ABSTRACT

This article explores the notion of ‘epistemic distances,’ which are operationalised by acts of showing as well as omitting. It is investigated through practices of market research where researchers aim to overcome a perceived lack or absence of market knowledge. However, such work relies on keeping clients and respondents away from many details of how the research is undertaken. Based on anthropological fieldwork, this article inquires into how the staff members of a market research firm limit what their clients and respondents know. Such study of the role of secrecy and non-knowledge in commissioned knowledge production takes its cue from the anthropology of secrecy and the agnotological study of ignorance. Further, the article draws on spatial imaginaries in constructivist market studies as well as the study of the role of distance and difference in understanding in science and technology studies. The text contributes to the understanding of knowledge making by showing how market research features epistemic as well as relational concerns. These are handled through the active managing of epistemic distances by shaping what involved actors know. The gap between current and desired knowledge is sometimes met only by maintaining distance.

Introduction

This article deals with the role of distance metaphors in the making of knowledge. Motifs include efforts to ‘close gaps’ in market knowledge as well as to manage relationships between knowledge producers and recipients by means of omission. In order to discuss the role of relations in knowledge production, I suggest the notion of ‘epistemic distance,’ which I explore through examples from market research practice. Involved in commissioned knowledge production (Nilsson Citation2018b), market researchers make it their business to produce a particular kind of material – marketing knowledge – for recipients to use. This is typically framed as work to close or overcome gaps in knowledge about markets, or providing a link between the client and consumers (cf. Lien Citation2004). However, market researchers may keep both clients and the respondents they study ignorant regarding many details of the research work. Indeed, market researchers may consider this work to both overcome and to maintain ignorance as complementary. Such action is framed as useful not only for pursuing their own business interests but also to ensure that clients truly receive useful information.

Empirically, I draw on how a group of market researchers shape what their clients and study respondents know. This shaping is explored both in the sense of producing knowledge qua useful market representations (Ruiz and Holmlund Citation2017) and through different kinds of ‘non-knowledge’ – a phrase denoting both the limits and absence of knowledge (Proctor and Schiebinger Citation2008). This dual attention stems from the tensions and ambiguities within market research as an activity: it involves both making knowledge and managing ties with clients (Nilsson Citation2019; Citation2018b). As such, it features the overcoming of distances and the production of insight but also work to keep clients and respondents at arm’s length. My discussion is based on ethnographic study with a Swedish branch of an international market research firm, which I call Norna. I have interviewed staff members, assessed work materials and undertaken participant observation (Davies, Citation2012) to find out how the distribution and making of information is handled though the market research process.

Following the tradition of constructivist market studies (e.g. Araujo et al. Citation2010), this article approaches the making of market knowledge as an activity that plays a part in shaping the phenomena it purportedly describes (Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015). Marketing ‘knowledge’ is fruitfully approached as representations (see Ruiz and Holmlund Citation2017) that cannot be readily disentangled from the methods through which they have come about (Law Citation2004). Given interest in how market researchers seek to do business by filling particular needs for knowledge, I turn to studies of knowledge as unequally distributed and socially shaping (Barth Citation1990, Barth et al. Citation2002). As market researchers rely on keeping things unknown for the sake of informing their clients, I also draw on scholarship about non-knowledge as constitutive for understanding (e.g. Proctor Citation2008). I explore the ambiguous work to both overcome and (re)produce distances between the actors involved in market research and how this relates to the production of knowledge. This further develops perspectives on how market research seeks to pursue social relationships in the form of business interests and epistemics qua research concerns in tandem (Nilsson Citation2018b).

This article turns to the case of market researchers at Norna, pursuing the question: How are tensions between closing and maintaining distances vis-à-vis research participants and clients handled by means of shaping knowledge and non-knowledge? Drawing on interest in science and technology studies (STS) about how distance affects understanding of scientific results (MacKenzie Citation1990, Collins Citation1997, Latour Citation1999), I argue that distances between researchers, respondents (i.e. research participants) and recipients (i.e. clients) are shaped by market researchers in order to foster certain kinds of knowledge reception and relationships. The article contributes to scholarship about the making of marketing knowledge (Bjerrisgaard and Kjeldgaard Citation2013, Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015, Ruiz and Holmlund Citation2017) by showing how such work involves the making of results and reports as well as affecting relationships.

Background to market research as knowledge production

Knowledge as a cultural phenomenon is best studied through its workings: how knowledge is made, distributed, kept and drawn on (Barth et al. Citation2002). This includes the role played by practices, models and ideas in producing research results (Helgesson et al. Citation2016) and knowledge about markets (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2007, Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015). The area of research has focused on the role of economics (MacKenzie Citation2008, Steiner Citation2010) as well as marketing (Kjellberg and Helgesson Citation2007, Araujo et al. Citation2010) in enacting markets (Callon Citation1998). Such scholarship stresses that markets and market knowledge are mutually shaped and shape each other and that results cannot be readily separated from processes of making and describing. This includes studies of how markets are achieved (Callon Citation1998) and how objects of marketing knowledge are performed in the methods used to describe them (Heiskanen Citation2005, Muniesa and Trébuchet-Breitwiller Citation2010). Further, research into the making of market research reports stress that simplification (Diaz Ruiz Citation2013) and the shaping of recipients’ interpretations (Ruiz and Holmlund Citation2017, Nilsson Citation2019) play a major role in the usefulness of such representations. Given this attention to models and ideas for the outcomes of knowledge production there is reason to think about how actions towards meeting knowledge needs are expressed – not just in marketing settings but in other fields of knowledge production. This article adds to the extant scholarship on the workings of market knowledge by acknowledging how metaphors of gaps, space and distance are utilised to produce desired outcomes.

The role of spatial metaphors in knowledge making

For the purpose of inquiry into how market research addresses knowledge gaps, it is worth considering how ideas about markets and the need to know them are expressed. Anthropologist Marianne Lien (Citation2004), who has studied marketers in Norway, notes that marketing knowledge is produced to address gaps in knowledge as if research is about bridging distances. The marketers she portrays refer to the lack of connection to actual consumers as motivation for continuous marketing research. The undertaking of research offered the chance for closer interaction and direct experience with the otherwise distant targets of marketing work (Lien Citation2004). Spatialised notions of market and marketing knowledge are also inferred by project process models and other managerial tools that outline the process of going from data about the world to knowledge, and from research situation to client (Moisander and Valtonen Citation2006, Bjerrisgaard and Kjeldgaard Citation2013, Kotler et al. Citation2016, Ladner Citation2014).

A further analysis of the role of gaps and absences in knowledge making may be found in STS works that conceptualise distance in understanding. For example, Donald MacKenzie (Citation1990) has observed that results in science and technology tend to be understood differently by those closely involved in making them than by those with less access to the practices of such knowledge production. Uncertainty over results is high among those directly involved in designing and testing technologies (where uncertainties and snags are well-known). This uncertainty then decreases in the case of actors with more passing knowledge (such as managers championing the results), only to increase again in those alienated entirely from knowledge production. Similarly, Harry Collins (Citation1997) has noted that understanding of scientific results differs between groups of actors. Although involved researchers, other ‘scientifically literate’ experts, policy makers and ‘the public’ may hold similar opinions in a scientific controversy, their understanding of science and its imperfections may vary (Harry Collins Citation1997). Both MacKenzie (Citation1990) and Collins assume a difference that is framed in terms of distance.

Importantly for this investigation, Collins as well as MacKenzie refer to spatialised notions of a separation of actors as a given condition, rather than something that is actively managed by the actors involved. Their observation of a sort of ‘epistemic distance’ (Nilsson Citation2018b) is useful to this inquiry, however. For one thing, it resonates with the implication that research bridges some kind of distance between decision makers and the world as expressed by Lien’s (Citation2004) marketers or the models used for global trend analysis discussed by Bjerrisgaard and Kjeldgaard (Citation2013). Ideas about research spanning distances are also expressed in knowledge models where ‘data’ out in the world is turned into ‘information’ that can subsequently be turned into ‘knowledge’ and then ‘wisdom’ or ‘insight’ of the recipients (Rowley Citation2007). Often such models describe a one-way direction of the analysis process (Räsänen and Nyce Citation2013). The process connects the world to the recipients of knowledge, across a series of related steps and involved actors (e.g. research respondents; researchers and their tools of analysis; receiving clients) to produce increasingly abstract representations (see also Latour Citation1999, Ruiz and Holmlund Citation2017). Attention to spatiality in knowledge making is useful for this article’s inquiry into how gaps in knowledge are addressed. With gaps overcome through processes that feature active omission and the maintenance of distance, there is reason to look further into how knowledge can be approached as distributed and shaping social relationships.

The (unequal) distribution of knowledge

Anthropological concerns over knowledge have come to include not merely that which is treated as knowledge but also that which is not. For instance, in his study of secret knowledge in Melanesia and south Asia, Anthropologist Fredrik Barth has stressed how knowledge in a society is unequally distributed, both through modes of communication and withholding (Barth Citation1990). Keeping knowledge from other people is approached as useful in enacting social distance: uneven distribution of knowledge may shape social relationships by designating who knows what. Here, Barth suggests how shaping the spread of what is known, or the right to know, distributes knowledge, power and influence in society in a manner that sets (groups of) people apart. Withholding information and maintaining secrecy constitute a useful tool for inclusion and exclusion. Market research entails much effort to produce social relationships between client and research as part of the work (see Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015, Nilsson Citation2019). While the role of knowledge in shaping social relationships is important to this inquiry, the making and interpretation of knowledge are also central concerns. This spurs attention to the role of shaping understanding through what is kept unsaid and thus unknown in order to connect social and epistemic concerns in market research.

How what is not known shapes understanding

Adding to interest in how knowledge affects social formation there are also important strains of research that explore the limits of knowledge. Cases include deliberate omission, identified lacks of knowledge, or simply the unknown. Agnotology is the study of how such ‘non-knowledge’ plays a part in shaping our understanding of what we know: limitations make knowledge possible by framing interests and interpretations (Proctor and Schiebinger Citation2008). While the anthropological analysis of secrecy may assume knowledge or an underlying truth (e.g. Manderson et al. Citation2015), the anthropology of ignorance (High et al. Citation2012), agnotology studies (Proctor and Schiebinger Citation2008) and ignorance studies (Gross and McGoey Citation2015) instead treat states of knowing and not knowing in a more symmetrical fashion. For instance, Proctor and Schiebinger (Citation2008) note the widespread assumption of knowledge as a teleological point of arrival, and ignorance or other forms of non-knowledge as gaps to be filled. Alternatively, they suggest that non-knowing and the non-known are to be studied as located and achieved phenomena (Proctor and Schiebinger Citation2008).

Acts of omission are possible to see in terms of distributing ignorance which both affects social relationships and makes certain knowledge and understanding possible. There are many times when someone does not want to, or ought not to, know of things (Gross and McGoey Citation2015). Leaving things out or maintaining secrets is not just obscuring truth, but may act to make statements of fact compelling, both in the sense of being convincing and being comprehensive. Rappert et al. (Citation2011) describe how anti-cluster bomb activists struggle with government secrecy, but also how they use and make accounts more useful for their purposes through acts of omission. Their article further argues for the value of looking into state secrecy, not merely as a negative issue to be mitigated by the researchers’ exposure, but rather as something that can be used as both an analytic resource and important social cueing in the analysis of secrecy: ‘the overt partial disclosure given here could be interpreted as contributing both to the ignorance and understanding of readers’ (Rappert et al. Citation2011). Ignorance about certain things may be fostered in order to strengthen recognition on the part of recipients, and audiences may well be privy to a form of ‘meta-ignorance’ in knowing the extent of what they do not know (Rappert et al. Citation2011). Simply put, Rappert et al. suggest treating omission as a way to shape understanding.

Tools for investigating market research as the shaping of non-knowledge

This article relates the study of market researchers to scholarship on the making of marketing knowledge, spatial metaphors of knowledge making, and study of how knowledge is intimately connected with non-knowledge through omission. Previous research suggests attention to how knowledge is shaped, partially through spatial notions and models. It also urges further research into how this spatiality relates to knowledge and the unknown. Market researchers may be aware of details that may best be omitted in order to decrease uncertainty on the part of clients and make sure that clients are down in the ‘trough’ of low uncertainty (MacKenzie Citation1990). Indeed, a feeling of certainty of information may foster better propensity for decision making (Ruiz and Holmlund Citation2017, Nilsson Citation2019). The spatial relation that is treated as a constant by Collins (Citation1997) and MacKenzie (Citation1990) may well be explored as more dynamic. Attention to distances of social relations and knowledge as intertwined offers an alternative to ideas of knowledge gaps as merely overcome in the making and exchange of market knowledge. Over the following sections, I inquire into how epistemic distances are managed by inducing non-knowledge about certain parts of knowledge making.

Methodological approach

This exploration of practices to limit knowledge in the production of market research is based on six months’ of ethnographic fieldwork at the Swedish firm Norna (pseudonym). This market-leading firm has a long history and wide national recognition. Currently it is part of a larger international marketing group with sister research companies across the world. I followed the work of one particular Norna department – Consumption and Technology (C&T), which employs roughly 20 staff. C&T does quantitative and qualitative research for commissioning clients in consumer services and products, including banking, IT and fast-moving consumer goods. Divided into three primary professional categories (project managers, account managers and experts in qualitative methods) the C&T employees are typically university educated professionals, often with a business or psychology profile. I have assigned aliases to my interlocutors according to role: account managers have names starting with an A, project managers’ names start with a P and experts in qualitative methods have aliases beginning with an E.

In order to get a full picture of the work process at C&T I took part as much as I could in the ongoing market research projects during my time at Norna. I collected material from eight projects, including active participation in research and analysis of online focus groups on active-wear and interviews on consumer banking, as well as helping out in drink taste testing. I also collected work documents and did follow-up interviews with the researchers involved in online consumer survey projects and audience testing of TV programming. Notes from work meetings, analysis of research situations (and their results), documents and presentations were then assessed together with interviews conducted with all employees in the department. In total, I undertook 28 semi-structured interviews that were recorded and subsequently transcribed. Research materials featured initial analysis in the structuring of field notes, collected documents and transcripts. The notes were subsequently coded thematically (Saldana Citation2012) using NVivo software. Initially, I coded for content in terms of situations, activities, actors and topics. Recurring rounds of coding further identified analytical themes – especially those relating to work processes, ideas about knowledge and clients (cf. Nilsson Citation2019, Citation2018a).

I mostly had access to parts of the work process as it is described by Norna manuals and presentations. I was unable to attend sales meetings, or presentations with the client; but I sat in on initial client meetings, interactions with respondents and client representatives, analysis meetings, preparation meetings ahead of client presentations and decompression meetings after the presentations. This restriction on the scope of the material is not merely a limitation, but a condition which calls for questioning what comes to be considered research and what comes to be excluded.

The ethnographic section of this article will follow the steps of Norna’s stated progression in a project. It is through these steps that my interlocutors organise knowledge production (cf. Helgesson et al. Citation2016). It is also the way in which knowledge making and its transfer is communicated with clients (cf. Bjerrisgaard and Kjeldgaard Citation2013). As such, they offer a concise overview of work processes. Norna’s own models highlight methodological research stages rather than activities to anticipate and persuade clients. The following sections will discuss these activities, while also paying attention to acts of limiting what research respondents and receiving clients know. In doing so, I seek to engage with, rather than reproduce (Pollock and Williams Citation2016), the epistemics into which I inquire (Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015). I use vignettes and examples from a couple of projects, and interview situations to make a form of bricolage (Lévi-Strauss Citation1966) of what it means to make knowledge in this setting. Presenting a number of different project situations according to this narrative helps to focus on how my interlocutors express, and perform, knowledge as well as non-knowledge, on the part of themselves, respondents and clients. After describing the project processes, I turn to how Norna researchers reflect on knowledge making and how it involves omitting information.

An account of market research projects at Norna

The market researchers at Norna have a straightforward solution to the conundrum of how knowledge is made. They have a model project process that is readily communicated in PowerPoint presentations, to both clients during the sales process and to new employees. According to the process, the work of completing a project (which tellingly omits the selling of the project in the first place) includes several steps in a linear progression. For the purpose of analysis, I have combined these steps into broader stages, reminiscent of how marketing textbooks tend to characterise market research processes (cf. Moisander and Valtonen Citation2006, Belk et al. Citation2012). These broader steps are also observed by the Norna project process in how the steps are colour-coded in five sequential colours.

Preparation (‘Preparation’; ‘Start-up’)

Set-up (‘Working out forms’; ‘Scripting’)

Fieldwork (‘Fieldwork start’; ‘Supervise fieldwork’; ‘Ordering figures and tables’; ‘End of fieldwork’)

Sorting and analysis (‘First draft of report’; ‘Develop report draft’; ‘Analysis’; ‘Insights’; ‘Preparations for presentation’)

Presenting (‘Presentation’; ‘Evaluation’)

As shown by previous research into the making of marketing knowledge (e.g. Heiskanen Citation2005, Muniesa and Trébuchet-Breitwiller Citation2010, Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015, Nilsson Citation2018a), routines and models for undertaking research shapes the knowledge that is produced by establishing what to look for, what to observe and how to analyse it. The stages of Norna’s project process emphasise some parts of undertaking market research while excluding other well-recognised aspects. For example, neither discussions with the client meant to define the project (before as well as during a project), nor sales negotiations are included. Further, the uptake and wise decisions and actions on the part of the client that research purportedly informs are also left out. What the process provides is a model with a beginning, middle and end, where preparations are made and results are gathered, refined and presented in order to give answers to a question and thereby address a certain need for knowledge.

Stage 1: preparation

According to Norna’s project process, the initial phase of a research project contains ‘preparation’ and ‘start-up,’ respectively. During these steps, the project undergoes initial planning. To a project manager who may not necessarily be involved in sales efforts or other client contacts preceding the research, it may be the first stage of the project.

As part of my fieldwork, I participated in a bank card project undertaken by several of Norna’s branch offices in a number of European countries. Commissioned by a card company, the project dealt with the customers of a particular Nordic bank. A project member told me that the study was commissioned to strengthen the card company’s ties with their banking client, possibly through documented joint research on the bank’s customers. The planned study consisted of interviewing a number of premium segments of the bank’s customers, to assess their preferences and habits when it comes to card payment. The set-up meeting with the client took place in the client’s offices, with client representatives (an account manager, an insight manager and a representative from corporate headquarters), Eric (the expert in qualitative methods), representatives from the other Norna offices present on speaker phone, and me.

A manager from one of the Nordic sister branches of Norna began complaining about the overly long interview guide which had been agreed between the commissioning Norna office and the client. That issue had been recognised by the C&T team as well, but Eric chose to keep mum about it. As the complaining researcher kept raising the issue the client’s insight manager appeared more and more flustered and finally blurted out that ‘it’s an interview guide, not a script!.’ After the meeting Eric said that he was pleased that he was not the bearer of bad news; he would not have raised the guide, but he was happy it was brought to the table. While the issue was an uncomfortable one to bring up, there is some room for disregarding particular questions in a research project, as long as the client can be provided with adequate answers to them. In this manner, the list of questions is not necessarily seen as a script but a list of what type of answers the client should have answers for by the end of the project. The insight manager’s comment further suggests that the relative open-endedness of the interview guide is a rather well-known secret (Barth Citation1990). For the sake of getting things done, the client representative wants to maintain the specified questions, but may tacitly accept that the actual interviewing may be undertaken in a more pragmatic manner.

Limitation of knowledge also happens in other parts of the research. Details that may be communicated only selectively to Norna’s clients include the exact composition and capabilities of the project group. During a project on active-wear, account manager Alice had brought in other researchers as experts on a particular segmentation method involving projective interviewing. These researchers presented the merits of particular methods to be used in the study, but because of scheduling and specialised competence they were not always the people who would actually oversee the application of such methods. Instead, the projects could rely on colleagues who did not feature as part of the communicated project team. This situation, with certain researchers as spokespersons and others as executors, was not conveyed to the client during set-up or later on in the project. Such managing of information may be relatively pragmatic and business oriented: market researchers want to maintain a level of distance as part of client contact.

Stage 2: set-up

The set-up stage involves writing up detailed questions (when not already decided, as in the bank card project), deciding on stimuli for product tests, putting together screening forms for selecting respondents, etc. The overall study design tends to be decided on before the project is even formally started, as part of the sales negotiations between account managers and clients. However, many decisions about eventual execution of focus groups, interviews, or surveys, are made during set-up. The details of an interview guide or survey questionnaire, or the make-up of participants, affect the outcome of a project beyond the parameters of a client’s interest and pre-set project goals.

The practice of leaving out the name of the client in respondent recruitment is a prime example of how information is limited during the set-up period. Although not necessarily the case – some qualitative market researchers discourage the practice of leaving out the name of the client (cf. Ladner Citation2014) – Norna recruiters often withheld such information. When I enquired about this, I was told that research participants have to be prevented from knowing who the client is in order to avoid bias. My interlocutors perceive that respondents risk failing to answer truthfully out of courtesy (cf. Gross and McGoey Citation2015).

In order to expedite a precise recruitment of participants while keeping the client secret, the recruiters at Norna have to ask relatively open questions in order not to give away too much about what they try to eliminate during recruitment screening. For instance, I had been introduced to a mixed qualitative/quantitative project for an insurance firm to help out in preparation for focus groups and the recruitment process was briefly explained during the meeting. Norna’s recruitment department had assessed participants from their client's customer register, by asking a series of questions over the phone. Potential participants are screened by being asked questions with several alternatives where some lead to elimination, or are asked open questions where only certain answers allow for selection. The screener aims to eliminate participants with the wrong profile (in this case pensioners and young people), and sometimes people who overly dislike the client firm (recruiters ask about attitudes towards a long list of companies as to not give away the client). The recruitment and assessment of respondents for qualitative market research thus requires a certain degree of secrecy. To Norna researchers, failure to keep certain details from respondents runs the risk of ending up with biased respondents and results.

Besides recruiting respondents, an important part of setting up a project involves scripting interview guides or questionnaires. My interlocutors see potential drawbacks of specifying the contents of an interview guide too rigidly in negotiating with the client. I have been told that it is common on the client’s part to want to maximise the number of questions. To do so may allow for pleasing numerous people within the client organisation as their particular questions have been included, or may be taken as a measure to cover all contingencies. However, this strategy causes concerns for the Norna researchers who see tendencies towards fatigue with respondents who are asked too many questions. Even worse, the risk of qualitative interviews or focus groups running so long that all questions cannot not be answered before the session ends may leave the researchers short on answers for their clients.

The issue of the over-elaborate interview guide may be mitigated in a few different ways – for instance, by prioritising so that at least the questions deemed centrally important by the researchers are asked early on in order to to avoid too much damage from time running out before all questions are discussed. Another tactic I observed is to use the discretion implied by the guide not being a script as previously suggested by the card company insight manager. This may not always be communicated to clients however, and during sessions with interview experts several of them readily acknowledged that there was more merit in a smoothly progressing interview where answers to all questions were arrived at than one where questions were posed verbatim. This possibility for leaving questions out creates room for qualitative researchers asking questions that they feel are better for producing answers to the questions put forward by the client. They sometimes do this without making evident the disconnection between clients’ demand for particular questions and their demand for precise answers. Further, clients are not always kept in the loop about the extent to which researchers adjust the scripts. Maintaining this distance allows the researchers some flexibility, while adhering to the statures of the client’s project specifications.

Stage 3: fieldwork

The formative results of market research are to be generated during fieldwork. During the fieldwork stage, the project manager oversees the compilation of data using methods such as quantitative surveys, focus groups, qualitative interviews, etc. Researchers may be in close contact with operatives within the firm who handle coding quantitative surveys, or they may directly interact with respondents through interviews and focus groups. Resulting materials (transcripts, data-sets, figures, etc.) are then to be processed to become informative in the later stages of analysis and reporting.

Contacts with clients in fieldwork sometimes pose challenges that lead to limiting of knowledge. During the active-wear project the client’s involvement in research came to be discussed. The project used an online platform: a private forum with subsections and individual logins for respondents to participate in a sort of asynchronous focus group over the course of a few days. After a while I learned that not only the researchers and respondents had access to the platform but the client too. I asked Eric if this would pose problems with clients jumping to assumptions based on particular details. His reply was that knowledgeable clients could offer useful details but that less experienced clients could ‘get lost in peripheral things’ and that client representatives could request focus on ‘some token detail of theirs.’ Eric’s account suggests how the making of knowledge about consumers may be both helped and impeded by what the client knows. Clients who have insight into the day-to-day progression of the online platform used in the project may offer the researchers helpful suggestions. They can also be a hindrance if they come to focus on details that are not useful in Norna’s mission to inform them.

Just as in recruitment, the name of the commissioning client is often withheld during fieldwork. Either it is kept from respondents for part of the session in order to gauge respondents without risk of bias (cf. Muniesa and Trébuchet-Breitwiller Citation2010) or, alternatively, the client remains secret throughout the interview, survey or focus group. In the case of the active-wear project for instance, the first few steps of questions and answers were executed with respondents who were not informed about who the client was. (In the projects that I observed, the client would be kept secret for as long as was practically possible.) Expert in qualitative methods Edward expressed related concerns over bias among respondents, mentioning that they may become shy or deferent to each other based on details about work status, education, etc. For instance, the presence of a senior academic or medic was thought to be able to sway a group. According to Edward, this too prompted suppressing certain personal details about the respondents, for the sake of an ‘equal discussion.’ A certain degree of anonymity is regarded as conductive to producing unbiased results.

Stage 4: sorting and analysis

During sorting and analysis, the project outline designates tasks that involve organising and interpreting the materials that have been generated in the fieldwork stage. To a large extent, such treatment can be in the form of summarising quantitative results into graphs and figures, or sorting qualitative results from focus groups according to research goals. Interpretation plays a significant role, both in deciding what certain material indicates, but also in determining what is relevant for the client and what merely constitutes noise. The latter issue of mitigating noise is especially relevant for the compilation of materials into results, just as knowing the difference between signal and noise is a skill that Norna assumes in relation to their clients. Further, the decision of what is or is not noise depends on the goals of the study. In practice, such considerations also help sorting through what is worth communicating for the next presentation stage.

Eric tells me that separating ‘findings’ from ‘noise’ is an acquired skill. According to my interlocutors, the client who lacks the same know-how, is therefore best kept from certain findings as they lack the tools to discount irrelevant information. He explains this during an interview where he talks about the qualitative audience testing projects that he often undertakes:

Say that we’re doing testing of a TV-series and a lot of comments about it being boring emerges. If you haven’t worked in this line of business you may think that is the core finding. But if the brief is about how to communicate it […] I think that should be the goal, even if there is a lot of noise in the group about not liking it. (Excerpt from interview, emphasis in transcript. Author’s translation.)

Stage 5: presentation

The last stage involves compiling and presenting materials as results to the client. Presentations are typically realised by both a live talk, supported by a PowerPoint presentation, as well as a report (a more elaborate version of the same PowerPoint document). Although Norna documents tend to describe this stage as the transfer of what was decided in the previous analysis stage, considerations over what to omit are important in realising a sufficiently informed recipient here as well.

During the active-wear project’s last meeting where the team as a whole met up, discussion took place on how to plan for and finish compiling the presentation. After getting a report on how the online focus groups had been running, and hearing that they had produced very interesting and plentiful answers, the discussion turned to who on the team will present what. As the presentation was not yet finished, there was also some discussion as to who would finish the slides. Further, Alice who manages the client account called for as full attendance as possible from the project members. She was concerned that there would be a large group of client representatives and Norna ‘needs to be able to match that.’ Eric, the researcher who was undertaking the online focus group would also be responsible for handling the presentation of those results, despite his qualms about lack of understanding of the analytical model that has been used in designing the study. Further, it was important that Aida, the researcher who was first presented as adept at needs segmentation in sales meetings was going to present the segmentation model, instead of the specialist at Norna who had done the analysis. Researchers were tasked with presenting the expertise on which merit the project was sold, even if it involved some degree of obfuscation over who did what in the project.

Discussion in the active-wear meeting progressed to what the quantitative surveys, undertaken in multiple European countries, had yielded and how the reporting of these results could be balanced against the qualitative materials during the presentation. Alice, the account manager, stressed that it was important that the needs segmentation model that would be used at a later project with the client received enough attention. This is because it was important to communicate the firmness of the model and how it was ‘validated’ by recurrent use in previous research projects in order to encourage the clients to go ahead with the next step: a new project using the full segmentation model.

‘Do we dare to show where [active-wear company] is on the [need segmentation] map? What do we dare say?’

‘Descriptions are partly overlapping to me as an outsider. I am afraid that it is not very clear to me.’

‘I don’t want them to jump to conclusions from this material. There is a risk that they will then say “we know everything we need already”.’

‘Can we not describe the category in light of the different categories?’

‘We have been using it as a projective exercise and it is an indicator. But with this small group we have found that the results are varying.’

‘It will differ in a quant too.’

‘But less so, and that discussion I want to avoid in the presentation […] We will come back to questions about it [need segmentation]; here it has been used as a method to get beyond the functional, to get to emotional associations. At that stage, we should not go too far into the model. Or [need segmentation] analysis, but more that it is broad strokes.’ (Excerpt from fieldnotes. Author’s translation)

Understanding non-knowledge in market research

Norna’s market research practices are not only executing a plan to gather data and analysing it in a manner which produces information that is presented to clients. Rather, each stage of the process features work that limits what involved clients and/or respondents learn (see ). summarises the examples of limiting information given in the outline of Norna’s research process. In an effort to be symmetrical with knowledge and how it is meant to be provided by researchers, this table also specifies who are made the recipients of non-knowledge in each stage: keeping others from knowing certain things helps the successful formation and dissemination of useful knowledge.

Table 1. Stages of the Norna work process, with practices of limiting knowledge on the part of actors.

Studying the stages of Norna’s market research projects, while considering how this process involves shaping the non-knowledge of involved parties, shows market research featuring several forms of omitting or withholding information. Although research builds on practices of finding out, organising and explaining it also involves secrecy and engineered ignorance. Further, my interlocutors at Norna interpret their work in ways that suggest a one-way process of meeting what is not known with new knowledge (e.g. the Norna project process). However, this does not convey all the detail of undertaking research, nor all the considerations of Norna researchers. In order to continue this inquiry, my interlocutors’ understandings of how to limit knowledge to make knowledge will be assessed drawing on two things: first, the framing of secrets and the distribution aspect of non-knowledge; second, ignorance as a way for making certain understandings possible.

‘Very disadvantageous to us in that it becomes transparent’

One way of dealing with the limitation of information flow at Norna is to take note of those anthropological approaches that point to the distribution of knowledge as a social tool that constitutes people into particular relationships. Such a tactic looks to how unequal distribution of information also distributes influence and power. It helps to explain Norna researchers’ handling of information and secrecy as social action that limits information of ongoing research, in order to preserve a position of interpretive authority. Researchers seek to be intermediaries between clients and the market phenomena that they study (cf. Nilsson and Helgesson Citation2015).

A telling example of how knowledge and non-knowledge may be understood as distributed for the sake of social manoeuvring lies in the use of the term ‘transparency’ at Norna. Indeed, just as transparency has been derided as a problematic buzzword by social scientists (e.g. Strathern Citation2000), C&T researchers also regard the term as detrimental – albeit for different reasons. For example, Aaron, an account manager with a background in advertising, used ‘transparent’ when outlining the precariousness of a tight pricing model (cf. Hagberg and Kjellberg Citation2015), where too much knowledge gets in the way:

If you don’t become consultative yourself, then the client will point at you and ask ‘this is what we want, and you cost more than fifteen competitors. Why are you so expensive?’ […] It becomes difficult to charge. It makes for a very transparent price setting: How many hours, how many programmers’ hours, how many minutes. What’s the cost-per-minute? It is a pricing model which is very disadvantageous to us in that it becomes transparent and prices may be kept down. (Excerpt from interview. Author’s translation)

Cases where transparency is considered detrimental by enabling price pressure on the part of clients tie once again into the notion of distributing power relations through information. Knowledge might not equate to power, but its distribution is considered a factor in negotiations. Norna researchers care about limiting information to maintain room to move ‘behind the scenes’ (Goffman Citation1974), but also appear to be involved in making knowledge useful as much as making sure that useful knowledge is made. This brings the inquiry to consider how knowledge (and its limits) adds to cohesive understandings.

‘At times, there has been a little too much focus on what goes on’

My interlocutors at Norna see aspects of omitting information in relation to concerns over maintaining the space for manoeuvring during the research projects, particularly with regard to freedom to design and interpret studies conducted. In such cases, the freedom to manoeuvre has to do not only with giving room to do business. Rather, the limitation of what clients know is also epistemically motivated. Alice, who specialises in consumer research, expresses this ambivalent attitude to the withholding of information in discussing ‘black-box’ phenomena:

But I do remember that we spoke about … kind of … that one may think of qualitative methods a little bit like a black box. Once you had a project you went into your black box and then the client didn’t understand what you were up to and then you come back. And the client doesn’t know what has transpired. And it felt like the business said ‘now we’ve to open the black box’. This is way back – er … getting the client to understand and like participate … and you know really understand what goes on in there. And that’s all good and well. I on the other hand, I can feel that I would like to shut our research away again [laughs]. You don’t have to mind what happens in here or which tools or methods we use, because here are questions and here knowledge comes out. Sometimes – at times there has been a little too much focus on what goes on in […] the box. (Excerpt from interview. Author’s translation)

In Alice’s example, transparency as a negative is paired with another unusually loaded term: the ‘black box.’ Common in STS literature and other social science, the black box tends to denote something that is kept from scrutiny, to be taken ‘as is’ (cf. Latour Citation1987). In the case of the account manager at Norna, black-boxing is seen as useful for the researchers and even beneficial for the client as it allows researchers to do their job more freely, purportedly producing more useful results. The working of Norna’s branded methods products are less available to clients than custom solutions where the details have been reached through negotiation. Discussing this with Alex, he notes: ‘But then there are people who hate the part that is any kind of black box. And then you have to do something tailor made. And in those cases the really sharp analyses, they don’t really happen then.’

In response to my interest in client reports, Eric debriefed me after some of his client presentations. These conversations made room to ask about choice of what to communicate and what to leave out. It is important, he claims, to remove unnecessary details to ensure that clients do not get lost in the detail. After the active-wear company presentation, Eric came by to let me know that it went very well. First of all, he said:

It was good that we were prepared with a very simple pedagogic presentation. Also, since Pia went before me it gave me some time to remove a few slides that they would have jumped to conclusions from. (Excerpt from interview. Author’s translation)

Yes, sometimes you have to be assertive, really drive the agenda, not wait for them to let you switch slides […] It is easy to give people too many details to get lost in. Better to remove information so that they can focus on the important findings.

[Y]ou said that you had been able to remove some stuff. Live, kind of. That you were able to hide some slides and stuff.

Yes, exactly

How did you figure? What did you remove?

I thought like this: as there were a lot of … questions about details, like the first questions put to Pia were like ‘is that really the right exchange rate between Swedish Krona and Euro?’ And that was a meeting with executives present, and like important things were going on, so it felt like ‘ok, here it’s about being able to defend what you talk about, so maybe not to say too much about stuff that will give rise to questions that are not central’, So, I removed this … I had made this qualitative categorisation between protecting oneself against the external so to speak. Protecting your body, and on the other side a dimension about … multi-usage of garments, and specific garments for specific tasks. I thought it was ok when I made it, but in the light of what was there and how easy it was to provoke questions and ‘could it be like this or like that’ I decided that ‘no, I’ll omit that’.

Sure

And then I ran through these need segmentation-inspired slides […] really quickly – so – not even elaborating on these that were more ‘it could be like this, or like that’. And that was also because there were many of them, with a lot of words, and I felt like I was in the same boat as Pia [who had just previously had a difficult time explaining the quantitative survey] where I felt I had results that I could not explain if they put forward questions on it, like. (Excerpt from interview. Author’s translation)

Discussion

This inquiry has identified different practices and understandings of making non-knowledge. As shown throughout the work process at Norna, several different practices appear to limit what clients and respondents know in order to produce research material. As shown in researchers’ explanations, metaphors such as transparency and black-boxing indicate work to mitigate the spread of information. These manoeuvres constitute actors and their relations in order to produce compelling knowledge and relationships. In the case of seeing secrecy at work, Norna’s researchers’ reluctance to part with client information, or presenting already familiar faces as experts, manages social relationships with respondents and clients, respectively. The same is true in the active-wear project where researchers present a select amount of results from segmentation techniques to receiving clients. Such a strategy aims to entice clients to purchase a further study. The theme of epistemic cohesiveness becomes relevant when looking at further aspects, such as how Norna researchers consider transparency as a problem beyond the politics of price setting and wish for more daring solutions than those with which the client is already familiar.

The penchant for black-boxing at Norna furthers the tendency of obscuring that which risks being plain in order to bring clarity: keeping clients from too many details may be deemed necessary to ensure that they receive results in a manner which reduces noise, and allows clients to appreciate the relevant ‘signals’ (Lakoff Citation2002) of the market (c.f. Nilsson Citation2018a). When MacKenzie (Citation1990) and Collins (Citation1997) discuss the role of distance in understanding knowledge, they outline it in terms of remoteness from an imagined centre: the site where knowledge is being made. Distance and proximity in relation to this site is thought to impact how an actor understands or trusts scientific knowledge. The findings from this inquiry into market research suggest a situation where distance is not a given, but subject to active manipulation. At Norna the researchers strive to affect epistemic distance through managing what clients learn. Thinking with MacKenzie’s (Citation1990) observation of the certainty trough, it appears especially important to manage the client’s stay within the confines of certainty: too much or too little information will lead to misunderstandings, senseless ignorance or awareness that feeds clients’ uncertainty. Well-catered managing of knowledge and the limitation of insight that leads to doubt or misunderstanding puts the client in a sort of epistemic sweet spot.

Further, maintaining distance appears a concern in how respondents’ knowledge risks becoming spurious in the eyes of my interlocutors. In respondents, the intimacy of getting to know too much about clients or each other threatens the integrity of research. Reasons for limiting information on the part of respondents appear to veer close to those in experimental social sciences (Ladner Citation2014). Market research respondents are thought to become less reliable if knowledgeable about who is the recipient of study results. By not knowing who the client is, respondents are unable to skew their answers in a manner they think pleases the client. Lack of knowledge is thus thought to allow for the true attitudes of consumers and customers to be gleaned. At times, this demand for unspoilt respondents proves impractical, as respondents must sometimes be vetted to establish that they have appropriate experience of a given range of product or services, or in situations when focus group participants are to give their opinion about a client brand or company’s services. However, this engineered non-knowledge aims to keep respondents at arm’s length from mechanisms they may upset, while in appropriate proximity to be assessed.

Attention to manoeuvring vis-à-vis clients and respondents suggests another aspect of how market researchers attempt to manage the epistemic distance between respondents, clients and themselves. Market researchers are involved in handling and manipulating distances in order to maintain an intermediary position for themselves. This position features the role of expertise (Collins Citation1997), as well as privileged access to both respondents and clients (cf. Barth Citation1990). The role of the market researcher is to assess and analyse respondents on behalf of clients who are to be informed and ultimately helped by the results that researchers produce. Clients’ direct involvement in situations such as focus groups or encounters with respondents is thought to risk misunderstandings and may challenge the position of the market researcher as an authority on what is going on. Similarly, direct involvement of clients may lead to exposure to the respondents.

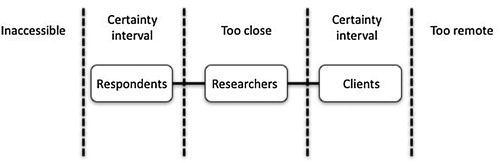

In order to show how market researchers are involved with managing their relationships through epistemic distance, their work can be illustrated as a relationship between actors (see ). Researchers maintain ties with both respondents and clients. In both cases, these connections are maintained not just through tightening relations. Rather, the researchers maintain a particular epistemic distance. Respondents are to be close enough to be assessed, but not close enough to get too familiar. The clients are to be kept in the right certainty interval where they are informed enough to feel confident in results, but not so close that they get overexposed to details. Further, market researchers maintain their middleman position by adjusting relations in a manner that does not put clients and respondents in direct proximity to each other. My interlocutors’ clients are both given details and kept ignorant as a way to foster understanding, need and trust in the services of researchers. Respondents on the other hand are often kept from the nature of clients in order to mitigate their perceived tendency to say what they think their audience wants to hear.

Figure 1. Relationship between researchers and actors across epistemic distance. Source: Author’s work

If making knowledge relies on making certain non-knowledge with certain actors at Norna, this is relevant in light of the linear process descriptions espoused, both within the particular firm and in the market research business more generally. Instead, certain forms of ignorance are maintained and devised for the successful move from setting up and studying people to the eventual presentation and information of clients.

Conclusion

The Norna case suggests how the managing of distances and maintaining relationships go together in undertaking a market research project. In general terms, the case features strategies to shape connections in two related modes: one is to make sure that market researchers are intermediaries – a necessary interpreting and executing agent in between the clients and the respondents. The other is keeping both groups ignorant about certain things in order to make knowledge possible. Collins’s note that distance brings enchantment (Collins Citation1997) is telling for the closing of knowledge gaps in market research. Such distance is neither given, nor static. Rather they are subject to manipulation by market researchers who want to do compelling research.

This inquiry suggests treating market research as an endeavour that encompasses both knowledge production and marketing practice. Rather than assuming the separation between client relations from research concerns, between the market and the social or cultural or the banishments of ignorance through facts, this article has discussed how market researchers address clients’ needs by shaping epistemic distance. In this, a different kind of spatiality is suggested. Research may tie worlds and people together, but it is not only a matter of closing gaps; it is also work that relies on sustaining certain distances and blind-spots.

Doing market research relies not only on improving on knowledge but also on limiting information in order to bolster respondent relationships, client reception and trust. Maintaining non-knowledge is not only part of the strategic play for client relationships and sales but also plays a part in epistemic practice. This dual nature of doing market research speaks to the tensions between the product of market research being a good that is to be bought and sold efficiently and knowledge that is meant to see use. Studies of research respondents or how clients receive market research reports, can provide perspective to what it means to address separation and the unknown by removal and omission. Further research into ideas and practices of producing market knowledge may provide greater detail into how social and knowledge concerns intermingle through the shaping of epistemic distance.

Acknowledgements

CF Helgesson, Lotta Björklund Larsen, Niklas Svensson, Anthony Kelly, members of the junior faculty writing group at the Department of Social Anthropology at Stockholm University and the Market Seminar at Stockholm School of Economics all offered helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. I would also like to thank Sergio Sismondo for encouraging feedback and the anonymous reviewers whose comments helped me to clarify my argument.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Johan Nilsson is an affiliated researcher at the Center for Market Studies, Stockholm School of Economics. His research interests include the anthropology of markets, the role of marketing is shaping markets, and how markets, knowledge and technology intertwine.

References

- Araujo, L., Finch, J., and Kjellberg, H., eds., 2010. Reconnecting marketing to markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barth, F, 1990. The guru and the conjurer: transactions in knowledge and the shaping of culture in Southeast Asia and Melanesia. Man, 25 (4), 640–653. doi: 10.2307/2803658

- Barth, F., et al., 2002. An anthropology of knowledge. Current Anthropology, 43 (1), 1–18. doi: 10.1086/324131

- Belk, R., Fischer, E., and Kozinets, R.V, 2012. Qualitative consumer and marketing research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Bjerrisgaard, S. M., and Kjeldgaard, D, 2013. How market research shapes market spatiality: a global governmentality perspective. Journal of Macromarketing, 33 (1), 29–40. doi: 10.1177/0276146712462891

- Callon, M., ed., 1998. The laws of the markets: edited by Michel Callon. London: Blackwell Publishers.

- Collins, H.M, 1997. Expertise: between the Scylla of certainty and the new age Charybdis. Accountability in Research, 5 (1–3), 127–135. doi: 10.1080/08989629708573904

- Davies, C.A., 2012. Reflexive ethnography: a guide to researching selves and others. London: Routledge.

- Diaz Ruiz, C. A., 2013. Assembling market representations. Marketing Theory, 13 (3), 245–261. doi: 10.1177/1470593113487744

- Goffman, E, 1974. Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper & Row.

- Gross, M., and McGoey, L, 2015. Routledge international handbook of ignorance studies. London: Routledge.

- Hagberg, J., and Kjellberg, H, 2015. How much is it? price representation practices in retail markets. Marketing Theory, 15 (2), 179–199. doi: 10.1177/1470593114545005

- Heiskanen, E, 2005. The performative nature of consumer research: consumers’ environmental awareness as an example. Journal of Consumer Policy, 28 (2), 179–201. doi: 10.1007/s10603-005-2272-5

- Helgesson, C. F., Lee, F., and Lindén, L, 2016. Valuations of experimental designs in proteomic biomarker experiments and traditional randomised controlled trials. Journal of Cultural Economy, 9 (2), 157–172. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2015.1108215

- High, C., Kelly, A., and Mair, J., eds., 2012. The anthropology of ignorance: an ethnographic approach. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kjellberg, H., and Helgesson, CF, 2007. On the nature of markets and their practices. Marketing Theory, 7 (2), 137–162. doi: 10.1177/1470593107076862

- Kotler, P., et al., 2016. Marketing management (3rd ed). New York: Pearson.

- Ladner, S, 2014. Practical ethnography: a guide to doing ethnography in the private sector. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Lakoff, A, 2002. The mousetrap. Molecular Interventions, 2 (2), 72. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.2.72

- Latour, B, 1987. Science in action: how to follow scientists and engineers through society. Cambridge, CA: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B, 1999. Pandora's hope: essays on the reality of science studies. Cambridge, CA: Harvard University Press.

- Law, J, 2004. After method: mess in social science research. London: Routledge.

- Lévi-Strauss, C, 1966. The savage mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lien, M.E, 2004. The virtual consumer: constructions of uncertainty in marketing discourse. In: C. Garsten, and M. Lindh de Montoya, eds. Market matters: exploring cultural processes in the global marketplace. Houndsmills, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 46–66.

- MacKenzie, D, 1990. Inventing accuracy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- MacKenzie, D., 2008. An engine, not a camera: how financial models shape markets. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Manderson, L., et al., 2015. On secrecy, disclosure, the public, and the private in anthropology. Current Anthropology, 56 (12), S183–S190. doi: 10.1086/683302

- Moisander, J., and Valtonen, A, 2006. Qualitative marketing research: a cultural Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Muniesa, F., and Trébuchet-Breitwiller, A.-S, 2010. Becoming a measuring instrument: an ethnography of perfume consumer testing. Journal of Cultural Economy, 3 (3), 321–337. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2010.506318

- Nilsson, J, 2018a. Producing consumers: market researchers’ selection and conception of focus group participants. Consumption Markets & Culture, 2018, 1–14.

- Nilsson, J., 2018b. Constructing consumer knowledge in market research. Doctoral Thesis. Linköping University Electronic Press, (Vol. 735).

- Nilsson, J, 2019. Know your customer: client captivation and the epistemics of market research. Marketing Theory, 19 (2), 149–168. doi: 10.1177/1470593118787577

- Nilsson, J., and Helgesson, C.-F, 2015. Epistemologies in the wild: local knowledge and the notion of Performativity. Journal of Marketing Management, 31 (1–2), 16–36. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2014.977332

- Pollock, N., and Williams, R., 2016. How industry analysts shape the digital future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Proctor, R., 2008. Agnotology: a missing term to describe the cultural production of ignorance (and its study). In: R. N. Proctor, and L. L. Schiebinger, eds. Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance, 1–33. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Proctor, R., and Schiebinger, L.L, 2008. Agnotology: the making and unmaking of ignorance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Rappert, B., Moyes, R., and Other, A. N, 2011. Statecrafting ignorance: strategies for managing burdens, secrecy and conflict. In: S. Maret, and J. Goldman, eds. Government secrecy. London: Emerald Group, 301–324.

- Räsänen, M., and Nyce, J.M, 2013. The raw is cooked data in intelligence practice. Science, Technology & Human Values, 38 (5), 655–677. doi: 10.1177/0162243913480049

- Rowley, J.E, 2007. The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW Hierarchy. Journal of Information Science, 33, 163–180. doi: 10.1177/0165551506070706

- Ruiz, C. D., and Holmlund, M, 2017. Actionable marketing knowledge: a close reading of representation, knowledge and action in market research. Industrial Marketing Management, 66, 172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.08.005

- Saldana, J, 2012. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Steiner, P, 2010. Gift-giving or market? Economists and the performation of organ commerce. Journal of Cultural Economy, 3 (2), 243–259. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2010.494374

- Strathern, M, 2000. The tyranny of transparency. British Educational Research Journal, 26 (3), 309–321. doi: 10.1080/713651562