ABSTRACT

This article presents a linguistic landscape analysis of pictures taken in Eritrea’s capital Asmara between 2001 and 2018, stemming from the respective periods of Italian, British, Ethiopian and Eritrean rule. The analysis illustrates how these semiotic signs, fossilized as well as contemporary, bear witness of the ways in which language and state ideologies of the country’s respective rulers were symbolically implemented and enshrined in visible language. Next to Italian, Amharic, Tigrinya and Arabic, attention is given to English, the international language that was introduced during the British Protectorate period and managed to maintain and strengthen its position in Asmara in recent years in relation to the inhabitants’ connection to the internet as a means to virtually escape from the city. Central in the analysis is the notion of public space as a multilayered socially constructed phenomenon showing the imprints of societal happenings. Such traces of history in Asmara contribute to changing concrete places into spaces and as such help memorizing and handing over the narratives connected to them as reflections of historical and contemporary language policies that over the years have co-constructed and given meaning to Asmara’s public space.

This article is about the linguistic landscape of Asmara, capital of Eritrea, and the ways in which it reflects the historical development of language policies in Eritrea, enacted by the foreign powers that ruled the country and by the government of the State of Eritrea after Independence. Before going into an analysis of concrete examples of semiotic signs in Asmara, I first discuss the notion of public space as a multilayered socially constructed phenomenon and connect it to the concept of a “guilty landscape” referring to the impact or – literally – the imprint of societal happenings on the physical surroundings where they took place. Such imprints or traces of history contribute to changing concrete places into spaces and as such help memorizing and handing over the narratives connected to these spaces. After that I will introduce the sociolinguistic tradition of linguistic landscaping as a means to unravel the traces and reflections of historical and contemporary language policies that over the years have co-constructed and have given meaning to Asmara’s public space. Then I move on to analyze a (limited) collection of pictures, taken in Asmara between 2001 and 2018, as semiotic signs stemming from the respective periods of Italian, British, Ethiopian and Eritrean rule. I mainly try to show how public signs in Asmara, fossilized as well as contemporary, bear witness of the ways in which language and state ideologies of the country’s respective rulers were symbolically implemented and enshrined in visible language. In addition to Italian, Amharic, Tigrinya and Arabic, attention is also given to English, the international language that was introduced during the British Protectorate period and that managed to maintain and, contrary to what one would expect, even strengthen its position in Asmara in recent years in relation to its inhabitants’ connection to the internet as a possibility to virtually escape from the city. In the final section the different historical periods under investigation are comparatively discussed and some general conclusions are drawn pertaining to the meaning of Asmara’s consecutive linguistic landscapes as socially constructed spaces.

Public space and its semiotics

Asmara, the capital city of Eritrea, is located on the northern tip of the Ethiopian Plateau at an altitude of 2,325 meters. Its city limits contain a land area equal to 45 square kilometers with an estimated population 804,000 in 2017. It lies on the Eritrean Railway and is a major road junction; its international airport is 4 kilometers southeast and Massawa, its port on the Red Sea is 65 km northeast. Its climate is Mediterranean with an annual average of 520 millimeters of precipitation.

Public space is hardly ever neutral. It is invested with meaning, as emerging from the assemblage of historical events, memories and narratives reflecting these events, often handed down over generations. Let me illustrate this with an example. Tiananmen Square in Beijing for many visitors no doubt evokes the image of the lonely Chinese citizen standing in front of a series of tanks and apparently blocking their movement during the Tiananmen Square protests on 4 June 1989. This iconic picture that became known as Tank Man – and has been long banned from Chinese cyberspace – led to the creation of multiple memes by Chinese internet users, incorporating images ranging from yellow rubber ducks, Legos and Angry Birds as tanks or simply showing the empty road with neither tanks nor man.Footnote3 All these images deliver the message that is contained in the original picture. As such Tank Man still defines our image of Tiananmen Square as a public space, the meaning of which is closely connected to the dictatorship of the Chinese government. Even without any visible reference to the 1989 protests, Tiananmen Square as a semiotic landscape, can be “read” as having been part of a historically meaningful event.

One could even refer to Tiananmen Square as a “guilty landscape” or even a “terrorscape.” The term “guilty landscape” was introduced by the Dutch artist and writer Armando in the 1970s.Footnote4 Armando used this concept to metaphorically “capture the kind of guilt that attaches to a landscape – now silent, flourishing and beautiful – that has witnessed terrible events in the past.”Footnote5 Writers on the Holocaust and other atrocities, as for example the genocide in Rwanda and Srebrenica in 1994 and 1995,Footnote6 have stipulated the necessity of “keeping the memory of atrocity alive.”Footnote7 A “terrorscape” can be conceptualized as a place “where terror, political or state-perpetrated violence had happened or was prepared.”Footnote8 As such, terrorscapes are “spaces and places but also landscapes or simply segments of spatial environments that play a role in the shared reminiscences of a community.”Footnote9 Such places share a “high density of historical traces”Footnote10 and these traces are the main ingredient for constructing the narratives that keep their memory alive.

Such “traces” can take different forms, ranging from mere imprints left by historical events to real man-made material signs that can be found in public space and date back to the times in which these events happened. In addition to memorials, statues, buildings images and other artifacts, also language can be considered a semiotic sign through which meaning can be attributed to a specific place and a narrative of that place can be constructed and maintained. Language in the sense of speech, i.e. spoken language, without any voice recording, is not really a permanent characteristic of a historical or contemporary place. In order to construct a local narrative we have to turn to visible traces of language, i.e. language engraved or carved in stone, wood or metal, painted or drawn on doors, fences or walls or printed or stamped on a variety of information carriers like billboards, advertisements, leaflets, posters, stickers and signs. This ensemble of visible language, often in multimodal connection with illustrations, icons, colors or emoticons is referred to as the linguistic or semiotic landscape of a given locality.

Linguistic landscaping

Linguistic landscaping is the sociolinguistic study of visible traces of language in public places.Footnote11 Only in recent years have linguists and other social scientists turned their interest to “visible discursive phenomena in the public space,”Footnote12 meaning, as Blommaert put it, that

these days, sociolinguists do not just walk around the world carrying field notebooks and sound recording equipment; they also carry digital photo cameras with which they take snapshots of (…) “linguistic landscapes.”Footnote13

Most of the first-generation linguistic landscape studies are rather descriptive in nature. Blommaert, in his study of the linguistic landscape of his own neighborhood of Berchem, Antwerp, is among the first to plead for a more theoretically oriented and ethnographically informed approach. He considers linguistic landscaping as a quick and easy toolkit for detecting or diagnosing the major sociolinguistic features of an area. From this first diagnosis, one can then move into a more in-depth investigation of local sociolinguistic regimes and especially the forms and functions of literacy therein. Finally, linguistic landscaping can give a historical dimension to the sociolinguistic description of public spaces since it reflects earlier stages and historical developments of literacy use.Footnote16

Following Blommaert’s perspective on the historical dimension of linguistic landscaping and his plea for a not only descriptive but also more in-depth, analytical approach, in the following I will give a historical perspective on the linguistic landscape of Asmara. More specifically, I will deal with the way in which historical reflections of top-down language policies in Eritrea are (still) visible in Asmara’s physical space. According to Blommaert:

Physical space is also social, cultural and political space: a space that offers, enables, triggers, invites, prescribes, proscribes, polices or enforces certain patterns of social behavior; a space that is never a no-man’s-land, but always somebody’s space; a historical space, therefore, full of codes, expectations, norms and traditions; and a space of power controlled by, as well as controlling, people.Footnote17

Linguistic landscape analysis is typically based on pictures that document the visible use of language in a specific chronotopic context, i.e. in a specific place, be it a building, a street, a neighborhood, a city, a province or a country, at a specific time or historical period.Footnote18 Such pictures are preferably taken by the researcher who can then at the same time investigate the “emplacement”Footnote19 of the signs in their context and preferably also conduct ethnographic interviews with the senders (makers) and receivers (readers) of the signs under investigation. In this way the three “axes” or dimensions of signs in linguistic landscaping are dealt with: a backward axis, looking at the past, i.e. at the producers and the conditions of production of a sign; a forward axis, looking at the future, i.e. the intended audience and uptake of the sign; and a sideways axis, looking at the present, i.e. the content, location and emplacement of the sign in relation to its context and other signs.Footnote20

A historical or longitudinal linguistic landscape analysis as proposed here, in an ideal world would use pictures of semiotic signs that were taken in Asmara in the subsequent historical periods under investigation. In most cases however, and also in this case, such pictures cannot easily be found or are simply unavailable.Footnote21 I therefore had to make use of more recently collected data. These consisted of pictures that were taken by myself during my visits to Asmara in 2001 and 2005, by my Master students Debbie de Poorter and Marijke Vormeer in 2009 and my colleague Yonas Mesfun Asfaha between 2016 and 2018. Only in the 2018 case the pictures were explicitly taken with the intention to collect images of Asmara’s historical linguistic landscape reflecting the country’s language policies. Due to the specific type of (historical) data that were collected, it was impossible to include systematic and in-depth ethnographic interviewing as an additional method of data collection. What will be dealt with below therefore is a rather arbitrary and limited collection of pictures. These pictures however allow for a historical sociolinguistic analysis since they not only reflect contemporary language regimes but also contain traces of earlier episodes in which the political and sociolinguistic fabric of society looked totally different and the ensemble of languages in public space was a reflection of language policies in those specific historical periods. These specific episodes in the history of Eritrea include the period of Italian colonization (1889–1941), the British Protectorate (1941–1952), the Federation with Ethiopia (1952–1962), the period of Ethiopian annexation of Eritrea (1962–1991), and, since 1993, the independent State of Eritrea. By studying Asmara’s linguistic landscape in connection with the country’s diachronic top-down language policies,Footnote22 we can better understand the transformations that over the decades shaped Asmara’s image as a public space.

Reflections of language policies on the ground

My tourist gaze

Many of the pictures I took in Asmara in 2001 concentrated on touristic landscapes in and around the city. They show quite some historical cultural objects that I would consider to be semiotic signs that in their appearance and emplacement refer to specific periods or highlights in the history of Asmara and Eritrea. My tourist gaze made me include in my collection mainly landmark buildings from the period of Italian colonization such as the Fiat Tagliero petrol station (1938), Cinema Impero (1937), Kedesti Mariam Beite Kristian often cited as the Enda Mariam Orthodox Church (1938), the Al Kulafah Al Rashida Mosque (1938) and the even older Roman Catholic Cathedral of Our Lady of the Rosary (1923), showing (traces of) modernist Italian architecture and contributing to the city’s narrative and meaning as a public space in Italian colonial times, which lives on in the epithet “Asmara: Africa’s secret modernist city.”Footnote23 I also photographed more mundane objects: the city’s main shopping street Harnet Avenue, its covered and open-air markets and even a cycling race that passed through the streets of Asmara. Of a somewhat different nature were the pictures that I took of the Sandal MonumentFootnote24 on Shida Square, a giant pair of sculpted metal sandals symbolizing Eritrea’s tenacity that brought about Independence, the many posters and murals referring to the tenth anniversary of Eritrea’s Independence in 2001 and a painting in Asmara Palace Hotel near the airport showing a group of armed freedom fighters having a meal together – all referring to victory and independence. Although some of these pictures did contain text, they were certainly not taken with that intention.

Language diversity in Eritrea

Eritrea has nine officially recognized languages which are written in three different scripts and belong to three different language families. The names of these languages are in most cases identical to the ethnic groups that use them. Tigrinya, Tigre (both written in syllabic Ge’ez script) and the Arabic of the Rashaida ethnic group (written in consonantal Arabic script) are Semitic languages that belong to the larger Afro-Asian language family. Also Dahalik an oral language spoken in the Dahalik Archipelago in the Red Sea and for a long time considered a dialect of Tigre is a Semitic language.Footnote25 Afar, Saho, Bilen and Bidhayeet (previously referred to as Hidareb) are Cushitic languages that also belong to the Afro-Asian language family. They are all written in Latin alphabet. Kunama and Nara finally are Nilo-Saharan languages that are also written in Latin alphabet.Footnote26 All these languages, except for Dahalik, are used as languages of instruction and school subjects in primary education and they are also used in daily radio programs by the state broadcast media. Tigrinya, Tigre and Arabic are also used in newspapers and television programs. This relates to the country’s multilingual language policy that recognizes the equality of the languages and encourages their use.Footnote27 In addition to these Eritrean languages also English, as “a neutral language without a strong social or political base in Eritrea,”Footnote28 plays an important role as a language of instruction in educational settings, in international business and communication of public institutions and big commercial enterprises and multinationals.Footnote29

Especially the urban centers of Eritrea, like Asmara and Massawa, reflect the country’s diversity of languages and scripts in their linguistic landscapes where we see contemporary and historical printed street signs, names of businesses and public offices, and handwritten signs, announcements and graffiti on notice boards and walls in mainly Tigrinya, Arabic and English.Footnote30 Other Eritrean languages are hardly represented in the linguistic landscape of the country whereas Italian and Amharic are only represented to a limited extent, both connected to specific historical episodes and language regimes the city went through. My data, although limited, are therefore a reflection of old and new language policies that caused some languages to become visible and others to stay (nearly) invisible in public space. In addition to the above limitation, most of my data represent top-down signs. Such signs, because of their physical quality, simply survive longer in public space than often ephemeral bottom-up signs that are much more vulnerable for human activity or weather influences.

Italian rule

Even if it was not the first foreign power to rule Eritrea, it is mainly Italy that left its colonial footprint in the country. Eritrea became an Italian colony in 1890 with first Massawa and as of 1897 Asmara as its capital. In that period Italian was used as an official administrative language. The Italian period lasted until 1941 and gave rise to economic and infrastructural projects such as telephone services, roads and a railway system that certainly contributed to the country’s development.Footnote31 Under Italian rule the native population was however only allowed to attend four years of primary school where the curriculum was totally based on Italian geography, history, and culture. Italian was the only language of instruction and Tigrinya and Arabic could only be taught as a subject. Italian is still clearly visible in Asmara, not only in old signs from colonial times but also in newly made signs such as a text and an image on a garden fence of most probably an Italian resident of Asmara alerting the public to a not so friendly guard dog: Attenti al cane.Footnote32

is an illustration of the infrastructural activity of the Italian colonizer in Asmara. It shows a construction that is part of the Asmara Municipal Waterworks, Saracinesca Aquedotto Municipale Asmara, that were built by the Italians as early as 1916. Given the fact that the Asmara waterworks as part of the Italian municipal infrastructure were built by an Italian firm, it comes as no surprise that Italian is used to refer to the producers, the functionality and ownership of the construction. In terms of the three dimensions proposed for linguistic landscape analysis, I would suggest that the creator of this sign, the Italian colonial authority, did not necessarily have the ambition to inform native inhabitants of Asmara about the waterworks but simply left a mark of its presence and authority by using an acronym and Italian writing without expecting any referential uptake by an Eritrean audience.

The sign in can be found on the wall of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Rosary. It says Divieto di affisione and refers to the fact that any billposting is prohibited here. It differs from the information sign in in that the producer of the sign, the Italian authorities in Asmara, clearly mean to convey a very concrete meaning here, i.e. a prohibition. The reference to Article 663 of the C.P.C., the Italian Codice di Procedura Civile (Code of Civil Procedure) makes it clear that violation of this prohibition can lead to prosecution of the offender. The sign in other words assumes the audience to be literate in Italian and to know the law, which, in view of the restrictive educational policies under Italian colonial rule that only provided very limited Italian language education to native Eritreans, is certainly not self-evident.

Finally, the sign Ingresso above the two doors next to the main entrance of the Asmara Theatre and Opera House that was built in Harnet Avenue in the 1920s was most probably targeted at the Italian colonial elite and their local Eritrean entourage that in the 1930s must have frequented this temple of high culture (see ).

The traces in Asmara’s linguistic landscape dating back to Italian times as well as the semiotics of the omnipresent Italian architecture from the 1930s in the city, are clearly a reflection of a colonial period that might have contributed to Eritrea’s development but at the same time, by dominating the cityscape with Italian semiotics, leaves no doubt about who is in charge here. In this linguistic landscape Italian colonial power ruled, native Eritreans hardly counted, and the majority of the latter certainly did not or only passively participate in one-sided (Italian) literacy events and practices. This is also reflected in local newspapers at the time that can be considered moving, non-permanent, parts of the linguistic landscape. In 1890 and 1891 the Italian newspapers L’Eritreo and Corriere Eritreo were established by Italian colonists. A Tigrinya newspaper in those days was Melekete Selam, established by the Swedish Mission.Footnote33

British protectorate

After the Second World War, Eritrea – as a former Italian colony – temporarily came under British Mandate (1941–1952). English was then used as the main administrative language as can be seen from the almost iconic old yellow post box in that, in addition to its original name “Posting Box” in cast iron, also has a sign that, judging from its design and the way it is attached to the post box, was obviously added much later, informing the audience about the mail “[collecti]on hours.” In addition to introducing English as the language of education in all post-primary and higher education,Footnote34 British rule can also be credited for introducing the two major local languages Tigrinya and Arabic in basic education and newspapers.Footnote35 These languages were allegedly promoted because they could equally serve the Christian Tigrinya group, which approximately constituted half of the population and the other half being predominantly Muslim groups of which as a matter of fact only the Rashaida had Arabic as their first language. Unlike the other Eritrean languages, Tigrinya and Arabic moreover had a writing tradition that made them fit to be used in education.Footnote36 It is also suggested that the underlying British strategy for promoting Tigrinya and Arabic was “to inflame religious animosity between Christians and Moslems to the point that no unity among Eritreans seeking independence would become possible.”Footnote37

During the period of British Protectorate English became a language of prestige that next to Tigrinya and Arabic was clearly visible and well-respected in public space. In 1941 the Eritrean Weekly News was first published in English by the military administration, followed in 1943 with a Tigrinya (Semenawi Gazeta) and Arabic version.Footnote38 Also without ever having been an English colony, Eritrea seems to have accepted English as a post-colonial or rather international language. The language continued to exist under Ethiopian rule and it got an extra stimulus when at the end of the 1990s many foreigners came to the country. Today English seems to be less connected to foreigners or tourists but rather appears in Asmara’s linguistic landscape as a sign of participating in a globalized world (see also below).Footnote39

Federation with Ethiopia and annexation

As soon as the British realized that no easy solution was possible for an independent Eritrea, their authority was handed over to the United Nations and it was finally decided that Eritrea would be federated with Ethiopia. In the preparation phase of this federal union different suggestions of official languages were proposed and discussed in often heated debates. Tigrinya and Arabic were proposed as the languages of the Eritrean government and the other languages of Eritrea were accepted for public dealings with authorities, for use in religious and educational affairs and for expressing ideas.Footnote40 During the Federation (1952–1962) English stayed a language of prestige, social capital and education. At the same time Amharic, Ethiopia’s national language began to gain status at the expense of Tigrinya. Amharic was introduced in 1958 as a language of instruction in grades 1–4 of elementary education, replacing Tigrinya and Arabic.Footnote41 Ethiopia in 1962 abolished the federal union through a statement read to the members of the Eritrean Assembly in Amharic – “a language understood only by a handful of the 68-member body”Footnote42 – and made Eritrea its 14th province. Tigrinya and Arabic were suppressed and replaced by Amharic in official domains.Footnote43 The story goes that in 1963 Arabic and Tigrinya textbooks were publicly burnt.Footnote44 Although the place in the Asmara suburb where the incineration allegedly took place will probably not anymore show any traces of this tragedy, I consider the burning of books for political or ideological reasons the symbolic negation and physical destruction of the semiotic landscape represented by these books and the languages contained in them. Tigrinya and Arabic were altogether banned from public space and remained limited to the home environment and their speakers were made symbolically illiterate and voiceless.Footnote45

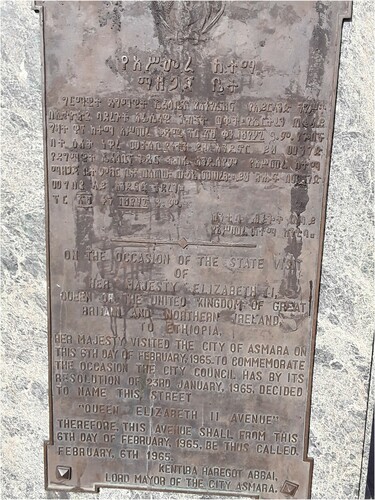

In the 1960s Amharic started to appear on buildings and signs in the streets of Asmara, mainly together with English. Examples are , showing a bus stop sign, , a plaquette commemorating the visit of Queen Elisabeth II to Asmara during the Haile Selassie reign on 6 February 1965 and , the Naval Technical Training Centre from the time of the Marxist-Leninist Derg regime that in 1974 overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie, all in Amharic and English with Amharic on top. In terms of language policy Haile Selassie and the Derg were very much alike. Amharization and Ethiopization prevailed but at the same time English was maintained as a teaching language in high schools and in commercial and public institutions. The main thing was that Amharic was ideologically pushed as a unifying language, for all of Ethiopia, i.e. including the annexed territory of Eritrea,Footnote46 aiming at “enforced assimilation and repression of culture.”Footnote47

These and other signs in Amharic and English that were produced by the Ethiopian authorities during the period of Ethiopian rule reflect the changing political constellation of Eritrea. Where once Italian was omnipresent as a colonial language, now Amharic took over as the self-declared national language. The number of signs in Amharic that nowadays can be found in Asmara however seems to be less than the ones in Italian and a closer inspection of the Amharic signs moreover shows clear traces of deterioration and erosion. As a matter of fact, many of the Amharic signs were erased or painted over as can be seen when the paint is fading over the years. Without the municipality taking specific measures, which for obvious political reasons is most probably not to be expected, in a few years most of these signs will not be readable anymore and these direct traces and reflections of the terrorscape of Ethiopian oppression, especially during the last years of Haile Selassie’s rule and the entire Derg period, will have largely disappeared from the streets and buildings of Asmara, without however losing the main narrative of the armed struggle against Ethiopia that is kept alive by for example murals depicting fighters and the yearly commemoration of Eritrea’s Independence, announced by printed posters and notes all over the city.

During the Ethiopian period (1962–1991) and especially the brutal Derg regime “the policies of ‘Ethiopianization’ and ‘Amharization’ intensified, the latter being one of the factors which awakened national consciousness and united diverse ethnic groups against the imperial regime.”Footnote48 In this period

newspapers appeared in Amharic, Tigrinya and Arabic, including the Unionist Party’s Ethiopiya and Hibret (Union), the Muslim League’s Voice of Eritrea in both Arabic and Tigrinya’ (…). By 1954, however, the Unionist government closed down its rivals including the Semenawi Gazeta. The official Il quotidiano eritreo, Zemen, and Ethiopiya continued. Hibret was revived in 1963 and remained Eritrea’s largest Tigrinya newspaper through 1990, when Ethiopia’s impending defeat at the hands of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) led to the collapse of the government-sanctioned papers.Footnote49

After independence – the state of Eritrea

In 1961, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) started an armed movement for the independence of Eritrea. This movement was later dominated by the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and after an intensive armed struggle of 30 years in 1991 the war ended and the EPLF formed a provisional government. In 1993 in a UN sponsored referendum the majority of Eritreans voted for independence from Ethiopia and the country was formally declared the sovereign State of Eritrea.

is a wall painting from the early 1990s reflecting the period of armed struggle. It shows the Eritrean fighters’ social life in the field. Note that the female fighter is mending her plastic sandals and the male fighter is cooking, reflecting the reversal of gender roles during the armed struggle. Paintings like this one, made on behalf of the government, illustrating episodes of the armed struggle and forming the building blocks for continued memory and narratives of Eritrea’s fight for freedom, have mostly disappeared from the semiotic landscape of Asmara over the years as a consequence of weather influences and neglect.Footnote50 Restoring and maintaining these memorials would certainly contribute to keeping the shared reminiscences of the people as an ingredient for constructing the narratives that keep their memory alive.

Already during the war for independence, the EPLF and ELF used Tigrinya and Arabic in their formal communication and publications.Footnote51 Already in those days the EPLF developed a language and education policy that considered all languages in Eritrea as equal and promoted their use in education and mass media. This policy became official in the 1991 policy document “Declaration of Policies on Education in Eritrea” in which the Provisional Government in order to “bridge up the linguistic and cultural gaps existing within our society” entitled all children in elementary education to take their schooling in their mother tongue.Footnote52 In addition to that, depending on certain conditions, Tigrigna and/or Arabic were to be used as languages of instruction and as compulsory subjects in the curriculum. The document also says that “following the completion of the elementary level […] the medium of instruction will be English” and that “other languages will also be taken up as subject matters.”Footnote53 Eritrea’s language policy was confirmed in the 1997 “Constitution of Eritrea” that stipulates that “the equality of all Eritrean languages is guaranteed.”Footnote54 The official declaration of a policy however, does not mean that it can or will also be realized in practice. In actual fact, Tigrinya and Arabic became languages of wider national communication and working languages of the government. Interactions of civil servants with the public and in-house communications of public offices were mainly conducted in Tigrinya and rules, regulations and proclamations from government offices were usually printed in Tigrinya, Arabic and English.Footnote55 Also the newspapers that were launched in 1992 by the Provisional Government of Eritrea were in Tigringya (Hadas Eritrea) and Arabic only (Eritrea Al-Hadisa). In addition, in 1992 the Ministry of Information published Eritrea Profile, an English language weekly.Footnote56

Language equality in education in other words did not imply equality for the languages used in society. Especially the written use of the Eritrean languages other than Tigrinya and Arabic, and English in public space is rather limited. Focusing on the linguistic landscape of Asmara we did not find any printed or written Saho, Nara, Afar, Bidawyeet, Tigre, Kunama or Bilin for that matter. Asmara might be the capital of a renowned multilingual country with a language policy focusing on unity through diversity, the languages that are used on signs from the post-independence era are in fact limited to Tigrinya, Arabic and English. In official public signs, such as name plates of ministries, other public institutions and street names, we generally see the fixed order of Tigrinya, Arabic and English reflecting Eritrea’s post-independence language policy. There are of course traces of “old” and “new” Italian (see above) and some odd Chinese, French or German but it is no doubt English that has been clearly conquering Asmara’s linguistic landscape. An example of an official trilingual Tigrinya, Arabic English sign is the name plate on the building of the Maekel Region Court in (Maekel being the region around Asmara) and the Harnet Avenue street sign in .

English not only appears in official trilingual signs in Asmara. More than 75% of all collected signs in and around Harnet Avenue, Asmara’s main shopping street, contain English and between 30% and 40% are English-only signs.Footnote57 This presence of English might be related to Eritrea’s recent diplomatic and political history when, after independence, foreign missions, aid agencies and multilateral organizations were opening offices in the capital, and, after the country’s border war with Ethiopia in 2000, also a contingent of UN peacekeepers came to Asmara.

As a consequence of the closure of the UN peacekeeping mission and subsequent diplomatic isolation of the country, the departure of some foreign missions, development aid agencies and NGOs, and the stagnation of tourism, the visibility of English might be expected to have declined.Footnote58 Upon closer inspection however in Harnet Avenue, in addition to “old” official English in trilingual signs and tourist English in restaurants and shops, nowadays also high visibility of contemporary commercial English is found, in connection mainly with the emergence of the Internet. The English displayed on these signs no longer seems to consist of mainly texts advertising computer hardware and software items a decade ago but also includes a growing number of international logos and icons of products like Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Google, Viber, Imo, Tango and Messenger that connect Asmara’s inhabitants to the outside world and their friends and relatives living in the Eritrean diaspora all over the world (see ).

As such the contemporary linguistic landscape of Asmara reflects that the country’s marginality and political isolation not necessarily prevent its inhabitants from digitally participating in globalization phenomena like the internet. Even if Eritrea is one of the world’s least connected countriesFootnote59 and the percentage of residents using the Internet – mainly via slow dial-up connections – according to the United Nations International Telecommunication UnionFootnote60 is only 1.08% (in 2015), the broad availability of affordable internet café’s in Asmara where the connectivity is certainly higher than in the rest of the country, supports this impression.Footnote61 The internet seems to be used as a way to escape the authorities’ strict control – most of the 13 private newspapers that were launched in Asmara in Tigrinya and Arabic after 1996 have been closed down in 2001 by the Ministry of InformationFootnote62 and English is perceived as “an important way of being part of that globalisation process and of lessening [the people’s] isolation.”Footnote63 In this way I would propose that also English can be considered part of a not so innocent or even guilty landscape by indirectly reflecting the limited physical, ideological and political freedom of Eritrea’s citizens in general and Asmara’s inhabitants in particular.

Conclusion

In this contribution I have tried to show by means of “horizontal archeology”Footnote64 how the periods of foreign rule and independence of Eritrea and their accompanying language policies have left clear traces in Eritrea’s capital of Asmara. I did so by looking at semiotic signs, mainly visible printed language, in public space. Before I proceed comparing these periods and drawing some conclusions, I want to refer to the naming history of downtown Asmara’s main street and show how the semiotics that are conveyed by the street’s name changed over the years and reflected the country’s respective rulers’ legacies.Footnote65 In the Italian period (1890–1945) the street was called Mussolini Avenue; in the British period (1941–1952) its name was Queen Victoria Avenue; during the Ethiopian Imperial period (1962–1974) it was called Godana Haile Selassie (Emperor Haile Selassie Avenue) and during the Derg period (1974–1991) its name was Beherawi (National Avenue). Only after Eritrea’s Independence in 1991 it was given its current name: Harnet Avenue (Godena Harenet/Independence Avenue). This overview in a nutshell represents the main argument in the above.

I hope to have shown that a historical, quasi longitudinal, approach to linguistic landscaping has the potential to unravel the representations of historically developing top-down language policies in semiotic signs placed in the streets of Asmara. By connecting these emplaced signs to their historical genesis and the aims of the authorities or powers that produced them, we could analyze these places as examples of a socially constructed space that contains the memory and narrative of languages and language policies from Italian times to contemporary Eritrea.

Looking at the period of Italian colonial rule, one might acknowledge the development and relative prosperity it brought to the country but at the same time one also has to realize that Asmara’s semiotic landscape became broadly Italianized, not only through its famous Italian architecture but also through the colonial government’s Italian public signs that conveyed an image and identity of Italian-ness, leaving out or even excluding the majority of all those native Eritreans who lacked any proficiency in Italian and as a consequence were voiceless outsiders rather than participants in their own city. As such the Italian footprint in Asmara is a one-sided and thoroughly colonial one that only came to an end because of Italy’s defeat in the Second World War.

During the British Protectorate after Italian rule mainly the groundwork was laid for a strong presence of English as an important language in Asmara’s public space. The British might have installed Tigrinya and Arabic as the country’s official languages and languages of education, according to some historians they mainly did so to prevent the Christian and Muslim groups in the country from uniting and claiming independence. English as an international, prestigious and well-respected language has been visible in Asmara’s linguistic landscape ever since.

During Ethiopian rule, first in a federal union and later as a province of Ethiopia, Eritrea was subjected to Ethiopianization and Amharization. Amharic was ideologically pushed as a unifying language for all of Ethiopia, including the annexed territory of Eritrea, entailing “enforced assimilation and repression of culture.”Footnote66 The burning of Tigrinya and Arabic books during Ethiopian occupation can be considered a linguistic landscape ex negativo, a “guilty landscape” or even “terrorscape.” English as a “neutral” international language was hardly touched by these developments.

After independence, the State of Eritrea established an official language policy of unity through diversity that had already been prepared by the EPLF during the period of armed struggle against Ethiopia. All Eritrean languages were declared equal and could be used as languages of instruction in elementary education. English became a language of instruction in post-elementary schooling and a subject at all levels of education. Tigrinya and Arabic also became school subjects for all students. The majority of public signs in the linguistic landscape of Asmara however is trilingual, using Tigrinya, Arabic and English. Other Eritrean languages are hardly seen in Asmara’s public space. Establishing a language policy of linguistic equality is apparently easier than actually putting this policy into practice. As such the linguistic landscape of Asmara might be multilingual but by using only two of the country’s languages plus English, it at the same time conveys the clear message that although all languages are declared equal in the Constitution, some are still more equal than others. One could in other words also consider the government’s “unity through diversity” slogan as a euphemism for the classical divide et impera, i.e. by declaring all languages equal, preventing the Muslim ethnic groups in Eritrea, constituting 50% of the population, from uniting as Muslims under the banner of Arabic and as such forming a real counter force to the population’s other 50% of Orthodox Christian Tigrinya speakers who play a major role in the country’s government.

As can be seen from the above, the semiotic landscape of Asmara is multilayered and complex. It synchronically offers its multiple diachronic meanings to contemporary audiences and observers. Depending on who these observers are, interpretation will take place. In this meaning making process, signs from the Italian era will most probably be read and interpreted as historical traces of a past political structure in which Italy ruled Asmara and policed its citizens in Italian. Those historical Italian signs will no longer be interpreted as having legal force and no citizen of Asmara will expect to be ever punished for breaking the Italian Codice di Procedura Civile when billposting in Harnet Avenue. Signs from Italian times are part of the Italian heritage and therefore mainly of interest for historians and tourists. In much the same way the Amharic signs in Asmara are seen as connected to a period of ruthless Ethiopian suppression that no longer exists and the signs of which are no longer meaningful as an instrument and reflection of Ethiopian power for Asmara’s citizens (and will soon disappear as a consequence of environmental influences and a lack of municipal maintenance). This is to say that the ensemble of signs one can find in the diachronically established linguistic landscape of Asmara will not easily be misinterpreted in synchrony by their audiences. They will rather be seen as what they are: some as historical traces of colonial times, others as repudiated reflections of oppression and struggle, and still others as relevant information for functioning as a citizen in contemporary Asmara – when for example looking for the Maekel Region Court in Sematat Avenue or wanting to find an Internet Café.

Let us now return to the concept of public space that I used in my analysis of the linguistic landscape of Asmara and that I initially described as a social, cultural and political entity that offers, triggers, prescribes certain policies and certain patterns of social behavior. I reiterate that public space is never neutral but always somebody’s historical space, and therefore full of codes, expectations, norms and traditions, a space of power controlled by, as well as controlling people. In a recent article, Simon Springer contributed to “re-theorizations of place as a relational assemblage, rather than as an isolated container.”Footnote67 Place, he argues “is not ‘the Other’ of space (…) it is not a pure construct of the local or a bounded realm of the particular in opposition to an overbearing, universal, and absolute global space.”Footnote68 Referring to Massey,Footnote69 space, according to Springer should be viewed

as the simultaneity of stories-so-far, and place as collections of these stories, articulations within the wider power-geometries of space. The production of space and place is accordingly the unremitting and forever unfinished product of competing discourses over what constitutes them.Footnote70

Applying this insight to the position of English in Asmara, we can conclude that throughout Eritrean history English has been a stable factor in Asmara’s linguistic landscape, be it as a stand-alone language during the Protectorate, in combination with Amharic during Ethiopian rule or in combination with Tigrinya and Arabic in recent years. In today’s Asmara, English, in addition to being a language of international affairs, business and tourism, also connects the city to the global internet as illustrated by the growing number of signs and advertisements referring to computer hardware and software, digital gadgets and online services available in shops and internet cafés. As such it offers Asmara’s inhabitants a digital lifeline to the outside world and indirectly at the same time reflects the repressive policies of the Eritrean government in matters of freedom of religion, speech and press, as a consequence of which thousands of Eritreans have left and are still leaving the country in search for freedom and a better future. In each historical episode dealt with in the above, the narrative of English – and all other languages for that matter – could always be understood as the result of “the stories-so-far,” as unfinished products of competing discourses over the linguistic landscape of Asmara as a constructed social space that is never neutral.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See e.g. https://www.britannica.com/place/Asmara; https://www.encyclopedia.com/places/africa/eritrea-political-geography/asmara; https://www.worldscapitalcities.com/capital-facts-for-asmara-eritrea/; http://www.nationalpedia.com/asmara-the-capital-city-of-eritrea/.

2 See https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/er.html; http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/eritrea/overview.

3 Du, Birth of Social Class, 97–103.

4 Reijnders, “Watching the Detectives,” 175; Van Alphen, Caught by History, 128.

5 Spaul and Wilbert, “Guilty Landscapes,” 86.

6 Van Alphen, Caught by History; Hoondert, “Srebrenica.”

7 Spaul and Wilbert, “Guilty Landscapes,” 87.

8 Van der Laarse, “Beyond Auschwitz,” cited in Mazzucchelli, van der Laarse, and Reijnen, “Traces of Terror,” 4.

9 Mazzucchelli, van der Laarse, and Reijnen, “Traces of Terror,” 3.

10 Ibid., 5.

11 Blommaert, Ethnography; Blommaert and Maly, “Ethnographic Linguistic Landscape.”

12 Juffermans, Local Languaging, 56.

13 Blommaert, Ethnography, 1.

14 Landri and Bourhis, “Linguistic Landscape,” 25.

15 Juffermans, Local Languaging; Wang, “Consuming English.”

16 Blommaert, Ethnography, 2–3.

17 Ibid., 3.

18 Wang and Kroon, “Chronotopes of Authenticity.”

19 Scollon and Wong Scollon, Discourse in Place.

20 Blommaert and Maly, “Ethnographic Linguistic Landscape,” 199–200.

21 An interesting source for longitudinal linguistic landscape studies could be printed collections of historical photographs and heritage picture postcards dealing with a specific locality; see e.g. the collection of pictures of Asmara from 1936–1937 on http://senato.archivioluce.it/senato-luce/scheda/foto/IL0600000637/8/Asmara.html?start=72&query=&jsonVal=.

22 Johnson, Language Policy.

23 Archer, “Asmara.”

24 I was informed that some years ago the Sandal Monument has been removed; in its place there is a small garden without any visible semiotic signs.

25 Idris, “Dahalik.”

26 Lewis, Simons, and Fennig, Languages of Eritrea.

27 Asfaha, Literacy Acquisition.

28 Woldemikael, “Language,” 123.

29 Kroon, Van der Aa, and Asfaha, “English in Asmara.”

30 Asfaha, Literacy Acquisition; Asfaha, “English Literacy.”

31 Hailemariam, Language and Education.

32 See also Vergari, “Italian in Asmara.”

33 Cornell and Killion, Historical Dictionary, 397. Since I did not do any research into Eritrean newspapers as part of the country’s linguistic landscape, I have to base myself here and in the following on Cornell and Killion, Historical Dictionary.

34 Wright, Ideologies and Methodologies.

35 Asfaha, Literacy Acquisition. According to Tekle Woldemikael (personal communication, July 2018) Tigrinya and Arabic were already used in this way in the Italian colonial period.

36 Hailemariam, Language and Education.

37 Tseggai, “History,” cited from Hailemariam, Language and Education, 85.

38 Cornell and Killion, Historical Dictionary, 397.

39 Kroon, Van der Aa, and Asfaha, “English in Asmara.”

40 Asfaha, Literacy Acquisition.

41 Tekle Woldemikael, personal communication, July 2018.

42 Haile, “Ethiopia-Eritrea Conflict,” 2.

43 Tseggai, “History.”

44 Bokru, “Eritrean Literary,” cited by Hailemariam, Language and Education, 85.

45 Collins, “Voice.”

46 Yonas Mesfun Asfaha, personal communication, May 2018.

47 Cliffe, “Forging a Nation,” cited by Akinola, “Politics and Identity,” 60.

48 Gottesman, Fight and Learn, cited by Asfaha, Literacy Acquisition, 17. In writing the above, I am fully aware that the final history of Eritrea, especially with respect to “the pursuit of Eritrean nation-making” as shown by Akinola (“Politics and Identity,” 48) is yet to be written.

49 Cornell and Killion, Historical Dictionary, 397. For an Ethiopian perspective see Reta, Quest for Press Freedom.

50 Yonas Mesfun Asfaha, personal communication, May 2018.

51 Woldemikael, “Language.”

52 Department of Education, Declaration of Policies, 3, cited by Hailemariam, Language and Education, 89.

53 Ibid., cited by Hailemariam, Language and Education, 90.

54 Constitution of Eritrea, 4, cited by Hailemariam, Language and Education, 92.

55 Kroon, Van der Aa, and Asfaha, “English in Asmara.”

56 Cornell and Killion, Historical Dictionary.

57 Vormeer, English Makes Us; De Poorter, Engels in Asmara; Asfaha, “English Literacy.”

58 Kroon, Van der Aa, and Asfaha, “English in Asmara.”

59 Groden, “World’s Worst Internet.”

60 See http://www.itu.int/net4/itu-d/icteye/, last accessed May 2018.

61 Hailemariam, Ogbay, and White, “English and Development.”

62 Cornell and Killion, Historical Dictionary.

63 Hailemariam, Ogbay, and White, “English and Development,” 16.

64 Quayson, Oxford Street, 4.

65 Tesfamariam, “100 Years.”

66 Cliffe, “Forging a Nation,” cited by Akinola, “Politics and Identity,” 60.

67 Springer, “Violence Sits in Places,” 90.

68 Ibid., 92.

69 Massey, For Space.

70 Springer, “Violence Sits in Places,” 93.

71 Ibid., 96–7.

Bibliography

- Akinola, O. A. “Politics and Identity Construction in Eritrean Studies, c. 1970–1991: The Making of the Voix Érythrée.” African Study Monographs 28, no. 2 (2007): 47–86.

- Archer, C. “Asmara: Africa’s Secret Modernist City.” 2006. https://www.wmf.org/sites/default/files/article/pdfs/pg_26-29_Asmara.pdf.

- Asfaha, Y. M. “English Literacy in Schools and Public Places in Multilingual Eritrea.” In Low-educated Adult Second Language and Literacy Acquisition, edited by I. van de Craats and J. Kurvers, 213–221. Utrecht: LOT Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics, 2009.

- Asfaha, Y. M. Literacy Acquisition in Multilingual Eritrea. A Comparative Study of Reading Across Languages and Scripts. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic, 2009.

- Blommaert, J., and I. Maly. “Ethnographic Linguistic Landscape Analysis and Social Change; a Case Study.” In Language and Superdiversity, edited by K. Arnaut, J. Blommaert, B. Rampton, and M. Spotti, 197–217. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Blommaert, J. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes. Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2013.

- Bokru, H. “A Short History of Eritrean Literary Tradition. (Tigrigna Version).” Journal of Eritrean Studies 3, no. 1 (1988): 30–39.

- Cliffe, L. “Forging a Nation: The Eritrean Experience.” Third World Quarterly 11, no. 4 (1989): 131–147.

- Collins, J. “Voice, Schooling, Inequality and Scale.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 44, no. 2 (2013): 205–210.

- Constitution of Eritrea. The Constitution of Eritrea. Ratified by the Constituent Assembly, on May 23, 1997.

- Cornell, D., and T. Killion. Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Langham: Scarecrow Press, 2011.

- De Poorter, D. “Engels in Asmara: Een analyse van het linguïstisch landschap van Harnet Avenue in Asmara, Eritrea.” [English in Asmara: An Analysis of the Linguistic Landscape of Harnet Avenue.] MA thesis, Tilburg University, 2016.

- Department of Education. Declaration of Policies on Education in Eritrea by the Provisional Government. Legal-Notice, Number 2. Asmara: The Provisional Government of Eritrea (EPLF), Department of Education, 1991.

- Du, C. “The Birth of Social Class Online. The Chinese Precariat on the Internet.” PhD thesis, Tilburg University, 2016.

- Gottesman, L. To Fight and Learn: The Praxis and Promise of Literacy in Eritrea’s Independence War. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press, 1998.

- Groden, C. “These Countries Have the World’s Worst Internet Access.” 2015. http://fortune.com/2015/10/06/worst-internet-access/.

- Haile, S. “Historical Background to the Ethiopia-Eritrea Conflict.” In The Long Struggle of Eritrea for Independence and Constructive Peace, edited by L. Cliffe and B. Davidson, 11–31. Nottingham: Spokesman, 1988.

- Hailemariam, C. Language and Education in Eritrea. A Case Study of Language Diversity, Policy and Practice. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic, 2002.

- Hailemariam, C., S. Ogbay, and G. White. “English and Development in Eritrea.” In Dreams and Realities: Developing Countries and the English Language. Paper 11, edited by H. Coleman. London: British Council, 2011.

- Hoondert, M. “Srebrenica: Conflict and Ritual Complexities.” In Cultural Practices of Victimhood, edited by M. Hoondert, P. Mutsaers, and W. Arfman, 19–38. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Idris, S. M. “Dahalik: An Endangered Language or a Tigre Variety?” Journal of Eritrean Studies 6, no. 1 (2012): 51–74.

- Johnson, D. C. Language Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Juffermans, K. Local Languaging, Literacy and Multilingualism in a West African Society. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2010.

- Kroon, S., J. Van der Aa, and Y. M. Asfaha. “English in Asmara as a Changing Reflection of Online Globalization.” In Language and Culture on the Margins: Global/Local Interactions, edited by S. Kroon and J. Swanenberg, 53–68. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Landri, A., and R. Y. Bourhis. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16, no. 1 (1997): 23–49.

- Lewis, M. P., G. F. Simons, and C. D. Fennig. Languages of Eritrea. 19th Edition Data. Texas: SIL International Online, 2016. http://www.ethnologue.com.

- Massey, D. For Space. London: Sage, 2005.

- Mazzucchelli, F., R. van der Laarse, and C. Reijnen. “Introduction. Traces of Terror, Signs of Trauma.” In Practices of (Re)presentation of Collective Memory in Space in Contemporary Europe, edited by R. van der Laarse, F. Mazzucchelli, and C. Reijnen, 3–19. Special Issue 119 of Versus. Quaderni di studi semiotici, 2014.

- Quayson, A. Oxford Street, Accra. City Life and the Itineraries of Transnationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

- Reijnders, S. “Watching the Detectives. Inside the Guilty Landscapes of Inspector Morse, Baantjer and Wallander.” European Journal of Communication 24, no. 2 (2009): 165–181.

- Reta, M. C. The Quest for Press Freedom: One Hundred Years of History of the Media in Ethiopia. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2013.

- Scollon, R., and S. Wong Scollon. Discourse in Place: Language in the Material World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Spaul, M., and C. Wilbert. “Guilty Landscapes and the Selective Reconstruction of the Past. Dedham Vale and the Murder in the Red Barn.” In Dark Tourism. Practice and Interpretation, edited by G. Hooper and J. J. Lennon, 83–95. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Springer, S. “Violence Sits in Places? Cultural Practice, Neoliberal Rationalism, and Virulent Imaginative Geographies.” Political Geography 30 (2011): 90–98.

- Tesfamariam, I. “100 Years on Asmara’s Main Street.” April 18, 2012. http://www.madote.com/2016/07/pictures-100-years-on-asmaras-main.html.

- Tseggai, A. “The History of the Eritrean Struggle.” In The Long Struggle of Eritrea for Independence and Constructive Peace, edited by L. Cliffe and B. Davidson, 67–84. Nottingham: Spokesman, 1988.

- Van Alphen, E. Caught by History: Holocaust Effects in Contemporary Art, Literature, and Theory. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

- Van der Laarse, R. “Beyond Auschwitz. Europe’s Terrorscapes in the age of Postmodernity.” In Memory and Postwar Memorials. Confronting the Violence of the Past, edited by M. Silberman and F. Vatan, 71–92. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Vergari, M. “Italian in the Linguistic Landscape of Asmara (Eritrea).” Ethnorêma; Lingue, Popoli e Culture 11 (2015): 95–106. http://www.ethnorema.it/rivista-presentazione-link/numero-11-2015.

- Vormeer, M. “‘English Makes Us Look Good’: English in the Linguistic Landscape in Asmara, Eritrea.” MA thesis, Tilburg University, 2011.

- Wang, X. “Consuming English in Rural China: Lookalike Language and the Semiotics of Aspiration.” In Language and Culture on the Margins: Global/Local Interactions, edited by S. Kroon and J. Swanenberg, 202–229. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Wang, X., and S. Kroon. “The Chronotopes of Authenticity: Designing the Tujia Heritage in China.” AILA Review 30 (2017): 72–95.

- Woldemikael, T. M. “Language, Education, and Public Policy in Eritrea.” African Studies Review 46, no. 1 (2003): 117–136.

- Wright, M. W. “Ideologies and Methodologies in Language and Literacy Instruction in Postcolonial Eritrea.” PhD thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2002.