ABSTRACT

This article explores how local inhabitants living near the Katimok Forest in Baringo County, Kenya, engage with the traces of their past embedded in the landscape, and refigure them into politically powerful ruins. Drawing on ethnographic and archival research, the study examines the traces left behind by former forest dwellers before they were relocated by colonial and post-colonial governments, and analyses the current residents’ interactions with these traces. The article shows that traces are mnemonic and affective devices that remind the local inhabitants of emotional stories of a lost past and foster a sense of belonging. In addition, former forest dwellers and their descendants use these traces as evidence and symbols of their belonging and suffering to demand recognition of their historical loss from current national authorities. By performing the traces as ruins of a lost past, claimants harness their political power. This study highlights the importance of considering forest politics in relation to affective and political engagements with the material landscape.

‘Trouble and the long journey for compensation started when colonial government evicted us from a community land and converted it into forest over six decades ago. Post independent government and its successors only exacerbated our agony’ so reads the testimony of an elder man claiming land compensation in the Katimok Forest, Baringo County, in an article published by the newspaper Reject in December (16-31) 2011. During colonial times, as Katimok became a forest reserve under the control of the district administration, and later of the central government, some of the residents living in the forest were told to relocate. Evictions continued until the late 1980s, several years after Kenya’s independence in 1963. More than three decades later, evictees and their descendants are still living around Katimok, outside the governmental forest boundaries. They are now claiming that the evictions were unjust and that they should be compensated for the loss of their ancestral lands, and the long-lasting suffering it caused them. Pleading the claimant’s cause, the newspaper article suggests that the evictions from the forest are not only about ruined economic livelihoods: they also speak of the separation from ancestral lands, the sense that possibilities for a better future were taken away, and the emotional hardship this entails. It also shows something of the ways in which this history of suffering is being told and used to make a case for compensation and restoration. This article is about the enduring presence of the traces of ruined lives in the forest and their transformations as local inhabitants engage with them in intimate and political ways. It focuses on the affective and mnemonic force of these ruins, but also their political re-appropriation as proofs of belonging and symbols of suffering in the process of claim-making. In short, it shows that forest politics are anchored in affective and political engagements with the material landscape.

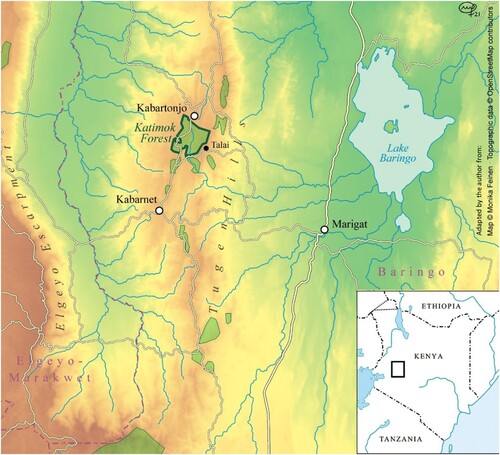

Situated on the Tugen Hills (Baringo County), at an altitude of about 2200 meters, Katimok is a governmental forest of 1956.59 hectares (ha). It is managed by the Kenya Forest Service (KFS), a semi-autonomous agency in charge of the management of forests in the whole country. Katimok is surrounded by human settlements. The majority of people living in the area identify as Tugen (a subgroup of Kalenjin) and most rely on an agro-pastoralist livelihood consisting of both cultivation of shambas (fields) and animal husbandry. This study draws on ten months of ethnographic research in Kenya including interviews, informal discussions with local inhabitants from Katimok and participant observation, as well as archival research ().Footnote1

The first section situates the article and its contribution in the context of literature on claim-making and belonging and the anthropology of traces and ruins. Second, I describe the establishment of state control over the Katimok Forest, during the colonial period and after independence, leading to the dispossession of the local inhabitants and the transformation of the forest landscape. The third section focuses on the material traces of these ruined forest dwelling lives. There, I investigate how, by engaging with these traces in the present, people in Katimok remember and keep the ruins of their pasts alive, bound to the forest as a landscape of belonging. Finally, I discuss the re-appropriation of these traces in claim-making and show that they are transformed into material evidence and symbols of suffering, featured as ruins of a lost past, to support the negotiation of new futures.

Claim-making, belonging and the material lingering of the past

Peter Geschiere has pointed out rising politics of “belonging” in Africa,Footnote2 which, according to Carola Lentz, are embedded in colonial and pre-colonial territorial politics.Footnote3 Also in Kenya, authors have shown that discourses of belonging are used to negotiate and legitimize land and resource claims shaped by historical territorial and forest politics.Footnote4 For Ulrike Kolben Waaranperä, histories of the land and belonging are not only told and used in certain ways to foster land claims, they are also co-constituted in the process, in overlapping emotional and political ways.Footnote5 While these contributions focus on discourses in claim-making, this article aims to investigate the role of the forest landscape, and the material traces of the past in it, in politics of belonging. Authors have emphasized the spatial dimension of belonging that ‘connects matter to place’ through affective connections.Footnote6 Daniel Trudeau shows that landscapes are constructed by territorialized discourses and practices of belonging.Footnote7 This article, by contrast, departs from the engagement of the local inhabitants with the landscape in Katimok, and more precisely with the traces of their past lives there before evictions, to understand how these material traces nurture memories and attachment, but also foster politics of belonging as they are used as proof and political argument in claims on the Katimok Forest.

To do so, this article builds on literature that emphasizes the agency of material things and landscapes,Footnote8 and particularly their affective and political role across temporalities. Ingold theorizes the landscape as ‘an enduring record of – and testimony to – the lives and works of past generations who have dwelt within it, and in so doing, have left there something of themselves’Footnote9: for Ingold the landscape is then essentially made of traces of the past, with which people perceptually engage as they are moving through the environment. Traces have been interpreted and used in anthropological studies historically as material signifiers of culture and as left-overs of a past that may or may not have fully existed, representing the absent.Footnote10 Napolitano understands traces as ‘lingering materialities “looking back at us”, with affective forces of histories’.Footnote11 Also Guillaume Lachenal and Aïssatou Mbodj-Pouye propose to follow the traces (or ruins) of modernity in Africa to understand the political dimension of the affects they convey across time.Footnote12 Moreover, literature on “ruins” has enriched research on the emotional and political power of material vestiges of the past. The concept of “ruins” has been put forward by Ann Stoler to analyze the ‘material and social afterlife of structures, sensibilities and things’,Footnote13 in landscapes shaped by colonial and postcolonial projects and policies. For Ann Stoler, ruins exert a force in the present and the future: ‘the focus then is not on inert remains but on their vital refiguration’.Footnote14 Other authors have looked at the intimate engagement with ruins and argued that affects are produced and transmitted in this relation,Footnote15 so that ruins can be regarded as agents of belonging.Footnote16

I contend that ruins are lingering materialities carrying an affective force, and therefore are a kind of traces of the past, following Napolitano’s definition. By contrast to traces, however, ruins have the specificity to be the product of ruination, that is of destruction, violence and loss – in Stoler’s words, ‘a corrosive process that weighs on the future and shapes the present’Footnote17 – and therefore represent and embody histories of loss and suffering. As a result, ruins carry a particular political force and meaning. This emotional and political force is the focus of this article. I look at the ways in which traces are transformed by the people who interact with them, to fulfill different roles. This study highlights an “ecology of traces” as it follows the threads of entangled human-forest lives through their material manifestation in the landscape.Footnote18 Thinking with Ann Stoler, I investigate how traces become ruins and the political significance of such a ‘vital refiguration’Footnote19 in land claims in Katimok. Doing so, the article highlights the role of the forest landscape and local inhabitants’ attachment to it in political processes of claim-making.

From a dwelling place to a governmental territory: a history of the Katimok Forest

The colonial history of the Katimok Forest starts with the recognition of its value by colonial administrators; a recognition that led in the course of the twentieth century to the progressive establishment of governmental control over the forest and the subsequent dispossession of some of the local inhabitants. Already by the 1910s, in the Protectorate of British East Africa, the administrators of the Baringo district had recognized the forests on the heights of the Tugen Hills as ‘valuable’ for the exploitable cedar, podo and olive trees they contained, and emphasized the need to prevent ‘native’ people from ‘burning and wasting’Footnote20 these resources. By the early 1930s, colonial administrators had come to value three forest areas of the Tugen Hills, including Katimok, as an environmental resource to be protected and utilized. The justification for their designation as forest reserves was threefold. First, the beneficial impact of the forests on local water and soil resources needed to be safeguarded.Footnote21 Second, forest protection was deemed urgent, because local agricultural practices were considered to lead to deforestation and environmental degradationFootnote22 – a common argument in colonial environmental discourses in Kenya and Africa in general.Footnote23 Third, Baringo’s forests were seen as the ‘only source for timber and fuel for local requirements in the district’.Footnote24 By 1933 5587 acres (2261 ha) of land was gazetted as the Katimok Native Reserve Forest.Footnote25 The area remained under the control of the Baringo District Commissioner, while the Forest Department was entitled to inspect the forest management and propose measures for its protection.Footnote26

The gazettement of the Katimok Forest provided for the legal and managerial means to control the forest. It allowed a double movement. On the one hand it set aside the forest to protect it from local disturbances, which became regulated. As such, to the colonial mind, the forest was to be saved from ruination through indigenous agricultural practices. On the other hand, it set aside the forest to make a ‘better’ use of it – that is, to make it more productive, through the establishment of timber plantations and other forms of commercial exploitation. In the colonial gaze, protection and optimization of the forest’s economic potential were two sides of the same coin.

This governmental management ignored local practices of forest management, and aimed to control them through colonial regulations, hence initiating the ruination of local ways of living in the forest. Indeed, the establishment of the Katimok Native Forest Reserve had impacts on the lives of the local inhabitants. Their ways of using the forest became restricted and monitored. Following the gazettement, colonial administrators prevented cultivation to encroach into the forest area,Footnote27 restricted the grazing of sheep and goatsFootnote28 and the barking and felling of trees in the forest.Footnote29 To ensure compliance, Tribal Police patrolled the forest,Footnote30 until in 1938 three dedicated forest guards were employed by the Local Native Council. The Forest Guards prevented the unlawful cutting of trees, and cleared the vegetation on the forest boundaries to make the demarcation visible,Footnote31 so that local residents would have no excuse for trespassing.Footnote32

In 1945, the responsibility for the Tugen Hills forests was transferred from the district level, where the Local Native Council had presided, to the national level, with the Forest Department taking over.Footnote33 In 1949, new gazettements took place in the Tugen Hills,Footnote34 and the Tugen Native Reserve Forest Rules were issued to regulate the local uses of forest reserves. Written permission by a District or Forest officer was now necessary for locals to cut (certain) indigenous trees for their own use and to graze in the forest during the dry season. Building a hut in the forest was only permitted for ‘approved forest cultivators’; and burning in the forest had to be ‘under the direct supervision of a Forest Guard’. However, collection of certain forest products (e.g. firewood, lianas, barks, branches of certain trees, dead trees, fruits), taking animals through the forest and to watering points, grazing sheep, and holding ceremonies were permitted.Footnote35 These rules set a framework that was essentially defined by forest officers. It was the Forest Department, not local people, that now controlled Katimok.

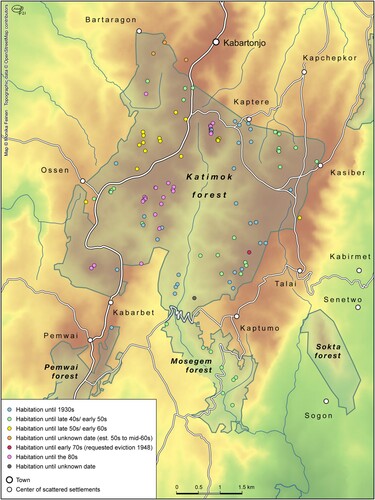

Not only were local ways of life in the forest curtailed by colonial regulations, they were also partly relocated. Several informants indicated that some forest dwellers had to leave the forest in the 1930s after the initial gazettement, and that more relocations followed at the end of the 1940s ().Footnote36 Archival evidence highlights though that permanent and temporary permits were allocated to people living in the forest, from 1949 at the latestFootnote37: permanent permits allowed families to remain settled in the forest, while temporary (but renewable) permits allowed seasonal cultivation in the forest reserve.

In the late 1940s, the exploitation of timber in Katimok by pitsawyersFootnote38 started to develop, growing rapidly in the 1950s.Footnote39 The first three plantations established in Katimok were created in 1950: two plantations of exotic species – cypress (Cupressus lusitanica), and eucalyptus (two Eucalyptus species); and a plantation of the indigenous species Markhamia platycalyx.Footnote40 More plantations of cypress, pines and eucalyptus followed in the 1950s and beyond,Footnote41 transforming the forest landscape in its very composition. By the end of the 1950s, the Forest Department intended to scale up the commercial working of Katimok Forest.Footnote42 But the continued presence of permanent and temporary ‘right-holders’ within Katimok constituted a barrier to this project.Footnote43 To avoid their interference with the forest management and exploitation, the colonial government intended to relocate them on land excised from the forest reserve – this ‘compensating’ them and canceling any future claims.Footnote44 But this proved difficult to implement, as Katimok’s residents contested the rulings and argued against evictions. Negotiations dragged on for years, until the Baringo District administration managed in 1969 to convince local Katimok inhabitants to accept land compensations further away from the area.Footnote45 Although some claimants received land plots after 1969, others did not, and claims over compensations continued.Footnote46

Katimok was definitively emptied from its human inhabitants by 1988, when the Kenya government under the presidency of Daniel arap Moi ordered the expulsion of the last permanent forest dwellers.Footnote47 Moreover, in 1985, the so-called shamba system allowing temporary cultivation inside the forest was also stopped, so that Katimok was left uninhabited and uncultivated.Footnote48 The forest had now become a space dedicated to protection and timber production. This all reflected wider developments in forestry management in Kenya. Cutting indigenous trees in the forests around Kabarnet was forbidden from the mid-1980s,Footnote49 and countrywide in 1986.Footnote50 While the ban prevented indigenous forests from being depleted, exotic plantations were increased to compensate for the non-exploitation of indigenous timber. Also in Katimok, from the establishment of the first hectares of plantations in 1950, the forest increased its production of exotic timber.Footnote51

Thus, governmental forest policies under colonial rule and after independence led to the ruination of the forest as a dwelling place. The forest became an uninhabited bounded territory, rather than a place to live. Local practices in the forest were ignored, regulated and/or relocated by a governmental management focused on the forest as a resource to be protected, improved and exploited in the pursuit of local and national economic development.

However, even as people left the forest, traces of their forest lives were left behind: hearth stones remained in place and the vegetation still bore the traces of former shambas and homesteads. Moreover, the forest in Katimok remains entangled materially with the lives of the people living around its boundaries. Since 1999, a shamba system for people living outside of the forest reserve has been reintroduced,Footnote52 and in 2023, local residents could still be granted a plot to cultivate within Katimok for a few years, before it is replanted with tree seedlings. Since February 2018, a moratorium has been issued by the government forbidding any logging in forest reserves across the country.Footnote53 However, many people around Katimok continue to access the forest to graze their animals and collect firewood, herbal medicine, fodder, fruits, vegetables, and other forest products,Footnote54 some of which are supposed to require a (charged) permit (e.g. for firewood or gazing) delivered by the Kenya Forest Service. Finally, the expulsion of the forest dwellers has generated a politics that still shapes lives in Katimok. Claims from forest evictees and their descendants are still ongoing and under investigation in 2023, as we shall see later in this article.

The forest, a living ruin: affects, memories and belonging

The history of the Katimok Forest continues to weigh on the lives of the local residents, through material traces persisting in the landscape. In this section, I investigate how these traces are engaged with by local inhabitants as the ruins of a lost past. In their intimate engagement with the forest landscape, I show that people remember, account for, and transmit their own past. Ruins act therefore as affective and mnemonic devices (like Wangui Kimari shows, in this special issue) and agents of belonging in the present.

Walking in the forest with local inhabitants, it becomes apparent that areas within the forest bear the names of the families that used to live there. In the Tugen language, the prefix ‘Kap-’ is used to indicate both a place and a lineage.Footnote55 For example, ‘Kapchebyegon’ would be the place of a man called Chebyegon. But, ‘Kapchebyegon’ could also be the denomination of the lineage founded by a man called Chebyegon, encompassing his descendants. The forest is filled with such names, denoting lineages, and their place in the landscape. These places also fit in wider territory divisions, by clan affiliations. Place names show that the forest is divided along clan, subclan and lineage territories, and that within the Katimok Forest, different family lands meet.

The official establishment of the Katimok forest reserve ignored these pre-existing territorial boundaries along lineages. Yet, people living around the Katimok Forest, and whose ancestors used to live inside the forest, still remember these boundaries, acknowledge them, and behave to some extent according to their delimitations.Footnote56 For example, an informant pointed out that people continued to use the locational names of family territories to orientate themselves when in the forest, or in reference to it.Footnote57 All informants also confirmed that beehives cannot be placed in the forest on land belonging to another clan or subclan.Footnote58 Thus, despite the fact that they are no longer inhabited since the evictions, places in the forest associated to clans and lineages continue to be remembered and accounted for. For the local inhabitants, these familiar territories continue to structure the landscape; they are the left-overs of a local territorial organization supplanted – and ruined – by the governmental forest management.

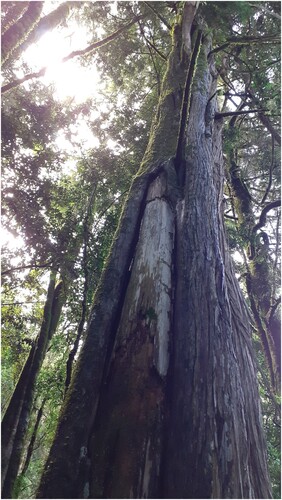

Furthermore, particular places and landmarks in the forest remind local inhabitants of their own history. For example, James,Footnote59 in his 30s, took me around walking in Katimok, following what he repeatedly called the routes that ‘his ancestors’ had been using for many years, and that people are still using. He also directed my attention to cuts on the trees (), explaining that it was cut off by his ancestors living inside the forest, for the protection of their beehives against the rain. Passing by a cliff, he recounted a story that his grandfather told him while herding in the forest: long time ago, when another tribe would come to raid them, the people living here (and their animals) could quickly escape and hide by going down the cliff.Footnote60 Whether such tales are true or not is irrelevant: the point is that the forest gives such stories a material anchorage – and constitutes a physical landscape of memory.

Many forest dwellers or descendants of evictees took me inside the Katimok Forest to the places where their family used to live, showing the locations of former houses and fields and other locations that were important to them. One informant, Peter, brought me (twice) to his former home in the forest, where his family used to stay until the 1980s. He showed me where the houses of his parents and brothers used to be, where they cultivated, and which fruit trees they had planted. He indicated the former location of his grandfather’s hut by pointing to stones he explained were the remnants of a hearth. Along the way, he also pointed out the grave of his parents and a child of his. Peter was born in the late 1930s. As we were walking the first time, he remembered the difficulties that came as colonial rules were imposed on the forest, especially the obligation to keep their animals out of the shamba system areas. After independence, he explained that his family had to cope with more restrictions, like his mother, he recounted, who was arrested for illegal grazing in 1985. Peter also shared the distress it was when they had to leave, and their houses were burned. He explained that his animals died because they had no more food after their land (where they used to graze) was taken away.Footnote61 The second time he took me around, Peter decided to show me a small cave at the foot of the hill where his family used to live. He explained that the cave was used long time ago, before the British came, by his ancestor who hid there for hunting. That is why, he went on, the water stream passing in front of the cave still bore the name of his ancestor. Later, Peter guided me to the point where his family used to fetch water and asked me to take a picture of him sitting by the river, because, he said, this place was important to him. He commented: the water in this stream never dries up, and even the cows from nearby town Kabartonjo come to drink here.Footnote62

Peter’s stories and descriptions are typical of all former Katimok dwellers. Physical elements of the forest landscape are the signifiers of belonging and also, often, like in Peter’s case, of histories of loss and suffering. Their names – like the water stream where Peter’s ancestor used to stay and hunt – still convey these meanings. Walking around in the forest, informants remembered their past and their ancestors’ presence there, but also the loss of these forest dwelling lives.

According to Ingold, perceiving the landscape is about remembering, as remembering means ‘engaging perceptually with an environment that is itself pregnant with the past’.Footnote63 Following Ingold’s “dwelling” perspective, in Katimok, as former forest dwellers and/or their descendants move across the forest, they acknowledge and engage perceptually with the forest as a testimony of the past. Material traces of former forest dwelling lives were perceived and shown to me, the anthropologist, as nostalgic representations of a lost past. Yet, they were not inert objects. They triggered memories and emotions as they reminded local inhabitants of their intimate and collective histories but also of their ruination by governmental interventions. Hence, these traces become ruins in the mediation of forest dwellers who remember their loss as they engage with them: they become material remains of a history of dispossession with a mnemonic and affective power.

Through their affective and mnemonic power, forest ruins contribute to the production of a sense of belonging. Clare Risbeth and Mark Powell have put forward the role of memory in developing attachment to place and a sense of belongingFootnote64; and Alessia de Nardi emphasized that the landscape can support memories and emotions and thereby a sense of belonging.Footnote65 Ruins of past forest lives in Katimok support a sense of belonging in two ways. First, they are the material manifestation of the historical familiar and intimate links that bind the local inhabitants to the forest, and of the ruination of this past. As such, they are the repositories and reminders of individual and collective memories and affects. Secondly, ruins of past forest lives in Katimok provide a material anchorage that fosters the transmission of stories to others, like the anthropologist, or the next generations. Thereby, they enable the perpetuation of a sense of belonging across generations. Consider for instance James, who is too young to remember living in the forest, but is aware of where his ancestors used to walk and collect barks, and marked by the stories his grandfather used to tell him while herding in Katimok. Consider also Peter, who can locate the cave where his forefather used to hide for hunting before colonial time, that is, before he was even born.

As Joost Fontein argues in the Boroma hills of Zimbabwe, ruins are not just ‘locating “belonging” in the landscape’ but have ‘a more “active” and “affective” presence’Footnote66: belonging is produced in people’s engagement with these traces of the past. Indeed, former places of dwelling and cultivation in Katimok, hearth stones, the traces of former shambas, bark wounds, a river, etc. are “affective” in the sense developed by Yael Navaro-Yashin: they ‘discharge affects’, that is emotions, sensual experiences, produced in relation with people’s subjectivities but mediated by their material presence.Footnote67 As Peter finds and looks at the hearth stones of his grandfather’s former home, his interaction with the stones sets his memories in motion, and generates affects (e.g. angriness, melancholia). Thinking with Navaro-Yashin, neither is Peter or other humans in Katimok the only subjects, nor the material environments merely objects. Instead, people and material elements, such as the ruins and their human observers in Katimok, ‘produce and transmit affect relationally’Footnote68: Navaro-Yashin locates the agency in-between, in the relation between people and the material vestiges of the past. Ruins in Katimok are agents of belonging, through the affects they produce as forest dwellers engage with them, but also because they support the transmission of individual and collective histories of past forest lives and their loss. Hence, they contribute to maintain a sense of belonging across generations and make the forest a “landscape of belonging”.

Re-appropriating the ruins of past forest lives: making claims

According to Ann Stoler, ‘ruins draw on residual pasts to make claims on futures’.Footnote69 This section examines the transformation of traces of the past into material proofs and political symbols of ruination used to support revendications. It shows the political resonance of the Katimok histories of dispossessions in the present and in future-making practices, as ruins of past evictions are being strategically re-presented in political claims.

The Katimok Forest residents and/or evictees started organizing themselves in the late 1950s, as the government tried to identify ‘right-holders’ and plan for their relocation. The denomination ‘right-holder’ was probably inspired by the movement of forest residents in the Lembus Forest, situated further south in Baringo, who were officially recognized as rightful forest dwellers in 1923, and struggled to finally be successful in obtaining a relocation on excised forest land in 1960.Footnote70 In echo to this success, in the 1960s, forest dwellers in Katimok tried to be recognized ‘right-holders’ in order to access compensating benefits. Individuals and groups complained to local chiefsFootnote71 and sent letters to the government, usually through the Baringo District Commissioner, but with few answers.Footnote72 From the 1970s, some claimants were allocated plots in Rongai and Mochongoi in Baringo. But this did not suffice to settle the claims. Not only did many claimants remain without compensation, even those who got some land argued that the plots they received were too small in compensation to the land they lost and complained that they were asked to pay for these plots.Footnote73

In 2023, claims are still ongoing. The appointment of commissions to enquire into land issues in Kenya opened up new channels for claimants to push their case forward. Since 2010, the National Land Commission (NLC) has been mandated by the new constitution of Kenya to investigate land claims.Footnote74 Among these, the case of Katimok is considered and the NLC visited the claimants in May 2019. Three ‘right-holders committees’ are active in Katimok and aim to represent the families and descendants of who they recognize as evictees. The first includes 778 claimants from the Eastern and Southern side of the Katimok Forest, in the former Ewolel location – who are claiming Katimok as well as the adjoining Mosegem and Sokta forests.Footnote75 The second has 219 claimants – 17 “original rightholders” and their 202 descendants – from the southern part of the forest (Kipkobit, Goitalam and Kaminden areas).Footnote76 Finally, the ‘Tugen Hills forest evictees committee’ aim to federate the claims concerning evictions from the forests of the whole Tugen Hills. Some of the claimants in Katimok have joined this group. It is worth noting, though, that not all of those who call themselves ‘right-holders’ are necessarily involved in the committees. Most claimants request to be compensated for the loss of their land, preferably by getting a plot of land elsewhere, rather than a monetary compensation, because they consider land as an asset that can be invested in and transmitted to the next generation. Most realize that it is unlikely that they could access what used to be their land inside the gazetted forest reserve.Footnote77 Claims in Katimok are therefore both about the recognition of a political status as victims and access to the economic compensation (in terms of land and money).

My argument is that the material traces of their presence and of the ruination of their lives are put forward as ruins of a lost past and transformed into proofs and symbols to make and support these claims. Whether or not they were (active) members of the committees, all the people I met who were evictees or claimed descent from forest evictees, were eager to show me material proof of their past forest lives. Leading me through the forest to the places where their family used to live, they would look for visible elements of their heritage. Several informants showed me hearth stones (like Peter), proving that a house used to stand there ().Footnote78 Some would also point to the absence of large trees in some areas, indicating a place that used to be cultivated or settled in the past.Footnote79 Their eagerness in showing me the traces of their dwellings partly resulted from their hope that my presence and my work could help their case. Most of them would ask me directly how my research could be useful to their claims or urged me to forward their case “to Nairobi”. My status as a foreign researcher was identified as a potential asset to their revendications. Showing me the traces of their families’ dwellings was a way to convince me of the truth of their eviction allegations and eventually bring me to convey their stories, giving them a recognition and visibility that would be useful in claim-making. At the same time, following these traces became a very fruitful method for my research, unveiling the memories and stories of my informants and revealing their transformation into political tools for claim-making. Traces were turned by informants into evidence of their stories, and by the anthropologist into methodological tools to follow these very stories and their political becoming.

Katimok claimants were also eager to show the places of their evictions to the NLC delegation that visited them in May 2019. For that purpose, meetings with the two local claimant groups took place on eviction grounds. Both committees also took the delegation around to show them where their families used to live.Footnote80 Material traces are not limited to physical features in the forest but also include archival materials. Claimants committees put together files with archival documents to present to the NLC. These documents included minutes of barazas (local meetings) from the end of the colonial period, indicating that the administration intended to identify and relocate ‘right-holders’ at that time, and/or copies of colonial temporary cultivation permits, showing that licensed cultivators were officially recognized. The committees also hold copies of notices for ‘illegal squatters’ to leave the forest, from the late 1980s, as proof of evictions, and records of claims made since the late 1950s, such as letters to various authorities and investigating commissions.Footnote81 These documents establish that the Katimok claims are not new but mark a prolonged history of struggle.

Putting these material traces in the forest and the archive forward as evidence fitted the expectations and requirements of the NLC. Indeed, during its visit, the delegation opened the meetings by explaining that they were there to see the facts ‘on the ground’.Footnote82 They asked the claimants to tell their history and to give them copies of the documents they gathered.Footnote83 To be considered by the NLC, claimants have to apply for their case to be recognized admissible as an ‘historical land injustice’ and complete a form to assess whether their situation fits the criteria covered by the NLC.Footnote84 Such requirements shaped the responses of the claimants. In the meetings with the NLC in May 2019, and in their submissions, they emphasized the injustice of promised compensations that never came and stressed the great loss resulting from ‘forceful’ evictions: their huts were destroyed, their shambas were taken away, their animals could not be kept and had to be sold at cheap prices, their children lost access to prosperity.Footnote85 This emphasis on suffering and injustice appears partly instrumental, fitting the categories investigated by the commission and their expectations of what ‘historical injustice’ should comprise.Footnote86

Not only do material traces in the forest and documents fit the NLC’s requirements, they also make the claims of people in Katimok legible and convincing.Footnote87 As pointed out by an organizing member of one committee, producing a file was part of a strategy to make their case more legible to the NLC:

I saw that the information was scattered, so if they … if anything were asked to produce them [the documents], they [the claimants] were going to get into problems. Because the government wants one solid document. […] So, we called a meeting. Then, we now … we discussed and then we advised the right-holders that: “bring all documents”. […] We want to bring them, all of it. Then put it on the table. Then now, I told them to arrange them according to the years, you know, properly. Then we had to prepare now, doing the list, we had to type properly. […] And then, all those documents are to be photocopied properly, then you arranged, then you now made a book. Something that you can present and it’s one solid document which has got all [his emphasis] the information. […] Now that helped a lot. […] a lot! […] when that book was taken to Nairobi, ah! They said … now … this document is correct. That’s why they were given [the] acknowledgement letter.Footnote88

By contrast to the intimate engagement with a landscape of belonging described in the previous section, in this case, local inhabitants strategically harness the political force of traces of the past in the forest and the archive, as objects representing the ruination of their lives. Used in claims, traces of the past are selected and organized strategically to support a narrative of loss and injustice that serves the claimants’ agenda. They are transformed and fixated into ruins, proofs and symbols of belonging and suffering, to make a political statement in front of the commission; to highlight the claimants’ hardship, and so legitimize their claim for a brighter future.

As claimants revisit their pasts to negotiate new futures, ruins are positioned within, catalyze and serve the ‘politics of the present’.Footnote89 Fontein in the Zimbabwean Boroma hills highlights the agency of ruins that ‘constrain, enable, and structure contests of belonging, entitlement, and authority’.Footnote90 Claims in Katimok are about belonging. Through them, claimants represent themselves as ‘forest dwellers’, victims of dispossession, and frame the forest as their home. Doing so, they perform and politicize their identity in relation to the forest, and re-appropriate their intimate bound of belonging to the forest to pursue political goals. In these politics of belonging, ruins are agents. Not only because they have a mnemonic and affective power, as shown in the previous section, but because their materiality shapes and enhances the claims. First, traces of the past constrain the claims: only the material evidence that is available and visible can be used for claims, hence it needs to be strategically selected and presented. Second, traces presented as ruins are powerful proof because they render ruination material and visible. Engrained in the landscape or in the archive, they hold as guarantee of objectivity and make evictees’ claims tangible and legible to the NLC commission eager to see proof ‘on the ground’.

In the political struggles over the forest of northern New Mexico, Jake Kosek demonstrates that the forest becomes both a symbol of belonging as well as a vehicle for claims. He shows that the senses of belonging that tie Hispanos to the forest define these struggles, and that interests and discourses are rephrased to fit politics of belonging.Footnote91 In Katimok, ruins are not just a symbol and vehicle for claims, they are material proofs, carefully and strategically harnessed by the claimants. They do not only help formulating discourses of belonging that are instrumental for their claims to be accepted, they also give these discourses the visible and legible material anchorage that might convince commissioners. They help establishing narratives of historical dispossession as a truth in front of governmental authorities. Ruins in Katimok thus do not only constitute a landscape of belonging, they also shape and foster politics of belonging, opening possibilities for the future.

In the living ruins of past forest lives: a conclusion

This article described the history of Katimok and its enduring presence through persisting material traces in the landscape. It has shown the different ways in which local inhabitants engage with these traces and transform them. First, places in the forest, former hearth stones and other markers of past forest dwelling lives are affective and mnemonic devices: in their interaction through the forest landscape with these traces of the past, former forest dwellers and their descendants remember their histories. This is particularly emotional because it reminds people of their attachment to locations in the forest, but also of the loss of these dwelling places. Therefore, as human inhabitants remember in perceptual engagement with the landscape, traces become ruins: the material markers of a destroyed past. In this emotional engagement, the landscape supports their sense of belonging.

Second, to make their case in front of the National Land Commission (and the anthropologist) claimants in Katimok use archival traces, hearth stones and other vestiges as proofs and symbols of their loss and suffering. Through claim-making, traces of the past are transformed into the ruins of past forest lives, to prove and legitimize requests for compensations. As ruins, these traces are fixed into a material representation of belonging and historical injustice and suffering that claimants are determined to put forward in the pursuit of their revendications. In Katimok, ruins of the past foster politics of belonging in the present.

The first and the second way of engaging with these traces of the past are connected: in both, the landscape provides a material anchorage that represents and recalls the relation of intertwined belonging and loss between local inhabitants and the forest. In the first one, traces remind people of ruined forest lives. In the second one, however, traces are used and transformed into political tools mobilized to prove and denounce ruination. These different functions of the traces show that memories, affects and political leverage are produced in the different engagements between people and the landscape. It does not point to an agency residing solely in the landscape or solely in the local inhabitants, but rather in their relation (as suggested by Navaro-Yashin) through which the different potentials of traces are being enacted. This article thus shows the affective and political role of the landscape as a material record of the past, in the ways local inhabitants see, represent and claim their relation to the forest. It points to the importance to look at political struggles in the context of the material and affective attachments they are embedded in. As the case of Katimok shows, discourses are not enough to understand how claims are voiced and where they draw their political force.

This research emerged from my own engagement with the landscape and the traces of my informants’ past. Traces were useful methodological tools,Footnote92 as mediators between me and my informants: they provided a material anchorage and point of departure for learning from my informants, and immersing myself in their perceptions of the landscape. My presence and quest for the local history also encouraged the transformation of these traces into ruins: it provided my informants with an audience to show these traces as representations of a lost past. Therefore, chasing traces not only allowed me to access and share my informants’ perspectives on the landscape, but also to notice the ways in which they wanted to represent this material heritage. This second aspect became even more obvious, as I became an observer of their meetings with the National Land Commission and witnessed the ways they put traces forward as proofs and symbols of their historical dispossessions. Thus, this research is a record, another trace, fixating in turn, and rendering visible certain significations of the forest, as mediated by the material – sometimes even living – elements of the landscape, my informants, and myself.

Finally, scrutinizing traces in the forest, including living ones in the form of trees and the vegetation, and the meanings and functions that informants imbue in them, opens a window on the social-ecological history and life of the forest, and on the ways in which people and the forest continue ‘becoming with’Footnote93 each other, growing together, in political and ecological ways.Footnote94 Thus, looking for traces and how they transform, we can investigate more-than-human futures in the making.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of my doctoral work at the University of Cologne. It could not have been done without the assistance of Wesley Kandie and Hosea Kemei. I also thank all my informants from Talai and other areas around the Katimok Forest, as well as the people who welcomed and assisted me in the archives in Oxford, Nairobi, Nakuru, Kabarnet, Eldama Ravine and the forest stations in Narasha and Katimok. I also thank Joachim Knab, Mario Schmidt, Uroš Kovač, Michael Bollig and David Anderson for their constructive and helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The following codes indicate the source of cited archives: BLO refers to the colonial archive of the Bodleian Library in Oxford; KNA to the Kenya National Archives in Nairobi; KNA(Nak) to the Kenya National Archives in Nakuru; KFS to the archives of the Kenya Forest Service located in the Kabarnet forest station (Kabfs) or in the Kabarnet regional office (KAB).

2 Geschiere, The perils of belonging; Geschiere, “Autochthony and Citizenship”.

3 Lentz, “Land and the Politics of Belonging”. See also Kuba and Lentz, Land and the Politics of Belonging.

4 Matter, “Struggles Over Belonging”. Other authors have put forward the importance of discourses on autochthony and indigeneity – analyzed by Geschiere as a form of belonging – in land and resource claims in (forests of) Kenya: Lynch, “Negotiating Ethnicity”; Lynch, “Kenya’s New Indigenes”; Médard, “‘Indigenous’ Land Claims”; and Ruysschaert, “Gouvernance forestière au Kenya”.

5 Waaranperä, “Histories of land”.

6 Mee and Wright, “Guest Editorial,” 772.

7 Trudeau “Politics of Belonging”.

8 Ingold, The Perception of the Environment; Latour, Reassembling the Social; Tsing, The Mushroom.

9 Ingold, The Perception of the Environment, 189.

10 Napolitano, “Anthropology and Traces”.

11 Ibid., 61.

12 Lachenal and Mbodj-Pouye, “Restes du développement”. See also Geissler et al. (eds), Traces of the Future on the traces left by biomedical research in Africa.

13 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 194.

14 Ibid.

15 Navaro-Yashin, “Affective Spaces”.

16 Fontein, “Graves, Ruins and Belonging”.

17 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,”, 194.

18 Ingold, “Bindings Against Boundaries,” 1807.

19 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 194.

20 Kabarnet sub-district annual report 1915–16, p. 11; Kabarnet sub-district annual reports 1914–15, 1916–17, 1917–18, BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/BAR/1.

21 Conservator of Forests to the Colonial Secretary, 24th June 1932, “Forests & Policy”, KNA PC/NKU/2/13/2; also see S.H. Wimbush (Assistant Conservator of Forests), 1941, “Report on Forests in the Kamasia Hills”, “Tugen Forest Reserve” KNA PC/NKU/3/7/1.

22 The Conservator of Forests described to the Colonial Secretary the forests of the Tugen Hills as “the only remnants of a once extensive forest” (24th June 1932, KNA PC/NKU/2/13/2); also see the Kabarnet sub-district report 1916–17: BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/BAR/1.

23 Fiona MacKenzie put forward that colonial land management in the Kikuyu Native Reserves in Kenya was legitimized by environmentalist and ‘betterment’ discourses: Mackenzie, Land, Ecology and Resistance in Kenya; Mackenzie, “Contested Grounds”. Hegemonic discourses that framed African environments as degrading and threatened by local populations legitimized environmental policy (often excluding locals), despite relying on little evidence: see McCann, “The Plow and the Forest”; Fairhead and Leach, “False Forest History”; Fairhead and Leach Misreading the African Landscape; Leach and Mearns, The Lie of the Land.

24 Conservator of Forests to the Colonial Secretary, 24th June 1932, KNA PC/NKU/2/13/2.

25 Forest Department Annual Report (AR) 1933, BLO RHO/753.14 r.26; Conservator of Forests to the District Commissioner (DC) Baringo, 10th December 1934, KNA PC/NKU/3/7/1.

26 Ag. Provincial Commissioner (PC) Rift Valley Province to the Chief Native commissioner 10th September 1932, KNA PC/NKU/2/13/2.

27 Baringo District Annual Report (AR) 1933 BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/BAR/2.

28 Baringo District AR 1935 BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/PC/RVP/2/7/3.

29 Baringo District AR 1937, p. 20, BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/PC/RVP/2/7/3.

30 Baringo District AR 1936 BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/PC/RVP/2/7/3.

31 Baringo District AR 1938 BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/PC/RVP/2/7/3.

32 Assistant Conservator of Forests (Londiani) to Baringo DC, 6th February 1937, KNA PC/KNU/3/7/1.

33 Baringo District AR 1945, BLO Micr.Afr.515/AR/PC/RVP/2/7/3.

34 Proclamation no. 15 under the Forest Ordinance, 29th of March 1949, KNA PC/NKU/3/7/1.

35 “The Tugen (Kamasia) Native Reserve Forest Rules” proclaimed 1949, KNA PC/NKU/3/7/1.

36 The map was created from GPS data collected by the author (2019), based on the indications of local inhabitants. Each point represents the location of a household, a group of households or an approximate area of habitation. This map should not be read as a precise enumeration of households evicted from Katimok. It shows the repartition in time and space of habitations within the forest from my informants’ point of view.

37 Handing-over Report, Kabarnet Division, 1959, BLO Micr.Afr.517/HOR/BAR/9; Permits for temporary cultivation (4 years) in Katimok, dated 3rd June 1949, file by the committee of Southern Katimok (2016 – shown to the author in 2019).

38 Pitsawyers are loggers using pitsaws, a type of handsaws.

39 “Katimok Sawmillers” KFS/Kabfs/2/12.

40 “Compartment Register and Plantation Ledger”, KFS/Kabfs/7/12; KFS, Kabarnet, Tenges, Ol’Arabel forests.

41 KFS/Kabfs/7/12; KFS, Kabarnet, Tenges, Ol’Arabel forests.

42 Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) to the Baringo DC, 23rd February 1957, “Tugen Forest Reserves Rules” KFS/Kabfs/17/1.

43 Baringo DC to the DFO, 8th March 1957, KFS/Kabfs/17/1.

44 DFO to Baringo DC, 23rd June 1958, in KNA(Nak) ZT/3/1; Minutes of the baraza (local meeting) at Sawes, 2nd April 1959, by the DC, “Excisions and addition” KFS/Kabfs/8/1.

45 DFO (Londiani), Annual report – 1969 Londiani Division, 24th March 1970, in “District Forest Officers Annual Reports and Correspondence”, KFS/Kabfs/10/2.

46 The number of people formerly residing inside of the Katimok Forest is difficult to assess. Archival evidence from the early 1940s mentions 13 permanent residents in the forest (estimated date, undated document in “Katimok excisions”, KNA(Nak) ZT/3/1.). In the late 1950s, the lists of ‘right-holders’ drafted by the administration also entailed 13 permanent ones with 12 dependants and 18 cultivators (Minutes of the baraza at Sawes, 12th June 1958, in KNA(Nak) ZT/3/1). By contrast, evictees and their descendants in Katimok indicated much larger numbers of former forest dwellers (). This discrepancy might be due to the vested interests of both colonial reporters and my informants. It might also result from administrative categories failing to account for local perspectives. For example, administrative lists in the late 1950s did not include the number of wives (with their own huts) and all the children of the recognized forest residents. Also, forest dwellers used to be mobile and moved within clan lands according to the availability of pasture and cultivation grounds (Notes – walking around Katimok with community members 9th, 28th and 29th June 2019). In this context, the administrative distinction between permanent residents and temporary cultivators to discriminate between ‘permanent’ and ‘temporary’ rights made little sense. Finally, ‘eviction’ might refer to different understandings. For example, some claimants might call themselves ‘evictees’ because they were forced to move their animals out of the forest, while they were still allowed to cultivate within the forest, and hence were not considered evictees by the administration (Interviews with community members 23rd May, 27th May, 24th June 2019; notes – walking around Katimok with community members 23rd May, 10th, 24th and 27th June 2019).

47 Personal archive of a Katimok claimant.

48 “Non-residential cultivation in Baringo District”, 1999, “Shambas” KFS/Kabfs/14/1.

49 Forester (Kabarnet) to the District Forest Officer (Eldama Ravine), 20th March 1986, “Posts general” KFS/Kabfs/2/2.

50 Standing and Gachanja, The Political Economy.

51 Maps of the Katimok Forest early 1960s, late 1960s and 2010 (KFS/Kabfs and KFS/KAB); “Plantation thinning and clearfelling” KFS/Kabfs/7/13; KFS/Kabfs/7/12; KFS, Kabarnet, Tenges, Ol’Arabel Forests.

52 “Non-Residential Cultivation in Baringo District”, 1999, in KFS/Kabfs/14/1.

53 Interview (unrecorded) with the forester, Kabarnet forest station, 15th October 2019; see for example the newspaper article “KFS Diversifies Revenue after Logging Ban Drained Coffers.” The Star, August 2, 2022. Accessed 12 January 2023. https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2022-08-02-kfs-diversifies-revenue-after-logging-ban-drained-coffers/. In April 2023, the Kenya Forestry Permanent Secretary Kimotho Kimani announced that the ban would be lifted to harvest mature trees from July 2023: “Government to Harvest Mature Trees from July – PS Kimani.” The Star, April 19, 2023. Accessed 16 June 2023. https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/realtime/2023-04-16-government-to-harvest-mature-trees-from-july-says-ps-kimani/.

54 Household survey conducted by the author in 2019 on three villages of the Eastern side of Katimok (over 100 randomly selected households).

55 Also described for the Kalenjin Nandi and the Cherang’any (classified as Nandi dialect): Mietzner, “Place names”.

56 Participatory mapping with ten elders representing different clans and subclans around the Katimok Forest, 2019.

57 Interview with community member, 27 May 2019.

58 Notes – walking around Katimok with community members 21 May, 3 July 2019; Interview with community member, 27 May 2019.

59 All names have been replaced by pseudonyms to protect anonymity.

60 Notes – walking around Katimok with community member, 22 October 2019.

61 Notes – walking around Katimok with community member, 21 May 2019.

62 Notes – walking around Katimok with community member, 8 June 2019.

63 Ingold, The Perception of the Environment, 189.

64 Rishbeth and Powell, “Place Attachment”.

65 De Nardi, “Landscape and Sense of Belonging”.

66 Fontein, “Graves, Ruins and Belonging,” 713.

67 Navaro-Yashin, “Affective Spaces,” 12.

68 Ibid., 14.

69 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 202.

70 Anderson, Eroding the Commons; DFO (Londiani) to the Ag. Conservator of Forests (West, Londiani), 14th August 1962, KFS/Kabfs/8/1.

71 For example: Chief of Kamnarok location to the District Officer (DO) Kabarnet, 27th December 1973, KFS/Kabfs/8/1.

72 File by the committee of Southern Katimok; Claimant to the Baringo DC and DO (Kabartonjo), 28th July 1987, “Shamba issue” KFS/Kabfs/14/2.

73 Forester (Kabarnet) to Chief of the Saimo Location, 14th March 1973, KFS/Kabfs/8/1; Claimant to the Baringo DC, 28th July 1987, KFS/Kabfs/14/2; “Katimok Forest Permanent Rightholders Ossen Location” to the Baringo DC 20th December 1994, “Forest Act, Ordinances, Rules & Laws” KFS/Kabfs/9/1.

74 Republic of Kenya, 2010, The Constitution of the Republic of Kenya, art. 67.

75 File by the committee of Katimok, Sokta, Mosegem (2018 – shown to the author in 2019).

76 File by the committee of Southern Katimok.

77 Informal discussion with a Katimok claimant, 14 May 2019; Interviews with claimants in Katimok (29 April 2019; 26 June 2019; 27 June 2019; 2 July 2019; 6 July 2019).

78 Notes – walking around Katimok with claimants (19 April, 21 May, 23–25 May, 13 June, 20–21 June, 27 June 2019).

79 For example: notes – walking around Katimok with community members, 7 June 2019, 20 June 2019.

80 Notes on the NLC meetings with Katimok claimants (Katimok, Sokta, Mosegem and Southern Katimok committees), 14 May 2019.

81 File by the three Katimok committees.

82 Notes on the NLC meeting with Katimok claimants (Katimok, Sokta, Mosegem committee), 14 May 2019.

83 Notes on the NLC meeting with Katimok claimants (Southern Katimok committee), 14 May 2019.

84 NLC, The National Land Commission.

85 Files by the three Katimok committees; Notes on the NLC meeting with Katimok claimants (Southern Katimok and Katimok, Sokta, Mosegem committee), 14 May 2019.

86 On the influence of classifications on human lives see: Bowker and Star, Sorting Things Out.

87 Li, “Locating Indigenous Environmental Knowledge”. Li shows that being able to present one’s claim in a way that is legible by outsiders is one of the conditions for claims on indigenous knowledge to succeed.

88 Interview with a member of a Katimok claimants committee, 26 June 2019.

89 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 196.

90 Fontein, “Graves, Ruins and Belonging,” 715.

91 Kosek, Understories.

92 Napolitano, “Anthropology and Traces”: Napolitano argues that following traces is a useful methodology for the anthropologist to untie the ‘knot of condensed stories’ (61) that constitute a trace, and to analyze the forms that histories are taking as they condense and continue to matter in the present. Lachenal and Mbodj-Pouye, “Restes du développement” also emphasize the following of traces as a heuristic anthropological method.

93 Haraway, When Species Meet.

94 Mathews, “Landscapes and Throughscapes”.

Bibliography

- Anderson, David. Eroding the Commons: The Politics of Ecology in Baringo, Kenya, 1890s–1963. Oxford: James Currey, 2002.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan L. Star. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

- De Nardi, Alessia. “Landscape and Sense of Belonging to Place: The Relationship with Everyday Places in the Experience of Some Migrants Living in Montebelluna (Northeastern Italy).” Journal of Research and Didactics in Geography 1, no. 6 (2017): 61–72.

- Fairhead, James, and Melissa Leach. “False Forest History, Complicit Social Analysis: Rethinking Some West African Environmental Narratives.” World Development 23, no. 6 (1995): 1023–1035.

- Fairhead, James, and Melissa Leach. Misreading the African Landscape: Society and Ecology in a Forest-Savanna Mosaic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Fontein, Joost. “Graves, Ruins, and Belonging: Towards an Anthropology of Proximity.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17, no. 4 (2011): 706–727.

- Geissler, Paul Wenzel, Guillaume Lachenal, John Manton, and Noémi Tousignant, eds. Traces of the Future: An Archaeology of Medical Science in Twenty-First-Century Africa. Bristol: Intellect, 2016.

- Geschiere, Peter. “Autochthony and Citizenship.” Quest: An African Journal of Philosophy 18 (2005): 9–21.

- Geschiere, Peter. The Perils of Belonging: Autochthony, Citizenship, and Exclusion in Africa and Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Haraway, Donna J. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

- Ingold, Tim. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Ingold, Tim. “Bindings Against Boundaries: Entanglements of Life in an Open World.” Environment and planning A 40, no. 8 (2008): 1796–1810.

- Kenya Forest Service (KFS). Kabarnet, Tenges, Ol’Arabel Forests Plantation Management Plan: 2015–2025, 2015.

- Kosek, Jake. Understories: The Political Life of Forests in Northern New Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Kuba, Richard, and Carola Lentz, eds. Land and the Politics of Belonging in West Africa. Leiden: Brill, 2006.

- Lachenal, Guillaume, and Aïssatou Mbodj-Pouye. “Introduction au thème. Restes du Développement et traces de la modernité en Afrique.” Politique africaine 135, no. 135 (2014): 5–21.

- Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Leach, Melissa, and Robin Mearns, eds. The Lie of the Land: Challenging Received Wisdom on the African Environment. Oxford: James Currey, 1998.

- Lentz, Carola. “Land and the Politics of Belonging in Africa.” In African Alternatives, edited by Patrick Chabal, Ulf Engel, and Leo de Haan, 37–58. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- Li, Tania. “Locating Indigenous Environmental Knowledge in Indonesia.” In Indigenous Environmental Knowledge and Its Transformations: Critical Anthropological Perspectives, edited by Roy Ellen, Peter Parks, and Alan Bicker, 121–150. Amsterdam: Harwood, 2000.

- Lynch, Gabrielle. “Negotiating Ethnicity: Identity Politics in Contemporary Kenya.” Review of African Political Economy 33, no. 107 (2006): 49–65.

- Lynch, Gabrielle. “Kenya’s New Indigenes: Negotiating Local Identities in a Global Context”. Nations and Nationalism 17, no. 1 (2011): 148–167.

- Mackenzie, A., and D. Fiona. Land, Ecology and Resistance in Kenya, 1880–1952. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998.

- Mackenzie, A., and D. Fiona. “Contested Ground: Colonial Narratives and the Kenyan Environment, 1920–1945.” Journal of Southern African Studies 26, no. 4 (2000): 697–718.

- Mathews, Andrew S. “Landscapes and Throughscapes in Italian Forest Worlds: Thinking Dramatically about the Anthropocene.” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 3 (2018): 386–414.

- Matter, Scott Evan. “Struggles Over Belonging: Insecurity, Inequality, and the Cultural Politics of Property at Enoosupukia, Kenya.” PhD diss., McGill University, 2010.

- McCann, James C. “The Plow and the Forest: Narratives of Deforestation in Ethiopia, 1840–1992.” Environmental History 2, no. 2 (1997): 138–159.

- Médard, Claire. “‘Indigenous’ Land Claims in Kenya: A Case Study of Chebyuk, Mount Elgon District.” In The Struggle Over Land in Africa: Conflicts, Politics & Change, edited by Ward Anseeuw and Chris Alden, 19–36. Pretoria: HSRC Press, 2010.

- Mee, Kathleen, and Sarah Wright. “Guest Editorial. Geographies of Belonging.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41 (2009): 772–779.

- Mietzner, Angelika. “Place Names and Place Naming Strategies in the Kalenjin (S. Nilotic) Cultural Iandscape, with Special Focus on the Cherang’any.” Studies in Nilotic Linguistics: Information Structure and Nilotic Languages 10 (2015): 209–223.

- Napolitano, Valentina. “Anthropology and Traces.” Anthropological Theory 15, no. 1 (2015): 47–67.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15, no. 1 (2009): 1–18.

- National Land Commission, Kenya (NLC). The National Land Commission Investigation of Historical Land Injustices Claims Rules, 2016.

- Rishbeth, Clare, and Mark Powell. “Place Attachment and Memory: Landscapes of Belonging as Experienced Post-Migration.” Landscape Research 38, no. 2 (2013): 160–178.

- Ruysschaert, Denis. “Gouvernance forestière au Kenya: le cas de la forêt du Maasai Mau.” Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est 34 (2007): 1–55.

- Standing, André, and Michael Gachanja. The Political Economy of REDD+ in Kenya: Identifying and Responding to Corruption Challenges. U4 Issue 2014, no. 3 (2014).

- Stoler, Ann L. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 2 (2008): 191–219.

- Trudeau, Daniel. “Politics of Belonging in the Construction of Landscapes: Place-Making, Boundary-Drawing and Exclusion.” Cultural Geographies 13, no. 3 (2006): 421–443.

- Tsing, Anna L. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Waaranperä, Ulrika Kolben. “Histories of Land: Politicization, Property and Belonging in Molo, Kenya.” PhD diss., Malmö University and Lund University, 2018.