ABSTRACT

This paper examines digital mobilisation with respect to knowledge production, legitimacy and power in Sudan since new communication and surveillance technologies became widespread. Enthusiasm for digital opposition peaked with the Arab Spring and troughed through the repressive government apparatus. Social media (SMS, Facebook, Twitter) and crowdsourcing technologies can threaten the government’s control over the public sphere as participatory practices. To arrive at this finding, we argue the significance of epistemological tools of those who control the representation of digital power, and approach state legitimacy as an ongoing and fragile process of constructing “reality” that requires continuous work to stabilise and uphold. At the same time, the paper describes an international counterpublic of security researchers and hackers who revealed that the Sudanese government invested greatly in controlling the digital landscape. We analyse Nafeer, a local grass-roots initiative for flood-disaster-relief that made use of digital media despite the digital suppression. Nafeer’s challenge to the state came from the way it threatened the state-monopoly over knowledge, revealing both the fragility and the power of state legitimacy.

Social media is widely thought to have been inseparable from the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions of 2011, yet the role of digital activism in overthrowing governments remains highly debated.Footnote1 Social media can help mobilise people around a common purpose. This has doubtlessly changed the scope of revolutions as well as wider activities to support citizen engagement and oversight including elections monitoring, constitution-making processes, and human rights and crisis reporting.Footnote2 Digital media have introduced new tools and techniques for the politically engaged to gather and share information, potentially altering the balance of power. However, governments also vie for control through new digital technologies, justifying this control as “anti-terror measures” in, for example, the United States and Germany, or as part of an “anti-western” morality in Sudan. Furthermore, the quest for surveillance and digital control is under scrutiny by a “counterpublic” of surveillance researchers and political hackers, which reveal details about governments’ digital capabilities. Governments are aware of the potential subversive power of social media, co-opting it in order to secure and hold onto power.Footnote3 Social media (SMS, Facebook, and Twitter) and crowdsourcing technologies facilitate participatory and discursive practices of producing evidence and shaping the official narrative by enabling people to engage in different representations of reality. Legitimacy is concerned with control over knowledge and social media use is perceived to threaten this control.

This paper examines knowledge production, legitimacy and power in the Sudan in the last decade since digital mobilisation became widespread. The enthusiasm for digital opposition peaked in parallel with the rise of the Arab Spring, then troughed through the repressive apparatus of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). Sudan’s investment in a digital upgrade of that apparatus, through hacking software, web monitoring devices and a governmental “Cyber-Jihad” unit, was partly responsible for this decline. Additionally, the government has used a moral discourse against digital technologies and tried to silence and appropriate alternative movements to stabilise its legitimacy.

In examining knowledge production and digital publics in Sudan, we move away from technological determinist-thinking implicit in an “open source” ideology that emphasises the liberating potential of social media as a means to counter state control or any hierarchical or hegemonic order. The argument made is that representations of technological control are powerful. Moving away from conceptions of knowledge as repressive techniques of powerFootnote4 residing in hierarchies and elites,Footnote5 we approach state legitimacy as an ongoing and fragile process of constructing “reality”, which requires continuous work to stabilise and uphold.Footnote6 Digital practices then consist of the ways people use technology towards both the ongoing workings and the contestations of power in gathering and sharing politically-engaged information.

Drawing on participant observations and interviews carried out by both authors between 2010 and 2015 in SudanFootnote7, this paper explores the digital capabilities of the Sudanese government as they were revealed by political hackers and security researchers. We illustrate how digital infrastructure reinforces the public imagination of state power and the state’s imagined threat of counterpublics by describing the NCP’s digital actions and how they resulted in bloggers and digital activists going off-line between 2011 and 2013. Our exemplary case is Nafeer, a grass-roots initiative that made use of digital media despite the history of digital suppression. It was widely praised for its use of digital media in the 2013 flood-disaster-relief, hailed as an example of citizen mobilisation, and a parallel “market of information” that seemed to counter state legitimacy. We argue that Nafeer’s digital success had to do with tedious practical work. Following Latour,Footnote8 technical mediation revealed the representational practices of the various actors involved (NCP, field volunteers, fundraisers, digital engineers and international players), as digital technologies mapped onto the grassroots architecture of a long-existing social form, the work group, and the networks of trust and organisation that came with it. Nafeer was indeed powerful in the sense of “getting things done”; this was possible through strong interpersonal networks and skilled volunteers who maintained the “actionable information” in a strategic way that kept the information close to the ground. Its challenge to the state came through the ways digital communication and information tools challenged a state monopoly over knowledge. Technologies seemed to threaten knowledge control. Thus, we conclude by asserting digital “publics” do not causally spring from digital media, but materialise as they provide for the creation and circulation of alternative visions of social order.

In the next section, we outline our conceptualisations of counterpublics, knowledge production and state legitimacy, and digital communications. Then we review the recent history of Sudan’s digital apparatus, its hardware and how it is used as a mechanism of suppression and violence. Lastly, we investigate the case of Nafeer and discuss its broader implications.

Conceptualising counterpublics as knowledge and power

Digital media has been euphorically promoted by observers as a hope for a better life, a cure-all for Africa’s problems by promoting information transparency, truth and justice. With interactive possibilities of internet 1.0 and 2.0, there were widespread assumptions of development,Footnote9 democracyFootnote10 and improved living conditionsFootnote11 among scholars and practitioners alike. While scholarship has become more nuanced and critical, such assumptions continue among humanitarian practitioners, such as the belief that “transparency breeds self-correcting behavior”Footnote12 and that accountability mechanisms improve government responses to crises. Recently, mass analysis of user-generated content, Big Data, is seen as an “intelligent tool that can help combat poverty, crime, and pollution.”Footnote13 CherletFootnote14 calls beliefs about technology and its purported outcome a form of “epistemic determinism”. In this thinking, people are facilely united into an interactive dialogue and possibly a shared purpose as a public or a counterpublic through the open and participatory capacities of new technologies such as Bernal described for Eritrea.Footnote15 However, understanding the role of digital media requires embedding them in a political context in which they can threaten and also bolster governments’ legitimacies.

Interactive platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and UshahidiFootnote16 enable publics, defined in the sense of an open space for dialogue, rather than in the HabermasianFootnote17 sense of “public sphere” as rational communication for finding consensus. Transported into the digital realm, this view of publics retains the criteria of being autonomous from the state and market, and capable of critical, reflexive and inclusive discussion.Footnote18 Depending on the platform, people can participate in varying degrees and forms. Content is structured by both the technology used to collect and represent information, and by what people do with the data, for example, editing, aggregating or ranking them. Even though the content is “open”, technology shapes representations of knowledge, emphasising, framing and erasing some data over others. Our conception of publics and counterpublics derives from this interplay of technology and people. We refer to both publics and counterpublics in order to draw attention to multiple technological and discursive arenas, some which subvert or challenge dominant discourses.Footnote19 We take the view that digital publics and counterpublics form in the selecting, shaping and framing of knowledge that is made possible by a digitally-linked collective, thereby emphasising the representational, semiotic “truth-constructing” dimension.

To study techno-social processes of forging publics in Sudan, we draw from the concept of “technological translation” as developed in Science and Technology Studies (STS) literature.Footnote20 STS uses “translation” to understand the transformation of things, people and/or information through mediation, invention and creation.Footnote21 Translation occurs at the level of representation. It involves a change in what is translated and the translator: a change of use, users and technologies themselves. A new “form emerges that did not previously exist”.Footnote22 We contend that knowledge through digital tools emerges through translations, and can be used in different ways according to epistemologies of the actors and institutions that generate and control it.

Following from this, governments’ interest in self-preservation and legitimacy is potentially challenged by digital media. Any attempt to form counterpublics in Sudan, whether politically motivated or not, challenges the government’s almost total monopoly over knowledge dissemination. Governments that build their legitimacy on fear, compliance and obedience are threatened by new information flows. Analysing Soviet dictatorships, philosophers Fehér, Heller and Márkus defined a “social order [as] legitimated if at least one part of the population acknowledges it as exemplary and binding and the other part does not confront the existing social order with the image of an alternative one as equally exemplary.”Footnote23 Our case considers how new social mass media undermine state legitimacy by altering normative standardsFootnote24 and producing an alternative social order. They offer new access to education,Footnote25 and undermine and alter beliefsFootnote26 and the meaning of symbols,Footnote27 important elements of legitimacy. This understanding of legitimacy locates it within the arena of representation, the outcome of performative and symbolic work, and an image of institutional “reality” that is take-for-granted as the status quo.Footnote28

Counterpublics engendered by digital technologies can threaten ruling hegemonies, since they question not only the means of coercion, but “the acceptance (even if fragmentary and not fully conscious) of the rulers’ definitions of reality by the ruled”.Footnote29 This threat is not limited to counterpublics within a national frame. Hackers, security researchers, and leaks that expose the proliferation of surveillance technologies form a transnational counterpublic reveal the double standard of governments’ moralities. This can show how governments compromise their own standards, be it privacy-related or concerning their political stance.

The Sudanese government, similar to other governments, actively controls local and transnational counterpublics, discussed further below. Technologies’ potential to enable digital publics must be considered in its socio-political and cultural context, where power and representation are tied to how actors use technologies and how technologies shape knowledge. Both the power of digital counterpublics and the legitimacy of the government are fragile.

Sudan’s digital landscape: the government and digital mobilisation

Sudanese digital activism is embedded in global and local politics. It is subject to sanctions and surveillance from the Sudanese government. It is also constrained by a US-embargoFootnote30 on the import and export of goods to and from Sudan since 1997, due to an alleged connection with so-called terrorist activity. US sanctions directed at the Sudanese government inadvertently reinforce Sudan’s oppressive and controlled media policy of its own people.Footnote31 Until 2014, residents in Sudan could not download or update American software for personal use, leaving operating systems unprotected and vulnerable. These sanctions were partially lifted in 2014, and further in 2018, and companies such as Google and even NASA situationally have by-passed sanctions.

Despite restrictions, Sudan went from less than 1% internet use by individuals in 2000 to 22.7% in 2013. Almost 30% of people can access the internet at home. With over 27 million mobile phone subscriptionsFootnote32 in a population of 37 million, digital access by ordinary people has grown exponentially. Regional movements, such as the separation of South Sudan and the political fate of Darfur and South Kordofan, were heavily debated on popular websites such as Sudanese Online, Sudan Vision, Sudan Tribune and Facebook. Civil society groups, local CBOs and NGOs have set up websites and Facebook pages. According to Glade,Footnote33 writing about youth activism, these purportedly “apolitical, [and] social justice oriented volunteer initiatives will likely be more important for Sudanese politics and society” than overtly political groups. They have similar social networks, built up skills through ties with the diaspora and forged alliances with other groups in the opposition, making it possible to “maintain activities in a productive manner that could connect with governance”.Footnote34 Despite their overtly apolitical stance, the existence of such networks and the effect of creating an alternative social order are treated as a threat to the government’s legitimacy. In parallel with a growing digital capacity in civil society, the government has upgraded its technical capabilities to control political activists’ internet use, exert oppression and instil fear, and interfere with volunteer activities.

The technical capabilities of Sudan’s government

An important aspect of the political context for social media use in Sudan is the government’s investment in its technical capabilities. The Sudanese National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) controls digital media use through multiple strategies, including blocking, controlling, jamming and slowing down certain websites, and hacking private accounts. NISS acquired ProxySG-servers from the US company Blue Coat, which enable governments and corporations to intercept internet traffic. Software also comes from the Italian software company Hacking Team, which enables access to private devices, including access to data, camera, and microphones. Soft- and hardware purchases contravene US sanctions and the Wassenaar ArrangementFootnote35 for the non-proliferation of dual-use software.

ProxySG allows controlling, restricting and intercepting private information, including encrypted (via SSL/https) information, such as that used to access bank accounts and private emails. This technology is used in Sudan “in conjunction with another Blue Coat technology called WebFilter [which conducts mass-surveillance filtered by categories]. The categories range from uncontroversial categories like ‘malicious sources’ and ‘spam’ to topics like ‘alternative spirituality/belief’ or ‘religion’.”Footnote36 Further, ProxySG can slow downFootnote37 particular websites (including https), potentially and subtly guiding people away from information provided on the slowed websites.Footnote38

The scientists named the report revealing Sudan’s acquisition of Blue Coat’s ProxySG, “Some devices wander by mistake”. We question this “mistake”. Cooperation between the CIA and the Sudanese security forces has long been suspected, brought to attention by the Los Angeles Times in 2005.Footnote39 The CIA reportedly brought Salah Gosh, the chief of Sudanese security forces to the US for cooperation. In 2010, the Washington Post wrote that despite “a genocidal track record” and Sudan being classified as a “terrorist state, […] the CIA is continuing to train and equip Sudan’s intelligence service in the name of fighting terrorism”.Footnote40 Citing a former security officer serving in Sudan, the article went on to quote: “‘There have also been transfers of equipment’ to the NISS, he said, ‘computers, etcetera’”.Footnote41

Despite such digital capabilities, Sudanese security cannot be seen as unified politically. It is divided and not all instances of government have access to such means of surveillance. Some dissidents have been tracked by the government, while others have been asked about Facebook passwords.Footnote42 Questions remain as to whether the Sudanese government is in control of these servers. Edward Snowden’s documents state that X-KEYSCORE, a US National Security Agency (NSA) programme has a server in Sudan. X-KEYSCORE can monitor “‘nearly everything a typical user does on the internet’, including the content of emails, websites visited and searches, as well as their metadata [up to] ‘real-time’ interception of an individual’s internet activity.”Footnote43

Still, it appears clear that some software was acquired by NISS from Hacking Team.Footnote44 A 480 GB data leak from Hacking Team orchestrated by hacker Phineas Phisher revealed Hacking Team had received the first payment from NISS in 2012 for software called Remote Control Services (RCS).Footnote45 RCS remotely installs spying software on targeted devices and records conversations through messenger services such as Skype, and copies cookies and passwords from Internet Explorer, Firefox, Thunderbird, Windows Live Mail, Outlook, Chrome and Opera. It also follows mouse movements, records keystrokes, accesses camera and microphones, and obtains geolocations via the Wifi-interface scanning for other routers.Footnote46 This information about ProxySG, X-KEYSCORE, and RCS indicates the varied and complex ways that governments control and infiltrate digital devices.

Technosocial consequences

In addition to technological means, the Sudanese government uses a discourse of morality. The context and history in Sudan has shaped how the government (and activists) engage in technosocial politics surrounding digitally-enabled communications. For example, the Sudanese government’s use of rhetoric of Islam in the interest of national security to control its citizens from moral infractions can be dated to 1989. Couched in shari’a law, the NCP “controls” and “defends” the morality of the Sudanese people through Islamic legal and disciplinary measures such as the Criminal Code of 1991. With the advent of social media, which not only came from this “West”, but appealed largely to youth, the NCP initiated a public discourse of immorality and fear attached to socials media. Before Facebook, text-messaging was disparaged as the cause of sexually-promiscuous youth.Footnote47 Public announcements issued by the ulama religious authority urged parents to monitor their children’s communications. The National Telecommunications Corporation established a hotline for parents to report on concerns about new media.

The government also more actively has used the internet to intercept people. In early 2011, the NCP formed a “Cyber Jihad” unit with around 200 fulltime employeesFootnote48 to monitor dissent groups’ communications on Facebook and to sabotage online protest movements. The Cyber Jihad Unit, trained in Malaysia and India, was used to hack accounts and track the growing number of Bloggers (from 70 to 300 in 2012) in Sudan.Footnote49 Efforts to control information have manifested in the use of physical violence.

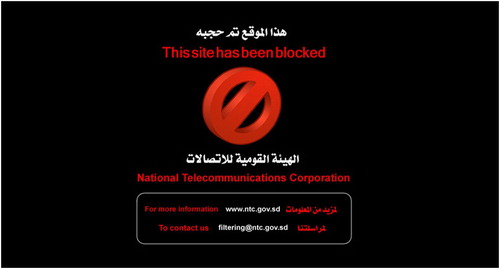

In one incident on 30 January 2011, the Cyber Jihad allegedly staged a fake demonstration known as “Protesting Youth for Change”. According to interviews an estimated 100 protestors were “arrested even before the demonstration started”,Footnote50 detained for 10–20 days, and allegedly tortured. In September 2013, according to Amnesty International at least 200 people were killed by police in a popular protest against rising bread and petrol prices.Footnote51 According to an interview with an IT activist and blogger,Footnote52 this signalled a new and more deadly approach to dissent from the ruling NCP. Whether true or false, across interviewees who participated in this opposition, there was a shared sense of certainty that protest equalled death. NISS thus appears to combine “older” techniques of oppression and fear mongering with newer digital technologies to control citizens. The government does not hide its efforts to control and modify the internet. In 2011, the following image was provided by the government when opening blocked websites ().Footnote53

In 2014, the government announced it would “double its efforts to filter […] negative websites […] ‘containing pornographic materials’ or those promoting ‘drugs, weapons, alcohol, gambling and insults against Islam.’”Footnote54 The internet is controlled in Sudan, and government opponents are aware, but do not know the extent of it. This image is an easy way to spread the threat of control and rumours of internet censorship: “The government employs a huge number of Chinese to monitor the internet in Sudan,”Footnote55 we were told. It was widely rumoured that the government not only blocked connections – which is a much easier process – but also monitored their secure (https/SSL) connections. From its access to surveillance technologies to its Cyber Jihad Unit to its concern for dissident content, the Sudanese government has a multi-level approach to sustaining its legitimacy and the current social order, attempting to thwart the construction of an alternative vision by hindering communication and morally stigmatisation. It stigmatises new technologies as immoral, a discourse used even against apolitical movements.

Nafeer

The case of Nafeer offers insight into how the Sudanese government has sought to control the shaping of truth and knowledge, even in response to movements with a purportedly apolitical mobilisation. The government first opposed the movement and later attempted to appropriate it. Nafeer mobilised around a natural disaster. Personal interviews with volunteers revealed the intention of the volunteers was not a digital opposition per se, however, the government efforts to control Nafeer led to its politicisation. This resulted in a representation of a counterpublic, an artefactual product of technology, increasingly perceived as a threat to government legitimacy.

Nafeer as a work group

In late summer of 2013, during the rainy season, the Nile overflowed its banks, a usual occurrence for that time of year. This time the amount of water was catastrophic, submerging a number of low-lying neighbourhoods in Khartoum, displacing or affecting around 180,000 peopleFootnote56 by the third week of rain. The government denied there was a serious emergency and stagnated on issuing permission to UNOCHA and other aid agencies to provide relief, even appearing on TV to reproach people for building houses close to the river. A local and independent youth initiative called Nafeer, meaning “trumpet” or “call to work” in Arabic, organised in response. A nafeer as a work group is a long-standing social institution in northern Sudan. Community work groups spring up around a variety of needs, predominantly agriculture, such as weeding fields or harvesting crops, but also cleaning houses or digging a well.Footnote57 It is a cultural institution that is not anchored to a specific private or communal purpose, and relies on an ideology of mutual support and solidarity. In agriculture, it is organised around existing social groups, such as patrilineal or affinal kin, neighbours or religious groups. Participants work on rotation, providing spontaneous labour when needed. They are initiated by the party needing the service, who serves as the temporary headman. This status dissolves after the nafeer concludes its work. It often is accompanied by slaughtering an animal for feasting, oral poetry and music. It relies heavily on trust, premised upon mutual reciprocity and voluntary action.

Initially Nafeer, organised through digital media such as Facebook (see ),Footnote58 was not vastly different from other apolitical charity initiatives set up by youth activists in Khartoum. It was symbolically represented by the hands of its Facebook profile in the colours of the Sudanese flag, shown above, and the government more or less tolerated and sometimes even supported Nafeer. Groups existed before and during the rise of digital activism, raising funds for a children’s cancer hospital, cleaning a park next to the Nile, or renovating a school, all with an open and participatory model.Footnote59 Nafeer appropriated digital tools to realise a work group to provide flood relief. A young software engineer, Abeer Khairy, designed the initial Ushahidi map that was used. She and others were involved in other community-based initiatives for social change, also based on an open source concept. The original volunteer group consisted of 70 members, who were connected through existing social networks. Initially, the Ushahidi map was used to publish the location of flooded areas to NGOsFootnote60 and information about collapsed buildings and sewage-contaminated water. Nafeer set up their operations in the offices of a local NGO to channel crowd-sourced funds, and use their computers and internet. It differed from a customary nafeer in that it did not have a “closed” structure based in expectations of reciprocity, but an “open” one that integrated activists based on skills and forged trust among them. In order to organise a large volunteer base, it needed a command structure. To quote again from Glade:

[…] the core leadership created a series of committees focused on various tasks—planning, health, and environment, volunteer training, and surveys make up a few. These committees were generally led by older members who had experience in the fields discussed; indeed, the group tended to defer to experience […]. At the same time, the policies instituted rarely came from the top. Rather, Nafeer encouraged a deliberative democratic process of decision making in which experienced volunteers created the standards.Footnote61

Nafeer as a network

During the relief effort, Nafeer’s volunteer base exploded to around 8,000 volunteers, with an estimated 2,000–3,000 volunteers working regularly.Footnote63 The original volunteers were involved in the activist movements described above, as well as more overtly political groups, such as Change Now and Girifna.Footnote64 This enabled them to mobilise a larger, networked support system based on social media links. As Vokes and Pype, and Pype observe,Footnote65 media enhanced networks or “contacts” are critical in African contexts for mobilising support for occasional and varied purposes. In Sudan, such is indeed the case as was shown for text messaging among youth.Footnote66

This opened channels that could be used to source information and money from the public at large and through transnational networks. Nafeer set up multiple FacebookFootnote67 and Twitter pages and also a hotline to which even the government emergency (Civil Defence Hotline) calls were routed since Nafeer was mobilising aid more quickly than the government. While content could be sent via Facebook, the network was made accessible to a broader off-line public through the hotline. Phoned-in reports of need were translated into maps of highly affected areas, which were used by supply distribution teams who delivered plastic shelters, food, drinking water and medical supplies. Volunteers also communicated needs from more peripheral areas to the centre through the Nafeer App, a smartphone app survey that used GIS, LBS and VAS technologies to report location and request services.Footnote68 Also, individual reports outside such areas were posted on Facebook and Twitter so that anyone nearby could respond according to the ethos of community support that Nafeer promoted. As Nafeer’s map designer Khairy said in an interview, “Just having a platform of data is not engaging enough”; it must be open and participatory.Footnote69

Most often, these technologies were used for internal communication among the volunteers. The network grew but the work remained goal-oriented and practical. International links became necessary to enable the use of technologies that were not available in Sudan due to US software sanctions. At the centre of operations, a table with phones was set up to translate incoming reports into spreadsheets of data, to then be inputted into Ushahidi. Ushahidi was limited because it provided only a cluster map and not pattern recognition. To make data useful, it had to be mined: data needed to be analysed with Google Earth or GIS. The Ushahidi map also could not show the extent of the flooded areas, contrasting with a satellite map, and proved less useful than manual ad-hoc problem solving.

Nafeer was in contact with the blogger Helena Puig Larrauri, a former Sudan United Nations Development Program (UNDP) employee, who put them in touch with UNDP. UNDP in turn had access to NASA satellite maps through a charter for major disasters. They sent images to Nafeer via email. Data sourced from incoming phone calls in the form of an excel spreadsheet were forwarded to a Standby Task Force volunteer in Scotland, who had access to Google Earth. Standby Task Force is a global digital volunteer network that provides distant support for crowdsourcing, mapping, and analysis.Footnote70 This volunteer translated data into a pie chart, and then layered the data and density of phone calls onto satellite maps. He spoke no Arabic and had to patch together information using Google Translate to yield pie charts and statistics that could then be sent back in a pdf format to Nafeer. The pie chart analysed need, a person’s location, damage, and specific items such as clothes, mosquito nets and plastic sheets that were targeted to places.

Actionable data thus required a network of volunteers who were linked with several other NGOs and community initiatives, with diaspora networks channelling money, as well as international aid agencies, UNDP and NASA, and the digital volunteer in Scotland. This made for a complex assemblage of personnel, technologies, knowledge and money. As one volunteer described it: “It was chaos, a table with a bunch of laptops on it, a pile of donated clothes in a corner, a huddle of people talking in another corner, [one of the organisers] dictating over the people on laptops.”Footnote71

Initially, it seems difficult to label this work group - turned into a network of highly interdependent and interpersonal links - a public, defined as a forum for open participatory communication. It was an open network system in its personnel, but it was also closed in the sense that much of the practical work of collecting, classifying and mining data happened through “older” technologies, specifically email, Microsoft Excel and Adobe, with manual remediation of content in turn making it useful. Also, while Nafeer had multiple Facebook pages, it soon abandoned its public page and relied on the private groups for organising. Examining how information was managed through its chain of actors, we found information was often confined to closed circles and designed for immediate hands on action.

Digital Nafeer as semiotic object

While Nafeer’s activities were executed primarily through closed networks, other events unfolded that placed Nafeer in a more public spotlight. In a parallel technological translation, Nafeer made headlines as a civil initiative. Facebook was instrumental in creating this image. As of August 2016, the English version of Nafeer’s website had 7,320 “likes” while the Arabic version had 65,135 “likes”. A public, when defined as a discursive space for open dialogue and knowledge production, pertains more closely to the intermedial enthusiasm that arose about Nafeer than a feature of Nafeer itself. The practical activities of Nafeer informed the mass-mediatised and deliberative aspects which translated Nafeer into a semiotic object, a “chronotope of media” as defined by Vokes and Pype.Footnote72 A chronotope is semiotic model, which brings “together new configurations of people, space, time, dreams, desires and beliefs”, and evokes new forms of personhood and communities. Digital Nafeer was a narrative for action, indexing an ethos of broad participation, community support and empowered persons in the past, and new hope for the future.

Nafeer was widely praised in the media for its coordinated and efficient disaster response when the government failed.Footnote73 The New York Times depicted the volunteer team as it would a streamlined corporate office.Footnote74 Humanitarian organisations such as UNOCHA and academics in the diaspora also commended Nafeer for its success. Bashri wrote about it as a fifth estate, a “vast and robust media landscape”Footnote75 and parallel “market of information” bypassing traditional media outlets, in order to “share unfiltered information without being hindered by political or editorial constraints”.Footnote76 She concluded Nafeer was able to mobilise an alternative public sphere through its use of ICTs, or, for those offline, through a trickle-down effect, that is, non-digitised networks.

While early on Nafeer was a networked coalition, ultimately this movement was drawn from different parts of society and was described as an initiative that managed to bridge social boundaries. GladeFootnote77 argues that Nafeer, which at first relied heavily on Facebook, grew along networks of people in similar socio-economic spheres, but over time appealed to a broader coalition of people through word of mouth, and across traditional social spheres. A report about Nafeer on national Blue Nile television station broadened awareness of it through mass media. Also, although Nafeer was perceived as anti-government, it was open and many of its volunteers were in fact supportive of the ruling NCP. Nafeer’s apolitical stance meant that it could coordinate with some parts of the government such as the Ministry of Health.Footnote78 The discursive space that emerged from Nafeer’s activities was highly contingent on mass media, and participants in these wider discussions could join the volunteer force that was inclusive of, but not defined by, social media.

The growing threat of Nafeer

Nafeer’s success in providing humanitarian relief, while initially a practical convenience for the government, soon became an embarrassment in the representational sense. When Nafeer began mobilising funds, the NCP “forced” all NGOs to contribute financially. At the same time, the NCP falsely accused Nafeer of holding onto crowdfunded donations and vilified it for its transnational links. The epistemological assumptions of Open Knowledge are not supported even when communication appears apolitical. “Open” when applied to a public crisis means a risk of alternative narratives of what has happened. At this level, the aerial view of a crowdmap combined with satellite imagery and Facebook content posed a threat to long-standing epistemologies over knowledge production and control, by a paternal and paranoid state.

When denouncing Nafeer failed to garner public support, the NCP attempted to co-opt its activities. When Nafeer was in full swing delivering supplies to affected neighbourhoods, the NCP forced Nafeer’s volunteers to wear pro-NCP t-shirts bearing the party image and to use government trucks for aid delivery. This backfired. Popular anger against the government for its early inaction resulted in incidents in which volunteers were attacked for having worn NCP t-shirts, appearing as government employees. The government’s Humanitarian Affairs Commission then sought to institutionalise Nafeer’s ad-hoc volunteer network into an organisation that could be monitored and subjected to government control, but Nafeer was not interested. Rather, the network dissolved when the crisis subsided.

The government’s various reactions suggest its perceived threat was not because Nafeer was overtly political or because of the use of digital technology to create a participatory initiative. Nafeer’s image as a counterpublic challenged the NCP’s legitimacy because it transcended controllable circuits of knowledge. The name Nafeer was previously used for hailing a counterpublic – Nafeer is the name of a Nuba diaspora newsletter that promoted a discourse of “resistance” and “survival” in opposition to the government.

Nafeer exposed the government’s fragile hold over knowledge production and information dissemination. Certain features of this image of a counterpublic made this more acute: visibility, community ownership, transparency and time stability. First, although the map was abandoned early on, data from marginalised areas was visually mapped and displayed online. This exposed neighbourhoods ignored by the government. Second, the somewhat amorphous, decentralised and reflexive structure of the group, not to mention its exponential growth in the size of its volunteer networks, made it hard to control as a tangible unit. This worked against the command structure promoted by the state, through nepotism and patronage. Third, the process was highly transparent and accountable. At first, reports were posted on Facebook and Twitter as well as called in. On Facebook, volunteers, in return, posted photos and regular budget updates, which helped donors to trust that money would be used for its intended purposes. Lastly, Nafeer dissolved after the crisis. Its personnel, map, network and infrastructure were disbanded but it left nonetheless a powerful capacity for mobilising and a fixed image of citizen empowerment in people’s minds. It exposed the NCP’s fragile hold over the crisis, thereby upsetting epistemological norms for the production of knowledge. Following the trend since the Arab Spring, as detailed above, there is an epistemic culture emerging through digital activism that builds on Sudanese social solidarity institutions, which does not depend on the state, but which the state is grappling to keep under its control.

The development of a government-backed initiative known as the “Renaissance of North Kordofan” supports this observation.Footnote79 Ahmed Haroun, indicted for war crimes by the ICC and governor of North Kordofan at the time of writing, initiated a development project in 2013 to revitalise infrastructures and institutions for foreign investment in which local “participation” would be prioritised and informally promoted as a nafeer.Footnote80 Mahé considers it a semantic strategy of inclusiveness and coerciveness on the part of the Kordofan authorities to evoke a “certain state of mind” for the “good” of the community.Footnote81 It might serve as a means for the government to assert seemingly benevolent intentions by appealing to a customary institution that is designed to benefit the poor (i.e. those who cannot hire labour), and exploiting, co-opting and even taxing it in the interest of a higher calling of the common good.Footnote82

Inadvertently, Nafeer, as a network of volunteers mobilising for relief, revealed and contested certain power dynamics. Digital Nafeer challenged the NCP’s monopoly over information and capacity to harness the power of the crowd. This was possible through the use of different communication technologies – private Facebook pages, mobile apps, mapping software and an ad-hoc network of volunteers – in contrast to the glorification of Nafeer as a counterpublic in the mass media.

Conclusion

The control exercised by the Sudanese state, combined with challenges to and reactions by the state with Nafeer, illustrate the potential for digital technologies to forge new spaces for interaction and information in Sudan. As we have argued, the perceived threat to this edifice of knowledge, the NCP’s measures to counteract this threat, and counter-measures to the NCP can be seen as struggles over representation. As Gal and Woolard argued about publics: “such representational processes are crucial aspects of power, figuring among the means for establishing inequality, imposing social hierarchy, and mobilizing political action”.Footnote83 We illustrated two empirical cases that threatened Sudan’s purported legitimacy, defined as the control over knowledge, symbols, representation of power through violent and suppressive means.

The example of Nafeer aptly illustrated how digital technologies enabled the movement to mobilise faster and more efficiently than the government, threatening its monopoly over knowledge and inadvertently exposing its fragile hold on legitimacy. Nafeer was made famous in part because of its original Ushahidi map, which was popularised as a testimonial to the government’s neglect and questioned the government’s version of “reality”. Yet, this original Ushahidi map proved less helpful in generating actionable data, revealing a gap between the purpose of technology and how local actors engaged with it. Inclusion was based on networks of skilled and connected people who knew how to use social media platforms, and on trust and personal security. Nafeer worked in part because social media technologies evoked the chronotope of an older architecture of relationships and knowledge structures. Nafeer effectively connected its core group with the broader ideology of solidarity. The argument that comes from this is that the power of technology is enabled by humans, and their imagination, hope, expectations and fears about what technology does for them. Our discussion of Sudan’s technical and political infrastructure in Sudan helped to situate Nafeer’s reaction to government interference. This is because of the history of suppression, and the fear and power that is related to technosocial interactions.

We showed that on the one hand, governments are purchasing and exchanging surveillance technology. In the quest for security, they even do this over borders of perceived ideological differences, cutting across their own policies. In order to uphold its monopoly over knowledge and to maintain its legitimacy, the Sudanese government combines its technological capabilities with actual violence such as arrest and torture, a morality discourse, and threatens digital counterpublics which in turn support self-censorship, digital abstinence and emigration.

By examining what actors do with technologies, we have revealed their epistemological concerns and interests, which may run counter to expectations. That the CIA shares security technology with the state contradicts Google’s sharing privacy and security technology with civil society. The NCP’s use of monitoring software to root out terrorists suggests the capacity to also use it for repressive purposes on its own people. Digital mobilisations must be carefully managed in Sudan, or risk both closure and individual persecution. The core epistemological assumption of open-source and open-knowledge is the idea that aggregated data or the “aerial view” of a situation is more transparent and trustworthy than linear, networked knowledge. The aerial view provided by satellite maps from NASA presented the NCP with a challenge not only to their capacity to see from a sovereign viewpoint, but also because such knowledge came from machinery and images over that of trusted and known sources. This is extremely important in Sudan, where knowing is contingent on the source of information through trust, history and proof. As we relayed, the NCP plays off this cultural feature as it exploits discourses of morality and fear surrounding new media.

As much as digital publics and counterpublics are heavily constrained within the repressive Sudanese context, the cases reveal that their absence is not a given, considering the work involved in upholding legitimacy. Both state legitimacy, and counterpublics that challenge it, are constructed and ordered representations made to cohere as “reality” through the production and contestation of a legitimate order. This work revealed the fragility of this “reality” and the struggle over knowledge production posed by new digital technologies.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks goes to all participants of the Digital Publics and Counterpublics workshop on 9–10 September 2016, especially to the organisers Sharath Srinivasan, Stephanie Diepeveen and George Karekwaivanane, and to the anonymous reviewers and the main editors of this journal for their thoughtful comments. We further thank the MPI for Social Anthropology and the LOST colloquium in Halle (Saale), Germany for the conducive environment of exchange and input at different stages of writing. Our gratitude goes to the interviewees who entrusted us with their information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Gladwell, Malcolm. “Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted.” The New Yorker, 2010.

2 Meier, “Building Egypt 2.0”; Bernal, Nation as Network; Pintak, Lawrence. “Crowd-Sourcing Tunisia: Separating Electronic Rumor from Reality.” The Seattle Times, 2011. http://old.seattletimes.com/html/opinion/2014000628_guest23pintak.html.

3 Matveeva, “Conflict Cure or Curse?”; Future Tense, “Netizen Report”; Chaos Computer Club. “Gutachten für NSA-BND-Untersuchungsausschuss: BND-Operationsgebiet Inland.” Gutachten. Chaos Computer Club e. V., October 6, 2016. https://www.ccc.de/de/updates/2016/operationsgebiet-inland.

4 Foucault, Discipline and Punish.

5 Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power.

6 Boltanski, On Critique.

7 About 18–24 months fieldwork in Sudan by each researcher. While our research was not focussed on this topic, both authors collected relevant stories, interviews and information. We further gathered and analysed publicly available information after hacks that completed the picture. In order to increase anonymization, we decided to limit information about our methodology.

8 Latour, “On Technical Mediation.”

9 Langmia, “The Role of ICTs in the Economic Development of Africa,” 146.

10 Chadwick, “Web 2.0,” 10.

11 Gates, “Billgate’s Letter.”

12 Bott and Young, “The Role of Crowdsourcing for Better Governance in International Development,” 49.

13 Anderson and Rainie, “Main Findings,” 16.

14 Cherlet, “Epistemic and Technological Determinism in Development Aid.”

15 Bernal, Nation as Network.

16 Okolloh, “Ushahidi, or’testimony’.”

17 Habermas, The Structural Transformation.

18 Postill, “Digital Politics and Political Engagement,” 167.

19 Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere.”

20 Callon, “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation”; Latour, “On Technical Mediation”; Star and Griesemer, “Institutional Ecology, Translations’ and Boundary Objects”; Czarniawska-Joerges and Sevón, Global Ideas; Rottenburg, Far-Fetched Facts.

21 Latour, “On Technical Mediation,” 32.

22 Rottenburg, Far-Fetched Facts, xxxi.

23 Fehér, Heller, and Márkus, Dictatorship over Needs, 137.

24 Barker, Political Legitimacy and the State; Suchman, “Managing Legitimacy,” 574.

25 Bourdieu, Sur l’État.

26 Weber, Economy and Society, 213.

27 Berger and Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality, 110.

28 Boltanski, On Critique, xi, 54.

29 Kubik, The Power of Symbols against the Symbols of Power, 12.

30 OFAC, Sudan Sanctions Program.

31 Kehl, Danielle, Tim Maurer, and Jacob Brogan. “Time to Rethink Tech Sanctions Against Sudan.” Slate, January 30, 2014. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2014/01/sudan_sanctions_are_keeping_secure_communications_tools_from_activists.html.

32 ITU, “Statistics.”

33 “Social Activism and Transnational Networks: Nafeer and Sudanese Flood Relief,” 35–36.

34 Ibid.

35 The Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies.

36 cf. Marquis-Boire et al., “Some Devices Wander by Mistake - Planet Blue Coat Redux,” 4 and 7.

37 Reporters Without Borders, “Ennemis d’Internet - Iran.”

38 “China: Electronic Great Wall Getting Taller | Enemies of the Internet.” http://12mars.rsf.org/2014-en/2014/03/10/china-electronic-great-wall-getting-taller/. Accessed May 27, 2015.

39 Silverstein, Ken. “Official Pariah Sudan Valuable to America’s War on Terrorism.” Los Angeles Times, April 29, 2005. http://articles.latimes.com/print/2005/apr/29/world/fg-sudan29.

40 Stein, Jeff. “SpyTalk - CIA Training Sudan’s Spies as Obama Officials Fight over Policy.” The Washington Post, August 30, 2010. http://voices.washingtonpost.com/spy-talk/2010/08/cia_training_sudans_spies_as_o.html.

41 Ibid.

42 Interviews with eight anonymous sources, Khartoum, Sudan, March 5–20, 2011.

43 Greenwald, Green. “NSA X-KEYSCORE Server Sites.” The Guardian, July 31, 2013. http://cryptome.org/2013/08/nsa-x-keyscore-servers.htm.

44 Nakashima, Ellen. “Report: Web Monitoring Devices Made by U.S. Firm Blue Coat Detected in Iran, Sudan.” The Washington Post, July 8, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/report-web-monitoring-devices-made-by-us-firm-blue-coat-detected-in-iran-sudan/2013/07/08/09877ad6-e7cf-11e2-a301-ea5a8116d211_story.html.

45 Marczak et al., “Mapping Hacking Team’s ‘Untraceable’ Spyware.”

46 Cano, “Government Grade Malware.”

47 Lamoureaux, Message in a Mobile.

48 Freedom House, “Sudan | Freedom on the Net 2013,” 8.

49 Reporters without Borders, “Sudan.”

50 Interview with second anonymous source, Khartoum, Sudan, March 6, 2011.

51 Amnesty International, “Sudan Escalates Mass Arrests of Activists amid Protest Crackdown.”

52 Usamah. “Usamah Mohamed.” http://usamahmohamed.blogspot.com/. Accessed October 17, 2016.

53 Sureau's screenshot, see also: Sudan Tribune. “Sudan Steps up Measures to Block ‘Negative’ Websites - Sudan Tribune: Plural News and Views on Sudan.” March 25, 2014. http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article50432

54 Ibid.

55 Interview with third anonymous source, Khartoum, Sudan, March 5, 2011.

56 UNOCHA, “Sudan.”

57 Mahé, “A Tradition Co-opted.”

58 “Nafeer.” https://www.facebook.com/gabaileid/. Accessed September 2, 2016.

59 “Madrasatna - انتسردم .” https://www.facebook.com/Madrasatna/. Accessed January 20, 2017; “Our Environment, Our Responsibility- Let’s Clean Sunut Forest!” https://www.facebook.com/groups/letscleansunutforest/. Accessed January 20, 2017.

60 Sperber, Amanda. “Abeer Khairy, The Woman Behind The Khartoum Flood Map”, The Daily Beast, 2013. http://www.thedailybeast.com/witw/articles/2013/08/15/the-woman-behind-the-khartoum-flood-map.html.

61 Glade, “Social Activism and Transnational Networks”, 42.

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.

64 Supposedly many Nafeer people were involved into the Sudanese “Shadow Government”, a more governance-oriented group that mirrors the current government, with “shadow ministers” who make decisions.

65 Vokes and Pype, “Chronotopes of Media in Sub-Saharan Africa”; Pype, The Making of the Pentecostal Melodrama, 90–95.

66 Lamoureaux, Message in a Mobile.

67 Six Nafeer Facebook groups exist: Public (English); Public (Arabic); Closed Volunteers, historical data, communications team.

68 Abdelmoneim, Mobile application in disaster management.

69 Khairy, Abeer. Nafeer, February 27, 2014.

70 “Standby Task Force | A Humanitarian Link between the Digital World and Disaster Response.” http://www.standbytaskforce.org/. Accessed October 17, 2016.

71 Interview with anonymous source, Khartoum, Sudan, March 12, 2015.

72 Vokes and Pype, “Chronotopes of Media in Sub-Saharan Africa,” 4.

73 Hilali, Mohamed. “Sudanese Citizens Accuse Government of Negligence after Floods.” The Niles, 2013. http://www.theniles.org/en/articles/society/1998/.

74 Kushkush, Isma’il. “As Floods Ravage Sudan, Young Volunteers Revive a Tradition of Aid.” The New York Times, August 29, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/30/world/africa/as-floods-ravage-sudan-young-volunteers-revive-a-tradition-of-aid.html.

75 Bashri, “The Use of ICTs”, 81.

76 Ibid, 76.

77 Glade, “Social Activism and Transnational Networks”.

78 Ibid.

79 Mahé, “A Tradition Co-opted,” 236.

80 Ibid, 235–236.

81 Ibid, 239–240.

82 Ibid, 240–241.

83 Gal and Woolard, “Constructing Languages and Publics”, 129.

Bibliography

- Abdelmoneim, Lana. “Mobile application in disaster management.” February 18, 2015.

- Amnesty International. “Sudan Escalates Mass Arrests of Activists amid Protest Crackdown.” Amnesty International USA, 2013. http://www.amnestyusa.org/news/news-item/sudan-escalates-mass-arrests-of-activists-amid-protest-crackdown.

- Anderson, Janna Quitney, and Lee Rainie. “Main Findings: Influence of Big Data in 2020.” Future of the Internet. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2012. http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/07/20/main-findings-influence-of-big-data-in-2020/.

- Barker, Rodney S. Political Legitimacy and the State. Oxford, New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Bashri, Maha. “The Use of ICTs and Mobilisation in the Age of Parallel Media–an Emerging Fifth Estate? A Case Study of Nafeer’s Flood Campaign in the Sudan.” Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies 35, no. 2 (2014): 75–91. doi: 10.1080/02560054.2014.922111

- Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor Books, 1990.

- Bernal, Victoria. Nation as Network: Diaspora, Cyberspace, and Citizenship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- Boltanski, Luc. On Critique: A Sociology of Emancipation. Cambridge: Polity, 2011.

- Bott, Maja, and Gregor Young. “The Role of Crowdsourcing for Better Governance in International Development.” Praxis: The Fletcher Journal of Human Security 27, no. 1 (2012): 47–70.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Reprinted. Cambridge [u.a.]: Polity Press, 1999.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Sur l’État: Cours Au Collège de France, 1989-1992. Edited by Patrick Champagne, Remi Lenoir, Franck Poupeau, and Marie-Christine Rivière. Cours et Travaux. Paris: Raisons d’agir: Seuil, 2012.

- Callon, Michel. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St. Brieuc Bay.” Power, Action, and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge 32 (1986): 196–223.

- Cano, Nick. “Government Grade Malware: A Look at HackingTeam’s RAT.” Bromium Labs (blog), July 10, 2015. http://labs.bromium.com/2015/07/10/government-grade-malware-a-look-at-hackingteams-rat/.

- Chadwick, Andrew. “Web 2.0: New Challenges for the Study of e-Democracy in an Era of Informational Exuberance.” I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society 5 (2008–2009): 9–41.

- Cherlet, Jan. “Epistemic and Technological Determinism in Development Aid.” Science, Technology & Human Values 39, no. 6 (2014): 773–794. doi: 10.1177/0162243913516806

- Czarniawska-Joerges, Barbara, and Guje Sevón. Global Ideas: How Ideas, Objects and Practices Travel in a Global Economy. Vol. 13. Malmö: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2005.

- Fehér, Ferenc, Agnes Heller, and György Márkus. Dictatorship Over Needs: An Analysis of Soviet Societies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1983.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Fraser, Nancy. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” Social Text, no. 25/26 (1990): 56–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/466240.

- Freedom House. “Sudan | Freedom on the Net 2013.” Freedom on the Net. Sudan | Freedom House. Accessed May 22, 2015. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2013/sudan#.VV79GEZUz9q.

- Future Tense. “Netizen Report: Turkish Leaders Disagree on Social Media Blocking.” Slate, March 12, 2014. http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2014/03/12/netizen_report_turkish_leaders_disagree_on_whether_to_block_social_media.html.

- Gal, Susan, and Kathrvn A. Woolard. “Constructing Languages and Publics: Authority and Representation.” Pragmatics 5, no. 2 (1995): 129–138. doi: 10.1075/prag.5.2.01gal

- Gates, Bill. “Billgate’s Letter.” Thailand the big picture. Information Technology Projects in Thailand. March 18, 1998. http://www.nectec.or.th/it-projects/billg-letter.html.

- Glade, Rebecca. “Social Activism and Transnational Networks: Nafeer and Sudanese Flood Relief.” Sudan Studies Association Bulletin 33, no. 1 (2015): 35–47.

- Habermas, Juergen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge Mass: MIT Press, 1962.

- ITU. “Statistics.” International Telecommunication Union. Accessed October 17, 2016. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx.

- Kubik, Jan. The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

- Lamoureaux, Siri. Message in a Mobile: Mixed Messages, Tales of Missing and Mobile Communities at the University of Khartoum. Bamenda, Leiden: Langaa, African Studies Centre, 2010.

- Langmia, Kehbuma. “The Role of ICTs in the Economic Development of Africa: The Case of South Africa.” International Journal of Education and Development Using ICT 2, no. 4 (2006): 144–156.

- Latour, Bruno. “On Technical Mediation.” Common Knowledge 3, no. 2 (1994): 29–64.

- Mahé, Anne-Laure. “A Tradition Co-Opted: Participatory Development and Authoritarian Rule in Sudan.” Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 51, no. 2 (2018): 233–52. doi:10.1017/S0008423917000993.

- Marczak, Bill, Claudio Guarnieri, Morgan Marquis-Boire, and John Scott-Railton. “Mapping Hacking Team’s ‘Untraceable’ Spyware.” Interdisciplinary laboratory based at the Munk School of Global Affairs. The Citizen Lab (blog), February 17, 2014. https://citizenlab.org/2014/02/mapping-hacking-teams-untraceable-spyware/.

- Marquis-Boire, Morgan, Collin Anderson, Jakub Dalek, Sarah McKune, and John Scott-Railton. “Some Devices Wander by Mistake - Planet Blue Coat Redux.” University of Toronto: Citizen Lab and Canada Centre for Global Security Studies, July 9, 2013.

- Matveeva, Anna. “Conflict Cure or Curse? Information and Communicaiton Technologies in Kyrgyzstan.” In New Technology and the Prevention of Violence and Conflict, edited by Francesco Mancini, 56–71. New York: International Peace Institute, 2013.

- Meier, Patrick. “Building Egypt 2.0: When Institutions Fail, Crowdsourcing Surges.” IRevolutions (blog), April 19, 2012. https://irevolutions.org/2012/04/19/crowdsourcing-egypt-2-0/.

- OFAC. Sudan Sanctions Program (1997). https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/sudan.pdf.

- Okolloh, Ory. “Ushahidi, or’testimony’: Web 2.0 Tools for Crowdsourcing Crisis Information.” Participatory Learning and Action 59, no. 1 (2009): 65–70.

- Postill, John. “Digital Politics and Political Engagement.” In Digital Anthropology, edited by Heather A. Horst and Daniel Miller, 165–184. London & New York: Berg Publishers, 2013. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9KuPzBgus7oC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=digital+politics+and+political+engagement+2012+postill&ots=uAeWHnUKD8&sig=OHzbQf41jppq2mmWSSxTf2wQJ3c.

- Pype, Katrien. The Making of the Pentecostal Melodrama: Religion, Media and Gender in Kinshasa. Anthropology of the Media, v. 6. New York: Berghahn Books, 2012.

- Reporters Without Borders. “Ennemis d’Internet - Iran.” http://en.rsf.org/internet-enemie-iran,39777.html. Accessed May 27, 2015.

- Reporters without Borders. “Sudan: Scoring High in Censorship.” Enemies of the Internet (blog), March 10, 2014. http://12mars.rsf.org/2014-en/2014/03/10/29/.

- Rottenburg, Richard. Far-Fetched Facts: A Parable of Development Aid-Inside Technology. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2009.

- Star, Susan Leigh, and James R. Griesemer. “Institutional Ecology,Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39.” Social Studies of Science 19, no. 3 (1989): 387–420. doi: 10.1177/030631289019003001

- Suchman, Mark C. “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches.” The Academy of Management Review 20, no. 3 (July 1, 1995): 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788 doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331

- The wassenaar arrangement on export controls for conventional arms and dual-use goods and technologies list of dual-use goods and technologies and munitions list (2015).

- UNOCHA. “Sudan: Hundreds of Thousands Affected by Heavy Rains and Floods | OCHA,” 2013. http://www.unocha.org/top-stories/all-stories/sudan-hundreds-thousands-affected-heavy-rains-and-floods.

- Vokes, Richard, and Katrien Pype. “Chronotopes of Media in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Ethnos 83, no. 2 (2016): 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2016.1168467.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1978. http://archive.org/details/MaxWeberEconomyAndSociety.