ABSTRACT

This article develops the concept of citizenship moods to analyse citizens’ emotional (dis)engagements with the state in Uganda. Through a reflexive analysis of ethnographic and media material from 2019–2021, we claim that around the time of the 2021 elections, after 35 years of rule by Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement, the most prevalent moods among Ugandans were fear, contentment, cynicism, anger, hope, and despondency. Prior to the elections, hope soared, but this gave way to despondency following the state’s violent crack-down on opposition. Building on work on citizenship, affect, emotion, and politics, we theorise that citizenship moods are experienced both individually and collectively; coexist, transform, and fluctuate over time; and affect and are affected by political and societal change. In Uganda, a key change is the growth of intersecting ethnic, regional, generational, and class inequalities. Citizenship moods structure, transform, and vitalise the relationship between the state and its citizens, and analysing them contributes to imagining the possibilities of democratic change in Uganda and beyond. The article introduces a method of cartoon-powered sociopolitical analysis. The inherent attunement of cartoons to bodily postures and expressions enables analytical insight and effective communication of research results, and can contribute to advancing research justice.

Citizenship as a category of experience rather than merely a legal status is steeped in, productive of, and moulded by moods. In this article, we build on research on citizenship, and on affect and emotion in politics, to advance the notion of citizenship moods as a means for describing citizens’ emotional (dis)engagements with the state. Specifically, we trace Ugandan citizens’ experiences of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) state, and their perceptions both of the regime's success in protecting and providing for them, and of their own ability to hold the state accountable. Our means to this end – cartoon-powered socio-political analysis – provides a novel way of capturing and disentangling citizenship moods during what we refer to as the ‘late Museveni era’, given that president Yoweri Museveni is (officially) 76 years old at the time of writing, and has already been in power for more than 35 years. Our method explicitly integrates the first author's practice as a cartoonist and political commentator into the iteratively interpretive process of collaborative analysis, and conveys our belief that scholarly work is strengthened when we acknowledge that our positionalities, commitments and moods shape our analysis.

In the general elections of 2021, Museveni’s NRM secured another term amid violence and widespread allegations of election irregularities. During the period leading up to and the months following the elections, we argue that the most prevalent moods among Ugandan citizens were anger, fear, cynicism, despondence, contentment, and hope. As we will show, such moods are not clear-cut and mutually exclusive, but can be momentarily ‘captured’ so as to show the complex ways in which they overlap and coexist. Following anthropological analyses of affective states, our interest is to explore how moods structure the space between the state and citizenry, how they emerge and evolve amid the historically embedded relationships between the state and citizens in Uganda, and how they influence the possibilities of democratic change in the country.

We begin by sketching how our concept of citizenship moods builds on and contributes to existing literature on citizenship and affect. We then introduce cartoon-powered socio-political analysis as a method that captures the somewhat elusive nature of moods, and that allows for increasing the communicability and social relevance of research. Thereafter, we delineate aspects of Ugandan history and contemporary societal dynamics that we see as particularly relevant for understanding citizenship moods in the country. In light of this background, we present a combined textual/graphic analysis of prevailing citizenship moods and their dynamism in Uganda before and after the 2021 elections. In the conclusion, we reflect on the implications of our analysis and method for research on Uganda; for theorising on the state, citizenship and affect; and as a means for addressing epistemic injustices.

Theorising citizenship moods through emotions and inclusion

As an expanding body of scholarship has highlighted, citizenship is not just a legal category, but rather, an experienced relationship between individuals and either the stateFootnote1 or other ‘structures of rule and belonging’.Footnote2 Particularly central for our analysis is the view that citizenship is both material and embodied. The notion of material citizenship draws on Ahimbisibwe'sFootnote3 analysis of the centrality of material assets for citizenship in Uganda, which emphasises that citizens not only hold legal status as members of a state, they also have stomachs to fill and school fees to pay. In this light, citizenship moods in Uganda are crucially shaped by the increasing inequality between Ugandans, and the way in which unprivileged citizens experience this inequality as exclusion from the state. With the notion of embodied citizenship,Footnote4 we highlight that citizenship is not just an abstract category: like individual and collective moods concerning the state, citizenship is also corporeal, and thereby experienced in and mediated through a range of bodily processes and sensory experiences.

Interest in the relationship between politics and what are variously termed emotions, feelings, sentiments, or affect has surged across academic disciplines in recent years, much of it under the rubric of the ‘affective turn’.Footnote5 This diverse literature converges around the desire to debunk the separation of emotion and reason. Most classical political thinkers disdained emotions as a threat to rationality, and as a hindrance to the development of ‘good’ citizenship and functioning ‘modern’ states.Footnote6 – a view vehemently questioned from numerous directions in recent decades. Social psychologists Peter Burke and Jan Stets have highlighted emotions as central for national affinity and bonding,Footnote7 while political psychologist George E. Marcus’s work portrays emotions as pivotal for citizenship: without enthusiasm, the citizenry would be passive, and without anxiety, it would not be sufficiently motivated to try to change anything.Footnote8 A similar argument is made by philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who sees emotions as essential for moral judgment and functioning political culture.Footnote9

Meanwhile, anthropologists have built on Ann Stoler’s notion of ‘affective states’Footnote10 to assess the role of emotion in sustaining the state as a source of authority, and to unpack the contextually specific affective charge of encounters between citizens and states. In an Introduction to a special issue on the theme, Laszczkowski and Reeves utilise Mitchell’s notion of the ‘state effect’,Footnote11 which they view as emerging ‘through the affective engagements of ordinary citizens and non-citizens in relation to state agents and state-like activities: their feelings, their emotions, their embodied responses as they navigate state bureaucracy or anticipate state violence’.Footnote12 In this vein, Montoya, for instance, interpreted the ‘passions on display in El Salvador’s 2009 elections [as] related to a renewed sense of possibility … for how Salvadorans imagined their relationship within the state’. Resonating with this, we employ the notion of moods to interpret Ugandan citizens’ (dis)engagements with the NRM state as they evolved prior to, through the time of and in the aftermath of the 2021 elections. We argue that ahead of the elections, a window of opportunity seemed to be opening for changed relationships between Ugandans and the state – only to be closed shortly thereafter.

But why do we speak of ‘moods’, and not, as is more common in the relevant literature, of ‘affect’ or ‘emotion’ – and why ‘citizenship’ rather than ‘political’ moods? First, ‘citizenship moods’ references the differentiation commonly made between ‘emotion’ as fleeting, and ‘mood’ as more persistent and stable, albeit not static.Footnote13 Relatedly, while ‘emotion’ is most typically understood as an individual experience, the concept of ‘mood’ refers more explicitly to something that can be both individually and collectively felt. Second, while ‘political mood’ can also refer to people’s views on political parties or topics of public debate, we use ‘citizenship mood’ to refer more specifically to the relationship between the state and its citizens. Third, although literature on affect provides us with key inspiration, we opt to speak of ‘moods’ rather than ‘affect’ because whereas the latter is largely used in certain academic circles, ‘mood’ is a word understood by most English-speakers, including our research interlocutors and the Ugandan public.

From the above starting points, we draw four general characteristics of citizenship moods that inform our analysis. 1) They are embodied and reflective, which means they emerge from the material realities of citizens’ lives, and rather than being mere pre-subjective ‘intensities’ as conceived in some strands of affect research,Footnote14 they are subject to and are moulded by both individual contemplation and collective debate. 2) At their heart are experiences of (non)belonging and (non)recognition by the state, since membership in a national community, even when endorsed by law, does not guarantee citizens equal access to recognition and rights.Footnote15 3) Citizenship moods emerge in particular historical contexts.Footnote16 For instance, the tensions around how rights and recognition are divided take very particular shape in Uganda, where the category of citizenship emerged out of the subjugation of multiple ethnic groups under a colonial state.Footnote17 4) They are embedded in social relations. As Brennan argues, it is because of their relationality that humans have an innate ability to sense the moods of others,Footnote18 an ability we put to use in our cartoon-powered analysis.

Cartoon-powered socio-political analysis

In this article, cartoons are not simply objects of analysis, rather, their production is both a method of analysis and a means for research communication. The analysis we present draws on participant observation and interviews, informal discussions, and media and social media materials we have accumulated over the course of our long-term research in Uganda. Jimmy Spire Ssentongo's insights draw particularly from his ethnographic research on pluralism in Western Uganda (Kibaale) and transitional justice in North-Eastern Uganda (Karamoja), and from his media engagement and lifelong embedded observation of everyday life in Kampala and rural Central Uganda.Footnote19 Henni Alava's analysis is grounded in ethnographic research on Christianity, politics and citizenship in Northern (Kitgum) and Central (Entebbe) Uganda, which has included countless interviews and conversations, some sustained for over a decade.Footnote20

Research for this article began in late 2019; just over a year before the 2021 elections; with a conversation about how hard it was to put a finger on the mood in Uganda at the time. Building on our earlier collaborative work,Footnote21 we decided to attempt to trace the mood in an analytical manner. To this end, we began to read through Ugandan media sites, social media feeds and our recent fieldwork notes, and to initiate discussions on the theme with interlocutors and acquaintances in Central and Northern Uganda, with the notion of ‘citizenship moods’ on our minds. After struggling to articulate our emerging arguments in a conference paper, it occurred to us to see whether ‘moods’ might be better captured in images – the way Spire (penname) does in his cartoons for the Observer, and through his Facebook page (Spire Cartoons) and Twitter account (@SpireJim).

Recently, the role of cartoonists as critical entertainers and public commentators in Africa has received growing scholarly attention.Footnote22As observed by Peter Limb in Taking African Cartoons Seriously, in their simplicity, cartoons can penetrate the mystique and hype around politics, and provide access to ‘everyday’ reactions to politics in a way that public opinion polls, for instance, cannot.Footnote23 Our use of cartoons in this article is somewhat different, however, in that we deploy their power not simply to communicate, but as an imprecise yet, we argue, powerful method of interpretive socio-political analysis.Footnote24 The article’s text and cartoons resulted from a back-and-forth process: brainstorming, writing and re-writing, Ssentongo giving graphic form to emerging arguments, and joint reflections on our own and our audiences’ responses to the images.

By intuitively tapping into art as a method for analytical inspiration, we followed what has in recent years become an increasingly well-trodden track. Political scientists have shown growing interest in cartoons as objects of analysis,Footnote25 and scholars like Joe Sacco have showcased the ability of graphic novels to convey social analysis and critique. Footnote26 Nick Sousanis’s ‘Unflattening’Footnote27 literally illustrates how academic thinking is limited by the privileging of text over image, and how drawing and images, used alongside text, can provide novel insights. We had from the get-go conceived of citizenship moods as profoundly embodied, and thereby also as experienced in our bodies as researchers; yet, when working only with words, we were limited in bringing bodies to the text. In a fascinating account of drawing, dancing, and writing, Jääskeläinen and Helin show how the use of drawings can make space for a researcher’s sensing body in a way that enables analysis of materials that otherwise get ‘flattened’ by the textual form.Footnote28 Reading this work after Ssentongo had drawn the first cartoons, we realised that due to their careful attunement to posture, the cartoons captured things that text struggled to convey. The cartooning process thus shaped and sharpened our observations and arguments.

As a final step to the method, and to avoid the risk of being trapped in echoes of our own sentiments, in November 2021 the cartoons were all posted together on the Facebook and Twitter accounts of Ssentongo, together with a text introducing our research and the question ‘do these images capture the moods around the 2021 elections?’ Ssentongo regularly posts their cartoons, both those published in the Observer and ones unpublished, onto these accounts, each of which is followed by over 120,000 people. The followers, some of whom write behind pseudonyms, include both those who share Ssentongo's political critiques and those who expressly support the incumbent regime. The ‘citizenship mood’ posts triggered close to 3,000 responses (overwhelmingly ‘likes’ and ‘laughs’), over 100 shares, and hundreds of comments. Most of the commentators said the cartoons ‘nailed it’, while some asked for certain aspects to be highlighted further. Overwhelmingly, requests for clarification concerned issues that we already discussed in the article text, yet some of the remarks also led us to nuance our arguments. Most notably, and as we will discuss further when analysing the mood of hope, the responses convinced Ssentongo that Alava's insistence on including hope as one of the citizenship moods was not as mistaken as Ssentongo's own growing frustration with the situation had at the time led him to conclude. The online responses to the cartoons cannot be considered ‘proof’ of our analysis, yet they do provide indication that the cartoons, and the moods we had identified, resonated beyond our personal impressions alone. From our epistemological starting point, and in light of our desire to push the boundaries of prevalent patterns of knowledge production, this was more than enough.

Linda Åhäll has noted that when political scientists turn to neuroscience – a research field portrayed as ‘rational’ – they often end up reconstituting the very dichotomy of reason and emotion that they seek to dismantle.Footnote29 Our turn to comics did the opposite: it was a conscious embrace of our intuition; a faculty we believe is often left out of accounts of research. As Pinker and Harvey write in their reflection on uncertainty in anthropologies of the affective state:

A gesture or a tone of voice might imply a particular disposition or mood – or perhaps not … [W]e argue that a focus on affect call[s] attention anew to the intrinsically relational, and by extension uncertain, quality of the ethnographic method. This defining attribute of ethnography continually vexes any attempt to finally disentangle what we think we know about others from the worlds we inhabit ourselves.Footnote30

The cartoons here contain both gentle and snide critiques of the incumbent regime, and seek to make clear our ethical and political commitment to justice and freedom from violence for all Ugandans. These commitments align with the artwork and public commentary of Ssentongo, and with our engaged scholarship: the cartoons simply make transparent what is more typically hidden behind a veil of academic jargon. Indeed, we make no claim to neutrality: through our lived experiences and the networks of commitment and care in which we are entwined in Uganda, we are emotionally engaged and implicated in the moods we describe.

Dynamics of citizenship and inequality in Uganda

We now turn to the dynamics that shape citizenship moods in contemporary Uganda. Building on Laszczkowski and Reeves’ contention that ‘the salience of particular moments of subjective feeling … stems from specific histories of subjectification and particular experiences of rule’,Footnote32 we suggest that citizenship moods are fundamentally connected with citizens’ perceptions of how well the state has succeeded in protecting and providing for them. These perceptions, in turn, are shaped by whether citizens feel that the way in which protection and provision is divided between groups, particularly one’s own group, is “fair”. Obviously, what constitutes fair is deeply contested. As Cheeseman et al. argue in their analysis of the moral economies of elections, two influential registers of morality – the civic and the patrimonial – shape politics in Uganda.Footnote33 Since these registers often pull in different directions, political debate and policy making is conditioned by the need to balance between them. This analysis helpfully challenges liberal ideas of ‘civic education’, nurtured by development donors,Footnote34 by acknowledging that what motivates citizens to engage in elections can be personal and group interest, rather than some abstract notion of ‘civic virtue’. What might be condemned in one moral register, such as prioritising development initiatives for one’s own ethnic group or ‘vote-buying’ (the civic), may appear entirely justifiable in the other (the patrimonial).Footnote35

To a degree, citizenship moods can be explained in light of the different moral registers Cheeseman et al. identify. However, in recognition of the complexity of identity politics,Footnote36 we suggest that the patrimonial register must be augmented by a broader range of divisions – class, age, gender, religion, alongside urban/rural divides – that coexist with and complicate ethnicity. To understand citizenship moods, it is vital to pay attention to these other axes of division, all of which profoundly influence how much access people have to protection and provision from the state, and consequently, their perceptions of it. A brief account of these divisions in Uganda is thus a prerequisite for our attempt to account for the citizenship moods they engender.

Uganda is a complex colonial creature.Footnote37 Under British rule, previously fluid boundaries between ethnic groups were solidified for administrative convenience, thus heightening ethnic consciousness and stereotypes.Footnote38 This led to the creation of two sets of citizenship identities, the national and the subnational,Footnote39 whereby ‘the concept of Uganda as a republic continued to make little sense to the citizenry’.Footnote40 Identity politics were further complicated by colonial missionary policy, which allowed two denominations to compete with each other countrywide, leaving Uganda at independence bifurcated between an Anglican state and a Catholic opposition. The complex crisscrossing of ethnic and religious divisions up until the present has invited manipulation and hindered coalition-building,Footnote41 and every regime since independence has been perceived to favour both the regional and religious identity of its president.

Yoweri Museveni’s NRM, which came to power in 1986, initially tried to address the problem by creating a broad-based system, purporting to be as inclusive as possible.Footnote42 While some commentators commended it for its attempts to depoliticise ethnicity,Footnote43 it soon took a back turn. In Rubongoya’s words, ‘regional/ethnic broad-basedness was not meant to be inclusive. Rather, the NRM sought to pander to different regions and ethnic groups in exchange for political support. Clientelism had gained regional and ethnic content.’Footnote44 Vokes’ observation that the ‘government’s spending on new infrastructure has been highly uneven across the country’Footnote45 is widely shared by Ugandans. The flammability of the topic was made clear in the run-up to the 2021 elections, when a group of Ugandan comedians known as Bi zonto and a prominent blogger, Basajja Mivule, were arrested for listing Ugandans from Western Uganda who hold prominent positions in the government. Although many Western Ugandans highlight that it is only a select few among them who reap the benefits of Museveni’s reign,Footnote46 media accounts as well as our own observations indicate an increase in resentment towards ‘Westerners’ overall. This is not simply about ethnic hatred; rather, at its core is the sense that particular groups are gleaning more than their fair share of national wealth.

Uganda was projected as one of the fastest growing economies in Africa in the late 1980s and 1990s, yet economic growth has been coupled with a growth in income inequality, which is patterned by intersecting age, gender, and rural/urban divides. In 2017, over half of the national income was in the hands of the richest 20% of the population,Footnote47 and despite the official grand utopia of development featured on billboards,Footnote48 many Ugandans have seen little improvement in the standards of public social service delivery, and have no access to quality education or healthcare..Footnote49 A staggering 53% of citizens are under 18, and a further 22% are aged 18–30s.Footnote50 Conservative estimatesFootnote51 place youth unemployment at 13%, and of those who are employed, over a third are underemployed.Footnote52 Poverty levels are higher in rural areasFootnote53, where over 80% of Ugandans live.Footnote54 The resultant youth migration to towns has created a notable new constituency: ‘ghetto youth'Footnote55 have no personal memory of tumultuous earlier eras, whereby the NRM’s narrative of ‘liberation’ carries little appeal among them.Footnote56 These dynamics produce mixed results for citizens’ access to protection and provision by the state. Some are increasingly discontent, while others strive to protect their positions or to position themselves in a way that might enable access to state resources. Increasingly, the NRM regime has adopted a combination of violence, legislative autocracy, and patronage;Footnote57 what TapscottFootnote58 refers to as ‘arbitrary governance’; to manage these tensions and maintain its hold on power.

Increased public dissent in particular has led the regime to tighten its grip on political expression. Prior to the 2021 elections, Covid-19 functioned as a handy reason to limit opposition rallies in attempt to curtail the growing support for pop-star turned politician, Robert Kyagulanyi (aka Bobi Wine) and his National Unity Platform (NUP) party. New forms of restrictions have also been imposed to control public debate on social media, including the Regulation of Interception of Communication Act (2010), which allows people’s private communications to be tapped. During the 2021 elections, the entire Internet was shut down for a full week starting two days before polling day, and, at the time of writing, Facebook remains banned.

Against the backdrop of the above dynamics, we turn now to trace how citizenship moods fluctuated during the run-up to and in the aftermath of the 2021 elections. As we will show, citizenship moods co-exist and change in complex ways both across time, and from one citizen to another: while some moods are fairly static, others fluctuate, sometimes with clear cyclicality. As in previous elections, the 2021 elections were preceded by a surge of hope for change, particularly among those who were tired of the regime. This was followed by increased violence, which led to more anger, fear, and ultimately a slump from hope to despondency. The analysis that follows is aided by the cartoons which Ssentongo drew to momentarily capture citizenship moods prevalent in Uganda during the given time period. They condense themes that were indicated to us through verbal and textual materials - informal chats, interviews, online debates, and the conversations we were having to iteratively make sense of our data.

Chronic fear and contentment

You young people are involved in what you don’t understand. If someone can even order you to keep in your houses without food and you stay there [during the COVID-19 lockdown], how do you start to think that you can remove him from power? (An elderly man in a casual chat with youths at a motorcycle garage, Nyanama town, 2019).

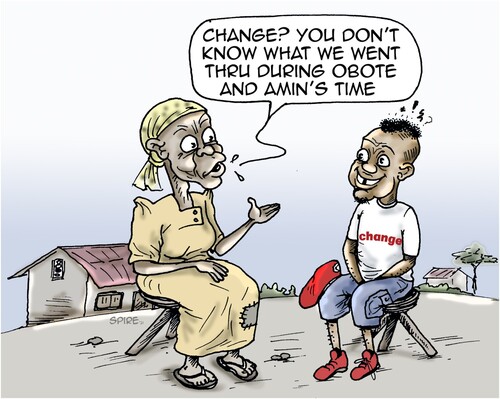

In the first cartoon (), an old lady dressed in faded NRM yellow counters a young “air-headed” man’s red-bereted demands for change by reminding him of the past. The image captures fear informed by memories of the ‘bad old days’ of ‘duka duka’ (run, run). Such fears are pervasive among Ugandans who personally experienced the brutality of Idi Amin and Milton Obote’s regimes. For this ageing and diminishing number of people, the narratives of ‘at least we can sleep now’ (‘twebaka ku tulo’ in Luganda), and ‘do not return us to the past’, remain strong. A similar narrative also has traction among certain groups of younger people, such as those in Acholi and Lango, who carry memories of the war between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the NRM governmentFootnote59; and in Karomoja, where many are simultaneously appreciative and apprehensive of the NRM government, following its high-handed disarmament of cattle rustlers in the recent years.Footnote60

Speaking of the 2021 elections in late 2019, a woman born in the 1970s in northern Uganda but living in Entebbe told us:

I always just vote for the President. I don’t see him as having done very much for me. But I vote for him anyway, so as to not give myself trouble. You know, the youth are really many these days, and they don’t fear. But the ones who have grown in Kampala, they have no idea. Growing up from the North, there has [sic] been too many guns in my life … [t]he memories are very alive in my mind. (Fieldwork notes, 2019)

While growing numbers of Ugandans are unhappy with Museveni’s government, others are contented enough with its performance to support it (). Many are satisfied because their expectations of the state are very low, so that even if they receive very little in exchange for the taxes they pay, they are happy enough that at least there is some symbolic or material improvement. A health centre built in the area, a tarmacked road, or the fact that working with the government increases the likelihood of such things happening, have all been cited to us over the years as some of the reasons for voting NRM. ‘No government is going to put money or food in your hands’, a lady from rural Central Uganda said. Such sentiments are captured in the image of young parents walking from a hospital with their newborn, and can be seen to reflect Cheeseman et al’s analysis on elections: many are content because they consider what the government does for them a favour, rather than as their due as citizens.

Many of those who support the regime are also motivated by short-term personal interest, either because the state provides them with patronage, or merely allows them to prosper through their own enterprise. One medical student who decided not to vote at all in 2021 rather than vote against the regime for fear of chaos told us, ‘However much we hate the guy, however useless this government is, it has been proven that it is still possible to thrive under him.’ Combining fear, contentment and a certain level of cynicism, the statement reflects how deeply moods are intertwined and why analysing the rise in different types of inequalities, whereby some Ugandans can ‘thrive’ while others cannot, is crucial for understanding both cynicism and anger among the electorate.

Cynicism and anger

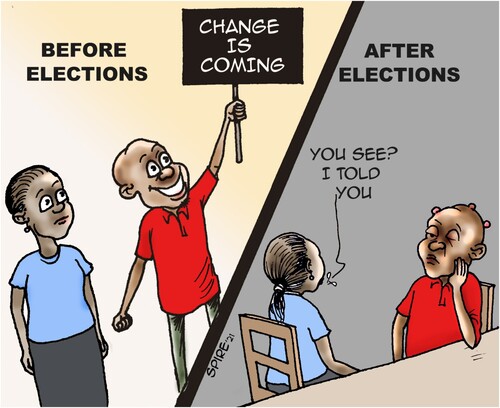

The prevalence of what we call cynical citizenship moods in Uganda is grounded in people’s understanding of the presidentialist and patrimonial nature of the Ugandan state, and in their subsequent choice to play the system rather than be crushed by it. Those who profit from state patronage and the suffering of others could be described as sinisterly cynical. Often, however, cynicism is characterised rather by a banal everydayness, and it is this that is captured by the cartoon below ().

In our reading, a cynical mood refers not only to people’s descriptions of having lost hope. It is also evident in the ways in which they discuss the political system and their methods of manoeuvring within it – including their choice to vote. This is well captured in a story told to us by an interlocutor:

A friend of mine got one million shillings for ticking ballot papers for Museveni in the previous elections. When she came to me a year after the election to ask for money for school fees, I told her forget it. She should have thought about this when she was asked to tick. Instead of the million, she should have demanded a post at the revenue authority or something, so that at least [her] efforts would have made for something sustainable.

Two bloggers, ‘Full Figure’ and ‘Bajjo’, who had been coaxed from People Power into the NRM, turned their coats again after the elections, saying the NRM abandoned them on tribal grounds in doling out rewards. Musician Hassan Ndugga crossed to Museveni’s side in 2019 and quipped that ‘Politics is gambling’ (Butereevu, BBS Terefayina, January 14, 2020); when he failed to get what he was promised, he released a song hitting out at the president for overstaying his time in power and for ignoring the poor. And right before the 2021 elections, Ronald Mayinja, who had been one of the regime’s musical critics for years, was co-opted to sing Museveni’s lead campaign song titled ‘The vote is for Mzee [Museveni]’.

The idea that one’s vote is for sale, and that support for leaders is contingent on their distribution of benefactions to citizens, resonates with long-standing patrimonial structures of governance. Schneidermann has argued that the ambiguous relationships between Ugandan musicians and politicians reveals a shift in political culture, wherein musicians perform complex brokerage roles amid the mixed expectations of their fans, their need for security and income, and those with political power.Footnote64 Yet from the ordinary citizens’ perspective, such manoeuvring often comes across as simply cynical. Indeed, while patronage may resound with traditional norms,Footnote65 its particular form and extent appear to be increasingly diverging from the ‘traditional’ morality of patronage, and eating away at citizens’ trust that leaders have the general populations’ best interest at heart. Growing inequality compounds this mistrust. Indeed, recognising the growth in age, ethnic, and class-based inequalities is absolutely vital for understanding why we group cynicism and anger together under the same subtitle. Thriving under Museveni’s regime is mostly possible for those who have the means to study for a profession that assures them a livelihood or who have the connections required to find work in sectors where jobs are few and far between. Thus the cynical calculations of the lucky few, be they politicians, musicians, or silent supporters of the regime that is feeding them, tend to provoke anger in others.

The cartoon on anger captures real actions of a man who paraded an effigy of President Museveni down the middle of a road in Kampala, flogging it while castigating Museveni through a megaphone . At the time of writing this article, he remains locked up. As the regime has continued to hang on to power, anger has become increasingly prevalent among Ugandan citizens, manifesting in what are often reckless expressions. Responding to a question about what she sees ahead in the 2021 elections, a well-educated unemployed woman almost spat with annoyance:

I wish he [Museveni] would just drop dead and leave us all in peace. What has he ever given us, except these Chinese roads? Does he think we’re STUPID? Enough is enough. It’s no longer the old who are angry, it’s the youth. We are many. And we don’t have jobs. (Interview, late 2019)

Since the 2016 elections, the key channel through which feelings of anger among Ugandan citizens have been funnelled has been the People Power Movement, and later the NUP. Throughout 2019, 2020, and 2021, Wine’s attempts to organise concerts/rallies have been repressed, which has incited Wine’s followers even further. With most of the physical public space being violently patrolled by government forces, much of this anger is vented in the relatively safer social media space through memes, music, insults and cartoons. Prominent among the angry activists has been Stella Nyanzi, the feminist scholar and activist aligned with the opposition party, Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), and the People Power movement (not NUP),Footnote67 who was arrested in 2017 and charged with cyber harassment for calling the president a ‘pair of buttocks’, and eventually convicted for this and other related offences to 18 months in jail.Footnote68 The cartoons of Ssentongo, and others like Ogon, as well as Nyanzi’s poems, can be seen as an expression of anger paired with hope, producing action. Yet as we now turn to describe, hope is frightfully easy to shut down. As an interlocutor who was completely drawn up in PP mobilisation prior to the elections put it once the elections were over,‘[when] there’s nothing you can do about it, you end up sitting back and just dying with your frustration, because there’s no outlet, no release.’

Hope, acute fear, despondence

Prior to the 2021 elections, hopeful citizenship moods increased in many parts of Uganda. Not only was this apparent in our research interactions and observations, an Afrobarometer survey also indicated that 58% of Ugandans believed that elections work ‘well’ or ‘very well’ as a mechanism for holding non-performing leaders accountable, a significant increase from 47% in 2015.Footnote69 After four failed attempts by Kizza Besigye, there was a new player on the scene, who seemed to be catching the imagination of both Ugandan and international audiences. Some years ahead of the 2021 elections, Bobi Wine filled Ugandan radio space with hopeful lyrics: ‘when we come together as one we can change our destinyFootnote70; ‘when the struggle is over we shall wear the victors’ crown … we shall walk with swag in a new Uganda’.Footnote71 Many young people, especially in Southern and Central Uganda, saw hope in Bobi, and his popularity was strikingly high. Urban youths, and some older people who had not been particularly excited about politics before, looked forward to voting, and hopes for change () were further raised by observations that the state was responding to his popularity in a panicky manner.

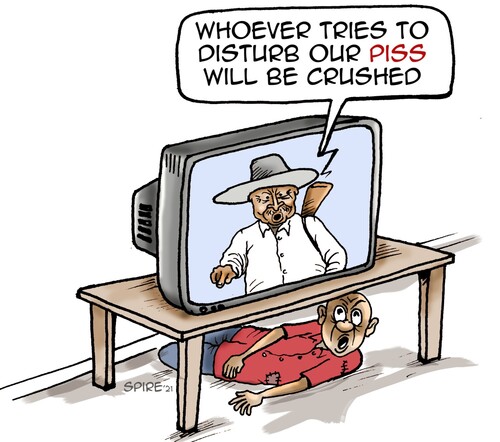

It was in this setting, we claim, that the NRM government began purposefully cultivating a mood of acute fear, compounded with that of cynicism. While Museveni has been said to be ‘a master in manipulating collective political affect’Footnote72, he is equally a master of violence when manipulation of affect fails. Intimidation, violence, and bribery have been significant factors in recent elections:Footnote73 army trucks and teargas tanks are strategically parked in conspicuous positions such as roundabouts, military helicopters hover over Kampala, and long lines of soldiers patrol the streets. In the run-up to the 2021 elections, the deployment of security personnel and military artillery was greater than during any previous elections under Museveni. Citing COVID-19 as a convenient cover, security forces fired teargas to disband opposition rallies even in small rural towns. Opposition supporters risked being crushed if they took to the streets, and as the election neared, many were roughed up or kidnapped by unidentified government agents.

The second cartoon on the fearful citizenship mood conveys the entanglement of fear related to the past and fear in the present (). While the president insists that the NRM is the guarantor of peace and that he will crush those who disturb it, the opposition-leaning, red-shirted man cowering under his table encapsulates the knowledge that it is the government’s pissing on its citizens that must not be disturbed. The government’s redeployment of the peace narrative during the 2021 elections played the double strings of chronic and acute fear to perfection. In this narrative, the opposition and its young (particularly male) supporters are framed as villains threatening to resurrect the monster of Uganda’s past violence. Through this narrative, the regime both distances itself from the violence, and plays with its threat; the president and some NRM cadres (such as Gen. Elly Tumwine, Kahinda Otafiire, Shaban Bantariza, etc.) have stated that a mere ballot paper cannot remove them from office, subtly implying that the only way to replace someone who came to power through the gun is by the gun. Importantly, the narrative also plays with the generational divide, constructing a youth phobia among elders.

In November 2020, over 50 opposition supporters were killed when government forces crushed protests in Kampala following Bobi Wine’s arrest at a campaign rally.Footnote74 In December 2020, Wine’s entire campaign team was rounded up and arrested on the campaign trail in the Ssese islands: several of them remain imprisoned while waiting to be court-martialled for ‘possession of arms’. Some weeks after the election, journalists covering Wine's submission of a petition to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Kampala were beaten with batons by security operatives.Footnote75 Altogether, NUP has reported over 400 of their supporters missing following clandestine military operations, and others found dead. All this served to feed a mood of fear, adding to a repository of the same mood’s historic precedents among Ugandans, and pre-empting ideas of protest or resisting the state. As hope for change slowly faded, despondence spread to take its place.

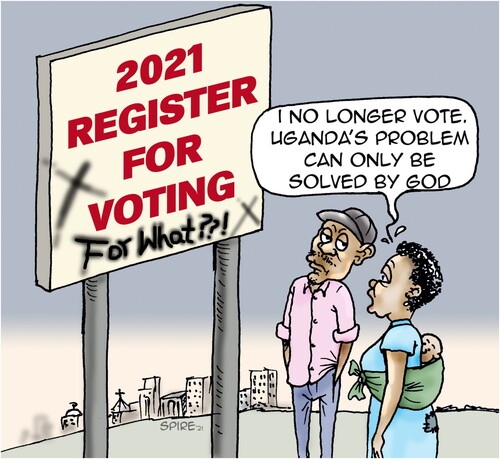

The above cartoon captures key aspects of the despondency prevalent among Ugandans (). A young woman with roots in the West Nile but living in Entebbe explained her lack of interest in politics:

In this Uganda, the president has been there for 30 years, so even if you vote, nothing changes … So I have no interest in voting. I just welcome any leader who comes. The Bobi Wine thing, it’s not good he was tortured, but there’s nothing you can do, so I don’t support him any more than I do any other party, and my friends are all the same … So you just pray, and you cope with things the way things are. (Interview, Entebbe, October 2019)

Despondence also connects with fear. For many in northern Uganda, a legacy of state violence has led to a ‘subdued citizenship’ wherein voting for the NRM is conceived as a pragmatic alternative to activism and even ‘a necessary life-preserving measure’.Footnote77 Such calculations were also evident in the statement made to us in late 2019 by a man from northern Uganda:

The one you send to Kampala [your MP], maybe before he used to help your village, but today, that is no longer there. So people have lost their hope in voting. As long as no one comes to beat you up at home, it is okay … So why can’t I just remain at home with my family, rather than supporting any kind of politics, which will just destroy my life? Up to now people are in prison for doing that … So for 2021, there is no any difference for Uganda. Not then, not any time as long as Museveni is alive. Even those who are for Bobi Wine, they know this … Museveni is untouchable. His leadership is military. Even if you see what is wrong, you should just be quiet. (Interview, Entebbe, November 2019)

The lightening of the mood to one of hope in 2020 was thus only momentary. With state violence heightened, elections marred by gross irregularities, the court election petition aborted, and all outlets for protest blocked by the state, post-election debates petered out in confusion and in-fighting among the opposition: despondence was resurgent. The NUP’s campaign slogan, ‘We are removing a dictator’, gradually changed to, ‘Nothing lasts forever.’ The dwindling of hope did not come as a surprise to those who had not been caught up in it, especially after the experience of Besigye’s violent deflation in previous elections. As captured by Ssentongo’s combined cartoon on the two moods, sceptics considered those who still had hope naïve. The pattern of elation and deflation was also seen around the 2011 and 2016 elections. Yet in 2021, Ugandans who still had hope of change seem to have plunged deeper into despondency than in previous election cycles. When even the slightest spark of protest was snuffed out, so was much of the mood of hope. Agitation shifted from calls for ‘change’ to the release of political prisoners.

A year after the violent crushing of opposition protests, a Facebook user commented on our cartoons: ‘My heart still bleeds and I shudder at what happened in November. It took me by surprise. I never expected it.’ A bleeding heart provides infertile ground for hope, and these types of sentiments served to confirm much of the despondence we felt as researchers following Ugandan politics. Yet what took us by surprise was the insistence of a handful of commentators that despite everything, hope remains. One of them wrote:

[Y]ou haven't represented the spirit of those of us [who] are resilient, still hopeful, and absolutely refuse to give up. The hopefuls among us, us that continue to encourage and cheer on our opposition leaders and help them up when … they have been beaten down … Represent us and the picture will be complete.

Conclusion

To conclude, we wish to elaborate on three interconnected points. The first of these concerns patterns of Ugandan politics under Museveni. Bobi Wine generated a mood of hope among Ugandans, and many previously politically passive citizens were invigorated. As one of our interlocutors put it in 2020: ‘In almost all the Whatsapp groups, politics prevails; in the bar, in birthday parties; politics has become part of our daily bread, when before, it was left to politicians.’ Yet the mood of hope took a huge hit after the election: while the die-hard few remained hopeful, many others slunk to despondence. This pattern repeated what has been seen in Uganda’s earlier elections, yet we argue that in 2021 the fall was steeper than before. Both the NRM regime’s scaling up of violence and clientelism in response to rising hope and anger among Ugandans, and the speed with which these measures led to a flattening of hope for change, and cat-fighting between opposition groups, point to just how unlikely it seems for power to be transferred in any future elections in which Museveni is a candidate.

The second point echoes previous research on affective statesFootnote78 and emotions and politicsFootnote79 to highlight the centrality of moods in state-citizen relations. As the Ugandan case shows, citizenship moods are both persistent and malleable. Similar to the case described by Montoya,Footnote80 Ugandans approaching the 2021 elections envisaged the possibility that a regime transition might allow formerly excluded citizens to gain access to state power and resources. Yet that hope was quashed when elections were hijacked by the regime. Complementing previous scholarship on the complexity of citizenship in postcolonial Africa,Footnote81 we have shown how citizenship is both moulded by and engenders intersecting and fluctuating moods. The analysis we present also highlights the need to understand shifts in these moods as profoundly related to the growing inequalities brought about by neoliberalisation.Footnote82

Our final point concerns both methodology and, relatedly, the ethics and politics of research. Experimenting with what evolved into a method of cartoon-powered sociopolitical analysis provided us with vital insights into citizenship, politics, and inequality in Uganda. Our experience suggests that cartoon-powered analysis, and other arts-based methods, can provide a powerful way of gauging citizens’ moods concerning politics, which can be particularly useful in situations where the use of survey methods, for instance, is logistically or financially unfeasible. Furthermore, the cartoons created through the research process provided us with the means of communicating our findings to a much broader audience, including our research interlocutors, than is the case for most academic research. By increasing social relevance, cartoon-powered analysis can help address some of the underlying epistemic injustices that plague research on Africa.Footnote83 Moreover, by making explicit the relationality of moods, and the degree to which all scholarly analysis is based on intuition and ‘crafted out of fields of doubt and indeterminacy’,Footnote84 such methods can contribute to breaking down the artificial barrier between the academic as ‘knower’ and the citizen as ‘known’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Kabeer, “The Search for Inclusive Citizenship.”

2 Koning, Jaffe, and Koster, “Citizenship Agendas in and beyond” 121.

3 Ahimbisibwe, “Exploring Obutyamye as Material Citizenship in Busoga Subregion, Uganda.”

4 Alava, “The Everyday and Spectacle.”

5 Clough and Halley, The Affective Turn.

6 Hordern, Political Affections.

7 Burke, and Stets, Identity Theory.

8 Marcus, The Sentimental Citizen, 111.

9 Nussbaum, “Cultivating Humanity”; Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought.

10 Stoler, “Affective States.”

11 Mitchell, “‘Society Economy and the State Effect.’”

12 Laszczkowski and Reeves, “Introduction,” 7.

13 Ketai, “Affect, Mood, Emotion, and Feeling.”; Burke and Stets, Identity Theory.

14 see Steinmüller, “‘Father Mao’ and the Country-Family” for a critique.

15 Holston, Insurgent Citizenship; Ng’weno, “Beyond Citizenship as We.”

16 Laszczkowski and Reeves, “Introduction,” 7.

17 Ng’weno and Aloo, “Irony of Citizenship,” 147.

18 Brennan, The Transmission of Affect.

19 Ssentongo, “Spaces for Pluralism in ‘Ethnically Sensitive”; Ssentongo, Quarantined: My Ordeal in Uganda’s; Ssentongo and Okok, “Rethinking Anti-Corruption Strategies.”

20 Alava, Christianity, Politics and the Afterlives of War; Alava, “Tiny Citizenship, Twisted Politics.”

21 Alava and Ssentongo, “Religious (de)Politicization.”

22 Dodds, ”Popular Geopolitics and Cartoons”; Hammett, “Political Cartoons, Post-Colonialism and Critical African Studies”; Limb and Tejumola, Taking African Cartoons Seriously.

23 Duus, ‘Presidential Address: Weapons’.

24 for a similar methodology, see Böhrer, Döbler, and Tarkkala, “Facemasks, Material and Metaphors” 7.

25 Sani et al., “Political Cartoons in the First Decade.”

26 Sacco, Palestine; Footnotes in Gaza; Paying the Land.

27 Sousanis, Unflattening.

28 Jääskeläinen and Helin, “Writing Embodied Generosity.”

29 Åhäll, “Affect as Methodology,” 2.

30 Pinker and Harvey, “Negotiating Uncertainty,” 18.

31 Stoler, “Affective States.”

32 Laszczkowski and Reeves, “Introduction,” 8.

33 Cheeseman, Lynch and Willis, The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa.

34 For a critique grounded in philosophical pragmatism and East African contexts, see Holma and Kontinen Practices of Citizenship in East Africa.

35 Cheeseman, Lynch, and Willis, The Moral Economy.

36 Keller, Identity, Citizenship, and Political

37 see Mafeje, “The Ideology of ‘Tribalism’”; Mamdani, Citizen and Subject

38 Mamdani, Citizen and Subject; Ssentongo, “Spaces for Pluralism.”

39 Keller, Identity, Citizenship, and Political Conflict in Africa.

40 Kabananukye, “Ethnic Diversity: Implications to Development,” 262.

41 Alava and Ssentongo, “Religious (de)Politicization.”

42 Rubongoya, Regime Hegemony in Museveni’s Uganda.

43 For an overview, see Tripp, Museveni’s Uganda.

44 Rubongoya, Regime Hegemony, 15.

45 Vokes, “Signs of Development”, 315.

46 Taylor and Matsiko, “How Uganda’s Election Re-Exposed.”

47 Oxfam International, “Who Is Growing?”

48 Vokes, “Signs of Development.”

49 Asiimwe, “The Impact of Neoliberal Reforms.”

50 UBOS, “National Labour Force Survey 2016/2017.”

51 UBOS, “State of Uganda Population Report 2018.”

52 UNFPA, “Worlds Apart in Uganda.”

53 The World Bank, “Poverty Maps of Uganda.”

54 World Population Review, “Uganda Population 2020.”

55 Baral, “Bad Guys, Good Life.”

56 Reuss and Titeca, “When Revolutionaries Grow Old.”

57 Perrot, Makara, and Lafargue, Elections in a Hybrid Regime; Tripp, Museveni’s Uganda.

58 Tapscott, Arbitrary States.

59 Alava, “‘Acholi Youth Are Lost’?”

60 Närman, “Karamoja”; Ssentongo et al., “Post-Disarmament Community Conflict Resolution.”

61 Daily Monitor, “Bantariza Gun Remarks Trigger Public Uproar,” 3 December 2019, sec. Nation. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/bantariza-gun-remarks-trigger-public-uproar-1862672?view = htmlamp.

62 Wilkins, “Capture the Flag.”

63 Friesinger, “Patronage, Repression, and Co-Optation.”

64 Schneidermann, “Ugandan Music Stars.”

65 Cheeseman, Lynch, and Willis, The Moral Economy of Elections.

66 Scott, Weapons of the Weak.

67 Nyanzi, No Roses from My Mouth.

68 see “Naked Bodies and Collective Action.”

69 Kakumba 2020

70 Wine, Uganda Zukuka.

71 Wine, Tuliyambala Engule.

72 Vokes, “Signs of Development”, 306.

73 Titeca and Onyango, “The Carrot and the Stick”; Vokes and Wilkins, “Party, Patronage and Coercion.”

74 Andrew Bagala, “Death Toll from Riots Rises to 50.” Daily Monitor, 24 November 2020. https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/special-reports/death-toll-from-riots-rises-to-50--3208320.

75 Nyeko, “Uganda’s Beaten Journalists Deserve Justice.”

76 Alava and Ssentongo, “Religious (de)Politicization.”

77 Alava, “The Everyday and Spectacle,” 102.

78 Stoler, “Affective States”; Laszczkowski and Reeves, “Introduction.”

79 Nussbaum, Upheavals of Thought; Marcus, The Sentimental Citizen.

80 Montoya, “The Turn of the Offended.”

81 Ng’weno and Aloo, “Irony of Citizenship,” 147.

82 Wiegratz et.al., “Introduction: Interpreting Change.”

83 Ssentongo, “‘Which Journal Is That?”

84 Pinker and Harvey, “Negotiating Uncertainty,” 18.

Bibliography

- Abonga, Francis, Raphael Kerali, Holly Porter, and Rebecca Tapscott. “Naked Bodies and Collective Action: Repertoires of Protest in Uganda’s Militarised, Authoritarian Regime.” Civil Wars 22, no. 2–3 (2019): 1–26. doi:10.1080/13698249.2020.1680018.

- Abu-Lughod, Lila, and Catherine A. Lutz. “Introduction: Emotion, Discourse, and the Politics of Everyday Life.” In Language and the Politics of Emotion, edited by Catherine A. Lutz, and Lila Abu-Lughod, 1–23. Cambridge, New York: Paris: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Åhäll, Linda. “Affect as Methodology: Feminism and the Politics of Emotion.” International Political Sociology 12, no. 1 (2018): 36–52. doi:10.1093/ips/olx024.

- Ahimbisibwe, Karembe. “Exploring Obutyamye as Material Citizenship in Busoga Subregion, Uganda.” Nordic Journal of African Studies 31, no. 4 (2022): 329–349. doi:10.53228/njas.v31i4.962.

- Alava, Henni. “‘Acholi Youth Are Lost’? Young, Christian and (a)Political in Uganda.” In What Politics? Youth and Political Engagement in Africa, edited by Elina Oinas, Henri Onodera, and Leena Suurpää, 158–178. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

- Alava, Henni. Christianity, Politics and the Afterlives of War in Uganda. “There Is Confusion.” New Directions in the Anthropology of Christianity. Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

- Alava, Henni. “The Everyday and Spectacle of Subdued Citizenship in Northern Uganda.” In Practices of Citizenship in East Africa. Perspectives from Philosophical Pragmatism, edited by Katariina Holma, and Tiina Kontinen, 90–104. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Alava, Henni. “Tiny Citizenship, Twisted Politics, and Christian Love in a Ugandan Church Choir.” Nordic Journal of African Studies 31, no. 4 (2022): 374–401. doi:10.53228/njas.v31i4.964.

- Alava, Henni, and Jimmy Spire Ssentongo. “Religious (de)Politicization in Uganda’s 2016 Elections.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 4 (2016): 677–692. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1270043.

- Asiimwe, Godfrey B. “The Impact of Neoliberal Reforms on Uganda’s Socio-Economic Landscape.” Uganda: The Dynamics of Neoliberal Transformation. ZED, London, 2018, 145–77.

- Baral, Anna. “Bad Guys, Good Life: An Ethnography of Morality and Change in Kisekka Market (Kampala, Uganda),” PhD diss., Uppsala University. 2018. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn = urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-343984.

- Böhrer, Annerose, Marie-Kristin Döbler, and Heta Tarkkala. “Facemasks, Material and Metaphors: An Analysis of Socio-Material Dynamics of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Sociological Review (March 24, 2023): 00380261231161970. doi:10.1177/00380261231161970.

- Brennan, Teresa. The Transmission of Affect. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Cheeseman, Nic, Gabrielle Lynch, and Justin Willis. The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa: Democracy, Voting and Virtue. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. doi:10.1017/9781108265126.

- Clough, Ticineto, and Jean Halley. The Affective Turn. Theorizing the Social. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007. https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-affective-turn.

- Friesinger, Julian. “Patronage, Repression, and Co-Optation: Bobi Wine and the Political Economy of Activist Musicians in Uganda.” Africa Spectrum 56, no. 2 (2021): 127–150. doi:10.1177/00020397211025986.

- Holma, Katariina, and Tiina Kontinen. eds. Practices of Citizenship in East Africa: Perspectives from Philosophical Pragmatism. 1st ed. New York: Routledge, 2019. doi:10.4324/9780429279171.

- Holston, James. Insurgent Citizenship. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691142906/insurgent-citizenship.

- Hordern, Joshua. Political Affections: Civic Participation and Moral Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Jääskeläinen, Pauliina, and Jenny Helin. “Writing Embodied Generosity.” Gender, Work & Organization 28, no. 4 (2021): 1398–1412. doi:10.1111/gwao.12650.

- Kabananukye, K. I. B. “Ethnic Diversity: Implications to Development.” In Confronting Twenty-First Century Challenges VOLUME ONE, edited by Ruth Mukama, and Murindwa-Rutanga, 257–279. Kampala: Faculty of Social Sciences, Makerere University, 2004.

- Kabeer, Naila. “The Search for Inclusive Citizenship: Meanings and Expressions in an Inter-Connected World.” In Inclusive Citizenship: Meanings and Expressions, edited by Naila Kabeer, 1–27. London: Zed Books, 2005.

- Keller, Edmond J. Identity, Citizenship, and Political Conflict in Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014.

- Ketai, Richard. “Affect, Mood, Emotion, and Feeling: Semantic Considerations.” American Journal of Psychiatry 132, no. 11 (1975): 1215–1217. doi:10.1176/ajp.132.11.1215.

- Koning, Anouk de, Rivke Jaffe, and Martijn Koster. “Citizenship Agendas in and Beyond the Nation-State: (en)Countering Framings of the Good Citizen.” Citizenship Studies 19, no. 2 (2015): 121–127. doi:10.1080/13621025.2015.1005940.

- Laszczkowski, Mateusz, and Madeleine Reeves. “Introduction: Affective States—Entanglements, Suspensions, Suspicions.” Social Analysis 59, no. 4 (2015): 1–14. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590401.

- Mafeje, Archie. “The Ideology of ‘Tribalism.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 9, no. 2 (1971): 253–261. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00024927.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. Citizen and Subject : Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Fountain Edition 2004. Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers, 1996.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. Define and Rule: Native as Political Identity. The W.E.B. Du Bois Lectures. Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Marcus, George E. The Sentimental Citizen: Emotion in Democratic Politics. 1 edition. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2002.

- Mitchell, Timothy. “Society Economy and the State Effect.” In The Anthropology of the State: A Reader, edited by Aradhana Sharma, and Akhil Gupta, 76–97. Blackwell readers in anthropology. Malden, Mass: Blackwell, 2006.

- Montoya, Ainhoa. “The Turn of the Offended.” Social Analysis 59, no. 4 (2015): 101–118. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590407.

- Närman, Anders. “Karamoja: Is Peace Possible?” Review of African Political Economy 30, no. 95 (2003): 129–169.

- Ng’weno, Bettina. “Beyond Citizenship as We Know It: Race and Ethnicity in Afro-Colombian Struggles for Citizenship Equality.” In Comparative Perspectives on Afro-Latin America, edited by Kwame Dixon, and John Burdick, 156–175. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012. doi:10.5744/florida/9780813037561.003.0008.

- Ng’weno, Bettina, and L. Obura Aloo. “Irony of Citizenship: Descent, National Belonging, and Constitutions in the Postcolonial African State.” Law & Society Review 53, no. 1 (2019): 141–172. doi:10.1111/lasr.12395.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. “Cultivating Humanity.” Liberal Education 84, no. 2 (1998): 38.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Nyanzi, Stella. No Roses from My Mouth: Poems from Prison. Kampala: Ubuntu Reading Group, 2020.

- Nyeko, Oryem. “Uganda’s Beaten Journalists Deserve Justice.” Human Rights Watch, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/22/ugandas-beaten-journalists-deserve-justice.

- Oxfam International. “Who Is Growing? Ending Inequality in Uganda.” Kampala, Uganda, 2017. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/who-growing-ending-inequality-uganda.

- Perrot, Sandrine, Sabiti Makara, and Jérôme Lafargue, eds. Elections in a Hybrid Regime. Revisiting the 2011 Ugandan Polls. Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 2014.

- Pinker, Annabel, and Penny Harvey. “Negotiating Uncertainty.” Social Analysis 59, no. 4 (2015): 15–31. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590402.

- Reuss, Anna, and Kristof Titeca. “When Revolutionaries Grow Old: The Museveni Babies and the Slow Death of the Liberation.” Third World Quarterly 0, no. 0 (2017): 1–20. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1350101.

- Rubongoya, Joshua B. Regime Hegemony in Museveni’s Uganda - Pax Musevenica. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Sacco, Joe. Footnotes in Gaza. Illustrated edition. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010.

- Sacco, Joe. Palestine. 1st edition. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics, 2001.

- Sacco, Joe. Paying the Land. Illustrated edition. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020.

- Sani, Iro, Mardziah Hayati Abdullah, Afida Mohamad Ali, and Faiz S Abdullah. “Political Cartoons in the First Decade of the Millennium.” Social Sciences & Humanities 22, no. 1 (2014): 73–83.

- Schneidermann, Nanna. “Ugandan Music Stars Between Political Agency, Patronage, and Market Relations: Cultural Brokerage in Times of Elections.” Nordic Journal of African Studies 29, no. 4 (2020): 1–19.

- Scott, James C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985.

- Sousanis, Nick. Unflattening. Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Ssentongo, Jimmy Spire. Quarantined: My Ordeal in Uganda’s Covid-19 Isolation Centers. Kampala, Uganda: Ubuntu Reading Group, 2021.

- Ssentongo, Jimmy Spire. “Spaces for Pluralism in ‘Ethnically Sensitive’ Communities in Uganda – The Case of Kibaale District.” PhD diss., University of Humanistic Studies, 2015.

- Ssentongo, Jimmy Spire. “‘Which Journal Is That?’ Politics of Academic Promotion in Uganda and the Predicament of African Publication Outlets.” Critical African Studies 12, no. 3 (2020): 283–301. doi:10.1080/21681392.2020.1788400.

- Ssentongo, Jimmy Spire, M. Aciru, T. Ogwang, and S. Parmentier. “Post-Disarmament Community Conflict Resolution and Justice Mechanisms in Karamoja Region of Uganda.” East African Journal of Peace and Human Rights 27, no. 3 (2021): 274–301.

- Ssentongo, Jimmy Spire, and Samuel Okok. “Rethinking Anti-Corruption Strategies in Uganda: An Ethical Reflection.” African Journal of Governance & Development 9, no. 1 (2020): 66–88.

- Steinmüller, Hans. “‘Father Mao’ and the Country-Family.” Social Analysis 59, no. 4 (2015): 83–100. doi:10.3167/sa.2015.590406.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. “Affective States.” In A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics, edited by D. Nugent and J Vincent, 4–20. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2008. doi:10.1002/9780470693681.ch1.

- Tapscott, Rebecca. Arbitrary States: Social Control and Modern Authoritarianism in Museveni’s Uganda. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Taylor, Liam, and Haggai Matsiko. “How Uganda’s Election Re-Exposed Regional Faultlines.” African Argumens, 2021. https://africanarguments.org/2021/03/how-ugandas-election-re-exposed-regional-faultlines/.

- The World Bank. “Poverty Maps of Uganda.” Technical Report. The World Bank, 2018. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/456801530034180435/Poverty-Maps-of-Uganda.

- Titeca, Kristof, and Paul Onyango. “The Carrot and the Stick: The Unlevel Playing Field in Uganda’s 2011 Elections.” In L’Afrique Des Grands Lacs : Annuaire 2010-2011., edited by F Reyntjens, S Vandeginste, and M Verpoorten, 111–130. Paris: Harmattan, 2012.

- Tripp, Aili Mari. Museveni’s Uganda : Paradoxes of Power in a Hybrid Regime. Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2010.

- UBOS. National Labour Force Survey 2016/2017. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2018.

- UNFPA. “Worlds Apart in Uganda: Inequalities in Women’s Health, Education and Economic Empowerment.” Population Matters. United Nations Population Fund, 2017. https://uganda.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Issue%20Brief%205%20-%20special%20edition.%20inequalities.final_.pdf.

- Vokes, Richard. “Signs of Development: Photographic Futurism and the Politics of Affect in Uganda.” Africa 89, no. 2 (2019): 303–322. doi:10.1017/S0001972019000081.

- Vokes, Richard, and Sam Wilkins. “Party, Patronage and Coercion in the NRM’S 2016 Re-Election in Uganda: Imposed or Embedded?” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 4 (2016): 581–600. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1279853.

- Wiegratz, Jörg, Giuliano Martiniello, and Elisa Greco. “Introduction: Interpreting Change in Neoliberal Uganda.” In Uganda: The Dynamics of Neoliberal Transformation, edited by J. Wiegratz, M. Giuliano, and E. Greco, 1–40. New York: Zed Books, 2018.

- Wilkins, Sam. “Capture the Flag: Local Factionalism as Electoral Mobilization in Dominant Party Uganda.” Democratization 26, no. 8 (2019): 1493–1512. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1658746.

- Wine, Bobi. Tuliyambala Engule. Featuring Nubian Li, King Saha, Irene Namatovu, Dr. Hilderman, P.R. Wilson Bugembe and Rene Ntale. Produced by Dan Magic. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = jJcqew3dQ9 g.

- Wine, Bobi. Uganda Zukuka. Featuring Nubian Li. Audio producer Dan Magic. Music video produced by Firebase edu-tainment. 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = qwksThBUV_Y.

- Worcester, Kent. “Comics, Comics Studies, and Political Science.” Edited by José Alaniz, Hillary L Chute, Rikke Platz Cortsen, Erin La Cour, Anne Magnussen, John A Lent, Binita Mehta, Pia Mukherji, and Daniel Worden. International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale de Science Politique 38, no. 5 (2017): 690–700.

- World Population Review. “Uganda Population 2020,” 2019. http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/uganda-population/.