ABSTRACT

In the first quarter of the twenty-first century, much future-making in Kenya is taking place in ruins of unfinished promising projects, failed capitalist enterprises, and decades of colonial and postcolonial exclusion and marginalization. When discussing future-making in Kenya specifically and Africa more generally, especially in the context of vision-driven developmentalist narratives that rely on visions of linear progress and growth, analysts and social scientists need to account for ways that futures emerge from ruins and rubble of undelivered and uncertain promises, collapsed industries, and colonial and postcolonial dispossession of land and rights. This article establishes the overarching argumentation and framing of the “Living with Ruins” special collection, outlines key theoretical concepts like ruination, infrastructuring, and future-making, and examines ruins and ruination in key economic and political domains that make claims to Kenya’s future: capitalist boom-and-bust economies, mega-scale infrastructure projects, and urban development. In all these domains, futures are emerging through assemblages of people’s everyday practices of maintenance and the ruins that surround them, complicating facile proclamations of Africa’s rising or abjection.

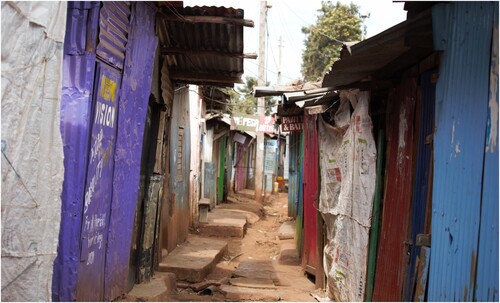

Against the backdrop of vast lush agricultural and pastoral land, the Kenyan landscape is also marked by ruins, scraps, and rubble. These include deteriorating hotels on the touristy Mombasa coast, unused pipelines around Lake Baringo, armatures of enormous flower farms at Lake Naivasha, flooded buildings of a former fish processing business in Baringo, kiosks and dwellings built from scraps in Nairobi’s informal settlements, or unfinished public office buildings on the edge of Kamariny escarpment (, , , , and ). These armatures, ruins, scraps, and skeletons of suspended projects, and the way people organize their lives around them, reveal the lingering presence of collapsed industries, stalled ambitious development projects, traces of colonial and postcolonial violence, and histories of land dispossession. They also come into sharp focus in the context of contemporary visions of Kenya’s future as a modernizing, industrialized nation. The government’s Kenya Vision 2030 development programme launched in 2008 outlines a plan to build ‘transformative and game-changer’ infrastructure in order to create prosperity and a ‘seamless connected Africa’Footnote1: superhighways, railways, airports, ports, and other large-scale structures. Some of this construction is in a planning phase, while some is ongoing. The vision and the planned infrastructure rely on the promise to shape Kenya into a ‘globally competitive and prosperous country.’Footnote2 Ruins, scraps, and rubble, however, complicate these modernist visions and narratives of progress and growth that dominate policy-making and politics in contemporary Kenya (and elsewhere).

Figure 3. A “skeleton” of the Sher Karuturi flower farm near Lake Naivasha, Kenya, 2019. Photo by Anna Lisa Ramella.

Figure 4. Buildings of a fish processing business, flooded by the expanded Lake Baringo, Kenya, 2019. Photo by Anna Lisa Ramella.

Figure 6. Unbuilt public office building, sometimes called “the governor’s house,” in Elgeyo Marakwet County, Kenya, 2019. Photo by Uroš Kovač.

This framing article and subsequent special collection examine the tension between, on the one hand, processes of ruination, and on the other, grand visions and promises of modernization and economic growth in Kenya. It investigates what it means for Kenyans to construct one’s future amidst such tension. In general, we argue that much future-making in contemporary Kenya (and arguably beyond – in eastern Africa and Africa more generally) takes place in ruins – ruins of unfinished promising projects, ruins of failed capitalist enterprises, and ruins of decades of colonial and postcolonial exclusion and marginalization. We propose that discussions of future-making in eastern Africa, and future-making in anthropology and social sciences more generally, need to account for the ways in which futures emerge from ruins and rubble of undelivered and uncertain promises, collapsed industries, and colonial and postcolonial dispossession of land and rights. We therefore argue that ruins and rubble are not passive remnants of a long-gone past, but instead vibrant material assemblages through which people imagine and construct their futures – for better or for worse. It is not the case that ruins, such as those examples listed above, belong to the past, while modernist visions that dominate policy and politics belong to the future; rather, ruins are material assemblages which people constantly use to speculate on and build their futures, sometimes by actively creating or maintaining them. It is also not the case that ruins signal only deterioration, destruction, and lost opportunities; they also signal lateral and alternative possibilities for a future, as well as uncertainty and potentials for dispossession with which people are forced to contend. They are also not an intermediary stage between, on the one hand, a past or present of dispossession, violence, and lack, and on the other, a future of prosperity and growth: ruins are not a temporary unsightly station on the one-way train towards a brighter and prosperous future. Instead, ruins and rubble are likely to remain and occasionally reappear as long-term motifs in Kenya’s future, partly because Kenyans use them to make claims to better futures for themselves, and partly because they will always stand as markers of uneven and contradictory development and modernization.

In a recent special collection, anthropologists Cassiman, Eriksen, and Meinert ask how social scientists can move beyond binary representations of precarity in sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote3 Narratives about eternal victimhood and suffering on the one hand, and those about romanticized creativity and informality on the other, are both misleading: ‘[s]o how do we move beyond such narratives while still acknowledging the precariousness of life in specific situations?’Footnote4 Analysts of states and development in eastern AfricaFootnote5 have asked similar questions in relation to narratives about, on the one hand, Africa’s ‘abjection’Footnote6 and economic lack, and on the other, Africa’s ‘rising’ as the ‘bright continent.’Footnote7 How can we account for change in Africa without romanticizing creativity in the face of uncertainty? We suggest that examining ruins, rubble, and scraps, and especially how people construct their futures in and around them, provides a useful angle on transformation in Africa: ruins and ruination are productive as objects of analysis because they signal both dispossession, exclusion, and undelivered promises, as well as lateral (sometimes unexpected) practices of future-making.Footnote8 In the sections below, we draw from recent social science theories about ruins, rubble, and infrastructure on the one hand, and about temporality and future-making on the other, in order to tease out the analytical potential of ruination amidst narratives of growth. After outlining key theoretical ideas and debates, we turn to three key areas in which futures are created, negotiated, and contested in contemporary Kenya: large-scale capitalist boom-and-bust economies, such as industrial farming and tourism; mega-projects that seek to transform rural Kenya, such as LAPSSET; and urban development that seeks to transform urban Kenya and create new urban centers, especially through building infrastructure. We show how ruins, rubble, and scraps appear in all of them, not simply as inert throwaway debris, but as resources for imagining and building a future.

Social science and its ruins

Ruins have recently become a staple of anthropological vocabulary, to the point that some have suggested that the discipline is bordering on ‘ruinophilia.’Footnote9 Ruins, and the adjacent materials and metaphors like rubble, debris, and remainders, have been predominantly treated as material remnants of the past, the decaying matter that continues to shape and obstruct people’s lives in the present and the future. Many anthropologists have been concerned not only with the ruins themselves and with their inherent properties or agency, but rather how ruins come into existence and become effective through people’s engagement with them: ruins acquire different meanings when different people live with them and reflect on them, they can contain different (often violent) histories, and they can provoke different affects. For this reason, much of anthropological work on ruins, debris, and rubble prefers to discuss ruination as a process, rather than ruins as bounded material entities. For instance, when Yael Navaro-Yashin discusses ‘ruination’ in relation to her ethnography about ruins of war in Northern Cyprus, she is referring to ‘material remains or artefacts of destruction and violation, but also to the subjectivities and residual affects that linger, like a hangover, in the aftermath of war or violence.’Footnote10 Therefore, what is at stake in discussing ruination is not only the obvious material artefacts, but rather what kinds of affects the artefacts provoke among people who live (or are forced to live) among them, and what kinds of affects people ascribe to them. In this interpretation, neither the ruins or the people are affective on their own, but both produce affect ‘relationally,’Footnote11 or in other words, through their mutual entanglement. This is important, because it allows us to emphasize that people’s relationships with ruins are not neutral, but rather politically and historically contingent: ‘“assemblages” of subjects and objects must be read as specific in their politics and history.’Footnote12 Replace ‘affect’ with ‘future-making’ and we have a decent analytical tool to examine how people imagine and build their futures by relating to ruins around them, without necessarily being overwhelmed or overdetermined by them.

It is important for analysts to resist romanticizing or over-aestheticizing ruins – all ruins are, arguably, different formations of unglamorous rubble,Footnote13 regardless of whether they are revered or not by social scientists, artists, or heritage professionals – but it is also important to recognize how they materialize different and often competing pasts in present and future lives and politics. For Joost Fontein, graves and ruins are material remnants that bring together ghosts and ancestors of different pasts and shape life and politics in the present.Footnote14 He examines the ‘discursive, historical, and material coexistences and proximities’Footnote15 of remains of different pasts that have shaped and continue to shape his fieldsite in Southern Zimbabwe – graves of chiefs and ancestors, ruins of households, or remains of hotels and irrigation schemes built by white settlers. He concludes that all these remains of different pasts continue to shape claims to autochthony and belonging in contemporary Zimbabwe: all meshed together, they create politically and historically specific ‘material landscapes of belonging,’Footnote16 i.e. landscapes filled with material remnants from different pasts that shape people’s claims of belonging to a certain clan or a piece of land. This is a crucial perspective for examining how people claim belonging in contemporary Kenya, whether for understanding how Kenyans use ruins of the past to claim belonging to particular land and resources, but also how they use remnants of colonial and postcolonial histories of exclusion, subjugation, and erasure in order to make claims to their rights to remain and continue to exist.

Perhaps most famously, Ann Stoler writes about ruins of the past as active agents in the present.Footnote17 Having focused on pasts of imperialism, colonization, and violence she strikes a decidedly critical note. For Stoler, ruination is ‘a corrosive process that weighs on the future and shapes the present’Footnote18 and ‘a political project that lays waste to certain peoples and places, relations, and things.’Footnote19 This perspective certainly applies to Kenya, where ghosts of settler colonialism continue to exclude and marginalize, for instance the urban poor in Nairobi’s informal settlements. And yet, corrosive as they are, imperial ruins can also be re-interpreted and appropriated, and ruination can be a powerful vocabulary for resistance and imagination of a more equitable future. De Jong and Valente-Quinn, for instance, document how Senegal’s ruins of colonial-era imperialist educational institutions serve as starting points for imagining pan-African education and re-imagining Afro-modernist development in the present.Footnote20 Even when these visions fail to materialize – and they almost always become distorted in the course of uneven implementation – they serve as starting points for future imaginaries and can sustain hopes for better and more just futures. Hence, ‘reappropriation of ruins enables different temporalities of ruination and regeneration.’Footnote21 Processes like appropriation and regeneration are central in contemporary Kenya, be it in informal settlements where urban poor draw from materialities of scraps and vocabularies of remainders to articulate everyday activism; or in urban life in general, where seemingly urban ruins of defunct technologies become carriers of new technologies; or even in arid rural areas where active ruination of infrastructure becomes a source of life-sustaining water. Ruins and scraps are constantly re-appropriated, and ruination, even when it stifles human flourishing, can be transformed into vitality. What is more, we find that ruination is not always an overwhelming force that displaces people and shatters their livelihoods and aspirations: in some cases, people deliberately promote, sustain, and control ruination in order to negotiate viable futures for themselves.

Capitalism plays a central role here, especially with its cycles of boom and bust. As we shall see, large capitalist projects that go through dramatic phases of growth and collapse have also considerably shaped and continue to shape Kenya. These projects also leave ruins and scraps behind them. What happens with these remains? What do Kenyans do with them? For Anna Tsing, certain forms of precarious and unexpected livelihoods can appear, and even thrive, in the ruins of large-scale capitalist exploitation.Footnote22 ‘Capitalist ruins’ here stand for exploitation of land, resources, and people that, paradoxically, make (precarious) lives and futures possible. In Tsing’s ethnography, industrial deforestation has led to emergence of matsutake mushrooms, and around them a complex web of pickers, buyers, and traders that make up an unreliable – but often exciting – global chain of supply and demand.Footnote23 Ruins of large-scale capitalist projects therefore have afterlives, opening up possibilities of (precarious) life.Footnote24 Shannon Lee Dawdy makes a similar point about ruined landscapes in the urban United States.Footnote25 Urban ruins, she argues, by themselves are material representations of capitalism’s impermanency, one which contrasts its promise of growth and progress. However, once again, unexpected and precarious futures emerge, and sometimes even thrive, among ruins and lots that are far from vacant, but instead serve as ‘opportunity zones’Footnote26 for alternative, yet precarious, livelihoods. This is a relevant insight for contemporary Kenya, where, as we shall see, large-scale capitalist boom-and-bust economies have left behind landscapes of skeletons and scraps that people continue to use to build futures. These futures might appear lateral and marginal compared to the large-scale projects or industries in whose shadows they are formed, however they are central for the people themselves.

It is clear from this overview that ruins and scraps are not simply leftovers from the past. Rather, with ruins and ruination, temporalities overlap: ghosts from the past intrude on present aspirations, and future-making projects ascribe new meanings to remains from the past. A common argument is that ethnographic attention to ruins ‘undermines the stability of modern, progressive time:’Footnote27 the presence of (modern, capitalist) ruins complicates the temporal ideology of modernity that promises linear growth and progress.Footnote28 This is an important point, especially if time in Africa is, as it has been extensively argued, an ‘interlocking of presents, pasts, and futures,’Footnote29 and if African futures are plural, non-linear, and open-ended.Footnote30 However, things are arguably even more complicated. Analysts of Africa have been excavating ruins, traces, and remains of ‘futures of the past’Footnote31 throughout the continent, namely colonial and postcolonial projects that promised prosperity through modernization: medical science institutions,Footnote32 modernist architecture,Footnote33 post-independence development initiatives,Footnote34 and colonial-inspired educational institutions.Footnote35 They have observed a continuing salience of grand narratives of growth and progress: ruins of past modernization efforts arguably keep alive the temporal ideology of modernity despite its past failures to deliver, if only through longing and nostalgia for how things could have been. Thomas Yarrow, for instance, has reflected on ruins of a 1960s resettlement scheme in Ghana to show how a modernization project failed to deliver, but also how its disappointed beneficiaries still desire its particular brand of prosperity and remain angry that they never got to experience it.Footnote36 Here ruination reveals a ‘sense of decay, fragmentation, and degradation seen through the lens of a promised future.’Footnote37 This perspective is highly relevant for contemporary Kenya, where a landscape of ruins exists amid a proliferation of renewed promises of growth and progress, an aspiration for modernity and modernization revitalized for the twenty-first century, exemplified by the vision-driven development agenda that promises to launch the country into a brighter future.Footnote38

We can take this temporal disjuncture even further. The contrast between material rubble that litters the present and spectral visions of a promised future has provoked analysts to reflect on overlapping and frankly confusing temporalities of contemporary development, especially concerning infrastructural development in the global South.Footnote39 Hence Akhil Gupta writes about half-finished infrastructures in Indian cities that slow down traffic and movement as a ‘future in rubble’ and ‘ruins of the future.’Footnote40 Here notions of ruin and rubble are completely removed from their associations with the past and are instead conceptualized as immanent to contemporary hopes for a better future. These are the ruins and rubble of half-finished construction projects, not unlike the “white elephants” visible throughout Kenya, and they are all about unstable temporalities like ‘in-between-ness’ and ‘suspension,’Footnote41 temporal states of simultaneous hope and disappointment. Rather than just leaving materials behind, these ruins accumulate; they ‘rise from the ground rather than fall from pinnacles’. Footnote42 Infrastructural development and construction boom are indeed the order of the day in contemporary Kenya, and instead of bluntly assessing whether they will bring prosperity or not, it is productive to consider what kinds of ruins and rubble they are producing and how do people engage them. What is more, disassociating ruins and rubble from past tense allows us to recognize acts of ruination that are contemporary, deliberate, and future-oriented.

Kenya and its ruins

In the following sections, we turn to empirical case studies of ruins and ruination from Kenya. These show how ruins and rubble are embedded in practices of transformation and reordering, projecting materialized pasts into contemporary practices.

Capitalist boom-and-bust economies

How do Kenyans order their lives and imagine their futures throughout capitalist cycles of boom and bust? One of the most well-researched capitalist ventures in Kenya offers some answers – the agro-industry of growing, harvesting, packing, and transporting flowers.Footnote43 Kenya is one of the largest exporters of cut flowers, especially to the European Union. Since the 1970s numerous flower farms have transformed villages around Lake Naivasha into a vibrant town and a provincial centre, a key node in the global commodity chain, and a destination to which Kenyans migrate for jobs. In a fashion typical for global capitalist dynamics of boom and bust, some flower farms and export companies are thriving, while others are collapsing. The 2010s in particular have seen collapse of many small-scale farms, but also one of three major farms, formerly Dutch-owned and later Indian-owned Sher Karuturi, which suspended operation in 2014 and in 2023 was still under receivership. In 2022, while Naivasha’s residents increasingly doubted a resale of the farm due to flooding, news spread about a potential investor who promised a return to production after eight years of inactivity.Footnote44

Ramella, Schmidt, and Styles have conducted long-term ethnographic research with Sher Karuturi employees, and asked how they dealt with uncertainties of boom and bust.Footnote45 In times of boom, the farm was a massive greenhouse structure that provided employment, housing, and decent working conditions for migrant workers. In times of bust, it turned into a massive “skeleton” – the remains of a metal structure that used to support the greenhouse plastic cover. In 2019, the huge piece of land once used to grow flowers was overcome by weeds, and the houses built for migrant workers were dilapidating. But they were not abandoned: many former employees continued to stay in the housing complex, and continued to claim their rights to payment of promised salaries and pensions. In the absence of better opportunities in their rural homes, they became “squatters” in their former houses, as they refused to leave and chose to remain and assert their rights. Crucially, they also continued to maintain the farm and its “skeleton” in a decent working order, by, for instance, removing weeds and cleaning irrigation pipes. By looking after this apparent capitalist ruin they were preventing it from appearing as a complete failure, and retaining it in a potentially attractive state for a new investor. Ramella, Schmidt, and Styles call this processes ‘suspending ruination’ – preventing what appears as a capitalist ruin to devolve into a complete collapse, while at the same time not restoring it to its original state.Footnote46 In this way, ‘suspending ruination’ means signaling the collapse of a capitalist venture while at the same time maintaining its potential for future capitalist speculation. And so, while social scientists often theorize ruination as an overwhelming, almost inevitable process that displaces people and takes away their livelihoods,Footnote47 migrant workers in Naivasha seek to actively and deliberately take control over ruination and its consequences.

But something besides maintenance was also taking place among the farm’s dilapidating structures. While the former employees continued to tie their futures to the future of the farm, they were also finding new ways to make a living through alternative livelihood strategies, or ‘lateral work arrangements.’Footnote48 For instance, they were fishing in the nearby lake, and selling fish and vegetables to workers of nearby businesses. Crucially, they were using material remnants of their former employer’s venture – an old company house to access the lake and its fish, small pieces of company’s land to grow vegetables, and old greenhouse plastic sheets to wrap vegetables and fish for sale. These lateral livelihood practices show how large-scale capitalist endeavors become intertwined with small-scale orderings of the future. Crucially, these lateral livelihoods are not future-making practices of a second order, but rather contribute to the bustling and dynamic environment that is Lake Naivasha, an environment that has attracted the workers to migrate in the first place, and that continues to attract newcomers. And so, future-making in Naivasha is characterized by an assemblage of seemingly contradicting processes, temporalities, and livelihood strategies – collapse and maintenance, large-scale export and small-scale trade, stasis and mobility, ordering and ruination.

In a pilot research project in 2020 in semi-arid lowlands of Kerio Valley, Uroš Kovač made similar observations among former mining town residents. Fluorspar, an industrial mineral used in the manufacturing of steel, aluminum, and refrigerants (among many other things), was discovered here in the 1960s. Since the beginning of mining in the 1970s, the mineral and its mining have been hailed as major sources of economic growth in the Elgeyo Marakwet County. The Kenya Fluorspar Company, owned by the Kenyan government until 1997 when it was privatized and continued to run on foreign investments, has over the decades been a stable presence in the region. It turned a nearby village of Kimwarer into a small but bustling town, directly and indirectly created jobs for thousands of Kenyans, invested in building and maintaining public facilities, and served as an epicenter for businesses like shops, hotels, and transport companies. That is, until the price of fluorspar on the global market started to dramatically fluctuate, and eventually drop. The company closed its doors in 2009, seemed to have bounced back and re-opened in 2012, but again suspended its operations in 2016. In 2022, local politicians were still promising to find new investors and revive the company and the local economy.Footnote49

When Kovač visited Kimwarer (locally often simply called “Fluorspar”) in February 2020, the place exuded abandonment: mining pits filled with dirty water, rusting excavation machinery, company premises in overgrown grass, disassembled transport lorries, and a dilapidating housing complex. And yet, the place was not abandoned. A large school, a medical centre, and a modern gym, all built by the Kenya Fluorspar Company, were still open and running, albeit at a reduced capacity. The run-down housing complex was still a home to teachers, nurses, gym instructors, and security guards. They spoke nostalgically about the town’s prosperous past, and hedged their bets on a new investor who would revive the company. They seemed particularly invested in maintaining the public facilities – school, health centre, gym – in a decent state and a working order, actively waiting and hoping for a new period of prosperity. The run-down houses and facilities thus signaled collapse and neglect, while at the same time their active maintenance signaled future potential that might attract investors. While James Ferguson’s interlocutors in Zambia’s Copperbelt felt abjected from global modernity,Footnote50 Kimwarer’s remaining residents actively waited for a new cycle of prosperity through global extractive capitalism. And like Patience Mususa recently documented in a comparable setting (once again in Zambia’s Copperbelt),Footnote51 the capitalist bust was not the end of the line for Kimwarer, but rather had an afterlife, one in which disappointment and hope coexisted and fed off one another. The assemblage of material decomposition, people’s uncertain livelihoods, and residents’ maintenance work was a precarious ‘opportunity zone’Footnote52 in which the remaining residents actively waited for a regeneration of their future, but also a site of speculation for political figures, for whom this modern ruin was a political playground for promises of revival and prosperity. Disappointment and hope mingled with material decomposition and strategic maintenance, in a suspended state of anticipation of a better future, a particular kind of future that has once already proven itself as prosperous.

One more example of capitalist boom and bust comes from one of Kenya’s internationally most visible industries: tourism, embraced by all postcolonial Kenyan governments as a driver of economic growth. Having especially grown since the 1990s, it slowed down only by occasional violence and terrorist attacks that reached international news in the 2000s and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.Footnote53 In particular, the southern Kenyan coast near Mombasa has become globally famous for sandy beaches and lavish resorts, every year attracting thousands of tourists. Instead of focusing on successful resorts, Franziska Fay examined the ruins of the once thriving Two Fishes Hotel on Diani Beach, which disturbed the landscape of economic growth on the coast.Footnote54 Here she found Kenyans who sought to chart a future and come to terms with the past in the “skeleton” (gofu in Swahili) of the dilapidating hotel, finding their bearings in the rubble amid a thriving tourist industry. Similar to migrant workers on Naivasha’s flower farm “skeleton” discussed above, here different actors built futures from the ruins of a once profitable capitalist project, by, for instance, attempting to earn a living from nostalgia-driven “ruin tourism,” claiming rights to compensation from a phantom owner, or surviving on lateral sources of income, like fishing. Notably, despite the municipal efforts to formalize land ownership on the coast, the men carved their livelihoods from the ruin’s ambiguous status – between public and private. As the world has emerged from COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions on movement that decimated the tourist industry in Kenya, Fay’s account provides a glimpse of precarious futures carved from the ruins of a capitalist bust that will likely remain less visible once the industry returns to full throttle – futures built from ambiguity, flexibility, and exclusion.

Large-scale land-intensive projects transforming rural Kenya

Large-scale development projects are reshaping contemporary Kenya, especially its rural areas. Their ambitions are formulated in the Kenya Vision 2030 development plan as promises to transform Kenya into a middle-income industrialized country. The development plan, launched in 2006, has been described as part neoliberal – driven by market deregulation, competition, and partnerships between the public and the private sector. However, it is also strongly state-driven and state-controlled, and inspired by visions of growth through high modernism. As such, it reflects visions of modernization through the “mixed economy” and “managed capitalism” of Kenya’s 1960s post-independence period.Footnote55 Kenya Vision 2030 revives 1960s visions of growth that fueled pan-Africanist and postcolonial nation-building, combined with decades of experience with neoliberal public-private intersections.

A major element of the state’s development agenda is the building of “transformative” infrastructure, whose construction and planning is reshaping rural Kenya. The most prominent example is LAPSSET, a flagship project and an infrastructural corridor, that in theory will include a seaport, an airport, a resort, highways, and oil pipelines. So far it has mostly been realized on paper and in planning boardrooms, but its announcement is already re-shaping Kenya’s towns and rural areas through people’s ‘economies of anticipation.’Footnote56 In particular, since LAPSSET corridors are planned to cut across arid regions, the infrastructural visions and promises have been making waves in parts of northern Kenya at least partly populated by pastoralist groups.Footnote57 Pastoralist areas have been subject to substantial economic and political changes since at least the 1990s,Footnote58 and now change is being accelerated by such announcements. Namely, the “game-changer” infrastructure project promises to transform “remote” parts of northern Kenya, to “bring in” the neglected parts of the country into modernity and modernization, and to “develop” pastoralist areas and effectively eliminate long-lasting economic disparities between northern Kenya and the rest of the country. The results and consequences of these visions remain to be seen. Unsurprisingly, scholars have already made convincing arguments that LAPSSET is at least partly being built on the ‘ruins of empire:’Footnote59 while contemporary and colonial-era development visions are certainly not the same, they are similar in the framing of northern Kenya as an isolated and untapped resource full of underexploited potential, and the plan to immobilize pastoralists’ livelihoods in the name of development.Footnote60

Building on these studies, David Greven examined what happens when modernizing visions “break the ground” in northern Kenya by investigating the newly built pipes and water points designed to bring water to arid areas of East Pokot.Footnote61 The water pipeline is a part of a geothermal exploration project that seeks to exploit the area for green energy, while also promising reliable provision of water to pastoralists. The provision of water infrastructure was however patchy, leading to ‘reliable leakages’Footnote62 along the pipeline. Some of the leakages – those that Greven calls ‘the condition of ruination’Footnote63 – were anticipated by the geothermal company, but consistent maintenance of pipes was expensive and often not forthcoming. The leakages were also fairly reliable to local pastoralists, since access to water at the leakages was no less predictable than at the water points designed to deliver water in the first place. Other leakages – those that Greven calls ‘acts of ruination’Footnote64 – resulted from locals’ deliberate destruction of pipes, sometimes as a form of protest, and sometimes as a claim of entitlement to infrastructure built on communal land. What is more, the residents increasingly congregated and organized their economic and political lives around the leakages, namely by watering their animals, opening shops, and forming committees to address risks of bursting pipes. The residents therefore used the leakages to access the scarce water, as well as to make claims to the geothermal company to fix and maintain the pipeline. On the surface, the leakages represented infrastructure that is ‘always already on the way to becoming ruins,’Footnote65 however people relied on ruination, at times more than on the infrastructure itself.

Once again, as discussed earlier, people attempt to engage and appropriate large-scale projects for their own use, and their ‘lateral’Footnote66 and unintended uses are not marginal, but often crucial, and no less reliable. In East Pokot, ruination is a process that is hardly avoidable as infrastructure’s materiality deteriorates in “unruly” landscapes, but it is also a deliberate action by which people negotiate and claim the project, often in unanticipated ways. Moreover, people indeed congregate and build economic lives around the infrastructure, just as envisioned by Vision 2030 corridor planners; however, when leakages and broken pipes become congregating points for pastoralists and their animals, it is not only the infrastructure itself that drives local economies, but also its ruination. Here ruination is not a leftover from the past that impinges on the present and the future, but rather a contemporary process, sometimes deliberate, and while it brings new risks, people seek to appropriate and control it in order to access a vital resource.

In northern Kenya and elsewhere, infrastructure and construction projects like LAPSSET take up an enormous amount of space and require large swaths of land. Unsurprisingly, they come with issues of land-use, evictions, compensations for relocation, and politics of belonging.Footnote67 Returning briefly to Elgeyo Marakwet County, the controversial Arror and Kimwarer mega-dams whose construction was announced in 2016 but suspended in 2019 due to allegations of corruption were deeply entangled with complications over land. According to a representative of the Community Based Organization (CBO) for the Kimwarer dam whom Kovač interviewed in February 2020, people were excited about the promises the mega-dam offered: employment, electricity, tourism, and irrigated agriculture. However, around 200 families were to be displaced from their lands to make space for the dam, and they complained that no clear compensation plan had been laid out for them. Some were allegedly suspicious of promises for compensation because, as they claimed, their family elders have never been appropriately compensated for displacement from their “ancestral” lands that the government and companies used for decades to mine fluorspar. At the time of writing, the construction of the Kimwarer dam was indefinitely suspended.Footnote68

How do groups and individuals make claims to particular pieces of land? Ruins and material debris from the past may play a role, as Léa Lacan demonstrates, albeit through a story of nature conservation, that other land-intensive process that is re-shaping rural Kenya.Footnote69 Through archival and ethnographic research, Lacan investigated the transformation of Baringo County’s Katimok Forest into a forest reserve, and the evictions of the forest’s dwellers, by colonial and postcolonial governments. She found that, nowadays, the descendants of forest dwellers point to the ruins of the past – such as abandoned hearth stones and graves of family elders – and material indicators of past dwellings – such as traces of farming activities and cuts in tree bark – to tell stories of transgenerational belonging. In this way, the descendants use the ruins and the traces as material anchors to the Katimok Forest, actively creating and maintaining a collective identity, and making strong claims of belonging to the forest. Here we find imperial (and post-imperial) ruination that ‘lays waste to certain peoples’Footnote70 through displacement, as well as ruins of past generations’ lives,Footnote71 both of which combine to make people’s sense of belonging a tangible and embodied experience, much more than an abstract recollection. Engagement with ruins and traces keeps memories of displacement alive, and turns belonging into an affective and material everyday experience.

But there is more – the descendants do not only dwell on the past. They make legal appeals to be recognized as transgenerational victims of evictions and entitled to compensation in the form of land or money. Crucially, they point to ruins and traces in the forest to make such appeals legible and convincing. Here a material sense of belonging turns into a transgenerational politics of belonging, and a claim for the future of recognition. Ruins and traces therefore play a key role in people’s future-making, in what Lacan calls ‘ruins [as] material proofs.’Footnote72 Justice has proven to be elusive for Katimok Forest descendants, but hope still remains. The story is a potent example of how people use remains from the past to make affective (and potentially effective) claims to pieces of land, a key issue in contemporary Kenya’s reality of land-grabbing and land-claiming by different political actors.

Urban development and infrastructure

Besides transforming rural areas, Kenya Vision 2030 also promises rapid and radical urban development. In particular, it proposes to transform Nairobi into a ‘world class African metropolis.’ The documents that outline visions of Nairobi’s transformation, developed by international consulting companies in collaboration with the Kenyan government, resemble similar urban regeneration plans developed for other African cities in the last two decades. These plans reflects the notion that African cities are the “last frontier” of international property development, in line with a broader “Africa rising” narratives. In these plans, three-dimensional computer models project images of smart cities, eco cities, and uncongested streets, inspired by financial capitals like Shanghai, Singapore, and Dubai. The projected image of an African metropolis is a specific, high-modernist one, radically different from heterogenous urban realities of contemporary Nairobi. Some of these urban fantasies exist only on paper and in computer models, however some construction projects have broken ground, with unpredictable results. Unsurprisingly, scholars and journalists have already raised pertinent questions: who will belong to this projected metropolis, who stands to benefit from its construction, and will it usher new forms of exclusion and marginalization of the urban poor.Footnote73

A key promise of this particular form of urban development is that it will elevate Kenya’s global status as a node in transnational circulation of people and capital: Kenya’s cities, especially Nairobi and its surroundings, are to become centres of global capitalism. One example is Konza Tech City, a proposed “smart city” under construction in a savannah 60 kilometers from Nairobi. Announced by the Kenyan government in 2008, the hyper-modern technopolis is intended to become Kenya’s “Silicon Savannah,” a regional IT hub. Its key orientation is global: the smart city is designed to attract foreign investors and multinational companies, especially Western and Asian technology firms. The firms are to be attracted by tax exemptions and access to large swaths of land, and in return should deliver tens of thousands of new jobs, efficient data-driven infrastructure, and billions of dollars to the Kenyan economy. In 2023, the construction of the smart city, touted in 2008 by the Kenyan government as the ‘best-planned’ city in Africa, is far behind schedule, and it is especially unclear how it will relate to regional residents who will certainly not be able to afford housing in the new hyper-modern city. Journalist Carey Baraka assesses: ‘Konza is on track to become an exemplar of bubble urbanism, a secure, high-tech enclave away from the choked urban atmosphere of the capital. … [I]t will be a hub for global capital – a city created to suit the interests of influential multinationals.’Footnote74 The city’s stalled construction has already spurred new economies of anticipation in the region, where residents scramble to acquire land titles, build permanent houses in strategic locations, and broker land ownership deals with future middle and upper class owners, in an attempt to insert themselves into an urban future that is looking to exclude them.Footnote75

The logic of construction for the sake of global connectivity is not exclusive to urban centres. One example from Elgeyo Marakwet County comes in the form of a stalled and politicized construction of a lavish international stadium, a few kilometers from the county capital Iten, a town internationally famous for launching careers of some of the most famous Kenyan long-distance runners. The new stadium, designed by Vision 2030 planners to replace an old running track, was meant to host international sports competitions, and attract (even more) visitors and foreign capital to the athletics hub. Even setting aside the heated discussions among athletes and planners about the shape and use of the proposed sports infrastructure,Footnote76 the construction was mostly characterized by delays, stalling, and uncertainty. Like with many other ambitious projects in Kenya, it was started and then indefinitely suspended, leaving behind ruins and scattered materials. The training ground for athletes was now covered in rubble of dug-out pipes and scattered stones, the leftover cement and scattered iron rods needed guarding and kept unpaid caretakers chained to the construction site, and a proposed public office building on the site was half-finished and left to decay into a ruin as a result of local residents’ protests and accusations of corruption. These were not rubble and ruins of the past, but of unfinished projects and undelivered promises.Footnote77 Here ‘half-built ruins’Footnote78 can signify uneven development, but also possibilities for protest and contestation. And while the construction was supposed to bring global capital and a modernist future, it also threatened to turn a famous and useful piece of infrastructure into a ruin.

Meanwhile, in Nairobi, ruins, rubble, and decay characteristic of congested urban areas and informal settlements stand in stark contrast to images of shiny urban fantasies that stare at the citizens from Vision 2030 billboards. Underprivileged urbanites are often aware that they will likely be excluded from the projected hypermodern city, and voice pertinent critiques of urban development, however many are still emotionally invested in the fantasy and try their best to insert themselves into it. In particular, as Constance Smith shows, the envisioned urban development intends to combat urban decay by doing away with accumulated dirt – mud, rubbish, broken-down infrastructure – of informal settlements and lower income neighborhoods, and while some residents appreciate the possibility of a cleaner future, many anticipate that the clean-up will also involve their eviction.Footnote79 Here, Smith argues, ruination, understood as a force that displaces undesired people and things,Footnote80 might have less to do with decaying buildings and infrastructure, and more with the elimination of accumulated dirt and decay that continues to shape the city, especially its informal elements.Footnote81

Ruins and ruination of urban life is precisely what Prince Guma addresses when he writes about dilapidating structures of mobile phone and Mpesa kiosks, apparent ruins that populate the urban landscape of Nairobi.Footnote82 These transient structures are often shunned by urban planners as polluting elements unbecoming for the metropolis of the future that need to be done away with. However, as old communication technologies become obsolete and new ones proliferate, the kiosks do not disappear, but are rather constantly re-used and re-appropriated by urbanites who like them for their flexibility and convenience. As such, they play a key part in informal economies that serve the urban lives of Nairobians. Furthermore, since the kiosks do not depend on a classic grid infrastructure, their continued existence and necessity for urban life also suggests another kind of ongoing ruination of more conventional infrastructure. After all, Nairobi is a city with “slum upgrading” projects where high-rise buildings are built in informal settlements to replace temporary shacks and shanties, but eventually fall far short from providing enough housing units to the residents.Footnote83 Here dilapidating kiosks (and their counterparts – shacks, shanties, and micro-stalls) represent future-making possibilities from unexpected places that demand flexibility and improvisation, structures and infrastructures that make survival possible for poor urbanites, as well as the shortcomings of top-down planning that nominally prefers the benefits of conventional urban infrastructure but continually fails to deliver on a meaningful scale.

Nairobi’s informal settlements, which house more than 50% of the capital’s residents, deserve more attention: Wangui Kimari focuses on Mathare.Footnote84 She describes resilient residents who build their houses from scraps, and see themselves as ‘people who remain’ (Matigari), all while being perceived as ruining the image of a modern and prosperous Kenya. Ruin is here a suitable metaphor to understand how urban planners frame informal settlements and their residents as an uncomfortable stain on a city that aspires to future visions of a “world-class city.” Here the informal settlement of Mathare is constructed as a ruin and an ‘anti-city,’Footnote85 in contrast to Nairobi’s and its city planners’ aspirations to spectacular developmental visions. Mathare is framed as a ruin of Nairobi: Mathare residents’ dwellings are built from scraps and debris, its materials are continuously decomposing and being reused elsewhere, and its residents themselves (who have lived in Mathare for decades) are (biological, embodied) relics of long-term and enduring structural violence. Ruins and relics are suitable metaphors to show how Mathare and its residents remind the public about enduring colonial and postcolonial structural processes of ruination that reproduce urban poverty.

What is more, while ruins and relics are useful metaphors to understand long-term marginalization of the urban poor, they also allow us to understand how “slum” residents appropriate imagery of ruination and waste that has been imposed on them and their dwellings, and how they assert their right to remain and resist being erased as an unwanted by-product of urban development. Kimari’s point about a right to remain is especially poignant: Mathare and its residents refuse to disappear, despite nine decades of colonial and postcolonial systemic violence and ruination.Footnote86 By seeing themselves as Matigari, ‘those who remain,’ they construct a politicized self-identity, inspired by a book by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o about a former Mau Mau fighter and drawing on the history of Mathare as a battlefield of anticolonial protest. Matigari is therefore a descriptor of consequences of long-term systemic ruination, but also a powerful political call to action that reflects both abandonment and possibility.

Conclusion

It is important to re-iterate what this special collection (including this framing article) is not. Firstly, it is not a pessimistic statement that Kenya’s future (or present) is in ruins, as in that Kenya is facing a bleak future of ruination and collapse. It is rather an attempt to understand how futures can emerge in spaces neglected or forgotten by policy and politics, or rendered decimated by social theory, and how people seek to take control over ruins and processes of ruination in their everyday lives and construct viable futures. Conversely, it is not an optimistic statement, by which people’s dealings with uncertainty and uneven development is a cause for an uncritical celebration of creativity and improvisation. It is rather an attempt to understand how people struggle to make futures with the ruins they have been left with, or rein in processes of ruination in order to negotiate futures for themselves: ruins and ruination are equally central to future-making as development visions and agendas. Finally, it is not a statement that is exclusive to Kenya: as a vast literature shows, ruins and ruination (and adjacent materials and metaphors like scraps and rubble) are staple materials and processes in different corners of the world, including eastern Africa,Footnote87 Africa more generally,Footnote88 and practically everywhere else.Footnote89 Rather, focusing on Kenya allows us to zoom in on key economic and political processes in the country in which futures are intensively negotiated, and examine them ethnographically, in detail, in order to make points grounded in concrete empirical evidence.

Unpredictable extractive economies, large-scale infrastructural developments, nature conservation policies, urban regeneration efforts: in all these key future-making domains, Kenyans deal with ruins, scraps, and rubble. While policy and politics often promise modernist visions of linear progress and growth, it is rather these waste-like remains that shape people’s everyday experiences of rapid change. While in the context of developmentalist visions of modernization the ruins and remainders appear as a ‘matter out of place,’Footnote90 or carriers of a past that need to be removed to make way for a future, they are often key starting points for people’s speculations about different futures. Sometimes they are crucial in making feelings of belonging more concrete, and making claims to continue to belong legible and convincing. And while they signal neglect and dispossession, as well as uneven development, they are also subject to re-appropriation and re-use, and lateral (but no less significant) livelihood and future-making strategies, for better or for worse, out of will or out of necessity. As metaphors, ruins and remainders signal structural and long-term dispossession and exclusion, but can also be powerful rallying points to demand more equitable futures. Finally, ruination as a process, while corrosive and violent, is not always overwhelming, as people seek to take control over it, and sometimes even deliberately promote it, in order to negotiate viable futures for themselves. Futures in Kenya, as in many other corners of the world, are ‘emerging’Footnote91 through assemblages of people’s everyday practices and ruins that surround them, complicating facile proclamations of Africa’s rising or abjection.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank first and foremost the authors of our special collection “Living with Ruins: Ruination and Future-making in Kenya (and beyond)” for their valuable contributions and input throughout the course of this publication project. This project started with a workshop in March 2019 at the British Institute in Easter Africa (BIEA) in Nairobi, and we would like to thank BIEA for their hospitality and support, as well as additional participants of the workshop, namely Prince Guma and Eric Kioko. We are particularly thankful to the two reviewers for providing useful comments, to a reviewer who commented on the entire collection, and not least to the editors of JEAS for the opportunity to frame our collection with this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority. http://www.lapsset.go.ke/. Accessed 25 April 2023.

2 Kenya Vision 2030. https://vision2030.go.ke/. Accessed 25 April 2023.

3 Cassiman, Eriksen, and Meinert, “Introduction.”

4 Ibid, 3.

5 For example: Di Nunzio, The Act of Living; Mains, Under Construction.

6 Ferguson, Expectations of Modernity.

7 Olopade, The Bright Continent.

8 For example: De Boeck, “Inhabiting Ocular Ground;” Ramella, “Material Para-Sites.”

9 Archambault, “Concrete Violence,” 50.

10 Navaro-Yashin, “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects,” 5.

11 Ibid, 14, emphasis in original.

12 Navaro-Yashin, “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects,” 9.

13 Gordillo, Rubble, 10.

14 Fontein, “Graves, Ruins, and Belonging.”

15 Ibid, 707.

16 Ibid, 714.

17 Stoler, “Imperial Debris.”

18 Ibid, 194.

19 Ibid, 196.

20 De Jong and Valente-Quinn, “Infrastructures of Utopia.”

21 Ibid, 333.

22 Tsing, Mushroom.

23 Ibid.

24 See also Mususa, There Used to Be Order.

25 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthopology.”

26 Ibid, 776.

27 Ibid, 762.

28 See also Mususa, “There Used To Be Order”, 104.

29 Mbembe, On the Postcolony, 16.

30 Goldstone and Obarrio, African Futures.

31 Geissler and Lachenal, “Brief Instructions,” 16.

32 Geissler et al. Traces of the Future; Geissler, “Parasite Lost;” Prince, “From Russia With Love.”

33 Berre, Geissler, and Lagae, African Modernism.

34 Gez, Fouéré, and Bulugu, “Telling Ruins.”; Derbyshire and Lowasa, “The Ruins of Turkana.”

35 De Jong and Valente-Quinn, “Infrastructures of Utopia.”

36 Yarrow, “Remains of the Future.”

37 Ibid, 585, our emphasis.

38 Smith, Nairobi in the Making.

39 Anand, Gupta, and Appel, The Promise of Infrastructure; Carse and Kneas, “Unbuilt and Unfinished;” De Boeck, “Inhabiting Ocular Ground;” Harms, Luxury and Rubble.

40 Gupta, “The Future in Ruins,” 65.

41 Ibid, 70.

42 Tousignant, “Half-Built ruins”, 35.

43 Gemählich, Kenyan Cut Flower Industry; Kuiper, Agro-Industrial Labour; Styles, Roses from Kenya.

44 See: Macharia Mwangi, “Eight years on, collapse of Karuturi flower farm haunts Naivasha town,” Nation, 5 April 2022. https://nation.africa/kenya/business/eight-years-on-collapse-of-karuturi-flower-farm-haunts-naivasha-town-3771014; George Murage, “Shalimar flower farm to take over Karuturi flowers,” The Star, 28 November 2022. https://www.the-star.co.ke/business/kenya/2022-11-28-shalimar-flower-farm-to-take-over-karuturi-flowers/. Accessed 25 April 2023.

45 Ramella, Schmidt, and Styles, “Suspending Ruination” (this collection).

46 Ibid.

47 Gordillo, Rubble; Stoler, “Imperial Debris.”

48 Ramella, Schmidt, and Styles, “Suspending Ruination” (this collection), 12; See also Ramella, “Material Para-Sites.”

49 See: Mathews Ndanyi, “Kimwarer, Arror dams and fluorspar firm dominate campaigns in Elgeyo Marakwet,” The Star, 11 July 2022. https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/rift-valley/2022-07-11-kimwarer-arror-dams-and-fluorspar-firm-dominate-campaigns-in-elgeyo-marakwet/; The Star, “Revive fluorspar mining to lift economy – Rotich,” 14 September 2022. https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/rift-valley/2022-09-14-revive-fluorspar-mining-to-lift-economy--rotich/; Fred Kibor, “Kimwarer residents ask State to reopen fluorspar mines after eight-year lull,” Nation, 16 February 2023. https://nation.africa/kenya/counties/elgeyo-marakwet/kimwarer-residents-ask-state-to-reopen-fluorspar-mines-after-eight-year-lull-4126476. Accessed 25 April 2023.

50 Ferguson, Expectations of Modernity.

51 Mususa, There Used to Be Order.

52 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthopology,” 776.

53 Meiu, Ethno-Erotic Economies, 255-256, note 5.

54 Fay, “The Politics of Skeletons” (this collection).

55 Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations;” Fourie, “Model Students.”

56 Cross, “The Economy of Anticipation.”

57 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods, and Belonging;” Elliott, “Planning, Property and Plots;” Kochore, “The Road to Kenya;” Mkutu, Müller-Koné, and Owino, “Future Visions, Present Conflicts.”

58 Greiner, “Land-Use Change.”

59 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 194.

60 Aalders, “Building on the Ruins;” Enns and Bersaglio, “On the Coloniality.”

61 Greven, “Bursting Pipes” (this collection).

62 Ibid, 9.

63 Ibid.

64 Ibid, 14.

65 Gupta, “The Future in Ruins,” 62.

66 Ramella, Schmidt, and Styles, “Suspending Ruination” (this collection), 12.

67 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods, and Belonging;” Elliott, “Planning, Property and Plots;” Greiner, “Land-Use Change;” Kochore, “The Road to Kenya;” Mkutu, Müller-Koné, and Owino, “Future Visions, Present Conflicts.”

68 See: Barnabas Bii, "Land pay pain for Arror, Kimwarer residents after mega dams project stall," Business Daily, 5 January 2022. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/data-hub/land-pay-pain-for-arror-kimwarer-residents-dams-project-stall-3672418; Dauti Kahura and Lorenzo Bagnoli, "Arror and Kimwarer: Theft on a Grand Scale," The Elephant, 11 April 2022. https://www.theelephant.info/features/2022/04/11/arror-and-kimwarer-theft-on-a-grand-scale/. Accessed 25 April 2023.

69 Lacan, “In the Ruins” (this collection).

70 Stoler, “Imperial Debris,” 196.

71 Fontein, “Graves, Ruins, and Belonging.”

72 Lacan, “In the Ruins” (this collection), 10.

73 Smith, Nairobi in the Making; Baraka, “The Failed Promise;” Watson, “African Urban Fantasies.”

74 Baraka, “The Failed Promise.”

75 Van den Broeck, “We Are Analogue.”

76 Kovač, “A Place for Training.”

77 Gupta, “The Future in Ruins;” Harms, Luxury and Rubble.

78 Tousignant, “Half-Built Ruins.”

79 Smith, Nairobi in the Making.

80 Stoler, “Imperial Debris.”

81 Smith, Nairobi in the Making, 77.

82 Guma, “Incompleteness of Urban Infrastructures;” Guma, “Recasting Provisional Urban Worlds.”

83 Guma, “Recasting Provisional Urban Worlds,” 218–219.

84 Kimari, “Resisting Imperial Erasures” (this collection).

85 Ibid, 6.

86 Ibid, 3ff.

87 Aalders, “Building on the Ruins;” Gez, Fouéré, and Bulugu, “Telling Ruins;” Mains, Under Construction.

88 Archambault, “Concrete Violence;” Berre, Geissler, and Lagae, African Modernism;” Geissler et al, Traces of the Future.

89 Alexander and Reno, Economies of Recycling; Harms, Luxury and Rubble; Olsen and Pétursdóttir, Ruin Memories; Stoler, Imperial Debris.

90 Douglas, Purity and Danger.

91 Péclard, Kernen, and Khan-Mohammad, “États d’émergence;” Rubin, Fioratta, and Paller, “Ethnographies of Emergence;” Van Wolputte, Greiner, and Bollig, “Futuring Africa.”

Bibliography

- Aalders, Johannes Theodor. “Building on the Ruins of Empire: The Uganda Railway and the LAPSSET Corridor in Kenya.” Third World Quarterly 42, no. 5 (2021): 996–1013. doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1741345.

- Alexander, Catherine, and Joshua Reno, eds. Economies of Recycling: The Global Transformation of Materials, Values and Social Relations. London: Zed Books, 2012.

- Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, eds. The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Archambault, Julie Soleil. “Concrete Violence, Indifference and Future-Making in Mozambique.” Critique of Anthropology 41, no. 1 (2021): 43–64. doi:10.1177/0308275X20941573.

- Baraka, Carey. “The Failed Promise of Kenya’s Smart City.” Rest of World. June 1, 2021. https://restofworld.org/2021/the-failed-promise-of-kenyas-smart-city/#:~:text = While%20the%20government%20promised%20that,the%20country’s%20average%20annual%20income, 2021.

- Berre, Nina, Paul Wenzel Geissler, and Johan Lagae, eds. African Modernism and Its Afterlives. Bristol: Intellect, 2022.

- Carse, Ashley, and David Kneas. “Unbuilt and Unfinished: The Temporalities of Infrastructure.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 10, no. 1 (2019): 9–28. doi:10.3167/ares.2019.100102.

- Cassiman, Ann, Thomas Hylland Eriksen, and Lotte Meinert. “Introduction: Beyond Precarity in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Anthropology Today 38, no. 4 (2022): 3–3. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12739.

- Chome, Ngala. “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging: Negotiating Change and Anticipating LAPSSET in Kenya’s Lamu County.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020): 310–331. doi:10.1080/17531055.2020.1743068.

- Cross, Jamie. ““The Economy of Anticipation: Hope, Infrastructure, and Economic Zones in South India.” Comparative Studies of South Asia.” Africa and the Middle East 35, no. 3 (2015): 424–437. doi:10.1215/1089201X-3426277.

- Dawdy, Shannon Lee. “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity.” Current Anthropology 51, no. 6 (2010): 761–793. doi:10.1086/657626.

- De Boeck, Filip. “Inhabiting Ocular Ground: Kinshasa’s Future in the Light of Congo’s Spectral Urban Politics.” Cultural Anthropology 26, no. 2 (2011): 263–286. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2011.01099.x.

- De Jong, Ferdinand, and Brian Valente-Quinn. Infrastructures of Utopia: Ruination and Regeneration of the African Future. Africa: Cambridge University Press, 2018. doi:10.1017/S0001972017000948.

- Derbyshire, Samuel F., and Lucas Lowasa. “The Ruins of Turkana: An Archaeology of Failed Development in Northern Kenya.” In African Modernism and Its Afterlives, edited by Nina Berre, Paul Wenzel Geissler, and Johan Lagae, 267–282. Bristol: Intellect, 2022.

- Di Nunzio, Marco. The Act of Living: Street Life, Marginality, and Development in Urban Ethiopia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

- Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966.

- Elliott, Hannah. “Planning, Property and Plots at the Gateway to Kenya’s ‘New Frontier’.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 511–529. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266196.

- Enns, Charis, and Brock Bersaglio. “On the Coloniality of ‘New’ Mega-Infrastructure Projects in East Africa.” Antipode 52, no. 1 (2020): 101–123. doi:10.1111/anti.12582.

- Fay, Franziska. “The Politics of Skeletons and Ruination: Living (with) Debris of the Two Fishes Hotel in Diani Beach, Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 17, no. 1–2 (2023): 222–240. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2231789.

- Ferguson, James. Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Fontein, Joost. “Graves, Ruins, and Belonging: Towards an Anthropology of Proximity.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 17 (2011): 706–727.

- Fourie, E. “Model Students: Policy Emulation, Modernization, and Kenya’s Vision 2030.” African Affairs 113, no. 453 (2014): 540–562. doi:10.1093/afraf/adu058.

- Geissler, Paul Wenzel, and Guillaume Lachenal. “Brief Instructions for Archaeologists of African Futures.” In Traces of the Future: An Archaeology of Medical Science in Africa, edited by Paul Wenzel Geissler, Guillaume Lachenal, John Manton, and Noémi Tousignant, 14–30. Bristol: Intellect, 2016.

- Geissler, Paul Wenzel. “Parasite Lost: Remembering Modern Times with Kenyan Government Medical Scientists.” In Evidence, Ethos and Experiment: The Anthropology and History of Medical Research in Africa, edited by Paul Wenzel Geissler, and Catherine Molyneux, 297–232. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2011.

- Geissler, Wenzel Paul, Guillaume Lachenal, John Manton, and Noémi Tousignant, eds. Traces of the Future: An Archaeology of Medical Science in Africa. Bristol: Intellect, 2016.

- Gemählich, Andreas. The Kenyan Cut Flower Industry & Global Market Dynamics. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, Limited, 2022.

- Gez, Yonatan N., Marie Aude Fouéré, and Fabian Bulugu. “Telling Ruins: The Afterlives of an Early Post-Independence Development Intervention in Lake Victoria, Tanzania.” Journal of Modern African Studies 60, no. 3 (2022): 345–370. doi:10.1017/S0022278X22000180.

- Goldstone, Brian, and Juan Obarrio, eds. African Futures: Essays on Crisis, Emergence, and Possibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226402413.001.0001.

- Gordillo, Gastón R. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

- Greiner, Clemens. “Land-Use Change, Territorial Restructuring, and Economies of Anticipation in Dryland Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 530–547. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266197.

- Greven, David. “Bursting Pipes and Broken Dreams: On Ruination and Reappropriation of Large-Scale Water Infrastructure in Baringo County, Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 17, no. 1–2 (2023): 241–261. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2231790.

- Guma, Prince K. “Incompleteness of Urban Infrastructures in Transition: Scenarios from the Mobile Age in Nairobi.” Social Studies of Science 50, no. 5 (2020): 728–750. doi:10.1177/0306312720927088.

- Guma, Prince K. “Recasting Provisional Urban Worlds in the Global South: Shacks, Shanties and Micro-Stalls.” Planning Theory and Practice 22, no. 2 (2021): 211–226. doi:10.1080/14649357.2021.1894348.

- Gupta, Akhil. “The Future in Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure.” In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, 62–79. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Harms, Erik. Luxury and Rubble: Civility and Dispossession in the New Saigon. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

- Kimari, Wangui. “Resisting Imperial Erasures: Matigari Ruins and Relics in Nairobi.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 17, no. 1–2 (2023): 207–221. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2231787.

- Kochore, Hassan H. “The Road to Kenya?: Visions, Expectations and Anxieties Around New Infrastructure Development in Northern Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 494–510. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266198.

- Kovač, Uroš. “‘A Place for Training, not for Competition:’ Negotiations of Competition and Agency Among Long-Distance Runners in Kenya.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 29, no. 3 (2023): n/a–n/a.

- Kuiper, Gerda. Agro-Industrial Labour in Kenya: Cut Flower Farms and Migrant Workers’ Settlements. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

- Lacan, Léa. “In the Ruins of Past Forest Lives: Remembering, Belonging and Claiming in Katimok, Highland Rural Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 17, no. 1–2 (2023): 186–206. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2231786.

- Mains, Daniel. Under Construction: Technologies of Development in Urban Ethiopia. Durham: Duke University Press, 2019.

- Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Meiu, George Paul. Ethno-Erotic Economies: Sexuality, Money, and Belonging in Kenya. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- Mkutu, Kennedy, Marie Müller-Koné, and Evelyne Atieno Owino. “Future Visions, Present Conflicts: The Ethnicized Politics of Anticipation Surrounding an Infrastructure Corridor in Northern Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 15, no. 4 (2021): 707–727. doi:10.1080/17531055.2021.1987700.

- Mosley, Jason, and Elizabeth E. Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199.

- Mususa, Patience. There Used to Be Order: Life on the Copperbelt After the Privatisation of the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. “Affective Spaces, Melancholic Objects: Ruination and the Production of Anthropological Knowledge.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15, no. 1 (2009): 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.01527.x.

- Olopade, Dayo. The Bright Continent: Breaking Rules and Making Change in Modern Africa. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014.

- Olsen, Bjørnar, and Þóra Pétursdóttir, eds. Ruin Memories: Materialities, Aesthetics and the Archaeology of the Recent Past. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Péclard, Didier, Antoine Kernen, and Guive Khan-Mohammad. “États D’émergence. Le Gouvernement de La Croissance et Du Développement En Afrique.” Critique Internationale 89, no. 4 (2020): 9–27. doi:10.3917/crii.089.0012.

- Prince, Ruth J. “From Russia With Love: Medical Modernities, Development Dreams, and Cold War Legacies in Kenya, 1969 and 2015.” Africa 90, no. 1 (2020): 51–76.

- Ramella, Anna Lisa, Mario Schmidt, and Megan Styles. “Suspending Ruination: Preserving the Ambiguous Potentials of a Kenyan Flower Farm.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 17, no. 1–2 (2023): 165–185. doi:10.1080/17531055.2023.2231785.

- Ramella, Anna Lisa. “Material Para-Sites: Lateral Future-Making in Times of Fragility.” Etnofoor 32, no. 1 (2020): 42–60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26924849.

- Rubin, Joshua D, Susanna Fioratta, and Jeffrey W Paller. “Ethnographies of Emergence: Everyday Politics and Their Origins Across Africa Introduction.” Africa 89, no. 3 (2019): 429–436. doi:10.1017/S0001972019000457.

- Smith, Constance. Nairobi in the Making: Landscapes of Time and Urban Belonging. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2019. doi:10.2307/j.ctvfrxrms.

- Stoler, Ann Laura, ed. 2013. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 2 (2008): 191–219. doi:10.1525/can.2008.23.2.191.

- Styles, Megan A. Roses from Kenya: Labor, Environment, and the Global Trade in Cut Flowers. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019.

- Tousignant, Noémi. “Half-Built Ruins.” In Traces of the Future: An Archaeology of Medical Science in Africa, edited by Paul Wenzel Geissler, Guillaume Lachenal, John Manton, and Noémi Tousignant, 35–38. Bristol: Intellect, 2016.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Broeck, Van den. “‘We Are Analogue in a Digital World’: An Anthropological Exploration of Ontologies and Uncertainties Around the Proposed Konza Techno City Near Nairobi, Kenya.” Critical African Studies 9, no. 2 (2017): 210–225. doi:10.1080/21681392.2017.1323302.

- Van Wolputte, Steven, Clemens Greiner, and Michael Bollig. “Futuring Africa: An Introduction.” In African Futures, edited by Clemens Greiner, Steven Van Wolputte, and Michael Bollig, 1–16. Leiden: Brill, 2022. doi:10.1163/9789004471641_002.

- Watson, Vanessa. “African Urban Fantasies: Dreams or Nightmares?” Environment and Urbanization 26, no. 1 (2014): 215–231. doi:10.1177/0956247813513705.

- Yarrow, Thomas. “Remains of the Future: Rethinking the Space and Time of Ruination Through the Volta Resettlement Project, Ghana.” Cultural Anthropology 32, no. 4 (2017): 566–591. doi:10.14506/ca32.4.06.