ABSTRACT

Research on the effects of climate change imagery has mainly focused on traditional photographs or infographics, thereby neglecting other visual presentation forms increasingly used in today’s digital landscape. Hence, this study investigates how an immersive 360-degree photograph affects individuals’ knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility when being embedded in text-based climate change coverage. To isolate the modality features driving potential effects, the 360-degree photograph is contrasted with two less immersive visualization forms (video and still photo). News readers’ issue-specific prior knowledge, topic involvement, and level of environmental concern were considered as potential moderators. Results of an online survey experiment (N = 401) reveal detrimental effects for adding 360-degree technology to text-based news on knowledge acquisition and provide no evidence for effects on perceived message credibility. Moreover, the effects do not vary among levels of the three moderators under study. The implications of these limited effects for environmental communication are discussed.

Visual imagery plays a crucial role in providing information about the global challenge of climate change (O’Neill, Citation2017). News stories are frequently augmented with images that emphasize the impact of changing climate conditions, show politicians, protesters, and scientists, or illustrate natural landscapes such as glaciers, forests, or mountains (e.g. DiFrancesco & Young, Citation2011; Metag, Schäfer, Füchslin, Barsuhn, & Kleinen-von Königslöw, Citation2016; O’Neill, Citation2013; Rebich-Hespanha et al., Citation2015). The widespread use of visual elements in mediated climate change communication is supported by research showing that science-related information is better understood when presented in visual form (Taddicken, Citation2013). Moreover, several authors have provided evidence that the way images present specific content can influence the public’s perception of and engagement with climate change (e.g. Chapman, Corner, Webster, & Markowitz, Citation2016; Devine-Wright, Citation2013; Feldman & Hart, Citation2018; Metag et al., Citation2016).

However, although technological advancements are fundamentally changing the presentation and consumption of environmental communication (Wang, Corner, Chapman, & Markowitz, Citation2018), studies on the effects of climate-related imagery have mainly focused on traditional presentation modes such as photographs or infographics. New developments in the presentation of visual content have rather been unnoticed (but see Ahn et al., Citation2016; Herring, VanDyke, Cummins, & Melton, Citation2017). This is particularly noteworthy since digital-born media relying on these developments are a popular source of environmental information (Fletcher, Citation2016; Painter, Citation2016). Moreover, previous studies investigating the effects of climate change visuals have paid only little attention to common barriers of engagement with climate change such as knowledge and message credibility (Lorenzoni, Nicholson-Cole, & Whitmarsh, Citation2007). This study sets out to address this gap by investigating how the use of 360-degree photography in online news affects individuals’ memory for story content and perceptions of message credibility. 360-degree technology is becoming a mainstream feature of digital journalism (López-García, Silva-Rodríguez, & Negreira-Rey, Citation2019). It provides news consumers with an omnidirectional view and enables them to explore a scenery or object on their own by panning or zooming anywhere in the picture. That is, unlike traditional photographs or videos, 360-degree visualizations offer an immersive experience of content, which might influence important outcomes of reading news about climate change.

In order to systematically investigate how immersion alters the understanding and evaluation of a news story, and to isolate the modality features that might drive these effects, this study contrasts the effects of the 360-degree photograph with the effects of two less immersive visualization forms, namely a still photo and a video. By doing so, it extends previous research on content-specific effects of visual representations of climate change by shifting the focus to modality-specific effects. This allows to bring our understanding of mediated climate change communication closer to today’s highly image focused and interactive media environment, and to shed light on a widely understudied research area. In addition, this study follows the notion that individuals capture the meaning of an image by engaging in a decoding process that is driven by both, stimulus properties of the visual and individual predispositions (Geise & Baden, Citation2014). To make informed statements also about harder-to-reach audiences, individuals’ issue-specific prior knowledge, involvement in the topic of climate change, and level of environmental concern (Lee & Kim, Citation2016) are incorporated as potential moderators. Hence, while complementing prior work on effects of visual climate change communication (Hansen & Machin, Citation2013), this study offers practical insights for news organizations and climate change advocates on how to use an innovative technology of today’s digital environment to effectively report about a complex topic in a way that connects with members of a non-expert audience.

360-degree photography as immersive media

360-degree photography refers to user-controlled omnidirectional photographs that enable the viewer to freely explore the entire environment around the camera by clicking and pointing on the image in order to drag it in the desired direction. 360-degree photographs provide individuals with a seamless first-person experience of a scenery or object, aiming to replicate the experience of being at the original point from which the picture was taken. Put in theoretical terms, 360-degree photography is conceptualized as immersive media, with immersion being defined as a property of the technological system used to present the mediated content (i.e. system immersion; Slater, Citation2003). According to Steuer (Citation1992), communication technologies vary across two major dimensions: vividness and interactivity. Vividness hereby denotes the representational richness of the medium, that is, how many different senses the medium can engage (“sensory breadth”) and how realistic these sensory impressions are (“sensory depth”). Interactivity denotes the number and quality of actions users can take in order to modify the form and content of a mediated environment in real time (i.e. user control; Sundar, Citation2008). Following this logic, immersion can be conceptualized as a continuum from low to high, with different visual modalities representing different levels of immersion based on their degree of vividness and interactivity offered. Still photographs, for example, score low in both, vividness and interactivity, as they simply provide a static portrayal of a scenery or object. Videos also score low in interactivity but employ animation and movement, which adds to the depth of the sensory information and generates a more vivid display of the content. 360-degree technology enhances the immersive quality of content even further by enabling users to drag a picture in every direction, instantaneously altering the mediated environment. Engaging with a 360-degree image therefore not only involves interactivity but the interactive feature allows users to seamlessly rotate the angle of the picture, which contributes to the representational richness of the content and thus creates greater vividness. Hence, a 360-degree photograph is considered as being more immersive than a traditional video and, lastly, a still photograph.Footnote1 It might therefore deliver a more conscious feeling of being part of the virtual world and enable the viewers to mentally construct a spatial model of the content in which they can immediately place themselves (Ahn, Bailenson, & Park, Citation2014).

Empirical studies on pro-environmental attitudes and behavior have demonstrated that immersive media can indeed initiate a deeper processing of information, which then leads to positive persuasion effects. Ahn et al. (Citation2016), for example, found that simulations that enable individuals to inhabit the body of animals by mimicking their sensory-rich experience in a virtual world increased individuals’ perceived imminence of the environmental risk and thus their level of issue involvement. However, it needs to be taken into account that these studies focused on experiences in immersive virtual environments, conveyed via head-mounted displays or virtual reality headsets. In the present study, a more convenient application of immersive media is investigated, namely 360-degree photography when being used as an add-on to a traditional text-based online news article. Consequently, the promising effects of immersive technology for environmental communication reported in virtual reality literature might not be directly transferrable to the practice of digital journalism.

The interplay of 360-degree photography and text in online news

Effects on information processing and knowledge acquisition

This study takes a limited capacity information processing perspective (Lang, Citation2000) to explain how 360-degree photography may affect individuals’ engagement with the content of a text-based news article. In its basic form, the limited capacity model defines news consumption as a process that involves the allocation of a limited pool of cognitive resources to the simultaneous operation of encoding, storing and retrieving information. The amount of information that is successfully stored in memory is determined by the balance between allocated and required resources: when the demand on resource allocation exceeds the available reserve, a state of cognitive overload occurs, and the message is not processed completely.

Within this theoretical perspective, immersive media such as 360-degree photographs are viewed as complex stimuli that are difficult for individuals to encode, thereby tying up their limited cognitive resources and leaving insufficient capacities for the storage and retrieval of information (Xu & Sundar, Citation2016). Following Bucy (Citation2004), it is assumed that enabling recipients to freely explore an omnidirectional shot generates higher levels of involvement, but at the same time over-stimulates the human information processing system. This might be especially true if the photograph displays content that is interesting but not relevant for understanding the storyline, as it guides individuals’ selective attention away from the main content and confuses their expectation what the story is actually about (Harp & Mayer, Citation1998; see also Lang, Citation1995). Recent experimental research corroborates this view, showing that 360-degree technology experienced on a laptop is rather distracting from than supporting a story (Van Damme, All, De Marez, & Van Leuven, Citation2018), demanding considerable cognitive costs (Sundar, Kang, & Oprean, Citation2017).

The limited capacity model, however, also states that complex stimuli can increase memory for story content by causing an orienting response in news consumers that automatically shifts their attention to the stimulus and elicits additional cognitive resources to the encoding and storing of information (Lang, Bradley, Park, Shin, & Chung, Citation2006; Lang, Bolls, Potter, & Kawahara, Citation1999). Moreover, an interactive 360-degree experience provides a rich mental representation of the content and allows individuals to adjust the pace of information acquisition according to their abilities and needs, which makes cognitive overload less likely to occur. In addition, research in the framework of user engagement (Oh, Bellur, & Sundar, Citation2018; O’Brien & Cairns, Citation2016) and emotional design (Heidig, Müller, & Reichelt, Citation2015) suggests that vivid forms of visual representation evoke positive emotions that might at least compensate for the distraction effect, enhance information processing, and, ultimately, lead to better learning outcomes (Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2018). Given the above, 360-degree technology included in media coverage about climate change can amplify both positive and negative effects of visual elements on knowledge acquisition, which leads to the following research question:

RQ1: How would adding a 360-degree photograph to a text-based news article affect individuals’ acquisition of knowledge?

Effects on perceived message credibility

Although traditional approaches have hypothesized that credibility judgments are determined by an effortful processing of the content, several studies have consistently shown that people rarely base the believability and trustworthiness of online information on a systematic evaluation of the content. Instead, surface characteristics such as the visual appearance, usability, and navigability of a website appear to be among the main drivers of message credibility on the internet (Metzger, Flanagin, & Medders, Citation2010) – at least in the beginning of the reception process (Wathen & Burkell, Citation2002). These findings are in line with information processing theories postulating that individuals are not always able to act in a perfectly rational way, but “must arrive at their inferences using realistic amounts of time, information, and computational resources” (Gigerenzer & Todd, Citation1999, p. 24). One strategy to save mental effort and time while browsing the internet is the use of cognitive heuristics.

Sundar (Citation2008) has proposed a model by which simple cues on websites can trigger specific cognitive heuristics that lead users to snap judgments about the quality of the site and its content. According to this model, embedding a still photograph in a text-based news article could evoke an “old media” perception as it resembles the layout of a traditional newspaper, with generally positive consequences for credibility judgments. Incorporating more advanced and vivid forms of visualizations such as 360-degree photographs, however, might lead news consumers to divergent evaluations. As a spherical view of the camera’s surroundings approximates physical reality more closely, they could trigger the basic rule of “seeing is believing” (Sundar et al., Citation2017). However, a compelling news experience might promote the positive impression of “novelty” or “coolness” just as well as the negative association of “all flash and no substance” (Sundar, Citation2008, p. 82). Empirical evidence so far supports both notions (Horning, Citation2017; Sundar, Jia, Waddell, & Huang, Citation2015). de Haan, Kruikemeier, Lecheler, Smit, and van der Nat (Citation2017), for example, found that information visualizations only add value for news consumers when they are not merely attractive but serve a clear purpose for the storyline. In a similar vein, Oyibo, Adaji, Orji, and Vassileva (Citation2018) demonstrated that perceived credibility of online information is more strongly influenced by features pertaining to classical aesthetics (i.e. cleanness, clarity, and simplicity) than by features pertaining to expressive aesthetics (i.e. richness, novelty, and sophistication; Lavie & Tractinsky, Citation2004).

Regarding the tactile aspect inherent in 360-degree technology, prior research has demonstrated that interactivity affects audiences’ evaluation of web content (Sundar, Bellur, Oh, Xu, & Jia, Citation2014). In the context of online news, it has been demonstrated that the relationship between increased modality (i.e. the combined presentation of text, pictures, and videos) and credibility is shaped by the conscious use of these modalities. This finding suggests that the mere presence of pictures, animation, or sound in a news article might not be sufficient; instead, individuals need to actively engage with an interface to assess the underlying content as more credible (Kiousis, Citation2006). As interactive visualizations have been shown to consume a considerable amount of cognitive resources (Xu & Sundar, Citation2016), it is also possible that they promote the credibility of information by inhibiting a thorough evaluation of the actual content (Slater & Rouner, Citation2002). However, adding additional layers of modality can also impede the positive judgment of media messages (Tran, Citation2015), indicating a curvilinear or ceiling effect. In sum, immersive climate change imagery has the potential to transfer positive as well as negative assessments of the presentation mode to the quality of the content conveyed. Drawing on the literature discussed above, the following research question is proposed:

RQ2: How would adding a 360-degree photograph to a text-based news article affect individuals’ perception of message credibility?

Potential moderators: prior knowledge, topic involvement, and environmental concern

The perception and interpretation of an image is a reciprocal process between the recipient and the image (Geise & Baden, Citation2014). Immersive climate change photography does therefore not necessarily affect all members of the audience in the same way, but its impact might depend on individual factors such as the ability and motivation to invest cognitive resources into the processing and evaluation of a message. Drawing on dual processing models (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986), it is argued that audiences who are either less involved in or knowledgeable about a topic are more likely to rely on a fast mode of processing that requires minimal cognitive effort and therefore to be affected by the “bells and whistles” of an interface (Lee & Kim, Citation2016).

Prior knowledge has been found to determine the extent to which an individual is capable of thoroughly processing incoming information (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). While visual stimuli are usually processed in an automatic, subconscious, and effortless manner (Sojka & Giese, Citation2006; but see Powell, Boomgaarden, De Swert, & de Vreese, Citation2018 for more nuanced notions), dominant visual cues that draw less knowledgeable news consumers into an immersive experience of content might place considerable demands on their processing system, leaving less resources to further attend the surrounding text-based article. This assumption is supported by eye-tracking data, indicating that those with low working memory capacity attend seductive illustrations more often and for longer time spans compared to those with high working memory capacity (Sanchez & Wiley, Citation2006). Similarly, studies in cognitive psychology have found that individuals with a more fragmented knowledge base have difficulties in distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant information (Cook, Citation2006), and in coordinating elements across textual and visual representations (Kozma, Citation2003).

Besides individuals’ level of prior knowledge, a central argument of dual-processing research is that expending cognitive effort and resources to carefully process the message outweighs associated time and energy constrains only if the information is encountered of significant personal importance (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). That is, those indicating not to be intrinsically motivated to read an article about climate change will be more likely to focus on the immersive visual add-on rather than on the text-based content (Lee & Kim, Citation2016). Indeed, studies in the context of science and environmental communication show that involvement (i.e. concern and interest) in the focal topic is a key driver of knowledge acquisition (Falk, Storksdieck, & Dierking, Citation2007; Taddicken, Citation2013). These considerations lead to the expectation that adding 360-degree photography to a text-based news article will mainly exert effects on low-involved and low-knowledgeable news consumers. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: The effect of adding a 360-degree photograph to a text-based news article on (1) knowledge acquisition and (2) perceived message credibility will be more pronounced among individuals with low levels of (a) prior knowledge, (b) involvement in the topic of climate change, or (c) environmental concern.

Methods

To systematically investigate effects of 360-degree photography in climate change coverage, an online survey experiment among 401 Austrian citizens was conducted. In a between-subjects design, individuals were randomly assigned to one of four conditions and presented with a short realistic news item on the causes and consequences of a potential disruption of the Gulf Stream current, including either a 360-degree photograph (“360-degree condition”; n = 102), a short video (“video condition,” n = 98), a still photograph (“photo condition”; n = 100), or plain text (“text-only condition,” n = 101). This procedure allows to compare the effects of three visual presentation forms that vary in their relative level of immersion – ranging from low (still photograph) to high immersion (360-degree photograph), with the video scoring in the middle – and thus to systematically investigate how immersion alters the understanding and evaluation of a news story. Moreover, it allows to isolate the modality features that determine the respective level of immersion and therefore might drive these effects.

Sample and procedure

This study employs data from a national online panel pool administered by the Austrian market research company MindTake. Participants were recruited based on a stratified quota sampling method, resembling the Austrian population aged 18–65 in terms of age, gender, and formal education. This sampling strategy ensures sufficient variation in the moderating variables level of prior knowledge, topic involvement, and environmental concern. Initially, a total of 404 individuals participated in the survey. Three participants were excluded due to technical problems, which leaves us with a final sample of 401 respondents (52% females; mean age = 41.5, SD = 12.7). The data was collected in October 2017.

The procedure of the online survey experiment is as follows. First, after signing a consent form, all respondents completed a short pre-test questionnaire, including possible moderators of the main effects, with items measuring the level of prior knowledge, involvement in the topic of climate change, and environmental concern. Then, participants read an online news article in which the visual content was manipulated so as to contain either a 360-degree photograph, a short video, a still photograph, or no visualization. Third, participants received a post-test questionnaire asking for the perceived credibility of the stimulus article as well as measuring knowledge gain. Finally, after the post-test, all participants were debriefed: they were informed about the experimental design and the main intentions of the study. A between-condition randomization check on age, gender, educational background, and web experience performed at the outset of the analysis revealed successful randomization with no between-group differences (p > .05). In addition, the three experimental groups did not differ in terms of the three potential moderators (p > .05).

Stimulus material

The stimulus material consisted of one news article per condition. After a general explanation of how the Gulf Stream helps regulating European climate, the article reports on competing theories on whether and how the circulation of the Atlantic Ocean could lose its strength and discusses potential ecological and economic implications of even minor disruptions in the Gulf Stream current for Europe. Claims are made with reference to existing scientific representatives or institutions. The topic of the article represents common characteristics of mediated climate change communication such as an abstract problem located in the distant future with nevertheless far-reaching consequences for the home region of the recipients, and controversial empirical evidence presented by international scientists. Moreover, the article combines a niche aspect of the climate change debate with general information on ocean currents. It is thus assumed that participants may have some prior knowledge about the topic with which the information presented in the stimulus could be integrated (Eurobarometer, Citation2009). Finally, it was not a salient topic at the time of data collection, which prevents actual media coverage from interfering with the experiment. The newsworthiness of the topic is nevertheless plausible, as the prospect of the Gulf Stream slowing down or even stopping is still under scientific debate (Hutsteiner, Citation2018).

As this study is concerned with modality-specific features of 360-degree photography, the article was accompanied by a general image, namely an aerial panorama photograph of a snowy landscape on which the Austrian flag is placed (see Appendix A for a screenshot of the stimulus image). This image serves the purpose of the study very well: It illustrates the impact of a weakened Gulf Stream on European climate (i.e. a cooling down of temperatures that would turn the continent into a desert of snow and ice), while speaking to the specific audience of the stimulus article (i.e. Austrian-based news consumers), without offering additional information that is necessary to understand the text-based story. The latter is particularly important for the 360-degree condition, where users might engage only with a limited area of the visualization. It further allows to run the statistical models with only those participants who remembered seeing the Austrian flag in the 360-degree picture and the video, and thus indeed attended the respective visual presentation form.

To secure a high amount of experimental control, the stimulus article was created based on several news reports on a potential weakening of the Gulf Stream published in German quality newspapers. Moreover, the article was given the length and structure of a traditional online news article (average time spent with the article = 3.5 min), and used a panoramic image shot by a professional photographer as stimulus picture to further achieve realistic experimental conditions.Footnote2 To ensure comparability, the layout and content of the stimulus article was the same across all conditions, created and conveyed via WordPress. The written text was identical in all four groups as the manipulation only affects the visualization inserted in the second half of the article. Specifically, for the photo condition, the textual news article was augmented with the aerial panorama picture presented as a still photograph. In the corresponding 360-degree condition, the same picture was displayed using the VRView application in WordPress to enable participants an interactive, 360-degree viewing experience by navigating the picture in all directions via mouse-based actions. For the video condition, the screen was recorded while the author was interacting with this 360-degree photograph. The resulting video takes 16 s. The still photograph, the video, and the 360-degree photograph were matched for size and placement in the story. For the control condition, no visualization was used, but all information was presented in plain text form.

Measures

Dependent variables

The first dependent variable, knowledge acquisition, was a direct measure of the amount of information participants could remember after reading the stimulus article. In line with prior research (e.g. Lang, Citation2000), it included two different sets of questions that tap different types of memory: first, a multiple choice quiz with five questions assessing recognition memory (e.g. “What does the article say – why can’t scientists predict exactly how the ocean currents will develop in the future?”), and second, four open-ended questions assessing cued recall (e.g. “According to the article, how many years will it at least take before the next ice age begins”; or “The article cited several reasons for the weakening of the Gulf Stream. Please name one of them and explain it briefly”). Altogether, the nine questions referred to information mentioned in the stimulus article. Participants were encouraged to click or note “I don’t know” if they could not remember the information. While questions concerning recognition were dummy coded (i.e. correct = 1 vs. incorrect or “don’t know” = 0), Mayer’s (Citation1985) concept of “idea units” was employed to measure information recall and to code the open answers. A complete open-ended answer consisted of no more than three idea units, with one idea unit being defined as a word or phrase denoting a single action or event.Footnote3 A complete answer was coded as 1, but participants earned partial points for each correct unit mentioned. For subsequent data analysis, the coding of the recall and recognition measure was combined to form a sum index of knowledge acquisition (M = 3.6, SD = 2.0, theoretical range = 0 to 9).

Following prior research in this area (Schweiger, Citation1999), the second dependent variable, perceived message credibility, was assessed using a semantic differential with ten items measuring participants’ perceptions of the believability, accuracy, trustworthiness, bias, and completeness of the information provided in the stimulus article. All items were measured on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The mean value of the ten items constituted the final perceived message credibility measure (M = 3.8, SD = 0.7, Cronbach’s α = 0.9).

Moderators

Prior knowledge was measured by a quiz assessing participants’ factual knowledge about climate change. To avoid design effects, only five out of the nine questions in the quiz referred to global warming, ocean water, and its movement. Participants were offered a “don’t know” option for each question. In order to create a sum index across the five relevant questions, correct answers were coded as 1, wrong answers – including “don’t know” – as 0 (M = 3.1, SD = 1.2, theoretical range = 0–5). To measure involvement in the topic of climate change, a four-item scale was created, assessing whether for the participants personally, the topic of climate change is (1) interesting, (2) important, (3) useful, and (4) whether they would like to get more information about it. The items were measured on a 5-point scale and summarized in a mean index (M = 3.9, SD = 0.8; Cronbach’s α = .89). Finally, a battery of seven items adapted from Preisendörfer (Citation1999) was used to measure participants’ level of environmental concern. The items comprised statements such as “It worries me when I think about the environmental conditions in which our children and grandkids are likely to live.” or “The significance of climate change is greatly exaggerated (reverse coded).” They were measured on a 5-point scale and summarized in a mean index (M = 3.8, SD = 0.7, Cronbach’s α = .75). All three moderator variables appeared in the pretest to ensure that they are not affected by the experimental manipulations.

Results

Main effects on knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility

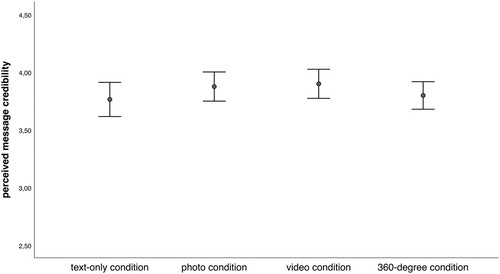

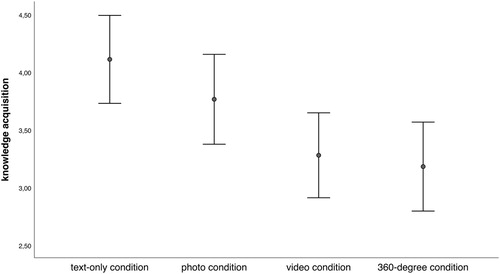

To examine how a 360-degree photograph directly affects news consumers’ knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility, a series of ANCOVA models was run, including participants’ exposure time as covariate.Footnote4 The first model tested for effects on knowledge acquisition, revealing a significant overall effect for adding a visual element to a text-based news article, F(3, 396) = 5.1, p < .01, partial η2 = .04. A post hoc test with Bonferroni correction showed that it was the difference between the text-only condition and the 360-degree condition as well as the difference between the text-only condition and the video condition that reached significance at a 95% probability level. Participants who were exposed to a news article including 360-degree technology, however, learned less than those who were exposed to the same information in plain text form (RQ1), with a mean difference of 0.9 (Mtext = 4.1, M360-degree = 3.2, see also ). The same direction of effect was found for the video condition, with a mean difference of 0.8 (Mtext = 4.1; Mvideo = 3.3). Participants who were exposed to the traditional photograph reported a higher mean level of knowledge acquisition than those who were exposed to the video or 360-degree photograph (see also ). The post hoc test, however, revealed no significant differences between the photo condition and all other conditions (p > .05). In order to provide a more detailed account of participants’ overall cognitive performance, additional models were run including recognition and cued recall as separate dependent variables. The effects appear to be comparable to those on the combined knowledge measure. However, for recognition memory, the negative effect of adding a video to a written text is not significant (p = .07; see Appendix C for mean differences and results of the Bonferroni post-hoc test).

Figure 1. Main effects on knowledge acquisition.

Note: Values are estimated marginal means (95% CI) for each condition. Analysis controlled for exposure time.

The second model tested for effects on perceived message credibility, finding no support for the assumption that visual elements might enhance news consumers’ perception of the believability, accuracy, and trustworthiness of media coverage about climate change (RQ2), F(3, 396) = .89, p > .05, partial η2 = .01. Participants who read the article as a text-only version reported equal credibility ratings than did those in the three visual conditions (Mtext = 3.8; Mstatic = 3.9, Mvideo = 3.9; M360-degree = 3.8). That is, neither visual content in general, nor still photography, video, nor 360-degree photography in particular enhanced participants’ perception of the believability of the message (see also ).

Conditional effects on knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility

Given the theoretical importance of issue involvement and prior knowledge for psychological effects of media processing (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986), this study further tested for conditional effects of the different types of imagery under study (H1). Specifically, moderation analyses for knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility were conducted, with prior knowledge, involvement in the topic of climate change, and environmental concern being included as single moderators in the model.Footnote5 However, overall, no significant interactions emerged (p > .05). That is, for all four presentation forms (text-only vs. traditional photo vs. video vs. 360-degree photography), the participants’ level of prior knowledge, topic involvement and environmental concern did not influence their relationship with knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility.

Discussion

This study investigated whether and how adding a 360-degree photograph to a text-based news article might affect knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility of news consumers, with a special focus on individuals with different levels of prior knowledge, topic involvement, and environmental concern. Overall, the effects are less pronounced than expected. As information processing research supports both, evidence for a beneficial as well as a detrimental effect on individuals’ memory for story content and perceived message credibility, no clear assumption was made upfront about the impact of 360-degree photography in text-based climate change news. Regarding memory for story content, the results point to the latter: participants reported significantly lower levels of knowledge acquisition after reading a news text including a 360-degree photograph than after reading text alone. This finding indicates that the immersive image served as a distractor, seducing news consumers’ attention away from the actual story (Van Damme et al., Citation2018), and depriving them of cognitive resources they would have needed to thoroughly attend, process, and store the information presented in the accompanying news article (Xu & Sundar, Citation2016). Since dragging around an omnidirectional image is considered a rather easy task, it is plausible that participants might had enough mental resources left for storing information (Boksem, Meijman, & Lorist, Citation2005), but simply lacked the motivation to carefully attend them. Even though there is no moderation of issue involvement and environmental concern, the costs might have outweighed the benefits of engaging with both, the immersive and non-immersive (text-based) parts of the stimulus article. That is, contrary to assumptions of user engagement and emotional design theories (Heidig et al., Citation2015; Oh et al., Citation2018), the immersive technology does not appear to have resulted in enhanced levels of enjoyment that are translated into a more efficient processing of information. Instead, the 360-degree photograph failed to elicit an automatic or controlled allocation of cognitive resources (Lang et al., Citation2006). One possible explanation for this result is the content of the stimulus image – a panorama photograph of a snowy landscape on which the Austrian flag is placed. It might be the case that this specific image was not perceived as attractive enough to promote intense affective responses, as snowy landscapes are quite a common trope in climate change coverage (O’Neill, Citation2013). An empirical examination of emotional reactions to immersive climate change images would, however, be desirable. For climate change communication, these findings imply that pairing a news article with an immersive visualization that delivers no relevant information might be a risk, as it appears to serve as a distractor. Future studies may opt for a different research design with immersive visualizations conveying relevant messages to investigate their influence on knowledge acquisition.

In order to get a clearer picture of the unique contribution of 360-degree photography to news consumers’ memory for story content and perceived message credibility, it was contrasted with two less immersive visual forms, namely a still photo and a video. Interestingly, the video is found to affect the overall cognitive performance in the same negative fashion as the 360-degree image. When distinguishing between recognition and cued recall as two different types of memory, however, for the video condition, this effect is only significant for cued recall, which means that information was successfully encoded but not stored in memory (Lang, Citation2000). These findings indicate that the detrimental effect on learning cannot be solely attributed to the unique combination of vividness and interactivity entailed in 360-degree technology. Instead, providing individuals with a non-interactive representation of content entailing animation and movement might have already resulted in incomplete information processing. Adding a traditional photo to the text, however, did neither help nor hinder learning. An extension of this study could consider the interplay of interactivity and vividness to better understand what it is about immersive technologies that drives the effects. Moreover, assuming that participants spent more time with the video and the 360-degree image than with the still image, these more immersive presentation forms might have tempted them to a superficial processing of the rest of the article, falsely replacing the associated text as the main information source. Future studies are thus encouraged to supplement the standard measures applied in this study with eye-tracking techniques or thought listing tasks to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms at work when people read, view, and interact with a contemporary news article about climate change.

In addition, immersive presentation forms in visual climate change communication merit more detailed investigation. In particular, it would be interesting to see whether the negative effect suggested by the data in this study is reproducible with other types of immersive visualizations such as interactive 3D models in order to address the question of how best to design innovative presentation forms that engage audiences with environmental messages and may even promote attitudinal or behavioral changes. Moreover, additional work is required to link modality-specific effects to content-specific effects of visual climate change communication found in prior research, and to systematically investigate their interrelation.

Regarding perceived message credibility, no significant direct or conditional effects were found. Contrary to existing theory, specific characteristics of the visual elements did not translate into higher credibility ratings (Sundar, Citation2008). Individuals perceived a news article as equally accurate, believable, and trustworthy, whether it was presented in text-only form, or included a more or less immersive visualization. This finding calls for further research as it might be the case that for science-related news, visual elements need to provide some kind of factual evidence for the information provided (e.g. a picture of a scientist mentioned in the text), while the stimulus pictures in this study served rather decorative functions. For 360-degree photography, it is also possible that potential positive responses to the technology (e.g. senses of appeal) were canceled out by simultaneous negative responses (e.g. senses of “all flash no substance,” Sundar Citation2008). Moreover, while it is usually expected that low-knowledgeable and low-involved audiences respond differently to media coverage than their high-knowledgeable and high-involved counterparts, this was not the case in the present study. However, as the experiment was conducted online, there was no control over how the study participants attended the textual and visual parts of the stimulus article. When running the models with a more restrictive sample that only includes those participants who remembered seeing the Austrian flag in the 360-degree picture and the video, the results did not substantially change, indicating that the non-significant findings are not due to the non-use of the image.

Despite these limitations, this study represents a first step to bring research on climate change coverage closer to the increasingly non-traditional online news environment, where innovative presentation forms such as 360-degree photography have become mainstream features. Moreover, as prior research on psychological effects of visual climate change communication was mainly concerned with changes in attitudes and issue importance, it adds insights about two key outcome variables to the media effects literature in the context of environmental communication. Hence, the findings of this study carry potentially important implications, informing our theoretical understanding of the power of immersion in media coverage about climate change as well as supporting the ability of media practitioners and climate change advocates to effectively communicate complex and controversial news to a broad, non-expert audience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 This gradation represents the relative immersiveness between the different visual modalities. It could be extended up to 360-degree videos watched with a head-mounted virtual reality device that enables users to virtually enter the story by shutting out the physical world and allowing for interactivity by natural movements (instead of using a touchpad or mouse).

2 All participants were asked to rate the professionalism of the stimulus article on a five-point scale (1 = unprofessional, 5 = professional). Results indicate high professionalism across all conditions (M360-degree = 3.8; Mvideo = 3.8; Mphoto = 3.7, Mtext = 3.5, p > .05).

3 For example, the answer to the question “In Northern Europe, the salinity of the ocean current increases. Why is that?” consists of three idea units mentioned in the stimulus text, namely (1) the Gulf Stream radiates heat (2), the water cools down, and (3) the water evaporates.

4 The results do not substantially differ when relying on simple ANOVA models. For knowledge: F(3, 397) = 5.1, p = .002. For credibility: F(3, 397) = 0.935, p = .42. See Appendix B for mean differences and results of the Bonferroni post-hoc test.

5 The moderation analyses for knowledge acquisition and perceived message credibility were run three times each, including either prior knowledge, involvement in the topic of climate change, or environmental concern as moderator. The results do not substantially change when I include them simultaneously in one model or apply one as moderator and the remaining two as covariates (i.e., no interaction effects in all models, p > .05).

References

- Ahn, S. J., Bostick, J., Ogle, E., Nowak, K. L., McGillicuddy, K. T., & Bailenson, J. N. (2016). Experiencing nature: Embodying animals in immersive virtual environments increases inclusion of nature in self and involvement with nature. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(6), 399–419.

- Ahn, S. J. G., Bailenson, J. N., & Park, D. (2014). Short-and long-term effects of embodied experiences in immersive virtual environments on environmental locus of control and behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 235–245.

- Boksem, M. A., Meijman, T. F., & Lorist, M. M. (2005). Effects of mental fatigue on attention: An ERP study. Cognitive Brain Research, 25(1), 107–116.

- Bucy, E. P. (2004). The interactivity paradox: Closer to the news but confused. In E. P. Bucy & J. E. Newhagen (Eds.), Media access: Social and psychological dimensions of new technology use (pp. 47–72). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Chapman, D. A., Corner, A., Webster, R., & Markowitz, E. M. (2016). Climate visuals: A mixed methods investigation of public perceptions of climate images in three countries. Global Environmental Change, 41, 172–182.

- Cook, M. P. (2006). Visual representations in science education: The influence of prior knowledge and cognitive load theory on instructional design principles. Science Education, 90(6), 1073–1091.

- de Haan, Y., Kruikemeier, S., Lecheler, S., Smit, G., & van der Nat, R. (2017). When does an infographic say more than a thousand words? Audience evaluations of news visualizations. Journalism Studies. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1267592

- Devine-Wright, P. (2013). Think global, act local? The relevance of place attachments and place identities in a climate changed world. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 61–69.

- DiFrancesco, A. D., & Young, N. (2011). Seeing climate change: The visual construction of global warming in Canadian national print media. Cultural Geographies, 18(4), 517–536.

- Eurobarometer, S. (2009). Europeans’ attitudes towards climate change. (Special Eurobarometer No. 313). Brussels.

- Falk, J. H., Storksdieck, M., & Dierking, L. D. (2007). Investigating public science interest and understanding: Evidence for the importance of free-choice learning. Public Understanding of Science, 16(4), 455–469.

- Feldman, L., & Hart, P. S. (2018). Is there any hope? How climate change news imagery and text influence audience emotions and support for climate mitigation policies. Risk Analysis, 38(3), 585–602.

- Fletcher, R. (2016). The public and news about the environment. In J. Painter (Ed.), Something old, something new: Digital media and the coverage of climate change (pp. 24–36). Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Geise, S., & Baden, C. (2014). Putting the image back into the frame: Modeling the linkage between visual communication and frame-processing theory. Communication Theory, 25(1), 46–69.

- Gigerenzer, G., & Todd, P. M. (1999). Simple heuristics that make us smart. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Greussing, E., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2018). Simply bells and whistles? Cognitive effects of visual aesthetics in digital longforms. Digital Journalism. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2018.1488598

- Hansen, A., & Machin, D. (2013). Researching visual environmental communication. Environmental Communication, 7(2), 151–168.

- Harp, S. F., & Mayer, R. E. (1998). How seductive details do their damage: A theory of cognitive interest in science learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 414–434.

- Heidig, S., Müller, J., & Reichelt, M. (2015). Emotional design in multimedia learning: Differentiation on relevant design features and their effects on emotions and learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 81–95.

- Herring, J., VanDyke, M. S., Cummins, R. G., & Melton, F. (2017). Communicating local climate risks online through an interactive data visualization. Environmental Communication, 11(1), 90–105.

- Horning, M. A. (2017). Interacting with news: Exploring the effects of modality and perceived responsiveness and control on news source credibility and enjoyment among second screen viewers. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 273–283.

- Hutsteiner, R. (2018, April 11). Golfstrom wird schwächer. ORF Online. Retrieved from https://science.orf.at/stories/2906395/

- Kiousis, S. (2006). Exploring the impact of modality on perceptions of credibility for online news stories. Journalism Studies, 7(2), 348–359.

- Kozma, R. (2003). The material features of multiple representations and their cognitive and social affordances for science understanding. Learning and Instruction, 13(2), 205–226.

- Lang, A. (1995). Defining audio/video redundancy from a limited-capacity information processing perspective. Communication Research, 22(1), 86–115.

- Lang, A. (2000). The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication, 50(1), 46–70.

- Lang, A., Bolls, P., Potter, R. F., & Kawahara, K. (1999). The effects of production pacing and arousing content on the information processing of television messages. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 43(4), 451–475.

- Lang, A., Bradley, S. D., Park, B., Shin, M., & Chung, Y. (2006). Parsing the resource pie: Using STRTs to measure attention to mediated messages. Media Psychology, 8(4), 369–394.

- Lavie, T., & Tractinsky, N. (2004). Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of web sites. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 60(3), 269–298.

- Lee, E. J., & Kim, Y. W. (2016). Effects of infographics on news elaboration, acquisition, and evaluation: Prior knowledge and issue involvement as moderators. New Media & Society, 18(8), 1579–1598.

- López-García, X., Silva-Rodríguez, A., & Negreira-Rey, M. C. (2019). Laboratory journalism. In M. Túñez-López, V.-A. Martínez-Fernández, X. López-García, X. Rúas-Araújo, & F. Campos-Freire (Eds.), Communication: Innovation & quality (pp. 147–162). Cham: Springer.

- Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2007). Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change, 17(3-4), 445–459.

- Mayer, R. E. (1985). How to analyze science prose. In B. K. Britton, & J. B. Black (Eds.), Understanding expository text: A theoretical and practical handbook for analyzing explanatory text (pp. 305–313). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Metag, J., Schäfer, M. S., Füchslin, T., Barsuhn, T., & Kleinen-von Königslöw, K. (2016). Perceptions of climate change imagery: Evoked salience and self-efficacy in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Science Communication, 38(2), 197–227.

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 413–439.

- O’Brien, H., & Cairns, P. (Eds.). (2016). Why engagement matters: Cross-disciplinary perspectives of user engagement in digital media. Cham: Springer.

- Oh, J., Bellur, S., & Sundar, S. S. (2018). Clicking, assessing, immersing, and sharing: An empirical model of user engagement with interactive media. Communication Research, 45(5), 737–763.

- O’Neill, S. J. (2013). Image matters: Climate change imagery in US, UK and Australian newspapers. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 49, 10–19.

- O’Neill, S. J. (2017). Engaging with climate change imagery. In Oxford encyclopedia of climate change communication. Oxford, England: Oxford Research Encyclopedias. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.371

- Oyibo, K., Adaji, I., Orji, R., & Vassileva, J. (2018, July). What drives the perceived credibility of mobile websites: Classical or expressive aesthetics? In International conference on human-computer interaction (pp. 576–594). Cham: Springer.

- Painter, J. (2016). New players and the search to be different. In J. Painter (Ed.), Something old, something new: Digital media and the coverage of climate change (pp. 8–23). Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion (pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Springer.

- Powell, T. E., Boomgaarden, H. G., De Swert, K., & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). Framing fast and slow: A dual processing account of multimodal framing effects. Media Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2018.1476891

- Preisendörfer, P. (1999). Konzeptualisierung und Messung des Umweltbewußtseins. In Umwelteinstellungen und Umweltverhalten in Deutschland (pp. 42–55). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Rebich-Hespanha, S., Rice, R. E., Montello, D. R., Retzloff, S., Tien, S., & Hespanha, J. P. (2015). Image themes and frames in US print news stories about climate change. Environmental Communication, 9(4), 491–519.

- Sanchez, C. A., & Wiley, J. (2006). An examination of the seductive details effect in terms of working memory capacity. Memory & Cognition, 34(2), 344–355.

- Schweiger, W. (1999). Medienglaubwürdigkeit – Nutzungserfahrung oder Medienimage? Eine Befragung zur Glaubwürdigkeit des World Wide Web im Vergleich mit anderen Medien. In P. Rössler, & W. Wirth (Eds.), Glaubwürdigkeit im Internet: Fragestellungen, Modelle, empirische Befunde (pp. 89–110). München: Reinhard Fischer.

- Slater, M. D. (2003). A note on presence terminology. Presence Connect, 3(3), 1–5.

- Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Communication Theory, 12(2), 173–191.

- Sojka, J. Z., & Giese, J. L. (2006). Communicating through pictures and words: Understanding the role of affect and cognition in processing visual and verbal information. Psychology and Marketing, 23(12), 995–1014.

- Steuer, J. (1992). Defining virtual reality: Dimensions determining telepresence. Journal of Communication, 42(4), 73–93.

- Sundar, S. S. (2008). The MAIN model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In M. Metzger & A. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital media, youth, and credibility (pp. 73–100). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Sundar, S. S., Bellur, S., Oh, J., Xu, Q., & Jia, H. (2014). User experience of on-screen interaction techniques: An experimental investigation of clicking, sliding, zooming, hovering, dragging, and flipping. Human–Computer Interaction, 29(2), 109–152.

- Sundar, S. S., Jia, H., Waddell, T. F., & Huang, Y. (2015). Toward a theory of interactive media effects (TIME). In S. S. Sundar (Ed.), The handbook of the psychology of communication technology (pp. 47–86). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sundar, S. S., Kang, J., & Oprean, D. (2017). Being there in the midst of the story: How immersive journalism affects our perceptions and cognitions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(11), 672–682.

- Taddicken, M. (2013). Climate change from the user’s perspective. Journal of Media Psychology, 25, 39–52.

- Tran, H. L. (2015). More or less? Multimedia effects on perceptions of news websites. Electronic News, 9(1), 51–67.

- Van Damme, K., All, A., De Marez, L., & Van Leuven, S. (2018). 360° video journalism: Experimental study on the effect of immersion on news experience and distant suffering. Journalism Studies. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2018.1561208

- Wang, S., Corner, A., Chapman, D., & Markowitz, E. (2018). Public engagement with climate imagery in a changing digital landscape. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(2), e509–e527.

- Wathen, C. N., & Burkell, J. (2002). Believe it or not: Factors influencing credibility on the Web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(2), 134–144.

- Xu, Q., & Sundar, S. S. (2016). Interactivity and memory: Information processing of interactive versus non-interactive content. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 620–629.

Appendices

Appendix A. Screenshots of the stimulus image