Abstract

In 2001, HBO and the BBC released Conspiracy, a critically acclaimed dramatization of the Wannsee Conference, where Nazi officials discussed coordinating the Final Solution in January 1942. Written by Loring Mandel, Conspiracy is noted for its strict adherence to the historical record as well as its chamber play atmosphere. However, HBO originally planned Conspiracy as the first half of a two-part feature. Its unproduced second half, Complicity, would have depicted Allied indifference to the Holocaust, the plight of Jewish refugees, and the rise of Adolf Eichmann. This article discusses the origins, pre-production history, and cancellation of Complicity. Grounded in archival documents – screenplay drafts, meeting minutes, research files, as well as oral history interviews, this presentation will trace Complicity’s beginnings as a story about Jewish efforts to inform the UK and US governments about the Holocaust and its transition to a dramatization of the April 1943 Bermuda Conference, which is most notable for its failure to meaningfully address the 1940s refugee crisis. Complicity is a fascinating example of ‘shadow quality TV’.

1. Complicity: an unmade holocaust film

In 2001, Conspiracy, a critically acclaimed dramatization of the Wannsee Conference, where Nazi officials discussed coordinating the Final Solution in January 1942, premiered on premium cable broadcaster HBO in the US and on public television (the BBC) in the UK.Footnote1 Directed by Frank Pierson and written by Loring Mandel, Conspiracy is noted for its strict adherence to the historical record, precise, chilling dialogue, and its chamber play atmosphere. HBO originally planned Conspiracy as the first half of a two-part feature. Its unproduced second half, Complicity, would have depicted Allied indifference to the Holocaust, the plight of Jewish refugees, and the rise of Adolf Eichmann. In an interview for James Andrew Miller’s recent oral history of HBO, Tinderbox: HBO’s Ruthless Pursuit of New Frontiers, then-HBO CEO Jeff Bewkes briefly discussed the decision to cancel Complicity:

Given the wider considerations of the war, I questioned whether it was fair to charge the United States with conscious complicity in the Holocaust. The answer I got was that we’d get a lot of attention, to which I said, ‘No shit. Let’s talk it over with the creative team.’ I had to respond with, ‘No, in a war for survival of the country, the duty of the American president is to save ‘our’ people, the American people, before saving refugees in Europe. Look at the list the Nazis drew up in Wannsee: they were planning to kill thirteen million people and we stopped them halfway by winning the war.’ Dead silence in the room. I’m sitting there thinking, Great, here’s a career ender for me. The goy who took over from Michael Fuchs shuts down a Holocaust justice movie, clearly an anti-Semite. I’ll have to leave the industry by Monday. And then an authoritative voice comes from the corner. ‘He’s right. We’re better off not making this argument. Ben-Gurion said as much in 1948.’ Brian Wapping, professor of history at Oxford. Thank God. (Miller, Citation2021: 376–77)

Intended as an adaptation of David S. Wyman’s controversial 1984 book The Abandonment of the Jews, Complicity also sought to adapt the biographies of key individuals discussed in Wyman’s book, most notably Gerhart M. Riegner and John Pehle. Grounded in archival documents – screenplay drafts, HBO meeting minutes, research files, as well as oral history interviews, this article traces Complicity’s beginnings as a story about Jewish efforts to inform the UK and US governments about the Holocaust and its transition to a dramatization of the April 1943 Bermuda Conference, which is most notable for its failure to meaningfully address the 1940s refugee crisis. Over two decades later, HBO’s reasons for dropping the project remain murky. Complicity is a fascinating example of shadow ‘quality TV.’Footnote3

HBO NYC Productions producer Colin Callender approached Conspiracy’s screenwriter Loring Mandel regarding another project he was producing on the Holocaust. The director Frank Pierson, best known for writing Dog Day Afternoon (1975) and Cool Hand Luke (1967), was already on board to direct the Complicity project and had offered comments on a script earlier in 1996. (Pierson, Citation1996) This drama was to be about Allied indifference to the Holocaust and would focus on Gerhart Riegner, a German-Jewish refugee living in Switzerland and secretary of the World Jewish Congress. Riegner is best known for his 1942 attempts to notify the American and British governments about the Holocaust after receiving word about the Germans using gas to murder Jews by the thousand. Callender already had a script by the British playwright David Edgar but was unsatisfied. He would quickly turn Edgar’s script over to Mandel and the project would evolve into a double feature or three-hour epic: ‘[Callender] felt that this was big enough that he could do the two scripts in consecutive Saturday nights on HBO’ (Mandel, 2019: 50:00–55:24).

Mandel’s second draft of Conspiracy contained revisions stemming from the film’s attachment to the Complicity project. This new material would have begun with an animation of a plane flying over a map of Europe, intercut with stock footage of anti-Jewish persecution and wartime combat footage. Narration would survey each step towards war and Germany’s radicalizing anti-Jewish policy while the map showed the Nazi march through Europe. This stock footage was also to be intercut with shots of Eichmann beginning to work as ‘an expert on the ‘Jewish Question’’ in Vienna (Mandel, Citation1996: 1–3). This script is the earliest evidence of the combined Conspiracy/Complicity project, which sets out to tell the story of the Holocaust with Eichmann as its antagonist and Gerhart Riegner as its protagonist. The new introduction, after showing shots of Eichmann going about his work, cuts to Gerhart Riegner in Geneva: ‘The office is crowded with Jews seeking visas. These are mostly well-dressed men and women. Gerhart RIEGNER, 28, is furiously writing and talking at the same time as applicants shout and wave for his attention’ (Mandel, Citation1996: 3). The stock footage and map animations continue into June 1941, introducing Anthony Eden and Winston Churchill as the narrator states that ‘[s]ecret German dispatches describing the massacres were known at once to the British as a result of the ingenuity of their cryptographers, who had broken the German codes. All that summer, the Prime Minister had access to the Nazis’ own reports of the Jews, Russians and Poles they murdered’ (Mandel, Citation1996: 4–5). John Pehle, U.S. Treasury Department lawyer and later director of the War Refugee Board, also appears in this section. The script describes him as someone who ‘routinely arranged licenses to permit American citizens to spend dollars in friendly or foreign countries,’ then shows stock footage of the Pearl Harbor attack and notes that this process continued even after the Axis declaration of war. Finally, the new introduction mentions German setbacks on the Eastern Front, then transitions seamlessly into the early Conspiracy script discussed above (Mandel, Citation1996: 4–5). The introduction, in comparison with the remainder of the script, appears conventional due to its inclusion of stock footage and its omniscient narrator, who leads the audience around the world and introduces key characters. It is maximalist where earlier drafts (and the final version) of Conspiracy were minimalist.

In late 1996, after delivering his draft of Conspiracy, HBO NYC Productions asked Mandel to rewrite an already-existing script for Complicity. For most of its production history, Conspiracy was the first half of the story told in Complicity – the majority of pre-production documents from this period address both films. For the next two years, the production team would grapple over how to best depict the Allied response to the Holocaust – until the project’s cancellation and subsequent revival. When a film project is cancelled, the only way for historians to investigate it is through the written record. Because we are left with scripts, meeting minutes, and sources, we essentially only have fragments of an unfinished film. No complete work survives. Some scholars refer to these fragments as ‘shadow cinema’ (Fenwick, et al. Citation2020). When Colin Callender turned over the Complicity script to Mandel, the playwright David Edgar had already delivered two drafts of the screenplay to HBO. Director Frank Pierson had by then provided extensive comments on this screenplay. Edgar, a left-wing journalist from the UK, had built his reputation on his plays about right-wing ideology, such as Destiny (1979), a drama about the rise of the National Front in Britain, or Maydays (1983). His most famous work was the Charles Dickens adaptation The Life and Death of Nicholas Nickleby (1980). Compared to Conspiracy, which tightly focuses on a single historical event and location, Edgar’s Complicity script is much broader in scope. It tells the story of Gerhart Riegner’s efforts to inform the Allies about the Holocaust, Eichmann’s activities between Wannsee and the war’s end, the 1943 Bermuda Conference, infighting within the Roosevelt administration, tensions within the American Jewish community between radical Zionism and caution, a Jewish woman hiding in France, and the decision not to bomb Auschwitz (Edgar, Citationundated). Eichmann is Edgar’s antagonist, Riegner is its protagonist, something Mandel retained in his first draft of Conspiracy/Complicity but would later abandon. Edgar’s script is particularly adept in depicting how Riegner’s telegram about the Holocaust made its way through Allied bureaucratic channels (Edgar, Citationundated: 33–35). The main storylines later seen in Mandel’s version of Complicity are already present in Edgar’s script, though there are some major differences. For example, there is a will-they-won’t-they romance between Riegner and his secretary Myra, as well as a story about Riegner’s cousin Lotte’s capture in France and deportation to Auschwitz. The Bermuda Conference features, and Edgar juxtaposes it with the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, which occurred at the same time. In one powerful scene, Riegner, despondent about the Allied failure to rescue Jews or bomb Auschwitz – and directly after a refugee accuses him of doing nothing to help victims – destroys his US immigration visa application, resolving to remain in Geneva and continue helping refugees (Edgar, Citationundated: 156). In this script, Riegner’s story ends with him ‘look[ing] at the portraits of Roosevelt and Churchill. Then he goes to look out of the windows, at the mountains. His eyes are filled with tears.’ (Edgar, Citationundated: 158). The script ends in April 1945, with Eichmann providing Red Cross officials with a tour of Theresienstadt. Here, he utters his infamous statement which has been reprinted countless times; that he ‘would gladly, myself, jump into the pit, knowing that in the pit were five million enemies of the state.’ His glance then meets that of Riegner’s cousin, Lotte, and the story ends abruptly (Edgar, Citationundated: 159). David Edgar also provided a summary which included footnotes expanding on some of his ideas for the film. One, commenting on a scene depicting Eichmann noted that ‘I am putting in every possible moment of contrasting allied [sic] prevarication with Axis action’ (Edgar, Citation1996: 7). Contrasted with Mandel’s drafts, Edgar’s script differs in tone from Mandel’s, which contains more surgically precise dialogue like that seen in Conspiracy.

2. Loring Mandel takes over script

After HBO put Mandel in charge of writing Complicity, David Edgar provided him with information on the source material he had used for his script, as well as his notes which were contained on a floppy disk. Additionally, Edgar acknowledged that he had ‘piles of copies’ from David S. Wyman’s published primary source collections on America and the Holocaust, which provided the bulk of source material for his groundbreaking 1984 book The Abandonment of the Jews, the single most important secondary source for all versions of the Complicity script (Wyman, Citation1989, Edgar, Citation1997). Mandel would later go so far as to describe Complicity as a ‘cable adaptation’ of Wyman’s book (Mandel, Citation1997a). Mandel’s first draft, which contains sixty-three endnotes, cites Wyman a total of twenty-seven times (Mandel, Citation1997b: i–iv).

In June 1997, Mandel delivered his first version of the Complicity screenplay to HBO.Footnote4 His first draft is similar to Edgar’s version – it follows the basic plotline, but some subplots, such as the one with Riegner’s cousin Lotte, are abandoned in favour of a more detailed depiction of the Roosevelt administration and the Bermuda Conference. The script still follows Eichmann and dramatizes several events in the history of Auschwitz: the Vrba escape and report, the failure to bomb the camp, and the Sonderkommando uprising of 7 October 1944, later dramatized in the films The Grey Zone (2001) and Son of Saul (2015) (Mandel, Citation1997b). Although the plotlines are tightened, the script still retains Riegner as its tragic hero and Eichmann as its antagonist. In comparison to Conspiracy, it is quickly apparent that the early Complicity scripts depict enough events for several movies, let alone a 90-minute cable television drama – an issue with the script which would prove difficult for both budgetary and storytelling reasons.

Loring Mandel’s script directly draws a thematic parallel between the Wannsee and Bermuda Conferences:

INT. BANQUET ROOM, THE HORIZONS – MORNING

In this room, refurnished as a Conference Room, the American and British delegations sit around a highly-polished mahogany table, the Technical Experts (their briefcases and heavy research binders at hand) seated behind the major participants: Dodds, Bloom, Lucas and Reams; Law, Peake and Hall. Dodds actually has a gavel. There are pads and pencils, water pitchers and glasses, cigar and cigarette humidors. Reams has a heavy folder of papers, and will be taking notes. NOTE: The table, the room, the arrangement should all recall the Wannsee Conference as much as possible. (Mandel, Citation1997b: 52)

At one point in the script, Riegner and his colleagues discuss the Wannsee Conference and who attended it – highly unlikely considering the conference remained secret until Allied investigators discovered Martin Luther’s copy of the Wannsee protocol. They discuss the protocol as a ‘plan’ to exterminate all of Europe’s Jews; a fictionalized turn of events similar to War and Remembrance’s treatment of the protocol (Mandel, Citation1997b: 13–14). Unlike Edgar’s script, Mandel’s first draft of Complicity relies heavily on cinematic devices. The first of these is Riegner’s voiceover narration, which the filmmakers would insist upon until very late in the script’s development. For example, Riegner’s narration pops up at the beginning of the film as Heydrich leaves the Wannsee Villa, stating ‘this man here is Reinhard Heydrich. He’s leaving a mansion in Wannsee, near Berlin, where he’s just taken charge of Hitler’s Final Solution for the Jews’ (Mandel, Citation1997b: 1). After Heydrich is attacked in Prague, Riegner’s voiceover returns: ‘The good news: ten days later, Heydrich was dead of infection. The bad news followed’ (Mandel, Citation1997b: 5). Riegner’s voiceover is present throughout the script, even breaking the fourth wall and having the modern-day (late 1990s) Riegner directly address the audience (Mandel, Citation1997b: 11). At the end of the script, the elderly Riegner states ‘I won’t forget. (long pause) It’s all … the saddest story ever told,’ then stares at the audience as the screen fades to black (Mandel, Citation1997b: 120). When contrasted with Conspiracy, the Complicity script’s early reliance on narration seems overwrought and detracts from the minimalist aesthetic and the avoidance of exposition established in Mandel’s first draft of Conspiracy, which are some of that film’s most striking aspects.

Other cinematic devices appear misguided in retrospect. For example, Mandel included a proposal for a running onscreen counter of the number of murdered Jews, which would rise at different rates throughout the film:

And at the bottom of the screen a counter begins the fatal addition – similar to those signs that announce the acres of rain forest disappearing every minute, or deaths from cigarettes; it is running at medium fast rate now, later it will accelerate alarmingly, and towards the end of the movie when the total approaches six million, it will slow as there are fewer and fewer remaining Jews to kill. It will be more or less prominent – scene by scene – according to what is going on. Sometimes it may disappear entirely. We don’t want it to become distracting, but it will have a distinctive sound, counting the dead while the bureaucrats waffle and the anti-Semites stonewall, and the well-intentioned fail to act. (Mandel, Citation1997b: 18)

Comments on Mandel’s early drafts of Complicity (he would deliver his second at the end of July 1997 and his third that September) took priority over work on Conspiracy, which largely remained the same except for sections connecting it to its companion film. The producer Steven Haft commented on the script, providing a series of questions and suggestions. One comment argued that the script did not portray the British storylines as effectively as the American ones, and that because the BBC was co-producing the film, this area required improvement. He also questioned the script’s characterization of Roosevelt. His most emphatic suggestion was about Riegner’s narration, which he felt robbed the audience of suspense: ‘Overall, I do believe [the script] needs more tension. It also needs to reflect the passions of the period as much as possible. I do believe the narration, as rendered, hurts us on all these counts’ (Haft, Citation1997: 1–3). Mandel addressed Haft’s feedback in a letter to Frank Pierson, agreeing with some of it but rejecting Haft’s main suggestion about the narration, calling it ‘naive’ because ‘the reality of [the Holocaust] is too ingrained to be left in doubt; there will be no suspense on that question, no matter how the narration is framed’ (Mandel, Citation1997c: 1). Mandel argued instead that ‘the suspense in Complicity is about [w]hether anything is done and [h]ow incredibly obtuse (or worse) the Allies were.’ (Mandel, Citation1997c: 1). Mandel also pointed out that HBO needed to secure the rights to Gerhart Riegner’s story, as Riegner was still living at the time: ‘I have nothing whatever to base Riegner’s dialogue and narration upon, other than the mostly factual basis of what he’s reporting. The attitudes ascribed to him have been given to him as if he were a fictional character … Rights to his story should be negotiated before HBO gets into an even bigger money-hole on the project’ (Mandel, Citation1997c: 1).

The British journalist Alasdair Palmer, who HBO had brought on board as a consultant and researcher, also provided comments on Complicity towards the end of 1997. Palmer’s early comments praised Conspiracy but identified several problems with the Complicity script, which would eventually prove fatal. First off, he stated that the script was ‘much, much, much too ambitious in its scope’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 1). Concurring with Pierson’s comments on narration, he argued that most audience members already knew the broad strokes of Second World War history and did not need a narration to bring them up to speed, arguing that to do so would make audiences ‘feel bored, and possibly insulted, at being told the obvious in such elementary terms’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 1). The second problem Palmer identified was even more problematic from a historiographical and moral sense. For him, the film’s contrast between Riegner and Eichmann ‘seriously distorted and misrepresented’ the history of the Holocaust, because it implied Eichmann being ‘more or less single-handedly responsible for the Holocaust: using him as the focus for all those scenes creates the impression that if only the allies had decided to assassinate him, they would have stopped it all’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 2). Palmer rightly noted that this portrayal was ‘a serious distortion of the truth’ because it ignored that ‘[t]here were thousands of Germans (and Austrians) like Eichmann, all equally fanatical, and all equally willing … [a]ssassinating Eichmann would have had the same effect on the pace of the Holocaust as assassinating Heydrich: zero’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 2). He also argued that ‘the Holocaust was the result of a system, not a single evil genius,’ and that the film’s current portrayal of Eichmann portrayed him as one (Palmer, Citation1997: 2).

Palmer additionally noted that the script, which was already guilty of ‘distorting the reality, and over-loading the drama with a recitation of facts,’ also ‘suggests that the movie is setting up a straight moral parallel between Eichmann and US bureaucrats … But there is no parallel here. Failing to stop the Germans from gassing millions of Jewish women and children is not the same as actually ordering it yourself’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 2). Instead, he suggested that the movie should refocus, noting that had Allied bureaucrats ‘acted on the Riegner plan, and accepted Romania’s offer to sell 70,000 Jews,’ they would have acted as ‘a kind of inverse of Oskar Schindler’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 3–4). Palmer argued that ‘the main stories get swamped, lost in a blizzard of facts and narration,’ and that Riegner’s omniscient narration ‘diminishes alot [sic] of the drama’ because ‘[Riegner’s] gradual discovery of the true nature and extent of the Holocaust, and of the failure of the allies to do anything about it, ought to be highly tense and dramatic’ (Palmer, Citation1997: 4). Palmer suggested improving the script by focusing tightly on Riegner’s telegram and the Allied response to it, as well as the abovementioned proposal to ransom Romanian Jews (Palmer, Citation1997: 4–5). Later versions of the Complicity script would focus more strongly on Riegner and shorten the Eichmann storyline. In his first round of feedback, Alasdair Palmer identified the salient problems with Complicity which would plague it until Mandel decided to take a completely different tack by focusing solely on the Allied governments, using the Bermuda Conference as a centrepiece. Before Mandel made this change, the script would remain too bloated, too ambitious, too expensive, and too conventional for HBO to commit to it.

The historian Michael Berenbaum, perhaps best known for his early tenure at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C. as director of its research institute, served as a historical consultant for the production. When he first joined the team, he was the President and CEO of Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah Foundation, which he would leave by 1999 (USC Shoah Foundation, 1996). In February 1998, while he was still working for the Foundation, Berenbaum delivered his initial comments on the Conspiracy and Complicity scripts in a seven-page fax to executive producer Frank Doelger. He praised Complicity but noted that ‘[t]here may be too many characters and too little context’ (Berenbaum, Citation1998a: 7). Most importantly, Berenbaum identified one of the central weaknesses of the combined project at that stage of writing: ‘the linkage between the two part[s] of the script is historically flawed. The Allies did not know of the Wannsee Conference. It was not known even at Nuremberg and certainly not by Riegner, whose famous telegram of August 1942 speaks of a ‘plan under consideration and the Fuhrer’s[sic] headquarters’ and not an operational decision’ (Berenbaum, Citation1998a: 1). Berenbaum ended this fax by expressing his wishes to meet with Loring Mandel and the production team, praising their efforts but firmly stating that the screenplays needed improvement in certain areas: ‘The topic is fascinating. The program should be proximate to the Event it narrates’ (Berenbaum, Citation1998a: 7). The writer David Edgar, who had penned the first version of Complicity, also commented on the scripts that February (Edgar, Citation1998: 1).

After Edgar and Berenbaum commented on the scripts, Mandel delivered a fourth draft at the end of March 1998. In this stage of pre-production, Conspiracy: The Meeting at Wannsee was written to begin with Gerhart Riegner introducing the audience to the events about to unfold at Wannsee (Mandel, Citation1998: 1–4). Complicity was now titled Complicity: The Meeting at Bermuda and was more tightly focused than earlier drafts, which leaned more heavily on David Edgar’s script and covered a much wider range of events and locations (Mandel, Citation1998). A list of Complicity scenes for a proposed May 2000 shoot, dated 6 July 1998, shows that the team had already vastly trimmed down the project’s ambitious scale. It includes a list of deleted scenes such as Heydrich’s assassination, which was still included in script drafts as late as the spring of that year (HBO NYC Productions, Citation1996: 1–10).

In a script preface from 28 April 1998, Frank Pierson outlined his vision for the two films. This vision was more refined and clearer than Pierson’s earlier film ‘thesis statements’ and was clearly informed by several years of input from HBO officials, as well as the recent addition of Michael Berenbaum to the production team. Pierson’s preface strayed from the historical record and emphasized dramatic parallels between the Wannsee Conference and the Bermuda Conference, arguing that after the contents of Gerhart Riegner’s telegram got out ‘President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill finally ordered that a meeting of the Allies be held – a meeting in answer to the meeting at Wannsee, if you will – to determine what the world could do to halt the holocaust [sic]’ (Pierson, Citation1998a: 3–4). Pierson described Complicity as the story of the Bermuda Conference, arguing that it too ‘had been systematically planned by the men who arranged it … to do nothing’ (Pierson, Citation1998a: 4). The preface, which contains detailed descriptions of the characters in both pieces, as well as a bibliography, also includes a section titled ‘historical accuracy.’ Complicity was based on the minutes of the US and British delegations, but ‘in social situations and the dialogue of the newspaper reports we have had to invent, but in words attributed to individuals who were actually there we have them express the same positions they took on the record’ (Pierson, Citation1998a: 8). Here, Pierson devoted more attention to Breckinridge Long, arguably the villain of Complicity, stating that ‘Long’s statements and positions in meetings … are taken from his writings, his memoirs, and official documents’ (Pierson, Citation1998a: 8).

In Michael Berenbaum’s response, he noted problematic aspects of Complicity’s portrayal of Riegner, noting that the ‘plan’ mentioned in Riegner’s August 1942 telegram ‘was implemented in January [1942] … the drama is there. We don’t have to overstate the case. Perhaps Riegner can reflect on the gap between what he now [retrospectively] knows actually happened and what information he had at the time. Unless we specify this gap all the defenders of FDR will come out of the closet and attack this piece as unfair’ (Berenbaum, Citation1998b: 1). Berenbaum also stated that the screenwriters ‘must juxtapose’ the Bermuda Conference with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which occurred simultaneously. He also argued for the removal of Benjamin Netanyahu, father of the more famous Israeli Prime Minister of the same name and head of the New Zionist Organization of America during the war, from the script, noting that ‘Netanyahu was even less than a bit player. He was of no significance and the connection to Bibi would lead to misunderstandings’ (Berenbaum, Citation1998b: 3). Although Berenbaum was nominally the production’s historical advisor, he mostly commented on drafts and did not have the time to visit archives, photocopy source material, and conduct what historian John Lewis Gaddis has aptly referred to as the ‘ductwork’ of research (Gaddis, Citation2002: xi). For that, HBO would need to hire their own full-time researcher.

Based on comments at this point and the available archival material, the bulk of the production team’s efforts by mid-1998 were focused on Complicity. Conspiracy had a screenplay that was in need of more detailed historical input and fact-checking, but the broad strokes were there. Complicity was much more difficult. At the behest of Frank Doelger, HBO hired Andrea Axelrod, a journalist and freelance writer with a background in drama, as a full-time researcher and fact checker. She had attended Williams College and remained friends with Doelger, her former classmate (Axelrod, 2018: 21:51–25:27). Axelrod contended that ‘my charge was to document every line, so that Holocaust deniers couldn’t come after us’ (Axelrod, 2018: 00:53–03:46). The most likely explanation for this claim about combating Holocaust denial has more to do with the historical context than any concrete wishes on the part of the production team. The verdict in the Holocaust denier David Irving’s libel case against the historian Deborah Lipstadt was reached in April 2000. This trial was extensively covered by the press and certainly would have been of interest to people working on a Holocaust film at the time (Guttenplan, Citation2001, Evans, Citation2002, van Pelt, Citation2002, Lipstadt, Citation2016).

The earliest known document mentioning Axelrod concerns primary source documents related to the Bermuda Conference, which she had requested from the US National Archives. This letter is dated July 1998, so she likely began several months earlier (NARA, Citation1998). The Loring Mandel archive contains several boxes of photocopied research material gathered by Axelrod at various archives throughout the US, the vast majority pertaining to Complicity and the Bermuda Conference.Footnote6 Because most of her early work was devoted to finding and gathering source material, very little correspondence involving Axelrod has survived from this period. She would later go on to provide the bulk of fact-checking support once filming was imminent.

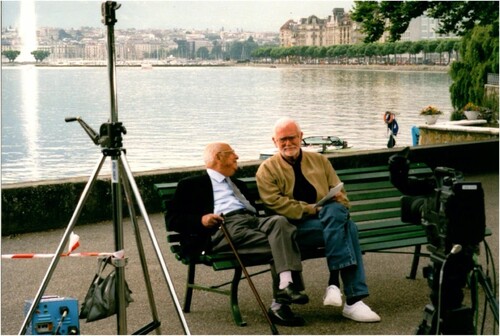

By 1998, both scripts focused on Gerhart Riegner as narrator, with Complicity directly depicting his efforts to inform the British and American governments. Producer Frank Doelger and journalist Alasdair Palmer had previously travelled to Geneva and interviewed Riegner (Doelger 2020: 18:00–18:35). One surviving fifty-three-page transcript of a subsequent interview with Riegner conducted by Frank Pierson, Loring Mandel, and Frank Doelger can be found in the Loring Mandel Collection. In this interview, conducted in June 1998, Pierson mentions meeting Riegner three years prior and discusses Loring’s script up to that point. The interview also mentions Peter Zinner having met Riegner the day before (Riegner, Citation1998). Pierson also filmed an interview with Riegner, which would have likely been used in either an accompanying documentary or directly spliced into Complicity (Mandel, 2019: 41:23–55:24). The interview also mentions possibly filming on location at The Horizons in Bermuda, the resort where the Bermuda Conference took place (Riegner, Citation1998: 36). These interviews are not contained in the Mandel collection, but photographs of Pierson and Riegner at Lake Geneva surrounded by cameras and lighting equipment have survived. The multiple trips to Switzerland, as well as the costs for filming an interview, would not have been cheap and illustrate the degree of HBO’s financial commitment to the project ( and ).

FIGURE 1 Gerhart Riegner and Frank Pierson on the shore of Lake Geneva, Summer 1998.Footnote8

FIGURE 2 Filming Pierson and Riegner at Lake Geneva, Summer 1998.Footnote9

3. Cancellation and revival

Little archival documentation exists surrounding HBO’s cancellation of Conspiracy and Complicity in the summer of 1998, though Bewkes’ account likely provides some clues. One document written by Frank Doelger during the same year mentions that ‘budgets are under great scrutiny at HBO,’ asking Mandel and Pierson to trim down montages in Complicity, which would have simply cost too much to shoot (Doelger, Citation1998). In an interview, Loring Mandel credited producer Colin Callender with reviving the project after its 1998 cancellation. (Mandel, 2019: 55:24–57:42). The most detailed – if biased – account of HBO’s 1998 passing on the project can be found in a fax Frank Pierson sent (alongside Mandel’s screenplay and Pierson’s preface) to the liberal activist and lawyer Stanley Sheinbaum at the end of September 1998. In this letter, Pierson expressed deep bitterness and anger about the fate of what had been his passion project, stating that ‘I am devastated by this, but more than anything I am saddened and angered by the reasons for it happening. The historical record needs to be read; it is not enough for a few scholars to know and understand – if history is not recreated for each generation it might as well be forgotten and its lessons left unlearned’ (Pierson, Citation1998b: 2). Regarding HBO’s decision to pass on the project, Pierson alleged that ‘HBO has lost its nerve’ and that the executives Bob Cooper and Michael Fuchs, whom he had originally pitched Conspiracy to, ‘[were] a different management team’ than the new HBO executives (presumably Jeffrey Bewkes and Chris Albrecht) who had just passed on the project and that Colin Callender ‘had the brilliant idea of coupling the two productions’ (Pierson, Citation1998b: 1). In this document, where Pierson reminisced about the project and looked at it from what was then a retrospective vantage point – he could not have known that HBO would pick it back up a year and a half later – the director noted the difficulties faced by the production team:

… during this period of writing and rewriting, a new regime at HBO was grappling with formulating their own production philosophy, but also growing more and more uncomfortable with the idea of depicting our wartime leaders as in any way complicit. I believe they are particularly disturbed by the portrayal of some of Roosevelt’s trusted officials (Breckinridge Long in the State Department, for one) as openly anti-Semitic, and of Roosevelt himself avoiding the issue because of feared political backlash. (Pierson, Citation1998b: 2)

I hope HBO is not losing its nerve and adventurousness that made it a vibrant and exciting place to work and – because of the excitement that conveyed – made it a commercial success as well. It was – perhaps may yet be – the last best place for a cinema of ideas to leaven the tsunami of commercial entertainment. (Pierson, Citation1998b: 3)

Against the background of American isolationism and anti-immigration bigotry there is the stark fact of anti-Semitism. Quotas and bars in education and employment. Foreign languages not taught in public schools – labor unions anti-immigrant. And the generation in their working years wanted to forget their foreign heritage. The Jews of Hollywood expunging all Jewishness from their films; what foreignness allowed was the cuteness of the Irish. (Pierson, Citation2001: 1)

Instead, Pierson suggested that Long’s attitudes were a product of systemic American flaws:

It was not one man, or even his department but a large sentiment of the public, that took the form of mass deportations of ‘enemy aliens’ in the twenties, by J. Edgar Hoover, and a steady deluge of denunciation of foreign influences and spies, communists, socialists, and Jews, in the press and on the radio, by Catholics on the one side and the Ku Klux Klan and Protestant churches on the other. (Pierson, Citation2001: 3)

I remember an argument with my first Father in Law, a blood and money member of what used to be called ‘old money,’ a third generation stock broker, member of all the most exclusive clubs, drove Fords and Plymouths, regarding Cadillacs as gangster cars, and a Rolls Royce as embarrassing pretension and an irresponsible waste of money. I was talking about the desirability of kids going to schools where they would meet members of all classes, as a desirable aspect of democratic society. ‘You mean take Negroes at ‘The Hill,’?’ he asked[.] The Hill is the name of the prep school to which we both had gone – I on scholarship. I said yes. He though[t] for a moment, and said ‘My God, I always thought the reason to go [to] a good school was so you wouldn’t have to meet them’. (Pierson, Citation2001: 3–4)

4. End of the complicity project

Pierson’s February 2001 script notes served as a road map for the final iterations of Mandel’s screenplay. It retains much of the dialogue found in earlier drafts but has a tighter focus. It focuses on Breckinridge Long and Henry Morgenthau as its two leads, with Long as the film’s antagonist. Riegner’s presence is greatly reduced, and the film limits itself to depicting his historical efforts. Riegner offers no commentary or narration as in previous versions of the script. He does however remain one of the screenplay’s moral centres. At the end of the film, in a postwar conversation with Paul C. Squire, the American consul in Switzerland he had dealt with during the war, Riegner says ‘I’m all admiration for you people. All I say is this: for you people, what was happening to the Jews was perhaps tragic, but it did not become unbearable. It did not become unbearable. Paul, it did not’ (Mandel, Citation2003: 109). That is the overarching message of Mandel’s script, in which he depicts the US State Department as filled with nativists and antisemites (a faction headed by Long) and the rest of the US government as slow to act, naïve, or indifferent. Roosevelt comes across as easily bored, worried about his reelection chances or the wider events of the war. He only agrees to form the War Refugee Board via executive order when Morgenthau forces his hand and gives him no other choice – up to that point, he defends Long from accusations of antisemitism and dishonesty, but snubs him by the end of the film, foreshadowing Long’s resignation. There are simply too many cuts back and forth between the Bermuda Conference and Washington – Conspiracy, for example, does not cut back and forth between the Wannsee Conference villa and Hitler’s headquarters. Instead, it sticks to one location.

In several interviews, Mandel claimed that HBO cancelled Complicity because of a fear of offending FDR’s descendants and admirers, most chiefly among them the attorney and diplomat William vanden Heuvel, then head of the Roosevelt Institute. Mandel also explicitly named then-HBO Executive Vice President Richard Plepler as the individual responsible for cancelling the project, alleging a family connection to the vanden Heuvels, which would have meant that Plepler had a vested interest in protecting FDR’s reputation (Mandel, 2018, 18:51-23:09). Mandel claimed that Colin Callender informed him that the network was moving away from historical films: ‘When Colin called me to tell me that they were not going to go forward with Complicity, he said that HBO had decided to concentrate on contemporary pieces rather than historical pieces. Which was pretty ludicrous’ (Mandel, 2019, 05:53-09:54). He also hedged, noting that he could not be sure ‘who pulled the plug,’ but that his feelings leaned towards Richard Plepler due to a conversation he had had with the executive:

[T]he impression I got from the conversation was that [Plepler] was very concerned about the picture [portrayal] of Roosevelt that appeared in the film Complicity. So what I said … was, is really imposition on my part because I have no real way of knowing whether he was the one who plugged the plug on it or someone else. But he was the only one who expressed an attitude toward me that gave me reason to think that he was probably the one. (Mandel, 2019: 05:53–09:54)

Surviving documentation in Loring Mandel’s papers proves scarce, but a February 2003 fax from Plepler regarding Complicity survives. In this fax, Plepler suggests that Mandel consult William vanden Heuvel, former diplomat and founder of the Roosevelt Institute, about the project: ‘I think he’d be a wonderful person for you to get in touch with, and I recommend that you do so’ (Plepler, Citation2003: 1). Plepler included a letter from vanden Heuvel with the fax. In this letter, written a week earlier, vanden Heuvel stated ‘For years I have lectured on various subjects relating to the Holocaust … I would greatly appreciate your bringing these efforts to the attention of those who are engaged in the film and would be pleased to meet with them for a general discussion relating to the subject.’ The letter also alludes to vanden Heuvel’s comments on Michael Beschloss’ The Conquerors, a history about the Roosevelt and Truman administrations and the war effort against Nazi Germany which sharply criticizes US immigration policy and failure to bomb Auschwitz (vanden Heuvel, Citation2003a: 1). While vanden Heuvel’s letter at first appears to be a generous offer of help, his mention of The Conquerors reveals his true feelings about Complicity. Vanden Heuvel negatively reviewed Beschloss’s book, arguing that he joined the ranks of a ‘discredited group’ of historians like David S. Wyman, claiming that it was unfair to accuse the United States of indifference or complicity when it came to the fate of European Jews (vanden Heuvel, Citation2003b). Plepler and vanden Heuvel were friendly (in this correspondence, they refer to each other on a first-name basis). Vanden Heuvel had a history of vociferously defending any allegation on indifference or antisemitism on the part of FDR’s administration. He had previously been part of a publicity campaign against the 1994 PBS American Experience documentary America and the Holocaust: Deceit and Indifference, which largely advances David S. Wyman’s thesis from The Abandonment of the Jews. Wyman appears at several points during the documentary (de Witt, Citation1994). By contacting Plelper about Complicity, vanden Heuvel was seeking to prevent another prominent television production from tarnishing Roosevelt’s legacy. In terms of historiographical camps, David S. Wyman can be considered the most mainstream anti-Roosevelt position, with William vanden Heuvel espousing the most pro-Roosevelt line. In his influential study The Holocaust and American Life, historian Peter Novick dismissed Wyman for a simplistic moral narrative, somewhat prefiguring Bewkes’ remarks quoted at this article’s beginning (Novick, Citation1999: 48). Recent scholarship, particularly Richard J. Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman’s judicious FDR and the Jews, manages to split the difference and move beyond the heated debates of the 1990s, arguing that ‘FDR was neither a hero of the Jews nor a bystander to the Nazis’ persecution and then annihilation of the Jews,’ and that when taking a longer view of American presidents, FDR did the most for Jews and victims of genocide than both his predecessors and successors – it is important to also mention that the authors do not let the US State Department off the hook, correctly depicting their obstruction of immigration during this period (Breitman and Lichtman, Citation2013: 315–29). Plepler’s correspondence with vanden Heuvel and suggestion that Loring Mandel bring him on board is no smoking gun, but it certainly points to a potential effort to steer the production away from its central thesis – it is hard to argue that Pierson and Mandel would have remained on board if vanden Heuvel’s need to protect FDR’s legacy was represented at production meetings and gained traction among HBO executives.

Frank Doelger discussed Complicity and Mandel’s bitterness towards HBO and Richard Plepler, denying Mandel’s allegations of some need on HBO’s part to protect FDR’s reputation, arguing instead that HBO had put too much effort into a project that had no future. Doelger even admitted that he had been the one to tell HBO to pass on the project:

[HBO] were very concerned about making sure the appraisal [of the US government’s actions] was fair. Also, there was so much information out there. We had lots of consultants, we read a lot of material, and there were certain things like that meeting which could be interpreted one way or another. But the record was pretty clear, we have Breckinridge Long’s memos, we had what Morgenthau was doing, you know. Actually, I would say that Loring [Mandel] may have been told that [the project had been canceled due to pressure from Plepler or vanden Heuvel], but he certainly wasn’t told it by me. But I just know that as the person trying to develop that project working with Loring, working with Frank [Pierson], that there was no way to tell a satisfying drama as a companion piece to Conspiracy at all. Based on the Bermuda Conference and based on this whole question of how this information got out, what was going on … .You probably could have done that story in 4 or 5 hours, but again it’s a story that would be better told as a documentary. I think I was the one who told HBO not to make it. I think I did. I remember telling them that. We had spent a lot of time and energy, and I was never convinced we were going to get there. So I think, I’m sure that I’m the one who informed everybody. (Doelger, 2020: 15:04–18:24)

In an interview, Michael Berenbaum noted other reasons HBO may have passed on Complicity: ‘I think [HBO] were scared of provoking the American government’ (2021: 22:09–23:33). Berenbaum argued that rather than a worry about provoking FDR’s promoters, HBO’s decision instead was simply a product of the larger post-9/11 political climate: ‘This is the period of time right after 9/11. So, I think it is less about Roosevelt more about the ethos of government at that time … a terrible time in which America felt itself under besiegement … also felt that there was a real enemy out to get us. And we were united in a very particular way behind George W. Bush. And that’s before he fucked it up’ (2021: 29:25–30:44). HBO’s feel-good FDR film Warm Springs is evidence of this climate. This is a time when Americans were looking for unity, not division – and that meant comforting stories about the past, not pieces overtly critical of one of America’s greatest liberal heroes and wartime presidents. In 2022, the pendulum swung the other way. The renowned documentarian Ken Burns, a filmmaker not disposed to radical politics, released the series The U.S. and the Holocaust on PBS. (Citation2022) While Burns’ series does not cover the Bermuda Conference, it argues that the United States was rife with antisemitism, including at the highest levels of power. Although Burns also made a fawning series about the Roosevelts as a political dynasty, FDR does not escape criticism in The U.S. and the Holocaust. The series constantly addresses the rescue question and, although not as damning as Mandel and Pierson would have liked Complicity to be, it comes close. Gerhart Riegner is a central figure in the series and upon viewing, one wonders what might have been. The United States depicted here has much more in common with that racist and antisemitic society described by Pierson and Mandel; it is a place with dark impulses epitomized by the Ku Klux Klan and Charles Lindbergh. Additionally, in Citation2023, Netflix released the dramatic miniseries Transatlantic, which recounts the efforts of the journalist and activist Varian Fry to rescue persecuted cultural figures like artists and academics from wartime Europe. The series condemns U.S. State Department antisemitism and antiimmigrant attitudes in ways quite similar to Wyman and Mandel. Burns’ documentary series and Netflix’s Transatlantic excels at depicting the contingency of U.S. politics in the 1930s and both the apathy and active bigotry at the heart of institutions like the U.S. State Department. By drawing attention to nativist and antisemitic attitudes at the heart of American political power, these two series are characteristic of a changed cultural mood following the election of Donald Trump in 2016. In contrast with the post-9/11 climate of unity and patriotism, these productions contain a critical, warning tone towards American culture and policy. The U.S. and the Holocaust and Transatlantic show that Complicity may have simply been ahead of its time. In his landmark study While America Watches: Televising the Holocaust, television historian Jeffrey Shandler argued that ‘the primacy of television and other mediations in [American] memory culture has situated Americans in the distinctive posture of watching – emotionally, ideologically, and intellectually engaged, yet at a physical, political, and cultural remove.’ (Shandler, Citation2001: 261). The unmade history of Complicity shows that filmmakers have continually attempted to overcome that remove.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicholas K Johnson

Nicholas K. Johnson is a senior lecturer at the University of Münster, Germany. His dissertation project focuses on the history of how the Wannsee Conference has been depicted German and American film and television since 1960. Holding an M.A. in Public History from Indiana University (2016), his research interests include the depiction of history in film, public history, and Holocaust studies. He is also the co-editor of Show: Don’t Tell: Education and Historical Representations on Stage and Screen in Germany and the USA (2020).

Notes

1 The research for this article originally stems from my dissertation, ‘The Wannsee Conference and Television Docudrama: Holocaust Education and Public History, 1960–2022,’ submitted to the University of Münster, Germany, in 2022.

2 All referenced primary sources are located in the Loring Mandel Collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research in Madison, Wisconsin unless otherwise noted.

3 By ‘Shadow Quality TV,’ I refer to the concepts ‘Shadow Cinema’ outlined by James Fenwick, David Eldridge, and Kieran Foster (Citation2020) and ‘Quality TV’, a term common among television critics and scholars largely writing about American cable drama post-The Sopranos (McCabe and Akass, Citation2007).

4 Note that Mandel consulted with Pierson and most likely Peter Zinner before delivering drafts to HBO, letting them provide feedback on ‘assembly drafts.’ See Loring Mandel, ‘Pt 1’ (handwritten on first page): untitled script of Complicity, ‘First Assembly Draft 5/22/97’, with notes, with handwritten emendations, 22 May 1997, in Box 3, Folder 1, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942–2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

5 FDR is how most Americans refer to and referred to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in order to distinguish himself from his relative, President Theodore Roosevelt, who often went by ‘TR.’

6 See Boxes 12 and 13, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942–2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

8 Photo of Trip to Geneva, Box 19, Folder 6, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942–2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

9 Photo of Trip to Geneva, Box 19, Folder 6, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942–2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

7 Hartman defines normative America as ‘‘a cluster of powerful conservative norms [which] set the parameters of American culture … Normative Americans prized hard work, personal responsibility, individual merit, delayed gratification, social mobility, and other values that middle-class whites recognized as their own.’

References

- Axelrod, A., 2019. Interviewed by Nicholas K. Johnson, 9 March, New York City.

- Berenbaum, M., 1998. Michael Berenbaum to Frank Doelger, Box 10, Folder 7, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Berenbaum, M., 2021. Interview by Nicholas K. Johnson, 13 April, Online.

- Beschloss, M.R., 2002. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the destruction of Hitler’s Germany, 1941–1945. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Breitman, R., and Lichtman, A.J., 2013. FDR and the Jews (1st edition). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press.

- Doelger, F., 1998. Frank Doelger to Frank Pierson and Loring Mandel, Box 10, Folder 7, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Doelger, F., 2020. Interviewed by Nicholas K. Johnson, 2 April, Online.

- Edgar, D., 1996. COMPLICITY – revised summary of 2nd draft August 1996, in Box 2, Folder 2, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Edgar, D., 1997. David Edgar to Loring Mandel, in Box 10, Folder 10, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Edgar, D., 1998. Conspiracy\complicity notes, in Box 10, Folder 10, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942–2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Edgar, D., Undated. Untitled script of complicity, in Box 1, Folder 9, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Evans, R.J., 2002. Lying about Hitler (Reprint edition). New York: Basic Books.

- Fenwick, J., Foster, K., and Eldridge, D. eds. 2020. Shadow cinema: The historical and production contexts of unmade films. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gaddis, J.L., 2002. The landscape of history: How historians map the past. Oxford: Oxford University Press. U.S.A.

- Gillette, F., and Koblin, J., 2022. It’s not TV: The spectacular rise, revolution, and future of HBO. New York: Viking.

- Guttenplan, D.D., 2001. The Holocaust on trial. New York: Norton.

- Haft, S., 1997. Fax from Steven Haft to Frank Pierson, in Box 11, Folder 1, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Hartman, A., 2019. A War for the Soul of America, Second Edition: A History of the Culture Wars. University of Chicago Press.

- HBO NYC Productions, 1996. Complicity, one-line schedules for a proposed May 2000 shoot, in Box 6, Folder 9, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Holson, L.M., 2012. There’s something about Richard. The New York Times, 21 Sep.

- Lipstadt, D.E., 2016. Denial: Holocaust history on trial (Media Tie In edition). New York, NY: Ecco.

- Mandel, L., 1996. Conspiracy: The Meeting at Wannsee, 2nd Draft, in Box 2, Folder 7, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Mandel, L., 1997a. Loring Mandel to Elon Steinberg, World Jewish Congress, in Box 11, Folder 2, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Mandel, L., 1997b. Complicity, written by Loring Mandel, First Draft, 6/7/97, in Box 3, Folder 4, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Mandel, L., 1997c. Loring Mandel to Frank Pierson, in Box 11, Folder 1, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Mandel, L., 1998. Conspiracy (The Meeting at Wannsee)’ (first page) ‘Complicity (The Meeting at Bermuda)’ (page 121): combined script, ‘Rev Fourth Draft 4/27/98,’ in Box 6, Folder 4, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Mandel, L., 2003. Complicity, First Rev Draft, in Box 10, Folder 4, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Mandel, L., 2018. Interviewed by Nicholas K. Johnson, 5 April, Online.

- Mandel, L. 2019. Interview by Nicholas K. Johnson, 2 March, Somers, New York.

- McCabe, J., and Akass, K. eds. 2007. Quality TV: contemporary American television and beyond. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Miller, J.A., 2021. Tinderbox: HBO’s ruthless pursuit of new frontiers. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

- National Archives and Records Administration, 1998. NARA to Andrea Axelrod, in Andrea Axelrod Private Archive, New York City, New York.

- Novick, P., 1999. The Holocaust in American life. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Palmer, A., 1997. Comments on conspiracy\complicity, in Box 11, Folder 3, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Pierson, F., 1996. Oneline Summary of Complicity Script, in Box 2, Folder 2, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Pierson, F., 1998a. Preface, in Box 6, Folder 7, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Pierson, F., 1998b. Frank Pierson to Stanley Sheinbaum, Box 11, Folder 4, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Pierson, F., 2001. Complicity: notes FEB 9 01 FRP, Box 11, Folder 4, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Plepler, R., 2003. Richard Plepler to Loring Mandel, Box 11, Folder 2, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Riegner, G., 1998. Transcript of interview with Gerhart Riegner, Geneva, Box 11, Folder 6, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Shandler, J., 2001. While America watches: televising the Holocaust. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Transatlantic, 2023. Netflix.

- The U.S. and the Holocaust, 2022. Florentine Films.

- USC Shoah Foundation, 1996. Berenbaum to Join Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation. https://sfi.usc.edu/news/1996/11/10333-dr-michael-berenbaum-join-survivors-shoah-visual-history-foundation

- vanden Heuvel, W.J., 2003a. William J. vanden Heuvel to Richard Plepler, in Box 11, Folder 2, Loring Mandel Papers, 1942-2006, M2006-124, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

- vanden Heuvel, W.J., 2003b. Comments on Michael Beschloss’ The Conquerors. Passport, 34 (1), 27–38.

- van Pelt, R. J., 2002. The case for Auschwitz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Witt, K. de, 1994. Tv film on Holocaust is criticized as unfair to Roosevelt. The New York Times, 6 Apr.

- Wouk, H., 1980. War and remembrance. Glasgow: Fontana.

- Wyman, D.S. ed. 1984. The abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941–1945. New York: Pantheon.

- Wyman, D.S. ed. 1989. America and the Holocaust: a thirteen-volume set documenting the editor’s book the abandonment of the Jews. New York: Garland Pub.