ABSTRACT

The article provides a framework through which to analyse the experiences and social trajectories of migration from East Africa to North Africa and Europe. On the one side, it explores the systematic relationship between war and mobility, and on the other, it highlights the social worlds generated by such mobility. The article argues that these social worlds represent crucial elements for understanding contemporary (Eastern) African societies and their political dynamics, in relation to (a) the increased relevance of migration diplomacy, (b) the spatial interconnectivity constructed through mobility and (c) the transnational and diasporic spheres that lie at the core of the social and economic reproduction of states and societies in the Horn and more generally in Eastern Africa. We highlight, through these interconnections, the genealogies and transformations of the systems of violence composing the reality of migration in the regions explored, but also the various and interconnected systems of solidarity which, although fragmented and even misused at times, sustain migrants’ trajectories, social projects and resistance. In doing so, the article argues that it is necessary to explore present and historical local understandings and conceptualisations of migration, in relation to solidarity practices, forced migration, migrant smuggling, imaginaries of mobility.

The collection of articles presented in this special issue sheds light on the social trajectories of youth migration from Eastern Africa to North Africa and Europe. It deals with studies from the Somali area, Eritrea and Ethiopia, following migrants’ paths along the routes of illegalised migration through Sudan, Libya and Tunisia, where cases from West Africa are also included, and further north to Italy and other European destinations.

The articles explore the lived experiences, immediate social networks, and infrastructures of mobility that frame migrants’ journeys, documenting migration paths along what official documents call the East African migration route. They build on scholarly literature such as Schapendonk and Ayalew, who explore mobility networks and infrastructures, as well as on research conducted on the East African/Libya route such as the work of Ayalew, Belloni and Treiber.Footnote1 But they also move beyond such dimensions, which revolve around the preoccupation of explaining how people move. In fact, they look at migration in a broader transformative sense: as a social force reshaping territories, groups, economic and political structures and, additionally, as a communal rather than an individual trajectory thereby foregrounding the relationship between mobility and social change.Footnote2

We use the concept of “social worlds” to grasp the set of realities produced by mobility and inhabited by people on the move, with their translocal and transnational connections, and by local communities (sedentary or equally mobile). The social worlds of Eastern African migrants represent a form of emerging connectivity of spaces, from local to regional and transcontinental levels, outlining new and specific histories of territories and people shaped by movement and its control. While other scholars such as Scheele, de Bruijn and van Dijk have explored regional connectivity in the context of the Sahelian belt and other African regions, we use it in the context of Eastern Africa and specifically link it to migration.Footnote3 Migrants interact with diverse social actors that perform, facilitate or control mobility: not only smugglers, traffickers and border guards, but a wider array of figures and relationships whose contours and historical genealogies will be reconstructed by the articles presented in this special issue. Increasingly interconnected regions, borders and borderlands, migration corridors and routes, refugee camps and detention centres, migratory “hubs” like city neighbourhoods or villages providing travel services – all represent spatial configurations emanating from these social dynamics. Moreover, the social worlds constructed through mobility intersect the macro-policies of migration management and control, which generate power configurations framed by (often diverging) European and African state interests. In a sort of counter-movement to population movements, migration policies initiated by European institutions have travelled south to the so-called countries of origin, thus further contributing to the reshaping of spaces and power relations. Based on these interrelations, we consider it essential to study Eastern African migration heading north by concurrently considering in-depth analyses of migration dynamics in Northern Africa, specifically Libya and Tunisia, and by examining the contents and effects of the EurAfrican border regimes.

Our central assumption is that the social worlds constructed by regional mobility represent crucial elements for understanding contemporary (Eastern) African societies and their political dynamics, in relation to the increased relevance of migration diplomacy, to the interconnectivity above mentioned, and to the transnational and diasporic spheres that lie at the core of the social and economic reproduction of states and societies in the Horn and more generally in Eastern Africa. We aim to highlight, through these interconnections, the genealogies and transformations of the systems of violence composing the reality of migration in the regions explored, but also the various and interrelated systems of solidarity which, although fragmented and even misused at times, sustain migrants’ trajectories, social projects and resistance.

Ultimately, the encounters explored in this special volume also include encounters between perspectives and disciplines, as the articles traverse African studies (with themes like youth and generations in Africa, the history of African borders, global networks and African societies)Footnote4 and migration and refugee studies (focusing on displacement and migration management, migration policies, African and European migratory regimes, local histories of displacement and humanitarianism).Footnote5 This intermingling is encouraged by recent research on the history of concepts and themes across disciplines, identifying common red threads that date back to colonial times and increasingly affect the postcolonial era. This includes, for example, the historical evolution of borders and population containment systems, workforce management, aid, brokers and intermediaries, state models of gatekeeping and extraversion.Footnote6

In the current discussion on the EurAfrican migration regimes, i.e. the rewriting of African borders and regions under the imperative of migration management led by the EU externalisation process, the articles fill a persisting gap by looking at the effects of these regimes in African societies, specifically in Eastern Africa.Footnote7 The following sections will start unpacking some of these issues, first by reflecting on the relationship between war, violence and mobility, and elaborating from this a temporal frame within which to place the different essays; then by highlighting the concept of migration diplomacy and showing the spatial configurations emerging from these interrelated dynamics; and finally, by addressing the relationship between migration and solidarity.

War diasporas and mixed migration

The forms of mobility analysed by the articles of this special issue can generally be described as directly or indirectly induced by or connected to war and/or political repression. In an immediate sense, population movements – for example in Somalia, resulting from the struggle between the Islamic courts movement and the Ethiopian army in Mogadishu in 2006, or in Eritrea, deriving from the 1998–2000 border war with Ethiopia – are linked to the displacements produced by the violence of armed conflicts. Confirming the “generative” nature of war, these two examples also represent, for Somalia and Eritrea, a turning point in the emergence of the new waves of youth migration extensively described by the articles. In other cases, population movements are linked to occasional returns of violence and armed clashes in a situation of protracted conflict, like in Somalia, but also to deep and persistent processes of dismembering of the social and economic fabric resulting from the same protracted condition. In Eritrea, in addition to recurrent tensions with Ethiopia, displacement is also linked to the authoritarian turn taken by its regime before the 1998 border war and accelerated with the war.Footnote8

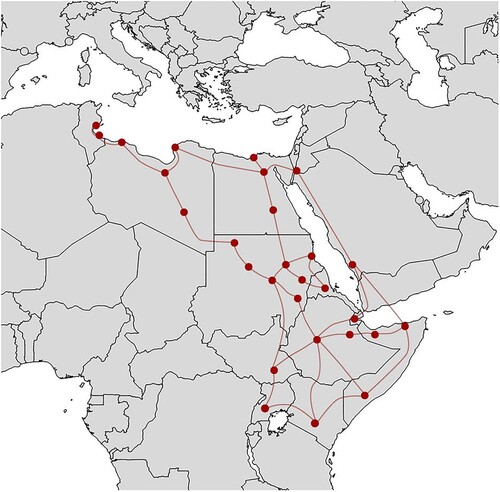

We must then look at the long-term transformations produced by war: the formation of historical diasporas due to recurring conflicts (which for both Eritrea and Somalia began well before the 1990s) and the growing relevance of these overseas communities in the reproduction of local societies. As these transnational networks consolidate, they generate a need for inclusion, which leads in turn to further mobility. In this aspect, protracted forced displacement and economic migration dynamics tend to coincide.Footnote9 In neighbouring countries and along the transit routes migrants on the move draw support from the communities of co-nationals residing there, as they constitute infrastructures providing shelter and resources, or from overseas connections. Regional mobilities (within the Horn of Africa and beyond – see ) and their spatial outcomes (refugee camps, city neighbourhoods inhabited by migrants in Nairobi, Addis Ababa, Kampala or Khartoum, and networks relating to business, religion or study) thus intersect and mutually support long-distance mobilities. In their movements, the migrants follow the paths already trodden by previous displacements, but they also nourish the transnational communities in numerical, economic or other terms, contributing to the constant remoulding of such diasporic worlds.Footnote10 Moreover, population movements shaped by war and by diasporic exchanges sustain relationships in which long-lasting bonds of mutual obligation and support between people, as well as long-lasting divisions and fragilities, are forged and reproduced, drawing on the dramatic experiences people have shared and through which they have been divided. In sum, today the Horn of Africa paradigmatically represents one of the areas in which a long-term and recurrent stratification of crises, conflicts and related mobility has emerged, generating complex configurations and circular effects. This systematic relationship between war and mobility represents a solid definition of forced migration in sociological terms, clearly different from the one deriving from legal frameworks, which we will explore in the next section.

In pointing out the multiple linkages between war and mobility, we must similarly include the transit points crossed by Eastern African migrants on their way to Europe, looking specifically at Libya and Tunisia. Here, since 2011 war and internal turmoil have redrawn the conditions of mobility in a migratory space that is constituted by a complex stratification of unpredictable dynamics. This space has emerged as (1) an area of destination linked to an oil-driven labour market (Libya) for increasingly internationalised groups of people, (2) a point of departure (especially Tunisia) for North African citizens’ migration to Europe and (3) a place of convergence and transit for migrants and asylum seekers from Western, Sahelian and Eastern Africa, as well as the Middle East, heading north across the Mediterranean.

As violence and exploitation in the Libyan migratory space have increased under the pressure of war, the articles show how mobility, and migrants’ physical bodies, have become a stake in the conflict. They also show how EU efforts to curb illegal migration on the one hand and to restore stability in Libya on the other, are not necessarily compatible and often contradict each another.Footnote11 In any case, the complex picture emerging from the intersection between migration and the war in Libya further blurs the abstract categories of destination, departure and transit. The term “mixed migration” comes closer to capturing the complex reality of the Libyan migratory space and the Mediterranean crossings, yet this term has been repeatedly politicised and thus charged with different ambiguous meanings.

Finally, discussing the relationship between mobility and conflict leads us to highlight three different temporalities that crosscut the articles presented here. First, there are the deep temporalities linked to the history of conflicts in the region, as they have been experienced by different generations of Somalis and Eritreans. The most significant points in time for Somali migration are the turn of the 1990s, with the beginning of the civil war, and later the 2005–2006 return of large-scale conflict with the intervention of the Ethiopian army in Mogadishu. In Eritrea, the early 1990s coincided with the declaration of independence and the slow return of the previously displaced Eritrean diasporas, while it was the 1998–2000 border war with Ethiopia that brought about the new wave of youth emigration.

Then, there is the temporality structuring the process of externalisation of the EU border, a topic we will expand on in the next section. Third, there is the temporality deriving from the destabilisation of North Africa, which has profoundly affected the latest generations of migrants in Libya: the beginning of the so-called Arab Spring in 2011, with the toppling of the Tunisian and Libyan regimes, the 2014 dramatic increase of disorder in Libya, the consequent reaction of the EU states attempting since 2015–2017 to re-establish control of irregular migration across the central Mediterranean in collaboration with new gatekeeping actors in Tunisia and Libya.

Focusing on case studies from between 2005 and 2020, the articles of this issue not only reconstruct what happened in those years but also envisage the subsequent transformations of the above-sketched migratory spaces. Specifically, they show how internal reasons and dynamics linked to Libya paved the way to the current emergence of Tunisia as relevant departure point for crossing the central Mediterranean, with the number of sea crossings rising significantly again in 2022–2023 since 2018.

Migration diplomacy

The relationship between mobility and war also has implications for the legal frameworks within which mobility occurs. People on the move due to the recurring forms of displacement described in the previous section, who are entitled to recognition as refugees, are in fact specifically targeted by containment policies, alongside other undesired mobilities from the global South towards the global North (typically youth migration from poor countries). Refugee camps are the official and primary structures of containment, but as displacement far exceeds the spatial and temporal limits of the camps, the irregularisation of the long-distance trajectories of asylum-seekers towards the North and, increasingly, of their regional movements, is used as political containment in current migration policies promoted by the global North and implemented with the necessary involvement of African states. The exclusion of potential refugees and of young migrants from poor areas from the international regimes of regular mobility, forcing them into irregular routes, creates what are generally termed “mixed migratory flows”. A large body of literature is devoted to these aspects, generally referred to, for the regions we are dealing with, as the externalisation of EU borders to Africa.Footnote12 The articles by Antonio Morone and Chiara Pagano in this issue, devoted to the migratory regimes in Libya and Tunisia, touch upon these elements with specific attention to African actors and histories.

The Mediterranean Sea is a crucial junction point of these trends. On its northern shore the Schengen area of free circulation consolidated in the 1990s totally reconfigured the mobility systems between Europe and the global South. On its southern shore states like Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Morocco have been induced to take a specific and ambiguous role in the externalisation of the EU border. For these states, mobility towards Europe has historically been crucial (as a population safety valve and a source of income) and border rigidification has been a real obstacle. Furthermore, since the 1990s, these countries have received an increasing number of people from sub-Saharan Africa. For Libya this has been due to the expanding oil-economy and late President Moammar Gaddafi’s African policy. Now these states are asked by European countries to prevent migrants from crossing the Mediterranean by any means.Footnote13 Readmission agreements and other forms of diplomatic engagement have become a central tool to achieve this goal. Despite their name focusing on the facilitation of readmitting national citizens when detected without permission in the Schengen space to the North African countries, the deals that have been signed throughout the 2000s and until today are much more complex: in exchange for preventing the departure of migrants from their territories, these countries were promised, and have received, economic and developmental resources and have been provided with tools to prevent migratory movements (training, equipment, legal transplants, funds, border co-surveillance, police and intelligence cooperation). In other cases, not economic but political stakes are involved, from international recognition to the implicit request of turning a blind eye to human rights or democracy standards.Footnote14

Overall, the continuous evolution and remoulding of migration control measures have constructed a southward-expanding EurAfrican border, in constant need (and search) of solid interlocutors within African governments. Through the so-called Khartoum process,Footnote15 this expansion has now reached the Eastern African and Horn of Africa states, palpably confirming how current political relationships between Africa and Europe are largely conditioned by migration policies and dynamics. This reveals much more complex implications than a simple unilinear expansion of the border from north to south. At the political level, it is evident that the process of production of a new EurAfrican border and consequent diplomatic relationships exceeds the limited scope of migration management and touches upon dynamics in which African states and their elites are engaged in reconfiguring their power. This, for instance, in terms of relationships between centres and margins, of autonomy and sovereignty vis-à-vis internal and international actors, and of leverage for claiming resources. At the social level, even more clearly, the new focus on border management reflects broader social changes and spatial transformations induced by regional conflicts and mobility.

Spaces of mobility and control

Through initiatives led by international organisations dealing with migration – such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) – and by the combined efforts of European and African states emphasising a “regional approach to migration”, a specific goal of the southward movement of the border is concerned with the identification and delimitation of migration corridors and routes. Knowledge production, soft diplomacy (i.e. common legal frameworks, research, institutionalisation of border posts, training of border guards), active surveillance and direct actions have been applied. The rare articles on the Eastern African corridors that started to appear in the 2000s – compared to the major attention paid to the West African routes via the Sahelian countries – were part and parcel of the increasing attention by international organisations, itself a factor in consolidating specific routes as well as institutional border policies.Footnote16

Migration routes or corridors are, however, much more complex spatial arrangements than described by diplomacy or media. What we call migratory corridors are exceptional phenomena of connectivity based on the integration of spaces, alignment of territories and regions, spatial density, unification of localities (towns, cities, hubs, border posts, etc.), all connected to specific historical circumstances and provisional combinations of factors.Footnote17 Being the outcome of cultural, economic and socio-political processes, migratory spaces reflect the interplay of multifaceted dynamics. The development of migration routes is influenced by EurAfrican border policies and acquires within this system particular and recurrent dynamics: a progressive increase in migrant numbers, widespread visibility, congestion, repression and subsequent detours to other routes. However, they also depend on the evolutions and innovations of the systems and networks presiding over migrant movements, ranging from mere facilitators to smugglers and traffickers, and on the escalation of autonomous economic stakes related to those networks.Footnote18

Indeed, the category of transit countries or migration corridors just hints at a more general space of mobility and control that is defined by the combined actions of migrants’ mobilities, their facilitators and exploiters’ strategies and the EurAfrican diplomacy of border surveillance and migration containment. This migratory space, which unifies Horn and Mediterranean mobility regimes, constitutes one of the vectors of the internationalisation of societies in the Horn of Africa, defining on the one side their transnational character and, on the other, the emergent field of migration diplomacy, which, as mentioned, has captured more and more of African states’ foreign policies. The migratory space also has historical depth, as it has been crossed and interconnected by several contacts and relationships at different levels (for instance, the historical role of Egypt and Sudan in the Horn, the colonial linkages and mobilities connecting Libya to the Horn and the refugee communities residing along the migration routes).Footnote19 But the current changes are more closely linked to the transformative force of recent migration, connecting places and generating social worlds.

This space is certainly a space of violence, a condition further aggravated since the descent of Libya into civil war. For many people on the move along these routes, brutality, violence and death are part of the everyday challenges they constantly encounter. After the Libya war, migration trajectories for young Africans crossing the country to reach Europe, have witnessed an increase of systematic exploitation and cruelty, with dramatic consequences not only for the people involved but also for their family groups, both in the regions of origin and in the diaspora. As a result, such migration trajectories have been increasingly disrupted. Eastern Africans displaced by war and prosecution, or by poverty and the search for a better life, may end up finding themselves in worse situations than the ones they left behind, as they are incarcerated, tortured, raped, sold or in the worst case, killed, in countries like Libya and on their way to Europe.Footnote20

The emerging regional spaces described in this collection are analysed by highlighting the web of interrelations involving humanitarian actors, border control agencies, migrants as well as the networks of support/smuggling/trafficking they are immersed in. The articles of this issue further illustrate how core concepts within the field of migration and forced migration studies (i.e. the categories of smuggling and trafficking, of forced and voluntary migration, transit migration and mixed migration flows) are challenged by the complexities of the African mobility regimes.Footnote21 In essence, none of the social trajectories of migrants crossing the social worlds illustrated in the articles falls within the clear definition of these categories. Indeed, all of them cross, reassemble and overlap them. Furthermore, the typology of coercion and violence (including imprisonment, ransoms, extortion) does not completely coincide with the two categories of smuggling or trafficking of migrants, posing various problems also in terms of legal recognition and in terms of international protection, being exercised on people outside their home country.Footnote22 By analysing migrants’ solidarities, their social worlds and their struggles for inclusion, this special issue takes an ethnographically informed and diachronic perspective to shed light on the collective dimension of migration and its relevance for the societies of origin. This perspective takes into account how migrants’ mobility relates to group formation and dynamics of inclusion and exclusion within the home communities and the transnational Horn of Africa societies.

Ambiguous solidarity

Building on the complex spatial arrangements that migrants move through, we find it essential to explore the networks and practices of solidarity that migrants from the Horn of Africa depend on before, during and after migration. Throughout this special issue, the articles pose questions centred around the forms of solidarities that occur in the social worlds of East African migrants: how is solidarity defined and how is it practiced in the different social spaces within the migratory route(s) from the South to the North? Which factors enable or prevent solidarities, group formation, belonging or, in contrast, isolation and loss? And to what extent, if at all, do young migrants achieve personal safety, security, autonomy, resources, connections or status through such solidarity practices?

To answer these questions, this special issue draws on the vast body of literature that has focused on solidarity practices in migration contexts. Going back to the Manchester school of thought, we draw on studies of mutual aid and support practices within African societies. Following researchers of the Manchester school including Gluckman, Mitchell and Little,Footnote23 we explore migration from the vantage point of migrants’ motivations for movement, which often lie in socio-economic obligations to their social surroundings. Aid and social support play a very important role in the social world of migrants before, during and after migration,Footnote24 especially in traditional integrated systems of solidarity where kin and relatives make up their socio-economic security system.Footnote25 In this issue, we also explore new solidarity practices that arise due to various forms of social organisation during migration – a sort of “community-making across diverse spatial fields”.Footnote26 These new networks of solidarity can be fruitful during migration in that new acquaintances and their knowledge can provide the migrant with new ways of moving forward, yet in other instances, they can halt those same motivations and opportunities of physical and social mobility.

Several researchers have analysed the notion of solidarity in migration, and moved beyond the original rural-urban migration context of the Manchester School. Scholars such as Sanchez, de Leon and Vogt, in the context of Mexico and USA, have examined the political and social infrastructures that migrants attempting to cross the Mexican-American border face and are a part of.Footnote27 Others have focused on European responses to the so-called migration crisis, either exploring civil society’s responses to (inter)national policies on refugees or suggesting new policies that are more inclusive. Augustin and Jørgensen explored how the solidarity movement, understood as members of civil society, has been very visible and active in showing solidarity with refugees. The authors explored three different types of solidarity: autonomous, civic and institutional through fieldwork among volunteers in Greece, Denmark and Spain. They approached solidarity as “generative and inventive” and show how civil society provides alternatives to the nationalist policies of the European nation-states.Footnote28 In his research on the development of diversity and transitions in civil society movements working in migration contexts, Oikonomakis explored solidarity with a focus on Southern European civil society during the so-called migration crisis.Footnote29 With a similar focus, Zamponi described a shift in civil society from direct practices of solidarity with migrants to practices of mobilisation for political demonstrations and civil disobedience.Footnote30

Where the above-mentioned scholars explored solidarity from a civil society perspective, van Hear and Cohen suggested an alternative model to previous global responses to displacement based on migrants’ current practices in the world. Their approach emphasised solidarity as generative and inclusive, as it seeks to find long-term solutions for people displaced in the world.Footnote31 Zhang, Sanchez and Achilli also sought to provide an alternative to the current political climate, as they dismantled the political portrait of the migrant smuggler as the root cause of irregular migration through their extensive ethnographic work among facilitators of migration.Footnote32 De Leon’s book did the same as it explored survival and hope in the world of human smuggling.Footnote33

Thus, solidarity migration networks consist of a wide variety of actors, such as European civil society organisations and relatives or co-nationals along the migration route. Building on this insight, the collection of articles in this volume seeks to broaden the notion and scope of solidarity to explore relations among, between and across the social networks of African migrants. Studying solidarity in displacement and migration requires distancing from its classical notion, in which solidarity is at the same time the web of mutual obligations that keep societies together and the values emanating from these forms of collaboration/obligation. In migration, such bonds are posed under stress, often weakened or dismantled, sometimes even correspond to the reason why people flee. As such, they need to be reconfigured mobilising heterogeneous ties, values, resources, alliances. We place these reconfigurations at the core of our analyses. Furthermore, we suggest that it is necessary to explore present and historical local understandings and conceptualisations of migration, in this case from the Horn of Africa, including themes such as forced migration and migrant smuggling. We zoom in on the local views of migration by taking emic notions of migration practices to the forefront of our contributions.

The articles of Ciabarri, Simonsen and Tarabi, Vitturini and Dirie in this volume contribute important insights to the literature on solidarity, as they explore the social worlds of Somali migrants through the emic notion of tahriib. Tahriib is an Arabic term that has migrated to the Somali language in the 1970s and today refers to undocumented migration, mostly conducted by young Somalis.Footnote34 Ciabarri traces the genealogy of tahriib and the transformations of its use and meaning among Somalis. By exploring the shifts in meaning since 2005, he portrays how such transformations reflect an increasingly restrictive regulation of international migration and how that shapes perceptions and practices of tahriib over time, highlighting a lack of solidarity from the broader global society.Footnote35

Building on the latest understanding of tahriib as undocumented migration towards Europe, Simonsen and Tarabi explore how recent migration trends among the Somali youth and the rise of the migrant smuggling network, known in Somali as Magafe, have challenged traditional practices of solidarity and rendered them increasingly ambiguous. Somali notions of solidarity have historically been a mechanism of care within the clan system, committing members of the clan to take care of each other in times of need. In this article, the authors argue that traditional practices of solidarity are challenged through the intensification of ransom collection in the Somali community.Footnote36

Vitturini, in his article, unfolds the complexity of the ambiguous network of solidarity within Somali communities during tahriib, as he follows Somali migrants and their encounters with other Somalis along the migration route. His article points to the fact that Somali migrants actively disconnect and reconnect with transnational solidarity networks as such networks bring about a mix of help and exploitation. He also argues that tahriib, in this sense, becomes a form of revolt against or liberation from constraints of kinship or cultural stigmas (specifically the belonging to the Gaboye caste groups) as well as a means of evading more traditional forms of solidarity.Footnote37

In his article, Dirie takes as his starting point the notion of evading solidarity towards the nation-state when young Somalis do tahriib. His article gives an intimate look into the local political, social and cultural responses to what Dirie frames as “the tahriib movement”.Footnote38 His article argues that Somaliland migrants in the tahriib movement have been perceived as unpatriotic, having left the national homeland for foreign ones and having taken foreign social and cultural practices in place of their own. Somalilanders inside and outside Somaliland perceive the tahriib movement as directly opposing their narratives of nation-state building and ideals of nationalism. Consequently, young migrants are often ostracised and shunned in political and social spheres in Somaliland, which has led to intriguing cultural, social and political responses to the tahriib movement.

Taken together, by exploring the emic notion of tahriib in various ways, the four articles illustrate the importance of investigating solidarity through the transformative and shifting social surroundings of migrants, as this reveals how solidarity can be generative and inclusive, but also violent and exclusive. Similarly, Pagano and Morone’s articles on Tunisia and Libya urge us to take a closer look at the often-contradictory notions of solidarity, as various stakeholders in the migration sector challenge migrants’ perceptions and practices of solidarity as they seek to organise solidarity networks away from their country of origin.

In her article, Pagano takes her point of departure in the post-2011 Tunisia turmoil, exploring how southeastern Tunisia has turned into a humanitarian borderscape. She shows how the personnel of international organisations and their partner NGOs, who have been entrusted with the assistance and protection of mobile populations, including those from the Horn of Africa, have contributed to border enforcement. By drawing on fieldwork among Tunisian NGOs, national and international activists, refugees, asylum seekers and irregularised migrants, she explores how this process has impacted spontaneous solidarity networks among migrants that emerged post-2011. She does so by exploring stakeholders’ definitions of solidarity through hierarchies of deservingness.Footnote39

Morone also explores the limits of institutional solidarity, as he talks about “cycles of containment” in the context of increasing instability in Libya after 2014 due to the civil war.Footnote40 By comparing and discussing migrants’ life stories collected in Tripolitania and Southern Tunisia, the article explores migrants’ solidarity-based strategies to deal with traps of containment, networks of (im)mobility and varying relations with host communities.

Emphasising contradictory perceptions and practices, Hung and Fusari explore a dissonance between European and Eritrean understandings of solidarity in migratory contexts. Fusari, in her article on the transnational mobility of migrants from the Horn of Africa, explores practices of solidarity through an ethnography of survivors-at-home. By taking as her point of departure the tragic sinking of a boat carrying Eritreans from Libya to Italy on 3 October 2013 in Lampedusa, she examines the post-tragedy solidarities emerging at local, national and international levels, shedding light on the survivors-at-home’s right to know. Bringing various contexts and emic notions of solidarity together, she explores to what extent the dissonance between European and Eritrean understandings of migratory contexts and practices regarding deceased migrants can lead to the formation of solidarity within the Eritrean diaspora.Footnote41

Finally, Hung explores the emic concept of agaish, a Tigrinya word that translates somewhere between the meaning of guest and relative. The point of departure is the Processo Agaish trial, where Italian prosecutors accused Eritrean refugees of human trafficking and of exploiting “their clients” desires to move further north. Hung shows how the translation of agaish was part of the legal defence's strategy to show that the purported trafficking victims of the case were not “clients”, but “guests”, agaish, often family members of the accused, who hosted them, not for money but for something akin to hospitality. Thus, her article explores the contradictory uses of solidarity and the negative effects such contradictions can have on migrant movements.Footnote42

Bringing these various social and geographical spaces and emic notions of solidarity together, the articles elucidate how migrants cope with increasing levels of violence and dispossession, and how challenges and ambiguities imposed on emic notions of solidarity cause different kinds of solidarities to emerge and transform within the social worlds of volatile migrant populations.

Conclusion

Exploring fragments of solidarities on the move mobilised by African migrants heading north – in a migratory space marked by increasing violence, exploitation and insecurity – means shedding light on migrants’ struggles to build and maintain social ties, shape their life worlds and be included into transnational spheres and spaces where protection and support is provided. On the one hand, this analysis leads to reconstructing the genealogies and conditions of increased violence and exploitation along the route to Libya and Europe, which compel to revisit consolidated analytical categories central to current representations of these phenomena: those of smuggling and trafficking, of forced and voluntary migration, of what a “transit” or a “journey” is, and of migrants’ agency in highly risky settings and social isolation. On the other hand, by focusing on the nexus between migration and solidarity, we highlight from an ethnographically informed and diachronic perspective, how the latter does not exclusively refer to actions of support and aid provided by activists or institutions in Africa and Europe. The concept also sheds light on the mutual aid provided by migrants, by their families, friends, and social connections, in a struggle to reproduce social groups and in contrast with the systems of containment and exploitation encountered along the way. Such dispersed ties, real or just envisaged, sustain and nourish the various forms of social imagination accompanying and guiding the migrants en route.

By conceiving solidarity in connection to the migrants’ social worlds, we also address mobility from a transformative perspective, pointing out emerging forms of connectivity across spaces and social groups as well as emerging power relations. Building on this framework, it is possible to explore topics related to agency and diaspora formation, to emerging transnational societies deriving from protracted crises and conflict induced mobility as well as from recent socio-economic breakdowns and political crises. We thus interrogate migration as a form of social change linked to specific modes of reproduction and crisis of the societies of origin and investigate the social, rather than individual, dimension of migrants’ agency. Furthermore, we explore how social ties are imbued with uncertainty, suspicion, and how they shift between trust and mistrust, and can in some cases lead to exploitation and abuse. The dimensions of solidarity in migrants’ journeys, nourishing and guiding their trajectories, are as pivotal as the experiences of solitude, abandonment and loss, and deeply intertwine with them.

Acknowledgements

This article is the result of a joint effort and discussions. The introduction and the first three sections were written by Luca Ciabarri, the fourth section and the conclusions by Anja Simonsen. We would like to thank the editors of the Journal of Eastern African Studies and the reviewers who have read through our entire special issue. We are grateful for their dedication and important comments made towards this special issue. We would also like to thank the group of eminent scholars contributing to this publication. Each article provides an intimate look into the social worlds of migrant journeys.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Schapendonk, “What if Networks Move?” and “Navigating the Migration Industry”; Ayalew, “Precarious Mobility” and “Refugee Protections”; Belloni, The Big Gamble; Massa, “Borders and Boundaries”; and Treiber, “Entangled Paths.”

2 Castles, “Understanding Global Migration”; and Cornelissen, “Migration as Reterritorialization.”

3 Scheele, Smugglers and Saints of the Sahara; Brachet, Migrations transsahariennes; van Dijk, Foeken, and de Bruijn, Mobile Africa; and de Bruijn and van Dijk, The Social Life.

4 Christiansen and Vigh, Navigating Youth; Graw and Schielke, The Global Horizon; Honwana and De Boeck, Makers and Breakers; Nugent and Asiwaju, African Boundaries; Engel, Boeckler, and Müller-Mahn, Spatial Practices; Gallien and Weigand, Smuggling; and Kleist and Abdi, Global Connections.

5 Hyndman, Managing Displacement; Hyndman and Giles, Refugees in Extended Exile; and Gaibazzi, Dunnwald and Bellagamba, EurAfrican Borders.

6 Brankamp and Daley, “Laborers, Migrants, Refugees”; Cooper, Africa since 1940; and Bayart and Ellis, “Africa in the World.”

7 Gaibazzi, Dunnwald and Bellagamba, EurAfrican Borders; and Triulzi and McKenzie, Long Journeys.

8 Keating and Waldman, War and Peace in Somalia; Negash and Tronvoll, Brothers at War; and Hyndman and Giles, Refugees in Extended Exile.

9 Massey, “Social Structure.”

10 Kleistand Abdi, Global Connections; Ciabarri, “Assemblages of Mobility and Violence”; and Simonsen and Tarabi, “Images of Torture.”

11 Morone, “The Cycle of Migrants’ Containment”; and Pagano, “Inhabiting Humanitarian Borderscapes.”

12 Andersson, Illegality Inc.; Gaibazzi, Dunnwald, and Bellagamba, EurAfrican Borders.

13 Paoletti, The Migration of Power.

14 Cassarino, Unbalanced Reciprocities; Cassarino, “A Reappraisal.”

15 Morone, “The Cycle of Migrants’ Containment”; Stern, “The Khartoum Process”; Otte and Babokar, “Migration Control à la Khartoum.”

16 ICMPD, The East African Migration Route; and Hamood, African Transit Migration.

17 Ciabarri, “Dynamics and Representations.”

18 Ibid.

19 Chelati Dirar et al., Colonia e postcolonia.

20 The analysis of this evolution along the East African migration route is the main purpose of the articles in this collection.

21 Kuschminder and Triandafyllidou, “Smuggling, Trafficking, and Extortion.”

22 Ciabarri, “Assemblages of Mobility and Violence”; Morone, “The Cycle of Migrants’ Containment”; Pagano, “Inhabiting Humanitarian Borderscapes”; Fusari, “Survivors-at-Home”; Hung, “Amongst agaish.”

23 Little, “The Role of Voluntary Associations,” 580.

24 Simonsen, Tahriib – Journeys into the Unknown.

25 Ibid.

26 Silverstein, Postcolonial France, 32.

27 De Leon, The Land of Open Graves; Sanchez, Human Smuggling and Border Crossing; amd Vogt, Lives in Transit.

28 Augustin and Jørgensen, “Solidarity and the ‘Refugee Crisis’.”

29 Oikonomakis, “Solidarity in Transition,” 65–98.

30 Zamponi, “From Border to Border,” 99–123.

31 Van Hear and Cohen, “Refugia: A New Transnational Polity.”

32 Zhang et al. “Crimes of Solidarity,” 6–15.

33 De Leon, Soldiers and Kings.

34 Simonsen, Tahriib – Journeys into the Unknown.

35 Ciabarri, “Assemblages of Mobility and Violence.”

36 Simonsen and Tarabi, “Images of Torture.”

37 Vitturini, “Solidarities on the Move.”

38 Dirie, “Social, Cultural and Political Responses,” XX.

39 Pagano, “Inhabiting Humanitarian Borderscapes.”

40 Morone, “The Cycle of Migrants’ Containment.”

41 Fusari, “Survivors-at-Home.”

42 Hung, “Amongst agaish.”

Bibliography

- Andersson, Ruben. Illegality, Inc. Oakland: University of California Press, 2014.

- Augustin, Oscar Garcia, and Martin Bak Jørgensen. Solidarity and the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Europe. Cham: Springer, 2018.

- Ayalew, Tekalign. “Refugee Protections from Below: Smuggling in the Eritrea-Ethiopia Context.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 676, no. 1 (2018): 57–76.

- Ayalew, Tekalign. “Precarious Mobility: Infrastructures of Eritrean Migration Through the Sudan and the Sahara Desert.” African Human Mobility Review 5, no. 1 (2019): 1482–1509.

- Bayart, Jean-François, and Stephen Ellis. “Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion.” African Affairs 99, no. 395 (2000): 217–267.

- Belloni, Milena. The Big Gamble. The Migration of Eritreans to Europe. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019.

- Brachet, Julien. Migrations transsahariennes. Vers un désert cosmopolite et morcelé (Niger). Paris: Éditions du Croquant, 2009.

- Brankamp, Hanno, and Patricia Daley. “Laborers, Migrants, Refugees: Managing Belonging, Bodies, and Mobility in (Post)Colonial Kenya and Tanzania.” Migration and Society 3, no. 1 (2020): 113–129.

- Cassarino, Jean-Pierre, ed. Unbalanced Reciprocities: Cooperation on Readmission in the Euro-Mediterranean Area. Washington, DC: Middle East Institute, 2010.

- Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. “A Reappraisal of the EU’s Expanding Readmission System.” The International Spectator 49, no. 4 (2014): 130–145.

- Castles, Stephan. “Understanding Global Migration: A Social Transformation Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36, no. 10 (2010): 1565–1586.

- Chelati Dirar, U., S. Palma, A. Triulzi, and A. Volterra, eds. Colonia e postcolonia come spazi diasporici. Attraversamenti di memorie, identità e confini nel Corno d'Africa. Roma: Carocci Editore, 2011.

- Christiansen, C., M. Utas, and H. E. Vigh, eds. Navigating Youth, Generating Adulthood. Social Becoming in an African Context. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2006.

- Ciabarri, Luca. “Dynamics and Representations of Migration Corridors: The Rise and Fall of the Libya-Lampedusa Route and Forms of Mobility from the Horn of Africa (2000–2009).” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 13, no. 2 (2014): 246–262.

- Ciabarri, Luca. “Assemblages of Mobility and Violence: The Shifting Social Worlds of Somali Youth Migration and the Meanings of Tahriib, 2005–2020.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 58–77. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2333071.

- Cooper, Frederick. Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Cornelissen, Scarlett. “Migration as Reterritorialization: Migrant Movement, Sovereignty and Authority in Contemporary Southern Africa.” In African Alternatives, edited by Leo de Haan, Ulf Engel, and Patrick Chabal, 119–143. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- de Bruijn, Miriam, and Rijk van Dijk, eds. The Social Life of Connectivity in Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- De Leon, Jason. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Sonoran Desert Migrant Trail. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015.

- De Leon, Jason. Soldiers and Kings: Survival and Hope in the World of Human Smuggling. New York: Viking Press, 2024.

- Dirie, Ja’afar. “Social, Cultural and Political Responses to Somaliland’s Tahriib Movement.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 78–96. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2348913.

- Engel, Ulf, Marc Boeckler, and Detlef Müller-Mahn. Spatial Practices Territory, Border and Infrastructure in Africa. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

- Fusari, Valentina. “Survivors-at-Home and the Right to Know: Solidarities in Eritrea in the Aftermath of the Lampedusa Tragedy.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 135–154. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2333652.

- Gaibazzi, Paolo, Stephen Dunnwald, and Alice Bellagamba, eds. EurAfrican Borders and Migration Management. Political Cultures, Contested Spaces, and Ordinary Lives. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Gallien, Max, and Florian Weigand. The Routledge Handbook of Smuggling. Abingdon: Routledge, 2022.

- Graw, K., and S. Schielke, eds. The Global Horizon: Expectations of Migration in Africa and the Middle East. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2012.

- Hamood, Sara. African Transit Migration Through Libya to Europe: The Human Cost. Cairo: The American University in Cairo, 2006.

- Honwana, A., and F. De Boeck, eds. Makers and Breakers: Children and Youth in Postcolonial Africa. Oxford: James Currey Press, 2005.

- Hyndman, J. Managing Displacement: Refugees and the Politics of Humanitarianism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

- Hyndman, J., and W. Giles. Refugees in Extended Exile: Living on the Edge. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Hung, Carla. “Amongst Agaish: The Criminalization of Eritrean Migrants’ Communities of Care.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 155–173. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2350731.

- International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). The East Africa Migration Routes Report. Vienna, September 2007.

- Keating, M., and M. Waldman, eds. War and Peace in Somalia: National Grievances, Local Conflict and Al-Shabaab. London: Hurst, 2018.

- Kleist, N., with Masud Abdi. Global Connections. Somali Diaspora Practices and Their Effects. Research Report. Nairobi: Rift Valley Institute, 2022.

- Kuschminder, Katie, and Anna Triandafyllidou. “Smuggling, Trafficking, and Extortion: New Conceptual and Policy Challenges on the Libyan Route to Europe.” Antipode 52 (2020): 206–226.

- Little, Kenneth L. “The Role of Voluntary Associations in West African Urbanization.” American Anthropologist 59 (1957): 579–596.

- Massa, Aurora. “Borders and Boundaries as Resources for Mobility. Multiple Regimes of Mobility and Incoherent Trajectories on the Ethiopian-Eritrean Border.” Geoforum 116 (2020): 262–271.

- Massey, Douglas S. “Social Structure, Household Strategies, and the Cumulative Causation of Migration.” Population Index 56 (1990): 3–26.

- Morone, Antonio M. “The Cycle of Migrants’ Containment Between Libya and Africa: Navigating Their Life among Dreams, Resilience, and Defeats.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 18–35. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2332828.

- Negash, Tekeste, and Kjetil Tronvoll. Brothers at War. Making Sense of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War. Oxford/Athens: James Currey/Ohio University Press, 2000.

- Nugent, P., and A. I. Asiwaju, eds. African Boundaries: Barriers, Conduits and Opportunities. London: Cassell/Pinter, 1996.

- Oikonomakis, Leonidas. “Solidarity in Transition: The Case of Greece.” In Solidarity Mobilizations in the “Refugee Crisis”, edited by Donatella della Porta, 65–98. Cham: Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology, 2018.

- Oette, Lutz, and Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker. “Migration Control à la Khartoum: Eu External Engagement and Human Rights Protection in the Horn of Africa.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 36, no. 4 (December 2017): 64–89. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdx013.

- Pagano, Chiara. “Inhabiting Humanitarian Borderscapes: Claiming Rights and Organizing Dissent in Post-2011 Southeastern Tunisia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 36–57. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2332042.

- Paoletti, Emanuela. The Migration of Power and North-South Inequalities. The Case of Italy and Libya. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Sanchez, Gabriella E. Human Smuggling and Border Crossings. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Schapendonk, J. “What if Networks Move? Dynamic Social Networking in the Context of African Migration to Europe.” Population, Space and Place 21, no. 8 (2015): 809–819.

- Schapendonk, Joris. “Navigating the Migration Industry: Migrants Moving Through an African-European Web of Facilitation/Control.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44, no. 4 (2018): 663–679.

- Scheele, Judith. Smugglers and Saints of the Sahara: Regional Connectivity in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Silverstein, Paul A. Postcolonial France. Race, Islam and the Future of the Republic. London: Pluto Press, 2018.

- Simonsen, Anja. Tahriib – Journey’s Into the Unknown. An Ethnography of Uncertainty in Migration. Cham: Palgrave Macmillian, 2023.

- Simonsen, Anja, and Mohamed S. Tarabi. “Images of Torture: ‘affective Solidarity’ and the Search for Ransom in the Global Somali Community.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 117–134. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2332041.

- Stern, Maximilian. “The Khartoum Process: Critical Assessment and Policy Recommendations.” IAI Working Papers 15–49. Rome, December 2015.

- Treiber, Magnus. “Entangled Paths Through Different Times. Refugees in and from the African Horn.” Africa Today 69, no. 1–2 (2022): 62–87.

- Triulzi, A., and R. McKenzie. Long Journeys. African Migrants on the Road. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- van Dijk, Rijk, Dick Foeken, and Mirjam de Bruijn. Mobile Africa. Changing Patterns of Movement in Africa and Beyond. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

- Van Hear, Nicholas, and Robin Cohen. “Refugia: A New Transnational Polity in the Making.” https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/project/the-refugia-project.

- Vitturini, Elia. “Solidarities on the Move Between the Horn of Africa and Italy: Somali Migrants’ Disconnection and Networking Practices in the 2010s.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 18, no. 1 (2024): 97–116. doi:10.1080/17531055.2024.2332827.

- Vogt, Wendy. Lives in Transit: Violence and Intimacy on the Migrant Journey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018.

- Zamponi, Lorenzo. “From Border to Border: Refugee Solidarity Activism in Italy Across Space, Time and Practices.” In Solidarity Mobilizations in the “Refugee Crisis”, edited by Donatella della Porta, 99–123. Cham: Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology, 2018.

- Zhang, Sheldon X., Gabriella E. Sanchez, and Luigi Achilli. “Crimes of Solidarity in Mobility: Alternative Views on Migrant Smuggling.” ANNALS, AAPSS 676, no. 1 (2018): 6–15.