The global response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has changed daily life in many ways for many people. Yet child development has not paused, and supporting children, families, and care providers of all kinds is as important as ever [Citation1]. – Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University

There has been a lot of media coverage on COVID-19 in children. ‘While the available evidence indicates the direct impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mortality to be very limited [Citation2]’, this editorial is not set to discuss any of this information but instead focuses on the indirect impact of the pandemic on early childhood development (ECD) and child mental health, which has received by far less attention outside of insiders’ circles.

A few points should be made about the importance of addressing the indirect impact of COVID-19 on child development and mental health. First, early childhood (defined here as the period from birth to age eight) is the most critical phase of human development as the foundation for brain development—and therefore our ability to connect with others, function in society, and attain education and social well-being—is built during these critical years [Citation3,Citation4]. This foundation is influenced not only by genes but also by nurturing and responsive relationships with parents and other caregivers [Citation4]. During a pandemic, disease risk, parental job loss, food insecurity, conflicting priorities, and the overall disruption of health and social systems and related services, which all contribute to stress among adults and children, may affect the quality of the interactions young children experience with parents and caregivers, and therefore unsettle the positive environment children need in this important time for brain development.

Second, older children and adolescents are at an increased risk for anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions because of the fear of the unknown and the disruption of daily routines to which COVID-19 contributes [Citation5]. ‘Many of our kids were pretty engaged in their social lives. They were playing sports. They were involved in clubs and activities, or they got to see their friends, at the very least [Citation4]’. This has been limited in the age of COVID-19 and may be experienced as being traumatic by many children and adolescents, therefore contributing to self-isolation [Citation5], and recurring symptoms both in children who were already living with a mental health condition, and others who had not been diagnosed with any mental health illness before the pandemic.

Third and foremost, mental health concerns as related to COVID-19 are of special importance among vulnerable, marginalized and underserved communities and their children. For example, children from immigrant and refugee families are already

at higher risk than other children for depression, anxiety, lack of self-esteem, social isolation, lack of social integration, and undiagnosed mental health disorders. They have limited access to mental health care, and often come from cultures where getting help for mental health problems carries stigma. [Citation6]

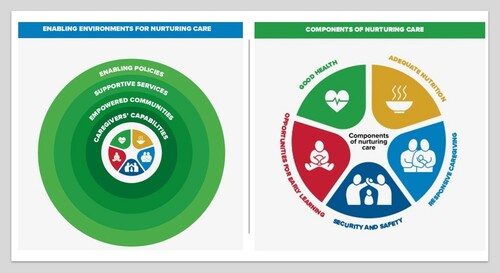

Families alone cannot bear the burden of the response. In early childhood development, the Nurturing Care Framework [Citation9] jointly developed by the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and the World Bank focuses on ‘enabling environments’ and is rightly comprised of enabling policies, supportive services, and empowered communities—all contributing to caregivers’ capabilities to provide children with the kind of care they need and to have a positive impact on the different aspects of child development (See ). Similarly, interventions to improve child and adolescent mental health should be driven by system thinking and affect not only the nuclear family but also the community, built environment, schools, clinical settings, and policies of the countries, cities and neighborhoods where children live [Citation10]. As most disorders have onset in childhood or adolescence, increasing risk for poor outcomes later in life [Citation10,Citation11], making sure we address COVID-19 impact among children should be an easy choice. Engaging with parents, listening to their concerns, and supporting them in these unprecedented times is a strategic imperative. The future of our children, and ultimately our planet, depends upon our ability to prioritize and support families.

Figure 1. The Nurturing Care Framework. Source: World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group. Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018, pages 12 and 17. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

I believe that communication can play a key role in addressing and preventing long-term impact of the child development and mental health crisis COVID-19 is bringing upon us. The examples provided here aim to encourage our authors and readership to start considering ways to get involved in addressing this important issue across research, practice, and policy development.

First, by promoting family-centered care and emphasizing the importance of focusing on family systems and their interactions with other important systems (e.g. healthcare, community, policy, school, workplace), communication interventions and future research can help bring attention to the many barriers to nurturing care that parents and caregivers may face at these unprecedented times and that may contribute to increased stress levels within the family unit.

Communication interventions can also engage with parents and parents groups at local schools, community centers, and pediatric clinics, to assess their needs and provide information, emotional and behavioral support, and culturally-relevant resources to understand and address any changes they may notice in their child or adolescent. For example, some parents may need information on recognizing traumatic reactions in their children, such in response to the disruption caused by COVID-19, which can include a variety of signs (e.g. intense emotional upset, behavioral changes, depression, aggressiveness, changes in sleeping or eating habits, risk behaviors in older children, sudden aches and pains, and others) [Citation12]. In other cases, parents may need support to adapt to a new culture, navigate health and school systems, and/or to re-visit potential feelings of shame in reference to their child’s behavior and traumatic reactions, and be supported in embracing a stigma-free attitude toward mental health issues. Engaging with local community-based organizations and leaders, developing and training local ‘champions’ (e.g. parents who can share their experience with similar issues), and seeking the input and ideas of older children and adolescents in intervention and media design should all be strongly considered to identify cultural beliefs and priorities, and approach resources development with cultural humility within each specific community.

Additionally, professional clinical communication interventions, training modules, and research efforts could all be designed to identify and share best practices in addressing bias and health inequities and improving cultural humility in healthcare settings, so that families from diverse backgrounds and cultures can always trust their local health systems to be ‘non-judgmental' and be inspired by equity, fairness, and transparency in resource allocation, clinical decisions, and other important aspects [Citation13] of their child’s care. Pediatricians and family clinicians could play a key role in initiating conversations on COVID-19 and child mental health, and providing support and resources to parents and caregivers on this topic. Family engagement and psychosocial support are in fact key to identifying and helping children in distress or living with a mental health condition [Citation14], which require long-term commitment from families, clinical teams, schools, communities, and everyone else caring for children during COVID-19 and beyond. This system-thinking approach is not only set to improve provider-parent interactions but also to contribute to the overall quality of care children receive, and to their short-term and long-term outcomes.

Finally, as one last example, advocating for policy change is another key area for communication research and interventions to address the mental health impact of COVID-19 among children. Policy communication and advocacy efforts should consider a bottleneck-removing approach in identifying and addressing social factors and other barriers that may prevent parents and caregivers from effectively contributing to the well-being of their children during COVID-19 and afterward because of actual limitations or increased stress levels posed by them. These may include advocating for expanded access to healthcare services for historically excluded populations (e.g. refugees and immigrants); adequate paid leave and child care benefits so that working parents can continue to ‘put food on the table’ without having to worry about their children’s well-being; increased investment in families from low-income communities, communities of color, and other vulnerable and marginalized groups; priority funding of early childhood and child and adolescent mental health interventions; community centers and recreational programs (whether online or outdoor) by governments and grantmakers; and other issues that may be community- or country-specific. Of course, these are just examples, so we look forward to hearing from our authors and readers on their own professional endeavors and papers on this topic.

I thought to close this editorial with a quote from the 2007 UNICEF Innocenti Report Card [Citation15], which always inspires me, and therefore I often use in my presentations and teaching:

The true measure of a nation’s standing is how well it attends to its children – their health and safety, their material security, their education, socialization, and their sense of being loved, valued and included in the families and societies in which they were born.

This has never been truer as in these unprecedented times.

In this issue

In continuation of our efforts to bring to our readers a variety of topics and perspectives across research and practice, this issue of our Journal includes papers on models of behavioral prediction, health priorities during presidential elections in multiple countries in Europe, and peer advice in the context of diabetes management, among other articles.

I want to highlight our Front Matter section, which is increasingly being used as a space for opinions, commentaries, and perspectives on future directions for health communication and policy advocacy on current issues. In this issue, Front Matter articles focus on multiple topics, from the global COVID-19 pandemic, to the role of social discrimination in perpetuating health and racial inequities, and the importance of patient engagement. Special thanks to editorial board member Dr. Isabel Estrada-Portales from the National Institute of Health in the United States for authoring an insightful and moving piece on Drylongso. Racism, Health Inequity, and a Denial of Pandemic Proportions; to Mark Duman, MRPharmS, also a long-time editorial board member, for co-authoring an article with Prof. Lara Bloom on Engagement Matters as Much as Medicine, a topic our Journal is increasingly exploring; and to Dr. Anne Marie Liebel for her piece about rethinking the role of contact tracers as knowledge makers. Congratulations to all authors and co-authors in this and other sections of this October 2020 issue of the Journal!

Finally, this issue also includes an article collection on Research Insights and Strategies for Professional Clinical Communications, a topic we think is timely given the increasing demands on global health systems, and the need for new professional skills and practices in clinical settings to meet such demands.

We hope the articles in this issue are of interest to your work, research, and professional development. Thank you for your readership and stay well!

References

- Center for the Developing Child, Harvard University. A guide to COVID-19 and early childhood development; 2020. Available from: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/guide/a-guide-to-covid-19-and-early-childhood-development/

- UNICEF. Child Mortality and COVID-19. UNICEF Data, Jul 2020. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/covid-19/

- Conel JL. The postnatal development of the human cerebral cortex. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1959.

- Center for the Developing Child, Harvard University. Experiences build brain architecture; 2020. Available from: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/experiences-build-brain-architecture/

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Learning Network. How COVID-19 is affecting the mental health of children and adolescents. 2020 Jul 15. Available from: https://www.psychcongress.com/multimedia/how-covid-19-affecting-mental-health-children-and-adolescents

- De Milto L. Caring across communities: addressing mental health needs of diverse children and youth. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2015. Available from: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/11/caring-across-communities–.html

- Proctor D. Caring for mental health in communities of color during COVID-19. Culture of Health Blog: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2020 May 5. Available from: https://www.rwjf.org/en/blog/2020/05/caring-for-mental-health-in-communities-of-color-during-covid-19.html.

- UNICEF. COVID-19 and children. UNICEF Data, 2020 Aug. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/covid-19-and-children/.

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, World Bank Group. Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. p. 12 and 17. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Schiavo R. Addressing Child Health Disparities: We Made the Case, We Need A Movement. Presentation at the centers for disease control and prevention division of community health, Office of Health Equity, Health Equity Capacity Institute (HECI), 2015 Oct 27; Atlanta, GA, United States.

- Alegria M, Green JG, McLaughin KA, Loder S. Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U.S. New York (NY): William T. Grant Foundation; 2015; Available from: http://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2015/09/Disparities-in-Child-and-Adolescent-Mental-Health.pdf

- Greenwald R. Child Trauma handbook: a guide for helping trauma exposed children and adolescents. New York (NY): Routledge Mental Health, Taylor & Francis Group; 2005.

- Schiavo R. Addressing health inequities in clinical settings during COVID-19 and Beyond. Presentation at Mount Sinai Kravis Children’s Hospital, Pediatric Grand Rounds; 2020 May 28; New York, NY.

- Thompson RH. The handbook of child life: a guide for pediatric psychosocial care. Springfield (IL): Charles, T. Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2009.

- UNICEF. Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries, Innocenti report card 7. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2007, p. 1. Available from: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc7_eng.pdf