ABSTRACT

Food waste has serious economic and environmental repercussions, and there is growing policy attention to this issue in Canada. This study investigates how the material characteristics of wasted food influence its circulation and management in the City of Guelph, Ontario. Based on interviews with informants across the food value chain, we learned that there is a high reliance on systems and techniques to determine when food becomes waste (including cold chains, best before dates, and aesthetic standards). We document how these systems pervade the food chain and food recovery efforts, and also note attempts to disrupt their momentum. Our analysis emphasizes the relational agency of food waste: how social and cultural contexts interact with food’s vital materiality in the determination of when it becomes waste, the circumstances under which waste can become food again, and how organic matter can find a second life as a source of energy and nutrients.

Introduction

Food waste refers to food that is fit for human consumption, but has not been eaten for a number of reasons, including appearance standards, misunderstood best before dates, and oversupply (Stuart Citation2009, Gustavsson et al., Citation2011, Lipinski et al. Citation2013). The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that about one-third of food produced globally for human consumption (1.3 billion tonnes) was lost or wasted in 2011, at a cost of approximately $750 billion per year (FAO Citation2013). In Canada, it was previously estimated that almost 40% of food produced for human consumption was wasted, which was estimated to be equivalent to $31 billion in lost value (Gooch and Felfel Citation2014). The same consultant team recently amended this estimate: they report that of 58% of all food produced is lost or wasted in Canada, at a cost of $49 billion (Nikkel et al. Citation2019). In addition to economic losses, food waste is an environmental issue. More than half the water used in food production goes to waste, farmland is inefficiently used, and nutrients in the soil are lost – especially if food waste is not composted (Fehr et al. Citation2002). Food waste is also a contributor to climate change: the decomposition of organic matter in landfills creates methane, which is a powerful greenhouse gas (FAO Citation2013).

Significant amounts of food are lost all along the food value chain; in affluent countries, about 50% of food waste generation occurs between production and retail or food service (Parfitt et al. Citation2010, Gustavsson et al., Citation2011). However, most studies of food waste in affluent countries focus on the household scale in order to quantify this waste and understand the dynamics of household wasting behaviour. More research is needed on food waste across the food value chain (Mena et al. Citation2011, Halloran et al. Citation2014, Katajajuuri et al. Citation2014, Aschemann-Witzel et al. Citation2015, Göbel et al. Citation2015). The lack of data on food waste generation and the evolving nature of the statistics described above hint at the difficulties in coming to know this phenomenon: its materiality is often hidden, underestimated, and misunderstood. For these reasons, we have undertaken a qualitative study to learn about how actors across the food value system define, recognize, and manage what they consider to be food waste. Furthermore, very little food waste is recovered across the food value chain, and prevention initiatives are limited (Thyberg and Tonjes Citation2016). It is therefore important to investigate the reasons why food is wasted and to understand the barriers to preventing and recovering this waste. This study focuses on how the material characteristics of food impact its disposal, and how this materiality shapes the systems and behaviours that emerge around food waste management.

We discuss a case study of food waste generation, prevention, and diversion at the nodes of the food value chain outside of household consumption in Guelph, Ontario. Since food systems are localized and place-based, local context is an important factor in food waste studies (Evans et al. Citation2012, Eriksson et al. Citation2015, Parizeau et al. Citation2015).

Materiality and waste

‘Matter matters’ in socio-ecological systems because the materiality of objects and materials can influence social relations and practices (Bakker and Bridge Citation2006). Objects, therefore, have a form of agency, and the capacity to impact the people and things around them (Bosco Citation2006, Sayes Citation2014, Liboiron Citation2016). Bakker and Bridge (Citation2006) argue that the agency of non-humans is not inherent, but is rather an emergent property of the networked relations in which they are embedded. This relationality also explains how objects can ‘have politics and are entangled in struggles of power and meaning’ (Liboiron Citation2016, p. 90). The concept of agency further implies that relationality is not static, but that it can take multiple forms depending on the other actors and actants with which they are networked: as Bakker and Bridge (Citation2006, p. 12) note, ‘the meanings attached to things (and the identities and subjectivities produced through these attachments) are multivalent and fluid.’

In her catalogue of scholarly engagements with waste, Moore (Citation2012) identifies ‘waste as actant’ as an emerging social science paradigm. From this perspective, waste has agency to act upon society in sometimes unexpected ways. It exists in networks with human and non-human others, impacts the social and material aspects of the assemblages it is part of, and is constitutive of scale. The materiality of waste can, therefore, influence its governance, the systems of which it is a part, and the behaviours of actors who encounter it (see also Gille Citation2010). For example, Magnani (Citation2012) demonstrates that both human and non-human factors influence incinerator planning in Italy (Magnani Citation2012), and Corvellec and Hultman (Citation2012) argue that a shift in Swedish waste governance to recognize the recoverability of waste materials necessitated new household behaviours and infrastructure, and new logistics, services, and business models in the waste management sector. Carenzo and Good (Citation2016) describe how the stigma of trash is transferred to low-income informal recyclers in Buenos Aires who recover recyclable items from waste stream. This material association impacts their interpersonal relationships, explaining some of the conflict between informal recyclers and the middle-class residents of the areas where they work.

Another aspect of the socio-materiality of waste is its definitional relationality. While the material condition of waste items may contribute to their disposability (e.g. decomposing food), it is the multiple relational meanings ascribed to such materials that create the phenomenon of ‘waste.’ An object or material becomes waste by being designated as such within social and cultural contexts. For example, Gregson et al. (Citation2010) document the material properties of asbestos that emerge during ship breaking activities. This once-useful insulating material is now recognized as a hazard to human health, although it is not dangerous while it is still stable and contained. However, the demolition process reanimates asbestos as a noxious waste material requiring special handling. When ship-breaking crews unexpectedly find asbestos, it requires the reorganization of the people and processes involved, and is disruptive of the presumed financial logics of salvage economies. In another example of the relationality of waste, Hawkins (Citation2009, p. 194) points to the material multiplicity of the plastic water bottle, noting that its many properties may be diversely enrolled in different relational networks; for example, ‘the material realities of its environmental impacts are aggressively displaced or foregrounded in the interests of making or destroying markets.’

The un-becoming of waste is also indicative of its relationality. Gregson and Crang (Citation2010) argue that waste is transformed via ‘treatment technologies’ into a resource, and thus is no longer identified as ‘waste.’ Waste policies may act to divert waste from landfills through recycling and reuse activities, performing what Gregson and Crang (Citation2010, p. 1029) refer to as a ‘vanishing trick.’ Corvellec (Citation2016) also describes how the social framing of food waste treatment facilities as ‘sustainability objects’ creates a feedback loop whereby the practice of transforming food waste into biogas and biofertilizers is understood as sustainable because the treatment facilities have been defined and designated as sustainability objects. The practice of materially reclaiming food waste is therefore bound up with the relational definitions of certain technologies and processes as ‘sustainable.’

Another aspect of the relationality of waste is its tendency to interrupt the systems it is embedded within. Moore (Citation2012, p. 781) posits that the materiality of waste is inherently disruptive of sociospatial norms, ‘whether because of its inherent qualities (risk, hazard, filth), or because of its indeterminacy (as out of place, disorder, abject).’ For example, Cockerill et al. (Citation2017) argue that the materiality of nuclear waste creates a problem for nuclear societies that requires perpetual management, rather than allowing for a singular solution. Khoo and Rau (Citation2009) describe how the materiality of different kinds of hazardous waste problematizes narratives and imaginaries of North–South waste flows, can lead to contestation and protest, and may interrupt economic development models. In describing the diverse materiality and toxicities of plastics, Liboiron (Citation2016) describes how different types of plastic have distinctive properties and differing capacities for harm depending on the context of where they are found. The agencies of different kinds of plastics are therefore diverse in their disruptive tendencies.

As a potential waste material, food also demonstrates agency, relationality, and the potential for disruption of social practices and systems. Some material characteristics of food are distinctive from other types of waste. Food never exists in a static or stationary state; it is always in constant flux, and is prone to rotting in a relatively quick time frame. It is an organic material that is subject to internal processes of growth and ripening in production, through to the microbial processes of decay (Bennett Citation2007, Evans et al. Citation2012, Alexander et al. Citation2013, Waitt and Phillips Citation2016). While human actions and technological interventions may delay or mitigate rotting processes, its eventual decomposition is an inherent property of food, and so temporality is an important aspect of the relational materiality of wasted food. This materiality of food elicits a response from humans: we are motivated to store it or treat it to prevent its spoilage, and we want to dispose of it quickly once it has spoiled because we find it disgusting and possibly dangerous. Alexander et al. (Citation2013) describe how spoiling food is haunted by the ‘absent presence’ of microbial life that may or may not be present. The possibility of pathogens like salmonella or E. coli are signalled by best before dates and implied by risk culture. The mere threat of such contamination is enough to transform edible food into waste. Alexander et al. (Citation2013) also note that human abjection toward decomposing food is not universal, but is culturally influenced (for example, mouldy Roquefort cheese is considered a delicacy by some). Similarly, some studies have observed that people have a moral objection to the wastage of food, although this sentiment is not universally expressed (Graham-Rowe et al. Citation2014; Fraser and Parizeau Citation2018).

The food supply chain is a unique one, with complex logistics designed to address specific handling concerns for perishable materials (Göbel et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, Halloran et al. (Citation2014) note that integrating food waste into a circular economy is more complicated that other waste sectors because of how food is transformed after its use: it cannot be broken down into component parts for recycling, like a car, computer, or other consumer goods. Specific treatment systems are needed to recover energy and nutrients from wasted food.

In an overview of recent studies of food as a relational object (or ‘more-than-food’), Goodman (Citation2016, p. 262) notes that there is a focus on the vital materiality of the matter of food. He notes that the ‘shifting socio-material life of food’ extends to the indeterminacy of defining when food becomes waste, recognizing that this moment could occur across the life of food. As Coles and Hallett (Citation2012) demonstrate with respect to salmon heads and salmon, the transformation from food to waste is not a one-way process, and waste may become food again under certain circumstances. For example, the authors describe how salmon heads and ‘trash fish’ are usually discarded early in the value chain, but were used as decorations for a particular fish stall in a London market. They were destined for the bin at the end of the day until the authors negotiated to buy them for a low price in order to turn them into stock. The relational nature of food waste is evident in these moments of becoming and un-becoming. Waitt and Phillips (Citation2016) contend that food becomes waste through disposal-oriented practices and that this relationship with the disposer is more constitutive of waste than the material qualities of the food itself. Similarly, Hepp (Citation2016) argues that the transformation from food to waste is more of a discursive transition than a material one. Alexander et al. (Citation2013, p. 349, emphasis in original) emphasize that

contemporary food waste in the developed world is not just managed, but generated by socio-technical networks that include people, companion animals, fridges and freezers, sell-by and use-by dates, electricity, sinks, the kitchen bin, wheelie bins, food waste caddies, biodegradable plastic bags, waste collection vehicles, drains, sewers, and landfills.

Methods

While others have studied the material factors that influence the circulation and disposal of food within households (e.g. Evans Citation2011, Watson and Meah Citation2013, Wait and Phillips Citation2016), our study considers how the relational materiality of food waste impacts its treatment in earlier parts of the food value chain. We investigated food waste across the food value chain in Guelph, a mid-sized city in Southwestern Ontario with a population of approximately 130,000 people (Statistics Canada Citation2018). Guelph has a high waste diversion rate compared to other municipalities (City of Guelph Citation2017), and so this is a relatively waste-aware community.

For this study, Van Bemmel conducted 33 semi-structured interviews with actors across the local food value chain including the farmers/producers, distributors, retailers, food service providers, and key informants working in the emergency food provision and waste management sectors. Respondents were asked about the day-to-day operations of their organization, and particularly about the management and diversion of surplus food and food waste. Questions assessed the factors influencing current food waste management practices, including policies and regulations, relationships with other actors in food/waste sectors, and the character of the food waste that they generated. Respondents were also asked about any challenges that they faced in reducing or diverting their food waste.

Waste is often considered a private and sensitive subject (Mena et al. Citation2011, Marshak Citation2012, Bagherzadeh et al. Citation2014). Many potential respondents declined to participate in an interview, and similar challenges have been noted by other researchers interviewing organizations about their food waste (e.g. Gooch and Felfel Citation2014). Some participants agreed to an interview but were reluctant to speak about their waste management practices. Furthermore, the only producers who we successfully recruited to participate in this study were small-scale farmers. We worked to address these limitations by triangulating between data sources. For example, if a retailer was reluctant to discuss the food that they donated, an emergency food provider who received food from that retailer could provide more information about this type of donation.

Results and discussion

Assessing food spoilage: material and mediated processes

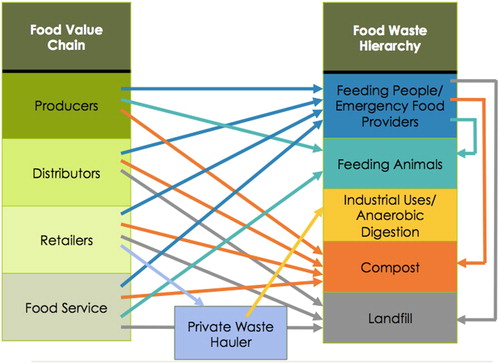

The interviews revealed that actors across the food value chain worked to divert surplus and waste food to various sources, as displayed in . However, the material properties of spoiling food (and the attendant systems created to manage food waste) constrained some of these pathways.

When interviewed about the management and potential diversion of their food waste, actors across the food value chain often referenced food’s quick material transformation to waste. The prevention of spoilage was therefore a high priority for diverse actors. The materiality of rotting food was associated with adverse outcomes, such as odours and pests:

They worry too much about uh, smells in the parking lot … cuz you’re gonna get – it can smell pretty ripe. (Retailer 2)

You can’t have stuff sitting there, rotting, which in essence, it really does, when it’s past a certain point … I mean, you can’t have these hanging around because … they’re going to attract pests. (Retailer 1)

Spoiled food was repeatedly referenced as a potential source of illness, and food management systems were described as a key means of avoiding the distribution of contaminated foods through sales or donation. Health scares like salmonella, listeria, and E. coli haunt the management of food and may hasten its designation as waste (Murdoch et al. Citation2000, Alexander et al. Citation2013, Milne, Citation2013). Temperature regimes and stock management (including the use of best before dates) are two key techniques that are employed across the food value chain to determine when food is still sellable/servable (see also Mena et al. Citation2011).

Refrigerating or freezing food requires a reliable cold chain throughout all stages of the supply chain (Institution of Mechanical Engineers Citation2013). There is detailed regulatory control over such products in Canada’s food safety system (Jol et al. Citation2007). Broken cold chains were found to be one of the root causes of food waste at the retail level (Mena et al. Citation2011, Uzea et al. Citation2013, Felfel and Rich Citation2015). Disrupted temperature regimes result in faster deterioration and increased potential for bacterial growth (Buzby et al. Citation2011). Some potentially donatable food is discarded because of temperature ‘abuse’ due to a broken cold chain (Buzby et al. Citation2011, Prakash et al. Citation2014, Eriksson et al. Citation2015), or because of lack of cold chain transportation or storage facilities. In particular, producers often do not have cold storage to store surplus harvest, and organizations receiving donations often have no place to properly store perishable items:

… we’ve had some offers for fresh produce, which we cannot accept - we don’t have any place to store anything fresh. (Emergency Food Provider 2)

We get all this food, and then we don’t really have spaces to store it because the ways in which um, like restaurants or like churches exist with like health codes, it’s hard for us to bring food in and find safe places to store food, so that’s our biggest concern about … getting food. (Food Rescue 1)

[Do they] hav[e] containers in order to accept it … I don’t know if their facility has like a thermometer to even test the temperature and hold it at a certain temperature, which are part of the food standards, like from a serving perspective. (Caterer 2)

In contrast to the strict rules governing temperature regimes, best before dates in Canada are not as stringently regulated. Processors are only required to place best before dates on packaged food items with an expected shelf-life of less than 90 days. Anything that would be expected to last more than 90 days is considered shelf-stable and does not require a best before date, although these items are often labelled with best before dates as well (Canadian Food Inspection Agency Citation2015). The process of determining best before dates is also vague and unregulated. There are no regulatory requirements for manufacturers to test for microbial growth or otherwise substantiate the chosen best before dates. Consumers in our study locale often use best before dates as an indicator of when food becomes waste (Parizeau et al. Citation2015), suggesting that these labels are mistaken for expiry dates. Very few items in Canada bear actual expiry dates (including nutritional supplements, baby formula, and other items whose nutritional quality may deteriorate after time). Best before dates are therefore inaccurately codified as markers of safety by consumers and in the practices of other actors across the value chain (see Milne Citation2013 for a discussion of this phenomenon in the UK). As one retailer noted:

It’s pretty well dictated for us, most everything is dated nowadays, so you gotta look at expiration dates, we have a policy in place of five days, most things are within five days of a code, we pull it out. (Retailer 2)

The reliance on best before dates as an indicator of food’s safety (i.e. the material absence of dangerous levels of microbes) was often connected to interviewees’ concerns about liability, both in terms of selling food beyond its best before date, and donating it:

In this day and age, everyone’s scared of getting sick somewhere, or from something … It’s all about who’s going to be legally responsible should there be any sort of you know, complication of sickness, illness … it’s unfortunate, but that’s the way it is, people look at us as an opportunity to make an easy buck sometimes (Retailer 1)

I think a lot more places would donate if they weren’t concerned about liability … So meat products are harder, dairy are also harder to get your hands on, um, breads don’t … there’s not as much liability or risk with breads because it’s a shelf stable type item, mostly (Emergency Food Provider 6)

No, the problem with donating stuff is that you could end up with a health issue … If someone gets sick on it, or something that’s off code or poor quality, and someone gets sick then you could have a real issue, so we stay away from that (Retailer 3)

Another example of a food management system that signifies waste is the treatment of recalled food items. These products may be recalled by manufacturers for a number of reasons; sometimes recalls indicate a food safety concern, and sometimes they are the result of packaging mistakes (such as the exclusion of French translations on products sold in Canada). Retail respondents reported that all recalled foods are destroyed to ensure that these foods cannot be reclaimed from the trash by ‘dumpster divers’ in order to prevent illness:

Anytime anything’s recalled there’s a reason it’s being pulled off the shelf. It shouldn’t be edible, and we actually go one step further and actually destroy it, because we do have people who dumpster dive here, and … I would hate for somebody to get sick because of something they took from our dumpsters, so we usually break it up, or put it in a separate bag and one of us will throw it in, something like that (Retailer 4)

Any perishable item that comes back into the building does not hit the shelves … it’s either destroyed or it’s put [aside] for the supplier to pick up, and the same with recalls, we have a really detailed recall program … we’ll get an email from recalls, we have 24 hours to respond electronically, we check the product, we follow the prompt of what to do, throw it out or what to do with it, and then we have to record it, we have actual physical documentation at the service desk, so if anyone from the government comes in, we can produce it for them (Retailer 2)

Food management systems and techniques are a reaction to the inscrutability of the spoilage process itself. While food handlers may be able to assess whether food has visibly spoiled or whether it is still aesthetically pleasing enough to sell, certain types of spoilage are not discernible by the human eye. In particular, the growth of pathogenic microbes is not usually detectable through sight or even smell. Because food-borne illness can be debilitating or even fatal, it is important for food system actors to find ways of protecting against these risks. Cold chain processes, best before dates, and recall protocols represent an attempt to use techniques and systems to prevent the ingestion of spoiled foods, rather than relying on direct assessments of the materiality of the food items themselves:

Say someone returns a package of steaks, you know, you can’t put it back on the sales floor, even though the guy swears, ‘well, I took it home, it was in my fridge the entire time’, you know, because you don’t know if it’s been temperature abused or not (Retailer 1)

So it’s … unavoidable, we temped it, it was … unavoidable. Can we save it? No, it’s been past safety temperatures for too long (Restaurant 1)

The focus on technologies and techniques rather than the materiality of the food itself relieves the individual of the decision-making responsibility. Technology as actant can, therefore, stand in for knowledge and experience pertaining to the material transformation from food to pathogen. Watson and Meah (Citation2013) describe the technology of date labels:

They seek, in effect, to redistribute responsibility, away from the direct relation between consumer and retailer and, more crucially, away from the consumer and their capacity to assess the safety of food through direct sensory engagement. Responsibility is instead assumed by institutional processes of risk assessment and knowledge production. (p. 111)

Material grey zones: is it food or is it waste?

While some techniques and management systems dictate the determination of when food becomes waste across the food value chain, the interviews also revealed that some of the lines that delineate edible food from waste are less clear. For example, excess food that cannot be sold due to market demands may end up unharvested, even though it is edible:

We can’t afford to harvest it and bring it somewhere … and I can’t afford to pay my staff to do that, and then give it away (Producer 5).

If you don’t have a market for what you have to sell, then that’s an area of food waste (Producer 4).

A product’s aesthetics represent a material condition that can also influence its market circulation. Many nutritious and edible produce items never arrive on grocery store shelves due to quality selection and cosmetic standards, thus creating unnecessary waste (Institution of Mechanical Engineers Citation2013). Socio-cultural norms, and to an extent consumers, modulate what food is deemed ‘edible.’ A producer commented on this:

I guess, food that would not be used … would be either like, a quality thing, if we’re harvesting things that are cracked, or deformed, or … in one way or another, not salable, up to our sort of standard, would be left in the field, culled out in processing (Producer 5)

Although the aesthetic appearance of foods may prevent their sale, some retailers will prevent waste in their stores by cutting up and packaging produce that is beginning to spoil, and then selling it for a premium:

Unfortunately, sometimes if our peppers come in and they’re a bit wrinkly, they just … we can’t sell them, so we usually end up, we’ll cut them up, or do something like that, and then we would sell them back [to the customer], and … it’s usually good for our margins as well because you’re usually selling them at a premium price for what you would actually get for them (Retailer 4)

Cut fruit is … about 60% margin. There’s a big process to it, so most of our stores now, cut fruit’s all done in the cut fruit room. They have it all refrigerated, so we go out to the shelf, you take a bunch of stuff off the shelf that looks like - or he’s culled it and it’s going to back and it’s almost ready to be reduce, that gets chilled, and then [they] cut it all up and process it, and put it in the cut fruit … Most of the produce waste went into cut fruit (Retailer 2)

Reclaiming the material value of wasted food

Watson and Meah (Citation2013) highlight the role of disgust in the classification of food as waste. A key informant for the waste sector commented on the particular materiality of food waste:

Sometimes, [it is] not as easy, for the average consumer … their old phone, they keep in a drawer, and they can see some value in that product. The rotten tomato they just want to get out of the house. So there’s a bit of a different public perception around value, when it comes to some of the things that we’re tackling on the waste side (Key Informant 4)

Through composting (aerobic degradation), food waste is converted into fertilizer through the biological activity of microorganisms (Otles et al. Citation2015). This node in waste recovery regimes demonstrates some of the contingencies of material relationality. Micro-organisms can be actants forcing people to throw out food when enrolled in the network of our modern food system; however, in an infrastructure-intensive network dedicated to recovering energy and nutrients from wasted food, micro-organisms can be an agent of climate-change mitigation. The end product of compost improves soil quality by increasing nutrients and water capacity and supporting soil organisms. Producers noted that composting their ‘waste’ on farm provided important nutrient cycling for their fields. Alternatively, food waste can be converted into energy through anaerobic digestion processes. When food is sent to landfills, it is enrolled in a network where it oxidizes, decomposes, and creates methane gas (Otles et al. Citation2015), a powerful greenhouse gas emission, thereby becoming a climate change actant. However, the gas created through the decomposition of food waste could also be captured under a controlled environment, and converted into energy that is recovered as either heat or electricity, if enrolled in a different network with technological treatments. A biogas industry representative noted the opportunity in harnessing the materiality of rotting food:

Taking advantage of that organic material … to divert it to an anaerobic digestion process, which can then capture the energy, recycle and recover the nutrients back to the land and have all of these other ancillary benefits in terms of [the] reduction of methane which helps to improve our GHG emission profile … so there’s a lot of benefits that come from … diverting the organic material. I think the now novel opportunity is to be able to capture that and use the biogas to be able to utilize it as a renewable form of energy (Key Informant 3)

However, food waste recovery can be complex. As Gregson et al. (Citation2015) note, food waste as a feedstock for anaerobic digestion can be problematic; its composition can be seasonally inconsistent, and it is often contaminated with inorganic matter such as plastics and packaging. This means that inputs have to be screened, and in some cases the compost output has to be pasteurized, as even seemingly insignificant amounts of glass or plastic could ruin the end product (Levis et al. Citation2010). As waste expert respondents noted, this adds to the costs of processing food waste. The food waste feedstock network involves not only technological relationality (outputs needing treatment, i.e. pasteurization) but also elements of economic relationality when cost becomes a barrier and feedstocks are contaminated. The propensity for food waste to be accompanied by plastic and other contaminants can also disrupt its diversion to animal feed:

[You have to] make sure there’s no … crap in that bin … and just keep it proper, that’s gonna be pig food, so no like, egg shells, no … no paper or plastic that should have gone in the garbage as you’re doing stuff too fast and throw it in there, no, just keep proper, cuz that’s going to a pig … So that’s going to affect the pig’s life (Restaurant 1)

Food waste treatment can also be problematic because of the abjection inherent to food waste: for example, organics waste management may come with odour concerns. In interviews, both a waste management expert and an anaerobic digestion facility manager noted the difficulties in developing organic waste processing facilities. Additionally, capital-intensive infrastructure is needed to build anaerobic digestion facilities, and organic waste would ideally be source-separated and collected apart from other waste streams in order to facilitate nutrient and energy recovery. End markets need to be developed for the end products, especially biogas, as noted by the waste management respondents. If used for vehicle fuel, as promoted by the anaerobic digestion facility respondent and the biogas industry representative, vehicles then need to be adapted to accept this type of fuel. As Gregson et al. (Citation2015) note, the end products of digestate and biogas are still relatively new materials, and the safety and usefulness of these end products need to be ensured in order to develop a successful market for them. As Alexander et al. (Citation2013, p. 481) note, all of these changes depend on a ‘complex assemblage of legislation, capital mobilization, infrastructure, households, and additional technologies.’

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated how the relational aspects of food waste materiality impact its circulation and disposal across the food value chain. Food’s capacity to grow mould, rot, make us sick, and release methane are all examples of how food waste has agency and captures the behaviour of humans. Food waste also demonstrates agency in relation to the actors and systems that surround it. For example, the inherent tendency for food to spoil quickly necessitates the creation of storage and transportation infrastructures to prolong its edibility, highlighting the centrality of temporality in the materialities of food waste. The inscrutability of when rotting food becomes dangerous combined with risk avoidance on the part of retailers and consumers has engendered the creation of food management systems that displace the need for direct assessments of food’s materiality, thus allowing for the deskilling of food workers and consumers who no longer need to decide for themselves whether food is safe. The nuisance aspects of rotting food lead to human abjection and the desire to be rid of it quickly; however, the resource potential of organic waste has also led to the creation of treatment facilities to recover nutrients and energy from food waste.

We have demonstrated that food waste is relationally defined in the food value chain, and that socio-cultural norms and other systematic factors are central to determinations of when food has transformed into waste. Food may become waste by transgressing food management system boundaries (such as temperature regimes or best before dates), by not meeting aesthetic standards that are set by retailers or internalized by consumers, or by not finding a market at a time when the foodstuff is still vital. The transformation from food to waste is not unidirectional, however. Respondents described how culled produce could be rehabilitated into higher-margin processed products at retail, and allusions to dumpster divers indicates the presence of counter-culture actors who also seek to reclaim food value from waste. Such interventions can be understood as interruptions of traditional wasting practices that disrupt socially-constructed definitions of waste. Advocacy efforts by organizations like the National Zero Waste Council also seek to disrupt widespread narratives and practices that lead to high rates of food waste generation in Canada. We can also understand the obstinate tendency of food to rot as a form of interruption: despite the efforts of actors across the food value chain to prevent spoilage and to divert food to alternate uses, it sometimes becomes inedible anyway.

The paths travelled by food are an indicator of its diverse vitalities: sometimes food that is not sellable at retail or in food service can be donated to emergency food providers, and sometimes these actors are not able to recover its edibility. Sometimes food can be diverted to animal feed, but the tendency for foodstuffs to be accompanied by plastic packaging and other contaminants can render it less vital for this purpose as well. The potential for contamination can also impact the compostability/digestability of organic waste, although new technologies are arising to address this challenge as the resource potential of food waste is increasingly realized. The absent-presence of microbes is another form of vitality that often ‘haunts’ food, and contributes to its designation as waste.

We are disconnected from our food and our waste systems (Hultman and Corvellec Citation2012). Food waste is something to be removed quickly and not thought of again. As de Coverly et al. (Citation2008) note, we are socialized to think that waste should not be visible in public spaces. Our current food system operates at a global-scale, whereby food production chains are lengthy and far removed from where purchasing and consumption occur, and industrial supply chains are not transparent to consumers (Alexander et al. Citation2013, Watson and Meah Citation2013). This in itself exacerbates food waste and demonstrates the importance of temporality in this relational network: when supply chain networks are disrupted (for example, through transportation or refrigeration issues), perishable items become waste (Alexander et al. Citation2013). The industrial food system also results in a lack of knowledge of where food comes from and how it is produced, ultimately requiring technological intervention to assist with the determination of when food is still edible. This is exemplified by the widespread expectation that food looks ‘perfect,’ as well as the implementation of best before dates by food manufacturers, whereby responsibility and knowledge of food safety are shifted from the consumer to what we assume as ‘microbiological expertise’ (Milne Citation2013, p. 94).

An important idea that emerges from this research is that the relational agency of food waste is dependent on its material states: edible material can be recovered or repurposed as food for humans or animals, and inedible food waste is useful when it can be composted and returned to the earth as nutrients for growing more food or processed in a way to create renewable fuel. However, when organic materials are landfilled, they create a potent greenhouse gas and represent economic losses. The multi-potentiality of the impacts of food waste is starting to affect how our society engages with this material, and pressure us to prevent the landfilling of organic matter. Perhaps one of the most pressing exertions of food waste’s agency is the way in which it responsibilizes us as social actors to prevent the harms it may cause.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Alexis Van Bemmel holds an undergraduate degree from the University of Victoria in Geography with a specialization in Environmental Sustainability, and a graduate degree from the University of Guelph in Geography, focusing on sustainable food and waste systems. Alexis currently works for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada on conservation measures and sustainable fisheries.

Kate Parizeau is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography, Environment & Geomatics at the University of Guelph. She studies the social context of waste and its management.

References

- Alexander, C., Gregson, N., and Gille Z., 2013. Food waste. In: A. Murcott, W. Belasco and P. Jackson, eds. The handbook of food research. London: Bloomsbury, 471–483.

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., et al., 2015. Consumer-related food waste: causes and potential for action. Sustainability, 7 (6), 6457–6477. doi:10.3390/su7066457.

- Bagherzadeh, M., Inamura, M., and Jeong, H., 2014. Food waste along the food chain. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, 71. doi:10.1787/5jxrcmftzj36-en.

- Bakker, K. and Bridge, G., 2006. Material worlds? resource geographies and the “matter of nature”. Progress in Human Geography, 30 (1), 5–27. doi:10.1191/0309132506ph588oa.

- Bennett, J., 2007. Edible matter. New Left Review, 45, 133–145.

- Bosco, F.J., 2006. Actor-network theory, networks, and relational approaches in human geography. In: S. Aitken and G. Valentine, eds. Approaches to human geography. London: SAGE Publication, 136–146.

- Buzby, J.C., et al., 2011. The value of retail-and consumer level fruit and vegetable losses in the United States. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 45 (3), 492–515.

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2015. Date marking and storage instruction requirements. Available from: http://www.inspection.gc.ca/food/labelling/food-labelling-for-industry/datemarkings-and-storage-instructions/eng/1328032988308/1328034259857?chap=1.

- Carenzo, S. and Good, C., 2016. Materiality and the recovery of discarded materials in a Buenos Aires cartonero cooperative. Discourse, 38 (1), 85–108. Available from: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/626073.

- City of Guelph, 2017. Solid waste management master plan. Available from: https://guelph.ca/plans-and-strategies/solid-waste-management-master-plan/.

- Cockerill, K., et al., 2017. The unpredictable materiality of radioactive waste. In: K. Cockerill, M. Armstrong, J. Richter and J.G. Okie, eds. Environmental realism. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 67–87. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52824-3_4.

- Coles, B. and Hallett, L., 2012. Eating from the Bin: salmon heads, waste and the markets that make them. Sociological Review, 60 (2), 156–173. doi:10.1111/1467-954X,12043.

- Corvellec, H., 2016. Sustainability objects as performative definitions of sustainability: The case of food-waste-based biogas and biofertilizers. Journal of Material Culture, 21 (3), 383–401. doi:10.1177/1359183516632281.

- Corvellec, H. and Hultman, J., 2012. From “less landfilling” to “wasting less”. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25 (2), 297–314. doi:10.1108/09534811211213964.

- de Coverly, E., et al., 2008. Hidden Mountain: The social avoidance of waste. Journal of Macromarketing, 28 (3), 289–303. doi:10.1177/0276146708320442.

- Eriksson, M., Strid, I., and Hansson, P., 2015. Carbon footprint of food waste management options in the waste hierarchy – a Swedish case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 93, 115–125. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.026.

- Evans, D., 2011. Blaming the consumer – once again: The social and material contexts of everyday food waste practices in some English households. Critical Public Health, 21 (4), 429–440. doi:10.1080/09581596.2011.608797.

- Evans, D., Campbell, H., and Murcott, A., 2012. A brief pre-history of food waste and the social sciences. The Sociological Review, 60, 5–26. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12035.

- FAO, 2013. Food waste harms climate, water, land and biodiversity. Available from: http://www.unep.org/newscentre/default.aspx?DocumentID=2726&ArticleID=9611.

- Fehr, M., Calçado, M.D.R., and Romão, D.C., 2002. The basis of a policy for minimizing and recycling food waste. Environmental Science & Policy, 5 (3), 247–253. doi:10.1016/S1462-9011(02)00036-9.

- Felfel, A. and Rich, T., 2015. An overview of Canadian food loss and waste estimates. Ottawa, ON: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Available from: https://www.brandonu.ca/rdi/files/2014/03/Abdel-Presentation2.pdf.

- Fraser, C. and Parizeau, K., 2018. Waste management as foodwork: A feminist food studies approach to household food waste. Canadian Food Studies, 5 (1), 39–62. Available from: http://canadianfoodstudies.uwaterloo.ca/index.php/cfs/article/view/186/224.

- Gille, Z., 2010. Actor networks, modes of production, and waste regimes: Reassembling the macro-social. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42 (5), 1049–1064. doi:10.1068/a42122.

- Gille, Z., 2013. Is there an emancipatory ontology of matter? A response to Myra Hird. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, 2 (4), 1–6. Available from: https://socialepistemologydotcom.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/gille_reply_hird2.pdf.

- Gobel, C., et al., 2015. Cutting food waste through cooperation along the food supply chain. Sustainability, 7 (2), 1429–1445. doi:10.3390/su7021429.

- Gooch, M. and Felfel, A., 2014. “$27 Billion” revisited: The cost of Canada’s annual food waste. Value Chain Management Centre. Available from: http://vcm-international.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Food-Waste-in-Canada-27-Billion-Revisited-Dec-10-2014.pdf.

- Goodman, M.K., 2016. Food geographies I: relational foodscapes and the busy-ness of being more-than-food. Progress in Human Geography, 40 (2), 257–266. doi:10.1177/0309132515570192.

- Graham-Rowe, E., Jessop, D. C., and Sparks, P., 2014. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 84, 15–23. doi:10.1016/J.RESCONREC.2013.12.005.

- Gregson, N. and Crang, M., 2010. Materiality and waste: inorganic vitality in a networked world. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42 (5), 1026–1032. doi:10.1068/a43176.

- Gregson, N., et al., 2010. Following things of rubbish value: end-of-life ships, ‘chock-chocky’ furniture and the Bangladeshi middle class consumer. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 41 (6), 846–854. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.05.007.

- Gregson, N., et al., 2015. Interrogating the circular economy: the moral economy of resource recovery in the EU. Economy and Society, 44 (2), 218–243. doi:10.1080/03085147.2015.1013353.

- Gustavsson, J., et al., 2011. Global food losses and food waste: Extent, causes and prevention. Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology (SIK) and FAO. Available from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/mb060e/mb060e02.pdf.

- Halloran, A., et al., 2014. Addressing food waste reduction in Denmark. Food Policy, 49, 294–301. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.09.005.

- Hawkins, G., 2009. The politics of bottled water. Journal of Cultural Economy, 2 (1-2), 183–195. doi:10.1080/17530350903064196.

- Hepp, C., 2016. The food waste paradox from a critical discursive perspective. Lund University. Available from: http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8873321&fileOId=8873604.

- Hultman, J. and Corvellec, H., 2012. The European waste hierarchy: from the sociomateriality of waste to a politics of consumption. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44 (10), 2413–2427. doi:10.1068/a44668.

- Institution of Mechanical Engineers, 2013. Global food: waste not, want not. [Online], pp 1–31. Available from: http://www.imeche.org/policy-and-press/reports/detail/global-food-waste-not-want-not.

- Jol, S., et al., 2007. The cold chain, one link in Canada’s food safety initiatives. Food Control, 18 (6), 713–715. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2006.03.006.

- Kantor, L.S., et al., 1997. Estimating and addressing America’s food losses. Food Review, 20, 2–12.

- Katajajuuri, J.M., et al., 2014. Food waste in the Finnish food chain. Journal of Cleaner Production, 73, 322–329. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.12.057.

- Khoo, S.M. and Rau, H., 2009. Movements, mobilities and the politics of hazardous waste. Environmental Politics, 18 (6), 960–980. doi:10.1080/09644010903345710.

- Levis, J.W., et al., 2010. Assessment of the state of food waste treatment in the United States and Canada. Waste Management, 30 (8/9), 1486–1494. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2010.01.031.

- Liboiron, M., 2016. Redefining pollution and action: the matter of plastics. Journal of Material Culture, 21 (1), 87–110. doi:10.1177/1359183515622966.

- Lipinski, B., et al., 2013. Reducing food loss and waste. World Resources Institute. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.360.951&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Magnani, N., 2012. Nonhuman actors, hybrid networks, and conflicts over municipal waste incinerators. Organization & Environment, 25 (2), 131–145. doi:10.1177/1086026612449337.

- Marshak, M., 2012. Systems in transition: from waste to resource: a study of supermarket food waste in Cape Town. Thesis. University of Cape Town.

- Mena, C., Adenso-Diaz, B., and Yurt, O., 2011. The causes of food waste in the supplier–retailer interface: Evidences from the UK and Spain. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 55 (6), 648–658. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.09.006.

- Milne, R., 2013. Arbiters of waste: date labels, the consumer and knowing good, safe food. Sociological Review, 60 (2), 84–101. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12039.

- Moore, S., 2012. Garbage matters: concepts in new geographies of waste. Progress in Human Geography, 36 (6), 780–799. doi:10.1177/0309132512437077.

- Murdoch, J., Marsden, T., and Bank, J., 2000. Quality, nature, and embeddedness: some theoretical considerations in the context of the food sector. Economic Geography, 76 (2), 107–125.

- National Zero Waste Council, 2018. A food loss and waste strategy for Canada. Available from: http://www.nzwc.ca/focus/food/national-food-waste-strategy/Documents/NZWC-FoodLossWasteStrategy.pdf.

- Nikkel, L., et al., 2019. The avoidable crisis of food waste: roadmap. Second Harvest and Value Chain Management International. Available from: https://secondharvest.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Avoidable-Crisis-of-Food-Waste-The-Roadmap-by-Second-Harvest-and-VCMI.pdf.

- Otles, S., et al., 2015. Food waste management, valorization, and sustainability in the food industry. In: C.M. Galanakis, ed. Food waste recovery: processing technologies and industrial techniques. London: Elsevier, 3–24.

- Parfitt, J., Barthel, M., and Macnaughton, S., 2010. Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365 (1554), 3065–3081. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0126.

- Parizeau, K., Von Massow, M., and Martin, R., 2015. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Management, 35, 207–217.

- Prakash, V., et al., 2014. Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems. Rome: FAO. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3901e.pdf.

- Sayes, E., 2014. Actor-network theory and methodology: just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency? Social Studies of Science, 44 (1), 134–149. doi:10.1177/0306312713511867.

- Statistics Canada, 2018. Census Profile, 2016 Census. Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

- Stuart, T., 2009. Waste: uncovering the global food Scandal. London: Penguin Books.

- Thyberg, K.L. and Tonjes, D.J., 2016. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 106, 110–123. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.016.

- Uzea, N., Gooch, M., and Sparling, D., 2013. Developing an industry led approach to addressing food waste in Canada. Report. Guelph, ON: Provision Coalition. Available from: https://provisioncoalition.com/assets/website/pdfs/Provision-Addressing-Food-Waste-In-Canada-EN.pdf.

- Waitt, G. and Phillips, C., 2016. Food waste and domestic refrigeration: a visceral and material approach. Social & Cultural Geography, 17 (3), 359–379. doi:10.1080/14649365.2015.1075580.

- Watson, M. and Meah, A., 2013. Food, waste and safety: negotiating conflicting social anxieties into the practices of domestic provisioning. The Sociological Review, 60 (2), 102–120. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12040.