ABSTRACT

What explains youth political mobilization in Uganda – or lack thereof? This article challenges the simple dichotomy of youth as either a dangerous or disengaged political constituency. Instead, we analyze the conditions that determine whether youth can coalesce as a politically salient category. For many, the outcome of the 2021 Ugandan elections defied expectations. A large and underemployed youth population combined with the emergence of self-proclaimed ‘youth candidate’ Bobi Wine, led both international and domestic analysts to predict a strong youth challenge to National Resistance Movement (NRM) dominance. However, while Bobi Wine captured the opposition vote, he was unable to create a new youth constituency that could overcome existing political and regional cleavages. This article draws on interviews and fieldwork on youth political mobilization during the 2021 elections to identify and analyze a range of historically rooted methods that the NRM effectively deploys to mobilize and fragment youth. The findings confirm the need to look beyond rallies and rhetoric to analyze whether the conditions are right to allow youth to emerge as a politically salient category.

In January 2021, Yoweri Museveni was re-elected president of Uganda, securing his position as the sixth longest ever serving non-royal head of state. According to scholars and journalists, his win was not inevitable. Rather, Museveni had faced ‘a strong challenge’: the ‘meteoric rise’ of then 38-year-old Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, popularly known as Bobi Wine, leader of the National Unity Platform (NUP).Footnote1 During the election campaign, Bobi Wine – a popstar-turned-legislator – had been internationally-lauded as the electable face of Uganda’s sizable and struggling youth demographic. Over three-quarters of Uganda’s population is under 30 years old, and up to 70% face unemployment.Footnote2 The regime, too, seemed to see Bobi Wine and the NUP as a threat. In addition to legal manoeuvres, such as blocking Bobi Wine’s initial attempt to register a new political party, the regime unleashed significant violence against Bobi Wine and his supporters. The 2021 elections were the deadliest in Uganda since 1980.Footnote3 Other government measures frustrated the opposition: for instance, the regime stopped registering voters in 2019, disenfranchising up to one million Ugandans who turned 18 in the intervening period.Footnote4 The regime also used COVID-19 containment measures as a pretext to limit campaigning by the political opposition.Footnote5 The final vote tally delivered Museveni 58% of the vote. Bobi Wine took 35%, with especially strong showings in Kampala and in his home region of Buganda.Footnote6 Despite election irregularities and legal challenges brought by the political opposition, Museveni was inaugurated on 12 May 2021.

Without minimizing the significance of regime interference and violent repression, we propose that analysts overestimated the likelihood that the youth vote would bring sweeping political change. We suggest this is because they overlooked the multiple, complex, and embedded strategies and tactics the NRM has used over the years to manage ‘youth’ as a political threat, and to prevent youth from emerging as a political salient category. For example, the regime has disenfranchised youth in the context of youth quota systems; it has offered diverse economic incentives in the form of loan schemes, grants, and short-term employment in the broader context of a robust patronage system; and it has shaped political narratives, including by controlling media access, against the backdrop of entrenched social values that see youth as beholden to their elders and the state. Though youth navigate these realities to carve out benefits for themselves, they do so within the confines of the very structures which obstruct their collective political mobilization. This layered and multifacted approach to capturing ‘youth’ – both as an analytical category and as a constituency that can be mobilized and co-opted – has allowed the incumbent NRM regime to maintain power, even while the youth population continues to grow. These insights emphasize the need to look beyond rallies and rhetoric to understand whether conditions are right to allow youth to emerge as a politically salient category.

Scholarship across Africa often defines ‘youth’ as a socially constructed category characterized by liminality and transition: those who are no longer considered children, but have not yet realized ‘social markers’ that signify adulthood, such as financial independence, marriage, and children.Footnote7 The Ugandan government, in contrast, defines youth as people between 18 and 30 years old.Footnote8 In this article, we study how the NRM – like the regimes that came before it – has produced an all-encompassing, homogenizing definition of ‘youth’ that it uses to support its political agenda. We interrogate this political construction of ‘youth’ by the NRM regime, and we identify how it has been reproduced in NRM policies. Further, we show how NRM strategies to control the youth vote cannot be understood apart from the agency and choices made by young people as they navigate daily realities in a context of limited economic opportunity and profound economic precarity.

We study Uganda as a case that defies expectations. Uganda has in spades the factors assumed to mobilize youth: a large and dissatisfied youth population facing an ever-worsening economic and political outlook, combined with the emergence of a popular and charismatic youth candidate leading a political party that claims to speak for them. Though Bobi Wine did impressively well for a first-time political candidate, he was unable to mobilize youth across the country in the anticipated youth wave. Instead, electoral analyses suggest that voters fell into similar camps as in previous elections, with Bobi Wine becoming the de facto opposition candidate, while Museveni more or less maintained his share of incumbent support.Footnote9 Because it does not conform to widely shared expectations about the success of youth political mobilization, Uganda is therefore a helpful case to re-examine existing explanations for youth political mobilization.Footnote10

The article draws on our collective research on Uganda, which includes foci on politics, security, and justice. We supplement these insights with 16 semi-structured interviews with men and women of different ages and different political affiliations, conducted in Kampala and Gulu during the run-up to and immediate aftermath of the 2021 election, and eight interviews with representatives from NRM youth vote mobilization initiatives. We purposively selected respondents who would have articulate views on politics, and some of whom were engaged in local-level political organizing, but who were not political elites. Although some of our respondents were older than 30, all self-identified as ‘youth’, which is a social category, just as much as an age category amongst Ugandans. As with the majority of Ugandans of working age, all of our respondents worked in insecure and low-income jobs in the informal sector.Footnote11 As such, they all navigated daily realities of ‘precarious’, ‘underpaid’ and sometimes ‘exploitative’ labour in order to make ends meet.Footnote12 Field research took place mainly in Gulu, northern Uganda, a region emerging from the decades-long conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Government of Uganda (1988–2006).Footnote13 Though support for the NRM has faltered in some parts of the country, the regime has recently made political gains in the north. Taking these regional dynamics into account, our fieldsite helps move beyond the urban youth of Kampala, offering insights into how government tactics interface with structural conditions to shape (and limit) prospects for national-level youth mobilization.

After contextualizing our contribution within scholarship on youth political mobilization, we discuss the history of youth politics in Uganda, and then turn to an analysis of youth political engagement in the 2021 elections including strategic and tactical approaches that the NRM regime has used to control and co-opt youth.

Dangerous and disengaged? Questioning the youth narrative

Across Africa, youth are narrated both as holding promise for political liberation, but also as representing the threat of social fragmentation and disorder. From the Arab Spring to the Y’en Marre hip-hop activists in Senegal, African youth have played a central role in political transitions that challenge repressive or authoritarian rule.Footnote14 At the same time, ‘youth’ are sometimes mobilized to represent ‘pathologies’ and ‘monstrosities’: images of child soldiers in northern Uganda and Liberia, for example, epitomize a perverse form of coercive and violent political mobilization.

Whether engaged in non-violent political mobilization or armed insurgencies, youth are understood to share a particular social condition shaped by the common experience of under and unemployment, leaving them trapped in a state of profound precarity. Alcinda Honwana termed this ‘waithood’, in which youth eke out a living but struggle to gain the financial stability necessary to transition to adulthood.Footnote15 For national governments across Africa, youth precarity combined with their growing numbers is regarded as a significant political and security concern. The concept of the ‘youth bulge’ for example, refers to ‘redundant’ and ‘restive’ (male) populations,Footnote16 susceptible to political mobilization, as well as radicalization and political violence.Footnote17 Youth are also often seen as tech-savvy, with access to new and unmonitored pathways to political and social organization. In this sense, male youth are often framed as a uniquely dangerous population that is large, volatile, and seeking to assert claims and disrupt the status quo.Footnote18

While we acknowledge that demographics shape politics, we caution against seeing a large young population as an inevitable source of political volatility. As Sukarieh and Tannock point out, ‘most African nations with youth bulge populations have not experienced recent civil conflicts, and in those that have had conflicts, most male youth never got involved with the violence’.Footnote19 Meanwhile, scholarship on non-violent youth political engagement in Africa largely focuses on disengagement and apathy,Footnote20 showing that despite their increasing participation in political protests, youth cohorts vote at lower rates than older cohorts.Footnote21 This political disengagement has been attributed to ‘recycled political landscape[s]’,Footnote22 in which incumbents rehash narratives of liberation struggles, while opposition parties emphasize challenging incumbents more than developing youth-centred policy agendas.Footnote23

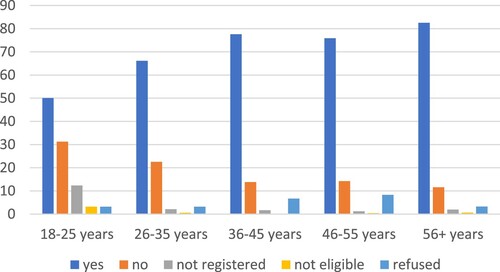

The pattern of low youth turnout holds in Uganda, where 67% of registered voters are estimated to be between 18 and 35 years of age, but vote at comparatively low rates (). To explain youth’s low voting rates in the 2016 elections, MIT researchers conducted qualitative interviews with youth in urban and peri-urban Kampala, Gulu, Mbarara, and Mbale.Footnote24 They found that youth believe they are poorly represented in government, that their vote will have little impact on national-level politics, and that the perceived costs associated with political participation, including intimidation, violent repression, and even detention are too high. To make matters worse, in 2021, the Ugandan Electoral Commission’s closed voter registration a year before the election, potentially disenfranchising an estimated 1 million young voters.Footnote25 While the Commission argued it lacked the technical capacity to register more voters ahead of the election, many saw it as a move against the opposition.Footnote26 In depicting youth as apathetic, short-sighted, disengaged, and disenfranchised, these analyses still imply a latent youth constituency that could be quickly mobilized under the right political conditions.

Figure 1. Voting by age cohort; Source: BIEA/IPSOS (2021) Uganda post-election survey, March/April 2021. Survey available on request from the BIEA.

However, what has been neglected in analyses of the 2021 elections in Uganda is quite a different proposition: the potential for youth to be ‘harnessed’ for ‘state projects’ including electioneering and regime consolidation.Footnote27 Observers placed so much focus on Bobi Wine’s potentially transformative appeal to youth that they overlooked long-term regime strategies to capture and co-opt youth politics and political engagement. In this article, we situate this within broader, historically embedded NRM strategies and tactics to consolidate power and subvert opposition attempts to mobilize support. The result shows why – even in the case of Uganda with many signs pointing to the contrary – ‘youth’ may be unable to organize as an autonomous political constituency. In doing so, we offer a modest corrective to analyses that, we argue, overplayed Bobi Wine’s potential to mobilize the youth vote across Uganda.

Youth politics in Uganda (1919 to today)

Throughout Uganda’s modern history, its successive regimes have largely treated youth as the ‘infantry of adult statecraft’,Footnote28 developing state structures that simultaneously rely on and constrain youth in this way. The possibility of a national youth constituency in Uganda emerged as early as 1919 with the colonial adoption of the Native Council Ordinance. This colonial policy created a population of educated and nationally-employed (male) civil servants, who began to make demands of the colonial administration, including for better pay and improved working conditions.Footnote29 Young people’s associations sprang up across the country. To prevent regionally integrated political dissent, the colonial regime sought to institutionalize links between young men and their home areas, notably by enhancing the authority of elders. As Elizabeth Laruni argues, ‘[T]his set the stage for a generational conflict where elders, feeling threatened by the skills of this newly educated and well-travelled demographic, retaliated by emphasizing the importance of gerontocratic authority and tradition’.Footnote30 The British co-opted youth activists by nominating youth group members to the Native Councils and funding cultural and sports associations to ‘satisfy’ short-term political aspirations.Footnote31 This emerging constituency thus remained regionally fragmented, particularly as political elites instrumentalized ethnic identity.Footnote32

Several decades later, as Uganda’s leading political parties jockeyed for control of the Legislative Council in anticipation of independence, youth were again identified as a constituency of interest. Leading the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC), Milton Obote recruited several young Ugandan leftists to his party, and appointed a youth representative to sit on its Central Executive Committee. In the elections of 1961 and 1962, ‘radical’ young politicians used language of self-determination and anti-colonialism to attract youth across the country to the UPC.

However, the alliance between the UPC and youth soon fractured.Footnote33 The 1960s saw ongoing struggles within the youth wing, and between the youth wing and the UPC, sometimes culminating in violence. The Youth League’s anti-colonial stance conflicted with Obote’s and the UPC’s more centrist leanings. As Taylor writes:

… from 1962 to 1964, elite nationalists, royalists and diplomats all expressed alarm that the UPC Youth Wing was undermining Uganda’s fragile postcolonial political order. ‘We consider the Constitution which is the supreme law of the land is being trampled underfoot in the eyes of the Government by the youths’, warned the MP Stanislaus Okurut.Footnote34

Subsequently, UPC youth moved toward the creation of a separate organization, but were divided on regional and class lines.Footnote35 When UPC leadership became aware of youth efforts to launch a new political party, they abolished the party’s youth league and established organizations under control of the party’s regional executives.Footnote36 These new regional organizations included the National Union of Youth Organisations (NUYO), for agricultural development initiatives for out-of-school youth; and the National Union of Students of Uganda (NUSU), for youth in secondary and tertiary school.Footnote37 As Mujaju explains:

NUYO was supposed to incorporate all existing youth organisations and had such objectives as to create nationalism and patriotism and engage youth in rural development efforts [thereby forcing them to leave urban areas where they were politically active]. But the initial emphasis was placed on total discipline … in order to facilitate the depoliticisation of youth as well as to exercise strict control of their activities.Footnote38

Under Amin (1971–1979), NUSU was banned, and tensions between the regime and students grew.Footnote41 While Obote had used a network of students to monitor political views in the university, Amin took a more conspicuous approach.Footnote42 The disappearances and arrests of some students and, in 1972, the University’s Vice-Chancellor, highlighted the stakes of disobedience.Footnote43 NUYO, meanwhile, was ‘severely repressed’Footnote44, and then replaced with the Ugandan Youth Development Organization (UYDO) in 1976. UYDO ‘aimed to transform delinquent youths into hardworking, vigorous patriots. The organization’s architects argued that, in “our African Social Structure,” children were “owned by the whole community”’.Footnote45

In 1979, Obote – backed by Tanzanian forces – ousted Amin. One year later, in elections marked by political violence and vote rigging, Obote was re-elected. Unable to secure loyalty from the political elite that had been his mainstay after independence, Obote re-engaged Uganda’s youth – a population not so disillusioned with his political rhetoric of ‘progress and development’.Footnote46 Ugandans under 30-years-old already accounted for an estimated 70% of the population, and unemployment rates were high.Footnote47 To maintain power in the wake of growing opposition, including a rebel insurgency led by a young Yoweri Museveni, Obote’s UPC needed to accommodate this large demographic.Footnote48 As part of these efforts, the government reinstated youth leagues, including the NUYO, which became closely linked to the UPC and ‘almost interchangeable’.Footnote49 Laruni explains:

Members of the NUYO were used to intimidate opposition party members and civilians who were deemed to be unsympathetic to the administration. Despite the fact that NUYO was supposedly apolitical, youth members in fact became micro militias sent out to implement government directives and intimidate political opponents.Footnote50

Enshrined in Uganda’s 1995 constitution, the quota system mandates that youths – defined as any person aged between 18 and 30 – are represented by five members of parliament. This includes one representative (aged under 30) from each of the four regions of Uganda, and one National Youth MP (who should also be a woman). At the multi-tiered local council level, youth are represented in each district and each sub-county by two youth councillors, one male and one female, who link the Local Council and National Youth Council system (which replaced NUYO in 1993).Footnote52 The NYC is a statutory body which has responsibility for ‘organise(ing) the youth of Uganda in a unified body’, ‘encourag(ing) the youth in activities that are of benefit to them and the nation’, and ‘protect(ing) the youth against any kind of manipulation’.Footnote53 Representation of youth in Ugandan political structures under the NRM therefore came ‘as part and parcel of its corporatist strategy’ under the no-party system,Footnote54 a strategy that significantly and systematically weakened independent organizing outside the state.Footnote55

Like the regimes that came before it, the NRM has continued to rely on structural efforts to control and co-opt youth, pairing them with wide-ranging tactics some of which are longstanding (such as initiating youth groups) and others which are comparatively new (such as social media strategies).

The capture of youth as a political constituency

Considering this historical context, we draw on our fieldwork and news reports to explore youth campaigning during the 2021 election, and more specifically, how NRM strategies and tactics to co-opt ‘youth’ interface with historically-rooted methods of regime consolidation more broadly.

These include: the political organization of youth as a ‘special interest group’ paired with tactics of youth mobilization; economic opportunities for allegiance as well as ‘party switching’ in the context of embedded patronage; and social media tactics against the backdrop of powerful narratives that link social order and prosperity to a culture of gerontocracy. These strategies and tactics rely on homogenous constructions of the ‘youth’ category by the NRM, but also cannot be understood apart from the agency and choices made by young people as they navigate daily realities in a context of limited economic opportunity and profound economic precarity.

Political organization of youth as a special interest group: political patronage and party-based handouts

While the NRM’s youth policies may appear progressive, scholars have noted that their gift-like nature make youth particularly susceptible to patronage politics.Footnote56 Indeed, state mandated youth positions are dominated by young elite NRM members, and the centralization and standardization of channels for youth engagement in political and policy processes has provided fertile ground for NRM patronage and agenda setting amongst the youth demographic.Footnote57 The Uganda Youth Network, a civil society group has argued:

[Though youth quotas] provide an opportunity for youth to articulate their interests in the national legislative body, fusion of interest group with the government creates opportunities for co-option of youth leadership by the government. Under such contexts, the youth as an interest group cannot challenge the status quo in terms of power relations that define their vulnerability in the first place.Footnote58

The political impacts of the special interest logic are evidenced in Parliament as well as the National Youth Council (NYC). For instance, pressing issues of national significance become siphoned off as ‘youth’ issues and problems for youth MPs to deal with. Young Ugandans lament the failure of youth MPs to address key issues including un- and under-employment, the casualization of labour, poor working conditions, and high school fees.Footnote60 This is convenient for NRM politicians who also frame these concerns, and failures to address them, as problems for youth MPs, rather than national priorities.Footnote61

Meanwhile, the NYC, which claims to be an independent ‘umbrella organization’ of ‘all youth in Uganda between the ages of 18–30’,Footnote62 reportedly has ‘no input into programmes of government and are very easily compromised by government’.Footnote63 In fact, rather than represent the youth to government, NYC youth regularly use their platform to voice support for the NRM. For instance, in 2015, NYC representatives, referring to themselves as ‘pro-Museveni youth’ petitioned the Constitutional Court to remove presidential age limits.Footnote64 The extent of regime co-option of the NYC was evident during the general election campaign, when the NRM reportedly disbursed 50,000 Uganda shillings (approximately 10 GBP) to each village youth council (or 3.5 billion Uganda shillings; 709,600 GBP) to buy airtime ‘to reach out to NRM youth supporters’ and to ‘disseminate the party manifesto’.Footnote65 Days ahead of the general election, NYC chairman Jacob Eyeru, who was also chairperson of the NRM National Youth mobilization team, told journalists that ‘only the NRM … has highlighted proper plans’Footnote66 for the youth, which ‘should be the basis of casting votes in preference of one candidate over the other’.Footnote67 In a thinly veiled attack against Bobi Wine and the NUP, he continued ‘it is unfortunate to hear some politicians claiming to fight for, represent, and lead the youth without revealing what they have planned for them’.Footnote68

Under the NRM, elections and political campaigns are an important ‘avenue … for economic opportunity’, helping attract support from jobless youth.Footnote69 In 2016, there were over 1.7 million elective offices up for grabs across the country, making the political class five times larger than the civil service and army.Footnote70 For those pursuing employment through elected office, the NRM is a ‘natural choice’ and ‘simply the most attractive option’ for ‘aspiring young’ politicians because of better campaign finance than opposition parties; and further opportunities for patronage.Footnote71 One candidate for youth councillor explained the costs of running for office as a non-NRM candidate:

I was an independent candidate during the youth campaigns 2011 for my current position competing with an NRM candidate funded by a party who bought votes for cash and sugar and soap to voters. I also did the latter. Those elections left me broke and in debt so I had to sell my two motorcycles. Today – four years later – I am still in debt.Footnote72

A number of youth members of Parliament have been sucked into the system of patronage and despite the promising beginning at the start of their term; they have now become agents for state orchestrated patronage, being cited in the media for advancing issues that pose a threat to democracy and the entire policy engagement process at large.Footnote76

In addition to political patronage, the NRM regime is adept at offering economic incentives to young people during elections, such as short-term employment, loans and cash hand-outs. For instance, youth are often recruited as election workers, special police constables, crime preventers (especially in 2015–2016), and youth brigades.Footnote79 Amongst young, economically precarious men, this is seen as ‘an opportunity’ even though they become engaged in supporting the re-election of a regime they may oppose.Footnote80 Meanwhile, targeted economic incentives for youth include government loan schemes, such as the Youth Livelihood Fund (YLF), which purport to promote a ‘culture of self-employment’ through micro-finance, but are popularly viewed as a vehicle for party-based handouts during election periods, and often interpreted by recipients as a ‘gifts’.Footnote81 Straightforward cash handouts have also become ‘an increasingly standard way of tying constituencies to the regime’.Footnote82 Titeca notes that after registering heavy losses in Kampala in the 2016 elections, Museveni donated up to 300 million UGX (67,500 GBP) at a time to selected youth savings cooperatives; in September 2016 alone, he gave an estimated 1.6 billion UGX (360,000 GBP) to Kampala youth groups.Footnote83 Government scholarships are also widely discussed. One youth commented, ‘Young people in this region, particularly the FRONASA youth, we have benefited in one way or the other from the party in terms of scholarships.’Footnote84 As one NRM youth explained: ‘There are many strategies, not only money, but money is among things that when given, you cannot refuse’.Footnote85 Even if only reaching the few, these generous gifts give hope to many.

Political opportunism? Pressure groups and public defections

Both independently and within NRM structures, so-called youth ‘pressure groups’ have emerged to attract regime patronage during election periods. They might offer performances of allegiance to the NRM by publicly declaring a change in political affiliation from opposition parties.Footnote86 The NRM Poor Youth for example, originally formed to back former prime minister Amama Mbabazi for the presidential nomination in 2015, but defected to NRM after a meeting at an upscale hotel in Kampala, where members of the group were allegedly ‘paid 1.5 million and were promised more money’.Footnote87 Khisa argues that such ‘youth networks’ have been ‘a major strategic group that Museveni has used when seeking renewal’ and that the NRM Poor Youth were adept at exploiting their value to prospective presidential candidates: ‘dining with Museveni at state house one day and meeting Mbabazi at his residence the next’.Footnote88

In northern Uganda, several groups have emerged from within the local NRM party youth structures, including the NRM Social Media Activists, the NRM Party After Party, the NRM 100% Youth Coalition, NRM Concerned Youth, the Bazukulu NRM Youth (grandchildren of the president), the NRM FRONASA Youth, and Aweno Pe Kilaro Ki Rwed Tol, which references an Acholi proverb that counsels people not to claim a thing that does not belong to them. Group members described themselves as NRM ‘cadres’, and explained that they joined the groups to receive financial benefits (referred to as ‘facilitation’) as well as recognition for ‘doing a very good job’.Footnote89 As Perrot argues, ‘micro-economic politics’ at this level is ‘not simply a symbol of electoral opportunism but part of a routine economic posture in a context of straddling lines between the economic and political spheres’.Footnote90

The NRM Social Media Activists, for example, formed through ‘sacrificing’ in 2018.Footnote91 After demonstrating that they could mobilize support among young people across social media platforms, they were recruited by senior NRM officials who formalized support for the group. As one respondent explained, during the 2021 election, the group was responsible for ‘sell(ing) the idea of the NRM party to different people through the media, we just [use] NRM apps, we use WhatsApp, we use Twitter, we use Facebook. Then we also go on radio stations and we talk to people, we convey the messages of NRM, we convey the manifesto of the NRM’.Footnote92 The group also engaged in more traditional forms of mobilization, ‘moving to the villages’, organizing dialogues and trying to ‘change the mindset of people towards the NRM’.Footnote93 Other groups such as the NRM Bazukulu, did work that was ‘assigned by the party’, for example, spreading messages about ‘the good of the government and the good of the NRM’ and preparing campaign venues and tidying up after events.Footnote94

The NRM Youth League leadership in Gulu referred to all the local NRM youth pressure groups as their ‘children’, reflecting both the material patronage exchange among these parties, and a discourse that relates this to generationally structured family ties.Footnote95 Pressure group leaders reportedly received a variety of gifts from NRM higher ups, including cars, motorcycles, recommendations for employment, and permanent appointments within the party and civil service. At the same time, in a broader context of under-employment and economic precarity, some pressure group members also expressed reservations about these dynamics, whereby ‘the party at national level has not channelled any resources towards the development of ideology … we get money during the campaign periods and after the campaigns there is no money, you remain redundant’.Footnote96 In these periods, the groups may ‘de-activate’ entirely, or they may lobby NGOs for support but ‘outside the operation of the party’, meaning that the group takes on a different name or identity.Footnote97 Importantly, NRM youth leadership continues to provide moral and organizational support to the groups under these different guises in a way that ‘blurs the line between the political realm, and the daily life of people’.Footnote98

Party-switching is a longstanding political tactic in Uganda; one that the NRM has used to great effect. Sometimes this plays out in the national press because it is associated with high-level political figures. During the 2021 campaign season, Museveni poached popular musicians with wide youth appeal who had been working closely with the NUP. He appointed Bobi Wine’s deputy, known as Butcherman as Presidential Advisor on the Ghetto and musician Catherine Kusasira as Presidential Adviser for Kampala Affairs.Footnote99 As NUP Mukono municipality MP Betty Bakireke Nambooze said:

Using the carrot, Museveni is now recruiting the city riff-raffs and musicians not because of the value they bring to his NRM but because he wants Bobi to be fought by his own … So when General Museveni saluted Butcherman, he meant it.Footnote100

While the media publicizes high-level defections, party-switching at the grassroots level is ‘at least as important in terms of party organisation and opposition disorganisation’.Footnote103 In December 2020, at least 500 NUP supporters, along with their leaders in Gulu and Nwoya Districts, allegedly defected to the NRM; the following month, 780 NUP co-ordinators in Agago district reportedly did the same.Footnote104 Behind the scenes negotiations came to light after the former Nwoya district NUP registrar lamented that the NRM had reneged on an agreement to provide 30 million Ugandan shillings (approximately 6,000 GBP) to Nwoya’s 11 sub-counties to support economic activities in exchange for the defection of 11,000 NUP youth.Footnote105 He also reportedly said that the president had pledged ‘sh50 m and two double cabin pickups’ to help former NUP agents to demobilize youth from supporting NUP.Footnote106 In Gulu, the NRM Youth leadership explained that a core part of their role was ‘weeding out’ NUP supporters, by getting them positions on youth councils and offering other benefits: ‘there are so many that we talk to’, explained one, ‘we really engaged them … and we weakened them’ and now they are ‘working towards continuing to extend the gospel of NRM to the non-converts’.Footnote107

Social media, society, and culture: Mzee and his Bazukulu

Coverage of social media usage ahead of the elections implied the government was on the defensive, using measures like the social media shutdown 48 h before the presidential vote. It was widely argued that social media would benefit the opposition, empowering (young) people to circumvent traditional media outlets that are either state-owned or heavily circumscribed by legislation and commercial advertising interests.Footnote108 Less explored is how the NRM successfully used social media for its own propaganda purposes. As Morozov argued in relation to the Arab Spring uprisings ‘the idea that the internet favours the oppressed rather than the oppressor is marred by … cyber-utopianism: a naïve belief in the emancipatory nature of online communication that rests on a stubborn refusal to acknowledge its downside’.Footnote109 Like other authoritarian regimes, the NRM tried to manipulate voters across various social media platforms via ‘false information, false digital identities, fake accounts, fabricated context, [and] fake news’.Footnote110 Bans on physical gatherings due to COVID-19 restrictions made these tactics all the more significant.

Analysis of social media hashtag #SecureYourFuture by the Digital Forensic Research Lab concluded the existence of ‘a coordinated campaign to promote Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’ ahead of the election.Footnote111 Numerous cases of ‘coordinated inauthentic behaviour’ led to both Facebook and Twitter to suspend over 100 pro-Museveni and pro-government accounts.Footnote112 These fake and duplicate accounts were allegedly linked to the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology and engaged in co-ordinated tweeting in support of Museveni’s campaign as well as efforts to discredit the opposition, including through rape allegations designed to go viral.Footnote113

The African Institute for Investigative Journalism suspected the government may be co-ordinating youth to run fake accounts.Footnote114 While the government denied this, NRM youth cadres were certainly engaged in social media activism. Across the Acholi region for example, prior to the elections, the NRM constituted a team of social media activists. The group was composed of both youth and senior cadres who underwent training at Kyankwanzi National Leadership Institute.Footnote115 The group was tasked with sending pro-NRM messages to voters across the region via social media platforms.Footnote116 These messages were directed by senior party members who regularly met with the social media activists at hotels in Gulu.Footnote117 WhatsApp groups were also used as a key communication strategy by the NRM. Several WhatsApp groups were formed before the elections and designed to appeal to young voters. While the majority were national groups, they also had membership at the district level such as the Northern Youths Dialogue and the 100% Youth Forum.Footnote118 While we cannot establish the extent to which this translated into votes for the NRM, it illustrates the NRM’s efforts to shape online conversations and digital spaces.

In addition to social media, ‘old media’ remained an important battle ground in the 2021 campaign. In the Acholi region, the NRM reportedly bought peak airtime across popular radio stations to exclude the opposition. High-level NRM officials briefed station managers on communication strategies. The regime recruited youth activists to appear on radio shows to advance the NRM manifesto and answer call-in questions from the public. They rehearsed carefully crafted messages exploiting regional divisions that have long fragmented youth, for example, warning listeners that Bobi Wine was a Muganda sectarian and that his election would push the north back into conflict.

Narrative framings: protecting the ‘children’ of the nation from existential insecurities

The NRM’s political, economic and cultural strategies and tactics are underpinned by a particular construction of the ‘youth’ category, rooted in patrimonial and gerontocratic visions of social and political order. Also evident in the policies of Obote and Amin, youth are narrated as the lifeblood and quintessence of the nation. They are expected to be obedient and to honour the social and economic obligations placed upon them, and are promised rewards in return. Museveni, for example, calls young voters his bazukulu or ‘grandchildren’, promising to secure the future of young people if they vote him in: ‘Youth will directly get funding’ he tweeted ‘ … I urged the youth to remain disciplined, spiritual, ideological and productive. #SecuringYourFuture’.Footnote119 In turn, Museveni adeptly plays the patriarchal Mzee, with many young Ugandans affectionately referring to him by his nickname, ‘Sevo’.Footnote120 In a playful Twitter posting that went viral during the COVID-19 lockdown in August 2020, Museveni wrote ‘After work last night, I challenged my Bazukulu to an indoor workout. We did Forty Push-ups’, accompanied a video of the exercise routine with electronic music playing in the background.Footnote121 His carefully crafted image as elder and father of the nation, and youth as his grandchildren, reinforces a narrative that he is responsible for steering the ship and his ‘youth’ for providing its fuel.

A second key narrative, related to the first, emphasizes the NRM as sword and shield – and Museveni as the sole leader who can ensure peace and economic development. This narrative is poignantly reflected in the messages of youth pressure groups and defectors in northern Uganda, with its relatively recent experience of civil conflict. For example, the Chairman of the National Youth Council, Jacob Eyere, explained NRM victories across northern and eastern regions as follows: ‘If you come from the north and east you will understand that a big achievement of peace has been brought. For 20 years those regions were engulfed in war’.Footnote122 In these areas, the NRM youth activists presented the NUP as threatening, drawing on securitized narratives of unruly, unpatriotic young men as promoted by the NRM regime. One NRM youth activist explained ‘we don’t believe in defiance … the youth of northern Uganda, we know what was experienced in the past years, we don’t believe in wars’.Footnote123 Another said that, ‘the way NUP came in, it scared very many people, so the northerners just picked up our slogan that we are tired of war because most people associated the NUP with violence and Bobi Wine seemed more violent, people deemed them as war mongers capable of occasioning unrest in the country’.Footnote124

This narrative includes concerns about economic security, attributing poverty in the north and east of Uganda to a historic opposition to the NRM and Museveni. As one youth activist explained:

The opposition has become like a time-bomb in Acholi sub-region and have misled the people a lot … look at areas where opposition have really dominated … there is a lot of poverty, infrastructure is down, education is down, medical services are down.Footnote125

The rumour that youths were bribed is all not true, these youths just … realized that the NRM still has a bright future. That is why I always tell people that when you take a goat and a leopard in the market, most people will be attracted to the leopard but when evening comes, they end up taking the goat at home because they know that the leopard can devour them … that is why our members who were in NUP returned to our party as NRM, they felt that NRM has a bright future.Footnote126

Conclusions: moving beyond the disengaged/dangerous dichotomy

Why do youth mobilize politically in some contexts but not in others? Many existing studies focus on youth’s political engagement (or lack thereof), or their willingness to seek political change through institutions rather than violence. To probe these explanations, this article has examined youth political activity in Uganda’s 2021 elections as a case that defied analysts’ expectations. Youth in Uganda are a large constituency, and one that has been disenfranchised and faced limited economic, social, and political opportunities. With the rise of Bobi Wine, many expected that a ‘youth wave’ would raise a meaningful challenge to the status quo. Our study, however, identifies diverse and historically rooted strategies and tactics that interface with the broader political economy to obstruct the emergence of a youth political constituency in Uganda. These findings help explain the electoral results in Uganda in 2021, illustrating both how the NRM’s approach to youth draws on past structures, practices, and narratives, as well as how the NRM has further innovated. The findings emphasize how political, economic, and cultural factors are intertwined and reinforcing, such that political opposition – and especially those purporting to represent youth – must swim against a strong current.

Our analysis identified two patterns. First, as many scholars have remarked upon in the current moment, there is a clear generational cycle when younger generations realize they may never graduate to positions of power. While this is notable in Uganda today, it is also not novel: Ugandans faced racial and age-based barriers to social, economic, and political progression during colonial rule. Young people were again dissatisfied when Obote returned to power in 1980 reinstating loyal colleagues to positions of power just as a new generation had anticipated their recompense. In both these instances, youth were unable to mobilize as a collective, instead remaining the handmaiden to elite transitions in power.

Second, the study reveals longstanding and well-developed structures, practices, and narratives that have facilitated the mobilization and demobilization of youth. First, political structures have been designed to fragment national organization of youth, subsuming youth representation under regime authority and regional divisions. Making youth an interest group has reinforced patronage logic and allowed the ruling regime significant influence over the direction and activities of youth politics. The broader political patronage system has significantly depoliticized key activities like party-affiliation and voting, as young un- and underemployed people seek to navigate a bleak economy. These strategies reinforce and reiterate popular narratives related to social and political order that favour continued incumbent gerontocratic control.

The overall picture is one in which the elite have long seen youth as a potential political constituency – and as such, have both feared and valued youth. Governing Uganda has thus long required rulers to account for the potential of youth as a political force, and as a result, sequential regimes have developed complex strategies to prevent this very eventuality. At the same time, our findings highlight how young people across Uganda, often trapped in a state of economic precarity, actively seek out and engage in opportunities for patronage and advancement offered by the NRM, particularly during election periods. These efforts, however, take the form of the structure within which they take place, obstructing collective political mobilization. Taken in its historic context, the findings show that the fanfare about Bobi Wine and Uganda’s youth vote was premature, given the existing structural conditions that hamper youth political organization and mobilization nationally. They also clearly demonstrate the need to look beyond rallies and rhetoric to identify whether the conditions are in place to allow youth to emerge as a politically salient category.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers, the JEAS editors, and Sam Wilkins and Richard Vokes for extremely helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Titeca, “Uganda: Museveni’s Struggle”; Reuss and Titeca, “This is Why Bobi Wine Constitutes an Unprecedented Threat”; Hamza Mohamed, “Will Bobi Wine Derail Museveni’s Sixth Term Bid?” Al Jazeera, January 11, 2021, sec. News. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/1/11/uganda-election-will-bobi-wine-derail-musevenis-sixth-term-bid; Emmanuel Akinwotu and Samuel Okiror, “Ugandans Go to Polls in Election Pitting Museveni against Pop Star MP.” The Guardian, January 14, 2021, sec. Global development. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jan/14/uganda-polls-election-campaign-violence-museveni-wine.

2 Further, a mere 24% of youth are estimated to be in wage-paying jobs. Ahaibwe and Mbowa, “Youth Unemployment Challenge in Uganda.”

3 Wilkins, Vokes, and Khisa, “Briefing.”

4 Kujeke “Uganda Stifles the Youth Vote a Year Ahead of Elections.”

5 Grasse et al., “Opportunistic Repression.”

6 This was the narrowest win yet for Museveni, who previously won the presidency with an estimated 75% of the vote in 1996; 69% in 2001; 59% in 2006; 68% in 2011; and 60% in 2016. The election results were also strongly contested by the opposition, and there is evidence of vote rigging and voter suppression (see Wilkins et al., “Briefing.”).

7 Oosterom, “Youth Engagement in the Realm of Local Governance,” 9.

8 Uganda’s National Youth Policy defines youth as between 18 and 30 years of age – however, other institutions use different age ranges, for instance, the African Union defines youth as between 15 and 35 years, while the United Nations uses 18–24 years.

9 Wilkins, Vokes, and Khisa, “Briefing.”

10 Seawright and Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques,” 297.

11 According to data from recent Uganda National Household Surveys, ‘over 87% of youth in Uganda work in insecure, low income and often unsafe informal-sector jobs, or in family income generation activities with little or no pay at all’, see Mutenyo et al., “Work and Income,” 2; and Mallett et al., “Youth on the Margins.”

12 Mallet et al., “Youth on the Margins,” iv.

13 The start and end dates to this conflict are complex, please see Allen and Vlassenroot, The Lord’s Resistance Army, 7–10 for more details.

14 Resnick and Casale, “Young Populations in Young Democracies,” 1175.

15 Honwana, “Enough Is Enough!”

16 Sukarieh and Tannock, Youth Rising? 858–59.

17 Baaz and Stern, “Making Sense of Violence”; Peters and Richards, “‘Why We Fight’”; Vlassenroot et al., “Navigating Social Spaces.”

18 Ndlela and Mano, Social Media and Elections in Africa; Sukarieh and Tannock, Youth Rising?

19 Sukarieh and Tannock, Youth Rising? 107.

20 Musarurwa, “Closed Spaces or (in)Competent Citizens?” 177.

21 Resnick and Casale, “Young Populations in Young Democracies”; see also Bollen, “Why Ugandan Youth Don’t Vote”; Scott et al., “Punching Below Their Weight”; Oyedemi and Mahlatji, “The ‘Born-Free’ Non-Voting Youth”; Mac-Ikemenjima, “Violence and Youth Voter Turnout”; Musarurwa, “Closed Spaces or (in)Competent Citizens?”

22 Resnick and Casale, “Young Populations in Young Democracies,” 1179.

23 Ibid., 1173.

24 Bollen, “Why Ugandan Youth Don’t Vote.”

25 Kujeke “Uganda Stifles the Youth Vote.”

26 Ibid.

27 Comaroff and Comaroff, “Reflections on Youth,” 268.

28 Ibid., 273.

29 Laruni, “From the Village to Entebbe,” 87.

30 Ibid., 89.

31 Ibid., 88.

32 Ibid.

33 Mujaju, “The Demise of UPCYL,” 294.

34 Taylor, “Affective Registers of Postcolonial Crisis,” 546.

35 Mujaju, “The Demise of UPCYL,” 296.

36 Daily Monitor, “How UPC Struggled to Deal with Youth Wing Menace.” June 28, 2020. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/magazines/people-power/how-upc-struggled-to-deal-with-youth-wing-menace-1897132

37 Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, “The National Youth Policy,” 5.

38 Mujaju, “The Demise of UPCYL,” 303.

39 Ibid., 303.

40 Barya, “Performance of Workers and Youth,” 6.

41 Langlands, “Students and Politics in Uganda,” 9.

42 Ibid., 6.

43 Ibid., 9.

44 Laruni, “From the Village to Entebbe,” 290.

45 Peterson and Taylor, “Rethinking the State in Idi Amin’s Uganda,” 69.

46 Laruni, “From the Village to Entebbe,” 290.

47 Ibid., 290.

48 Ibid., 290.

49 Ibid., 291.

50 Ibid., 291; also see Leon Dash, “Violence Poisons Political Process Within Uganda.” Washington Post, December 1, 1983. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1983/12/01/violence-poisons-political-process-within-uganda/1d4a504d-d186-4100-ba19-971dbaa4c577/

51 Tidemand, “The Resistance Councils in Uganda,” 79–80.

52 Saito, “The Representation of the Disadvantaged,” 113.

53 National Youth Council, “About Us,” Kampala, Uganda, 2021. https://www.nyc.org.ug/about.

54 Barya, “Performance of Workers and Youth,” 6.

55 Okiring, “Effective Youth Participation in Policy Processes,” 45.

56 Ibid., 47.

57 For example, the 2016 Western Youth MP race pitted Amanya Tumukunde (son of Gen. Henry Tumukunde) against Mwine Rwamirama (son of Lt Col Bright Rwamirama). See Daily Monitor. “Tumukunde Shot in Fort Portal Youth MP Polls Brawl.” March 1, 2016. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/tumukunde-shot-in-fort-portal-youth-mp-polls-brawl-1642036.

58 Uganda Youth Network and African Youth Development Link 2014: “Representative Democracy and Special Interest Group Representation”, July 2014, cited in Bayra, 10.

59 Okring, “Effectve Youth Participation in Policy Processes.”

60 Barya, “Performance of Workers and Youth,” 16.

61 Ibid.

62 Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development “The National Youth Policy,” 7.

63 Barya, “Performance of Workers and Youth,” 20.

64 Daily Monitor, “Pro-Museveni Youth Want Age Limit Lifted.” March 30, 2015. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/pro-museveni-youth-want-age-limit-lifted-1605776.

65 The Independent, “NRM to Spend Billions on Village Youth Councils.” January 5, 2021, sec. NEWS. https://www.independent.co.ug/nrm-to-spend-billions-on-village-youth-councils/

66 Busein Samilu, “National Youth Council Slams Opposition Candidates for Sidelining Youth in Manifestos.” Chimp Reports, January 11, 2021, sec. News. https://chimpreports.com/national-youth-council-slams-opposition-candidates-for-sidelining-youth-in-manifestos/.

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Angelo Izama, “The Battle for Uganda’s ‘Museveni Babies.’” Foreign Policy, November 17, 2015. http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/11/17/uganda-museveni-babies-election-violence/?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=New%20Campaign&utm_term=%2AEditors%20Picks

70 Ibid.

71 Muriaas and Wang, “Executive Dominance.”

72 Black Monday, “Voter Bribery: Youth Speak Out,” April 26, 2015. https://uganda.actionaid.org/sites/uganda/files/black-monday-newsletter-issue-no.26-april-2015.pdf.

73 Muriaas and Wang, “Executive Dominance.”

74 Interview a, 28 January 2021.

75 Interview b, 28 January 2021; Interview 2 February 2021.

76 Okiring, “Effective Youth Participation in Policy Processes,” 52.

77 Mubatsi’s Thoughts, “Reduced to a Kneeling Generation.” Blog, May 30, 2014. http://habati-am.blogspot.com/2014/05/reduced-to-kneeling-generation.html.

78 Okiring, “Effective Youth Participation in Policy Processes,” 49.

79 Tapscott, “Where the Wild Things Are Not.”

80 Ibid.; Tapscott, Arbitrary States.

81 Ahaibwe and Mbowa, “Youth Unemployment Challenge in Uganda”; Ronald Seebe, “Namutumba Youth Fail to Return YLP Money.” Daily Monitor, December 2, 2020. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/namutumba-youth-fail-to-return-ylp-money-3216486; Titeca, “Its Own Worst Enemy?”; Suzan Nanjala. “Gulu Youth Fail to Return YLP Money.” Daily Monitor, March 5, 2021. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/gulu-youth-fail-to-return-ylp-money-3312826.

82 Titeca, “Its Own Worst Enemy?” 2.

83 Ibid.

84 Interview, 2 February 2021.

85 Interview c, 28 January 2021.

86 Perrot, “Partisan Defections in Contemporary Uganda,” 715.

87 NTV Uganda, “‘NRM Poor Youth’ abandon Mbabazi, join NRM” [1m52s], August 20, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8GZASXtRRU

88 Khisa, “Managing Elite Defection in Museveni’s Uganda,” 741–42.

89 Interview a, 28 January 2021.

90 Perrot, “Partisan Defections in Contemporary Uganda,” 720.

91 Interview a, 28 January 2021.

92 Ibid.

93 Ibid.

94 Interview c, 28 January 2021.

95 Interview b, 28 January 2021.

96 Ibid.

97 Ibid.

98 Perrot, “Partisan Defections in Contemporary Uganda,” 719.

99 Baker Batte, “Inside Museveni’s War on the Ghetto.” The Observer, November 6, 2019. https://observer.ug/news/headlines/62550-inside-museveni-s-war-on-the-ghetto.

100 Ibid.

101 Perrot, “Partisan Defections in Contemporary Uganda,” 717.

102 Ibid., 717.

103 Ibid., 718.

104 The Independent, “Opposition Parties Accuse NRM of Stage-Managing Defections in Acholi.” January 7, 2021. https://www.independent.co.ug/opposition-parties-accuse-nrm-of-stage-managing-defections-in-acholi/.

105 Emmanuel Busingye, “NRM Cash Splits Acholi NUP Defectors.” Ekyooto Uganda (blog), December 22, 2020. https://ekyooto.co.uk/2020/12/22/nrm-cash-splits-nup-defectors/.

106 Ibid.; URN. “Caught off Guard: Defectors Fail to Prove Opposition Membership.” The Observer, December 28, 2020. https://observer.ug/news/headlines/67931-caught-off-guard-defectors-fail-to-prove-opposition-membership.

107 Interview b, 28 January 2021.

108 Geoffrey Ssenoga. “Social Media Seized the Narrative in Uganda’s Election. Why This Was Good for Democracy.” The Conversation (blog), January 12, 2021. https://theconversation.com/social-media-seized-the-narrative-in-ugandas-election-why-this-was-good-for-democracy-153107.

109 Morozov, The Net Delusion, xiii.

110 Samuel-Stone, “Digital Voter Manipulation,” iv.

111 Ibid., 2.

112 Ibid., 3.

113 Ibid., 4.

114 Ibid., 3.

115 Interview b, 28 January 2021

116 Ibid.

117 Author two fieldnotes, January 2021.

118 Ibid.

119 @KagutaMuseveni (Museveni, Yoweri K). “I Met Youth Leaders from the Bugisu Sub-Region at Mbale SS Grounds. We Discussed among Other Issues; Youth Welfare, and Economic Empowerment. I Encouraged the Youth to Get Involved in Modern Means of Work. #SecuringYourFuture.” Twitter, November 25, 2020. https://twitter.com/KagutaMuseveni/status/1331643689777684481.

120 Patience Atuhaire. “Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni: How an Ex-Rebel Has Stayed in Power for 35 Years.” BBC News, May 10, 2021, sec. Africa. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55550932.

121 @KagutaMuseveni (Museveni, Yoweri K). “After Work Last Night, I Challenged My Bazukulu to an Indoor Work-out. We Did Forty Push-Ups. Just like I Have Always Advised, Even at Your Own Home, You Can Stay Safe, and Remain Fit and Healthy.” Twitter, August 5, 2020. https://twitter.com/kagutamuseveni/status/1290940769105252352

122 Atuhaire, “Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni,” op.cit.

123 Interview, 2 February 2021.

124 Interview a, 28 January 2021.

125 Interview a, 2 February 2021.

126 Interview c, 28 January 2021.

Bibliography

- Ahaibwe, Gemma, and Swaibu Mbowa. “Youth Unemployment Challenge in Uganda and the Role of Employment Policies in Jobs Creation.” Brookings, August 26, 2014. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/africa-in-focus/posts/2014/08/26-youth-unemployment-uganda-ahaibwe-mbowa.

- Allen, Tim, and Koen Vlassenroot, eds. The Lord’s Resistance Army: Myth and Reality. London: Zed Books, 2010.

- Baaz, Maria Eriksson, and Maria Stern. “Making Sense of Violence: Voices of Soldiers in the Congo (DRC).” The Journal of Modern African Studies 46, no. 1 (2008): 57–86.

- Barya, John-Jean. Performance of Workers and Youth Members of Parliament in Uganda 1995-2015. Kampala: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2017. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/uganda/14399.pdf.

- Bollen, Paige. “Why Ugandan Youth Don’t Vote.” MITGov/Lab, March 2016. https://mitgovlab.org/updates/why-ugandan-youth-dont-vote-learning-note-9/.

- Comaroff, Jean, and John Comaroff. “Reflections on Youth, from the Past to the Postcolony.” In Frontiers of Capital: Ethnographic Reflections on the New Economy, edited by Melissa S. Fisher, and Greg Downey, 267–281. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Grasse, Donald, Melissa Pavlik, Hilary Matfess, and Travis B. Curtice. “Opportunistic Repression: Civilian Targeting by the State in Response to COVID-19.” International Security 46, no. 2 (2021): 130–165.

- Honwana, Alcinda. “Enough Is Enough!: Youth Protests and Political Change in Africa.” In Collective Mobilisations in Africa. Enough Is Enough, edited by Kadya Tall, Marie-Emmanuelle Pommerolle, and Michel Cahen, 45–65. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

- Khisa, Moses. “Managing Elite Defection in Museveni’s Uganda: The 2016 Elections in Perspective.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 4 (2016): 729–748.

- Langlands, Bryan. “Students and Politics in Uganda.” African Affairs 76, no. 302 (1977): 3–20.

- Laruni, Elizabeth. “From the Village to Entebbe: The Acholi of Northern Uganda and the Politics of Identity, 1950-1985.” PhD in History, University of Exeter, 2014. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/16003

- Mac-Ikemenjima, Dabesaki. “Violence and Youth Voter Turnout in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Contemporary Social Science 12, no. 3–4 (2017): 215–226.

- Mallett, Richard. Teddy Atim and Jimmy Opio, “Youth on the Margins: In Search of Decent Work in Northern Uganda”. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (2016). https://securelivelihoods.org/publication/youth-on-the-marginsin-search-of-decent-work-in-northern-uganda/?resourceid=425

- Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development. “The National Youth Policy: A Vision for Youth in the 21st Century.” Kampala, Uganda, 2001. https://www.youthpolicy.org/national/Uganda_2001_National_Youth_Policy.pdf.

- Morozov, Evgeny. The Net Delusion: How Not to Liberate The World. London: Penguin, 2011.

- Mujaju, Akhki B. “The Demise of UPCYL and the Rise of NUYO in Uganda.” African Review 3, no. 2 (1973): 291–307.

- Muriaas, Ragnhild, and Vibeke Wang. “Executive Dominance and the Politics of Quota Representation in Uganda.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 50, no. 2 (2012): 309–338.

- Musarurwa, Hillary Jephat. “Closed Spaces or (in)Competent Citizens? A Study of Youth Preparedness for Participation in Elections in Zimbabwe.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 56, no. 2 (2018): 177–194.

- Mutenyo, John, Faisal Buyinza, Vincent Ssenono, and Wilson Asiimwe. “Work and Income for Young Men and Women in Africa: Case of Uganda”, African Economic Research Consortium Policy Brief (2022) https://includeplatform.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/GSYE-005-UGANDA.pdf.

- Ndlela, Martin, and Winston Mano, eds. Social Media and Elections in Africa, Volume 1: Theoretical Perspectives and Election Campaigns. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

- Okiring, Helena. “Effective Youth Participation in Policy Processes.” In Youth and Public Policy in Uganda, 40–65. Youth Policy Press and Society for International Development, 2015. http://www.youthpolicypress.com/pdfs/Uganda_20150914.pdf

- Oosterom, Marjoke. “Youth Engagement in the Realm of Local Governance: Opportunities for Peace?” IDS Working Paper. Institute of Development Studies and Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, 2018.

- Oyedemi, Toks, and Desline Mahlatji. “The ‘Born-Free’ Non-Voting Youth: A Study of Voter Apathy Among a Selected Cohort of South African Youth.” Politikon 43, no. 3 (2016): 311–323.

- Perrot, Sandrine. “Partisan Defections in Contemporary Uganda: The Micro-Dynamics of Hegemonic Party-Building.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 4 (2016): 713–728.

- Peters, Krijn, and Paul Richards. “‘Why We Fight’: Voices of Youth Combatants in Sierra Leone.” Africa 68, no. 2 (1998): 183–210.

- Peterson, Derek R., and Edgar C. Taylor. “Rethinking the State in Idi Amin’s Uganda: The Politics of Exhortation.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 7, no. 1 (2013): 58–82.

- Resnick, Danielle, and Daniela Casale. “Young Populations in Young Democracies: Generational Voting Behaviour in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Democratization 21, no. 6 (2014): 1172–1194.

- Reuss, Anna, and Kristof Titeca. “This is Why Bobi Wine Constitutes an Unprecedented Threat to Museveni.” Democracy in Africa (blog), December 17, 2020. https://democracyinafrica.org/bobi_wine_threat_museveni/.

- Saito, Fumihiko. “The Representation of the Disadvantaged: Women, Youth and Ethnic Minorities.” In Decentralization and Development Partnership: Lessons from Uganda, edited by Fumihiko Saito, 101–124. Tokyo: Springer Japan, 2003.

- Samuel-Stone, Songa. Digital Voter Manipulation: A Situational Analysis of How Online Spaces Were Used as a Manipulative Tool during Uganda’s 2021 General Election. Kampala: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung and the African Institute for Investigative Journalism, 2921. https://www.kas.de/documents/280229/0/Digital+Voter+Manipulation+Report.pdf/910ccef1-3d4e-1f58-0d4c-70f0509a1e89?version=1.1&t=1624704090405.

- Scott, Duncan, Mohammed Vawda, Sharlene Swartz, and Arvin Bhana. “Punching below Their Weight: Young South Africans’ Recent Voting Patterns.” HSRC Review 10, no. 3 (September 2012): 19–22.

- Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 294–308.

- Sukarieh, Mayssoun, and Stuart Tannock. Youth Rising?: The Politics of Youth in the Global Economy. Routledge, 2015. https://www.routledge.com/Youth-Rising-The-Politics-of-Youth-in-the-Global-Economy/Sukarieh-Tannock/p/book/9780415711265.

- Tapscott, Rebecca. Arbitrary States: Social Control and Modern Authoritarianism in Museveni’s Uganda. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Tapscott, Rebecca. “Where the Wild Things are Not: Crime Preventers and the 2016 Ugandan Elections.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 4 (2016): 693–712.

- Taylor, Edgar Curtis. “Affective Registers of Postcolonial Crisis: The Kampala Tank Hill Party.” Africa 89, no. 3 (2019): 541–561.

- Tidemand, Per. The Resistance Councils in Uganda: A Study of Rural Politics and Popular Democracy in Africa, PhD thesis, Roskilde University, 1994.

- Titeca, Kristof. “Its Own Worst Enemy?: The Ugandan Government is Taking Desperate Measures to Control Rising Dissent.” Africa Policy Brief. Egmont Institute, 2019.

- Titeca, Kristof. “Uganda: Museveni’s Struggle to Create Legitimacy among the ‘Museveni Babies.’” University of Antwerp: Institute of Development Policy, 2019. https://medialibrary.uantwerpen.be/oldcontent/container2673/files/Publications/APB/36-Titeca.pdf.

- Vlassenroot, Koen, Emery Mudinga, and Josaphat Musamba. “Navigating Social Spaces: Armed Mobilization and Circular Return in Eastern DR Congo.” Journal of Refugee Studies 33, no. 4 (2021): 832–852.

- Wilkins, Sam, Richard Vokes, and Moses Khisa. “Briefing: Contextualizing the Bobi Wine Factor in Uganda’s 2021 Elections.” African Affairs 120, no. 481 (2021): 629–643.