ABSTRACT

Insights into the role of changing historical-political-cultural contexts and social norms in shaping adolescent girls’ and boys’ futures contributes to an understanding of human development at the intersection of gender and youth in low- and middle-income countries. This study investigates the capabilities and aspirations of adolescent girls and boys and their evolution in Amhara against the background of three successive political regimes that governed Ethiopia over the last 90 years, the Haile-Selassie imperial regime (1930–1974), the socialist military Derg regime (1974–1991), and the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (1991–2019), each with their own institutions, structures and infrastructure, and gender- and age-related relations and norms. The study adopts a capability approach with a gender and generationing development lens as a framework and relies on qualitative data collected through community- and mixed-generation group discussions. The study illustrates that, even if institutional and structural barriers became less stringent over time, cumulative gender- and age-related obstacles – some rooted in beliefs, norms, traditions and relations – hindered the expansion of adolescents’ capability success, consistently more so for girls than boys. (The threat of) gender-based violence pervasively constrains girls’ capabilities success and aspirations in spite of more formal protective institutions.

The current focus on human development in development thinking raises the question ‘whether people have greater freedom today than they did in the past’, and ‘whether people’s capability sets are equal or unequal’.Footnote1 These questions are highly relevant for the case of adolescent girls and boys. Adolescence is a critical stage between childhood and adulthood with its own enabling and constraining institutions. It is foundational in determining one’s life course potential. On the one hand, it is the life phase during which restrictions to one’s capabilities and freedom, such as those related to gender, may become stronger.Footnote2 On the other hand, it is a phase during which adolescents, as constrained agents of development, may question, or potentially change, such restrictions through renegotiating their roles and position vis-à-vis others.Footnote3

This study contributes to the understanding of human development in low- and middle-income country contexts, specifically of the role of changing structure and institutions, as well as social and gender norms, in shaping adolescents’ futures.Footnote4 A first contribution is the analysis of central human capabilities and aspirations of three generations who faced distinct political, institutional, cultural and socio-economic contexts as adolescent girls and boys in Amhara, Ethiopia. A generation is conceptualised as an age-based cohort of people that practiced and shared major life and historical events and have some reflexive and subjective sense of common identity and experiences.Footnote5 The collective and individual capabilities and aspirations of different generations and the inherent power inequalities between groups rest on generational markers.Footnote6 Here, we concentrate on generational markers associated with three successive political regimes in Ethiopia spanning a period of 90 years: the Haile Selassie imperial regime from 1930 until 1974, the socialist military Derg regime from 1974 until 1991, and the regime with the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) as the ruling party since 1991 (until the time of data collection in 2015).Footnote7 Specifically, we explore the ways in which the institutional context – including socio-economic, political, and cultural policy and events – structure and agents, as well prevalent norms and relations related to gender and adolescence, in these three periods have enabled or constrained adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities and aspirations. A second contribution is an analysis of gender differences in adolescents’ capabilities and aspirations and their evolution against the background of the changing contexts.

We acknowledge there are different, sometimes contested, historical narratives in Ethiopia which we cannot do full justice in this study that focuses on regime-related generational markers relevant for adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities. The case of rural communities in Amhara may have implications for the generalizability of this study’s findings.Footnote8 The legacy of Amhara’s central political role, ‘ruling’ over more peripheral areas, particularly before the EPRDF came to power in 1991, its military, cultural and religious dominance, with the continuously influential Ethiopian Orthodox Church, may imply that the regime-related generational markers have a degree of specificity for Amhara.Footnote9 Its demographic and socio-economic characteristics as a large, populous, densely populated, lowly urbanised and relatively poor region in Ethiopia, as well as its persistent history of early (arranged) marriage, may differentiate adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities and aspirations from those in other areas in the country.Footnote10

We continue by discussing the conceptual framework in section two of the paper; methods in section three. The results section shows gender differences in adolescents’ capabilities and their evolution and is followed by a concluding section five.

Capability approach through a gender lens

The capability approach to development hinges on the idea of the expansion of people’s ‘freedom to achieve actual livings’ that they have reason to value.Footnote11 It posits that ‘gender inequality is ultimately one of disparate freedoms’.Footnote12 We adopt a capability approach with a gender lens complemented with elements of the generationing development framework as the conceptual framework for the analysis of differences in capabilities and aspirations by gender and across generations.

The fundamental concept of ‘space of capabilities’ includes the resources, the conversion factors that define the ability to convert resources into capabilities, and the capability to achieve functionings, which are defined as valued beings and doings. Footnote13 In this study, we focus on educational, emotional, and physical and bodily capabilities as well as aspirations. The latter can be seen as an emotional course of actions and future-oriented capabilities linked to emotional capabilities of choosing a life one has reason to value.Footnote14

Agency is the freedom and capacity to choose from and act on alternative functionings.Footnote15 It both ‘generates’ and is defined by capabilities. Individual agency is embedded within, and possibly restricted by, the ‘structure of living together’ which entails diverse (shared) conceptions of and motivations for valuable beings and doings.Footnote16 Such (shared) conceptions and motivations may be partly shaped by asymmetrical power relations and structures. Here we focus on gender and the socially constructed relational concept of adolescence as determinants of asymmetrical power relations and structures.

A capability approach-based theory of societal influences on individuals’ capabilities and achieved functionings points to social relations and structures that derive from the historical-political-institutional context and conversion factors such as social norms.Footnote17

The historical-political-institutional context is characterised by the wider structural setting, existing formal and informal institutions (“rules of the game”) and the power of agents (individuals or groups pursuing particular interest). Feedback loops by which agents of power shape the ‘rules of the game’ that govern the distribution of resources create or consolidate differences in status, power, privilege and access to resources.Footnote18 As such, the historical-political-institutional context can be determinant for expanding or holding back resources and the space of capabilities of specific groups such as, for instance, women and adolescents.

Conversion factors, which are carried out in various institutional domains in society, such as the family, market or community, constrain and enable the way in which the freedom to access resources can be used to act upon and benefit from. Agency and people’s capacity to be active agents pursuing valuable beings and doings therefore are highly dependent on conversion factors.Footnote19 Here we focus on relations and norms associated with gender and adolescence as conversion factors. These influence individuals’ capabilities and achievements in numerous ways, in part, because they allot ‘authority, agency, and decision making power’.Footnote20 They also ‘determine social stratification by reflecting and reproducing relations that empower some groups of people with material resources, authority, and entitlements, while marginalizing and subordinating others by normalizing shame, inequality, indifference, or invisibility’.Footnote21 The fact that norms reflect and reproduce underlying relations of power related to gender and/or adolescence makes them difficult to transform. Those in dominant positions have a critical interest in sustaining asymmetrical power relations.Footnote22 Those in subordinate positions may comply with social norms as a survival strategy, because of a constrained ability to openly pursue one’s interests, or out of fear of social sanctions for deviant behaviour.Footnote23

This does not imply that discriminatory social norms are passively accepted and remain unquestioned. Yet, social transformation, challenging norms and culturally embedded normative understandings of gender, adolescence and power may depend on ‘acting together with others who have reason to value similar things’.Footnote24 Such collective agency relies on building and sharing critical consciousness, for instance, through sharing experiences, solidarity, a common goal or struggle.Footnote25 The generationing development literature emphasises the relational aspect of adolescence in that regard. Common identities and experiences, such as schooling, may facilitate adolescents’ collective agency and engagement with wider development processes, capitalising on horizontal relationships within their cohort. Questioning and renegotiating (vertical) relationships with other age groups, as well as with their envisioned future roles, can be other motors of social change.Footnote26 In the absence of countervailing struggles, however, discriminatory social norms and asymmetrical power relations are more likely to persist rather than weaken over time.Footnote27

Finally, relations and norms associated with gender and adolescence are ‘neither uniform across societies nor historically static’;Footnote28 neither is the institutional and structural setting nor the freedom to access resources. Changes over time can go in all directions, but not necessarily for every generation or both genders in the same way. They can facilitate the weakening of discriminatory norms and asymmetrical power relations helping adolescent girls and/or boys to expand individual and collective agency over time and vis-à-vis other groups in society.Footnote29 Such kinds of ‘liberating’ agency can contribute to adolescent girls’ and/or boys’ capability success and, in a virtuous circle, further expand agency and a life course of well-being and well-doing.Footnote30 In contrast, discriminatory norms, practices and relations can persist or intensify over time by adjusting to changing contexts. For instance, more egalitarian gender norms might be perceived to go against cultural and religious values and provoke antagonistic responses.Footnote31 If such resistance expands, discriminatory norms might retake ground, limit agency and contribute to capability failure, and, in a vicious circle, aggravate constraints to agency and capability success.

Research methods

We adopt a feminist constructivist perspective which calls for qualitative methods relying on deep, interactive, critical engagement with both powerless and powerful society members as a way to understand the multiple realities.Footnote32 We acknowledge that we, as researchers, actively engaged in the research process at different stages and that our choice of the topic and research methodology is not impartial. We recognise that our own experiences and consciousness as women and feminist researchers originating from Ethiopia and Western Europe may have become a part of the research process.Footnote33 Likewise, interviewers were encouraged to be reflexive about their potential influence.

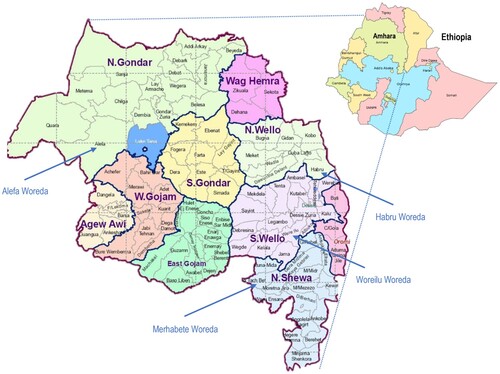

Data was collected from December 2014 through February 2015 in rural communities in Amhara region, specifically in Alefa, Habru, Merhabete, and Woreilu woredas ().Footnote34 The first type of qualitative data was collected through in-depth interviews about the respondents’ lived experiences as an adolescent girl or boy with members of intergenerational trios (IGT), which are all-male or all-female groups including a grandparent, parent and adolescent. Two IGT were conducted in Woreilu, three in Merhabete, and five in Alefa. An analysis of IGT comparing perspectives by grandparents (between 70 and 75 years old), parents (32–47 years old), and adolescents (14–17 years old) gives insights into changes across generations. An analysis comparing perspectives by men and women sheds light on gender differences in adolescents’ capability sets that can be analysed across generations.

Figure 1. Location of study woredas in Amhara Region. Source: Ethiopian Demography and Health, “Amhara” and Jfblanc https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93949036.

The second type of data was collected through historical community timelines (CMT), which are mixed-gender group discussions with six up to 10 community members (aged between 20 and 75 years) who were adolescents during one of the three regimes. CMT enabled exploring general community-level views and experiences of adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities and aspirations and changes over time.Footnote35

Data from IGT and CMT were analysed using NVivo 11. The data were coded by applying labels, enabling the identification of patterns and meanings, after which they were grouped into themes identifying common issues during each regime, including marriage, education, aspirations, mobility and violence.

Interview guidelines for the IGT and CMT facilitated capturing a complete and diverse range of perspectives while maintaining consistency and objectivity (on the part of the interviewer). Visualizing timelines and anchoring to historical political regimes or respondents’ generation helped to overcome some of the challenges related to oral accounts of historical facts and perspectives. In case of long recall, probing facilitated accuracy and synchronisation of the respondents’ time period focus. To avoid nostalgic overly positive (or negative) accounts of one’s own family or childhood interviewers moved the focus towards the community in general.

To address concerns that respondents’ relatively privileged or subordinate positions may have shaped their lived experiences and how they understand social realities, Footnote36 IGT and CMT participants were diversified by social position, locality, religion, education level, and life courses. This sampling of IGT should avoid a picture solely shaped by ‘path dependent’ lived experiences related to the families’ status and power in society. Specific family trajectories may still have some influence. Therefore, where relevant, information about family characteristics is provided.

Procedures for adults relied on informed verbal or written consent. In case of minors, consent by the caregiver(s) and assent by the minor were sought.Footnote37 Data was anonymised and people listening in was avoided. Anonymity towards other IGT and CMT group members and confidentiality could not be ensured. Overdisclosure or potentially distressing topics were carefully managed by interviewers.Footnote38 Power relations along axes of age may have played out during IGT in subtle ways, and along axes of age, gender, and/or socio-economic status during CMT. Interviewers were cognisant of and able to respectfully navigate power hierarchies and local etiquette while actively encouraging all respondents to express their views. If needed, the youngest of an IGT could be interviewed separately.Footnote39

Results

Adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities and aspirations during the Haile Selassie imperial regime

The imperial regime as a generational marker

The imperial regime was characterised by a centralised monarchy under the reign of emperor Haile Selassie. The constitution entitled the emperor to ultimate power over central and local government, the legislature, the judiciary, and the military.Footnote40 While Ethiopia had women political leaders in prior eras, there was no political participation of women in the imperial regime until 1955 when a first female representative sat in parliament. As women slowly entered higher education, women’s participation in (opposition) politics rose, starting from the mid-1960s.Footnote41 Relevant for adolescents’ capabilities is that the Civil and Penal codes under the imperial regime set a minimum age of marriage for both girls and boys and defined betrothal practices.Footnote42

During the imperial period, poverty was pervasive. Access to productive resources was dependent on hierarchical power relationships. These were layered on the basis of socio-economic class with feudal landlords at the top and peasants at the bottom, a caste-like system according to occupation, with artisans lowly ranked, as well as by gender and age (patriarchal). Land was an essential resource and means of production in the agriculture-based economy. Under the feudal system, land ownership was concentrated with landlords.Footnote43 The majority of the population had secondary access to land as a tenant of a landlord.

Education capability

In the recollection of the study respondents who grew up during the imperial period: ‘There was no education […] No woman was educated at that time. Only the sons of balabat [landlords] studied’.Footnote44 According to an elderly man, ‘[w]hat was present at that time was church education’Footnote45 and Koranic education. While religious education was accessible for boys regardless of their families’ status, it was not for girls. Statistics confirm low enrolment rates of 3% for primary and 0.4% for secondary education.Footnote46 The lack of schools and inequitable status-related access to education during the imperial regime constricted adolescents’ education capability. The gendered obstacles left adolescent girls, irrespective of their status, entirely deprived of this capability.

Emotional capability

Marriage was a life goal and an important passage to adulthood. Yet, during the imperial era, ‘children didn’t have the chance to choose their […] future marriage partner’,Footnote47 despite the Civil Code asserting that ‘betrothal shall be of no effect unless both future spouses consent thereto’.Footnote48 A CMT discussant recalls: ‘I had simply accepted the interest of my father for marriage. In the past, nobody was going against the will or interest of his or her father’.Footnote49

Marriage agreements were based on kinship and socio-economic status. ‘If a landlord or well-to-do parents had a baby girl, people would compete to have the girl betrothed to their son before she was six months old’.Footnote50 In the case of well-to-do families, sometimes ‘the requests for a marriage proposition started when the girl was still in the mother's womb’.Footnote51

But, ‘no one wanted to form a marriage alliance with [children of artisans], but they could marry each other’.Footnote52 Since their families could not compete for a marriage alliance with a girl from a well-off family, boys in this class had more voice in choosing their partner and time of marriage. Besides, ‘girls [of artisans or poor farmers] used to be older when getting married […] because no one rushed to marry them’.Footnote53 Yet, ‘they had to wait for a marriage offer from a boy of similar status through the elders [or] they may remain a housemaid for rich households’.Footnote54

Regardless of status, the pressure to marry and marry early was stronger for girls than for boys. An elderly woman explains: ‘During the period of His Majesty, a girl who reached 12 was expected to either marry or die. I myself was married at 12’.Footnote55 Beyond that age, girls were stigmatised as being qomoqär (getting old, unmarriageable), boys were not. Respondents do not recall any awareness of the required consent and minimum legal age of marriageFootnote56 nor any enforcement by punishments foreseen in the Civil and Penal Code.Footnote57

The accounts show that, during the imperial era, both adolescent girls’ and boys’ emotional capability, specifically the choice of marriage partner, was constrained by the norms and expectations of their families. Girls’ emotional capability was additionally restricted by norms prescribing early marriage which were enforced by social stigma. In lower socio-economic classes, boys experienced more freedom in these domains.

Bodily integrity

There was typically a large age gap between spouses. An elderly man recalls: ‘I was married at the age of 20 and my wife was 12 years old’.Footnote58 ‘If the family was in a better economic condition, the marriage could be arranged when girls were five years old and boys were 15 years old’.Footnote59

However, ‘[a]fter a girl was engaged, even at two months of age, she could live with her parents. If the husband was in a hurry [because of his age], the girl could move to her husband’s house at the age of nine [while he may] be 25 years old. […] The father of the bridegroom signed the agreement that the girl would not be forced to sleep with her husband until she was 12. If the husband violates this agreement, the parents were considered murderers’.Footnote60 But, this agreement, known as madego or giyid, ‘was merely a promise, not a written agreement. Nothing happened to the husband and no one would question his parents even if the girl was harmed. It did not go beyond expressing condolence to the girl’.Footnote61 In some cases, ‘parents used to employ a gered [sex-maid] for the boy until the girl was [mature] for sexual relations’.Footnote62 In most cases, a sex-maid was a daughter of poor farmers or artisans.

A woman explained that ‘boys were liked to be tough and jegna [heroes] and girls were liked to be shy’.Footnote63 ‘If a boy is unable to have sex with his wife, some people might gossip and insult him. For this reason, he becomes aggressive […] and satisfies his sexual desire by force. At that time, young girls used to hate themselves […] and suffer from violence and health problems’.Footnote64 Yet, ‘a married girl cannot escape to her mother or withhold sex from her husband as it was considered ill-mannered […] The community used to say to a runaway girl that she is not a good wife and laugh at her [… and they would] also disrespect the mother by saying she didn’t give the necessary guidance about how to become a good wife’.Footnote65

Another constraint to adolescent girls’ bodily integrity, which did not apply to boys, was their restricted freedom to move: ‘It was to protect them from incivility and ill manners. A horse, which is tied for a long time, would cover an entire field running when he is freed once. Similarly, girls might commit a sinful act if they are left free’.Footnote66 Yet,‘[a]bduction and rape were not common because [these] were considered dishonourable to a girl's family. If someone’s daughter was abducted, families felt embarrassed and could seek revenge against the perpetrator’.Footnote67

Despite (ill-enforced) formal policy and some informal protection measures, customs like child marriage, associated large spousal age gaps and societal expectations of boys’ manliness and girls’ modesty, submissiveness, purity and femininity prevalent during the imperial period had detrimental consequences for the bodily integrity of girl children and adolescents, which was less the case for boys.

Aspirations

‘Our only wish was getting married since marriage was our destiny. There was a sense of prestige and good feeling. Getting married was correlated with being wealthy. We [teenagers] were envious of couples passing by, going on family visits and engaging in different local ceremonies’.Footnote68 During the imperial period, adolescent girls and boys were socialised to get married. Their role models were married couples engaged in agriculture. They may not have imagined other life options beyond marriage and making a living from agriculture–individually nor collectively–as their capability to aspire was further constrained by limited opportunities for education and employment outside agriculture.

Adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities and aspirations during the Derg regime

The Derg regime as a generational marker

After overthrowing the imperial regime in 1974, the military DR introduced socialism as an ideological principle for its policies but continued to have a centralised administration and maintained the imperial codes, including the Civil and Penal Codes (but did not enforce them).Footnote69 From 1976 onwards, however, the Derg turned to more autocratic rule.Footnote70

Women played a role in the uprising against the imperial regime and women’s demands were increasingly included in the political agenda. The Derg granted constitutional rights to women and had a gender inclusive discourse. While women helped put reforms for more equal access to land and education on the agenda, women hardly took any important political position. While, initially, there was room for women’s groups and activism, there was cooptation and more oppression after 1976.Footnote71

Smallholder agriculture remained the prime economic activity. But the Derg period was marked by important developments such as the ‘Land to the tiller’ and ‘Basic education for all’ policies.Footnote72 The land reform weakened the hierarchical (feudal) power relationships based on land ownership.Footnote73 Key agents like landlords and authorities of the centralised imperial regime were replaced by authorities of the Derg. Consequently, some institutional and structural constraints were relaxed, such as the power relations and social inequalities related to feudalism and feudal land ownership as well as the lack of primary schools. The caste-like system linked to occupation and patriarchal relationships based on gender and age and related power relations and social norms, however, prevailed.

Education capability

Our respondents remember that during the Derg period: ‘Teachers were assigned to each and every kebele [locality] and basic education was given to everyone’,Footnote74 including in rural areas. ‘We, both children and adults, started to attend classes in temporary shelters constructed around churches as learning centres’.Footnote75 Statistics confirm an increase in the gross enrolment ratio (GER) in primary education from 16% in 1973–41% in 1988.Footnote76

However, ‘people had never understood the importance of education and so nobody studied. Those who were rich were paying bribes and took their children out of school; otherwise, the government was forcing people to enrol in education’.Footnote77 ‘Sometimes, the police used to force us to attend school and send our children to school; or else, we might be prosecuted by the court’.Footnote78 Some ‘parents who had an educated relative had the chance of getting advice […] and sent their children to school. The rest of society did not want to send children to school’.Footnote79 ‘[Parents preferred their boys to] attend church education and their girls to be balemuya set [feminine and good at domestic work]’.Footnote80

‘The right to female education was first enacted during the Derg regime’.Footnote81 However, ‘most people had the wrong attitude about the value of girls’ education […] and didn’t expect something fruitful from [it]. They believed that home is the right place for women and schooling is only the fate for boys, speculating that girls are going to bring Dikala [an out-of- wedlock child] if they [go] to school’.Footnote82 ‘But’, according to a woman, ‘I have never seen a girl who was pregnant while attending school. Some girls successfully completed their education without being exposed to such problems’.Footnote83 Studies and statistics corroborate that girls’ enrolment rates increased but remained lower than boys’ in rural areas in Ethiopia.Footnote84

Emotional capability

Generally, marriage remained an essential passage in adolescents’ lives. ‘[W]hen the land policy changed, the context for marriage also changed. [Nobody] delayed to arrange a marriage for his or her children due to landlessness. […] Everybody had land equally and started to have [expensive] marriage ceremonies’.Footnote85 Child marriage for both girls and boys seemed to have become even more prevalent as a result.

Being qomoqär continued to be a taboo for girls and a disgrace for the family. ‘During our time, people used to prearrange a marriage for their daughters early to avoid the risk that they would be left behind. It was considered prestigious for parents when daughters were chosen and engaged for marriage at an early age. Otherwise, parents used to feel utterly humiliated if their daughter was not considered for marriage in the community’.Footnote86

Some girls, however, were able to defy the norm of being married off at early age. An elderly man witnesses: ‘[M]y daughter was educated. There were frequent marriage requests and we tried to marry her off. But she was extremely resistant to marriage and rather continued her education’.Footnote87

The testimonies suggest little changed regarding the capability of adolescents to choose their spouse and time of marriage during the Derg period. If anything, the alleviated economic constraints of land access seemed to have increased the prevalence of arranged child marriages. This is likely to have exacerbated the constraints to the emotional capability of adolescent girls more than boys’ given gender norms promoting early marriage particularly for girls. For some adolescent girls the expanded opportunities for education, which possibly contributed to their agency in renegotiating roles and expectations in interdependent family relationships, provided an opportunity to escape early marriage and expand their emotional and educational capabilities.Footnote88

Bodily integrity

Adolescent girls’ bodily integrity in marriage remained threatened during the Derg period. ‘It was difficult for young couples to participate in diverse social life in the community. Especially, managing their house and bringing up children was a very difficult task for most girls’.Footnote89 ‘[Young married girls] usually were not able to handle their marriage properly and that eventually could lead to a husband hitting his wife’.Footnote90 ‘Some girls were forced to have sex with their husband at the age of 10 or 12. So they were exposed to fistula and other related diseases’.Footnote91

Adolescent girls’ capability to move freely continued to be restricted. “Girls were insulted when they were found playing outside because that is not a feminine manner”.Footnote92 A woman explains: ‘The community needed girls to be good at domestic activities […] Boys could do anything outside of the home and were strong enough to face challenges. Girls were weak in this regard. They might be exposed to many problems if they stayed outside of a home for some time’.Footnote93

Political instability when conflict erupted between the Derg and its opponents changed boys’ freedom of mobility: ‘[The] Derg used to take our boys to the warfront, recruiting them by force’.Footnote94 The assignment of soldiers to kebeles to control the uprisings formed a danger for girls as well: ‘[T]hey used to rape girls in the woods. The rate of rape was high and there was no legal protection’.Footnote95 ‘Girls were abducted and were forced to marry the one who abducts them. Beyond these, there was no action taken to protect girls’ rights. No one brought the issue to court’.Footnote96 Parents therefore prevented girls from going outside and married them off early as protective measures, constraining adolescent girls’ mobility and emotional capabilities further. Gender differences in capabilities for bodily integrity and freedom to move may have reduced during the Derg period, not because of improvements for girls but because of increased constraints for boys in the context of political instability and insecurity.

Aspirations

Adolescents’ dreams were still dampened during the Derg period. A man recounts: ‘I was attending church education since that was the interest of my family. I later went to a modern school based on my own will and studied up to grade five. However, the community forced me to interrupt because attending school and spending time with girls in class while serving religious activities at the same time was considered a sinful act and prohibited’.Footnote97

‘In the past, people used to trust boys more than girls. Boys could attend church or regular school and be more successful and self-sufficient than girls’.Footnote98 Girls were only expected to be balemuya set to safeguard their marriageability– marriage being the only option for girls and a disgrace for their parents if failing to marry.

Adolescent girls’ and boys’ capabilities and aspirations during the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front regime

The EPRDF regime as a generational marker

After an armed opposition against the Derg regime, in which women played a significant role including as military leaders, the EPRDF ousted the Derg in 1991.Footnote99 Ethiopia passed through important institutional and structural changes and policy reforms. A democratic constitution, giving full recognition to the rights and liberties of individuals, and an ethnic federalist administration were adopted.Footnote100 A national policy on women and women’s affairs offices were set up and women’s civil society organizations emerged. Democracy, however, remained weak and soon democratic reforms shifted to a more restrictive political culture, including regarding women’s collective action. Nevertheless, significant steps have been made in women’s political participation and policy to improve gender equality.Footnote101

The previously state-led economy was liberalised to some extent but sectors remained dominated by state- or party-affiliated oligopolies.Footnote102 There was economic growth but smallholder agriculture remained the dominant economic sector, with some minor reallocation of labour to the service and construction sectors in urban areas.Footnote103 Population increased rapidly. Land became increasingly fragmented in rural areas and land productivity declined. In 1997, a redistribution of farmland took place in favour of landless youth and female-headed households. In 2004, a programme to certify land in the name of both spouses had positive effects on women’s empowerment.Footnote104

Access to basic social services, including education, widened. An invigorated legal and criminal justice system and amendments to the Criminal Code and Family Code have been significant institutional changes for the protection for women and girls against child marriages and violence.Footnote105

Education capability

Since the EPRDF, ‘[primary schools are] available in every kebele. We have got schools near to our village’.Footnote106 Community members also ‘better understand that education has a tremendous relevance for children’s life. That is why they are sending their children to school when they reach school age’.Footnote107 ‘There is no child spending his/her time at home or keeping cattle’.Footnote108 Data confirm near universal access to primary education. The net GER for primary school age children was 97.3% in 2013/14 in Amhara region, with the GPI close to one.Footnote109

The challenge shifted to continuing urban-based secondary education, particularly for girls: ‘I dropped out from eight grade because there is no secondary school near to our locality. My parents could not pay the rent for a house [for us as students] if we would move to town to continue our education’.Footnote110 ‘There are also costs for uniform, school materials, transport and meals […] When parents face financial constraints, they prefer to educate their sons because with educating boys [they] do not have worries […]. In contrast, girls are tied to a wide range of problems like premarital sex, rape or unwanted pregnancy and this strongly holds us back to send girls to secondary school’.Footnote111 ‘Given such problems, parents often force girls to drop out from their education’, according to an adolescent girl.Footnote112

Girls additionally face heavier domestic workloads, impairing their education. ‘My sister has [a greater] household work burden than us [boys]. She is frequently baking Injera [fermented teff pancake], preparing Wot [sauce], washing clothes, cleaning the house compound and other activities. She might do school homework after completing her household duties’.Footnote113 An adolescent girl explains: ‘Boys are also working at home […] but [there is] a [heavier] domestic work burden upon the girls. The attitude of the community towards equal job distribution among boys and girls [has only] partially changed’.Footnote114 Consequently, ‘girls are ineffective in their education […] Girls usually attend school once every two days’.Footnote115

While the motivation for education generally increased, parents express concerns: ‘[C]hildren have passed the whole day in school. But when they [continue] they fail [to pass to advanced levels] and their effort becomes fruitless […] [Our children] neither succeed in their education nor help us harvesting crops. This is frustrating to both the family and the children and discourages parents to send children to school’.Footnote116 ‘Failure to pass and becoming a burden for their family is a common phenomenon […] [Those who] fail regional and national exams and [remain] unemployed are becoming bad role models’.Footnote117 These accounts resonate with Ansell’s observations that schooling and its benefits are at times contested both by adolescents and their parents when their engagement with ‘modernity’ is ambivalent or the economic situation prevents young people with a secondary education to achieve the progress, non-agricultural livelihoods, salaried jobs they – and their parents–aspire.Footnote118

Despite wider access, the costliness of (secondary) education and perceived ineffectiveness as well as gendered norms and (perceived) risks related to the infringement of girls’ bodily integrity form barriers to adolescents’ education capability; persistently more so for girls than boys.

Emotional capability

Marriage remains an important passage to adulthood and life goal, but ‘now, there is no marriage without the girls’ and boys’ consent. Couples decide themselves about everything of their marital fate’.Footnote119 According to an adolescent girl, ‘getting married after a love relationship is regarded as a symbol of modernity. Marrying through a parental arrangement is considered a sign of backwardness’.Footnote120 A mother explains that ‘[n]ow the community developed awareness and leaves their daughters [free] to decide on their marriage. The girls also have better awareness about their right to decide on their marriage […] Girls became resistant against any type of forced marriages [… and] are also supported by the legal regulations on early marriage’.Footnote121 Although the percentage may be higher among women aged 15–29 years, statistics show that still only 15% of ever-married women aged 15–49 years in Amhara region decided upon their marriage themselves.Footnote122

Schoolgirls’ clubs have made a difference, as a member explains: ‘We are discussing about girls’ education and early marriage among other things. We have been told to give advice to our neighbours to educate their daughters. […] When I observe that my neighbours are making preparations for the wedding of their daughters, I will go to the kebele and report their plan’.Footnote123

There are also economic reasons for changed marriage practices: ‘[W]hen the government declared that children should go to school but not marryFootnote124, the community did not accept [this] at first. Then living standards went on dwindling and the community opted to send children to school instead of marrying them off’.Footnote125 ‘If I advise my daughter to interrupt school and marry someone, it creates a problem. I am poor and I am expected to share a plot of land with her. That is why many families are pushing their children to attend school’.Footnote126 A mother states: ‘if they get educated, we hope that they will be employed and they don’t want a share of land from us’.Footnote127

There is, however, pushback from reform opponents. According to Muslim religious leaders: ‘The law which prohibits girls to marry under their 18 is the issue of the government, not religion […] The issue [of early marriage] is not convincing in our [Islam] religion […] If a girl develops sexual interest but remains unmarried, she might follow her interest and commit a sinful act disobeying her parents. If so, she will go against the interest of Allah. The responsibility of such sinful act will lie with the parents for not marrying off their daughter at the right age’.Footnote128 In the view of an Orthodox Christian priest: ‘The gospel states that a girl should marry at her 15 and a boy could marry at his 20. We cannot reject the gospel. The issue of 18 years is the agenda of the government [and possibly] other countries. We have our own rules and strictly abide by that law’.Footnote129 Some community elders are claimed to argue ‘that adolescents are eroding their fathers’ and forefathers’ culture’.Footnote130

A teacher recounts: ‘There are marriages that take place during the night time to hide from government officials or the police. In our school, 15 girls were ready to marry at an earlier age and we managed to cancel those marriages. But teachers are facing a lot of [resistance] from the boys’ side’.Footnote131 Another teacher who chaired a harmful tradition eradication club explains: ‘Within a year, about 25 girls had been prepared to marry at the age of 12 and 13. We were working with the police to stop them. However, we were not as effective as we wanted. The court was also not appropriately penalizing their parents’.Footnote132 According to an adolescent girl, girls are ‘afraid of their parents and feel guilty when they refuse to fulfil the wishes of their parents […] Last year, a student was engaged. The school tried to interfere, but she argued she was 18 and wanted to get married. Actually, she was only 16 and forced to lie by her parents. She did not want to get into conflict with her parents’.Footnote133

Apart from the revitalisation of laws for the protection of women and girls from harmful practices, changed ideas, schoolgirls’ clubs and women development groups and other (non-)governmental interventions have played a role in awareness raising about harmful marriage practices and girls’ empowerment, both at an individual level and by enabling collective agency.Footnote134 This has supported the expansion of emotional capability and freedom to choose when and whom to marry, particularly of adolescent girls. However, (ongoing) relationships of adolescents with their families and community–where some influential members may oppose changes–can inspire the choice to go along with restrictive customs such as an early arranged marriage.Footnote135

Bodily integrity

Adolescent girls’ bodily integrity remains vulnerable: ‘In school there are teachers and at home there are families protecting girls from abusers but on the road there is no one protecting them. Hence, they are facing abduction, rape and consequently dropping out of school’.Footnote136 The violence is happening in spite of ‘legal sanctions to protect girls from rape and abduction’,Footnote137 by which respondents mean that abduction and rape are now considered crimes against personal liberty and moral with long periods of detention as penalties.Footnote138 However, ‘government didn’t assign legal professionals to follow such cases in our locality and those who are available in the social court are part of the society and so they abide by culture rather than the law’.Footnote139 According to some respondents: ‘[I]t is of course better if the families negotiate rather than take the case to a court to avoid conflict between the families, in which case the girls are blamed for causing the conflict’.Footnote140 Consequently, ‘a culture of mediation guards the offenders from accuse and penalty’.Footnote141

Girls’ bodily integrity is under further stress by victim blaming and the importance assigned to the girl’s and her family’s reputation: ‘Girls are abducted in agreement with the boys. […] Even if a girl is abducted or raped without her interest, she will hide herself, as she fears the blame that she did it with her consensus’.Footnote142 ‘[W]e fear our daughters might face rape and abduction. […] That is bad for the girls’ and the family’s name’.Footnote143 ‘Although rape is a crime and culturally immoral, people in the locality gossip about and attack raped girls more than they do the offenders. Most of the time, these girls migrate’.Footnote144

The respondents’ accounts portray a culture of indifference and impunity surrounding (sexual) violence against girls. The consequent fear and risk of gender-based violence impairs adolescent girls’ education and their freedom to move as parents are protective and strictly control their daughters’ mobility. As this does not affect boys, a gender discrepancy in adolescents’ bodily integrity and freedom of mobility persisted during the EPRDF regime.

Aspirations

Currently [at the time of data collection in 2015], ‘children are highly inspired by those successful people who manage to help their family. They dream to reach their level’, according to a mother.Footnote145 An adolescent boy states: ‘I hope that if I work harder in my education, I will be successful in my future life. I hope my parents will support me to successfully complete my education’.Footnote146 The statement by an adolescent girl that ‘as long as we girls can work hard, we can achieve whatever we plan to achieve’ shows that some girls now dare to believe in their self-efficacy.Footnote147 The girl linked this to her participation in a schoolgirls’ club where she developed self-confidence and self-esteem: ‘I want to marry after I successfully accomplish my dreams, [and …] secure my own source of income’.Footnote148

Obstacles remain, however, more so for adolescent girls than for boys: ‘[G]irls are ineffective in [continuing] their education […] They do not even have role models to follow. Hence, when girls reach ten years [of age], they start thinking about marriage […] Because girls know that they will be forced to marry, they do not give [as much] attention to education [as] boys. This is because the society has a different attitude towards male and female children. They don’t want to see their daughters unmarried’.Footnote149 ‘Girls are less likely to get a job after finishing tenth grade. Boys, on the other hand, can wander here and there and get jobs […] [G]irls remain at home waiting for somebody to marry, even after completing their secondary school education’.Footnote150

Adolescent girls face restricted job opportunities: ‘If I fail to pass grade 10, I want to go to a remote area and engage in income generating activities like boys in our community. But being a girl, I couldn't travel to such areas as I fear the situation there’.Footnote151 Another adolescent girl who considered establishing her own tearoom explains: ‘Every man wants to have a sexual relationship with a single woman who owns a bar or a tearoom. […] I got married to feel secure’.Footnote152

Both boys and girls can have bigger dreams than in previous times. They can aspire to pursue secondary education, university, a job or own a business. A girl’s account of finding belief in self-efficacy through school and the schoolgirls’ club illustrates the importance of adolescents relationships’ within their age groups where they can find shared identities and goals, which could spark collective agency for challenging barriers at the level of their families, communities or society.Footnote153 Structural constraints due to limited job opportunities in a still largely agriculture-based economy, however, dampen expectations and aspirations of many.Footnote154 While adolescent girls gained, and (collectively) negotiated, self-confidence, empowerment and larger aspirations, gendered obstacles related to norms and expectations regarding marriage and bodily integrity continue to constrain girls’ aspirations and achievement more than boys’.

Conclusion

This study investigated the extent to which changes over time in the historical-political context, and its institutional and structural setting, as well as changes over time in gender- and age-related relations and norms, have influenced central human capabilities and aspirations of adolescents by gender and across generations in Amhara, Ethiopia. It relied on data collected through community- and mixed-generation group discussions and adopted a capability approach with a gender and generationing development lens as a conceptual framework.

The study illustrates that, during the imperial regime, challenges related to structural constraints, such as pervasive poverty and a (subsistence) agriculture-based economy, infrastructural constraints, such as the limited number and spread of schools, as well as (in)formal institutions and unequal power relations, interfered with the capability success of adolescents. Both adolescent girls’ and boys’ education capabilities and aspirations were constrained by the extractive institution of feudalism, power relations based on land access, occupational class and a patriarchal system, and associated norms. Gendered obstacles, such as norms and expectations of femininity, purity and marriageability as well as intergenerational expectations around marriage constrained particularly adolescent girls’ agency, their emotional capabilities, bodily integrity and aspirations.

The Derg regime came with policy reforms significantly reducing (infra)structural inequalities in access to resources and services. Wider access to schools enabled adolescents’ educational capabilities–even if boys’ education continued to be prioritised as girls’ marriageability remained vital. In contrast, as land access did not hinder (early) marriage anymore, adolescents’ emotional capabilities became more strained; while gendered and (inter)generational obstacles continued to disadvantage adolescent girls. Constraints to bodily integrity rooted in gendered norms and customs persistently affected adolescent girls more than boys. Boys’ freedom to move became more restricted given political instability and insecurity. More universal access to education could have inspired more ambitious and diversified individually and collectively held aspirations and fuelled adolescents’ agency challenging expectations in interdependent relationships with their families and communities or other (gendered or age-related) structures.Footnote155 The limited evidence of such forms of collective agency, however, could relate to a lack of critical mass exposed to education and/or strong, nearly unquestionable, norms and expectations, barriers likely to have been stronger for girls than boys.

In the course of the EPRDF regime, capability success expanded for adolescents in the domains of education, freedom of choice in marriage and aspirations, especially for girls, which reduced gender differences. The forces behind such expansion are a combination of changed formal rules in favour of equal access to resources and services, including education, and protection of women and girls from harmful practices, and more informal institutional changes, including greater awareness and collective action around women’s and girls’ rights, (collective) ideas of modernity and shifts in families’ and communities’ expectations vis-à-vis adolescents, girls in particular. Adolescent girls’ resistance and negotiations for an expansion of their capabilities and freedom were likely supported by such forces. Capability failures in terms of adolescent girls’ bodily integrity, which hamper girls’ educational capabilities and aspirations, however, seem to have persisted. While formal rules protect girls from forced early marriage and gender-based violence, informal norms and practice change at a different pace and, in some cases, change is held back by reform opponents. Hence, collective and girls’ individual agency may not always be a match for strongly held norms and expectations in interdependent relationships with families and communities.

Generally, across generations, adolescents’ aspirations seem persistently influenced by marriage as a key life goal but also by structural constraints related to an agriculture-based economy and poverty as well as by constraining norms and expectations associated with gender and/or adolescence. The fact that adolescent girls are insistently less likely to enjoy the freedom to lead a valuable life than adolescent boys is neither a specific outcome of institutional barriers nor solely a result of structural barriers but rather a result of cumulative gendered obstacles. Multiple obstacles, some of which rooted in beliefs, norms and traditions and justified by cultural and religious values, have persisted across generations, despite being harmful or made unlawful and conflicting with changed structures and institutions. The pervasive influence of (the threat) of gender-based violence on girls’ capabilities success and aspirations stands out.

Some of this study’s insights can be relevant for today’s context of Ethiopia where women’s empowerment and gender transformative change are envisioned and structural transformation may bring new roles for future adult populations.Footnote156 The study illustrates the potential and limits of formal policy and legal frameworks and provides insight into how these could be complemented with programs stimulating change in informal ‘rules of the game’ (norms, beliefs, attitudes and practice) by working with the wider community–influential gatekeepers in particular–and by supporting women’s and girls’ collective agency. Even if not directly acknowledged by the study respondents, women’s increasing voice in politics and policy-making likely played a role in changing (in)formal institutions as well. Finally, while universal access to education emerges as the strongest driver of social transformation across generations, our study illustrates the challenge of aspiration–achievement gaps, with risks of gender discrimination creeping in,Footnote157 which may need to be carefully addressed; especially in the face of the current political and economic insecurity.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding by the UK Department for International Development for the assessment of interventions addressing early marriage and underinvestment in adolescent girls’ education in the Amhara region and financial support by the Institute of Development Policy at the University of Antwerp for the write-up of this article. We thank Sara Geenen, Sarah Vancluysen and anonymous reviewers for useful comments on earlier versions of this article. We express our gratitude to the respondents for their time and commitment to answering our questions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Alkire and Deneulin, “Human Development Capability Approach”, 31.

2 Mensch Bruce, and Greene, The Uncharted Passage.

3 Huijsmans, “Generationing Development”.

4 Nussbaum, Women and Human Development; Robeyns, “Capability Approach Gender Inequality”; Kabeer, “Gender Equality Women's Empowerment”; Alkire and Deneulin, “Human Development”; Marcus and Harper, Gender Justice and Social Norms.

5 Huijsmans, “Generationing Development”.

6 Deneulin, Praxis of Development.

7 There have been major political changes since Dr Abiy became the prime minister in April 2018, as well as significant political tensions, but these were not at work yet at the time of data collection in 2015.

8 In the past Amhara referred to a geographical area. In this study, Amhara refers to a geographical area and Amhara region to the current regional state in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

9 Mahadallah, “Leadership Horn of Africa”; Yohannes, “Horn of Africa (Review)”.

10 About one quarter of Amhara’s population lives below the national poverty line in 2015. CSA, 2015/16 Household Income.

Amhara region has a relatively low median age at first marriage among women of 16.2 years and the highest rate of arranged marriages in the country. CSA and ICF, Ethiopia DHS 2016; Erulkar et al., Ethiopia Young Adult Survey.

11 Sen, Development as Freedom, 73.

12 Sen, Inequality Re-Examined, 125.

13 Alkire and Deneulin, “Human Development”; Robeyns, “Capability Approach: Theoretical”.

14 Nussbaum, Women and Human Development; Hart, “How Do Aspirations Matter?”

15 Alkire and Deneulin, “Human Development”.

16 Deneulin, Praxis of Development; Kabeer, “Gender Equality Women's Empowerment”; Alkire and Deneulin, “Human Development”.

17 Evans, “Collective Capabilities”; Cleaver, “Agency in Collective Action”; Deneulin and McGregor, “Social Conception of Wellbeing”.

18 Cleaver, “Agency in Collective Action”.

19 Ribot and Peluso, “Theory of Access”; Kabeer, “Resources, Agency, Achievements”.

20 Agarwal, “Bargaining and Gender Relations”; Kabeer, “Gender Equality Women's Empowerment”, 23.

21 Sen, Ostlin, and George, Gender Inequity in Health, 28.

22 Scott, Arts of Resistance.

23 Agarwal, “Bargaining and Gender Relations”.

24 Evans, “Collective Capabilities”, 56; Agarwal, “Bargaining and Gender Relations”.

25 Cornwall, “Women’s Empowerment: What Works?”.

26 Ansell, “Commentary ‘Generationing’ Development”.

27 Evans, “Collective Capabilities”.

28 Agarwal, “Bargaining and Gender Relations”, 2.

29 Agarwal, “Bargaining and Gender Relations”; Marcus and Harper, Gender Justice and Social Norms.

30 Sen, Development as Freedom; Marcus and Harper, Gender Justice and Social Norms.

31 Marcus and Harper, Gender Justice and Social Norms; Harper et al., Empowering Adolescent Girls.

32 Stanley and Wise, Feminist Ontology and Epistemology; Mertens, “Transformative Paradigm”.

33 Stanley and Wise, Feminist Ontology and Epistemology.

34 Jones et al., “‘Sticky’ gendered norms”; Jones et al. “Politics advance adolescent girls’ well-being”.

35 IGT and CMT are discussed in Samuels, Jones, and Watson, Qualitative field research gender norms. Interview guidelines for IGT focused on marriage and education are documented in Jones et al., Early marriage and education.

36 Wood, “Feminist Standpoint Theory”.

37 Crivello and Morrow, Ethics Learning from Young Lives.

38 Sim and Waterfield, Focus group methodology.

39 Ibid.

40 Van Der Beken, “Ethiopia”.

41 Meron Zeleke, “Women in Ethiopia”.

42 Penal Code Proclamation No. 158/1957; Civil Code Proclamation No.165/1960.

43 Abbay, “Diversity democracy Ethiopia”.

44 CMT, Habru Woreda (HW), 25 December 2014.

45 IGT-grandfather (GF), Alefa Woreda (AW), 26 February 2015.

46 UNESCO, Development of Education in Africa.

47 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

48 Civil Code Proclamation No.165/1960, 96.

49 CMT, Woreilu Woreda (WW), 20 December 2014.

50 Ibid.

51 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

52 Ibid.

53 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

54 IGT-GM AW 26 February 2015.

55 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

56 Ibid, No.165/1960, 96; and Article 581.

57 Ibid, Article 607; Penal Code Proclamation No. 158/1957, Article 614 Sub-article 3.

58 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

59 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

60 Ibid.

61 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

62 IGT-GM AW 26 February 2015.

63 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

67 Ibid.

68 IGT-GM AW 26 February 2015.

69 Van Der Beken, “Ethiopia”; World Bank, Ethiopia: Legal and Judiciary Sector.

70 Burgess, “Hidden History”; Meron Zeleke, “Women in Ethiopia”.

71 Ibid.

72 Abbay, “Diversity democracy Ethiopia”.

73 While other power relations related to periphery and livelihood may have established. Regassa and Korf, “Post-imperial statecraft”.

74 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

75 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

76 The World Bank DataBank, Education Statistics.

77 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

78 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

79 IGT-mother (M) MW, 18 December 2014.

80 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

81 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

82 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

83 IGT-M AW 25 February 2015.

84 The gender parity index (GPI) for primary and secondary education increased from 0.44 in 1972 to 0.62 in 1988. World Bank, Education Statistics. Ethiopia.

85 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

86 IGT-father (F), AW, 26 February 2015.

87 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

88 Punch, “Youth transitions”.

89 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

90 IGT-F AW 27 February 2015.

91 IGT-F AW 26 February 2015.

92 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

93 IGT-M MW 18 December 2014.

94 IGT-GF AW 26 February 2015.

95 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

96 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

97 IGT-F AW 27 February 2015.

98 IGT-F AW 26 February 2015.

99 Van Der Beken, “Ethiopia”; Meron Zeleke, “Women in Ethiopia”.

100 Ibid.

101 Burgess, “Hidden History”; Meron Zeleke, “Women in Ethiopia”.

102 Hagmann and Abbink, “Revolutionary democratic Ethiopia”.

103 Seid, Tafesse, and Ali., Ethiopia Agrarian Economy.

104 Melesse, Dabissa and Bulte, "Joint Land Certification”

105 World Bank, Ethiopia: Legal and Judiciary Sector.

106 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

107 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

108 IGT-F AW 27 February 2015.

109 MoE. Education Statistics 2006.

110 IGT-daughter (D), WW, 22 December 2014.

111 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

112 IGT-D WW 22 December 2014.

113 IGT-son (S), AW, 26 February 2015.

114 IGT-D WW 21 December 2014.

115 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

116 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

117 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

118 Ansell, “Commentary ‘Generationing’ Development”.

119 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

120 IGT-D AW 25 February 2015.

121 IGT-M WW 22 December 2014.

122 CSA and ICF. Ethiopia DHS 2016.

123 IGT-M MW 18 December 2014.

124 The respondent refers to the minimum age of 18 years for both sexes in the revised Family Code.

125 IGT-F AW 26 February 2015.

126 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

127 IGT-M MW 18 December 2014.

128 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

129 Ibid.

130 CMT AW 25 February 2015.

131 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

132 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

133 IGT-D WW 22 December 2014.

134 Tefera, Pereznieto, and Emirie, Transforming lives girls young women.

135 Ansell, “Commentary ‘Generationing’ Development”; Punch, “Youth transitions”.

136 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

137 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

138 Criminal Code Proclamation No.414/2004, 197 and 620.

139 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

Social courts, staffed by elected or nominated non-professional judges, work alongside the official judicial system and handle minor disputes. World Bank. Ethiopia: Legal and Judiciary Sector.

140 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

141 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

142 CMT WW 20 December 2014.

143 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

144 CMT MW 17 December 2014.

145 IGT-M AW 28 February 2015.

146 IGT-S AW 26 February 2015.

147 IGT-D WW 21 December 2014.

148 Ibid.

149 CMT HW 25 December 2014.

150 IGT-M MW 18 December 2014.

151 IGT-D AW 25 February 2015.

152 IGT-D AW 27 February 2015.

153 Ansell, “Commentary ‘Generationing’ Development”.

154 Ibid.

155 Ansell, “Commentary ‘Generationing’ Development”; Punch, “Youth transitions”.

156 FDRE, Growth and Transformation Plan II.

157 Elias et al., “Gendered aspirations”.

Bibliography

- Abbay, Alemseged. “Diversity and Democracy in Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 3, no. 2 (2009): 175–201.

- Agarwal, Bina. “Bargaining and Gender Relations: Within and Beyond the Household.” Feminist Economics 3, no. 1 (1997): 1–51.

- Alkire, Sabina, and Severine Deneulin. “The Human Development and Capability Approach.” In An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency, edited by Severine Deneulin, and Lila Shahani, 22–48. London: Earthscan, 2009.

- Ansell, Nicola. “Generationing Development: A Commentary.” European Journal of Development Research 26, no. 2 (2014): 283–291. doi:10.1057/ejdr.2013.68.

- Burgess, Gemma. “A Hidden History: Women's Activism in Ethiopia.” Journal of International Women's Studies 14, no. 3 (2013): 96–107.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA). 2015/16 Household Income and Consumption Expenditure Survey. Addis Ababa: CSA, 2018.

- CSA and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2016. Addis Ababa: CSA and ICF, 2017.

- Civil Code of the Empire of Ethiopia Proclamation No.165/1960.

- Cleaver, Frances. “Understanding Agency in Collective Action.” Journal of Human Development 8, no. 2 (2007): 223–244.

- Cornwall, Andrea. “Women’s Empowerment: What Works?” Journal of International Development 28 (2016): 342–359.

- Criminal Code of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No.414/2004.

- Crivello, Gina, and Virginia Morrow. Ethics Learning from Young Lives: 20 Years On. Oxford: Young Lives, 2021.

- Deneulin, Severine, and J. Allister McGregor. “The Capability Approach and the Politics of a Social Conception of Wellbeing.” European Journal of Social Theory 14, no. 4 (2010): 501–519.

- Deneulin, Severine. The Capability Approach and the Praxis of Development. New York: Macmillan, 2006.

- Elias, Marlene, Netsayi Mudege, Diana Lopez, Dina Najjar, Vongai Kandiwa, Joyce Luis, Jummai Yila, et al. “Gendered Aspirations and Occupations among Rural Youth, in Agriculture and Beyond: A Cross-Regional Perspective.” Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security 3, no. 1 (2018): 82–107.

- Erulkar, Annabel, Abebaw Ferede, Worku Ambelu, Woldemariam Girma, Helen Amdemikael, Behailu GebreMedhin, Berhanu Legesse, Ayehualem Tameru, and Messay Teferi. Ethiopia Young Adult Survey: A Study in Seven Regions. Addis Ababa: Population Council, 2010.

- Ethiopian Demography and Health. “Amhara.” Accessed July 22, 2022. http://www.ethiodemographyandhealth.org/Amhara.html.

- Evans, Peter. “Collective Capabilities, Culture, and Amartya Sen’s Development as Freedom.” Studies in Comparative International Development 37, no. 2 (2002): 54–60.

- Family Code of Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No. 213/2000.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE). Growth and Transformation Plan II (GTP II) (2015/16-2019/20). Addis Ababa: National Planning Commission, 2016.

- Hagmann, Tobias, and Jon Abbink. “Twenty Years of Revolutionary Democratic Ethiopia, 1991 to 2011.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5, no. 4 (2011): 579–595.

- Hart, C. S. “How Do Aspirations Matter?” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 17, no. 3 (2016): 324–341.

- Huijsmans, Roy. Generationing Development: A Relational Approach to Children, Youth and Development. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Jones, Nicola, Bekele Tefera, Guday Emirie, and Elizabeth Presler-Marshall. “‘Sticky’ Gendered Norms: Change and Stasis in the Patterning of Child Marriage in Amhara, Ethiopia.” In Empowering Adolescent Girls in Developing Countries, edited by Caroline Harper, Nicola Jones, Anita Ghimire, Rachel Marcus, and Grace Bantebya, 43–61. Basingstoke: Routledge UK, 2018a.

- Jones, Nicola, Bekele Tefera, Janey Stephenson, Taveeshi Gupta, Paola Pereznieto, Guday Emire, Bethelihem Gebre, and Kiya Gezhegne. Early Marriage and Education: The Complex Role of Social Norms in Shaping Ethiopian Adolescent Girls’ Lives. London: ODI, 2014.

- Jones, Nicola, Elizabeth Presler-Marshall, Bekele Tefera, and Bethelihem Gebre. “The Politics of Policy and Programme Implementation to Advance Adolescent Girls’ Well-Being in Ethiopia.” In Empowering Adolescent Girls in Developing Countries, edited by Caroline Harper, Nicola Jones, Anita Ghimire, Rachel Marcus, and Grace Bantebya, 62–80. Basingstoke: Routledge UK, 2018b.

- Kabeer, Naila. “Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal.” Gender and Development 13, no. 1 (2005): 13–24.

- Kabeer, Naila. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change 30 (1999): 435–464.

- Mahadallah, Hassan. “Leadership in the Horn of Africa: The Emic/Etic Perspective.” In The Horn of Africa: Intra-State and Inter-State Conflicts and Security, edited by Redie Bereketeab, 40–69. London: Pluto Press, 2013.

- Marcus, Rachel, and Caroline Harper. Gender Justice and Social Norms-Processes of Change for Adolescent Girls: Towards a Conceptual Framework-2. London: ODI, 2014.

- Melesse, Mequanint, Adane Dabissa, and Erwin Bulte. “Joint Land Certification Programmes and Women’s Empowerment: Evidence from Ethiopia.” The Journal of Development Studies 54, no. 10 (2018): 1756–1774.

- Mensch, Barbaras, Judith Bruce, and Margarete Greene. The Uncharted Passage: Girls’ Adolescence in the Developing World. New York: Population Council, 1998.

- Meron Zeleke, Eresso. “Women in Ethiopia.” In Oxford Encyclopedia of African Women’s History, edited by Dorothy Hodgson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Mertens, D. M. “Transformative Paradigm: Mixed Methods and Social Justice.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1, no. 3 (2007): 212–225.

- Ministry of Education (MoE). Education Statistics Annual Abstract 2006 E.C. (2013/14) Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education, 2015.

- Nussbaum, M. C. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Penal Code of the Empire of Ethiopia Proclamation No. 158/1957.

- Punch, Samantha. “Youth Transitions and Interdependent Adult–Child Relations in Rural Bolivia.” Journal of Rural Studies 18, no. 2 (2002): 123–133.

- Regassa, Asebe, and Benedikt Korf. “Post-imperial Statecraft: High Modernism and the Politics of Land Dispossession in Ethiopia’s Pastoral Frontier.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018): 613–631.

- Ribot, Jesse C., and Nancy Peluso. “A Theory of Access.” Rural Sociology 68, no. 2 (2003): 153–181.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. “Sen’s Capability Approach and Gender Inequality: Selecting Relevant Capabilities.” Feminist Economics 9, no. 2-3 (2003): 61–96.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. “The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey.” Journal of Human Development 6, no. 1 (2005): 93–117.

- Samuels, Fiona, Nicola Jones, and Carol Watson. Doing Qualitative Field Research on Gender Norms with Adolescent Girls and Their Families. London: ODI, 2015.

- Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Seid, Yared, Alemayehu Seyoum Taffesse, and Seid Nuru Ali. Ethiopia—An Agrarian Economy In Transition, 2015/154. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER, 2015.

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Sen, Amartya. Inequality Re-Examined. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

- Sen, Gita, Piroska Ostlin, and Asha George. Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it Exists and How we can Change it. Geneva: Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network, 2007.

- Sim, Julius, and Jackie Waterfield. “Focus Group Methodology: Some Ethical Challenges.” Quality & Quantity 53 (2019): 3003–3022.

- Stanley, Lis, and Wise Sue. Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Tefera, Bekele, Paola Pereznieto, and Guday Emirie. Transforming the Lives of Girls and Young Women. Case Study. Ethiopia, London: ODI, 2013.

- UNESCO. Conference of African States on the Development of Education in Africa. Addis Ababa: Unesco/ ED/181, 1961.

- Van Der Beken, Christophe. “Ethiopia: From a Centralized Monarchy to a Federal Republic.” Afrika Focus 20, no. 1-2 (2007): 13–48.

- Wood, Julia T. “Feminist Standpoint Theory and Muted Group Theory: Commonalities and Divergences.” Journal of Women and Language 28, no. 2 (2005): 61–72.

- World Bank DataBank. “Education Statistics-All indicators” Accessed May 19, 2018. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source = education-statistics-~-all-indicators.

- World Bank. Ethiopia: Legal and Judiciary Sector Assessment. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2004.

- Yohannes, Habtom. “The Horn of Africa: State Formation and Decay.” Review of African Political Economy 45, no. 158 (2018): 687–691.