), which were not used for computation.

Perceived coaching success: the perceived client’s need fulfilment and coaching satisfaction.

The client´s need fulfilment was measured with the Basic Need Satisfaction at Work Scale used by Deci et al. (Citation2001), asking in the third-person perspective ‘To what extent was coaching helpful for the client to … ‘, (17 items; e.g. ‘ … to be him/herself‘; α = .89), ranging on a Likert Scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (fully). Coaching satisfaction was measured by the coaching scale by Greif (Citation2017) with five items such as ‘To what extent was/were the coaching goal/s achieved in your estimation? ‘ and ‘How satisfied are you overall with the coaching? ‘ (α = .90; 5 items).

Analysis

The quantitative analysis was done via SPSS 24.0, using regression analyses and Process by Hayes for mediation modelling. The qualitative analyses for exploring successful and unsuccessful strategies in dealing with dark triad clients were done via the online evaluation programme QCA-MAP. The eight steps of the inductive category development according to Mayring (Citation2014, p. 80) were used: (1) Three inter-coders were introduced to our research question and the theoretical background; (2) the selection criteria, the category definition, and the level of abstraction (low) were explained; (3) the text material (the statements of the coaches) was worked through and categories were extracted from it; (4) a revision was made after 10% of the text; (5) the text material was then completely worked through; (6) no main categories were built; (7) the results of the inter-coders were then compared and adjusted (agreement check); (8) lastly, the final results were viewed, the frequencies of the extracted categories were calculated, and the data was interpreted.

Results

H1: clients’ leadership level influence on their dark triad level

To test the influence of the client’s leadership level on the perceived dark triad level, a regression was computed. In line with H1, clients with higher leadership levels were also perceived as having higher dark triad values with regard to the dirty dozen scale, R2 = .10, F(1, 62) = 6.85, p = .011.

H2: perceived client’s dark triad level influence on the coach’s anxiety and, thus, distress

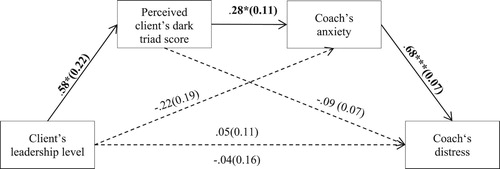

In line with H2, a further mediation analysis showed that there is no total or direct but indirect effect of the client’s leadership level on the coach’s distress but that this is fully mediated by the perceived client’s dark triad level and, thus, the coach’s anxiety: .11, CI[0.01;0.27] (see ). As expected, clients with a higher leadership level did not automatically predict higher coach anxiety or distress (total and direct effect). Only a perceived higher client’s dark triad score positively influenced the coach’s anxiety level, t(63) = 2.59, p = .012. This anxiety can over time lead to more distress so that a coach’s anxiety level positively predicted the coach’s distress, t(63) = 9.04, p < .001.

Figure 1. Process mediation analysis: How dark triad leaders influence the coach and coaching.

Note. Standard regression coefficients with the standard errors in the brackets are depicted with significant pathways being highlighted by thick arrow lines and the significance level (***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05). Non-significant pathways and independent variables are shown with dotted (arrow) lines. Direct effect: t(63) = 0.47, p = .642; total effect: t(63) = −0.24, p = .808; effect of leadership level on the perceived client’s dark triad score: t(63) = 2.62, p = .011.

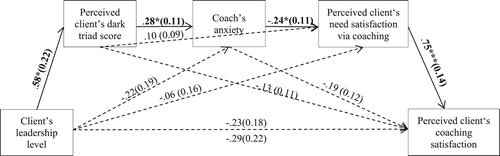

H3: dark triad level influence on anxiety and, thus, distress

Supporting H3, a mediation analysis shows no total or direct but indirect effect of the client’s leadership level on the coaching success but that this is fully mediated by the perceived client’s dark triad level and, thus, the coach’s anxiety: −.03, CI[−0.08;−0.00] (see ). As expected, clients with a higher leadership level did not automatically predict a lower coaching success in terms of need satisfaction and goal attainment (total and direct effect). Only a perceived higher client’s dark triad score positively influenced the coach’s anxiety level, t(63) = 2.59, p = .012. This anxiety make it difficult for the coach to fulfil the client’s needs in coaching, t(63) = 9.04, p < .001, which can lead to less coaching goal attainment, t(63) = 5.16, p < .001.

Figure 2. Process mediation analysis: How dark triad leaders influence the coach and coaching.

Note. Standard regression coefficients with the standard errors in the brackets are depicted with significant pathways being highlighted by thick arrow lines and the significance level (***p < .001; ** p < .01; *p < .05). Non-significant pathways and independent variables are shown with dotted (arrow) lines. Direct effect: t(63) = −1.23, p = .206; total effect: t(63) = −1.33, p = .187; effect of leadership level on the perceived client’s dark triad score: t(63) = 2.62, p = .011.

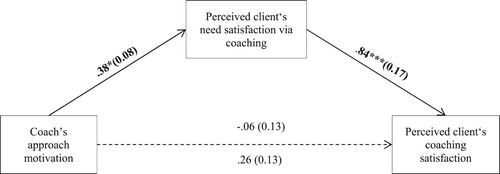

H4: the importance of the coach’s approach motivation

In line with H4, mediation analysis showed that there is an indirect effect of the coach’s approach motivation on the perceived client’s goal attainment, fully mediated by the perceived client’s need fulfilment in coaching: .32, CI[0.16;0.50] (see ). A higher approach motivation positively influenced the perceived client’s need satisfaction in coaching, t(63) = 4.50, p < .001. This perceived need satisfaction then positively predicted the client’s goal attainment, t(63) = 4.95, p < .001.

Figure 3. Process mediation analysis: How the coach’s approach motivation influences coaching.

Note. Standard regression coefficients with the standard errors in the brackets are depicted with significant pathways being highlighted by thick arrow lines and the significance level (***p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05). Non-significant pathways and independent variables are shown with dotted (arrow) lines. Direct effect: t(63) = −1.23, p = .206; total effect: t(63) = 1.96, p = .054.

Unsuccessful and successful strategies to deal with dark triad clients

Regarding the quantitative data, the three most named successful strategies for narcissism were showing appreciation (n = 34), building up trust (n = 31), and mirroring the client’s behaviour (n = 27); the three most named successful strategies for Machiavellianism were confronting the client (n = 11), giving the client feedback (n = 9), and letting the client self-reflect (n = 9); and the three most named successful strategies for psychopathy were showing empathy towards the client (n = 9), letting the client self-reflect (n = 8), and mirroring the client’s behaviour (n = 6). We further qualitatively asked the coaches about unsuccessful and successful strategies in dealing with the described client before providing the quantitative options. The answers were inductively qualitatively analyzed by two raters and only listed when both raters rated something as a strategy. The inductive qualitative analysis revealed that there are several approaches to deal with dark triad clients, particularly when it comes to narcissism: Overall, 106 strategies were named for narcissistic clients, 21 strategies were named for Machiavellian clients, and 20 strategies were named for psychopathic clients. However, most of these strategies were only named once (only 24 of the 147 strategies were named more than once) and most of these strategies were also found amongst the unsuccessful strategies named (12 of the 24 strategies were also named as unsuccessful). For example, to mirror the client’s behaviour, to confront the client, to show empathy, to give feedback, or to be clear and transparent were mentioned among successful and unsuccessful strategies (see Appendix B for all unsuccessful strategies named). This leaves 12 potential strategies in dealing with dark triad clients (see ). Among these strategies, practicing mindfulness was the most named strategy.

Table 1. Qualitative data for successful strategies that were named more than once and were not named among the unsuccessful strategies, ordered by dark triad tendency.

Discussion

The present research investigated the relationship amongst leadership levels and the dark triad traits and how clients with high dark triad values affect the coach and the coaching. The results first depict there is a positive relationship between the dark triad traits and the leadership level. This influence of the leadership level on the dark triad level replicates findings from leadership self- and other-assessments (Diller, Czibor, et al., Citation2020). As people with high dark triad values show maladaptive and antisocial behaviour (e.g. Ellen et al., Citation2019; Krick et al., Citation2016), they can be threatening (e.g. Van Dellen et al., Citation2011) and can, therefore, lead to BIS acttivation and distress (Abdollahi et al., Citation2011; Lüders et al., Citation2016). This threat reaction was also found amongst the coaches of this study, as the coaches reported anxiety and distress after having coached the described client. Thus, the results further display the negative influence of dark triad clients on their coaches.

When it comes to dealing with these clients, the list of successful and unsuccessful strategies are highly varying and contradict each other, making it unclear of what can actually help. Although the results did not provide any clear recommendation of strategies to deal with a dark triad client, a coach’s BAS activation may help the coaching success. Thus, the more approach-motivated a coach is, the better the coach may be able to find the right strategy in dealing with the client. This underlines findings of approach motivation helping people to think of direct and indirect solutions in dealing with the threat (Lüders et al., Citation2016). This BAS activation may deal with self-esteem (Dodgson & Wood, Citation1998; McGregor et al., Citation2009) or self-compassion in terms of self-empathy, common humanity, and mindfulness (Arch et al., Citation2014; Neff, Citation2003).

Limitations

Although the present field study shows important findings about dark triad coaching clients, there are three limitations. First, coaches reported about the client and the coaching success. We were interested in coaches and not the clients themselves, as reports from others can give a great insight (Spain et al., Citation2013). However, the client’s point of view also needs to be assessed in future research. Second, the coaches self-reported retrospectively, which can lead to distortions of perceptions. Thus, future research should accompany ongoing coaching processes with asking both coach and client. A third limitation of this paper is that it was more exploratory with regard to strategies in dealing with dark triad clients. This qualitative attempt depicted several strategies without any quantitative finding on what could actually work, leaving future researchon investigating the actual success of these strategies.

Theoretical implications

This research was the first step to see whether dark triad clients can actually occur as coaching clients and to more qualitatively see what can happen with the coaches in such a situation. However, it would be important to know more about the probability of dark triad clients in coaching. Thus, future research should investigate how high this probability is. Graßmann et al. (Citation2020) found that when being asked about difficulties in coaching per se, coaches still mentioned dark triad traits very frequently. A second theoretical implication is the manipulation of the client in order to see whether BIS and distress occur in an experimental context. Further manipulation studies, in which the client was manipulated (actor/actress) showed similar findings regarding BIS activation and distress (Diller, Stollberg, et al., Citation2020; Schiemann et al., Citation2020). If BAS is activated, direct or indirect solutions can be pursued (Jonas et al., Citation2014). However, BAS activation does not imply the solution that is pursued. Moreover, it seems that there is no ‘right‘ solution for dealing with the client when looking at the divergent results. This finding raises the question of what the success of the strategies depends, implying for future research to consider the circumstances in which the named coaching strategies are effective or ineffective.

Practical implications

When talking about ‘right‘ solutions, the coaches’ ethical responsibility and professional values are important factors (Iordanou et al., Citation2017). Ethical coaching standards should include to openly disclose (potential) conflicts, honour an equitable coach-client-relationship, encourage clients to go to another service (e.g. therapy) if better needed, and only let client set goals and choose methods that are ethically justifiable (International Coach Federation, Citation2016b). One strategy in dealing with dark triad clients is to use mindfulness exercises in order to reduce BIS activation. In our recent studies, we found that coaches that dealt with a narcissistic client had less BIS activation and more BAS activation after a short mindfulness practice of ten minutes (Diller, Stollberg, et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, supervision may be an intervention to help with self-awareness, self-esteem, and self-compassion, as supervision helps the coach to reflect on the coaching process, the client’s behaviour, and the coach’s feelings (Passmore & McGoldrick, Citation2009).

Conclusion

The present study can serve as a starting point for further research that deals generally with difficulties in coaching and specifically with clients of the dark triad. It emerged from the work that dark triad clients do not only occur in coaching but that coaches feel threatened by them, leading to BIS activation and distress. Thus, further research needs to investigate the perceived threat when dealing with clients of the dark triad can be reduced and approach motivation can be fostered.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sandra Julia Diller

Dr Sandra Julia Diller is a Senior Scientist and Senior Lecturer at the Department of Psychology at the University of Salzburg, researching on coaching, mentoring, and mindfulness from a social psychology point of view (see also research affiliation to the Harvard Institute of Coaching). Complementing her research, she has completed programs in coaching education, training education, and mentoring education. Additionally, she is co-responsible for the coaching training and the mentoring training at the University of Salzburg.

Dieter Frey

Professor Dieter Frey is the former head of the Division of Social Psychology at the LMU Munich and the head of the LMU Center for Leadership and People Management. For many years, he has worked as a coach, trainer, and consultant for topics such as leadership, motivation, innovation, and more. He is a member of the Bavarian Academy of Science and has been announced the winner of the German Psychology Award in 1998.

Eva Jonas

Professor Eva Jonas is the head of the Division of Social Psychology at the University of Salzburg. In her research, she focuses on motivated social cognition, researching people’s reactions to threats, the processes involved in social interactions (e.g. advisor–client interactions, fairness), and different development formats (coaching, training, mentoring, supervision). In addition, she is a certified coach and supervisor, and is responsible for further trainings in management, training, coaching, and supervision.

Notes

1 Although all three traits show low levels of agreeableness, low agreeableness cannot be equalised with having high dark triad levels, as people with high dark triad level show also other different aspects (Stead & Fekken, Citation2014).

2 The results do not change when including these nine people, but it is needed to exclude them for the independent variable ‘leadership level’.

3 Controlling for training and the number of clients did not have any influence on the results.

References

- Abdollahi, A., Pyszczynski, T., Maxfield, M., & Luszczynska, A. (2011). Posttraumatic stress reactions as a disruption in anxiety-buffer functioning: Dissociation and responses to mortality salience as predictors of severity of posttraumatic symptoms. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021084

- Agroskin, D., Jonas, E., Klackl, J., & Prentice, M. (2016). Inhibition underlies the effect of high need for closure on cultural closed-mindedness under mortality salience. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 1583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01583

- Arch, J. J., Brown, K. W., Dean, D. J., Landy, L. N., Brown, K. D., & Laudenslager, M. L. (2014). Self-compassion training modulates alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, and subjective responses to social evaluative threat in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 42, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.12.018

- Babiak, P., & Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work. HarperCollins.

- Blair, C. A., Hoffman, B. J., & Helland, K. R. (2008). Narcissism in organizations: A multisource appraisal reflects different perspectives. Human Performance, 21(3), 254–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959280802137705

- Boddy, C. R. P., Ladyshewsky, R., & Galvin, P. (2010). Leaders without ethics in global business: Corporate psychopaths. Journal of Public Affairs, 10(3), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.352

- Cavanagh, M. (2005). Mental-health issues and challenging clients in executive coaching. In M. Cavanagh, A. M. Grant, & T. Kemp (Eds.), Evidence-based coaching: Theory, research and practice from the behavioural sciences (pp. 21–36). Australian Academic Press.

- Corr, P. J. (2004). Reinforcement sensitivity theory and personality. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 28(3), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.01.005

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagnè, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former Eastern Bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(8), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278002

- De Haan, E. (2008). I doubt therefore I coach: Critical moments in coaching practice. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 60(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.60.1.91

- DeSorcy, D. R., Olver, M. E., & Wormith, J. S. (2017). Working alliance and psychopathy. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(7-8), 1739–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517698822

- Diller, S. J., Czibor, A., Szabo, Z. P., Restas, P., Jonas, E., & Frey, D. (2020). The “dark top” and their work attitude: The magnitude of dark triad traits at various leadership levels and their influence on leaders’ self- and other-related work attitude. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Diller, S. J., Stollberg, J., & Jonas, E. (2020). Don’t be scared – be mindful! The effect of a mindfulness intervention after threat. Manuscript in preparation.

- Dodgson, P. G., & Wood, J. V. (1998). Self-esteem and the cognitive accessibility of strengths and weaknesses after failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.178

- Ellen, B. P., Kiewitz, C., Garcia, P. R. J. M., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2019). Dealing with the full-of-self-boss: Interactive effects of supervisor narcissism and subordinate resource management ability on work outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(3), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3666-4

- Gerber, J., & Wheeler, L. (2009). On being rejected: A meta-analysis of experimental research on rejection. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(5), 468–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01158.x

- Giacobbi, P., Withney, J., Roper, R., & Butryn, P. (2002). College coaches’ views about the development of successful athletes: A descriptive exploratory investigation. Journal of Sport Behavior, 25(2), 164–181.

- Graßmann, C., & Schermuly, C. C. (2017). The role of neuroticism and supervision in the relationship between negative effects for clients and novice coaches. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 11(1), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2017.1381755

- Graßmann, C., Schiemann, S. J., & Jonas, E. (2020). Welche Strategien nutzen Coaches bei herausfordernden Klienten? Eine explorative Analyse von Herausforderungen, Strategien und der Rolle von Supervision. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Greif, S. (2017). Hard to evaluate: Coaching services. In A. Schreyögg, & C. Schmidt-Lellek (Eds.), The Professionalization of coaching (pp. 47–68). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-16805-6_3

- Grijalva, E., Harms, P. D., Newman, D. A., Gaddis, B. H., & Fraley, R. C. (2014). Narcissism and leadership: A meta-analytic review of linear and nonlinear relationships. Personnel Psychology, 68(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12072

- Grover, S., & Furnham, A. (2016). Coaching as a developmental intervention in organisations: A systematic review of its effectiveness and the mechanisms underlying it. PLOS ONE, 11(7), e0159137. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159137

- Harms, P. D., Spain, S. M., & Hannah, S. T. (2011). Leader development and the dark side of personality. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(3), 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.007

- International Coach Federation. (2016a). 2016 ICF Global Coaching Study: Executive Summary. Retrieved July 01, 2018, from https://coachfederation.org/app/uploads/2017/12/2016ICFGlobalCoachingStudy_ExecutiveSummary-2.pdf

- International Coach Federation. (2016b). Ethische Standards International Coach Federation (ICF). Retrieved December 3, 2019, from https://www.coachfederation.de/files/icf_ethische_standards_deutsch_2016_02.pdf

- Iordanou, I., Hawley, R., & Iordanou, C. (2017). Values and ethics in coaching. Sage.

- Jonas, E., McGregor, I., Klackl, J., Agroskin, D., Fritsche, I., Holbrook, C., … Quirin, M. (2014). Threat and defense: From anxiety to approach. In J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology: Vol. 49 (pp. 219–286). Elsevier Academic Press.

- Jonason, P. K., Slomski, S., & Partyka, J. (2012). The dark triad at work: How toxic employees get their way. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 449–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.008

- Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L. T., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Kessler Psychological distress scale. PsycTESTS Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/t22929-000

- Kets de Vries, M. F. R., & Rook, C. (2018). Coaching challenging executives. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3099368

- Kilburg, R. R. (2002). Failure and negative outcomes: The taboo topic in executive coaching. In C. Fitzgerald, & J. B. Berger (Eds.), Executive coaching (pp. 283–305). Davies-Black.

- Krick, A., Tresp, S., Vatter, M., Ludwig, A., Wihlenda, M., & Rettenberger, M. (2016). The relationships between the dark triad, the moral judgment level, and the students’ disciplinary choice. Journal of Individual Differences, 37(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000184

- Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2005). Pyschopathy, machiavellianism, and narcissism in the five-factor model and the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1571–1582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j/paid.2004.09.016

- Lüders, A., Jonas, E., Fritsche, I., & Agroskin, D. (2016). Between the lines of us and them: Identity threat, anxious uncertainty, and reactive in-group affirmation: How can antisocial outcomes be prevented? Understanding Peace and Conflict Through Social Identity Theory, 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29869-6_3

- Mathieu, C., Neumann, C. S., Hare, R. D., & Babiak, P. (2014). A dark side of leadership: Corporate psychopathy and its influence on employee well-being and job satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.010

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Retrieved 01, 10, 2018, from: http://nbnresolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

- McClelland, D. C., & Burnham, D. H. (1976). Power is the great motivator. Harvard Business Review, 54, 100–110.

- McGregor, I., Nail, P. R., & Inzlicht, M. (2009). Threat, high self-esteem, and reactive approach-motivation: Electroencephalographic evidence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 1003–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.011

- Murphy, M. (2006). Leadership IQ: Why new hires fail. Public Management, 88(2), 33–37.

- Neff, K. (2003). Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

- O’Boyle, E. H., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). A meta-analysis of the dark triad and work behavior: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 557–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025679

- Oellerich, K. (2016). Negative Effekte von coaching und ihre Ursachen aus der Perspektive der Organisation. Organisationsberatung, Supervision, Coaching, 23(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11613-016-0446-4

- Ogloff, J. D., Wong, S., & Greenwood, M. A. (1990). Treating criminal psychopaths in a therapeutic community program. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 8(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2370080210

- Olver, M. E., & Wong, S. C. P. (2006). Psychopathy, sexual deviance, and recidivism among sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 18(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11194-006-9006-3

- O’Meara, A., Davies, J., & Hammond, S. (2011). The psychometric properties and utility of the short Sadistic Impulse scale (SSIS). Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 523-531. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022400

- Passmore, J., & McGoldrick, S. (2009). Supervision, extravision, or blind faith? A grounded theory study of the efficacy of coaching supervision. International Coaching Psychology Review, 4, 143–159.

- Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Towards a taxonomy of dark personalities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 421–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414547737

- Paulhus, D. L., & Jones, D. N. (2015). Measuring dark personalities via questionnaire. In G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, & G. Matthews (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological constructs (pp. 562–594). Academic Press.

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

- Rosenthal, S. A., & Pittinsky, T. L. (2006). Narcissistic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.005

- Routledge, C., Ostafin, B., Juhl, J., Sedikides, C., Cathey, C., & Liao, J. (2010). Adjusting to death: The effects of self-esteem and mortality salience on well-being, growth motivation, and maladaptive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(6), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021431

- Schermuly, C. C. (2014). Negative effects of coaching for coaches: An explorative study. International Coaching Psychology Review, 9, 167–182.

- Schermuly, C. C., & Bohnhardt, F. A. (2014). Und wer coacht die coaches? Organisationsberatung, Supervision, Coaching, 21(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11613-014-0355-3

- Schiemann, S. J., & Jonas, E. (2020). Striving for power far off from ethics: The “dark triad” traits among executives and the consequences for organizations. Organisationsberatung, Supervision, Coaching, 27(2), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11613-020-00653-9

- Schiemann, S. J., Jutzi, C., Eberhard, I., Mühlberger, C., & Jonas, E. (2020). I don’t like you – I don’t empathize with you! How disliking a client can influence a coach’s empathy. Manuscript discussed at the 16th Workshop on Research Advances in OB (Organizational Behavior) and HRM (Human Resources Management) in Paris, 2019.

- Schuh, S. C., Hernandez Bark, A. S., Van Quaquebeke, N., Hossiep, R., Frieg, P., & Van Dick, R. (2014). Gender differendes in leadership role occupancy: The mediating role of power motivation. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1663-9

- Schyns, B. (2014). Dark personality in the workplace: Introduction to the special issue. Applied Psychology, 64(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12041

- Southard, A. C., Noser, A. E., Pollock, N. C., Mercer, S. H., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2015). The interpersonal nature of dark personality features. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(7), 555–586. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2015.34.7.555

- Spain, S. M., Harms, P., & LeBreton, J. M. (2013). The dark side of personality at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), S41–S60. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1894

- Stead, R., & Fekken, G. C. (2014). Agreeableness at the core of the dark triad of personality. Individual Differences Research, 12(4), 131–141.

- Van Dellen, M. R., Campbell, W. K., Hoyle, R. H., & Brandfield, E. K. (2011). Compensating, resisting, and breaking: A meta-analytic examination of reactions to self-esteem threat. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310372950

- Van den Broeck, A., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C.-H., & Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self- determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1195–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316632058

- Van Dijk, E., & De Cremer, D. (2006). Self-benefiting in the allocation of scarce resources: Leader-follower effects and the moderating effect of social value orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1352–1361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206290338

- Volmer, J., Koch, I. K., & Göritz, A. S. (2017). Corrigendum to ‘The bright and dark sides of leaders’ dark triad traits: Effects on subordinates’ career success and well-being’ [personality and Individual Differences 101 (2016) 413–418]. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 226. https://doi.org/10.2016/j.paid.2016.12.027

- Wallace, H. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2002). The performance of narcissists rises and falls with perceived opportunity for glory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.819