ABSTRACT

This article develops an approach towards managerial expertise as a practice organized around and dependent on what I describe as drafting time. The empirical focus is on an employee satisfaction survey at a South Korean conglomerate where I conducted ethnographic research between 2014 and 2015. Departing from approaches that see drafts in service of organizational function or as a production-line model, the article describes how drafting time is a state of work in which claims to expertise, and claims against a lack of expertise, are worked out away from the judgment of others. I describe how high-level human resources managers within the conglomerate Sangdo fashioned themselves as internal consultants through the development of a sophisticated employment survey. When the claims of the survey did not work out as they expected, they were able to re-draft their internal roles vis-a-vis other managers. The article highlights how drafting time is one way for knowledge workers to craft their expertise, particularly through the assemblage of different kinds of genres where their expertise might be properly recognized.

KEYWORDS:

During my ethnographic research in 2015 on corporate office life in South Korea, the image of an angel and a devil briefly appeared, albeit in doodle form. I was attending a meeting with assistant manager Ji-soon, and team manager Jang from the human resources department of the Sangdo Group where I was conducting fieldwork as an intern and researcher. Ji-soon and Jang were discussing the analysis of an employee satisfaction survey. Jang had become preoccupied by a significant problem in the analysis of two relatively simple questions from the survey: ‘What are three things that motivate you to work?’ and ‘What are three things that demotivate you at work?’ Sangdo’s South Korean employees answered that ‘salary’ motivated them the most but also that ‘salary’ demotivated them the most. This particular problem presented a contradictory set of facts to the HR managers, confounding their hopes for a swift analysis that they could present to the chairman and to other managers in the group. In the month prior, members of the HR team together with me as an intern-researcher, had been attempting to analyze the results through conventional visual genres: charts, graphs, color-coded tables, and ranking lists. Each of these approaches did not satisfy the managers’ standards, as elements like ‘salary’ (as well as other items like ‘benefits’) illogically appeared in both lists, implying either the questions or the employees were mistaken.

At the meeting, Jang began to experiment with a new way of visualizing the results by doodling cartoons of an angel and a devil on a piece of paper. The angel and the devil stood for the positive and negative motivation factors associated with the question. In between them, he then sketched out a Roman-style temple. The temple represented the home of the ‘engagement score’, a composite number of twenty questions about satisfaction and engagement. Jang was searching for a way to logically link all the question categories together. As his doodle became more elaborate, he tried adding analytic labels around the angel and devil figures (like ‘positive behavior influence’) to clarify their roles, but no visualization could make up for the fact that the survey data presenting an incoherent set of facts. Eventually, Jang discarded the idea of an elaborate visualization for the questions and the survey altogether, and proposed simply showing the questions and results as simple lists. To the team, this signaled a failure to achieve what they had proposed months prior – a complex survey that would rival external, paid consulting companies. Yet the significant problems of the analysis (nor the doodle) were never openly shared outside of the HR team itself.

This article analyzes practices of drafting among contemporary knowledge workers. In theory, the HR managers were meeting to draft a single slide for a report that was part of a larger project known as the satisfaction survey. To look at the clean, final product they eventually made – an analysis report on the survey – would retrospectively give the impression that the managers launched the survey, collected responses from employees, tabulated results, and organized them into a narrative-like written report detailing how employees felt that year across Sangdo. However, to look at it from the actual practices during the time spent drafting the report presents a picture of analysis gone partially awry: the survey proposal promised different things, the report was supposed to be completed in one month instead of the actual four, the survey data itself appeared to not make coherent sense, and the managers were very concerned with how their superiors and others in the Sangdo group would perceive them via the final report.

Drafts and practices of drafting are ubiquitous features of contemporary knowledge work, in South Korea as elsewhere. Scholars have situated discussion of drafts within broader accounts of textual production in which they are one part of the assembly process of institutional knowledge or action.Footnote1 Drafts play a key role linking inchoate ideas or raw data into ‘final’, ‘approved’ or ‘clean’ versions. What constitutes a draft or a final version in practice is of course extremely varied: drafting may index qualities of roughness, incompletion or simply something that has not been approved; finalizing in turn may index consensus, decision-making, or mere temporal completion.Footnote2 Nevertheless, the process of bringing a document or project from a draft to a final version instantiates an institutional sequence or process of legitimizing knowledge. By rewording, black-boxing, gaining signatures, or making something ‘rock-solid’ (in Bourgoin and Muniesa’s Citation2016 account), institutionally validated texts can be produced.Footnote3 Such processes themselves can give shape to organizational structures and roles which revolves around the production and approval of texts or files (Latour and Woolgar Citation1986, Brenneis Citation1994, Harper Citation1998, cf. Mills Citation1951). Within such sequences of finalization, others have observed that the drafting stage thus becomes a space and time of creativity, fragility, and politics (Giraudeau Citation2008, Kaplan Citation2011, Bourgoin and Muniesa Citation2016). Annelise Riles (Citation1998, p. 390) has observed that even things like the selection of wording on a document can reflect an ‘infinite potential … of alternative possibilities out of which [a] text had been created.’ And Catherine Turco (Citation2016) has captured how at an American tech start-up, social drama unfolds around the collective drafting of company-internal wikis in which employees closely attuned to the who-wrote-what on page drafts.

Drafts and drafting have typically been imagined around the heightened attention given to editing text-level artifacts, such as tweaks to their wordings and visualizations. However, drafting plays a much broader role in organizational practices and can help clarify aspects of managerial expertise. First, acts of editing or reviewing drafts provide the basis for myriad other kinds of genred practices, like meetings, brainstorming events, and formal approvals. Second, physical drafts themselves exist as a complex of different semiotic qualities, the definition of which may differ across professional areas. Drafts must be recognized or labeled by actors who might disagree about what exactly makes something a draft or not. Lastly, drafting for many knowledge workers is itself a temporal frame that encompasses much of work life itself. In this sense, more than just a physical draft, drafting time is a period when certain claims are being tested and evaluated, different parties are consulted, errant files are hidden away, and a proper evidential trail is arranged to produce a proper final version. Seen as a temporal aspect, drafting is not just an ephemeral quality of an artifact, but a broader time frame that encompasses much of modern work itself. As Pierre Bourdieu noted, it is within temporal intervals that many acts of concealment take place and to ‘abolish the interval,’ he wrote, ‘is also to abolish the strategy’ (Citation1977, p. 6). Drawing on fieldwork among South Korean managers, this article focuses on how drafting time is a significant frame within which ‘genre work' takes place.

The theme of this special issue, ‘genre work,’ takes as its premise that practice-level genres (things like brainstorming meetings, PowerPoint reports, and post-it notes) may have conventional uses or pragmatic ends, but the assemblage, coordination, and sense-making across genres constitutes an important site of action. Actors across a wide variety of contemporary economic work contexts have been shown to keenly attune to the way meaning is organized across genre types, particularly as a matter of affirming aspects of their professional identity or organizational status. In some cases, genre work might reflect the way American job seekers must manage the differences between genres of their career biography like their resume and LinkedIn pages, which each have different terms for how to think about work and time (see Gershon, this issue). In other cases, genre work might reflect the way that in India, different genres of accounting for labor time become associated with culturally situated labor types. Even though they depend on ‘informal’ accounting genres (and their labor), construction managers go to lengths to keep their own genres of accounting separate from the laborers (see Sargent, this issue). In this sense, to the degree that certain genres can become loaded with higher-order meanings and cultural associations, sorting them out in practice can go beyond functional issues of simply getting work done.

In this light, I situate my analysis in a South Korean context where ‘expertise’ has become a marked trait for recognizing and distinguishing value in the knowledge economy. Where workers in twenty-first century South Korea have broadly been socialized to discourses around individual performance, annual reviews, and work-tracking metrics, recent attention has shifted towards individual actors as bearers of intangible and artful knowledge and expertise (see Park Citation2010, Kim Citation2018 [Citation2001]). This contrasts with values of the past in which managerial tenure, technical knowledge, or corporate loyalty might have been seen as the most salient points of distinction (see Han Citation2010). A key dimension of globally circulating ideas around experts is the artful performance where smartness can be rendered visible and locatable in the individual as others have shown elsewhere (Knoblauch Citation2008, Ho Citation2009, Chong Citation2015; see also Carr Citation2010). In South Korea, self-help books regularly narrate how to improve one’s performances, get recognized in the office, and develop ‘insight’ as a skill itself. Workers who are seen to be particularly good at making successful presentations might be described as a ‘god of presentations’ (balpyo-ui sin) or ‘god of reports’ (bogo-ui sin), turns-of-phrase to describe seemingly effortless and innate expertise.

How do images of expertise, genre work, and drafting time relate? For those within privileged spaces of employment, like large corporations, differentiating who has knowledge and expertise proves a murkier task than images of expertise would suggest. This is partly due to the complex topography of modern office work in South Korea: workers in large companies are socialized to work across a number of genres of documentation, like interoffice memos, proposal writing, and accounting and financial statements, while also becoming adept at presentations, collaborative work with others, and written and oral reporting to senior executives. It is also partly due to the way employees are conventionally distributed across stratified managerial ranks, located within small teams, and situated within complex organizational arrangements with divisions, parent companies, and subsidiaries. Genres of work intersect organizational relationships in complex ways and contribute to the difficulty of separating out or recognizing individuated expertise within office work. Constructing any kind of image of expertise (either at the individual or team level) requires significant genre work within and across projects. Because the performative stakes of individual projects can be high (or are perceived to be high), much of South Korean office work is organized around perfecting documents, planning their delivery, and receiving recognition from superiors (see Prentice Citation2019). Drafting time can literally describe the everyday experience of doing team-based work on drafting segments of project-based genres; it can also capture the way that claims to expertise can seem remarkably tenuous, as the story about the doodle indicated.

This article argues that drafting is a particular kind of organizational time that emerges in response to the uncertainty of managerial knowledge work. Considerable genre work – that is, the practice of coordinating across written artifacts and genres of interaction – happens within drafting time, not only where knowledge is mechanically ‘produced,’ but where errant ideas, mistaken analyses, confusing results, and changes of opinion might be managed as well.Footnote4 Drafting time can be understood as a kind of backstage within organizations where the ‘conditional authoritativeness’ (Brenneis Citation1994, p. 30) of expertise is worked out. This is because expertise is contingent on the continuous enactment of both recognized forms of satisfactory knowledge and the (personal or group) expertise that can be linked to such knowledge.Footnote5 By focusing on drafting time, then I aim to situate management not as an already-achieved apparatus of control and expertise, but as a field composed of specific actors whose individual epistemic claims are particularly fragile in practice (Bourgoin and Muniesa Citation2016; see O’Doherty and Ratner Citation2017, in this journal on the ‘break-up’ of management). This is true for iterations of consultant-like expertise based around short-term projects with ambitious goals (see Chong Citation2015; see also Graan in this special issue). It is also particularly relevant in a South Korean corporate context where individual managers and teams can be densely organized into ranks with others in large organizational environments where multiple managers may be attempting to demonstrate their own forms of expertise.

In what follows, I narrate drafting time around the Sangdo satisfaction survey. This was the project I as a researcher spent the most time on with the Sangdo HR team. It was also one of the few projects that allowed the HR team to have a particular angle of expertise within a complex and shifting organizational context (as I discuss in the next section). Though it constituted one ‘project,’ I highlight two different periods of drafting time where the pragmatic goals and genres involved were starkly different. I first discuss the development of a proposal when HR managers used drafting time to configure themselves as quasi-Western management consultants, revolving around the development of an internal proposal in which the image of the expert analysis could be tightly narrated. I then turn to when the team analyzed the survey data. At this time, HR managers reckoned with the fact that their grand plans for the survey in the proposal did not pan out. Managers re-adapted to a new set of genres that would articulate their relationship with others in the organization away from a consultant role. Moreover, they also concealed the fact that their original plans had, in fact, not worked out. While drafting time affords two very different kinds of organizational identities to take shape across various genres, I ultimately highlight how drafting time is a privilege not always extended to those who are granted less leeway to shape their own expertise in the first place.

Mediating new relationships at Sangdo

I conducted embedded research inside the Sangdo Group’s holding company in 2014 and 2015, formally working as an intern on the human resources team. That year’s employee survey was not the most important project the HR team would operate, compared to projects like updating performance and promotion methods, standardizing benefits, or instituting shared records systems across a large conglomerate of roughly a dozen subsidiaries and ten thousand employees.Footnote6 However, it was one of the only projects where the holding company’s HR team had a license to contact and gather data from employees across the conglomerate without having to ask permission from subsidiaries and their own human resources departments first. By virtue of carrying out the annual survey, the HR team was acting on behalf of the Sangdo Group chairman and owner-executives who would see all the results across the group, company-by-company. In theory, the survey would allow the headquarters to rank subsidiaries based on satisfaction levels and ask them to address specific problems within their workforces.Footnote7

The survey project was significant because the holding company, despite having a majority financial ownership over subsidiaries, did not have significant operational authority across the conglomerate. While technically the parent company to subsidiaries, the holding company of Sangdo had been created in the early 2000s as a vessel for transparent corporate governance. Compared to the half-century of history carried by each of the individual subsidiaries some of which managed their own international offices, the holding company for many years had only a handful of employees. In this sense, it had little legacy as a managerial hub and only a nominal claim to authority based on financial ownership. At the time I worked as an intern, the holding company was going through a hiring boom, in which new departments were created and new managers and executives were brought in from consulting and accounting firms, as well as more prestigious South Korean conglomerates. These managers were sociologically elite, coming from well-known universities or larger name-brand corporations where they had been climbed the management ladder before moving to Sangdo. Yet, despite a boost in prestige and at least the appearance of power, individual teams in the holding company, from HR to legal to strategy, had little operational power over subsidiaries. Subsidiaries maintained and invested in their own separate management systems and were sometimes skeptical of a new management hub that had only been around for a few years where few of the managers knew anything about the respective markets or labor contexts of individual subsidiaries.

In practice, the relationship between the holding company and subsidiaries was mediated by complex array of genres across areas of management. The legal team, for instance, could receive written appeals from subsidiaries about potential liabilities, and would issue formal written legal advice back. The performance management team, in charge of consulting on aspects of factory productivity, relied primarily on a monthly report that subsidiaries had to fill out and update with their latest sales and production figures. The HR department relied on formal memos, Excel-based templates to capture information about internal labor statistics, policy recommendation reports, as well as ERP-based software for personnel tracking, among others. Mediated by rather simple communication genres that required co-participation and input from the subsidiaries, the holding company's authority was often hampered by subsidiary personnel who would figuratively drag their feet, fill in forms incorrectly, or not fill them in at all.

In this context, the group-wide employee satisfaction survey – launched as a pop-up on the intranet for every employee in South Korea – was one of the few projects that connected the HR team to each white-collar (office-based) employee in each subsidiary directly. The managers in HR were concerned with improving the work cultures at Sangdo’s various subsidiaries, especially at offices or factories where employees were known or rumored to work long hours, endure hard-driving managers, and experience sub-par office conditions. Because holding company managers were largely new to the group and not lifelong members of Sangdo, they did not have a strong buy-in to what they perceived as an ‘older’ style of hierarchical management at local Sangdo offices. As highly credentialed managers, many saw lifelong Sangdo employees at the subsidiaries as provincial and outdated, unable to meet the demands of rapidly changing domestic and international steel business in which new expertise, not old-school thinking, was required. Reflecting broader imaginaries of the role of older managers in South Korea, HR managers imagined that the survey would capture the voices of young and junior employees in the subsidiaries who were being unfairly treated by older managers and executives whose behavior and leadership was from a different era.

The survey served as a basis for re-imagining and instantiating the knowledge hierarchy of the holding company within the conglomerate. Primarily, it was a mode of demonstrating the expert authority of the holding company and its ‘new’ managerial elite vis-à-vis the subsidiaries and their ‘old’ managers. It would do so by corralling the voices of thousands of subsidiary office workers, who (the new managers thought) would openly and honestly express their true feelings on the survey, thereby circumventing the power of their own managers. The questions they developed reflected an implicit critique of the South Korean workplace. Many of the forty questions on the survey implicitly focused on potentially inappropriate team and subordinate/manager relationships, as well as offered opportunities to share opinions and seek individual advancement. The survey would expand the geographic scope of the holding company’s expertise: it was originally planned to be written in Chinese and English, in addition to Korean. (Chinese and English were the two imagined lingua francas of the majority of Sangdo’s global workforce.)

Such managerial imaginaries were easy to envision at the top of a tall office tower, relatively detached from local factory life and overseas branches. They signaled the potential in the survey itself as a singular project that would bring about or entail a new participatory structure of expert-based management within the group. The survey as a form was imagined to be able to shift the relationships among the holding company, subsidiaries, and employees: by surveying the voices of employees directly, the holding company managers believed that subsidiary leaders would fall into an evidential trap in which they could not deny the honest opinion of their employees’ voices. In turn, they would have to follow the directives of the holding company managers who held the data, the analysis, and the expertise.

Time 1: drafting expertise

In a small meeting room in November 2014, three members of the holding company HR team and I had gathered to discuss a draft of the satisfaction survey. Prior to the meeting, assistant manager Ji-soon and I had brainstormed draft questions and question areas for the survey, and we were presenting them to Jang and assistant manager Min-sup for review. Ji-soon and I had divided questions into three areas: ‘My Job’ ‘My Sangdo’ and ‘My Company,’ each of which each contained five questions that would be averaged to form new statistical indices for each subsidiary.Footnote8 In the meeting, Team Manager Jang began suggesting new questions, including some as a joke, such as a fill in the blank: ‘Everyday I wanna ____my boss’ which he wrote out in English. He sardonically wrote ‘kill’ as one potential answer for employees to respond. At moments of more banality, he and Min-sup debated the merits of a 4-point scale versus a 5-point Likert scale, arguing that their boss preferred surveys with 5-point scales.

The first period of ‘drafting time’ reflected a period of free thinking in which different survey ideas and plans were discussed. At some moments, there were opportunities for norm-breaking creativity, such as when the HR employees entertained the idea of asking employees indirectly how late they stayed at work or how much they were forced to drink with their bosses, common reference points for complaints in South Korea. The team was looking to overhaul the entire survey structure and analysis, such as by adding new composite categories of analysis like ‘My Job.’ Previous iterations of the survey had been carried out before in 2007, 2009, 2012, and 2013, with different personnel in charge. According to Team Manager Jang, the previous year’s survey was ineffectual because, although it had accurate quantitative results, the results were practically useless as analytics. No one knew whether a ‘3.3’ average satisfaction rate was good or bad, or how much change was necessary to change; as a result, subsidiaries were not impelled to clean up their workplace cultures. The entire 2014 survey was rewritten, including renaming it from a ‘satisfaction survey’ (manjokdo seolmunjosa) to an ‘engagement survey’ (moripdo seolmunjosa).

Part of the work of marking their survey as distinct involved differentiating it from the surveys conducted by subsidiaries and managers past, while aligning it with the knowledge work of external consultants. This is in many ways a common South Korean playbook for differentiation: adopting global (particularly American) forms of business analysis and applying it as a best-practice benchmark to one’s local office where new instances of a traditional-modern divide can be invoked. The HR team referenced old consultant reports they had which showed how to create compelling analytic tokens (such as ‘drivers’ and ‘indices’) that could be used to convey important factoids to subsidiaries. They also looked at the American Society for Human Resources Management’s (SHRM) guidelines on employee surveys, downloading batches of questions and translating them into Korean (as all of the members of the team could read English documents). They also looked to extract ideas from the ‘Great Place to Work’ survey which had a local office in Seoul but came at a considerable cost as an outside consultant. Veteran managers like team manager Jang were skeptical of some of these methods and the ends they were put to. When showing me old reports, he would often scoff at the ways large consulting companies used arbitrary rubrics of satisfaction, backed up by statistical averages, to make bold claims about the dependent and independent factors affecting workplace satisfaction. In the end however, it was these kinds of genres and styles that the HR team most closely sought to resemble as they reverse-engineered their own survey.

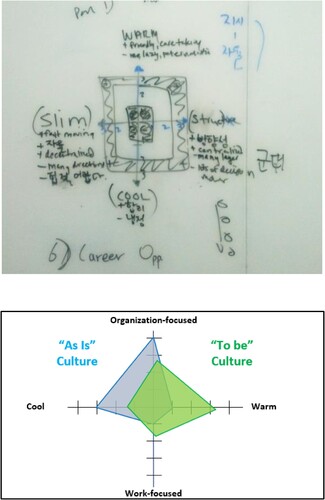

Assistant Manager Ji-soon and I drafted questions that could cover the breadth of diverse professional experiences across the Sangdo Group, working across a shared whiteboard, Excel spreadsheets, and draft proposals to Jang and Min-sup. Drafting time here represented a time of experimentation to test different methods, such as question formats, ‘as-is’ versus ‘to-be’ questions, and higher-level categorizations. One of the plans being drafted was to covertly organize the questions into categories that would form part of a two-axis model for mapping office culture by each office ( below). The team knew that advanced consulting reports used these kinds of models, but could not initially figure out which categories to divide the Sangdo workplace by. The team experimented with categorizing offices by whether they were ‘individualist’ or ‘collectivist’ in their attitudes, ‘work-centered’ or ‘organization-centered’ in their vision, well as ‘cool’ or ‘warm’ in their working relations.

Figure 1. Top: a mock-up of the spider chart with two axes used to classify corporate culture via satisfaction responses. Photograph taken by author. Bottom: the formalized spider chart, adapted from a PowerPoint Slide, with imagined graphic representation of internal cultural differences. HR managers had hoped to observe differences between how employees described their workplaces in the present (‘as is’) and how they hoped it might be in the future (‘to be’). Translated by the author.

In the design of the proposal, the team incorporated higher-level forms of statistical analysis into the survey design, as these were seen to lend more scientific legitimacy in comparison to the analysis of subsidiaries (who merely tabulated results with no correlation). Unsure whether this would actually work, the managers nevertheless proposed a causality feature in the survey design that would aim to statistically prove certain elements of employee behavior. They did this by tying explicit statements about employee engagement to various behavioral questions. With the help of a statistician, they were aiming to prove certain behavioral facts about the Sangdo workforce not just in that year, but as a general theorem. In theory, this would be able to tell them, for instance, that employees who worked late might correlate to being dissatisfied or unengaged. Rather than focusing abstractly on raising satisfaction numbers, then, they would be able to identify the specific behavioral levers for other subsidiaries to address – essentially cementing their expertise for that year and beyond.

The drafts of survey questions and analytic models culminated in a December proposal to the HR team boss, Executive Cho. The proposal outlined with high degree of confidence all the new analytic possibilities that would accompany that year’s survey: causality, demographic breakdowns, team-by-team analysis, new ‘motivator’ questions, and the ability to analyze subsidiary cultures. These promises were reinforced with visual sub-genres redolent of management consulting: process charts, spider charts, timetables, and numeric charts that lent weight to the scope and scale of the survey and its epistemic ambitions before it launched. The proposal itself was administratively unnecessary – no one at the organization formally required it – but it served to anchor the legitimacy of the survey to their superiors, the chairman and other owner-executives of Sangdo.

In the first instance of drafting time I’ve discussed, the team focused mostly on a narrow set of genres – survey questions and a survey proposal – through which they could both imagine and demonstrate the promise of their expertise. Both written documents underwent considerable drafting, as each member of the HR team reviewed the questions, fixed wordings, and offered ideas about the higher order labels. For the proposal, the HR team did not explicitly say they would be completing a consulting-like project, but nevertheless drew on a range of visual genres familiar to consulting that superiors, like their executive, owner-executives and the chairman, would recognize. Drafting time here operated as a relatively free space within the team to draft and craft their expertise on their own time and their own terms.

Time 2: re-thinking expertise

The engagement survey launched just before the new year via the conglomerate’s shared intranet with a neutral description and request for employees to anonymously share their opinions on the year prior. It contained no mention of broader plans or analysis and only minimal mention that it was conducted by the holding company. When the data was returned in early January, early signs indicated that it was a success, with more than a thousand employees responding. It was expected that the final reports to the chairman and subsidiaries would have been wrapped up by February. However, analysis stretched into April, with multiple drafts of final analysis reports repeatedly developed, discarded, and revised. The HR team was stuck analyzing what were supposed to be straightforward survey results, as a number of problems beset them.

In January, a report by the statistician hired to do regression analysis on the causal relationship between behavioral questions and satisfaction indices found margins of error of up to forty percent, making the paid consultation practically unusable. In late February, the tabulation of all the responses had to be recalculated as it was discovered that some factory workers had erroneously taken the survey meant only for office workers. (No one anticipated that they had access to computers). Following that, the team found out that one office that was presumed to have the lowest engagement turned in the highest engagement of any office that year (over ninety percent). The motivation questions, which would prompt the drawing of the angel and devil, came back with almost identical results – in which employees were motivated and demotivated by the same things. Most importantly, the responses to questions about employee behavior, meant to provide a foundation not only for an expert survey but a new model of internal-cultural analysis, came back with ambiguous results. This rendered the second-order analyses of the survey practically useless. To admit that the survey did not deliver on its quasi-scientific promises would admit that the survey had not succeeded, along with the team’s expertise. As no one outside the HR team was aware of the broader plans for the survey beyond the chairman and some high-level executives, the team went through drafts and drafts of analysis reports to resolve these problems – reinventing the survey and themselves after the fact.

During the proposal stage, the HR team had relative freedom over its own positioning as an expert with the promise of evidence. The necessity of presenting an appropriate evidential chain, from data to analysis, forestalled efforts at performing expert consultancy. Like other forms of expertise, managerial expertise draws on complex genres and linguistic registers unavailable to or different from laypersons (Goodwin Citation1994, Carr Citation2010). But, managerial expertise must rely on the proper presentation of evidence to base its claims, not unlike evidence-based scientific practice (Kuipers Citation2013). As efforts to marshal appropriate evidence became difficult, the managers re-drafted themselves, so to speak, to operate as collaborators with subsidiaries, rather than as managerial superiors. The second instance of drafting time afforded this new identity, in part by relying on a different sets of genres – data sheets, analysis reports, collaborative meetings, action reports, and even doodles – that could be coordinated and assembled together.

Early in the analysis, the team thought it might discover the holy grail of managerial phenomena, besting both the paid HR consultants who charged hundreds of thousands of dollars and outstripping the basic tabulations of subsidiaries, by locating a causal certainty around behavior and satisfaction rates. When the statistician’s report came back with the correlational analysis, it noted that there was a correlation between positive behaviors and high engagement rates at the aggregate level (across a thousand responses). However, for each individual subsidiary (whose samples ranged from a dozen to hundreds of workers), the margin of error ranged from five to forty percent. What were considered fuzzy but acceptable assessments of uncertainty to a statistician, to the managers was evidentially unusable because the numbers lacked the precision normally expected for tabulated results (e.g. a ‘93.4 positive satisfaction rate’).

Even basic tabulated results proved difficult. The team could not conceptualize how to make logical connections between the motivation/demotivation questions they themselves had designed. Team Manager Jang and I would go on daily smoking breaks (certainly one aspect of genre work) and discuss ways of working out the problem. With no analytic solution, the managers adopted an approach of simply reporting the answers as they were, with greater degrees of demographic specificity (by work category, by office location, by age and so on). They would let the subsidiary managers interpret what the answers meant.

A crowning piece of the survey was to be the new organizational analysis to typify organizational culture by behavioral descriptions (‘as-is’) and preferences (‘to-be’). Based on a set of twelve questions about their individual and team behaviors, the analysis comprised four categories that would classify offices, teams, and even age groups into recognizable types (seen in above). Accountants in the Busan office might be work-centered and cool (meaning they were not so focused on the social relations of their colleagues), whereas lawyers in Seoul might be more organization-centered and warm, suggesting they were desiring of a collaborative team environment. The HR managers imagined these would yield fundamental and observable cultural differences across teams, regions, and age levels. The results pointed almost entirely to uniform responses across all employees who curiously described themselves as ‘work-centered’ and ‘warm.’ That is, they desired both individual recognition and reward, and sought collaborative working relations, which HR managers thought would be mutually exclusive values. The survey revealed little of the analytic potential the HR team had hoped would result from their attempts at classifying culture (As Chong [Citation2015, p. 326] notes, Western consultants’ fascination with ‘culture’ has always focused on ways of defining culture as a variable to be controlled, even in light of evident failures to actually control or delimit it). While reporting these culture numbers would be ‘accurate,’ they would ultimately suggest that all Sangdo workers were essentially the same (or more likely, that they responded the same). The HR team decided to ultimately remove any mention of spider charts or cultural analysis altogether and simply reported answers to the twelve questions in that section.

One of the most surprising results of the survey were answers from employees at Sangdo South, one of the largest subsidiaries in the group. Sangdo South was believed by those in the holding company to have one of the most ‘militaristic’ (gundaesik) office cultures of the whole group (in part due to the company’s regional origins near a military base, its involvement in the domestic automobile industry, and the fact that ninety percent of its workforce was male). At the holding company, managers assumed they would have had many complaints. However, that company reported the highest engagement rates in the entire group. Some HR members believed that their managers might have influenced employee responses, giving them a secret nod to answer well while others thought it was because they had internalized a pro-corporate mindset. (Indeed, I had heard an account that mentioning one’s true opinion on something like an ‘anonymous’ survey was one method that the Korean military used to identify potentially problematic soldiers.) For the holding company managers, however, they found themselves in their own kind of evidential trap – there was no way to de-legitimize the voices of those employees via the data, unless they were to accuse the group’s most engaged employees of being insincere and secretly less happy than they reported. The holding company’s attempt to leverage the voices of supposedly oppressed employees to use against their managers was thwarted by employees themselves.

After abandoning other forms of analysis through multiple iterations of PowerPoint slides, the team settled on a visually stylish way to depict the information on PowerPoint. This style presented the survey responses for each company individually, and made no mention of any higher-order analyses and categorizations that had been promised in the internal proposal. In this sense, the team relied on a more simplified set of visual genres. The team spent multiple weeks tweaking the visual layouts of slides, the color gradients, the sizes and proportions of graphics, redoing every slide for every company. Perfecting the visual style and layout through graphics would compensate for a failure to develop any kind of broader organizational analysis. These final reports were developed in May, three months after they were originally promised. The team ended up hiring a printing company to bind a physical book of all the reports with a glossy cover to give to the Sangdo Chairman and its highest executive for their own private viewings.

After delivering reports to the chairman, Team Manager Jang scheduled meetings with each HR team manager to walk through the data for their own organization and highlight any specific issues that stood out. From the perspective of organizational hierarchy, the expert managers in the holding company were rendered (in their view) as equals to their counterparts in subsidiaries because of a lack of compelling insight to force their hand; they were merely transmitting numbers without interpretation. Ultimately, the subsidiaries could adapt their own data and decide how to use it. In one case that I was aware of, the HR department at ‘Sangdo First,’ another large subsidiary actually used the data to bolster its own expertise among its workforce. I observed in one visit how they re-drew the carefully constructed graphs from the holding company and added them to their own internal survey reports. The HR team manager from Sangdo First even used the survey results as an occasion to hold a focus group in June among managers at a regional office. At the focus group, he asked questions, listened, and discussed workplace problems. At no point did the manager acknowledge the role of the holding company in occasioning the event, nor did he report back to them his findings.

While the final versions of the survey reports were one way of concluding the analysis, ‘drafting time’ in some variety continued even after. After the meetings, the HR team decided to create ‘action plan’ templates in which each subsidiary had to identify key issues raised in their survey results and develop specific plans to resolve them. A junior employee Ki-ho and I were tasked with developing a new template for the action plans from scratch in a matter of a few days to distribute to each subsidiary. The results of the templates would be sent directly to the chairman to monitor their progress over the course of the year. As I finished my own research, I eventually lost access to any documents or internal information, so I could not see how things played out with the action plans. Nevertheless, from my involvement with the team I knew that such a format was largely how relations between the holding company and subsidiaries had been enacted before: the holding company created templates which the subsidiaries had to fill out and send up so that the holding company could compile them into reports for the chairman. Thus, after investing six months into developing and analyzing a survey that might transform them into consultant-like experts with an epistemic advantage over its subsidiaries and in the eyes of the chairman, the HR team ended up, at least from the point of view of how their relationships were mediated by certain genres of management, in the same position they had been before.Footnote9

From the perspective of the Sangdo Group as an organization, the survey actually raised some unique and fundamental workplace issues that employees across the subsidiaries were concerned about. The holding company managers reported them in a neutral way without exaggerating or tweaking their results and at least some of the subsidiaries pursued some of the structural reasons that lay behind the responses. The survey nevertheless felt like a failure precisely because it did not bring about a new state of affairs within the group. The fact that it avoided serious consequences to their broader position in the corporate hierarchy or individual positions is worth noting. By both drafting a promising survey and completely re-drafting a new style of analysis, the managers escaped judgments on their own potentially equivocating expertise. This is not to suggest that they had no expertise or were incompetent as managers, but it is to point out that drafting time afforded them the organizational cover to experiment with different kinds of genre work that underlaid the superficial genre of the ‘survey’ project. It is with some irony that they did so precisely via the survey which was meant to classify the managerial practices of others by appealing directly to the hearts and minds of junior employees in order to make fixed and stable judgments about their behaviors.

Conclusion

This article has discussed how important aspects of genre work are instantiated in time. As outlined in this special issue, genre work constitutes practices of attuning and coordinating across different genres. If genre work is indeed a kind of activity that actors engage in whether in the labor market or within organizational spaces, it must be situated within particular spaces and times. I have described one particular instance of this, drafting time, as a temporal frame that managers at a South Korean conglomerate relied on to craft their own images in the face of new organizational dynamics. I have described how HR managers at the Sangdo holding company both crafted themselves as experts as well as skirted claims they were not experts to avoid the scrutiny of those outside their team. Drafting time is one way of both preparing for and staving off organizational demands for concrete knowledge claims.

In contemporary South Korea, broader shifts to a knowledge economy have not only valorized insight and expertise, but also elevated the performance of expertise, in the form of ‘killer’ (ggeutnaejuneun) presentations. Drafting time, then, is a naturally corollary to such (final) performance-driven contexts, where actors spend considerable time on managing individual presentations across different genres. Ideologically, singular presentations are often foregrounded as ‘concrete’ instantiations of this expertise, but in organizational contexts, projects are often distributed across many different artifacts and interactions (data sheets, analysis documents, planning meetings, authorization documents, and others) that require significant time to coordinate.

An earlier generation of organizational theory aimed to elevate the role that genre types played in organizations, in part because the diversity of both office materiality and communication genres had been overlooked in conventional organizational theory. By framing genres as part of an organizational ‘order’ (Yates and Orlikowski Citation1992), organizational communication ‘systems’ (Bazerman Citation1994), as parts of ‘ecologies’ (Spinuzzi and Zachry Citation2000) or things that have ‘constitutions’ (Ashcraft et al. Citation2009), these conceptual approaches have drawn on both material and natural metaphors to elevate communication or documentary genres as the locus of ‘constructive’ or ‘structuring’ action in organizations.Footnote10 There is certainly nothing wrong with wanting to highlight how practices contribute to mediating organizational life (especially against purely behaviorist, cultural, or economic models). However, focusing on the ‘concrete’ qualities of genre artifacts can elide the ways that many drafts exist in states of high uncertainty where what is being built is never clear or guaranteed. I would suggest that drafts and drafting time have escaped theorization partly because failed or partially complete genre tokens complicate accounts of their (lack of) pragmatic action or structuring force in organizations. Projects that are never complete or documents that are never finalized might appear to undermine the role of genres themselves as a site of important action. Focusing on drafts then might risk revealing that organizations, teams, or management are as much about dysfunction as they are about proper function.

A focus on drafting is one way of excavating the ‘black boxes’ of managerial projects to see how they are messy hybrids full of competing and divergent epistemic claims. This is especially important for zones that are increasingly inaccessible to the public and to researchers (like high-level white-collar offices) where genres like public relations statements or annual reports are encountered only in their ‘final’ sanitized versions. This has led many to trace the ‘inscription devices’ (Latour and Woolgar Citation1986) that make up the black boxes of modernist institutions like science, government, and business organizations. Conventionally, artifacts like drafts are relevant in this process, including the wide variety of things explicitly labeled as ‘drafts’ and those implicitly part of the drafting process (errant notes, discussions, and the like). This article has also suggested that it is useful to consider drafting as a broader temporal frame that goes beyond physical artifacts per se as the locus of attention and includes other genres of interaction where crucial genre work takes place. Managerial work might be nominally organized around a single genre (like a survey) but in practice comprises multiple sub-genres of documentation and interaction, many of which leave no trace of their activity, draft or otherwise.

C. Wright Mills once depicted mid-century American offices as akin to factories for documents: ‘Each office within the skyscraper,’ he wrote, ‘is a segment of the enormous file, a part of the symbol factory that produces the billion slips of paper that gear modern society into its daily shape’ (Mills Citation1951, p. 189; cited in Lowe Citation1984, p. 137). While physical documents have been on the wane in the face of electronic documentation, Mills might not be surprised to see that modern organizations the world over still operate as document (or perhaps slide) factories, producing and storing documentation on a massive scale. But Mills had a functionalist understanding of the relationship of file-work to broader corporate power. This article’s perspective inside a South Korean organization suggests that strictly from the point of organizational function or knowledge production, much genre work is rather superfluous. That is, measuring employee sentiment through a survey might not need eight iterations to tweak wording or special statistical methods used as a form of differentiation. However, seen from the point of view of actors whose professional identities or organizational statuses are tied up in such projects then the stakes are quite different. As managerial expertise is staked to the successes and failures of organizational projects and the genres that compose them, drafting or even over-drafting might not just demand necessary techniques for perfection of certain artifacts, but time to work across genres and the composite impression they ‘give off’ to others across different points of interaction. A focus on drafting time reflects the broader idea that drafting workplace identities through genre work is itself an ongoing project with no concrete end, or final version.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael M. Prentice

Michael Prentice is a lecturer in Korean Studies at the University of Sheffield. He is the author of Supercorporate: Distinction and Participation in Post-Hierarchy South Korea (Stanford 2022). His research focuses on the intersection of management culture, genres of communication, and narratives of change in South Korea.

Notes

1 The fact that drafts prove difficult to discuss partly reflects Foucault’s (Citation1998 [Citation1969]) notion of the ‘author function’ by which the heterogeneity of real discourse is narrowed down or made sense of by locating an authorial persona. Drafts only make sense in relation to the final texts they ‘explain.’ Pointedly, Derrida (Citation2005, p. 29) wrote in his memoir, Paper Machine, ‘Some particular draft that was prepared or printed on some particular software, or some particular disk that stores a stage of a work in progress—these are the kinds of things that will be fetishized in the future.’ See also Hélène Mialet (Citation2012, pp. 145–146) on the way Stephen Hawking’s possessions were archived and catalogued after his death as relics of or clues to his genius.

2 Not all institutions operate via a model of a drafts and final versions; Garfinkel (Citation1967) noted that hospital nurses store written documents under a logic of seeing files as singular sites of ongoing record-keeping rather than temporally-punctuated moments of finalization. See also Hull (Citation2003) on the ongoing circulation of files and Dent (Citation2013) on ‘filtering’ as two very different bureaucratic-administrative techniques.

3 Equivalents of what I address here as ‘document drafts’ have nevertheless had significant impacts in other fields, namely anthropology and folklore studies, in which the imagination of the ‘complete’ or ‘original’ myth has long been dispelled. Myths, as well other kinds of traditional narratives do not have core versions with local or individual variants; rather, core versions of myths were themselves a modernist construction. Today, scholars in these fields attune to processes of ‘entextualization’ (Briggs and Bauman Citation1992) by which contextual features are removed to create an image of a ‘text,’ free of the contingency of actual situated performances (see also Briggs and Bauman Citation1999).

4 Some scholarly accounts have captured how office workers or consultants attune to the risks of actually finalizing drafts. These have been colorfully described as ‘ghost sliding’ (Nils Fonstad (Citation2003, cited in Yates & Orlikowski Citation2007), ‘orphaned drafts’ (Yates and Orlikowski Citation2002, p. 24), or ‘Swiss Cheese editions’ (Orlikowski and Yates Citation1994, p. 563).

5 Drafting time is not as expressive a term as Donald Roy’s (Citation1959) account of ‘banana time’ or ‘peach time’ where workers marked out there own shopfloor resistance through an expressive frame. Precisely because the messiness of drafting time is not meant to be captured, it is not necessarily a pronounced or nominally marked time of office life in South Korea.

6 I have adjusted numbers that make direct reference to the conglomerate as part of the anonymization process.

7 This is not unlike other surveys, which appear as a vehicle for numerical democracy, but are used to rank members. In his ethnography of complaint at a British bank, Jon Weeks (Citation2004, pp. 114–119) described how satisfaction surveys were used to create new forms of competition within segments of a large bank. In the UK, the annual National Student Survey, or NSS, given out to final-year undergraduates across degrees and universities, works in similar ways. It creates ‘league tables’ (rankings) between universities and programs along finite degrees of distinction along ‘quality assurance,’ based entirely on student feedback in ways that is administered from above and meant to put pressure on university and department administrators. See Sabri (Citation2013) for a description of the way NSS results circulate as ‘fact-totems’ inside universities and Law (Citation2009) for critique of citizen surveys in the EU.

8 ‘Sangdo Group’ is the pseudonym of a conglomerate which has multiple subsidiaries which each act as employees’ primary employer. One may feel to be as much member of a Sangdo subsidiary, such as Sangdo First, Sangdo Max, or Sangdo Net, as a member of the wider Sangdo group.

9 When I paid a return visit to Sangdo in 2016, a new HR manager recounted how he had updated the survey once again, grounding it more in formal psychology research standards, rather than consulting language, to legitimize the survey results.

10 In this sense, this body of scholarship also reflects a core tendency in ethnomethodology to see communication as a technical process or machine which is subject to ‘breakdown’ and ‘repair, as Paul Manning (Citation2008, p. 113) has observed.

References

- Ashcraft, Karen Lee, Kuhn, Timothy R, and Cooren, François, 2009. 1 Constitutional amendments: “materializing” organizational communication. Academy of Management Annals, 3 (1), 1–64.

- Bazerman, Charles, 1994. Systems of genres and the enactment of social intentions. In: Aviva Freedman, and Peter Medway, eds. Genre and the new rhetoric. Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis, 67–85.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourgoin, Alaric, and Muniesa, Fabian, 2016. Building a rock-solid slide: management consulting, PowerPoint, and the craft of signification. Management Communication Quarterly, 30 (3), 390–410.

- Brenneis, Donald, 1994. Discourse and discipline at the National Research Council: a bureaucratic Bildungsroman. Cultural Anthropology, 9 (1), 23–36.

- Briggs, Charles, and Bauman, Richard, 1992. Genre, intertextuality, and social power. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 2 (2), 131–172.

- Briggs, Charles, and Bauman, Richard, 1999. “The foundation of all future researches”: Franz Boas, George Hunt, native american texts, and the construction of modernity. American Quarterly, 51 (3), 479–528.

- Carr, E. Summerson, 2010. Enactments of expertise. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39 (1), 17–32.

- Chong, Kimberly, 2015. Producing “global” corporate subjects in post-Mao China: management consultancy, culture and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Anthropology, 4 (2), 320–341.

- Dent, Alexander S., 2013. Intellectual property in practice: filtering testimony at the United States trade representative. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 23 (2), E48–E65.

- Derrida, Jacques, 2005. Paper machine. Translated by Rachel Bowlby. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Fonstad, N. O., 2003. The roles of technology in improvising. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Foucault, Michel, 1998 [1969]. What is an author? In: James D. Faubion, ed. Aesthetics, method, and epistemology. New York: The New Press, 205–222.

- Garfinkel, Harold, 1967. Studies in ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Giraudeau, Martin, 2008. The drafts of strategy: opening up plans and their uses. Long Range Planning, 41 (3), 291–308.

- Goodwin, Charles, 1994. Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96 (3), 606–633.

- Han, Kyonghee, 2010. A crisis of identity: the Kwa-hak-ki-sul-ja (scientist–engineer) in contemporary Korea. Engineering Studies, 2 (2), 125–147.

- Harper, Richard, 1998. Inside the IMF: an ethnography of documents, technology, and organisational action. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Ho, Karen Z., 2009. Liquidated: an ethnography of Wall Street. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hull, Matthew, 2003. The file: agency, authority, and autography in an Islamabad bureaucracy. Language & Communication, 23 (3), 287–314.

- Kaplan, Sarah, 2011. Strategy and PowerPoint: an inquiry into the epistemic culture and machinery of strategy making. Organization Science, 22 (2), 320–346.

- Kim, Hyun Mee, 2018 [2001]. Work experience and identity of skilled male workers following the economic crisis. Korean Anthropology Review, 2, 141–163.

- Knoblauch, Hubert, 2008. The performance of knowledge: pointing and knowledge in powerpoint presentations. Cultural Sociology, 2 (1), 75–97.

- Kuipers, Joel C., 2013. Evidence and authority in ethnographic and linguistic perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 399–413.

- Latour, Bruno, and Woolgar, Steve, 1986. Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Law, John, 2009. Seeing like a survey. Cultural Sociology, 3 (2), 239–256.

- Lowe, Graham S., 1984. “The enormous file”: the evolution of the modern office in early twentieth-century Canada. Archivaria, 19, 137–151.

- Manning, Paul, 2008. Barista rants about stupid customers at Starbucks: what imaginary conversations can teach us about real ones. Language & Communication, 28 (2), 101–126.

- Mialet, Hélène, 2012. Hawking incorporated: Stephen Hawking and the anthropology of the knowing subject. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mills, C. Wright, 1951. White collar: the American middle classes. New York: Oxford University Press.

- O’Doherty, Damian, and Ratner, Helene, 2017. The break-up of management: critique inside-out. Journal of Cultural Economy, 10 (3), 231–236.

- Orlikowski, Wanda J., and Yates, JoAnne, 1994. Genre repertoire: the structuring of communicative practices in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39 (4), 541–574.

- Park, Joseph Sung-Yul, 2010. Images of “good English” in the Korean conservative press: three processes of interdiscursivity. Pragmatics and Society, 1 (2), 189–208.

- Prentice, Michael M., 2019. The powers in PowerPoint: embedded authorities, documentary tastes, and institutional (second) orders in corporate Korea. American Anthropologist, 121 (2), 350–362.

- Riles, Annelise, 1998. Infinity within the brackets. American Ethnologist, 25 (3), 378–398.

- Roy, Donald F., 1959. “Banana time”: job satisfaction and informal interaction. Human Organization, 18 (4), 158–168.

- Sabri, Duna, 2013. Student evaluations of teaching as ‘fact-totems’: the case of the UK National student survey. Sociological Research Online, 18 (4), 148–157.

- Spinuzzi, Clay, and Zachry, Mark, 2000. Genre ecologies: an open-system approach to understanding and constructing documentation. ACM Journal of Computer Documentation, 24 (3), 169–181.

- Turco, Catherine J., 2016. The conversational firm: rethinking bureaucracy in the age of social media. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Weeks, John, 2004. Unpopular culture: the ritual of complaint in a British bank. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Yates, JoAnne, and Orlikowski, Wanda J., 1992. Genres of organizational communication: a structurational approach to studying communication and media. The Academy of Management Review, 17 (2), 299–326.

- Yates, JoAnne, and Orlikowski, Wanda, 2002. Genre systems: structuring interaction through communicative norms. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 39 (1), 13–35.

- Yates, JoAnne, and Orlikowski, Wanda, 2007. The PowerPoint presentation and its corollaries: how genres shape communicative action in organizations. In: Mark Zachry and Charlotte Thralls, eds. Communicative practices in workplaces and the professions: Cultural perspectives on the regulation of discourse and organizations. Amityville, NY: Baywood, 67–92.