ABSTRACT

Background

The effect of interventions based on the creative arts for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events was estimated for measures of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other psychological symptoms.

Method

Using a pre-registered protocol, relevant journal articles were identified through searches of: PsycInfo; Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection; CINAHL and PsycArticles. Data were pooled using a random effects model, and effect estimates were reported as Hedges’ g.

Results

Pooled effect estimates indicated that arts-based interventions significantly reduced PTSD symptom scores compared to pre-intervention (15 studies, g = −.67, p < .001) and a control group (7 studies, g = -.50, p < .001). Significant reductions were also found for measures of negative mood, but results were mixed for externalizing problems and anxiety.

Conclusions

Despite variations in study quality, intervention approaches and types of trauma experience, the results tentatively suggest that creative arts-based interventions may be effective in reducing symptoms of trauma and negative mood.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Exposure to traumatic events during childhood and adolescence is widespread, with prevalence estimates over 50% in Switzerland and the US (Smith et al., Citation2019), and likely higher in countries experiencing conflict or disaster. The consequences of traumatic experiences during childhood and adolescence do not only have a potentially negative impact on the child in the short term; they can have a long-term effect because of the social, emotional and psychological changes taking place as children grow and develop (Dye, Citation2018). This review aims to examine the evidence for interventions based on the creative arts in the alleviation of psychological distress following exposure to traumatic events. In order to do this, it is necessary to make some assumptions about what constitutes a traumatic event or experience.

One way in which potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence are conceptualised is within diagnostic criteria for trauma-related disorders. For adolescents and children over 6 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) defines a traumatic event (Criterion A) to be “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” that has occurred in at least one of the following ways: ‘directly experiencing the traumatic event(s); witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others; or, learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. In cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must have been violent or accidental’. A further criterion relating to “experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s)” is unlikely to apply to many children and adolescents, as it is limited specifically to work-related exposure such as those experienced by emergency service responders rather than exposures such as online or in the media.

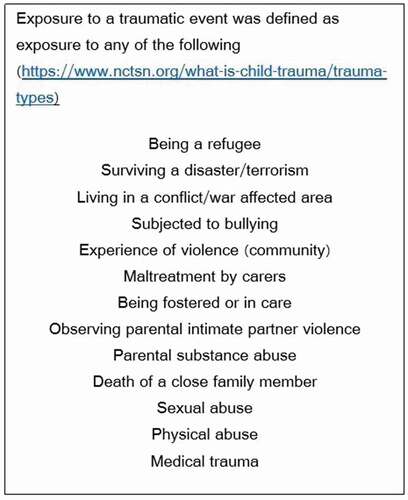

Since its introduction in 2013, many have argued that DSM-5 Criterion A provides an overly restrictive definition of potentially traumatic events. For example, Hyland et al. (Citation2021) found that neglect, emotional abuse, and bullying in childhood were as strongly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as events conforming to the Criterion A definition, with the consequence that strict adherence to Criterion A would miss a substantial proportion of PTSD cases. They argue instead for the DSM to provide guidelines on what constitutes a traumatic event to help the clinician to decide, which is the approach used in the International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11) conceptualisation (World Health Organization, Citation2018). A further complication in defining traumatic events for children occurs because, depending on their stage of development and their attachment relationships, a child might experience a particular event or experience as traumatic even if that event might seem insignificant from the point of view of an adult (Van Westrhenen & Fritz, Citation2014). These factors make it challenging to define potentially traumatic events for a review such as this but, after much consideration, we judged that the types of experiences outlined by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network () encompassed Criterion A but also include other potentially trauma-inducing experiences in children and adolescents. We therefore chose these categories of experience to define exposure to potentially traumatic experiences in this study.

Psychological interventions based on art, music, drama, dance/movement or poetry are referred to as creative arts-based interventions because of their roots in the arts (Malchiodi, Citation2015). There are specific forms of therapy developed around each of these, but also broader types of interventions (for example, community psychosocial programs) which incorporate components based on one or more of the creative arts. Creative arts-based interventions are part of a wider group of expressive interventions that includes bibliography, journalling and sandplay but in order to avoid too broad a focus this review was restricted to creative arts-based interventions.

Understanding the mechanisms by which creative arts-based interventions might be effective in treating children and adolescents exposed to trauma is still in its infancy. There is now widespread agreement that trauma experiences are both psychological and physiological (Malchiodi, Citation2015; Van der Kolk, Citation2014). Memories of traumatic events may not be available in the form of explicit (or conscious) memory but are instead stored “implicitly” or in “sensory memory” making it difficult to verbally describe the traumatic event (Malchiodi, Citation2015; Van der Kolk, Citation2014). Where this is the case, expression through art, music or movement can be a way to convey ideas without words, allowing externalization of trauma memories and also a sense of containment and control over them (Malchiodi, Citation2015). Creative arts-based interventions also generally require the child or adolescent to be active and it is argued that this activity taps into the sensory memory of the event and may help bridge implicit and explicit memories (Malchiodi, Citation2015). Creative arts-based interventions provide a way of working with socially and culturally diverse groups as they can transcend language barriers and may draw on historical art forms (Van Westrhenen & Fritz, Citation2014). This can be a particular advantage in many of the contexts in which interventions to alleviate the effects of exposure to traumatic events are implemented, such as among refugee groups in the West or in deprived or ethnically diverse areas. The nonverbal expression facilitated by creative arts-based interventions also means the approach can be used whatever the stage of verbal development of the child. These advantages likely explain why interventions based on the creative arts are being used internationally in a variety of contexts to treat children and adolescents who have been exposed to a variety of potentially traumatic events. However, approaches based primarily on the creative arts are not currently recommended by national bodies (such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK) due to the lack of evidence for their effectiveness.

Previous overviews of the literature (Eaton et al., Citation2007; Van Westrhenen & Fritz, Citation2014) found such a scarcity of good quality empirical evidence on the effectiveness of creative arts-based interventions for children and adolescents exposed to trauma, that their reviews focused mainly on documenting any existing case studies, qualitative studies or intervention studies. They concluded that the effectiveness of creative arts-based interventions for treating symptoms of trauma in children and adolescents could not be determined at that time because of this lack of evidence. However, since these reviews, the body of evidence in this area has grown, so the aims of the present review were therefore 1) to systematically assemble quantitative results from this growing evidence base and 2) calculate overall intervention effect estimates. Common psychological consequences of exposure to traumatic events or experiences include PTSD, externalizing problems (disruptive behavioural problems directed towards the environment), internalizing problems (emotional problems directed towards inner experience such as depression and anxiety), and negative effects on self-esteem, positive affect and adaptive behaviours (Wethington et al., Citation2008). The review and meta-analysis described here therefore examined intervention effects for each of these symptom groups separately.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42020158258). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards (Moher et al., Citation2009) were followed.

Criteria for inclusion/exclusion

Population

The age-range for inclusion in the review was children or adolescents up to the age of 18 years old. shows that for a study to be eligible for inclusion, all participants had to have been exposed to one or more traumatic events as set out in . If children or adolescents in these categories made up only a subgroup of the sample, the study was not included unless subgroup statistics were available. For example, samples of refugees and immigrants were only included if subgroup statistics were available for the refugees, as being an immigrant was not one of our criteria. Studies were also eligible for inclusion if exposure to a traumatic event was not specified but all those in the sample met the threshold for mild, moderate or severe PTSD pre-intervention according to scores on a PTSD symptom measure. Similarly, studies were eligible if they reported that all those in the sample had been diagnosed with PTSD by a clinician pre-intervention.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for population.

Interventions

For studies to be eligible for inclusion the intervention had to either be a purely creative arts intervention or a multi-component intervention that included a substantial creative arts aspect or component. As mentioned in the introduction creative arts-based interventions are defined as those involving painting or drawing, pottery, sculpture, music, drama, dance, clowning, poetry or any mix of these. The intervention could involve either active participation in creating art (for example, performing a drama) or as an audience for the arts (for example, watching a performance). Eligible interventions could be implemented at the individual level (for example, individual art therapy), group level (group drumming) or classroom level and in any type of setting. The intervention had to involve the child/adolescent rather than, for example, their parent(s). Interventions classed as expressive but not creative (for example, sand play, journalling or bibliotherapy) were not included unless they also included a substantial creative arts component. Studies of interventions to reduce the likelihood of an experience being traumatic (for example, playing music during medical procedures) were not eligible for inclusion.

Comparator(s)/control

Studies with a waitlist control, treatment as usual or an active control were included. Studies with no control group were also included.

Outcomes

Studies with any quantitative measure of PTSD/trauma symptoms, externalising problems (disruptive behavioural problems directed towards the environment and others), internalising problems (subdivided into negative mood, anxiety and other problems directed towards inner experience), self-concept, positive affect or adaptive behaviours (including interpersonal skills) were eligible for inclusion. A secondary outcome measure was ability to express/articulate the trauma. Measures could be self-completed or completed by parents, teachers or clinicians. However, to be eligible for inclusion in the review the outcome(s) had to relate to the children/adolescents who participated in the intervention rather than, for example, relating to parental distress or well-being.

In order to be included in the meta-analysis studies needed to include sample sizes, means and standard deviations (or other types of statistics) for outcomes, allowing between-group or pre- to post-intervention standardised effect sizes to be calculated.

Study design(s)

Eligible designs included randomised controlled trials, controlled trials and pre- versus post-intervention studies. Such studies were eligible even if described as a pilot study. Articles describing case-studies were included if outcomes were measured quantitatively and the number of participants was at least three (as this allowed the necessary statistics for the meta-analysis to be calculated). Crossover studies were also eligible for inclusion in which case data from the first phase only were included as this equates to a controlled trial.

Type of article

Peer-reviewed studies published in scientific journals written in English or with an English translation were eligible for inclusion.

Information sources

Search strategy. Studies were identified by searching the following databases: PsycInfo; Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection; CINAHL and PsycArticles with no limits on date. The exact search terms are presented in the pre-registered protocol but were made up of the following four sets of terms: children and adolescents (child* OR adolescen* OR school* etc.) AND trauma or traumatic event (traum* OR ptsd OR refugee OR asylum OR war OR conflict, etc.) AND creative arts-based intervention (arts OR paint OR “creative expression” OR music OR drumming OR singing, etc.) AND type of study (evaluat* OR “outcome of” OR trial OR effectiveness, etc.). In addition, reference lists of included studies and other relevant reviews were hand searched to identify additional potentially eligible studies.

Study selection

The search strategy was developed by LS and LM and was implemented by LS in February 2020. Titles and abstracts were downloaded into a reference management database (www.Mendeley.com) where duplicates were removed. Initially, title and article types were reviewed by LM to remove obviously irrelevant articles, articles not in the English language (or with no English translation), and items other than journal articles. Abstracts of the remaining articles were reviewed by LM excluding any that obviously did not meet the exclusion criteria. Full texts of articles were obtained for abstracts which appeared to meet the inclusion criteria or did not contain enough information to assess inclusion. After assessing the full-text LM divided the papers into those that were obvious for inclusion and those that were obvious for exclusion. The remaining papers were classified in discussions between all co-authors.

Data extraction (selection and coding)

A standardised data extraction spreadsheet was developed and tested by LM and LS and then data from the eligible studies was extracted by LM. Where required data was missing LM made at least one attempt to contact the corresponding author to request the necessary data.

Data items

For each journal article, the first author and date were extracted along with the country in which the study took place. The creative arts-based intervention was coded as either being solely an arts intervention or a component of a larger intervention and the number of sessions making up the intervention were extracted where available. Mean age and the percentage of females in the study were extracted or calculated. Studies were categorised according to whether PTSD was “diagnosed” in all those in the sample pre-intervention or not. “Diagnosed” here meant meeting a minimum score for mild, moderate or severe PTSD using a PTSD measure or otherwise diagnosed by a clinician. The type of study design was categorised as “between groups” for controlled trials and “within group” for studies which compared measures pre- versus post-intervention. Type of comparison group was extracted for between-group designs. For each outcome measure, the name of the measure was extracted and categorised as either a measure of trauma symptoms, externalising problems, negative mood, anxiety, other internalising problems, positive self-concept, positive affect or adaptive behaviours. For each outcome measure the number of participants, mean and standard deviation were extracted (or calculated from available data) pre- and post-intervention for the intervention group and, for between-group designs, the comparison group.

Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment: Within Studies

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers (Kmet et al., Citation2004). Where a study included qualitative or survey components as well as a quantitative evaluation of an intervention, only the latter was focused on for the scoring. The Standard Quality Assessment is composed of 14 criteria but two of these: blinding of investigators and blinding of participants as to the intervention, were not included in the quality assessment as these criteria are not generally met in creative arts-based intervention studies. The remaining 12 criteria relate to: study objectives; study design; subject selection; subject characteristics; random allocation of treatments; outcomes; sample size; analysis; estimates of variance; confounding; sufficient detail in results; and conclusions. Each of the criteria are scored 2 if met, 1 if partially met and 0 if not met. The total across the 12 criteria is divided by the maximum possible score to obtain a number between 0 and 1 (with 1 indicating perfect quality). Following detailed discussions between LS, LM and SJS regarding the coding for six studies, SJS then coded the quality for all 41 studies. Eleven (27%) of the studies were subsequently selected randomly for independent coding by LM. Agreement between raters was assessed by calculating the intraclass correlation (ICC) using a two-way random-effects model for absolute agreement. This gave an ICC of 0.84.

Meta-Analytic Strategy

Stata Version 16 (StataCorp, Citation2020) was used to conduct meta-analysis (metan command) and meta-regression (metareg command) using the macros described in Palmer and Sterne (Citation2016). The effectiveness of creative arts-based interventions was assessed for each category of outcome in two ways a) a between-groups analysis aggregating data for creative arts-based interventions compared with controls and b) a within-group analysis aggregating data for pre-intervention compared with post-intervention. All but one of the studies included in the between-groups analysis had pre-intervention data that allowed the intervention arm from such studies to be included in the within-group analysis as well.

For each category of outcome, a summary effect size (Hedges’ g) was calculated using a random effects model to allow for heterogeneity of treatment effects across studies (Riley et al., Citation2011). Effect sizes between .2 and .49 were categorised as small; between .5 and .79 as medium; and .80 or greater as large (Cohen, Citation1977). For comparison of creative arts-based interventions with a control group (between groups design), the means and standard deviations post-intervention or other statistics allowing calculation of the effect size were used. For cross-over designs, data for the first period where the creative arts-based intervention and control were compared was used for a between groups comparison. If a study included more than one creative arts-based intervention (for example, Brillantes-Evangelista, Citation2013) or more than one population (for example, Poznysh et al., Citation2019), standardised effect sizes were calculated for each intervention or for each population separately. For within-group comparisons, pre- and post-intervention means and standard deviations were used to calculate the effect size as recommended by Lipsey and Wilson (Citation2001) or else effect size was calculated using available statistics. In the case where the within-group standard deviation needed to be estimated from the standard deviation of differences, a correlation coefficient of .5 between the pre- and post-interventions scores was assumed. For both the between- and within-groups analyses, relatively few studies included follow-up data, and if they did there was a wide range of follow-up durations. Therefore, for consistency, analysis was restricted to the closest measure following the intervention.

For all analyses, heterogeneity of effect sizes was estimated using the Q-statistic and I2 values. The Q-statistic tests the hypothesis that variance of the effect sizes is no different than would be expected as a result of sampling error alone. I2 indicates the proportion of heterogeneity among the studies that is beyond that which may be expected by chance.

Meta-regression was then used to examine whether any of the heterogeneity in effect sizes between studies was explained by study characteristics. Meta-regression was restricted to outcomes where there were a minimum of 8 studies as recommended by Jenkins and Quintana-Ascencio (Citation2020). Further, in order to minimise the degrees of freedom used by the covariate, levels of potential categorical moderators were collapsed down to two. This resulted in consideration of three potential moderators a) the number of sessions of intervention, b) whether the intervention was purely creative arts-based or whether the creative arts-based intervention was a component of a broader intervention, and c) whether the trauma symptom scores in the study sample all met a minimum threshold for PTSD or not. Potential moderators were examined individually as the number of studies was not large enough to examine the joint effect of the potential moderators together.

Risk of Bias Across Studies

Publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots and Egger’s test for small sample effects (Egger et al., Citation1997). In addition, sensitivity analysis was performed whereby each study was omitted in turn and the impact on the outcome inspected (Stata command metainf). Studies were categorised as having excessive influence if their omission changed the p-value for the overall effect from significant (p < .05) to nonsignificant (p > .05) or vice versa or if the point estimate for the overall effect omitting that study fell outside the 95% confidence interval for the original overall effect. If a study was found to exert excessive influence, results were presented with and without that study, alongside discussion of whether the study had any very different characteristics to the others that might explain its influence. Finally, meta-regression was used to examine whether the quality assessment score explained any variation in effect sizes between studies.

Results

Study Selection

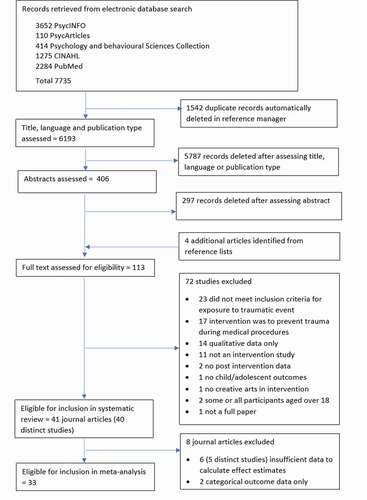

The search identified 7,735 potentially relevant journal articles which reduced to 6,193 after duplicates were removed. After reviewing titles, language and publication type, 406 articles remained for abstract review, of which 113 were selected for full-text review. Forty-one of these met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review but two of these related to the same study so 40 distinct studies were included. Of these 33 met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis (see ).

Summary of Study Characteristics

Study characteristics for each of the 40 studies included in the systematic review are shown in . The table shows that 24 interventions consisted of arts-based therapy with 14 conducting art therapy, 7 music therapy, 2 dance or movement, and one a poetry intervention. The sixteen other studies conducted mixed interventions that included a substantial creative arts-based component. Three of these were community-based psychosocial interventions whilst the remaining studies mainly combined an creative arts-based intervention with some other form of therapy such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) or individual or group psychotherapy. In addition to variability in the type of intervention, there was also substantial variation in the number of sessions making up the intervention, ranging from a single session (three studies) up to 30 sessions.

Table 2. Summary of study characteristics.

Seventeen studies were controlled trials with additional between-group comparisons available from two crossover studies and one Solomon 4-groups design. Three studies (Brillantes-Evangelista, Citation2013; Decosimo et al., Citation2019; Hill & Lineweaver, Citation2016) compared more than one creative arts-based intervention with a control group and one study (Poznysh et al., Citation2019) examined the same intervention in two different populations. For eight studies the comparison group was a control group, for 5 a waitlist control group (WLC) and for five studies treatment or life as usual (TAU or LAU). One study used jigsaw puzzles as the comparison and one used a mixed intervention excluding the creative arts-based intervention of interest (music therapy). The other 20 studies utilised a single group pre-post comparison design.

There were 2,534 children and adolescents across the 40 studies with sample sizes ranging from 3 to 403. One study included only males and five only females but the other studies were mixed. Mean ages ranged from 8.0 to 16.3 years. Participants in all studies had suffered one or more of the experiences with the potential to induce trauma symptoms listed in . The most common category was being a refugee (nine studies) for which exposure to multiple types of potentially traumatic events is likely. Sexual abuse (six studies) or sexual and physical abuse (three studies) was the next most common type of potentially traumatic experience. shows that all the experiences listed in were included with many children and adolescents experiencing more than one. In four studies participants’ symptom scores all met the minimum threshold for diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Seventeen studies were conducted in North America, eight in South East Asia, six in Africa and three in each of Australia and the Middle East. One study was conducted in India, one in Norway, and one in Ukraine.

Most studies included more than one outcome measure meeting the inclusion criteria (see ). The primary outcomes measured were combined into categories with trauma symptom scores, externalising behaviours and symptoms of negative mood each being measured in 17 studies. Fifteen studies included a measure of anxiety; nine of adaptive behaviours and the remaining outcome categories were measured in seven or fewer studies. Measures of a secondary outcome, ability of the child/adolescent to express themselves about the traumatic experience, were included in two studies. Most studies used measures that are well-validated and reliable utilizing self-report or reports of parents, teachers or clinicians. However, three studies (Ager et al., Citation2011; Leung et al., Citation2018; Lev-Wiesel & Liraz, Citation2007) designed measures specifically for use in their study.

Risk of Bias Within Studies

Scores of study quality ranged from 0.45 to 0.92 (). Studies excluded from the meta-analysis did not present the statistics needed to calculate an effect estimate and thus tended to score lower. Studies that were predominantly qualitative also tended to score lower because the scoring was based on the quantitative component of the study which was usually described in less detail.

Meta-analysis of Impact of Creative Arts-based Interventions

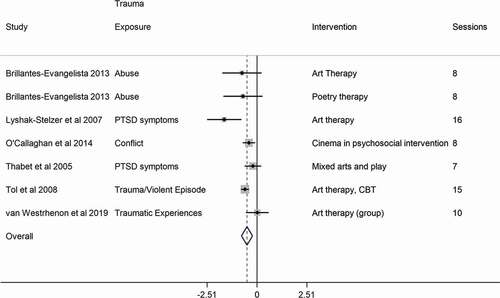

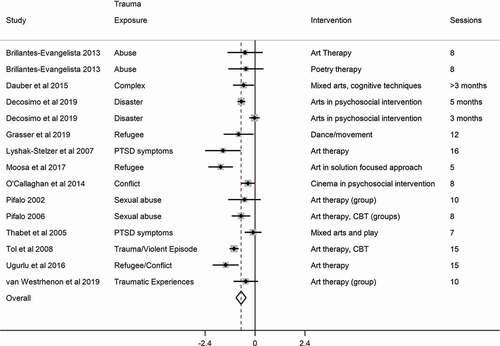

shows pooled effect sizes from the meta-analysis reported as Hedges’ g, for the impact of the creative arts-based interventions on the different categories of outcomes. A negative effect size indicates a reduction in the intervention group compared to the comparison group for the between-group designs and a reduction in post-intervention compared to pre-intervention for the within-group designs.

Table 3. Combined effect estimates (Hedges’ g) for each outcome category.

Trauma symptom scores: Seven studies included PTSD symptom scores in a between-group study design and 15 studies included PTSD symptom scores in a pre- vs post-intervention study design. The pooled standardised effect sizes in show an overall significant decrease in PTSD symptom scores with a medium effect size for the between groups analysis (g = −.50, p < .001) and for the within group analysis (g = −.67, p < .001).

also shows significant heterogeneity between the studies included in the meta-analysis for trauma symptom scores; this is illustrated in the Forest Plots in for the between and within groups meta-analyses, respectively. Meta-regression showed that neither the number of sessions nor whether the study sample all had pre-intervention trauma symptom scores that met the minimum threshold for a diagnosis of PTSD explained a significant amount of this heterogeneity (see supplementary information for more detail). Meta-regression suggested that reduction in trauma symptom scores may be greater in studies that were solely art-based compared to those where it was a component (p = .078 for the within group analysis). The effect size (g) for interventions that were solely creative arts-based was −.93 (95% CI −1.32 to −.54) for the within group analysis, whereas for the mixed interventions it was −.48 (95% CI −.78 to −.43).

Externalising problems: For those studies that included a measure of externalizing problems the within group analysis showed significant reductions following intervention (14 studies, g = −.51, p < .001) but the between-group analysis did not (7 studies, g = −.13, p = .283). None of the moderators explained a significant amount of the variation in effects sizes.

Negative mood: The meta-analysis showed significant reductions in measures of negative mood for both the between and within group analysis (9 studies, g = −.38, p = .006 for the between-group analysis; 14 studies, g = −.49, p < .001 for the within group analysis). The effect sizes were smaller than those found for trauma symptom scores.

Anxiety: For studies which included a measure of anxiety, the within-group analysis showed significant reductions (12 studies, g = −.68, p < .001 anxiety) but the between-group analysis did not (4 studies, g = −.22, p = .237 anxiety). None of the moderators explained a significant amount of the heterogeneity of effect sizes.

Other internalizing problems: The number of studies that included measures of other internalizing problems was small (three for the between groups analysis and seven for the within groups analysis). No significant effect was seen for the between-group analysis (g = −.11, p = .131) but a significant reduction post-intervention was found for the within groups analysis (g = −.37, p = .001). There was no significant heterogeneity between studies and the number of studies was too small to investigate moderation.

Self-concept: Measures of self-concept were included in only two studies with between-group comparisons and four with within-group comparisons. However, results suggested that measures of self-concept had increased post-intervention (g = .42, p = .002) and increased compared to a control group (g = .49, p = .056). There were too few studies to examine moderation.

Positive affect: The number of studies including measures of positive affect was small (three for the between groups analysis and four for the between-group analysis). There was no clear evidence of a clear intervention effect (g = .22, p = .074 for the between groups analysis; g = .49, p = .127 for the within groups analysis). There were too few studies to examine moderation.

Adaptive behaviours; Three studies included measures of adaptive behaviour for the between groups analysis and 9 for the within groups analysis. The overall effect size from the between groups analysis was negative indicating a decline but it was not significant (g = −.22, p = .383). The effect size for the within-group analysis was positive suggesting an improvement in adaptive behaviours (g = .29, p = .054) pre- to post-intervention. No moderators explained a significant amount of the heterogeneity.

Ability to express trauma: For the secondary outcome of being able to talk about or articulate the traumatic experience, there was only one study and this showed an increase in the intervention group compared to a control group (g = .80, p = .003).

Bias Across Studies

Funnel plots and results from Egger’s test suggested no significant publication bias apart from for the within group comparison for positive self-concept. For this comparison, the intercept of .93 (p = .017) suggested that larger studies had larger effect sizes. The sensitivity analysis indicated no studies with undue influence. Conducting a meta-regression with study quality as a potential moderator provided no evidence that study effect sizes were related to study quality apart from the within group analysis for externalising problems. For this comparison, poorer quality studies had larger effect sizes (p = .013). Details of the results for examining bias across studies can be found in the supplemental information.

Discussion

Previous reviews have emphasised the lack of empirical evidence to assess the effectiveness of creative arts-based interventions for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events (Eaton et al., Citation2007; Van Westrhenen & Fritz, Citation2014). However, since those reviews, further studies have been conducted and this review and meta-analysis is a first tentative attempt to combine the quantitative results to date to get an overall picture. We included studies of children and adolescents who had experienced a broad but well-defined range of traumatic experiences in studies which used creative arts as a substantive component of their intervention. We examined the impact of these interventions on trauma symptom scores and measures of other common consequences of exposure to traumatic events. The number of studies is still relatively low, especially for controlled trials, and the quality of studies is variable. However, the available evidence suggests that creative arts-based interventions reduce trauma symptom scores with a medium effect size and measures of negative mood with a small effect size. For the other common psychological consequences of exposure to traumatic events (externalising problems, anxiety, other internalising problems, self-concept, positive affect, adaptive behaviours and ability to articulate the traumatic event) the results were more mixed with pre-post within group comparisons showing greater beneficial effects than between-group analyses of data from controlled trials.

Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) is currently the UK nationally recommended intervention for treating trauma symptoms in children and adolescents with Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) considered if there is a lack of engagement or response to TF-CBT (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2018). A recent meta-analysis of 21 TF-CBT and 9 EMDR studies of young people (average age 12) who had experienced a traumatic event showed a reduction in trauma symptoms with an effect size (g) of −.359 (95% CI −.631 to −.87) (Lewey et al., Citation2018). In their analysis, Lewey et al. (Citation2018) combined between and within group designs, while we conducted separate analysis for each but our findings of g = .-.50 (95% CI −.78 to −.23) for the between groups analysis and −.67 (95% CI −.91 to −.43) for the within group analysis overlaps with theirs suggesting a comparable effect.

Adaptations can be made to TF-CBT to include creative arts activities (and/or play) depending on the young person’s age and abilities. However, even with this level of flexibility in the implementation of TF-CBT, the manualised approaches of TF-CBT and EMDR are more homogeneous than the interventions included in this review. These varied greatly in the type of creative art, the type of practitioner, the age of the young people, the number of sessions and the setting or context (clinic, community, classroom, refugee camps in areas affected by conflict, etc.). Ideally, effect sizes would be disaggregated by these characteristics rather than combined over such a variety of interventions but the number of studies available at present did not permit this. The interventions here also varied in terms of whether they were solely arts-based or arts in combination with other forms of intervention, and this was considered as a potential moderator. Meta regression found greater reduction in trauma symptom scores for solely creative arts-based interventions compared with mixed interventions although this was not statistically significant. If it indicates a real difference, one possible explanation is that practitioners of art, music, dance or poetry therapy are likely to be qualified therapists specialising in their area of the arts whereas arts components in combination studies are more likely to be implemented by other types of practitioners. Additionally, many of the studies that implemented arts-based approaches within a broader intervention were large community programmes conducted in challenging settings, which may have limited the effect of the intervention.

This study examined the effect of arts-based interventions in children and adolescents exposed to traumatic experiences as opposed to restricting to studies where symptoms reached a threshold for PTSD to be diagnosed (of which there were only 4 in this review). This is in line with previous reviews of creative arts-based and other types of interventions (Lewey et al., Citation2018; Van Westrhenen & Fritz, Citation2014; Wethington et al., Citation2008). While we specified the criteria used to define a potentially traumatic event (see ) we included studies whether or not the aim of the study was to examine the effect on trauma symptom scores. Around half of the studies included in this review focused on the alleviation of trauma symptoms and this is reflected in the number of studies with trauma symptom scores as outcomes in the meta-analysis. However, the other half were focused on other outcomes such as alleviation of behavioural problems or depression or increasing positive self-concept. The aim of including these studies was to examine the effect of creative arts-based interventions on other common psychological consequences of exposure to traumatic events (Dye, Citation2018; Wethington et al., Citation2008). Vibhakar et al. (Citation2019) argue that depression is a common response in trauma-exposed children that merits more serious consideration. The results of both the between and within groups meta-analyses suggested a beneficial effect of creative arts-based interventions on negative mood with a small effect size. This could be due to the more general benefits of creative arts-based interventions, which give pleasure through making, doing and inventing, and enhancing self-worth through self-expression (Malchiodi, Citation2015). The few studies included in this review which examined self-concept did also find a positive effect. For the other outcomes, the results were mixed with the within-group analysis suggesting a stronger beneficial effect than the between-group analysis. This was particularly so for externalising problems and symptoms of anxiety. One possible explanation for this is that within-group changes are inflated because symptoms of exposure to traumatic events may change over time for reasons other than the intervention (for example, anxiety symptoms may reduce over time due to being in a safer environment). More controlled trials are needed to clarify the effect of creative arts-based intervention on these outcomes.

In addition to heterogeneity in the type of trauma experience and type of creative arts-based intervention, there was also considerable variation in the age of the young people both within and between studies. Turner et al. (Citation2020) found that the impact of adverse events is influenced by developmental stage. For example, they found that being taken away from the family was a stronger predictor of trauma symptoms in younger children (age 2–9) than in older children (age 10 − 17). Conversely having someone close commit suicide was both more common and a stronger predictor of trauma symptoms in older children (age 10–17) than younger children. The wide range of ages within many of the studies in this review precluded categorisation into a factor that could be included in the analysis as a potential moderator. Therefore, the heterogeneity of ages of the young people in this review will have introduced heterogeneity in the impact of particular types of traumatic experiences as well as likely heterogeneity in response to the intervention. Further research on how age and developmental stage fit into the picture for different intervention approaches and different types of trauma exposure is therefore warranted.

Limitations

Our inclusion and exclusion criteria allowed for considerable heterogeneity in intervention types, practitioners, outcome focus, and the contexts/setting of the study. There was also considerable heterogeneity in the type of traumatic experiences and gender and age of the children and adolescents. Combining across such different studies was done as a first step in examining the overall effect of creative arts-based interventions for different symptom categories, but this heterogeneity means the results need to be interpreted with caution. However, despite the heterogeneity in studies, a sensitivity analysis showed that excluding any one of the studies from any of the analyses did not significantly affect the results. The low number of studies also resulted in very limited exploration of moderators such as type of intervention, type of trauma exposure and number of sessions. As the number of good quality studies increases in the area, future meta-analyses can be more focused and examine moderation more precisely.

Classification of a creative art-based intervention for inclusion in the review was clear cut for many of the studies but less so where arts were a component of a broader intervention. Although these decisions were made in discussion with all co-authors, there is still a level of subjectivity such that others might make a different judgment. A more general limitation of the review is that most of the assessment of papers for inclusion and extraction of data was done by one author. However, a proportion of papers was independently double-coded for quality and any areas of uncertainty regarding study inclusion, data extraction, quality assessment were extensively discussed between co-authors.

The quality of studies included in the review varied greatly but we did not exclude studies on the basis of quality. One explanation for many of the lower quality scores was that we included detailed case studies if they had more than three participants and quantitative data available to enable calculation of the necessary means and standard deviations. We did this to maximise the evidence available, but such studies were not designed to meet the quality criteria for quantitative intervention trials. However, even in a substantial proportion of larger studies, data extraction was hampered by limitations in the presentation of relevant statistics. To examine the influence of quality and study size on the results we included the quality score as a moderator and conducted a test for small sample effects, but these indicated little impact on the meta-analysis results.

The restriction of studies to those published in peer-reviewed journals in English or with English translation will have missed studies published elsewhere which might have influenced the findings.

Conclusion

Previous reviews in this area concluded that there was insufficient evidence to make inferences about the effect of creative arts-based interventions. Now that more studies have been published in the field, this is a first tentative attempt to combine quantitative results on the effect of creative arts-based interventions to get an overall picture. The number of studies is relatively low, especially for controlled trials, and the quality of studies is variable, but our results suggest that creative arts-based interventions reduce trauma symptom scores with a medium effect size and measures of negative mood with a small effect size. For the other common psychological consequences of exposure to traumatic events (externalising problems, anxiety, other internalising problems, self-concept, positive affect, adaptive behaviours and ability to articulate the traumatic event) the results were more mixed. More trials of creative arts-based interventions compared with controls and with other intervention approaches are needed to examine whether these initial tentative findings are confirmed and to establish in what contexts the different approaches are most effective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ager, A., Akesson, B., Stark, L., Flouri, E., Okot, B., McCollister, F., & Boothby, N. (2011). The impact of the school‐based Psychosocial Structured Activities (PSSA) program on conflict‐affected children in northern Uganda. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(11), 1124–1133. h ttps://d oi.org/doi:1 0.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02407.x

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Baker, F., & Jones, C. (2006). The effect of music therapy services on classroom behaviours of newly arrived refugee students in Australia–A pilot study. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 11(4), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750601022170

- Bittman, B., Dickson, L., & Coddington, K. (2009). Creative musical expression as a catalyst for quality-of-life improvement in inner-city adolescents placed in a court-referred residential treatment program. Advances in Mind-body Medicine. United States, 24(1), 8–19.

- Brillantes-Evangelista, G. (2013). An evaluation of visual arts and poetry as therapeutic interventions with abused adolescents. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.11.005

- Chapman, L., Morabito, D., Ladakakos, C., Schreier, H., & Knudson, M. (2001). The effectiveness of art therapy interventions in reducing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in pediatric trauma patients. Art Therapy, 18(2), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2001.10129750

- Clendenon-Wallen, J. (1991). The use of music therapy to influence the self-confidence and self-esteem of adolescents who are sexually abused. Music Therapy Perspectives, 9(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/9.1.73

- Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

- Daigle, M. S., & Labelle, R. J. (2012). Pilot evaluation of a group therapy program for children bereaved by suicide. Crisis. Canada, 33(6), 350–357. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000147

- Dauber, S., Lotsos, K., & Pulido, M. L. (2015). Treatment of complex trauma on the front lines: A preliminary look at child outcomes in an agency sample. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(6), 529–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0393-5

- Decosimo, C. A., Hanson, J., Quinn, M., Badu, P., & Smith, E. G. (2019). Playing to live: Outcome evaluation of a community-based psychosocial expressive arts program for children during the Liberian Ebola epidemic. Global Mental Health, 6, e3. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2019.1

- Dye, H. (2018). The impact and long-term effects of childhood trauma. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(3), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1435328

- Eaton, L. G., Doherty, K. L., & Widrick, R. M. (2007). A review of research and methods used to establish art therapy as an effective treatment method for traumatized children. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34(3), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2007.03.001

- Egger, M., Smith, D. G., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- Ernst, A. A., Weiss, S. J., Enright-Smith, S., & Hansen, J. P. (2008). Positive outcomes from an immediate and ongoing intervention for child witnesses of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 26(4), 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.06.018

- Grasser, L. R., Al-Saghir, H., Wanna, C., Spinei, J., & Javanbakht, A. (2019). Moving through the trauma: dance/movement therapy as a somatic-based intervention for addressing trauma and stress among Syrian Refugee Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(11), 1124–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.07.007

- Hill, K. E., & Lineweaver, T. T. (2016). Improving the short-term affect of grieving children through art. Art Therapy, 33(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1166414

- Hilliard, R. E. (2001). The effects of music therapy-based bereavement groups on mood and behavior of grieving children: A pilot study. Journal of Music Therapy, 38(4), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/38.4.291

- Hilliard, R. E. (2007). The effects of Orff-based music therapy and social work groups on childhood grief symptoms and behaviors. Journal of Music Therapy, 44(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/44.2.123

- Ho, R. T. H. (2017). A strength-based arts and play support program for young survivors in post-quake China: Effects on self-efficacy, peer support, and anxiety. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(6), 805–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431615624563

- Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., McElroy, E., Ben-Ezra, M., Cloitre, M., & Brewin, C. R. (2021). Does requiring trauma exposure affect rates of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD? Implications for DSM-5. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 13(2), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000908

- Jenkins, D. G., & Quintana-Ascencio, P. F. (2020). A solution to minimum sample size for regressions. PLoS One, 15(2), e0229345. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229345

- Johnston, J. C., Healey, K. N., & Tracey-Magid, D. (1985). Drama and interpersonal problem solving: A dynamic interplay for adolescent groups. Child Care Quarterly, 14(4), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01113438

- Kang, H. J. (2017). Supportive music and imagery with sandplay for child witnesses of domestic violence: A pilot study report. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 53, 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.01.009

- Kim, J. (2015). Music therapy with children who have been exposed to ongoing child abuse and poverty: A pilot study. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 24(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2013.872696

- Kim, J. (2017). Effects of community-based group music therapy for children exposed to ongoing child maltreatment and poverty in South Korea: A block randomized controlled trial. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.01.001

- Kmet, L., M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L., S. (2004) Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields, HTA Initiative # 13, Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, downloaded 20/ 11/20 from https://www.ihe.ca/publications/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields

- Kruczek, T., & Vitanza, S. (1999). Treatment effects with an adolescent abuse survivor’s group. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23(5), 477–485. h ttps://d oi.org/doi:1 0.1016/S0145-2134(99)00023-X.

- Leung, H., Shek, D. T. L., Yu, L., Wu, F. K. Y., Law, M. Y. M., Chan, E. M. L., & Lo, C. K. M. (2018). Evaluation of “Colorful Life”: A multi-addiction expressive arts intervention program for adolescents of addicted parents and parents with addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(6), 1343–1356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9899-3

- Lev-Wiesel, R., & Liraz, R. (2007). Drawings vs. narratives: Drawing as a tool to encourage verbalization in children whose fathers are drug abusers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104507071056

- Lewey, J. H., Smith, C. L., Burcham, B., Saunders, N. L., Elfallal, D., & O’Toole, S. K. (2018). Comparing the Effectiveness of EMDR and TF-CBT for children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(4), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-018-0212-1

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical Meta-analysis. Sage.

- Lyshak-Stelzer, F., Singer, P., Patricia, S. J., & Chemtob, C. M. (2007). Art therapy for adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A pilot study. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 24(4), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2007.10129474

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2015). Neurobiology, creative interventions, and childhood trauma. In C. A. Malchiodi (Ed.), Creative arts and play therapy. Creative interventions with traumatized children (pp. 3–23). The Guilford Press.

- Meyer Demott, M. A., Jakobsen, M., Wentzel‐Larsen, T., & Heir, T. (2017). A controlled early group intervention study for unaccompanied minors: Can Expressive Arts alleviate symptoms of trauma and enhance life satisfaction? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58(6), 510–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12395

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine, 6((7)), e1000097.

- Momartin, S., Coello, M., Pittaway, E., Downham, R., & Aroche, J. (2019). Capoeira Angola: An alternative intervention program for traumatized adolescent refugees from war-torn countries. Torture: Quarterly Journal on Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and Prevention of Torture, 29(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.7146/torture.v29i1.112897

- Moosa, A., Koorankot, J., & Nigesh, K. (2017). Solution focused art therapy among refugee children. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 8(8), 811–816.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Post-traumatic stress disorder [ NICE Guideline No. 116]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

- O’Callaghan, P., Branham, L., Shannon, C., Betancourt, T. S., Dempster, M., & McMullen, J. (2014). A pilot study of a family focused, psychosocial intervention with war-exposed youth at risk of attack and abduction in north-eastern Democratic Republic Of Congo. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(7), 1197–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.004

- Palmer, T. M., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2016). Meta-Analysis in Stata: An updated collection from the stata journal (2nd ed.). Texas: Stata Press.

- Pifalo, T. (2002). Pulling out the thorns: Art therapy with sexually abused children and adolescents. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 19(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2002.10129724

- Pifalo, T. (2006). Art therapy with sexually abused children and adolescents: Extended research study. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 23(4), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2006.10129337

- Poznysh, V. A., Vdovenko, V. Y., Kolpakov, I. E., & Stepanova, E. I. (2019). Application of art therapy for correction of personal disorders of psychoemotional state of children – Inhabitants of radiation polluted territories and children displaced from the armed conflict on the Southern East of Ukraine. Problemy Radiatsiinoi Medytsyny Ta Radiobiolohii, 24, 439–448. https://doi.org/10.33145/2304-8336-2019-24-439-448

- Pretorius, G., & Pfeifer, N. (2010). Group art therapy with sexually abused girls. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631004000107

- Quinlan, R., Schweitzer, R. D., Khawaja, N., & Griffin, J. (2016). Evaluation of a school-based creative arts therapy program for adolescents from refugee backgrounds. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 47, 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2015.09.006

- Riley, R. D., Higgins, J. P. T., & Deeks, J. J. (2011). Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 342, d549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d549

- Rowe, C., Watson-Ormond, R., English, L., Rubesin, H., Marshall, A., Linton, C., Amolegbe, A., Agnew-Brune, C., & Eng, E. (2017). Evaluating art therapy to heal the effects of trauma among refugee youth: The Burma Art Therapy Program evaluation. Health Promotion Practice, 18(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839915626413

- Schreier, H., Ladakakos, C., Morabito, D., Chapman, L., & Knudson, M. M. (2005). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after mild to moderate pediatric trauma: A longitudinal examination of symptom prevalence, correlates, and parent-child symptom reporting. The Journal of Trauma, 58(2), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000152537.15672.b7

- Smith, P., Dalgleish, T., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2019). Practitioner review: posttraumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(5), 500–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12983

- StataCorp. (2020). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16.

- Tepper-Lewis, C. (2019). Description and evaluation of a dance/movement therapy programme with incarcerated adolescent males. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 14(3), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2019.1631885

- Thabet, A. A., Vostanis, P., & Karim, K. (2005). Group crisis intervention for children during ongoing war conflict. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 14(5), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-005-0466-7

- Tol, W. A., Komproe, I. H., Susanty, D., Jordans, M. J. D., Macy, R. D., & De Jong, J. T. V. M. (2008). School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in indonesia: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA, 300(6), 655–662. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.6.655

- Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., & Henly, M. (2020). Strengthening the predictive power of screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in younger and older children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104522

- Ugurlu, N., Akca, L., & Acarturk, C. (2016). An art therapy intervention for symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 11(2), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2016.1181288

- van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score. Penguin.

- van Westrhenen, N., Fritz, E., Vermeer, A., Boelen, P., & Kleber, R. (2019). Creative arts in psychotherapy for traumatized children in South Africa: An evaluation study. PloS One, 14(2), e0210857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210857

- van Westrhenen, N., & Fritz, E. (2014). Creative arts therapy as treatment for child trauma: An overview. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(5), 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.004

- Vibhakar, V., Allen, L. R., Gee, B., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in children and adolescents after exposure to trauma. Journal of Affective Disorders, 255, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.005

- Visser, M., & Du Plessis, J. (2015). An expressive art group intervention for sexually abused adolescent females. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 27(3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2015.1125356

- Wethington, H. R., Hahn, R. A., Fuqua-Whitley, D. S., Sipe, T. A., Crosby, A. E., Johnson, R. L., Liberman, A. M., Mościcki, E., Price, L. N., Tuma, F. K., Kalra, G., & Chattopadhyay, S. K. (2008). The effectiveness of interventions to reduce psychological harm from traumatic events among children and adolescents: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(3), 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.024

- World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- Yan, H., Chen, J., & Huang, J. (2019). School bullying among left-behind children: the efficacy of art therapy on reducing bullying victimization. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 40. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00040