Abstract

The Azande of Ezo county, southern Sudan consider HIV/AIDS to be their worst health problem. Although there have been few confirmed cases, there is ongoing migration from neighbouring countries that are thought to have high prevalence. There are also more locally specific reasons for concern. Zande fears about HIV/AIDS relate to understandings of witchcraft. Witches, like HIV positive people, may look like everyone else, but are secretly killing those around them. Some individuals, who know they are HIV positive, demonstrate that they are moral persons by being open about it. They are active in providing information about the epidemic, and associate their activities with the Christian churches. Their efforts, and those of local religious and political leaders, have contributed to awareness about modes of transmission associated with sexual intercourse and contamination with infected blood. However, accepting such messages does not necessarily contradict witchcraft causality. Also, without knowing who are secretly positive, almost anyone is suspect. Advice about stopping sexual intercourse is viewed as untenable or worse, because sexuality and procreation are fundamental to life. A minority is enthusiastic about the use of condoms; but most people have had no personal experience of them and oppose their introduction. It is unclear why HIV/AIDS controls cannot be like those for other diseases, such as sleeping sickness. Support is expressed for testing facilities, and for clinical treatment. In addition, there are requests for all positive people to be publicly identified and concentrated in one place.

The Azande people of Ezo county, southern Sudan speak about HIV/AIDS with alarm. This paper explains their anxiety, delineating Zande understanding of HIV/AIDS in a context of notions and experience of illness, witchcraft and sexuality. It is mainly based on fieldwork carried out during June, 2006,Footnote1 but it also summarises available information about HIV/AIDS and other diseases, and draws on the earlier ethnographic literature about the Azande. Although the actual number of confirmed HIV/AIDS cases in Ezo is small, local perceptions about spiralling rates of infection are shared by district officials, public health workers and aid agencies. At present, the remoteness of the area and the unstable security situation has kept all interventions to a minimum. However, when that changes, responding to HIV/AIDS is likely to be prioritised. The paper ends by commenting on Zande views about control measures.

Methods used in the research were open-ended ethnographic interviews, focus group discussions, semi-structured interviews, participatory workshops, and class-based activities in schools. In addition, surveys using structured questions were carried out among a randomly selected group of 381 adults (roughly half male and half female, with an average age of about 30 years) living in Ezo, Naandi and Andari payams; and with 53 primary school students (70 per cent male, with an approximate average age of 14 years), from the senior classes of three schools in Ezo payam. In general, the answers to the structured questions tended to relate to notions of disease associated with health care services. It was in open-ended interviews that people were more prone to mention non-biomedical afflictions, such as magu (witchcraft) and ngua (magic). It was apparent that structured questioning about health was more associated with formal health services than less structured approaches. Also concerns relating to non-biomedical afflictions and causality do not necessarily exclude or contradict clinical interpretations. Therapy may require both consultations with local diviners and healers, as well as some form of medication from a pharmacy, shop or health centre.

Apart from the author, the research team included local medical officers, staff of World Vision Sudan, and seventeen locally recruited research assistants. It proved difficult to find female researchers, and only five members of the research team were female. This is a consequence of the much lower levels of formal education attained by women.Footnote2 The author has researched in southern Sudan and northern Uganda since the early 1980s, but had only briefly visited Western Equatoria before, and does not speak the Zande language. Like the four Kenyan is in the team, he needed to use translators. However, interviews carried out by the local researchers, including the surveys, were conducted in Zande and written up in Zande. Almost all quotations by respondents in the paper are translations from Zande, made by Zande-speakers in the research team. In a few instances, the author has corrected the grammar and spelling, while attempting to preserve the mode of expression.

Ezo County and HIV/AIDS

The traditional homeland of the Azande is divided by three countries, all of which have been seriously affected by wars and political upheavals: the Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR). Ezo county is located in Sudan's Western Equatoria at the point that the international borders meet. At Nabia Pai there is an artificial mound, erected in colonial times, which marks the point where the intersection occurs. On Saturday mornings it is the site of a busy market where people from neighbouring areas come to exchange commodities, to socialise, and to discuss such issues as the security situation. With the improved prospects for southern Sudan, following the ‘comprehensive peace agreement’, it is expected that Azande who have been living in the DRC and the CAR, as well as in Uganda, will return to their ancestral lands. It is also anticipated that other Azande whose ancestral lands are in the Francophone countries will join them. It is already happening on a small scale, and over 15,000 more migrants are expected in the next year or two. This pattern of interaction and migration is one reason why there are concerns about HIV/AIDS in Ezo county. It is thought that rates of infection in regions of neighbouring countries are relatively high. Could Ezo county be a vector of the disease into southern Sudan?

Ezo is a relatively new administrative county. Until the end of the 1990s, it formed part of Tambura county. It is divided into six payams (sub-counties), the most densely settled of which are Ezo and Yangiri, with populations of around 40,000 and 15,000 respectively.Footnote3 If the road is passable, it takes 6–7 hours to reach Yangiri from Ezo town. Naandi and Andiri payams both have estimated populations of around 11,000, and an estimated 9,000 people are scattered in the other two. Most of the populations of all the payams are Azande. There are also Avukaya, Baka and Mundu, but they are not a significant presence in the places in which research for this paper was carried out.

The county is located at the borders of the DRC and the CAR. Much of it is covered in lush woodland, and the United Nations Organization for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has reported that local farming meets 80 per cent of household food requirements.Footnote4 The presence of tsetse flies militates against pastoral production; although better off families sometimes keep a few goats or sheep. Hunting is an additional source of meat, and honey is also often available. The vicinity of international borders means that trade is an important aspect of the economy, and lively markets are linked to networks of exchange into Uganda, the neighbouring Francophone countries and other parts of Western Equatoria.

The county has a reported 43 primary schools with almost 20,000 students, including 8,400 girls.Footnote5 However, with the exception of one school in Ezo town, those schools visited in 2006 were very poorly equipped. Most did not have classrooms and attendance of girls was low in the senior classes. There is only one secondary school in the county, located in Ezo town.

Currently, there is a very low presence of international agencies. Until recently, Médicins sans Frontières-Spain was involved in sleeping sickness control. UNICEF and WHO continue to provide some assistance to health services, and there is a degree of external assistance for church-based schemes. In addition, there is a small World Vision outpost near Ezo town, supporting static primary health care clinics. Several agencies have plans for increasing activities, including UNHCR, but security considerations and logistical difficulties, including the lack of an operational airstrip, has prevented their implementation.

The area of Ezo was taken over by the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) in 1992. Since that time it has been relatively peaceful, although security deteriorated in 2005. There have long been tensions between the Azande and the Dinka, and the fighting that broke out around Yambio town in November 2005 affected relations between Dinka in the SPLA and local people in Ezo. Meanwhile, from across the Congo border there have been accounts of abuses by armed groups, and returning Sudanese refugees have been accompanied by Congolese refugees. A further security issue is the nearby presence of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA).

The LRA is an armed group that has been fighting the Ugandan government since the late 1980s, and has been engaged by the Sudan government as a militia in the war against the SPLA. It is renowned for the brutality of its methods, which have included mutilations, massacres of non-combatants, and the abduction of thousands of children. Warrants have been issued for the arrest of its senior commanders citing numerous ‘war crimes’ and ‘crimes against humanity’.Footnote6 The International Criminal Court (ICC) intervention is one reason why the LRA have sought refuge in the forests along the Sudan/DAC/CAR border. They remain a significant fighting force, and an attempt to execute the warrants by UN forces based in the Congo resulted in the deaths of soldiers involved. At present, the LRA is not attacking people in Ezo county, and is engaged in peace negotiations with the Ugandan government. The LRA commanders have told local Azande that they have no problem with them, and share an antipathy for the ‘Dinka’ – a term which is used to refer to both the Dinka people themselves, and those parts of the SPLA which are viewed as representing Dinka interests. There is an uneasy acceptance of their presence and, at the time of fieldwork, people did not live in fear of attack. However, relations with the LRA could suddenly change if the peace talks fail, and LRA bases are attacked.

Health data for Ezo county is poor. A survey carried out among internally displaced people in 2002 found that the main diseases were malaria, sleeping sickness, diarrhoea, respiratory tract infections, scabies, intestinal parasites, guinea worm, sexually transmitted diseases, and tropical (buruli) ulcers.Footnote7 However, it is not known how the information was collected. In June 2006, morbidity data was collated from primary health care (PHC) centres. The information available is incomplete (among other problems, the number of reporting centres varies from month to month), and are absent for most diseases that require laboratory testing, such as HIV and sleeping sickness, which is known to have re-emerged as a serious threat.Footnote8 According to the PHC data, malaria is the most commonly reported disease. Other common presentations are respiratory tract infections, acute diarrhoea, intestinal parasites, skin diseases, eye diseases and pneumonia. Among adults, presentations of STDs (sexually transmitted diseases) and genito-urinary infections are also frequent. Indeed, for adult men, this is the fifth most frequent diagnosis.

The relatively high numbers of patients presenting with STDs and TB might suggest that HIV/AIDS is a factor. But this is only speculation. Data on rates of HIV/AIDS infections for southern Sudan as a whole are very weak. It has been suggested that rates will vary greatly from place to place, and that in some locations prevalence (presumably for sexually active adults) may be around 7 per cent.Footnote9 However, almost all the evidence-based estimates appear to be derived from results of voluntary counselling and testing clinics (VCT clinics), and it cannot be assumed that they are representative of the general population. A network of sentinel surveillance sites are planned, but have not yet been established.

The most valuable VCT data relating to Ezo county has been collected by Zoa CitationRefugee Care (ZOA), which have run services since January 2004 at three sites in Western Equatoria: Yambio, Nzara and Maridi.Footnote10 In the first 12 months, 2,192 tests were done, of which 242 were return visit tests; 778 of these were in Yambio, 446 in Nzara, 478 in Maridi, and 248 in a Maridi-based outreach facility. Slightly more males (54 per cent) than females were tested at all the sites. Excluding return visit results, those found to be positive were: 14.2 per cent in Yambio, 20.6 per cent in Nyzara, 4.8 per cent in Maridi town, and 3.2 per cent at the Maridi outreach facility. In all cases, rates for females were around double the rates for males.

As part of the VCT process, clients were asked to respond to a questionnaire. Important points that emerged include the following:

| 1. | Rates for farmers were above the average, suggesting that living away from urban areas may not place people at a lower risk of infection. | ||||

| 2. | Food and drink sellers also recorded above average rates. | ||||

| 3. | Soldiers were found to be above the average in Maridi and Nzara, but below the average in Yambio. | ||||

| 4. | Students had the lowest rate of infection and were the highest self-reported users of condoms. | ||||

| 5. | Health workers had below average rates of infection. | ||||

| 6. | In Yambio and Nzara, HIV rates were highest in the 25–29 and 30–39 age cohorts. In Maridi the highest rate was among the 40 plus cohort. | ||||

| 7. | Less than 20 per cent of clients who reported high risk sexual contacts mentioned the use of a condom during their last high risk sexual encounter. Hardly anyone reported the use of condoms consistently. | ||||

| 8. | Most clients heard about VCT from friends, relatives, religious meetings and health workers. Few mentioned any information given in schools. | ||||

| 9. | In Yambio and Nzara, groups have been formed for people living with HIV, but this has not happened in Maridi. This may indicate that stigma directed at HIV positive people is lower in Yambio and Nzara. | ||||

Ezo is located between Yambio and Nzara and has a very similar population profile. Research in 2006 corroborated some of these findings – notably with respect to the use of condoms, setting up support groups and lack of information given in schools. The very high rate recorded by ZOA in Nzara, where some people from Ezo went to take advantage of the VCT service, is therefore a cause of serious concern. However, it needs to be stressed again that VCT rates may be a misleading indicator of overall rates. At present there are no ante-natal sentinel surveillance data and there have been no sero-prevalence studies. The only overall rate for Ezo is one of 2 per cent. This is based on a study undertaken by the International Medical Corps in 1999,Footnote11 but it is not known which population group it refers to, or how the data were collected. It may be a guess. Other available information includes a UNHCR survey of Western Equatoria in 2000. This found that 48 per cent of adults had never heard of HIV/AIDS, and more than 10 per cent of those who had heard of it did not know of the connection with unprotected sexual intercourse.Footnote12 In addition, research carried out in Ezo county by Phelan and Wood in 2005, found that HIV/AIDS was mentioned less often than in Maridi, that rape ‘is a continuing threat to many as they return home’, and that ‘stayees believe returnees will bring diseases with them from abroad’.Footnote13

The Azande People

The Azande are well known from the publications of E. E. Evans Pritchard and those of many other writers.Footnote14 In the earliest accounts, dating back to the 1860s, they are commonly referred to as the Niam-Niam. The term is probably of Dinka origin, and means ‘great eaters’. It refers to their feared, and not entirely spurious, reputation as cannibals. It also highlights a history of tension between the Azande empire and the pastoral people to the north.Footnote15

During the nineteenth century, the vast Azande homelands in what was to become Congo and Sudan were divided into kingdoms, with wide areas of unpopulated bush between them. The kingdoms had a well organised political system of headmen, chiefs and a king (or paramount chief). Each was ruled by a different member of a single royal dynasty, called the Avongara. Most chiefs were also from this same lineage, although there were some commoners who were appointed as governors. In the early years of Anglo-Egyptian rule in Sudan, there was initial resistance to the imposition of colonial authority but, following the death of king Gbudwe in a skirmish in 1905, the Azande proved, from a British point of view, to be friendly and malleable. The system of indirect rule they established acknowledged the Avongara hegemony, and king Gbudwe's sons and other relatives were incorporated into the new system of government. Nevertheless, according to Evans-Pritchard, the death of king Gbudwe was seen as ‘the end of an epoch, nay more, it was a catastrophe that changed the whole order of things’ (1976: xi).Footnote16 In the 1920s, when he carried out his fieldwork, the Avongara remained relatively aloof, and they still lived on the tribute paid to them by commoners (known as Ambomu and Auro), although their status was in the process of being weakened. Major Larken who was the District Commissioner at the time, was busy resettling the population in large settlements along the roads. This was done as part of a campaign to control sleeping sickness, but it also had the effect of intensifying direct administration, and undermining the authority of the chiefs. Footnote17

In his most famous book, Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic (Citation1937), Evans-Pritchard described in detail the ways in which Zande people interpreted misfortune, including illnesses, and obtained therapy and redress against those held to be accountable.Footnote18 He was able to show that beliefs in the power of oracles, and the existence of magic and witchcraft can form part of a logical system, one that worked as effectively in its own terms as that of ‘Western’ empiricism. Apart from its enormous impact on anthropology, the book has been seminal in the emergence of cross-cultural studies of medicine and healing, and has inspired a diverse range of other scholars, from philosophers of knowledge to social historians (e.g. Horton, Thomas, Winch, Triplett, and Jennings).Footnote19

In the years since Evans-Pritchard lived in Zandeland, there have been a series of social and political upheavals which, it might be assumed, has rendered his observations largely irrelevant today. In the later period of British rule, the resettlement of the population was reversed. During the early 1940s, what was then Zande District was selected for a pilot scheme, which was supposed to be part of the process of incorporating this part of Africa into the global economy. Between 50 and 60 thousand households were moved and dispersed across the countryside, where they were obliged to grow cotton. It was an unpopular policy, and became more so when the British officials and managers were increasingly replaced by Arabic-speaking, northern Sudanese. In 1955, the year before Sudanese independence, riots broke out, which were put down by the imposition of martial law.

The riots were a factor in the subsequent army mutiny of southern Sudanese soldiers, which is often cited as the start of the first Sudanese civil war. The Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972 brought a period of peace, but conflicts within the Southern Regional Assembly between a Zande-led Equatorian faction and groups associated with the majority of the Dinka contributed to the outbreak of war again in 1983. During the recent war, the Azande were initially hostile to the SPLA, but also had no sympathy for the northern government. Large numbers moved into neighbouring countries, although security there was by no means assured. Following the establishing of SPLA control over Sudanese Azandeland in the early 1990s, there has been an uneasy rapprochement, but tensions between local people and the Dinka soldiers in the SPLA resulted in the outbreak of fighting in late 2005 mentioned above.

Writing before some of these events, Eva Gilles observed in the introduction to the abridged version of Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic, that what Evans-Pritchard described is a ‘world long vanished’.Footnote20 Surprisingly, this is by no means entirely so. The Avongara have managed to keep a degree of their old hegemony. According to the current paramount chief, all the chiefs in Ezo county are still from the Avongara lineage. The paramount chief himself has a court near Ezo town where he hears witchcraft cases and arbitrates in disputes. He also has a system of headmen that is robust enough to impose fines on people who do not keep the paths to their homes clean, or do not have a pit latrine. Moreover, many customs and practices Evans-Pritchard analysed remain extant, although there have obviously been adaptations. Oracle specialists and witchdoctors nowadays assert Christian credentials, but what they do remains much the same as in the 1920s. Moreover, it would seem that, with the emergence of HIV/AIDS as a serious health threat and the absence of a credible public health response, demand for their skills may be on the rise. Unlike the primary health care centres in the county, which have no testing equipment, they can at least perform a kind of diagnosis. These and other findings from fieldwork in 2006 are discussed in the sections that follow.

Awareness of HIV/AIDS

If it is the case that 48 per cent of adults had never heard of HIV/AIDS in 2000,Footnote21 then there had been a remarkable change by mid-2006. Awareness of HIV/AIDS in Ezo county was found to be very high. People had been informed about the disease in church services, by county officials, chiefs and health workers. It is also widely known that some individuals had attended HIV/AIDS VCT (Voluntary Counselling and Testing) clinics, and that a few have openly stated that they are HIV positive. The disease is referred to as ‘echive’ (i.e. ‘HIV’), or as ‘sida’ (i.e. the French acronym – SIDA), or sometimes by Zande terms (ugudi kongo or kaza ango). The Zande terms are potentially ambiguous, and could possibly refer to other diseases too, so were always combined with ‘echive’/‘sida’ in asking questions. Here are some of the general comments people made about the epidemic.

HIV/AIDS is a disease that has come to kill everybody. There is no treatment. You just die.

(Group of women, Madoro, Ezo county)

The sickness has definitely defeated the Azande, because some sicknesses used to be treated locally. The only option is testing to know your status …

(Headman (aged 66), Naandi payam)

Now HIV/AIDS is living with people, you can bring awareness, you can bring test, but what is the use of bringing all these to us if there is no medicine for it?

(Male elder (aged 50), Andari payam)

We don't know how to protect ourselves because we can't identify who has it.

(Chief (elder), Andari payam)

Of the 381 adults asked: ‘Have you heard of HIV/AIDS?’, 95 per cent said yes, and 38 per cent said that they knew at least one person who is affected. HIV/AIDS was also mentioned as one of the worst health problems in the county by 71 per cent of those interviewed. Other health problems highlighted were malaria (57 per cent), diarrhoea (44 per cent), sexually transmitted diseases (31 per cent), sleeping sickness (24 per cent), worms (22 per cent), TB (21 per cent), cough (16 per cent), filariasis (14 per cent), and measles (14 per cent).The corresponding responses from the 53 primary school students were as follows: 75 per cent had heard of HIV/AIDS, 25 per cent said that they knew at least one person who is affected, and 75 per cent mentioned HIV/AIDS as one of the worst health problems. The other health problems noted by primary school students were malaria (38 per cent), STD (28 per cent), sleeping sickness (19 per cent), diarrhoea (11 per cent), TB (9 per cent), ‘cough’ (6 per cent), measles (6 per cent), and magic (4 per cent). These subjective answers are broadly similar to the clinical diagnoses reported from primary health care clinics, but with the striking difference that HIV/AIDS and to a lesser extent sleeping sickness are accorded so much significance. Those interviewed were asked about the ‘most serious health problems’ before being asked any questions specifically about HIV/AIDS. So it may be concluded that HIV/AIDS is generally perceived to be the worst of all health problems. Frequently cited reasons for highlighting HIV/AIDS were that most people who are infected are unknown – so will go on infecting others, and that HIV/AIDS is ‘incurable’ and ‘fatal’.

With respect to treatment, 81 per cent of surveyed adults and 72 per cent of primary school students stated that there is no treatment for HIV/AIDS. In addition, several respondents in both sample groups added more complicated answers, having heard that there is treatment available in some countries, but that it is not available in Southern Sudan. It is apparent from various comments made by respondents that it is not widely understood that medical treatment might control symptoms, rather than actually cure HIV/AIDS.

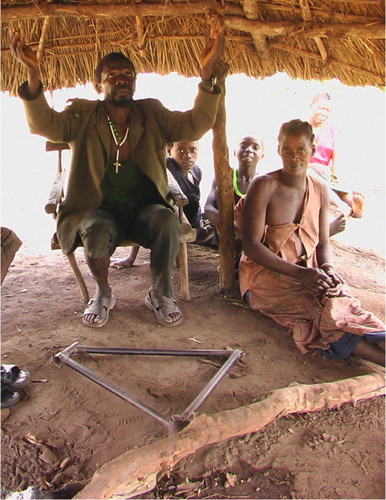

The numbers of respondents who reported knowing at least one person who is affected by HIV/AIDS is high (38 per cent of adults). It may be that some of those alleged to have HIV/AIDS (or to have died of AIDS) have in fact been affected by something else. However, there are a few people who have been tested, and who are open about their status. They have close links with the Catholic or Anglican churches, and play an active part in church services. In Ezo town, one of them makes a point of turning up at public meetings, and talks about his condition to anyone who will listen. He asked the author to take his photograph, and is seen here at the busy border market of Nabia Pia, surrounded by a group of young people, telling the story of his illness (). The following is an extract of his account.

I was born in 1978, and have been sick for two years. It started as joint pains in my legs and hands. Then there was diarrhea and skin rashes. I had a severe headache and I felt dizzy. Also my heart burned. … I went to traditional healers and oracles. The oracle told me that I might have stolen someone's money or that I had committed adultery. But I had not done those things, so it was false. They said I would die from the sickness, and that they had no cure. So I went for an HIV test in Nzara … I was not frightened when I went for the test. People thought I was dying already. … Before the test they gave me counseling. I was found to be positive, and I have followed the way of life they recommended. Their advice has made me feel better … I have protected myself and others by avoiding sex. Also I don't share razor blades. The disease has to be stopped. It should not be spread. Now I need medicines for symptoms, hygiene, and a balanced diet … I don't know how I caught the disease. Maybe from a razor blade or from a needle (syringe) or from sex. I did have girl friends, a few of them. Also a wife … I was advised not to be shy about the disease. Those who are secretive are the ones who want it to spread. The person who is open can give advice. I share my experiences with others, and I have formed a group for positive people. Church leaders are also in the group. They help us with the word of God. Sometimes they contribute with food … I am totally dependent on assistance from people. … Some people fear me and do not like me. They think I might infect them. But most shake hands with me, and even share food with me.

The activities of individuals like this, combined with announcements in public places, have evidently contributed to awareness about HIV/AIDS. Many people had also been informed about the epidemic when they were living in Uganda, DRC or the CAR. However, it is important to stress again that there are no adequate prevalence and incidence data, and rates may well be less than are imagined. Azande men are circumcised, which has been shown to halve the risk of adult males contracting HIV through heterosexual intercourse.Footnote22 A danger at the moment is that there is so much concern about HIV/AIDS that other diseases are ignored, or assumed to be a consequence of HIV. As a group of men interviewed at Nabia Pia market put it: ‘If someone has a disease like malaria or sleeping sickness and begins to change shape (become slim), people will suspect it to be AIDS.’

Knowledge about Transmission and Symptoms

Sexual intercourse was mentioned as a way of becoming infected by 84 per cent of surveyed adults and 74 per cent of primary school students. Other modes of infection mentioned were needles and syringes (34 per cent of adults and 11 per cent of primary school students), razor blades (38 per cent of adults and 2 per cent of primary school students), open wounds (7 per cent of adults), touching blood (6 per cent of primary school students), and blood transfusion (20 per cent of adults). There is virtually no awareness of mother to child transmission.

An emphasis on sexual intercourse and to a lesser extent blood contact was similarly highlighted in open ended discussions, as illustrated by the following set of quotes.

The factors leading to catching AIDS are that our sisters do not refuse foreigners. I mean they are like prostitutes, because they are after money. It is travellers who cause it. Look at where they spend the night … and at what they do [with local women]…

(Teacher, RCC Primary School, Naandi payam)

Commercial sex increases the spread of HIV/AIDS in our country. And also those who come from outside. They infect us, because people don't protect themselves from unsafe sex.

(Group discussion with county staff, Ezo Centre)

Travellers and truck drivers are the biggest risk. They come from countries like Uganda, where they are exposed to sex …

(Male trader at Nabia Pai market)

Travellers, immigrants and youth are carriers of AIDS, and traders too as they get through a lot of sex and sharp objects [e.g. they use razor blades to cut their hair and shave].

(Group of traders at Nabia Pai market, Ezo county)

A problem is that people have many wives/girlfriends and inherit widows [i.e. a woman whose husband dies is expected to have sexual relations with one of his brothers].

(Group of officials, teachers and representatives of youth and women – Naandi payam)

It is spread because of our traditional ways of getting new wives/girl-friends by going in a hidden way outside marriage. Polygamy may cause AIDS. Also widow inheritance.

(Deacon, Naandi payam)

We are at risk, because they [boys] indulge in a lot of sex.

(A group of girls at Baikpa IDP camp)

Everyone agrees that markets are a particular place of risk. is a picture of Nabia Pia weekend market, located at the border of the Sudan, DRC and CAR. People come from diverse destinations, and many end up staying the night in the vicinity. The traders have money, and alcohol is consumed. High risk behaviour is reported to be common.

While sexual intercourse and contaminated blood is emphasised, there are also other views which do not relate so closely to biomedical understandings. Some of those surveyed mentioned infection from, kissing (6 per cent of adults and 2 per cent of primary school students), sharing food (5 per cent of adults and 4 per cent of primary school students), urinating in the same place (3 per cent of adults and 2 per cent of primary school students), mosquito bites (9 per cent of primary school students), and sharing bathing water (2 per cent of primary school students). These ideas may be connected to health messages relating to other diseases – for example, messages about personal hygiene to avoid diarrhoea and about the use of bed nets to avoid malaria. These and other alternative explanations were more commonly mentioned in open-ended interviews, which elicited a wider range of personal worries and views. Here are examples.

HIV/AIDS is a disease of monkeys. It does not affect people in our country. I don't know why people are worried about it. You will only get it if you eat monkeys.

(Group discussion, Nanzinga, Ezo)

You will not get HIV/AIDS if you drink urine, as well as eating good food and abstaining from sex. But it is a dangerous disease, because somebody can be infected by sharing clothes.

(Group discussion, Nanzinga, Ezo)

We do not know how somebody becomes infected with HIV, but we hear that it is caught when women twist their hair, when people sit together in the same chair and also having sex. To avoid infection, you should stop drinking alcohol, stop smoking, and stop eating with infected people and stop sharing seats with them.

(Group discussion with county staff, Ezo Centre)

Somebody may have conflict with another. Then they fear that he or she may ‘poison’ food by pouring blood containing AIDS on the food.

(Group of women and traders at Nabia Pai market, Ezo county)

Aids can be caught by sharing hair combs.

(Group of girls at Baikpa, Ezo)

You can catch AIDS by sharing left over food and by sharing a toilet, as well as from sharp objects …

(Group of men at Nabia Pia market)

We think that AIDS is spreading at a high rate, because of uncontrolled coughing, sharing beds, kissing and through contaminated water.

(Group of women and traders at Nabia Pai market)

When a man is said to suffer from AIDS and dies, we find his wife is healthy. So we say he was poisoned or bewitched, and we should not fear the disease … [i.e. even if someone has symptoms of the disease, it is the sorcerer or witch who has actually caused the person to be afflicted].

(Group of men at Nabia Pia market)

Several of those interviewed also posed their own questions. These could be very revealing of underlying fears and confusions.

Are chances of infection higher if you have sex with a woman during menstruation?

(Lab assistant (aged 37), Naandi payam)

Is it true that when a woman is positive, she will not menstruate?

(Catechist (aged 43), Naandi payam)

Last month I had a severe headache for 2-3 weeks. I was told by elderly people that it was obviously the sign of AIDS. Was it true?

(Man (aged 43), Naandi payam)

Does AIDS also affect the brain, like sleeping sickness? Is AIDS the only cause of skin rash? I was told that lubricants on condoms make you sterile. Is it true? Is it true that people with gonorrhoea cannot be infected with HIV? Is it a clear indicator of being negative? My penis does not fit in a condom. What should I do to have protected sex? Is it true that much friction during sex increases the risk of HIV?

(Young man Naandi payam)

Such specific inquiries about signs and symptoms reflect an appreciation that HIV positive people might not look ill. For example, a group of 10 men interviewed at Nabia Pai market remarked that, ‘One may look smart and healthy – meanwhile being infected.’ In the survey, 45 per cent of adults said that it was not possible to know if somebody has HIV/AIDS infection. Symptoms mentioned by those who thought it was possible were becoming slim or anaemic (50 per cent), diarrhoea (26 per cent) and skin rash (18 per cent). Answers from primary school children were similar. One of the reasons why several respondents were able to give specific details about signs and symptoms was because of the activities of those HIV positive people who are publicly explaining their affliction to others. One of these openly shows people the indications of the disease on his body. In this picture, he has asked for his skin rash to be photographed by the author (). He was at the time surrounded by a group of interested people.

Knowledge of How to Avoid Infection

In responses to the structured surveys, both adults and primary school students most frequently emphasised ‘faithfulness’ and ‘abstaining or avoiding sex’ as the most effective ways of avoiding infection ( and ). When asked why, they referred to messages given out in church services and community meetings by Christian activists, health workers, HIV positive people and other local leaders. Here again there was a tendency for answers to reflect what people had been told, rather than the full range of their own perceptions, and open-ended discussion quickly revealed more complicated views.

Table 1. How can you avoid an HIV/AIDS infection (381 respondents)? Respondents above 15 years.

Table 2. How do you avoid becoming infected with HIV/AIDS? Primary School students, 53 respondents.

The emphasis on razor blades and sharing needles in responses to both this question and the one on modes of transmission is interesting. There may have been exaggeration in HIV/AIDS awareness messages. Contraction of HIV would require the use of a razor blade or syringe relatively soon after it had been contaminated with infected blood, and is still unlikely if contact only occurs with peripheral blood (such as in an intramuscular, rather than an intravenous, injection).Footnote23 However, adult concern about razor blades in particular is also connected with fears about HIV positive people deliberately infecting others, an issue discussed in sections below.

Respondents were also asked specifically about their use of syringes; 43 per cent of adults and 58 per cent of primary school students stated that they inject at home. In open-ended and focus-group discussions, several also stated that they share needles with family members, because they are too expensive to be thrown away. However, responses to the question in the surveys: ‘Do you share the needle with other family members?’ indicate that the risks of doing so are well known; 82 per cent of adults and 79 per cent of primary school students denied doing so.

Most respondents had heard of condoms, and a minority were enthusiastic about them. Condoms are available for purchase at certain shops in town centres, and are supposed to be given out at primary health care centres (although no informant stated that they actually obtained condoms from this source). Nevertheless, relatively few respondents mentioned condoms as a possible way of avoiding HIV infection, and the majority stated that condoms are not being used (72 per cent of adults). Staff interviewed at the lodge at Ezo town reported that they occasionally find used condoms in the morning, usually when rooms have been occupied by ‘outsiders’ (e.g. traders from Uganda or Congo). They also told stories of how local women are shocked when men put them on, and sometimes run away.

Interestingly, the percentage of respondents saying that condoms are not used was lower among primary school students (53 per cent). As noted above, the survey run by ZOA in neighbouring counties in 2005 found that students had the lowest rate of infection and were the highest self-reported users of condoms.Footnote24 This is probably the case in Ezo too. A few of the older male students stated in front of their class-mates that they used them – and even suggested that condom use should be made compulsory. There were also a minority of men and women, most with above average levels of education, who openly said in focus group discussions that they would like to use condoms, but found it difficult to do so. Here are some examples.

We need to know our status, and also to have enough condoms. Why can't the NGOs responsible for HIV in this area supply us with that?

(Group of officials, teachers and representatives of youth and women – Naandi payam)

For the case of condoms, why can't people bring the big size? The ones we have are small and can burst and cut. … We would like to use them, but our ladies say that sex is not sweet with condoms. Also a woman cannot become pregnant.

(Group discussion, Nanzinga, Ezo)

The first condom that was brought was called Lifeguard. Then they brought Protector. Lifeguard bursts and Protector splits or falls off in the vagina. Which one is best?

(Group of men at Nabia Pia market)

Men who say that they use condoms sometimes explained that sexual intercourse with them does not really ‘count’. For example, one educated informant told the author that he is a Christian and happily married, so if he ‘goes outside’ for women, he always uses a condom. His wife knows this, but is content, because he was not really having sex. Others interviewed expressed somewhat similar opinions. However, responses to the survey questions indicate that it is much more common for condoms to be rejected. The Christian churches have been teaching that they should not be used, and for many of those interviewed, condoms prevent sexual gratification, as well as pregnancy, and may even be dangerous. The following quotes from semi-structured interviews and focus-group discussions capture prevalent attitudes and beliefs about condoms, and reflect the lack of understanding among some informants about how they should be used.

People say there is no love in the use of condoms. Only body to body can it be felt.

(Health worker, Andari payam)

Most of the ladies when they see a condom, they refuse sex. Condoms are not needed, because they cut the vagina of the lady. There is also no pregnancy with condoms. Sex is not sweet with condoms. They are against our religion.

(Group interview with secondary school students, Ezo)

One man used a condom and it was stuck in the woman until local villagers came to pull it out.

(Group of men at Nabia Pia market)

In our religion we know that using a condom is not good, because how shall we bear children … (But) they will enable us to survive in the future.

(Woman (aged 20), Ezo)

Some people say that if there were condoms for their fathers and mothers, then they would not have existed. So we should avoid their use to have children.

(Group of men at Nabia Pia market)

We hear of condoms, but the use of them is not available. Where are they kept? Is it in the hospital or the shop? We have never seen it (i.e. a condom). And there is no need for their use. Common people do not use them, but only foreigners from Uganda and Kenya who pass through.

(Group interview with secondary school students, Ezo)

HIV/AIDS and Local Healers

A question asked in the structured interviews was: ‘If people have HIV/AIDS who do they consult?’ ( and ) It was assumed that ill people and their relatives are likely to consult several different kinds of healers during their quest for therapy, so respondents could give more than one answer. However, most only mentioned one or two. The categories of healer were chosen in a participatory workshop with the local researchers. Given the fact that many of the local researchers were known to have links with World Vision and the primary health care centres, it is unsurprising that health workers are mentioned as the most likely specialists to be consulted. The high number of responses recorded as ‘other’ by the primary school students was because many stated that they would consult their friends and/or parents.

Table 3. If people have HIV/AIDS, who do they consult? 381 respondents aged 15+ (more than one answer possible).

Table 4. If somebody thinks they have HIV/AIDS, who do they consult? 53 primary school students (more than one answer possible).

An interesting aspect of responses to the question from both groups is the relative frankness about local healing. In open-ended discussions, many respondents stated that those who think they are HIV positive will consult various kinds of non-biomedical specialists, including diviners, oracles and ‘charismatics’ – Pentecostal Christians – who heal by prayer and the laying on of hands. Few felt the need to deny or hide such activities; in spite of the fact that Christian leaders associated with the established churches have been teaching that such therapists are charlatans or ‘Satan worshipers’. It was also accepted by several of those interviewed that local specialists can accurately diagnose HIV/AIDS, although they might not be able to treat it. For a few informants, even treatment is a possibility.

Yes there is a treatment for HIV/AIDS from our own people, such as ‘bird keepers’[a special kind of healing specialist and oracle], eating cooked dog, and a man called XXX [name given by informant] in Yangiri payam. He can cure the disease using his own methods. Also a man called XXX [name given by informant] was cured from AIDS through charismatic prayer, and he is here living still among us. Other people also are cured when they pray a lot.

(Group discussion with county staff, Ezo Centre)

On the other hand, it is not just Christian leaders who are critical of some local healing, as the following quotes illustrate. The reference to sharp objects relates to the technique of cutting the skin of patients, to rub concoctions into the blood.

Traditional healers increase the rate of sickness by pretending to cure what they cannot cure … Most HIV/AIDS infected people are taken to them. A healer [informant gives a specific name] pretends to be curing HIV/AIDS. He has trained X [informant gives another name]. [People think] he can treat most deadly diseases.

(Group interview with secondary school students, Ezo)

The place where people share sharp objects is with traditional healers. He will cut many people with the same razor blade, and may also use syringes.

(Chief, 34 Makpudu, Ezo)

Attitudes to non-biomedical healing must be placed within a context of pluralistic aetiologies of illness. The Azande (like many other African peoples) tend to ask ‘why’ as well as ‘how’ questions about misfortune. They may accept that someone has a particular disease or has suffered an injury in an accident. They nevertheless also tend to ask why that particular person suffered such a misfortune and not someone else. In the 1920s, according to Evans-Pritchard, the answer was often witchcraft and sometimes sorcery. Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic begins with the following passage:

Azande believe that some people are witches and can injure them in virtue of an inherent quality. A witch performs no rite, utters no spell, and possesses no medicines. An act of witchcraft is a psychic act. They believe also that sorcerers may do them ill by performing magic rites with bad medicines. Azande distinguish clearly between witches and sorcerers. Against both they employ diviners, oracles and medicines.Footnote25

The spread of Christianity, public health interventions, formal education and the political and economic upheavals of the past 80 years have had a profound impact on the ways people conceptualise personal afflictions. It is nonetheless the case that the beliefs and rites that Evans-Pritchard described have proved to be resilient. Even in the 1920s there was debate about them. Alternative explanations were often put forward, and a range of therapists consulted. Today Christianity and bio-medical ideas about diseases play a more significant role, but ‘witchcraft’ (magu), oracles (soroka) and magic (ngua) remain prevalent. At one level, all deaths are still interpreted as a form of homicide, and those accused of witchcraft (or sorcery) are taken to the chief's court (), as is explained by the paramount chief of Ezo county.

I deal with crimes and community problems at my court. In cases of witchcraft, people will first have visited an oracle. The one who is accused will come to my court and will swear on the Bible that he is innocent. Sometimes he is given a special water to drink. If he vomits, then he is the one. It confirms he is a witch. I deal with one or two cases of this kind per month. The oracles we use at the moment are not the most effective ones. For that we need to obtain benge [a special poison] from Congo. If the situation stabilises, we will get it.

(Paramount Chief, Ezo county)

In this interview, the paramount chief is referring to a form of strychnine derived from a certain jungle creeper, unavailable in most of Ezo county. As in Evans-Pritchard's time, it is universally regarded as essential for the most accurate kind of oracle. It is administered to chicks, some of whom survive, while others die. The oracle specialist then interprets the answer from having observed what has happened. In pre-colonial past, benge was also administered to humans. From the paramount chief's statement, it would seem that some kind of poison is still used in this way, but such a procedure was not witnessed by the research team, and clearly the special water nowadays administered to the accused is not lethal.

In the absence of benge, other oracular methods are used. All of those observed are different in detail to the non-benge oracles described by Evans Pritchard, but follow the same principle. Questions are asked, and the oracle gives a yes or no answer. Evans-Pritchard refers to a corporation of witchdoctors or diviners, known as abinza (or avule) who were believed to combat witchcraft ‘in virtue of medicines which they have eaten, by certain dances, and by leechcraft’.Footnote26 Leechcraft refers to a technique of sucking witchcraft substance out of the patient's body. He also mentions boro ngua, other people who possess magic and who practise leechcraft. In addition there were the oracles (soroka). Certain simple kinds of oracle tool were owned by lots of older men, who would consult them at the request of friends and relatives. Others, such as the benge oracle, required a specialist, who was often associated with the courts of chiefs.

Nowadays, there is less distinction between the types of person consulted. All the local healers visited combined divination with the use of oracles, herbal remedies, leechcraft and magic. Older men were not found to be using their own oracular devices, but this may be because the churches have been preaching against their use, and that they are consulted discreetly. The healers interviewed countered any implications of impropriety by asserting a Christian aspect to their actions. They included prayers in their oracular consultations, and one of those visited had turned his place of work into a kind of church. They have also adopted practices associated with clinical practice, such as having separate wards for patents and their families, and sometimes giving advice about diseases. All claimed to be able to diagnose HIV/AIDS, but said that they could not cure it. Only one healer was thought to be able to do that – the man mentioned in the quotes above (it was not possible to talk to him during field research). Those diagnosed as HIV positive are sometimes given local treatments for HIV/AIDS symptoms, such as skin rashes and diarrhoea, although one healer visited explained that his treatments are too powerful for someone who is already very weak. All the healers said that they always tell HIV/AIDS patients to stop having sex, and to go to the health centres for advice.

HIV/AIDS, like other potential ailments, is diagnosed by asking the oracle a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ question. In the case of the rubbing stick oracle (), the inner stick becomes wedged in the outer stick if the answer is yes. In , a different healer prays to God to help his diagnoses. At his feet is an old bicycle frame. When the answer to a question is ‘yes’, it becomes stuck to the ground and cannot be lifted. This particular healer is one of the most highly respected in Ezo payam. He operates in a remote place that can only be reached by wading through a bog. He was visited by the author on a Sunday, so he was not actually working. Groups of patients were waiting with their families to consult him the following day, including a woman who had been paralysed, probably by witchcraft or sorcery. Another patient had undergone a minor operation for a tropical ulcer in his leg, which the primary health care centre had apparently failed to cure. It had been cut out and treated with an herbal concoction, one that had been revealed to the healer in a dream.

is a picture of another healer who asserts a strong Christian connection. He is photographed holding a rubbing stick oracle. He also uses a special chair, which cannot be moved if the answer is ‘yes’, and a bottle of magical water, in which the water remains motionless if the answer is ‘yes’. He wears a dress that is similar to those used in church services, and has crucifixes drawn on the ground with chalk. Some of his herbal remedies are also shown in the picture, as well as a packet of razor blades used to cut the skin of patients so that concoctions can be rubbed into their bodies.

Zande beliefs in witchcraft, oracles and magic remain strong, and have adapted to changing circumstances. A very important point to consider is the following. The Zande conception of witchcraft (mangu) has striking similarities to local perceptions of HIV. A witch and an HIV positive person may be doing dreadful things, while appearing normal and harmless. In addition there may also be those who are positive who act as sorcerers (ira ghegbere ngua). Like sorcerers they may use things to deliberately harm others, such as mixing their blood in food or leaving a contaminated razor blade on a path. It is small wonder that Azande express such fear of HIV/AIDS, exaggerate the danger of infection from sharp objects, and turn to diviner/oracles for protection and guidance.

Sexual Practices

Zande sexual practices have been remarked upon since colonial times. One of the earliest accounts of their customs, written a hundred years ago, makes the following comments.

In their notions of embryology they believe that the foundations of the foetus are not laid in one impregnation, but in several successive fertilisations of the ovary extending over a number of days. … They practice polygamy, and the number of wives a man may have depends entirely on how well off he may be. … Neither the men nor the women are particularly faithful to one another, and absence from one another for more than five or six days puts a great strain on their self control. … Syphilis is very common …Footnote27

Such remarks may have been influenced by contemporary prejudices and misconceptions. Nonetheless, comparable comments about Zande sexuality appear repeatedly in the literature. Evans Pritchard discussed what he called ‘Zande sex habits’. Drawing on his fieldwork in the 1920s, he described ways in which men and women sexually gratified each other; observed that men were expected to copulate frequently and noted that ‘Azande do not attach very much importance to virginity’.Footnote28 He found too that women were expected to take an active part in their own and their partner's satisfaction. From an early age they learned how to make a rotary movement of the muscles of the lower abdomen. It was used in play by little girls and was prominent in certain dances. In the sexual act it was employed to massage the penis while it rested in the vagina. He explained that men considered it essential for a really satisfactory copulation that the penis should be well gripped:

Nothing is so disappointing to a Zande as to lie with a woman who has what they call a large watery vagina so that in the backwards and forwards and rotary movements of the sex act the penis keeps on slipping out. They like a vagina which is what they call sticky and small, which is difficult to enter, and which grips the penis firmly when entrance has been effected. Men dislike a vagina into which they merely slide the penis easily, preferring an effort for insertion, pushing slowly and with greater friction to the organ and so greater pleasure. … But though men like a slightly difficult entrance, they dislike women with an exceptionally small vagina, which is regarded as an affliction (ima kpatakpali).Footnote29

Similar attitudes about an ideal vagina, and a woman's skill in using it, were expressed in 2006. Indeed, people could be surprisingly candid about sexual matters. Here are three examples. The first is from a focus group discussion with women:

If two people agree to have sex, they do it in the home or in the bush. Some people go straight for the sex, whereas others have foreplay to prepare them for sex. People have heard about condoms, but we do not use them. While having sex, the woman can touch the man's penis and direct him to the vagina. The man sometimes touches the vagina to prepare the woman for sex, normally concentrating on the clitoris to stimulate the woman. But, sometimes men just penetrate without preparation and the woman experiences a lot of pain during sex.

(Group of women, Madoro, Ezo county)

The second is a statement made by a man at Nabia Pai market.

Sexual intercourse (often) takes place in the bush. Sometimes married people engage in sex outside marriage. If the wife is discovered, she will be beaten by the husband and taken to the local (traditional) court. A man normally negotiates with a woman before sex. If they agree, they may have sex in a friend's house. Before the sex, they play about and kiss, and remove their clothes. They touch each other's organs. The girl touches the penis, the boy touches the breasts. In Ezo people hear about condoms, but they do not like to use them. They prefer body to body contact.

(A man at Nabia Pai market)

The third is a song, which was sung by one of the local research team as an ‘ice-breaking’ activity. It is well known, and all the Zande researchers, including the women present, joined in the chorus. It compares the wet vagina of one girl with the dryer and tighter vagina of another, indicating that the first is unappealingly lubricated and the latter provides satisfactorily friction.

Tiareke oo is watery like a flowing river, Martha the daughter of Anarika is like badly cooked cassava leaves (Tiaieke oo zabo-zabo wa no ime, Martha wiri Anarika wa bido gadia ngabo ngabo).

(Popular song, sung at dances)

Although relatively dry sex was preferred, no evidence was found of anal sex either between heterosexual or homosexual couples. It may occur, but all those asked about it deny that it happens. Evans-Pritchard noted similar responses in the 1920s. However, he also discovered that in the past there had been homosexual and lesbian relationships, in part due to the custom of polygamy. The former tended to occur between a warrior and boy, who would act as his ‘wife’. The latter sometimes occurred between co-wives. In both cases the sexual act involved rubbing bodies together rather than any from of penetration. At the time of his research, homosexuality was no longer openly practised, but many elders described it to him. When asked today about these historical practices, respondents vehemently deny that they ever happened. Typical responses are: ‘Sex is always between a man and a woman’ and ‘There is only one sexual practice using the normal organs which God created for multiplying.’

The denial of homosexual practices may be linked to Christian influence, but it is also likely to be connected with the lifting of sexual constraints on young men. In the past it was almost impossible for most men to marry until they were in their twenties or thirties, because young women formed sexual unions with much older polygamous men, and because Zande princes had large harems. Wife inheritance was also practised, whereby a widow would form a sexual union with one of her diseased husband's relatives. The result was that there was simply a shortage of marriageable women. Young men either had to turn to boys or to adultery. In the 1920s, the weakening of the authority and power of the chiefly class was already making more young women available. Today, polygamy and wife inheritance are still practised, but are much less pervasive than they once were, and both young men and young women encounter few restrictions to sexual encounters. Young men look for partners without the regulation that used to be imposed by elders, and will resent efforts to reintroduce them. Young women too are said to have sexual intercourse for their own pleasure or, allegedly, to obtain money and gifts. Here are a few rather typical statements from focus group discussions:

Sex is not only practised in marriage, but also outside marriage. The youth indulge in sex before marriage.

(A group of girls at Baikpa IDP camp)

A problem with polygamy is that a man may not be able to satisfy (his wives) sexually. So women may move out [i.e. have sex with other men].

(A man at Nabia Pai market)

Some people go for sex outside of marriage. When one's spouse goes outside for sex, one will say, ‘I can't bear my sexual feelings’. He or she will also go outside and ‘play’ sex there.

(Group of women and traders at Nabia Pai market)

The problem has arisen because there is a high rate of prostitution. People should avoid being after money.

(Headman (aged 66), Naandi payam)

The sexual practices here are people do have sex at random without care or control.

(A man (aged 37), Naandi payam)

There is no respect in sex nowadays, especially when they go to the market and drink beer there is no control.

(Group interview with secondary school students, Ezo)

Back in the 1920s, elders complained to Evans Pritchard about the behaviour of the youth, so perhaps not too much should be read into assertions that they are beyond control. However, young men in particular have much to say about their sexual activities and sexually transmitted diseases are a frequently reported ailment. It is also clear that stability of sexual unions takes time to establish, and probably more so than in Evans-Pritchard's day. The various exchanges of bride-price may only commence after the birth of a child, and may go on for years. Given the upheavals of recent years, it may actually be impossible to pay anything. Marriage has always been a process rather than a single event, and when informants talked about being married, they mostly meant beginning a sexual relationship, rather than embarking upon a long term commitment. Healthy young men in particular are expected to have a need for frequent sexual intercourse. One observed that:

As a youth I travel for business by bike. I am at risk, because I have sex at random wherever I go.

(Young man at Nabia Pia market)

An issue raised in the report on return and resettlement by Phelan and Wood (Citation2006), is that rape is a threat. In circumstances in which social norms and controls are not yet re-established, and in which there are various armed groups operating both in Ezo county itself and in all the neighbouring territories, gender-based violence might be anticipated. It was not, however, an issue that was raised by many of those interviewed. It was mentioned by some groups of women, but they did not claim to be reporting their own experiences. It was said that a raped woman is likely to keep the event secret, unless she becomes pregnant. Interestingly, only one of the school drawings discussed below depicts rape, and that was made by a French-speaking teacher who had migrated from Congo. Women are probably more vulnerable when they are moving from neighbouring countries than they are in Ezo county itself. One reason why that may be the case is that the traditional system of chiefs and headmen functions surprisingly well, and men acting in overtly antisocial ways are checked (for example, even on market days it is relatively unusual to see drunken people).

Here are some statements from focus group discussions, illustrating both an openness to discussing sexual practices, and an awareness that current behaviours may put people at risk of HIV infection. The first is a series of statements taken from a focus group discussion with staff at the lodge (a small local hotel) in Ezo centre. They relate to points in this sub-section, as well as those raised previously about attitudes to condoms.

People come to the lodge in good numbers. At times ten or more. They bring women with them for sex. Sometimes they ask us to go and search for ladies for them. We know some ladies who we can go and bring here for sex at any time, night or day. Those ladies need money after sex. … Sometimes we see the covers of condoms inside the rooms – but not usually. Although when Ugandans come to sleep with ladies in the lodge they use condoms. … Recently I saw a lady who came outside the room and ran away from the man, because he wanted to use a condom. Most Zande girls do not want condoms for the following reasons: sex is not sweet with a condom, you cannot give birth, our religion is against condoms, and a condom remained in the vagina of a certain lady and she died. … When they play sex with condoms and leave the cover inside the room, and we come to collect it in the rubbish, can we be infected?

(Interview with staff at Ezo Lodge: manager (aged 28), watchman (aged 37), cooks (aged 20 and 21))

The next selection of comments is from a group of men interviewed at Nabia Pai market. It reflects a view expressed by many young men, that having sex with several partners is inevitable.

Sex takes place anywhere: in the market, on the road, at the lodge, at a friends house. It happens at night. … No there is no foreplay. … For us youth, young girls may come from elsewhere, including other countries. As we try to engage and get into sexual contact with them, we end up being infected. … One may look smart and healthy – meanwhile being infected … You may find one pretty girl from Uganda or Yambio. You are longing to have sex with her by all means. But no condoms are available. She may be infected. … Girls are responsible for the spread of AIDS. They should be tested and those positive be given a t-shirt for recognition … I may protect myself, but if I have married (i.e. have sex with) a woman who is infected already, then what can I do?

(Comments from a group of men at Nabia Pia market (10 participants))

Children and Adolescents

A primary objective in controlling an HIV/AIDS epidemic is to reduce the rate of new infections. Partly for this reason, fieldwork in 2006 placed a particular emphasis on the vulnerability of children and adolescents. One issue that could not be investigated, due to lack of testing facilities, was mother to child transmission. It was mentioned by girls interviewed at the secondary school in Ezo town, but most people had never heard about it.

‘Child headed households’ or ‘AIDS orphans’ were also not cited as problems. The only person who mentioned the notion of an AIDS orphan was an HIV positive man who has been trying to establish a ‘living with HIV group’ to attract assistance and funding. This does not necessarily mean that AIDS orphans and child-headed households do not exist. If these categories begin to be used by government officials, health care workers and aid agencies, as they have been elsewhere, then many people can be expected to come forward. There are certainly numerous mothers who are less than eighteen years old, and whose marital status is flexible or ambiguous. Similarly there are doubtless large numbers of children who have lost at least one biological parent. However, at present they are absorbed into kinship networks. Even women who do not see themselves as being in a stable marriage state that they did not want to use condoms partly because they want to be pregnant. Women are supposed to give birth, and there is a widespread view that children are a blessing. The Azande are certainly not unique in this respect, but there are particular reasons why reproduction is emphasised and all births welcomed.

First, since the early twentieth century there have been concerns that the fertility of the Azande people has been in decline. Whether or not this is objectively accurate is unknown, but it has been frequently asserted that the prevalence of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases is high, and that this is a cause of infertility. It is a view that is expressed by Zande people themselves. Second, the Azande areas of Western Equatoria remain sparsely populated. In the last census, carried out in the early 1980s, the Azande were the second largest ‘tribe’ in southern Sudan. Many have migrated abroad. There are also large numbers of Azande who have traditionally lived in what are now the DRC and the CAR. In Ezo county a commonly mentioned issue is that the population must increase rapidly, both by procreation and migration. There is plenty of room for people to settle, and there is talk about an urgent need for a large Azande population in Western Equatoria to ensure that the Dinka do not assert control.

By far the most surprising finding about children was the extent of their sexual knowledge. One aspect of this was the reported ages of sexual debut. A question in the structured surveys was: ‘When do boys and girls first have sexual intercourse?’ Answers from the 53 primary school students produced an average of 17 years for boys and 15 years for girls. However, this may have simply reflected the fact that the primary school children were at school, and therefore had an incentive to wait before starting a family or taking on familial responsibilities. The ages of sexual debut reported by the 381 adults was much lower. The sample of adults reported an average age of sexual debut for boys of 13 years and of sexual debut for girls of 12 years. In open-ended discussions, even younger ages were mentioned. Several informants maintained that sexual debut in girls occurs at around 10 years, before menstruation begins.

It was repeatedly stated by adult informants that talking about sex to children is impossible, and that sexual knowledge is obtained from peers and from practice – or perhaps by watching parents at night. Children might have their first sexual experiences with one another, and they practise love-making from an early age. Understanding of sexuality is supposed to come naturally. Adults asked about when they first found out about sexual intercourse said that they could not remember ever having not known about it. Adults are also embarrassed about the notion of sex education. Some stated that a child who asked a question about sex to an adult, including their own parents or an older sibling, is likely to be chastised. To raise sexual issues across generations is said to be unacceptable. Here are some comments from focus groups discussions on the topic.

Sex matters are not discussed between parents and children, or with (older) siblings. … Before boys and girls have sex, they first agree on the location. They have foreplay, and engage in sex when they are ready.

(A group of girls at Baikpa, Ezo)

Children are not allowed to enquire about sexual matters from their parents. They are beaten if they ask. Also, there is no sex education in churches and schools.

(Group of women, Madoro, Ezo)

Sometimes sex takes place before the age of 10. No sex matters are discussed openly. Before sex there is foreplay, like kissing and playing with the sex organs before the real sex act takes place.

(Group of women at Baikpa Ezo)

I have seen children of 5 or 6 years practising sexual intercourse with each other. When I asked them about it one said, “I saw my mother doing it with my father.”

(Group discussion, Nanzinga, Ezo)

Taking into account statements from adults about talking to children directly about sexual intercourse, it was decided to focus research on students in the last two years of primary school in Ezo payam. Not all the children gave their ages, but the range was about 12 years to 17 years. Contrary to expectations, they proved to be well informed about sexual intercourse, and most were willing to talk about it openly, once initial shyness was overcome. To initiate discussion, they were invited to submit drawings for competitions. The winning entries were given t-shirts. Fifty-five entries were submitted. The children were asked to draw a picture of ‘How is HIV/AIDS spread in our community?’ Of the 55 entries, 27 depicted the sex act; 11 depicted sexual intercourse being proposed; 14 depicted razor blades; 11 depicted the use of syringes; 2 depicted condoms; 1 depicted contaminated food, and 1 highlighted the danger of kissing. Many of the pictures showing the sex act were remarkably explicit, and one of the most graphic was by a boy of around 10 years who had crept into the back of the class, and submitted a picture drawn in his notebook. shows some examples of drawings showing the sexual act. Note that two of the pictures demonstrate knowledge of condoms.

Figure 8. Drawings by primary school children, showing copulation, use of a condom and how people become infected with ‘sida’.

Another drawing competition with the same title was held at the secondary school in Ezo town. Thirty-four students and two teachers entered the competition; 20 drew a picture of the sex act; 8 depicted propositioning for sex; 3 paying for sex; 1 kissing. and 1 rape (the Congolese teacher mentioned above). Of the others, 10 highlighted needle use; 9 showed razor blades; 1 mother to child transmission, and 2 blood transfusions.

The age range of students attending the secondary school was 16–21 years. They can be assumed to have had more personal experience of sexual intercourse than most primary school children. Some of the males stated that they had used condoms, and asked specific questions about how to fit them properly. A long discussion took place in class about this, with the author drawing illustrations on the blackboard. shows some of the drawings submitted for the competition. The first one represents an unsafe injection being given, the second a man being infected by cutting his toe nails with a razor blade. The next two give an impression of conversations between couples about sex, and the last group depict the sexual act. The depiction of sexual intercourse from behind was said to show vaginal sex. All the students denied any knowledge or experience of anal sex, as indeed did everyone asked about it.

Conclusion: controlling HIV/AIDS

When people in Ezo county are asked how to control HIV/AIDS, the majority will begin by saying that sexual intercourse must be stopped or restricted to one partner. They know that this is the ‘correct’ response, but it is certainly not a complete one. For many of those interviewed, abstaining from sexual intercourse is impossible. It prevents pregnancy, which is something desired even by many very young women and their families. Also, the act itself is associated with well-being. Telling young men in particular to stop having sex is like telling them to act as if they are ill. It denies them a basic aspect of being alive, and comes close to suggesting that they stop eating. In the 1920s, Evans Pritchard found that a healthy Zande man who cannot demonstrate a readiness to have sexual intercourse as soon as he sees a woman's vagina was open to ridicule. That is still said to be the case. Older or educated men might like the idea of restricting sexual access to young women, but it may be suspected that they have their own motivations for doing so.

Apart from sexual contact, understandings about infection range from the use of sharp objects and blood transfusions to sharing water, kissing and urinating in the same place. For several of those interviewed there are a wide range of dangers, not all of which are connected with blood contact. HIV/AIDS control messages about some of them reinforced broader concerns, and public health information about different diseases are conflated. However, miscommunications are only part of the story. Informants described an ever constant threat of infection, whereby the specific mechanism is almost arbitrary. The excessive highlighting of razor blades by so many respondents is connected with such a perception. As has been noted, concerns about them being left on paths to deliberately infect passers-by suggest that they can have the properties of bad magic. They are also used in treatments by local healers, including oracles/diviners. They are imbued with associations that move beyond or envelop the realm of empirical and biomedical causality.

At one level, everyone, including the local healers themselves, will talk about ‘echive’ or ‘sida’ as if it is a disease with an aetiology recognized by formal health care workers. But that aetiology exists in a context and has limitations. It does not explain why sexual intercourse, which is something that all healthy adults should do, can be harmful for certain individuals, but not others, or why one razor blade is harmful but another is benign. Witchcraft, sorcery and magic retain their explanatory powers for HIV/AIDS, as they do for other afflictions, and with respect to HIV/AIDS there is an additional factor. An HIV positive person has characteristics that are similar to those of a witch or a sorcerer, in that he or she looks like everyone else, but is secretly killing them. The alarm that is expressed about the disease reflects unease that witches are everywhere. This helps explain why certain HIV positive individuals are so public about their condition, and why they become so closely connected with the Christian churches. It also sheds light on some of the specific alternative measures for HIV/AIDS control that are proposed in response to the question ‘how should the spread of HIV/AIDS be stopped in our community?’